#why is alvar the most boring person on earth

Text

This year’s cemetery month begins with graveyard poetry. For today’s post, I begin with the end: the final stanza of The Jewish Cemetery at Newport by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. The poem was first published 160 years ago, in 1858, and contemplated an abandoned Jewish graveyard established nearly 200 years previously in 1677. Among Longfellow’s contemplation, he wondered about the first major Jewish settlement in the American Colonies and their subsequent disappearance from the streets of Newport Rhode Island a century after their arrival. In similitude, people around the world have wondered about the Jews who lived lived actively within thriving European communities but disappeared by the millions in less than a decade during the Holocaust. Longfellow’s final stanza is this lament:

But ah! what once has been shall be no more!

The groaning earth in travail and in pain

Brings forth its races, but does not restore,

And the dead nations never rise again

Perhaps Hitler and his Nazi sympathizers counted on the fact that the Jews lost in the Holocaust would remain lost and forgotten like the Jews of Newport. But thanks to the efforts of people like Ruth Contreras in Austria, the dead nations are rising again. Perhaps not literally, but they are being revived in the memories of towns across Europe like Pitten, Austria, and their names are being reconnected with family members who have lost contact. Those dead nations are indeed rising, one-by-one.

Four years ago, I posted the photograph of a tombstone in Europe. Like the tombstones of Longfellow’s poem, it was spelled “backward, like a Hebrew book, Till life became a Legend of the Dead.” That tombstone was indeed a mystery to me and my family. We had been unable to find anyone to help us connect that tombstone with or own family legend.

Until ten months ago, that is, when I received an email from Ruth Contreras referring to my blog, and asking about my post, How my Mormon Mom Learned She was a Jew. Attached to Ruth’s message was a photograph of a broken tombstone written in Hebrew lying in the grass. The bottom of the tombstone bore my great-grandmother’s name in Roman lettering. I’d seen that tombstone before, but I didn’t recognize it in its dilapidated condition.

Ruth wanted to know if my grandmother was the same Josephine Daniel who was the daughter of Franziska Abeles Daniel from the tombstone and had lived in Pitten a century ago. If so, could I possibly help her get in touch with any of Josephine’s living relatives? As I read through the letter, I realized that this was a person who had done some in-depth research into my grandmother’s family. She mentioned dates, names, and places particular to my family, and in my intense overload of excitement, I missed the fact that she was even solving the mystery of the tombstone, just like Longfellow’s “mystic volume of the dead.”

The tombstone, finally identified.

My great-grandmother, Franziska “Fanny” Abeles Daniel

My grandmother, Josephine Daniel, and her sister Sommer, at their mother’s tombstone.

I felt like an overexcited puppy being let out to play after a long day at home alone. I was positively bouncing; and if I had a tail, I’m sure my whole back end would have been wagging. The first thing I did was call my parents in Utah to share the message. My mom was just as elated as I was. After all, she had spent years searching for information regarding my third great grandfather who had lived in Pitten all those years ago. This was a break-through for my family. My reply to Ruth’s first inquiry included a photograph of the woman belonging with the tombstone.

Over the next few weeks a flurry of emails went back and forth between Kentucky, Utah, and Austria. Each new message from Austria was followed up by a phone conversation with Mom and Dad. During that first flurry of messages I learned that Ruth was the granddaughter of the family that lived next door to my grandmother and third great-grandfather in Pitten in the years between the first world war and the Holocaust.

My first and most empowering understanding of the Holocaust was my study of The Diary of Anne Frank in eighth grade. To my young mind, Anne’s story explained so much of a grandmother I barely remember. My mother heard grandma speak of her Jewish past only once, and never again. I was able to learn of my own relationship to that Jewish past through a reel-to-reel tape recording of that same conversation. The recording, and my study of Anne Frank raised difficult questions: Who were my relatives in Austria? How many of Grandma’s close friends and cousins died among the six million in the Holocaust? How many others survived? Who were they? Where are they now?

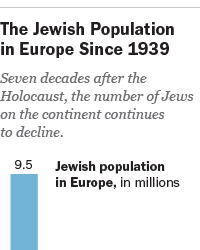

Ruth’s mission, she explained, was to answer some of those questions. She was looking for the members of the former Jewish community in Pitten, Austria, in order to explain what had happened to them after the annexation of Austria to Nazi Germany in 1938. The Jewish community in Pitten was small, but given that out of the 9.5 million Jews living in Europe before 1938, only 1.4 remain, finding the descendants of those missing Jews is like finding a needle in a haystack . Six million died in the Holocaust, and the remaining 2.1 European Jews are scattered across the globe.

In the past ten months, Ruth has been collecting and organizing information, and I have not been telling my stories. I’ve been dealing with life, putting the “grand” into grandmothering, fighting bed bugs (The reason for no posts in September. WHY did we move here?), and feeling guilty for not telling stories. But I have not forgotten that one of the reasons I established this blog was to attract previously unknown family members looking to connect with their ancestors and their untold stories.

My family’s stories are largely unknown, but thanks to Ruth Contreras, I can begin by telling previously unknown stories from my own Jewish ancestors, aunts, uncles and cousins. I hope that Ruth will let me tell her family’s story as well. I’ll never be able to tell even close to six hundred stories of the Jews lost in the Holocaust (let alone six million), but as Ruth reminded me, “The generation of survivors of the Shoah [Holocaust] very often hesitates to speak about what happened, but I think it is the obligation of the second and third generation to find out as much as possible to ensure that this does not happen again.” Ruth is of the second generation. I am of the third. I take this obligation seriously.

Ruth was also able to tell me of some neighbors to my ancestors in Pitten, Austria:

Ruth’s mother and grandparents lived next door to my family before the Anschluss. They relocated to Columbia, and their property was Aryanized. Ruth returned to Austria to reclaim her family’s property, and lives there now.

Johann Jaul and his wife Josephine owned the property my family lived in, and were also victims of the holocaust. The Jauls’ daughter and her husband escaped to Argentina.

A fourth Holocaust victim named Barbara Trimmel.

Related results of Ruth’s efforts include:

A photo of my great-grandmother will be included in an exhibit of Jewish life in the Museum of Contemporary History in Bad Erlach.

A bronze “Stumbling Block” laid in front of the building my third great-aunt lived in before she died in Treblinka.

An article published in Messenger from the Bucklige Welt telling of Ruth’s quest to identify Holocaust victims and their families, including the story of how she found my family through a web search leading her to Stories From the Past.

So the dead nations are rising one by one through the commemoration of their lives in museums, on the streets of their hometowns, magazine articles, and stories told on the internet.

May we never forget.

A special thanks to Pitten Mayor Helmut Berger, Stumbling Block artist Gunter Deming, project initiator Ruth Contreras, and research director Werner Sulzgruber.

The Jewish Cemetery at Newport

BY HENRY WADSWORTH LONGFELLOW

How strange it seems! These Hebrews in their graves,

Close by the street of this fair seaport town,

Silent beside the never-silent waves,

At rest in all this moving up and down!

The trees are white with dust, that o’er their sleep

Wave their broad curtains in the south-wind’s breath,

While underneath these leafy tents they keep

The long, mysterious Exodus of Death.

And these sepulchral stones, so old and brown,

That pave with level flags their burial-place,

Seem like the tablets of the Law, thrown down

And broken by Moses at the mountain’s base.

The very names recorded here are strange,

Of foreign accent, and of different climes;

Alvares and Rivera interchange

With Abraham and Jacob of old times.

“Blessed be God! for he created Death!”

The mourners said, “and Death is rest and peace;”

Then added, in the certainty of faith,

“And giveth Life that nevermore shall cease.”

Closed are the portals of their Synagogue,

No Psalms of David now the silence break,

No Rabbi reads the ancient Decalogue

In the grand dialect the Prophets spake.

And not neglected; for a hand unseen,

Scattering its bounty, like a summer rain,

Still keeps their graves and their remembrance green.

How came they here? What burst of Christian hate,

What persecution, merciless and blind,

Drove o’er the sea — that desert desolate —

These Ishmaels and Hagars of mankind?

They lived in narrow streets and lanes obscure,

Ghetto and Judenstrass, in mirk and mire;

Taught in the school of patience to endure

The life of anguish and the death of fire.

All their lives long, with the unleavened bread

And bitter herbs of exile and its fears,

div>The wasting famine of the heart they fed,

And slaked its thirst with marah of their tears.

Anathema maranatha! was the cry

That rang from town to town, from street to street;

At every gate the accursed Mordecai

Was mocked and jeered, and spurned by Christian feet.

Pride and humiliation hand in hand

Walked with them through the world where’er they went;

Trampled and beaten were they as the sand,

And yet unshaken as the continent.

For in the background figures vague and vast

Of patriarchs and of prophets rose sublime,

And all the great traditions of the Past

They saw reflected in the coming time.

And thus forever with reverted look

The mystic volume of the world they read,

Spelling it backward, like a Hebrew book,

Till life became a Legend of the Dead.

But ah! what once has been shall be no more!

The groaning earth in travail and in pain

Brings forth its races, but does not restore,

And the dead nations never rise again.

Dead Nations Rising One Citizen at a Time This year's cemetery month begins with graveyard poetry. For today's post, I begin with the end: the final stanza of

0 notes