Text

Contemporary Navajo artists pride themselves in blending traditional forms with modern technology, materials and methods. In an age of “decolonization”, artists tell their own stories and their communities’ stories to show there is still much work to do. Paying homage to both their community and other Indigenous identities, artists weave spirituality, activism, and a love of nature as the prevailing themes in Navajo contemporary art.

0 notes

Text

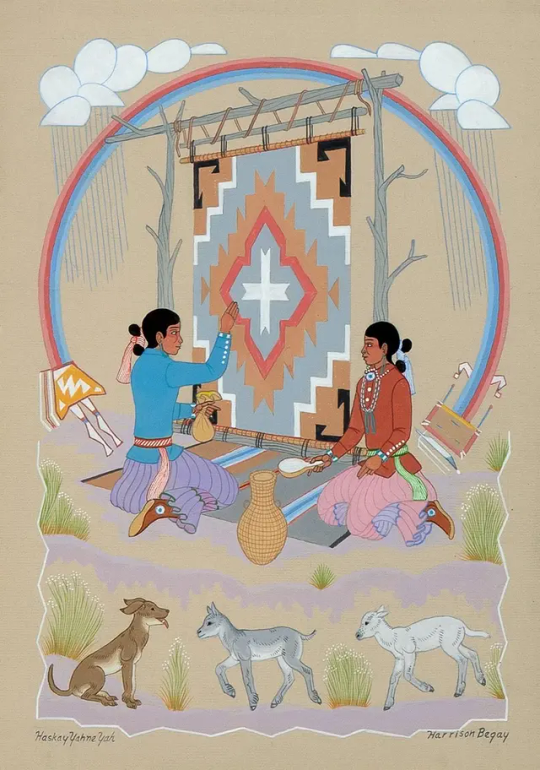

Harrison Begay, Untitled (Two Navajo Girls Weaving). Gouache on paper, 16.5 x 11.5 in. (41.9 x 29.2 cm.)

Harrison Begay also known as Haashké yah Níyá (Warrior Who Walked Up to His Enemy), artist and colleague to the aforementioned Gerald Nailor, created an impressive legacy for himself as one of the best-known contemporary Navajo artists. Begay was also a student of Dorothy Dunn, and in fact the last (at his time of death in 2012) living student of hers at the Santa Fe Indian School. His career spanned over 50 years, working as co-founder of an art-publishing firm, in painting, book illustration and screenprinting.

His work often portrays serene scenes of Navajo daily life in pastel and neutrals, mostly in watercolours and gouache. His subtle tonal work lay flat on the page (as in, little perspectival structures), creating exciting shifts in colour and sensation - the artist was reportedly inspired by Frida Khalo in this way. His works are now held in the collections of The Museum of Modern Art in New York, the Museum of Northern Arizona in Flagstaff, and the Philbrook Museum in Tulsa, and more. As he spent much of his growing up off the reservation, he learned later about traditional Navajo ceremonies from a book by artist Don Perceval, deepening his understanding of Navajo heritage which influenced Begay's work from then on.

SOURCES:

https://www.mutualart.com/Artwork/Untitled--Two-Navajo-Girls-Weaving-/A5DF00B6E68329B5AA1D10117CA0C55D

0 notes

Text

R.C. Gorman, Moon River, lithograph

R.C Gorman was an internationally recognized queer Navajo artist and namesake of the R.C Gorman Navajo Gallery of Sedona in 2016, the fourth of its kind, with the first being in Taos, New Mexico where he lived and worked until his death in 2005. A prolific third-generation artist, he was friends with Andy Warhol and Elizabeth Taylor and became a mainstream artist in his lifetime, yet always prioritized sticking to his roots and representing his culture. Dawn Walker, the Sedona gallery’s manager, told Sedona Monthly that “his work bridge[d] the gap between avant-garde and commercial art.”. He was also dubbed the “Picasso of American Indian Artists” by the New York Times. His lithographs often feature Navajo women admiring, or at least in the midst of, the beautiful Arizona landscape. Recurring backdrops include where he used to tend sheep with his grandmother and aunts, in Canyon de Chelly, where he’d often draw on sand, mud, rocks and sculpted with clay. His grandmother, who he also lived with, encouraged him to become an artist while equipping him with the stories of his artist ancestors and Navajo legends.

His tranquil scenes of Indigenous life sometimes verge on the surreal, creating a mystical, dreamy scene for the viewer to fall into. The role of the woman here honours Indigenous women as earth nurturers. Gorman’s stylistic tendencies borrow from Navajo pottery design and Mexican murals, re-interpreting and re-contextualizing them in these paintings. His work was important in shaping the modern Indigenous artistic aesthetic, and became highly influential for contemporary Indigenous artists today.

SOURCES:

https://sedonamonthly.com/2017/r-c-gorman-navajo-gallery-sedona/

Image source: Photograph by Michael Thompson for Sedona Monthly

0 notes

Text

Gerald Nailor Sr., Untitled (Tourists). Gouache, 14 x 12 3/4 in. (35.6 x 32.4 cm).

Bequest of Dorothy Dunn, 1992. Museum of Indian Arts and Culture/Laboratory of Anthropology.

Contemporary Navajo artists like Gerald Nailor Sr. aim to create art that honours their ancestry and tackles modern issues, using a blend of new methods and materials and traditional ideas or techniques. Nailor, born in Pinedale, New Mexico and was given the Diné name Toh Yah (Walking By the River). In 1937 he studied under Dorothy Dunn at the Sante Fe Indian School. Nailor was known for his silkscreen prints and the art-publishing firm he established with his friend and artist Harrison Begay, called “Tewa Enterprises” that specialized in Indigenous art and silkscreen printing.

In this piece, the artist is showing the issues of exoticism prevalent in Western consumption of Indigenous arts and thought. In early Navajo rugs and blankets, red was used sparingly as it was hard to obtain but special blankets like Chief’s blankets had large swaths of red in its compositions, until the influx of synthetic dye production. The blanket in this image revives the traditional Navajo Spider Woman (Na'ashjé'íí Asdzáá) design that was used in blankets, rugs, and baskets. This cross design was given to early weavers, mostly before the 1900s, to remember her teachings and wisdom. The Spider Woman is seen as a Grandmother to the community, a being that constantly protects and aids humanity; she brings balance and harmony to the world, and is said to punish the misbehaving.

The family on the left seem to be admiring and connecting with the artwork, the mother perhaps reminiscing or remembering, as the couple on the right seem to show conflicting emotions; the wife looks interested, but the husband looks repulsed, trying to pull her away.

SOURCES:

“New Mexico Art Tells Its History.” New Mexico Tells New Mexico History - Nailor, New Mexico Museum of Art , online.nmartmuseum.org/nmhistory/art/nailor-untitled-tourists.html.

0 notes

Text

Doll: baby in typical carrying frame; Doll of Navajo woman, fabric body & clothes, wool hair, bead & metal jewelry. Fabric; Wood; Wool; Glass bead; Metal; Leather. 11.7 cm x 4.1 cm x 4.1 cm; 20.3 cm x 8.1 cm x 4.3 cm

This image shows two handmade dolls, featuring a Navajo woman and a baby in the typical carrying frame. Both dolls have hair made of wool and are wearing beaded and metal jewelry. Though the work is undated, one can assume it was made during the mid-1800s from the woman’s dress and the doll’s stylistic traits. Dolls in this era were usually made to be sold to tourists, or sometimes for personal use as a way to maintain cultural heritage and show the daily life of a Navajo community member. Some of these dolls were also used as fashion inspiration for Navajo women, much like how the European fashion dolls of the 16th century were used to advertise pieces by designers for clients overseas without having to paint it (like a prototype of sorts). Navajo women and European women influenced each other’s styles in this era; European wives would go back to their homes with Navajo style clothing and vice versa sometimes. For example, some Navajo women were inspired by the maximalist use of satin in Europe and incorporated it into their dress (or substituting it with velvet), personalizing it with silver and coin buttons. The moccasins, leg wraps, floral skirt, and wide belt are also typical of Navajo dress in this time.

Though some Navajo dolls were meant to be sacred or instructional (and the excavation of them deeply upset local communities for possibly inflicting harm on themselves), these dolls seem to be more recreational, meant to be played with or collected, as they are not decorated like kachina dolls, which would have a more instructive role in teaching children the nation’s mythology. Additionally, the presence of the baby doll lends itself to the idea that this work was more showing cultural and daily life, and was meant to be collected/shared rather than revered.

SOURCES:

Spain, James N. “Navajo Culture and Anasazi Archaeology: A Case Study in Cultural Resource Management.” Kiva, vol. 47, no. 4, 1982, pp. 273–78. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/30247346.

0 notes

Text

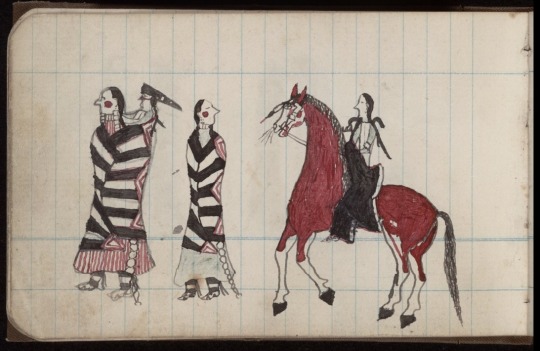

Roan Eagle drawing of two women wearing Navajo blankets, one with a baby on her back, and man on horseback, 10 x 16 cm, 1880. Ledger drawing.

This colourful piece, done on lined paper, is an example of ledger art. Ledger drawings are narrative pieces, usually drawn but sometimes painted on paper or cloth, that was a popular art form in the Plains, as well as from the Plateau and Great Basin. It first rose to prominence during the 1860s to the 1920s, then saw a revival in the 60s and 70s. Originally, the tradition began as a way for Indigenous communities to control their own narratives, and to document their experiences with settlers without settlers trying to rewrite histories. Ledger art gained its name because it was first made on the paper of ledger books that the settlers brought, sometimes painting over the inventory and text it had before. Historically, this was simultaneously a large but subtle shift, as most Indigenous communities passed down stories and histories orally - this was a way to depict these stories pictorially, another common storytelling device, without having to shift to a completely new practice, like an extensive written form. This was a natural succession from petroglyphs, then pictographs, then painting on hides (buffalo specifically), tipis, and clothing.

Over time, the pictures in these ledger pages shifted from scenes of war, forced migration and courtship to scenes of reservation life and assimilation into American life under oppression. A demand for Indigenous ledger art came about in the late 1870s when Plains prisoners at Ft. Marion (Florida) were encouraged to sell them at $2 a piece. The 1880s saw a rise in ledger drawings made specifically for sale (and at times at the request of anthropologists), sometimes reminiscing on ceremonial life and culture before the settlers.

The image above seems to be a scene depicting the forced migration of the Navajo community, showing two Navajo women with a baby, with one looking back at the man on the horse (presumably an officer/settler). The bold colours are striking against the aged, lined paper, and express a melancholic ferocity in the medium's strokes across the page.

SOURCES:

“The Ledger Art Collection.” Milwaukee Public Museum, www.mpm.edu/research-collections/anthropology/online-collections-research/ledger-art-collection.

Image source: https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.12135786

0 notes

Text

Navajo Bird Necklace, ca. 1890, silver, turquoise, and hide. Portland Art Museum, The Elizabeth Cole Butler Collection.

The use of turquoise in Navajo jewelry was an extremely popular technique, both because of its abundance and cultural significance but also because it was preferred in tourist sales during colonization. It is the first of the Navajo four sacred stones (the others being white shell, yellow abalone, and jet black), following the cardinal colours of the sacred mountains. It is believed to bring good health and provide protection for the owner, and is often given to babies at birth in the form of beads. It is also used in puberty rites, marriage, initiation ceremonies, and healing ceremonies. Similarly, the Pueblo hold the stone sacred, including it in their regalia in the growing season to encourage rain.

As previously mentioned, the Navajo place importance on birds, which is featured in this piece as a beautiful pendant.The ring shapes along the sides of the necklace resemble talons, adding to the bird imagery, possibly as a symbol to ward off negative energies or harm to the wearer. The beads are weaved through with hide (animal unknown), making it sturdy but also providing that connection to nature prevalent in Navajo works.

The stone is known to change colour overtime, as it is a soft stone, becoming a darker, mossy green. Navajo belief is similar to other parts of the world; some think it is a sign of the stone absorbing and deflecting negative energy or poison, while others see it as a reflection of the wearer’s health. Due to all these reasons, and because of its beauty, turquoise jewelry was wildly popular among tourists and settlers; the women of the community made and sold them to support their tribe and it thus became one of the most popular forms of art known of the Navajo Nation on an international level.

SOURCES:

McBrinn, Maxine. “Turquoise, Water, Sky: The Stone and Its Meaning.” Museum of Indian Arts & Culture, Curator of Archaeology, MIAC, www.indianartsandculture.org/whatsnew/&releaseID=292#:~:text=The%20Navajo%20link%20turquoise%20to,healing%20ceremonies%20and%20other%20rituals.

Image source: https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.11743528

0 notes

Text

Sikyatki polychrome pottery bowl. Navajo/Pueblo, A.D. 1250-1540, 9.5 cm x 24 cm. Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University.

This piece was found in the Sikyatki archaeological site, former Hopi village and present day Navajo County in Arizona. The work shows the intermingling history of Hopi, Pueblo and Navajo communities. The polychrome piece features a bird interior - it was common for the bowls of this era to have a plain outer shell with a highly decorated, stylized center. In Sikyatki and early Navajo artwork, as well as modern ones, the bird and its wide feathers symbolizes a variety of things such as wisdom, truth, honor, freedom and strength, as well as the powerful connection between the owner and the Creator. Many Sikyatki food basins had birds with different designs or shapes on the tips of their feathers, marked with different colours (usually in colour palettes of three or less). It is thought that the different designs represent natural phenomena, like rays of the sun or droplets of rain.

According to J. Walter Fewkes, the presence of different types of feathers and its designs is representative of gift-giving and ceremonial traditions. For example, the feathers directly under the breast of the bird or right underneath the wing is supposed to be especially significant in its role in ceremony, though its reason for that is not known to Western researchers and presumably not freely given outside the sanctity of a ceremony. In the image above, we see four feathers which are speculated to represent the sun - it was also believed that the Holy People traveled down in sun rays and lightning bolts, giving the use of layered symbolism even more significance. In Mayan and Aztec symbolism, the three- and four-feathered figure held great importance as well.

The bowl is an example of how the aesthetic and the spiritual were constantly intertwined in early Navajo art; though the ceramic could have been merely a household item purely for function, the emphasis on the four-feathered bird symbol (and with how much care is taken to paint it) reminds the viewer that it likely had a higher ceremonial use as well.

SOURCES:

FEWKES, J. WALTER. “The Feather Symbol in Ancient Hopi Designs.” American Anthropologist, vol. A11, no. 1, Jan. 1898, pp. 1–14, https://doi.org/10.1525/aa.1898.11.1.02a00010.

Image source: https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.15561007

0 notes

Text

Bowl, undated artifact. Artist unknown. Davis Museum at Wellesley College, Wellesley, MA.

This ceramic bowl is decorated with a Navajo ‘House Pattern’ design, gifted from Mary Chamberlain to the Davis Museum at Wellesley College, measured at 4 5/16 in. x 6 11/16 in. (10.9 cm x 17 cm). The geometric design shares common traits with other Navajo designs decorating the home (ex. In rugs or other textiles), with the triangular shapes, diamond shapes, linear motifs and scattering of rounded edges. Symbolic meaning is embedded within these geometric designs, like how many triangles represent the mountains of the natural world. In Navajo culture, geographical boundaries were not set in stone through governments but loosely defined and contained within the two sacred mountains, Gobernador Knob and Huerfano Mesa, a region referred to as the Dinétah.

Mountain imagery can also represent the Four Sacred Mountains (the four directions). These are the four mountains along the boundaries of the Navajo Nation, where each is assigned a colour and direction, and is seen as a deity essential to Navajo survival. They are named in sunwise order: Sisnaajiní or Blanca Peak (blue, east), Tsoodził or Mt. Taylor (yellow, south), Doko'oosłííd or the San Francisco Peaks (black, west), and Dibéntsaa or Hesperus Peak (white, north). Lines are often symbols for rain. This bowl shows some Pueblo inspiration (the general shapes, line variety and line placement), but lacks the black-on-black technique Pueblo people use, making it a mix of Navajo and Pueblo imagery.

Home ceramics were often made by the women of the household, depicting spiritual journeys, ceremonial practices, creation tales, family lineage, mythology, tribe history and more. Many of these ceramics are imbued with reverence for the natural world.

SOURCES:

Jett, Stephen (1992). "An Introduction to Navajo Sacred Places". Journal of Cultural Geography. 13 (1): 29–39.

Pierce, Trudy (1992). Sky Is My Father (1 ed.). University of New Mexico Press. pp. 69–75, 90–96.

0 notes

Text

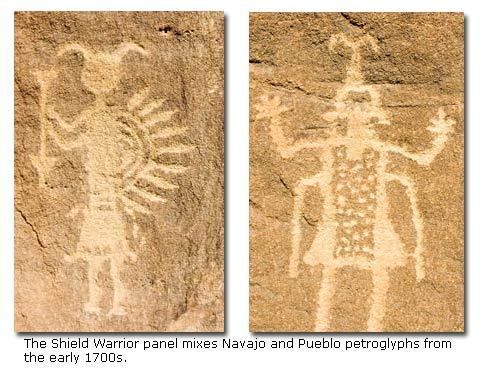

The Shield Warrior panels, Navajo/Pueblo petroglyphs, recorded in the early 1700s. Artist unknown.

This first work is an example of pre-contact art that was created in both Navajo and Pueblo tradition and aesthetics, showing the relationship that the tribes shared at that time. The panels feature a common motif seen in early Navajo rock art (petroglyphs), which is the shield-bearing warrior. This symbol is one of the most studied icons and may be the one of the first recorded rock art images in the southwest United States, and in most cases were made prior to the advent of the horse. One of the unique parts of Navajo representations of warriors and shields are that the shields often look like they are fused to the body, as the figures lean more anthropomorphic rather than wholly human. It is thought to derive from Mexican symbolism, traveling from Pueblo iconography to the Navajo Nation. The symbol seems to wane from both tribe’s iconography, however, after the arrival of the Spanish and the rise of horse warfare - but does not disappear completely in Navajo tradition, the symbol even seeping into the 19th century.

According to Hugh C. Rogers, the disc-shape may not have always represented a literal or physical shield, but sometimes captures the essence of a celestial body, such as the moon or sun. Though these panels display lone warriors with their shields and weapons, some shield-bearing warrior panels show them in full scenes with game animals, equestrians, and sometimes Navajo Holy People. As the shields can represent celestial bodies, so can what is inside and surrounding the shield; dotted marks can be stars, lines reflecting inside and out are thought to represent the gleam of light bouncing off the material from the sun, displaying geophysical or celestial phenomena that translates into metaphysical concepts. Head shapes of the figure differentiate various identified or unidentified Holy People, often found in ceremonial iconography; limbs are usually static but sometimes (like the image on the left) the feet are turned sideways, probably to convey movement.

The iconography of the shield-bearing warrior and its symbolism in totality can only be assumed, especially since its popularity seemed to live a shorter life than other cultural symbols, as well as living on solely through petroglyphs (with the exception of one recovered painting). What researchers do know is it was created either during or for war ceremonies, with an accompanying ritual - the details of which have been lost to the suppression of Indigenous traditions by colonial forces.

SOURCES:

Rogers, Hugh C. “The Shield Bearing Warrior in Navajo Era Rock Art.” Kiva, vol. 68, no. 3, 2003, pp. 247–69. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/30246708.

Image from: https://www.desertusa.com/desert-activity/navajo-rock-art.html

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Navajo people were originally part of a group called the Athapaskans that lived in western Canada, speaking the Na-Dené Southern Athabaskan language. The group called themselves Diné, meaning ‘people’, and migrated south as a nomadic tribe after 1300, eventually settling in the American southwest in 1400. By then, they had crossed paths with the Pueblo, sharing and mixing cultural elements like art techniques, farming skills and more. The most common food grown was corn, squash, and beans, alternatively referred to as the Three Sisters. Today, the Navajo Nation is the biggest federally recognized tribe in the United States, with the largest reservation in the country. Its region covers the land of Arizona, Utah, and New Mexico with over 399,494 enrolled tribal members.

After the Spanish colonized the areas, Navajo communities learned other things like horse riding and tending to cattle. The artwork of the community thrived despite the unrest of colonization, honing their skills in weaving, basketry, doll-making, textiles, and more (for both trade and tourism to support their communities, and to maintain cultural traditions in the face of oppression). Other popular forms of art practices include jewelry making, sand painting, silversmithing, and pottery.

SOURCES:

Saville-Troike, Muriel. “Navajo Art and Education.” Journal of Aesthetic Education, vol. 18, no. 2, 1984, pp. 41–50. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/3332498.

"Aboriginal Population Profile, 2016 Census". www12.statcan.gc.ca/. Statistics Canada. 21 June 2018. Archived from the original on 30 January 2022. Retrieved 31 December 2021.

Watkins, Thayer. "Discovery of the Athabascan Origin of the Apache and Navajo Language" Archived 2014-11-12 at the Wayback Machine, San Jose State University (retrieved: 28 November 2010).

1 note

·

View note