Photo

August 31, 2012 coronal mass ejection, observed by NASA's Solar Dynamics Observatory (SDO).

NASA Goddard:

On August 31, 2012 a long filament of solar material that had been hovering in the sun's atmosphere, the corona, erupted out into space at 4:36 p.m. EDT. The coronal mass ejection, or CME, traveled away from the sun at over 900 miles per second.

#NASA#Solar Dynamics Observatory#SDO#coronal mass ejection#sun#corona#space#astronomy#astrophotography#Center for Creative Photography#CCP#Astronomical#Beyond

498 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Genna Duberstein, lead multimedia producer for heliophysics at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center, gives a TEDx talk about Solarium, an immersive video project created using data from NASA's Solar Dynamics Observatory.

Solarium is currently on view in the Our Solar System gallery. For more information, visit nasa.gov/solarium.

#NASA#solar dynamics observatory#SDO#Solarium#Genna Duberstein#TEDx#center for creative photography#Astronomical#Beyond

1 note

·

View note

Photo

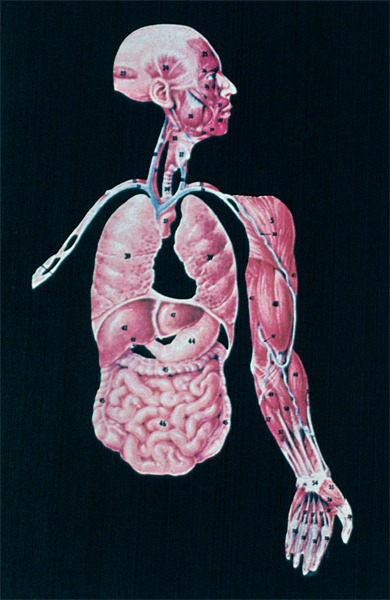

Various images from the Voyager Golden Record project.

The Voyager Golden Record, copies of which flew aboard Voyager 1 and Voyager 2, twin unmanned space probes launched in 1977, was an interstellar message in a bottle. The project was curated by a team of scientists, artists, and thinkers that included Carl Sagan of Cosmos fame, author Ann Druyan, and science writer Timothy Ferris. The identical gold-plated phonograph records contain more than a hundred analogue-encoded images meant to illustrate life on Earth, ambient recordings of sounds familiar to Earth’s inhabitants, and music by artists from Beethoven to Blind Willie Johnson. Their covers are engraved with images intended to tell intelligent beings who come upon them who we are and how to reach us.

#NASA#voyager#Golden Record#Carl Sagan#astronomy#photography#Center for Creative Photography#CCP#Astronomical#Beyond

19 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Clockwise from top left: Thor's Helmet, Gallery M88, Star Cluster M13, the Eagle Nebula. Images courtesy Adam Block.

Photographs by CCP guest speaker Adam Block, manager and primary speaker of the UA Science Mt. Lemmon SkyCenter and monthly contributor to Astronomy magazine. To view more of Adam's images and purchase prints, visit adamblockphotos.com. To learn about the SkyCenter's programs, visit skycenter.arizona.edu.

#Adam Block#University of Arizona#UA#Mt. Lemmon SkyCenter#astrophotography#astronomy#photography#Center for Creative Photography#CCP#Astronomical#Beyond

57 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

April 23rd, 2015 lecture at the Center for Creative Photography, hosted in conjunction with “Astronomical: Photographs of Our Solar System and Beyond.” Adam Block is a leading astrophotographer and the founder of the UA Science Mt. Lemmon SkyCenter stargazing programs; his work appears frequently on NASA’s “Astronomy Picture of the Day” website and he writes a monthly column on astrophotography for Astronomy magazine. Adam speaks about how modern images of the cosmos are made, how they influence the field of photography, and just what makes them so compelling.

#Adam Block#University of Arizona#UA#Mt. Lemmon SkyCenter#astrophotography#photography#telescope#Ansel Adams#NASA Voyager#Hubble Space Telescope#Center for Creative Photography#CCP#Astronomical#Beyond

0 notes

Video

youtube

April 23rd, 2015 lecture at the Center for Creative Photography, hosted in conjunction with “Astronomical: Photographs of Our Solar System and Beyond.” Adam Block is a leading astrophotographer and the founder of the UA Science Mt. Lemmon SkyCenter stargazing programs; his work appears frequently on NASA’s “Astronomy Picture of the Day” website and he writes a monthly column on astrophotography for Astronomy magazine. Adam speaks about how modern images of the cosmos are made, how they influence the field of photography, and just what makes them so compelling.

#Adam Block#University of Arizona#UA#Mt. Lemmon SkyCenter#astrophotography#photography#telescope#Ansel Adams#NASA Voyager#Hubble Space Telescope#Center for Creative Photography#CCP#Astronomical#Beyond

0 notes

Photo

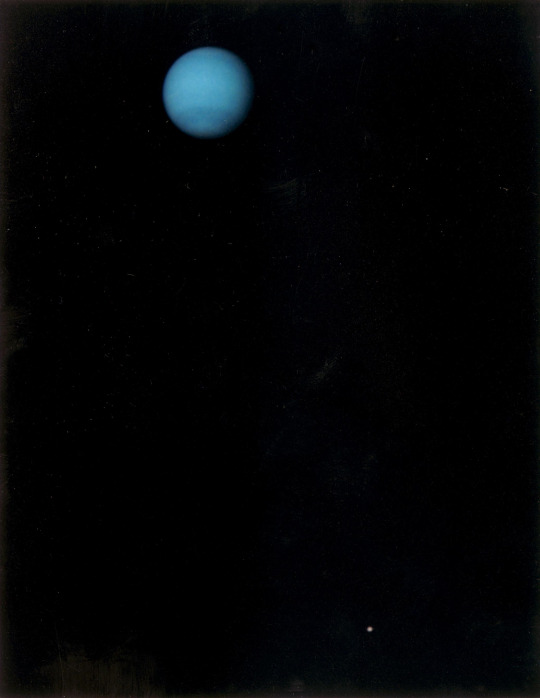

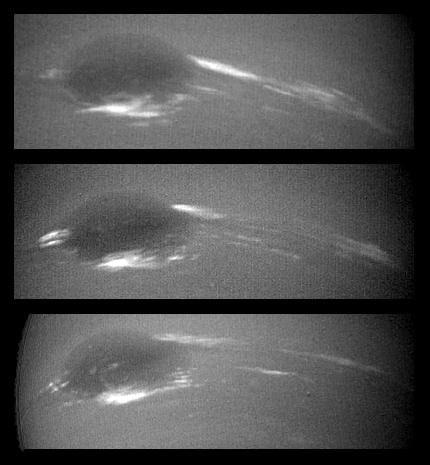

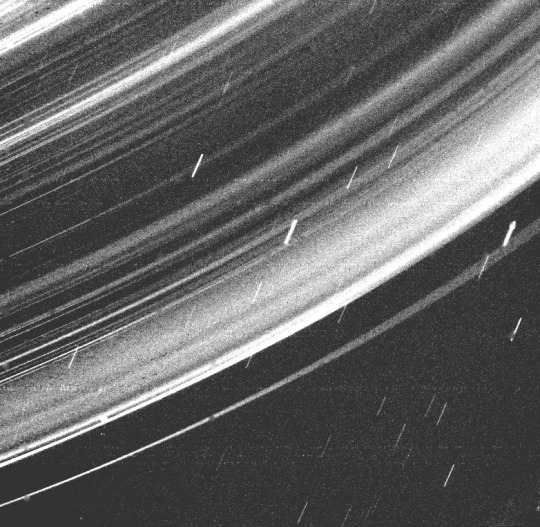

NASA/JPL-Caltech/Voyager 2

Various views of Neptune, 1989

Gelatin silver and chromogenic prints

Images courtesy NASA/JPL-Caltech

The top right photograph shows Neptune’s ring system. Each half of the image represents a single 591-second exposure, taken with a clear filter. Neptune’s rings were too faint to register if Neptune itself were in view, evidenced by the overexposure at the inner edge of both halves of the image due to the planet’s much greater brightness.

In the middle image, the evolution of Neptune’s weather is visible over a period of thirty-six hours, spanning two revolutions of the planet. This series of three photographs, each taken eighteen hours apart, documents changes in the clouds of frozen methane surrounding Neptune’s Great Dark Spot (a storm system with roughly the diameter of Earth).

Voyager 2 is the only spacecraft to encounter Uranus and Neptune up-close. It discovered ten previously unknown satellites of Uranus and six of Neptune. The views captured nearly three decades ago by Voyager 2 remain the best images of both outer planets.

The prints on view in the Our Solar System gallery are on loan from the University of Arizona Space Imagery Center. A partial selection of those images is recreated here using digital scans of a different set of Voyager 2 prints made by the California Institute of Technology Jet Propulsion Laboratory in cooperation with NASA. To view thousands more photographs from NASA’s Planetary Image Archive, visit photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov.

#NASA#JPL#Caltech#Voyager 2#Neptune#chromogenic print#gelatin silver print#twentieth century#20th century#Center for Creative Photography#Astronomical#Our Solar System

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

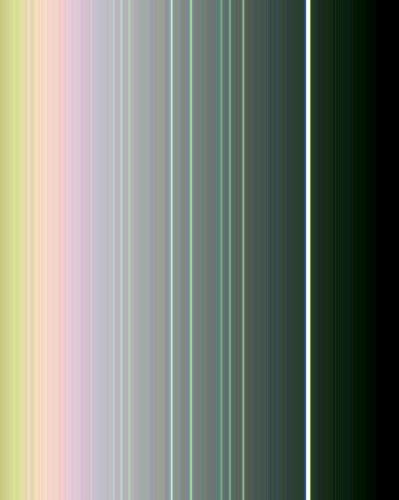

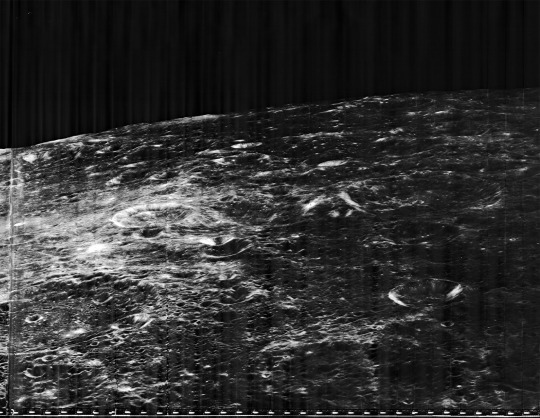

NASA/JPL-Caltech/Voyager 2

Various views of Uranus, 1986

Gelatin silver and chromogenic prints

Images courtesy NASA/JPL-Caltech

The bottom image presents two views of Uranus’s pole of rotation, one a true color image constructed from blue-, green-, and orange-filtered photographs; and the other a false color image that exaggerates the atmospheric variations at the pole. In the view on the right, ultraviolet-, violet-, and orange-filtered data were coded, respectively, as blue, green, and red. The view reveals a dark haze or “hood” over the pole, which gives way to progressively lighter convective bands moving toward the equator. The contrast between the bands shown here is computer-enhanced, making subtle variations in Uranus’s atmospheric composition appear stark.

The top left view depicts all nine of Uranus’s known rings in false color. The brightest and furthest ring from Uranus is at right in this photograph. Color averages were taken from two sets of images made with green, clear, and violet filters in order to determine the correct color relationships between each ring. The bright lines are the rings, while the fainter pastel bands are relics of computer enhancement.

The prints on view in the Our Solar System gallery are on loan from the University of Arizona Space Imagery Center. A partial selection of those images is recreated here using digital scans of a different set of Voyager 2 prints made by the California Institute of Technology Jet Propulsion Laboratory in cooperation with NASA. To view thousands more photographs from NASA’s Planetary Image Archive, visit photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov.

#NASA#JPL#Voyager 2#Uranus#rings#chromogenic print#gelatin silver print#twentieth century#20th century#Center for Creative Photography#Astronomical#Our Solar System

0 notes

Photo

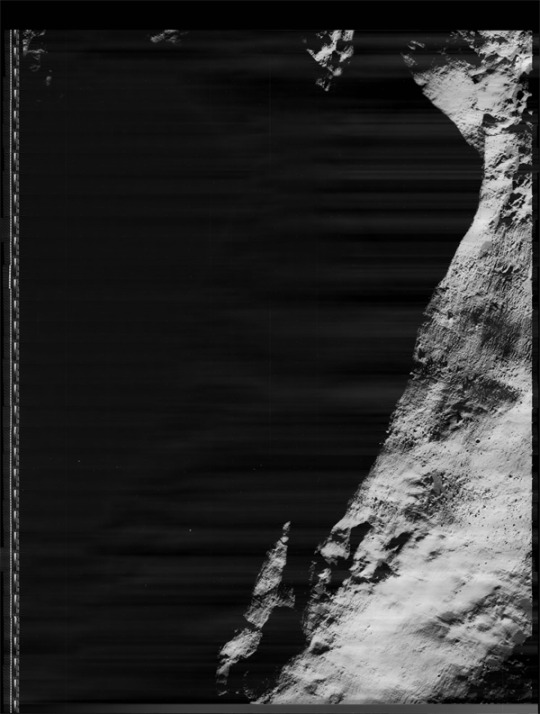

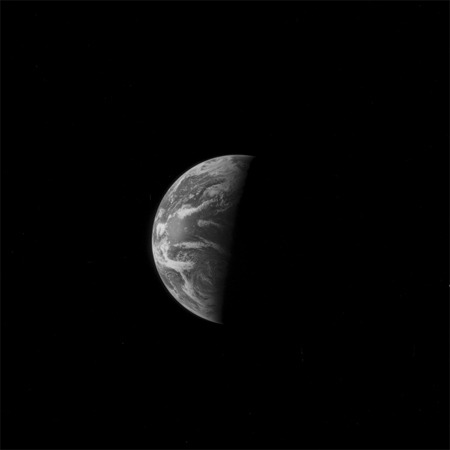

NASA/Lunar Orbiter 1

I-102 H2 and I-102 H3, 1966

Gelatin silver prints

Images courtesy NASA/Lunar and Planetary Institute

These image from Lunar Orbiter 1 are two of the first ever “Earthrise” photographs. The unplanned, over-the-shoulder view was initiated by Dale Shellhorn, a University of Arizona-trained astrophysicist. It shows the arc of the setting Sun, called the “terminator,” which spans from Antarctica on the left-hand side in this image, to Britain on the right. While it was not the first image of our planet seen from space, this photograph, with the Earth dwarfed by a profoundly alien landscape, captivated the public upon its release. Reactions to it echoed those of several Apollo astronauts who reported pangs of overwhelming homesickness when seeing their distant planet from the Moon.

The print of I-102 H2 on view in the To the Moon gallery is on loan from the University of Arizona Space Imagery Center. The image shown here, along with I-102 H3, which is not on view, was digitally scanned from a different set of Lunar Orbiter prints by the Lunar and Planetary Institute in cooperation with NASA. To see the complete archive of digitized photographs from all five successful Lunar Orbiter missions, visit lpi.usra.edu/resources/lunarorbiter.

#NASA#Lunar and Planetary Institute#Lunar Orbiter 1#Earthrise#moon#gelatin silver print#twentieth century#20th century#Center for Creative Photography#Astronomical#To the Moon

4 notes

·

View notes

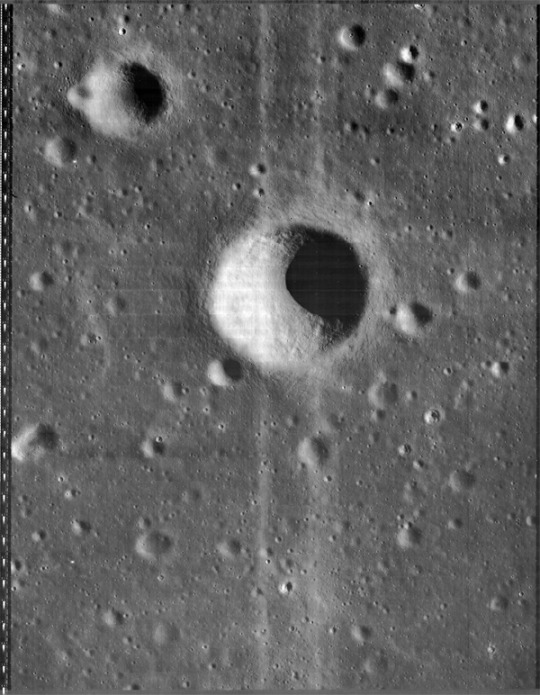

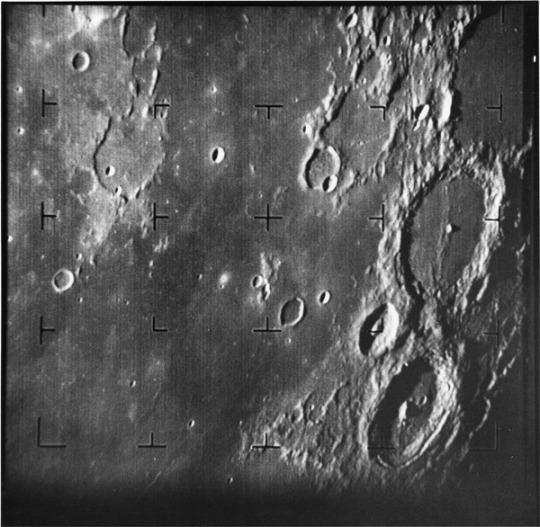

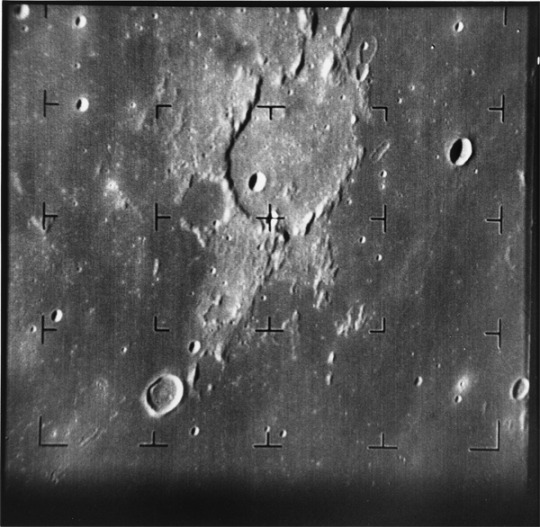

Photo

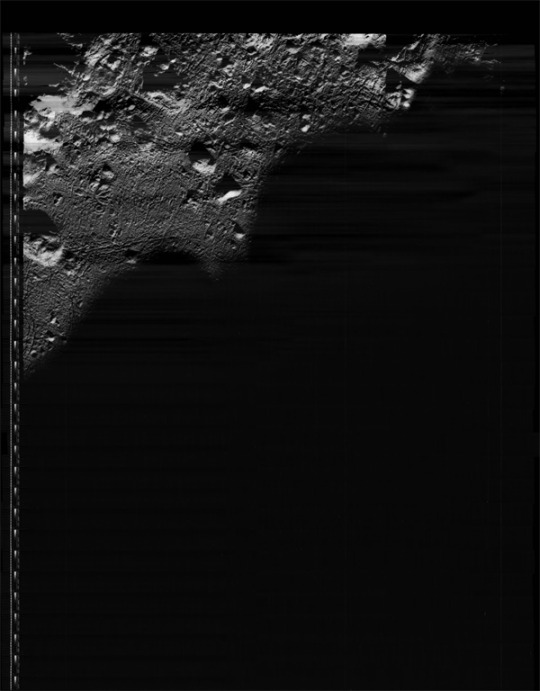

NASA/Lunar Orbiter I-V

Various photographs, 1966-67

Gelatin silver prints

Images courtesy NASA/Lunar and Planetary Institute

The Lunar Orbiter program was initiated to scout potential landing sites for manned flights to the Moon. Five unmanned Lunar Orbiter flights collectively imaged 99 percent of the lunar surface at a resolution of two hundred feet or better. The Lunar Orbiter spacecraft carried a camera system unlike any other in the history of the U.S. space program: it comprised two film cameras, one high- and one moderate-resolution, which used conventional gelatin-based negatives. Exposed negatives were automatically developed onboard, and then scanned and relayed by radio to Earth. Many Lunar Orbiter pictures, including some here, contain bubbles or other flaws resulting from uneven chemical processing.

Lunar Orbiter images were used in conjunction with those from Surveyor. By cross-referencing ground-level and aerial views of the lunar topography, scientists could determine distances and elevations with accuracy. A group of photographs made by Lunar Orbiter 3 allowed UA astronomer Ewen Whitaker to pinpoint the landing site of the unmanned Surveyor 3 in an ancient lava field. The area was so ideal that the Apollo 12 lunar module, the second manned spacecraft sent to the Moon, touched down less than two hundred yards from the deactivated Surveyor 3, allowing its crew the proximity to make portraits of their robotic forerunner.

The prints on view in the To the Moon gallery are on loan from the University of Arizona Space Imagery Center. A partial selection of those images is recreated here using digital scans of a different set of Lunar Orbiter prints made by the Lunar and Planetary Institute in cooperation with NASA. To see the complete archive of digitized photographs from all five successful Lunar Orbiter missions, visit lpi.usra.edu/resources/lunarorbiter.

#NASA#Lunar Orbiter#moon#gelatin silver print#twentieth century#20th century#Center for Creative Photography#Astronomical#To the Moon

6 notes

·

View notes

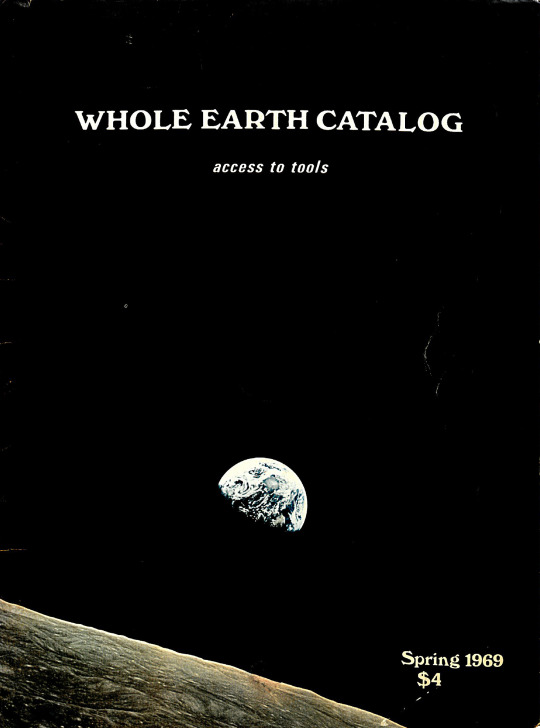

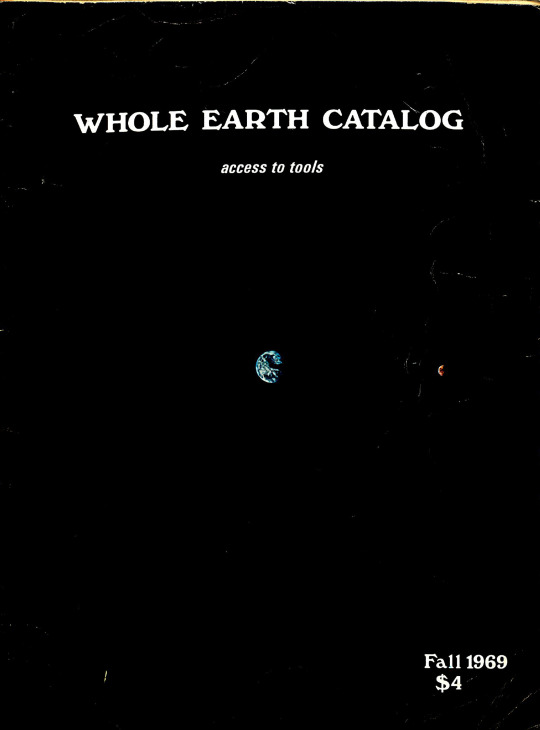

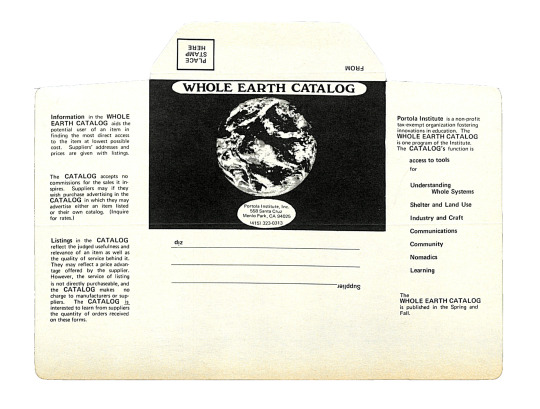

Photo

Covers, pages, and order form from the Fall 1969 and Spring 1969 issues of the Whole Earth Catalog.

The Whole Earth Catalog was, in its own words, like “Sears Roebuck or Consumer Reports, merely attuned to a new market, the sub-economy of dope and rock.” In truth, it was much more. The brainchild of video artist Stewart Brand, the Catalog was a distribution mechanism for tools and literature that promoted sustainable living. It espoused radical visions of architecture and design, media and communications theory, and community practices, from luminaries like Buckminster Fuller, Marshall McLuhan, and Wendell Berry. From its first issue in 1968 to its final one in 1971, the Catalog operated as a community in print that connected dispersed countercultural groups, from scientists to survivalists. Steve Jobs once called it “Google in paperback form.”

Prior to the publication of the first Whole Earth Catalog in 1968, Stewart Brand was involved in a campaign for public access to images from NASA space missions. He distributed buttons that read, “Why haven’t we seen a photograph of the whole Earth yet?” The photographs, he reasoned, would have universal impact—they would create a sense of global identity and common purpose. NASA’s decision to release their images into the public domain coincided with the Catalog’s release, and each biannual issue featured a cover image of the Earth seen from space.

#Whole Earth Catalog#Stewart Brand#Portola Institute#twentieth century#20th century#Center for Creative Photography#Astronomical#Beyond

12 notes

·

View notes

Photo

July 28, 1964: Ranger 7 Camera "A" footage of the unmanned spacecraft's final moments before its impact into the Mare Cognitum region of the Moon.

9 notes

·

View notes

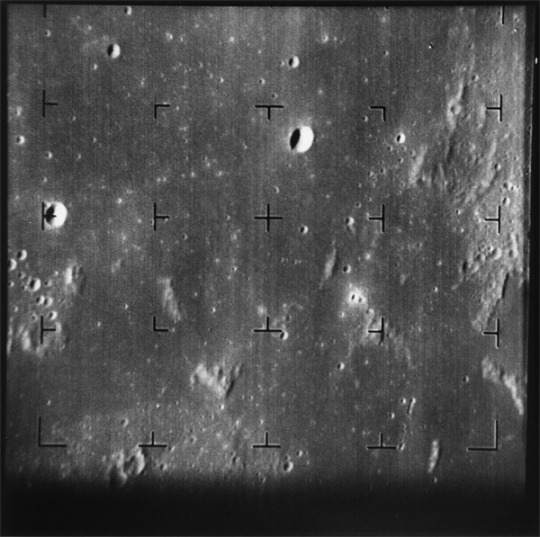

Photo

NASA/Ranger 7

Camera "B" photographs 1, 40, 80, 120, 160, and 200, 1964

Gelatin silver prints

Images courtesy NASA/Lunar and Planetary Institute

The Ranger program was NASA’s first attempt to send spacecraft to the Moon. Unmanned Ranger craft were intended to crash-land onto the lunar surface, transmitting images up until impact. On July 31, 1964, after six failed Ranger flights, NASA’s Ranger 7 successfully relayed over four thousand images of the Moon back to Earth. The craft crash-landed into an area of smooth volcanic rock on the Moon’s near side, later dubbed Mare Cognitum (Known Sea) in honor of the mission. The last few photographs from Ranger 7, taken seconds before the spacecraft hurtled to its demise, had a resolution nearly one thousand times greater than any that had been achieved with Earth-based telescopes.

Returning high-resolution images was one of the main objectives of the Ranger program. Rangers 6 through 9 were equipped with a bank of six television cameras with varying focal lengths to provide both wide- and narrow-angle views. The cameras exposed images in the form of electrical impulses onto photo-sensitive metal plates, which were then scanned, converted to radio signals, and transmitted to Earth. Once the images reached Ranger Mission Control at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, they were recorded onto film. The images returned by Ranger 7 gave NASA scientists their first confirmation that there were lunar areas that could be used as sites for manned landings. Rangers 8 and 9 would take some twelve thousand more pictures, offering unprecedented insight into the composition of the Moon’s surface.

The prints on view in the To the Moon gallery are on loan from the University of Arizona Space Imagery Center. The selection of images is recreated here using digital scans of a different set of Ranger 7 Camera "B" prints made by the Lunar and Planetary Institute in cooperation with NASA. To see the complete archive of digitized photographs from all three successful Ranger missions, visit lpi.usra.edu/resources/ranger.

#NASA#Lunar and Planetary Institute#Ranger 7#moon#Mare Cognitum#gelatin silver print#twentieth century#20th century#Center for Creative Photography#Astronomical#To the Moon

0 notes

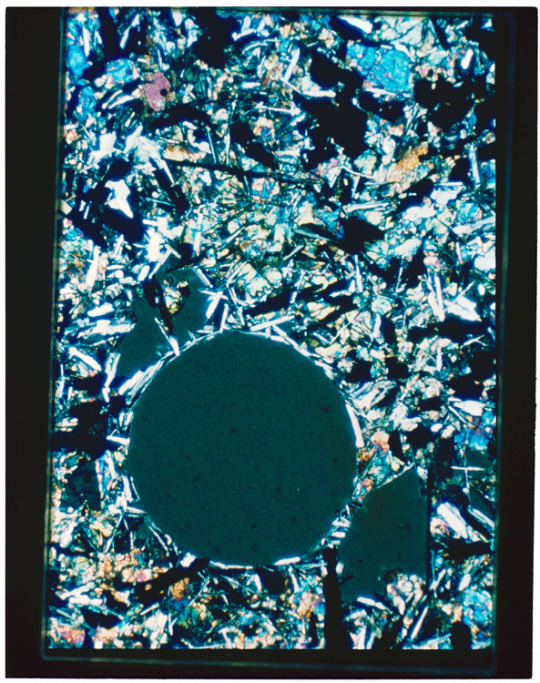

Photo

(top): Processing photograph of Apollo 11 samples 10017, 10019, and 10020. Image courtesy NASA/Johnson Space Center

(center): Processing photograph showing sample 10020 in vacuum vault. Image courtesy NASA/Johnson Space Center

(bottom left): Apollo 11 sample 10020, thin section C in transmitted light. Image courtesy NASA/Johnson Space Center

(bottom right): Apollo 11 sample 10020, thin section C in crossed Nicols light. Image courtesy NASA/Johnson Space Center

Over the course of six moonwalks, the Apollo astronauts brought back 842 pounds of rocks, dust, and core samples from the Moon. After splashdown, lunar rock samples were taken to NASA’s Lunar Receiving Laboratory in Houston, Texas, where they were processed and analyzed.

NASA scientists examined thin slices—about one-thousandth of an inch thick—of the lunar rock samples under a petrographic (literally “rock-recording”) microscope. The left photomicrograph was taken using regular transmitted light. The right one was made under cross-polarized, or “crossed Nicols” light, produced by passing light through two perpendicular polarizing Nicols prisms before it reaches the sample. Holes look black, while the minerals that make up the sample appear vibrantly colored, allowing scientists to identify the rock’s individual components by color.

To see more photographs and photomicrographs of lunar rock samples, visit NASA's Lunar Rocks and Soils database at curator.jsc.nasa.gov/lunar.

#nasa#Apollo 11#lunar rock#moon rock#photomicrograph#center for creative photography#Astronomical#beyond#twentieth century#20th century

21 notes

·

View notes

Photo

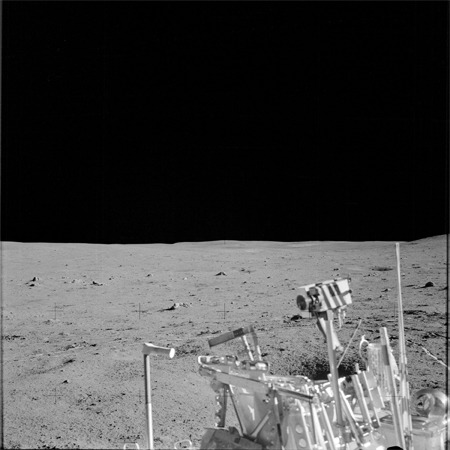

NASA/Apollo 14

AS14-64-9048, AS14-64-9055, AS14-64-9058, AS14-64-9103, AS14-64-9120, AS14-64-9201, 1971

Gelatin silver prints

Images courtesy Lunar and Planetary Institute/NASA

The Apollo astronauts’ bulky suits, along with the moon’s weak gravity, made the simplest movements tiring and awkward. To conserve time and energy, the act of photographing was simplified as much as possible. While the astronauts were equipped with handheld Hasselblad cameras, during moonwalks the cameras were mounted to chest brackets on their suits. Because sunlight was so bright during the lunar day, the astronauts kept their cameras at a fixed small aperture setting, allowing for great depth of field. Film was wound automatically with a motor drive, and the shutter was controlled by a trigger mechanism. Since the astronauts could not afford to take extra weight on their return trip to the command module, they left their Hasselblads, with custom Zeiss lenses, on the surface of the Moon.

The prints on view in the To the Moon gallery are on loan from the University of Arizona Space Imagery Center. The selection of images is recreated here using digital scans of a different set of Apollo prints made by the Lunar and Planetary Institute in cooperation with NASA. To see the complete archive of over 25,000 digitized Apollo photographs, visit lpi.usra.edu/resources/apollo.

#NASA#Apollo 14#Lunar and Planetary Institute#moon#moon landing#gelatin silver print#twentieth century#20th century#center for creative photography#Astronomical#To the Moon

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

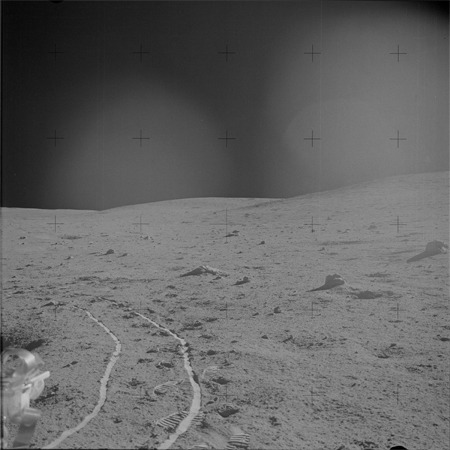

NASA/Apollo 12

AS12-48-7024, AS12-48-7034, AS12-48-7037, AS12-48-7160, AS12-48-7099, AS12-49-7243, 1969

Gelatin silver prints

Images courtesy Lunar and Planetary Institute/NASA

Moon dust, each granule a relic of millions of years of shattering impacts, reflected light unpredictably. (The dust also clung to any surface it touched, including space suits, camera lenses, and instruments; once embedded, it was nearly impossible to remove.) For a visual reference point, the Apollo astronauts carried color charts that they photographed on the lunar surface.

The prints on view in the To the Moon gallery are on loan from the University of Arizona Space Imagery Center. The selection of images is recreated here using digital scans of a different set of Apollo prints made by the Lunar and Planetary Institute in cooperation with NASA. To see the complete archive of over 25,000 digitized Apollo photographs, visit lpi.usra.edu/resources/apollo.

#NASA#Apollo 12#Lunar and Planetary Institute#moon#moon landing#Surveyor 3#twentieth century#20th century#center for creative photography#Astronomical#To the Moon#gelatin silver print

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

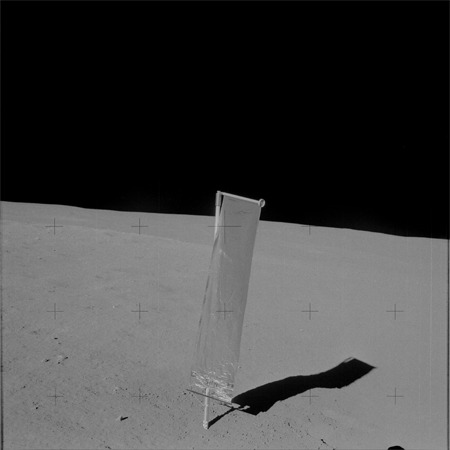

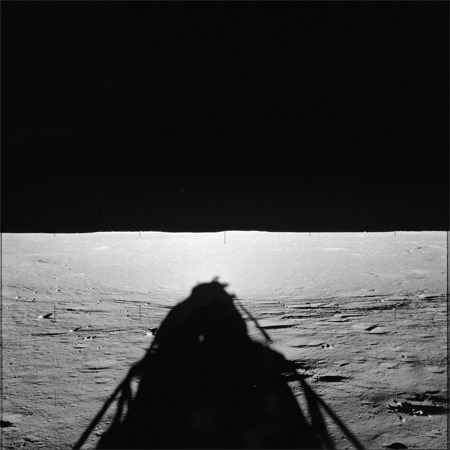

NASA/Apollo 11

AS11-38-5725, AS11-39-5757, AS11-39-5778, AS11-39-6794, AS11-39-5800, AS11-39-5815, 1969

Gelatin silver prints

Images courtesy Lunar and Planetary Institute/NASA

Apollo astronauts faced a landscape marked by colossal forces, yet one of eerie clarity and unusual actions of light. Because the Moon has practically no atmosphere to refract light, the sky was a palpable, velvety black during the day, while the Moon’s surface appeared floodlit. Moon rocks that on Earth would look charcoal-colored were instead a bright, silvery gray.

The prints on view in the To the Moon gallery are on loan from the University of Arizona Space Imagery Center. The selection of images is recreated here using digital scans of a different set of Apollo prints made by the Lunar and Planetary Institute in cooperation with NASA. To see the complete archive of over 25,000 digitized Apollo photographs, visit lpi.usra.edu/resources/apollo.

14 notes

·

View notes