Text

What people think why i became a bookbinder: Oh she wants to explore her artistic horizon with those pretty leather bound books of hers. She even gives them out as gifts to her friends. It most likely helps her with anxiety or maybe she just wanted a more special costume made notebook.

Why I actually became a bookbinder: I just illegally downloaded and printed out several of my favourite fanfics and books and started binding them into books cuz I love reading them but looking at screens for too long gives me headaches.

128K notes

·

View notes

Text

“Getting” yourself to write

Yesterday, I was trawling iTunes for a decent podcast about writing. After a while, I gave up, because 90% of them talked incessantly about “self-discipline,” “making writing a habit,” “getting your butt in the chair,” “getting yourself to write.” To me, that’s six flavors of fucked up.

Okay, yes—I see why we might want to “make writing a habit.” If we want to finish anything, we’ll have to write at least semi-regularly. In practical terms, I get it.

But maybe before we force our butts into chairs, we should ask why it’s so hard to “get” ourselves to write. We aren’t deranged; our brains say “I don’t want to do this” for a reason. We should take that reason seriously.

Most of us resist writing because it hurts and it’s hard. Well, you say, writing isn’t supposed to be easy—but there’s hard, and then there’s hard. For many of us, sitting down to write feels like being asked to solve a problem that is both urgent and unsolvable—“I have to, but it’s impossible, but I have to, but it’s impossible.” It feels fucking awful, so naturally we avoid it.

We can’t “make writing a habit,” then, until we make it less painful. Something we don’t just “get” ourselves to do.

The “make writing a habit” people are trying to do that, in their way. If you do something regularly, the theory goes, you stop dreading it with such special intensity because it just becomes a thing you do. But my god, if you’re still in that “dreading it” phase and someone tells you to “make writing a habit,” that sounds horrible.

So many of us already dismiss our own pain constantly. If we turn writing into another occasion for mute suffering, for numb and joyless endurance, we 1) will not write more, and 2) should not write more, because we should not intentionally hurt ourselves.

Seriously. If you want to write more, don’t ask, “how can I make myself write?” Ask, “why is writing so painful for me and how can I ease that pain?” Show some compassion for yourself. Forgive yourself for not being the person you wish you were and treat the person you are with some basic decency. Give yourself a fucking break for avoiding a thing that makes you feel awful.

Daniel José Older, in my favorite article on writing ever, has this to say to the people who admonish writers to write every day:

Here’s what stops more people from writing than anything else: shame. That creeping, nagging sense of ‘should be,’ ‘should have been,’ and ‘if only I had…’ Shame lives in the body, it clenches our muscles when we sit at the keyboard, takes up valuable mental space with useless, repetitive conversations. Shame, and the resulting paralysis, are what happen when the whole world drills into you that you should be writing every day and you’re not.

The antidote, he says, is to treat yourself kindly:

For me, writing always begins with self-forgiveness. I don’t sit down and rush headlong into the blank page. I make coffee. I put on a song I like. I drink the coffee, listen to the song. I don’t write. Beginning with forgiveness revolutionizes the writing process, returns its being to a journey of creativity rather than an exercise in self-flagellation. I forgive myself for not sitting down to write sooner, for taking yesterday off, for living my life. That shame? I release it. My body unclenches; a new lightness takes over once that burden has floated off. There is room, now, for story, idea, life.

Writing has the potential to bring us so much joy. Why else would we want to do it? But first we’ve got to unlearn the pain and dread and anxiety and shame attached to writing—not just so we can write more, but for our own sakes! Forget “making writing a habit”—how about “being less miserable”? That’s a worthy goal too!

Luckily, there are ways to do this. But before I get into them, please absorb this lesson: if you want to write, start by valuing your own well-being. Start by forgiving yourself. And listen to yourself when something hurts.

Next post: freewriting

Ask me a question or send me feedback! Podcast recommendations welcome…

41K notes

·

View notes

Text

Theme and Structure

When I was younger, I had a very fraught relationship with theme. I resented it. I didn’t like the idea that a story needed to teach a lesson in order to be valuable. I thought stories were inherently valuable on their own. I didn’t understand that a theme isn’t something that’s painted on at the end, it isn’t something that is tacked on to appease the snobs and English teachers and snobby English teachers. Theme is absolutely essential to a story. It is a component of every story just the same way that characters or plot are.

So, I understood the importance of theme, but I still didn’t understand how to actually incorporate it into a story, how to make sure it was baked in from the very beginning and not just slathered over the top.

I finally figured out a method that worked for me while I was thinking about character and story structure, because–of course–all these things are connected. I found a method that allowed me to incorporate theme into a story and use the theme to create an ending that feels satisfying and earned.

All of this may have been very obvious to other people, but if you’re having trouble wrapping your head around theme and want a concrete way to work it into your story, then this might help.

The theme and the emotional throughline are the same thing. The theme is something–some concept–that the character needs to understand, some part of them that is missing, and the story is a world that has been specially constructed to teach our character that concept and deliver them some wisdom that will help them in the end. Whether the character actually uses this wisdom is up to the writer (and the character).

Structurally, it can play out like this:

I. The Beginning–We don’t know the character at all. The character either doesn’t know what they are missing, or they know exactly what is missing but they don’t want to acknowledge it.

II. Holding Back-We progress through the story and we see the ways that whatever the character is missing is holding them back. Characters focus on what they want instead of what they need, they obfuscate, they focus on things that they prefer were their problem because they are easier to deal with than their actual problem.

III. Midpoint-Both the audience and the character understand what the character is missing, but the character either doesn’t know how to get it or has to undergo a struggle in order to get it.

IV. Attempts and Frustrations-The character finally understands what they need to do, but things get in their way. There are setbacks and losses and the character’s resolve is either strengthened or weakened.

V. Moment of Truth-This is the moment before the climax, when the hero finally understands the wisdom that has long been eluding them, they see what they have to do. This is the second major realization. The first was the midpoint when they saw what was wrong, this is the realization where they understand what they must do to fix it. This is the moment where they either decide to use their hard-won wisdom and become whole, or ignore what they have learned and remain incomplete.

VI. The Climax-The character either uses their new wisdom and succeeds or ignores it and fails, even if they win in whatever the actual plot is, if they ignore their wisdom it will be a pyrrhic victory.

VII. The Come Down-We see how the characters’ lives were improved by using their new wisdom or how their life is empty because they chose to ignore it.

Go to this link to see this method put in practice with a breakdown of my book, Eldest Son of an Eldest Son.

What do you guys think? Agree? Disagree? Let me know! And please let me know if there are any topics you would be interested in me covering.

228 notes

·

View notes

Text

the thing is, i think horror needs to have a little love. it needs to have an obsession. does the parasite in your body love you? it raises you from the dead, it sustains you. this is its body. this is your body. does the haunted house feel intruded upon? is it hungry? what is hatred but adoration?

66K notes

·

View notes

Text

Writing a novel when you imagine all you stories in film format is hard because there’s really no written equivalent of “lens flare” or “slow motion montage backed by Gregorian choir”

165K notes

·

View notes

Text

Heard that from a lecturer in my university, and I think it’s such a good advice, and I’ve never seen anybody talk about it so:

It is called a reverse outline.

Basically, you write your entire 1st draft, take a good moment reading all of it, and then start summarizing each chapter one by one in single paragraphs.

It helps you to identify which scenes are not actually necessary, analyze if a scene is well placed in that moment of the story - and if not, it can help placing the chapter earlier or later in the story -, helps identifying plot holes etc.

I thought of that as really helpful, specially if you, like me, is a gardener writer but still needs organization!

5K notes

·

View notes

Text

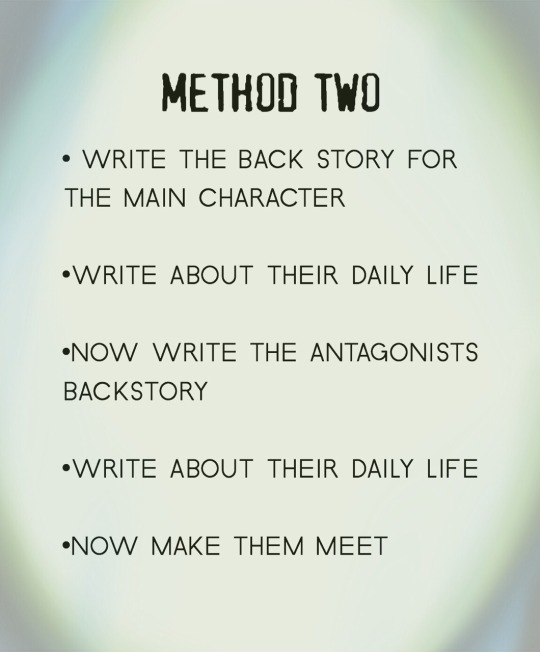

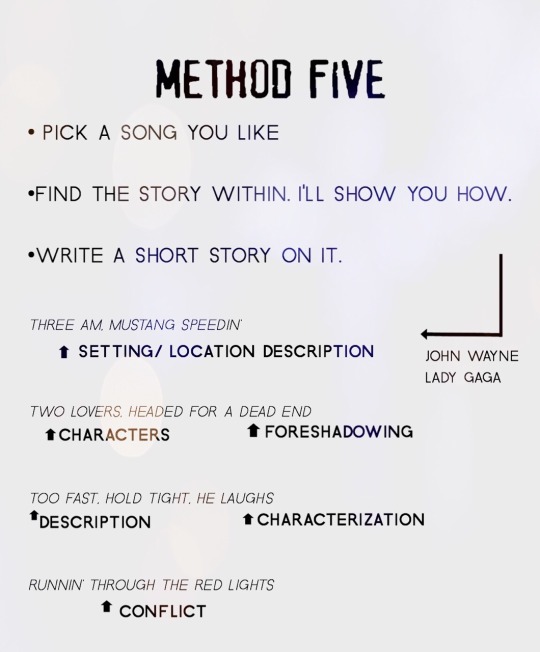

This is not an exhaustive list of ways to get jump started but these are a few of my favorites! Enjoy c:

5K notes

·

View notes

Text

I have this nebulous idea that the Marie Kondo method actually applies really well to editing the first complete draft of a story and I just...could write a whole essay about it but that might be all there is to it? Going through part by part and asking if this sparks joy and dropping it mercilessly into the discard doc if it doesn't???

15K notes

·

View notes

Text

How to Keep an Edit Notebook

In my How to Edit a First Draft post, I mentioned something I call an edit notebook. Edit notebooks help you figure out what level of revisions your WIP requires, and exactly what is wrong with your manuscript. I use a 3-subject notebook per project, and a section per draft. An edit notebook is composed of a few parts:

1. Chapter-By-Chapter Notes

this is where you read through your manuscript and take notes on scenes

you usually want to note what happens in the chapter, how well it is written, and whether or not it is relevant to the plot

2. Overall Plot Notes

these also happen while you’re reading over your WIP

I usually made them in-between sections of chapters, but some I made while reading

these include things you’d like to add/change/remove from the plot

3. Analysis (Note: This is the most important part! The whole point of an edit notebook is to figure out how much editing you actually have to do. I sort these into different “levels.”)

Novel-Level: If all your notes say “delete scene,” “scrap,” “poorly written,” “unecessary” etc., then you’re probably looking at a full-on rewrite. Pull on your big-boy pants, grab a cup of coffee, and start re-plotting.

Chapter-Level: If your notes are less about how bad the plot is and more about how bad the writing quality is, then your revisions should focus more on pacing, the order of your scenes, point of view, and rewriting/recrafting scenes to make them better.

Line-Level: If the plot is flawless, there aren’t any plot holes or dull moments to be accounted for, just grammar/sentence structure problems, then this is when you print out your novel and go through it with a red pen.

Of course, there are steps in-between, and sometimes you’ll spend several drafts in one level. But in general, this is what you should be looking for!

4. Redrafting (Especially important when making novel-level edits, which is probably what you’re dealing with when you have a first draft)

list possible scene ideas, brainstorm

try to write out your new plot, or at least the “tentpole” moments (the important events)

from there, fill in what goes in-between the major events

remember, you can’t really know if it works or not until you actually write it!

5. Reoutlining

I like to make a summary sheet (below the cut), which ideally includes your major plot points, major flashbacks, subplots, symbols, conflicts, resolutions, and the story arc (as well as anything else you want to keep track of)

plot out timelines/arcs for characters

basically do whatever you would normally do before you begin writing something new. Except, this isn’t new! You know what you’re doing and where you’re going this time. You got this.

Keep reading

5K notes

·

View notes

Note

G'morning :D

I wanted to ask how do you handle writer's block? I've been trying to write a scene for half an hour and it just doesn't come out AAAAAAAAA

Grrr, writer's block is THE WORST!!!

I have a couple of things that I do.

a) I'll turn to my pre-writing notes (and if I don't have any I'll make some) and look at what I had originally planned for before, during, and after that scene. This allows me to remember the vision that I have, and maybe add a few more bullet points to create a guideline for the scene I'm struggling with. This way it's less work and more like filling in the gaps.

b) If that doesn't work, I may turn to my source of inspiration for the fic or look up some inspiration. This can be anything from songs, to pictures, to aesthetic boards. Just something that will get me that spark again of inspiration again.

c) cry and glare at the blinking cursor

d) Sometimes, it's just not there for me to write that scene in that moment. So, I'll make bullet points of the ideas I have for whatever is left of that fic or chapter where I currently am, and step away from my laptop and just rest and rejuvenate with some self-care (shower, face mask, a walk) and come back to it and try again afterwards.

Hope these help!

40 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Part I: Outlining.

Fore Note: This is the process I’m currently using to outline, write, and edit my novels. There are a million different ways to journey through the writing process, and the only ‘correct’ one is the one that works for you in the moment. Everyone’s writing process is a little bit different, and most writers (including myself) change theirs every few books as they figure out what techniques are most beneficial to them and for certain types of novels.

I’m a pretty big outliner when it comes to complex novels and series, but simpler novels and novellas I prefer to wing. Below is the process I would go through if I were doing a full, detailed outline. For simple plots, I skip steps 3-5.

1. Brainstorming. This can involve pretty much anything, including but not limited to…

Daydreaming.

Inspirational pictures.

Science articles.

Life experiences.

Any of these eight exercises.

The key is to write down everything you might use, just in case in you need it. You can throw out a bad idea later but you can’t utilize a good idea you’ve forgotten.

Keep reading

514 notes

·

View notes

Text

Plotting Methods for Meticulous Plotters

A Guide for the Seasoned and the Not-So-Plot Savvy

This is a subject that a lot of writers tend to struggle with. They have ideas, great ideas, but are uncertain how to string them together into a solid plot. There are many methods that have been devised to do so, and most seem to be based on something you might remember:

The 5 Point Method

This is your basic plot diagram:

Exposition – This is the beginning of your story. This is where you introduce your character (s), establish a setting, and also present your main conflict.

Rising Action – Your story now begins to build. There are often multiple key events that occur where your main character may be faced with a new problem he has to solve or an unexpected event is thrust at him.

Climax – Everything you’ve been writing has been leading up to this moment. This is going to be the most exciting part of your story where your main character faces the main conflict and overcomes it.

Falling Action – This is mostly tying up loose ends after your main conflict is resolved. They are minor things that weren’t nearly as important as the main conflict, but still needed to be dealt with.

Resolution –The end of the story.

This is probably the easiest way to remember how to string together a single (or multiple) plots. It may be easier for some to define the main plot as the central conflict, or the thing that’s causing your main character a huge problem/is his goal.

The 8 Point Method

This method is used to write both novels and film scripts, and further breaks down the 5 Point Method. From the book Write a Novel and Get It Published: A Teach Yourself Guide by Nigel Watts:

Stasis – The opening where the story takes place. Here you introduce your main character and establish a setting (Watts defines it as an “everyday” setting, something normal, but it can be whatever you want).

Trigger or Inciting Incident – The event that changes your character’s life an propels your story forward. This is where you introduce the main conflict.

The Quest – The result of the event. What does your character do? How does he react?

Surprise – This section takes of the middle of the story and involves all of the little setbacks and unexpected events that occur to the main character as he tries to fix the problems he’s faced with and/or achieve his goal. This is where you as an author get to throw complication, both horrible and wonderful, at your protagonist and see what happens.

Critical Choice –At some point your character is going to be faced with making a decision that’s not only going to test him as individual, but reveal who he truly is to the audience. This cannot be something that happens by chance. The character must make a choice.

Climax – This is the result of the main character’s critical choice, and should be the highest point of tension in the story.

Reversal – The consequence of the choice and climax that changes the status of your protagonist, whatever that may be. It could make him a king, a murderer, or whatever else you like but it has to make sense with the rest of the story.

Resolution – The end of the story where loose ends are tied up. You’re allowed to leave things unresolved if you intend to write a sequel, but the story itself should be stand alone.

Three Act Structure

While this method is usually for screenplays, it is also used in writing novels (for instance The Hunger Games novels are split up into three acts). From the The Screen Writer’s Workbook by Syd Field: Acts 1 and 3 should be about the same length while Act 2 should be double. For instance if you were writing a screenplay for a two hour film Acts 1 and 3 would be 30 minutes each while Act 2 would be 60 minutes.

Act 1, Set Up – This contains the inciting incident and a major plot point towards the end. The plot point here leads into the second act and is when the protagonist decides to take on the problem he’s faced with.

Act 2, Confrontation – This contains the midpoint of the story, all of the little things that go wrong for the protagonist, and a major plot point towards the end that propels the story into the third act. This is the critical choice the character must make.

Act 3, Resolution – This is where the climax occurs as well as the events that tie up the end of the story.

Another way to look at this method is that there are actually three major plot points, or disasters, that move the plot forward. The first is at the end of Act 1, the second is in the middle of Act 2, and the third is at the end of Act 2.

The Snowflake Method

A “top-down” method by Randy Ingermanson that breaks novel writing down into basic parts, building upon each one. You can find his page on the method here. His ten steps:

Write a single sentence to summarize your novel.

Write a paragraph that expands upon that sentence, including the story set up, the major conflicts, and the ending.

Define your major characters and write a summary sheet corresponding to each one that includes: the character’s name, their story arc, their motivation and goal, their conflict, and their epiphany (what they will learn).

Expand each sentence of your summary paragraph in Step 2 into its own paragraph.

Write a one page description of your major characters and a half page description of less important characters.

Expand each paragraph in Step 4 into a page each.

Expand each character description into full-fledged character charts telling everything there is to know about the characters.

Make a spreadsheet of all of the scenes you want to include in the novel.

Begin writing the narrative description of the story, taking each line from the spreadsheet and expanding the scenes with more details.

Begin writing your first draft.

Wing It

This is what I do. I tend to keep in mind the basic structure of the 5 Point Method and just roll with whatever ideas come my way. I’ve never been a fan of outlines, or any other type of organization. According to George R.R. Martin, I’ve always been a gardener, not an architect when it comes to writing. I don’t plan, I just come up with ideas and let them grow. Of course, this may not work for some of you, so here are some methods of organization:

Outlines

Notecards

Spreadsheets

Lists

Character Sheets

And if all else fails, you can fall on the advice of the great Chuck Wendig: 25 Ways to Plot and Prep Your Story.

Remember, none of the methods above are set in stone. They are only guidelines to help you finally write that novel.

-Morgan

12K notes

·

View notes

Note

Hey! I’m struggling with describing setting. I read some of your Master Lists on it as well as researched it on my own, but my only question is when do I describe the setting and how much information is too much? and what information is necessary? (i.e when describing a character, i know you should show, not tell. how do I do this through setting?) Thanks in advance!!

What Details to Include When Describing Setting

With setting, you only need to describe it in two situations:

1) Because the reader needs those details to understand an important character or something that’s going to happen in the story.

Let’s say you’re writing a story about a modern day high school student who falls in love with a werewolf, and the first scene is your character walking into the kitchen and getting into an argument with his mom. Do you need to describe what the kitchen looks like? Well, that depends. Everyone knows what a kitchen looks like, so unless there’s something unusual or important about the way the kitchen looks that the reader needs to know, then no... you don’t need to describe the kitchen. But, let’s say your character comes from a family of witches who were cursed to live in the woods and keep to the fringes of society. And, as a result, your character lives in a ramshackle but enchanted old cottage where dinner is cooked in an old kitchen hearth where herbs for spells are drying over the fire, and kettles of potion are boiling on the flames. This would obviously be important for your reader to know, not only because imagining an average kitchen isn’t going to cut it here, but because these details tell us something important about who your character is and what their back story might be.

2) To set the stage for the current scene.

Let’s say there’s a scene where your character goes to prom, and to demonstrate his magic to his werewolf beau, he animates a bunch of paper butterflies decorating the walls so that they’re flying around the dancing students. It would be a little confusing to the reader if you don’t describe the decor of this prom, and suddenly you’re describing these paper butterflies coming to life. What paper butterflies? In this case, you would certainly want to establish ahead of time that the decor includes paper butterflies stuck to the walls. That detail is important for the reader to know. And, since you probably don’t want to say, “The gym was all decked out for prom with paper butterflies on the wall...” and leave it at that, you could include other decor to help the reader imagine what it looks like, even if those other details aren’t in themselves important. It would be much more interesting to imagine the paper butterflies fluttering among twinkling fairy lights, blue and silver metallic streamers, and silver balloons than to just imagine them fluttering around a nondescript gym.

So, focus on details that are important. If a detail is important, include it, if it’s not and doesn’t add anything to the story, skip it. If the detail is something obvious like what the inside of a car looks like--and there’s nothing unusual about the inside of that car--skip it.

I hope that helps!

•••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••

Have a writing question? My inbox is always open!

Visit my FAQ

See my Master List of Top Posts

Go to ko-fi.com/wqa to buy me coffee or see my commissions!

77 notes

·

View notes

Text

Oh my gosh. I just found this website that walks you though creating a believable society. It breaks each facet down into individual questions and makes it so simple! It seems really helpful for worldbuilding!

104K notes

·

View notes

Note

hi, i wanted to use sirens in my wip and to my shock, all myth resources describe sirens as part bird who have feet and sometimes wings. how in the world did these creatures get combined with mermaids in every piece of pure fiction written or filmed. do you know any fiction that even uses the part bird sirens for reference?

Hello!

How in the world, indeed! In order to track down the beginnings of the conflation of sirens with sexy half-human, half-fish ladies, it is necessary to become some kind of mad sleuth, tracking down clues and piecing together the long, winding trail of sirens to mermaids.

First, let’s look at the ultimate culprit for confusing the winged, harpy-reminiscent sirens with their ocean-dwelling mermaids cousins: popular culture. The origin of the sirens in mythology is their depiction in Homer’s Odyssey, where there is really nothing to tell us what they looked like, but rather what lure they offered to Odysseus: they had the gift of prophecy, and they sang to him of their knowledge of things to come, which, if you’re Odysseus, a Greek who makes his bread and butter on knowing all the things, is more than a little seductive. The Audubon (of all publications) interviewed Emily Wilson, a Greek scholar, about it and the article is extremely informative, if you want to dive a bit deeper into birds and their association with death and wisdom in ancient Mediterranean cultures.

The possibilities for speculation are endless and as seductive as the sirens’ offering of secret knowledge. Homer had the sirens’ voices being carried over the water, so establishing a connection to the ocean; though we know the sirens lived on an island covered in the bones of the seafarers they had lured to their death, it’s easy to imagine them beneath the waves.

The sirens have some connection to the water in their parentage: they were generally given as the daughters of a muse (usually Melpomene, muse of song) and Achelous, god of all the rivers in all the world. And though Homer gives us no information about the sirens’ physical aspect, they were popularly depicted as half-woman, half-bird, similar to the Harpies, granddaughters of Pontus (the Sea) and Ge (Earth), who also birthed the Nereids, or water nymphs. One of the Nereids, Nereus, was the “old man of the sea” and his daughter, Tethys, was a shapeshifter.

In the 2nd century AD, a Roman author recounted how the sirens had once been handmaidens of Persephone, and when Hades stole her away, Demeter in her grief transformed the young women into birds with human faces, so that they might fly over the world and search for her lost daughter.

Most every world culture has depictions of mermaids in its mythology, including the Caribbean, Hinduism, China and the British Isles. Russian rusalkas, spirits of the drowned dead, appear as beautifully pale young women. The African deity Mami Wata has lustrous brown skin, ebony hair, and sometimes the writhing tail of fish. Both use their appealing physical aspects and voices to lure unwary humans to their death—much as the sirens did—but offer the temptation of their bodies rather than knowledge or secrets.

During the 18th, 19th, and early 20th century, a resurgence of interest in ancient Rome and Greece coloured the cultural and artistic landscape of Europe and Great Britain. In 1837, Hans Christian Andersen published The Little Mermaid. In 1876, German composer Richard Wagner premiered his four-drama cycle Der Ring des Nibelungen, which included characters called “the Rhinemaidens”—seductive and elusive water nymphs who “lured men away”. Mermaids rose to the fore of European popular culture. A spate of paintings from around that time, continuing into the early 1900s, from the neoclassical movement, took artistic liberties with the myth of the sirens—mixing and matching physical attributes.

In 1891, the famous painter John William Waterhouse depicted Ulysses (Odysseus) on his boat, surrounded by the winged and taloned sirens, familiar from the painting on Greek vases in “Ulysses and the Sirens”. But some years earlier, English artist William Etty and French painter Léon Belly, had both depicted their own versions of the famous scene. In Etty’s painting “The Sirens and Ulysses” (1837), the sirens are female, completely human, and explicitly meant to represent sensual temptation. In Belly’s 1867 work, “Les sirènes” (also called “Ulysses and the Sirens” in English), the sirens are similarly voluptuous and entirely human, but they are rising up out of the ocean or flailing about in the water as they try in vain to grasp Odysseus. A year later, in 1868, Marie Francois Firmin Girard presents the sirens in “Le chant des sirènes”, again as beautiful women, playing traditional Greek instruments and trying to lure a ship to their rocky island.

By 1900, John William Waterhouse produced another work simply entitled “The Siren”, in which a young, beautiful woman holding a Greek lyre (chelys) sits on a rocky outcrop, overlooking storm-darkened seas. Visible in the background are bits of flotsam from an apparent shipwreck; she looks down on a young man in the water below her, who is struggling to stay afloat. Her features are predominantly humanoid, but just visible around her calves are the characteristically iridescent pattern of scales.

By 1909, English painter Herbert James Draper produced his vision of The Odyssey’s sirens in “Ulysses and the Sirens” (so original)—and they are explicitly fishy. Beautiful young women are rising up out of the waves, clutching at Odysseus’ boat, and one’s lower half is entirely covered in the scales and fins of fish. In 1910, we get Howard Pyle’s “The Mermaid”, in which a woman rises up from the foam, clutchin a man wrapped in a toga-style garment and wearing a red Phrygian-style cap remarkably similar to that of Ulysses’ in Belly’s painting.

Wikipedia has an archived list of sirens’ appearances in modern popular culture that you might find useful, although most depictions seem to focus primarily on their seductive qualities. Oral tradition and art combine to create a blending of myths and attributes in the popular consciousness. We know to be sure that sirens originated with the Greeks; where they ended up was thanks to a confluence of cultural influence that restyled their seductiveness into something more physical, but no less mysterious, to us than the depths of the ocean.

Bonne chance,

Renée

212 notes

·

View notes

Text

Character Arc but no Plot?

You’re in a better situation than you think.

For Character primary stories, your character arc truly IS your plot. Your plot begins with your character at point A and ends with your character at point B (or still at point A in spite of everything if you’re writing a tragedy).

Ok, sure, sounds easy when I say that but what does it actually mean? Here is where structure is your friend, the more you know about standard story structure the more you know how to move a character from A to B.

Point A is how the character is. It shows them as they are, shows their aspirations, and shows their flaws. You get about 25% of the story to show all that. So if it’s really short you get one scene, if it’s really long you get a bunch to really show it.

At about the 25% point something very important happens and for whatever reason you determine, your character can’t be the same as they were at point A any more. Doing so is going to get them killed emotionally.

For the next 25% of the story or so, their natural Aish instincts are going to get them spanked as they try and change as little as possible and the world seems to conspire to punish them for it. The number of scenes you did for A, you mirror them here and show them going to hell.

At the 50% markish something even more important happens, how bad your character thought it was to be A, it’s so much worse. Worse than killing them? Yes. It’s so bad that now the character tentatively sticks their toes into Bish territory.

For 25% the character ever more actively embraces being B to cope with the problems coming at them. The world doubles down to try and punish them but the more B they become, the harder it is for the world to hurt them.

Until at about the 75% point one last really important slap in the face happens and it is suddenly clear that there is both a cost to being B and if your character takes even one more step, they can never go back to A. And yet, with all that, the positive character goes forward.

For the final 25% of the story, it is final exam time. Does the character understand what it means to be B, can they stay B in spite of a challenge that should turn them back to A, Are they truly committed to being B for the long haul? For a happy ending for a positive character, the answer is always yes. And so, knowing utterly that the character shall henceforth be B, the story ends.

So the first question is: what is A and what is B. That’s the character arc. A is how they are at story’s start. B is how they are at story’s end. If your character is learning how to love as an adult. Then A is them only knowing how to love like a child. And B is them showing emotional maturity. The challenges at each successive 25% mark is challenging the flaws inherent to being A. This is why two writers can write the exact same story and have it come out radically different. What I see as the inherent flaws in someone’s inability to love like an adult will probably not be the flaws you pick. Our lives are different enough that we’ll focus on different criteria. But essentially, no matter what you choose as A and B, you are showing A as fundamentally flawed by challenging its weaknesses and B as one solution to those challenges. As long as you know the basic flaws of the character, you can lay that into this most basic form of structure to tell you approximately what your plot should be.

58 notes

·

View notes