Text

Chapter 40: The Crap Cave

“Dante! You found us!” Clio said as I hovered awkwardly in the doorway of the art room that first day of school during lunch period.

She bounded over and grabbed my elbow to draw me into the oddly dark classroom. The overhead lights were all off, the window shades partially drawn down and gloomy pop music I vaguely recognized as The Cure droned from a cassette player. About ten kids were sprawled out around the room, most of them sporting various degrees of punk/goth/New Waver style. Two corset-clad girls in billowy skirts drew intricate designs on each other’s arms in black pen; a couple dressed in “normal” clothes was making out with gusto in the corner by the potter wheels; a boy wearing all black continually skimmed his pointer finger over the top of a Bic lighter flame; and the rest were eating lunch, chatting, scribbling in notepads or singing along to the music. Clio flicked the overhead lights a few times to get everyone’s attention, eliciting a few winces and hisses and boos from the group.

“Everyone, listen up, this is Dante. He’s new. He’s from Texas, but try not to hold that against him. He’s a brilliant artist. Dante, this is everyone. That’s Raija, Jane, Sachi, Fletch and Kelly back there sucking face, Joseph, Ann, Dave, Forest and Vee.”

I was greeted with a few head nods and finger waves, except for the couple making out who kept at it with sloppy yet admirable enthusiasm. Everyone went back to their conversations as Clio led me closer to the girls she’d pointed out as being named Jane and Sachi.

“So, Dante from Texas, welcome to 'The Crap Cave’”, Clio said using air quotes. “We have lit mag meetings here and also make our own ‘zines and stuff. Raija’s mom Ms. B is the art teacher—she just stepped out for a minute—so she doesn’t care if we hang out here as long as we don’t you know, perform ritual animal sacrifices or set anything on fire. Again.” She coughed pointedly in the direction of the boy with the lighter seated a few desks down from us and the girls chuckled. Seeing my apparent confusion she said, “See, Joseph’s a bit of a pyro and went through a destruction of property phase last year, didn’t you, Jo-Jo?” The boy in question grinned slyly up at us. “But he’s got it under control now,” Clio continued. “He channels his urges into sculptures where he can use an actual blowtorch from woodshop.”

“Blowtorches rule,” he said and cast me one more glance before focusing all his attention back to his lighter and intrepid pointer finger. I couldn’t help but notice that all his fingernails were painted black and he was wearing eyeliner and dark lipstick like the girls.

I pulled my gaze away from him, not wanting to stare too hard and be rude. “What did you call this room? The ‘crap cave’?” I asked Clio. “Did I hear that right?”

“Oh yeah, you heard me right.”

“Do I even want to know?”

Clio laughed. “Don’t look so scared, we know how to use the bathrooms like everyone else. It’s a sort of long story. You ever hear of The Batcave?”

“You mean like from Bat Man comics?”

“No. Well yes, but no. Same but different. The Batcave is this famous club in London for people like us. Bauhaus, Robert Smith, Siouxie, Nick Cave, Specimen all hang out and play there. Jane actually got to go there this summer, that lucky bitch,” Clio knocked Jane’s shoulder with friendly admiration. “So we kind of started calling it that in homage to the club like a year ago. But then the school had this gross mouse problem and their little poops were, like, this constant presence in our lives, so somewhere along the line we started calling it ‘The Crap Cave’ instead. Because that's how we roll.”

“The mice were perfect and adorable, not gross,” Sachi said.

“Sachi, no. Just no. The mice themselves might have been cute but their poops definitely weren’t.”

The two girls bantered about whether the mice should have been saved and kept as pets or if they were indeed an icky health hazard while I took everyone in, trying not to gawk, and sat down to eat my packed lunch. I was fascinated by the group’s collective style: a motley assortment of teased and spiked dyed hair, leather jackets, ripped band t-shirts, corsets and lace, fishnets, heavy boots, winged eyeliner, black lipstick and nail polish, powdered white faces, spiky hardware chain jewelry mixed with rosaries, crosses and pentagram necklaces. Some of the boys were even wearing makeup, which was something you hardly ever saw in El Paso. Joseph, the pyro boy, was particularly fascinating to me. His raven hair was teased out as much as Clio’s and his dramatic eye makeup accentuated his blue eyes and delicate, almost pretty features. The flame from his Bic lighter cast a warm glow on his ghostly pale skin.

Clio must have caught me staring because she leaned in close to my ear and said, “Don’t worry, Dante, we might look at little scary but we don’t bite. At least most of us don’t. Forest over there is saving up to get his teeth filed, but it’s not for blood sucking purposes. It’s because it’ll look badass.”

“Wow. My old school in El Paso was a Catholic private school so we all had to wear uniforms. It’s so cool you can wear whatever you want here. And be whoever you want. Do you all make your own clothes? I love your corsets,” I said to Jane and Sachi.

The girls grinned at me with approval and Clio said, “I knew you were a good egg, Dante. Jane made the corsets. She’s an amazing designer and sewer. I think the rest of us get by with thrift stores, hot glue and a crapload of paperclips.”

“I’ve never really thought about my clothes before,” I said. “But now I feel so boring compared to you all.”

“Aw, there’s nothing wrong with being a normie,” Clio said and patted me on the back. “It doesn’t make you boring.”

“Well, if you want to try something new, let me know,” Jane said. “Jo-Jo’s my twin brother. I make stuff for him all the time. Cravats, vests, things like that. I’m sure he’d let you borrow something.”

“Wow, thanks. You think I’d look good?”

“Yeah, for sure. But don’t let us pressure you. We dress like this because it feels right, right? But it’s not for everyone.”

The girls nodded.

“How did you all know you wanted to get into goth stuff?” I asked.

Jane said, “Well, for me, growing up I loved making clothes and dressing up since forever. Halloween was my always my favorite holiday. I was obsessed, like obsessed. Like I’d start planning my costume and how to decorate the house six months in advance. And after it was over each year, the next day I’d get so sad and cry for days and beg my mom to keep the decorations up and let me keep wearing a cape or whatever to school every day. So when I figured out that I could dress however I wanted whenever I wanted and basically have Halloween all year round and have my clothes express how I feel inside all the time, it was like a big weight was lifted.”

“Do people make fun of you?”

“I mean, sure, dicks are dicks,” Jane said.

“We get all sorts of ignorant comments at school, on the street, wherever. Like…‘Hey Morticia, Halloween is over,’” Clio lowered her voice to a dopey male grumble.

“Or ‘Errr….Do you sleep in a coffin?’” Jane said.

“Or ‘You look pretty hot for a dead girl!’” Sachi said.

“Or my personal favorite, the classic ‘Going to a funeral?’” Clio said with an epic eyeroll. “Yeah, your funeral if you don’t shut up about it. Please. But there are lots of people who aren’t asshats and you can just ignore the losers.”

“Yeah,” Sachi said. “People say things like ‘Oh, you’d look so pretty if you didn’t dress like that’ but this is how I feel pretty and beautiful. I didn’t feel right before. Now I feel good. Right. Like myself.”

“Raija’s mom is super cool because she’s an old hippie and gets it,” Clio said. “But my mom is still waiting and praying for the day when I let her dress me all in pink pouffy dresses again. Sorry Anita, not gonna happen.” There was an edge to Clio’s voice when she talked about her mom that I hadn’t heard from her yet. It made me wonder what her home life was like.

Sachi said, “Yeah, my parents were all worried at first that I was depressed and wanting to kill myself. They tried to have an intervention with all my aunties and cousins. ‘We’re worried about you, Sachi.’ ‘This isn’t the real you.’ Um, first off, yes it is. And second off, I’m so much happier now than before when I felt like a fake.”

“Yeah, people think that we do this for attention or as a cry for help or because we’re suicidal or worship Satan or are in a cult, but that’s not true at all,” Jane said. “I started making clothes for myself when I was ten. This isn’t a ‘phase’. I’m not going to just grow out of it.”

“And finding people who are into the same bands and fashion and movies and everything makes putting up with all the weird looks and comments easier. We’re here for each other, ” Sachi said.

“And sure, we get attention,” Clio said, “because we stand out with our awesome amazingness. But it’s not like we do it for attention.”

“Yeah, I totally get it.” I said. “I think it’s great.”

The girls smiled at me and I wondered how it would feel to dress like them, if that would feel ‘right’ for me or not. I understood what Sachi had said about feeling like a fake, though, and not liking how that made me feel. I felt that way when I used to tell people my name was Dan and not Dante. I felt that way still, a little. Because I didn’t quite know what it meant to be totally free and open with myself and the world and the universe. Not when it came to the biggest secret I had. In El Paso, I felt like I already stood out by not looking Mexican enough, by liking art and poetry and books and astronomy too much. It was enough to blend in and not get teased or bullied for being a little strange. Now I wondered if I flipped the script and really tried to stand out—if I dressed all in black and put on makeup and spiked my hair and embraced my innate weirdness—if that would make me feel more like me. It might make me feel tough and cool and badass for a little while, but I doubted it would make me feel more like myself the way it did for this group. How did I know, though? I’d never tried it before.

I wondered what Ari would think of my new friends. I bet he’d like them. And then I wondered what Ari would look like in black nail polish and eyeliner. I bet he’d look like a dark glamorous rock star. The thought did funny things to my insides.

Then the art teacher, Ms. Baldwin a.k.a. Raija’s mom, came in. She had gray hair in a long braid all the way down her back and wore a long flowy dress and bangle bracelets. She turned the overhead lights on and said, “Hey darklings, the cruel daylight beckons. Gotta get ready for the next class. Lunch is over in five. And you two, yoo-hoo, Earth to Fletch and Kelly! Please rein in your raging hormones during lunch if at all humanly possible? I can’t have anyone getting pregnant on school grounds.” Everyone cracked up at that and Fletch and Kelly turned beet red but finally disentangled their entwined limbs (and tongues).

I had an art class with Ms. Baldwin later in the day so I introduced myself.

“Hi, I’m Dante Quintana, I’m in your painting class during sixth period.”

“Dante, it’s so nice to meet you. You’re new, yes? This lot showing you the ropes?”

“Yes, Clio invited me to eat lunch with her and be part of lit mag.”

“That would be lovely. I’m the advisor, so I’m sure I’ll be seeing a lot of you. How are you finding Chicago? Settling in all right?”

“Yes, ma’am.”

“Ma’am! Please, call me Ms. B. Where are you from?”

“El Paso.”

“Ah. I’ve only been there once. EPMA is a lovely museum. Have you been to the Art Institute yet?”

“No, I haven’t.”

“We’ll be doing a field trip later in the year, but if you are a lover of art you must go. It’s one of the prides of Chicago.”

“Thanks, Ms. B, I will.”

"Now if you’ll excuse me, Dante, I have to prep for next period. See you in a few hours!”

Ms. B went over to her daughter Raija, who had been sitting off to herself drawing in a sketchpad for most of lunch, and gave her a quick side hug before disappearing into a supply closet. Since everyone else was getting packed up I ate the rest of my lunch quickly and consulted my schedule to see where I was headed next.

“You’re in sixth period drawing?” I looked up and saw it was Joseph who had asked me the question. Standing up instead of hunched over the desk I saw how truly long and lanky he was. He was about a foot taller than me.

I nodded up at him and tried to smile but had a hard time keeping eye contact.

“Cool. Me too.”

He flicked his lighter a few times in his right hand and then grinned a lopsided grin at me before heading out into the hallway right as the bell rang.

This was shaping up to be a much different first day of school than I had expected.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chapter 39: Letter 1

Dear Ari,

Okay, I think I’m falling in love-at-first-sight with Chicago. I know, I know, it’s only been two weeks since we moved...but the noise! the energy! the people! the pizza! (I’m sort of kidding, but not really. Deep dish pizza = a crazy good cheesy gooey mouth orgasm of decadent delight). Chicago’s so different from El Paso. Not better, but different. I wish I could send you a cassette tape of everything I’m hearing right now. There’s the clanking and sometimes ear-splitting screeching of the El train as it snakes along the track overhead; cabs blaring and honking in rush hour traffic; a street drummer going to town on a plastic bucket; snippets of conversation in a jumble of different languages as people pass by on their way home from work. There’s also a group of kids from my new school at a table near mine talking and laughing so loud they could be mistaken for urban hyenas escaped from the zoo. I think they’re doing it so everyone looks at them and wishes they were them and having as much fun as they’re having (or pretending to have). But I’m happy to be sitting by myself for a little while, taking everything in, writing to you. (Oh, I’m sitting at a coffee shop that has some outdoor tables that’s pretty close to my new school. I’m not friends with the loud obnoxious laughers, but I have made some new friends. Mostly goths and New Wavers. But I’ll tell you about that later).

Here’s another thing I like about downtown Chicago: the buildings! They’re so much taller here than in El Paso’s squat valley. It’s weird not having open sky though. But I love all the elegant old art deco buildings and how their fancy, intricate geometry pushes right up against grimy bodegas and newsstands and five-and-dimes and all night diners. I like the shine as well as the dirt and the grime. I even like the sort of rank, oily smell of the river. Is that weird?

I like people watching, especially on the El. If I’m brave enough I want to bring my sketchbook and secretly draw people. Not in a creepy way! Just so I can try to capture the kaleidoscope variety of people and faces and nationalities here. There are people from all over! It makes me feel like I can disappear, but in a good way. Like no one will bat an eye that I’m me, Dante, the odd duck Mexican teenager who’s bad at being Mexican. I can be anyone and no one. It’s sort of freeing.

I wrote this poem just now, it’s in a sort of new style I’m trying out:

traffic beats & city streets

feet & heels click slick cement

look up! the El is grinding, winding

eyes staring sirens blaring people wearing

their skin like it’s what they’re most comfortable in

Mexican sparrows Spanish staccatos

African rainbows Indian spices

black & brown & beige & pink & white

tight jeans taught muscles arms chests legs thighs

guys banging can drums bouncing hand balls

afros punks street soldiers skinheads skate boarders

bruised knees scrapes shouts break dancers

break it all down

Chicago’s own

welcome me to my new town

It’s okay if you don’t like the poem. It’s probably not very good. It’s just hard to describe how I feel being here, being surrounded by all this newness, all these different types of people, and being myself but not myself because I’m sort of anonymous, like I’m wearing a disguise or something, just observing, taking it all in.

Anyway, I’m babbling.

How was your first day of school? Were you nervous, scared, excited, bored? Did everyone ask about your crutches?

I made some friends the first day. I wasn’t expecting that. A girl named Clio sort of took me under her wing and introduced me to all her artsy friends. She dresses all in goth style (black clothes, black lipstick, crazy spiked up hair) and is really into Mary Shelley and a bunch of bands I've never heard of with names like Alien Sex Fiend and Christian Death. She writes amazing but super dark poetry and smokes clove cigarettes, which smelled surprisingly good. Have you ever smoked a clove cigarette? I kind of wanted to try it but chickened out. She and her group invited me out tonight to this place called Medusa’s that puts on all ages punk/rock/hardcore shows. I’ve never been to a club like that so I’m sort of curious but a little intimidated. I told them my parents had me on strict curfew (which isn't totally true) because I don't think I'm ready yet to dive into their whole scene. I think I'll go the next time I'm invited out though. (Side note: at first when Clio asked me, she told me everyone would meet up first at the “D’n’D”, which is her shorthand for Dunkin’ Donuts. At first I thought she meant Dungeons and Dragons, which led to me admitting to her that I used to play religiously every Friday night in middle school. But she thought it was cool, not weird or dorky. They're the least judgmental group I think I've ever met). Clio is cool. She’s sarcastic and puts on a tough front but she’s also sweet. (Does that remind you of anyone else we know??? Hmm?). I think you’d like her.

Are you doing anything fun this weekend?

I’ll write back again soon if I have anything new and interesting to report.

Your friend,

Dante

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chapter 38: Clio

First day of school, University of Chicago Laboratory School aka Lab aka U-High, 1987. (I couldn’t believe I was going to a school nicknamed U-High and I’d never even gotten close to taking a single puff of marijuana before. I felt like I was failing at basic teenager-ing).

U-High was an expensive fancy private school, but because of its affiliation with the university I got a 50% tuition discount for being a professor’s kid. A lot of the kids going there were professors’ kids too, which I wasn’t all too thrilled about at first. Yes, call me the world’s biggest hypocrite, but going into it I thought everyone would be exactly the same: rich overachievers hyper focused on 4.0 GPAs and perfect SAT scores and winning all the sports trophies and joining a zillion extracurricular activities just to make Ivy League colleges drool. And yeah, there were a lot of kids there exactly like that. But not everyone.

I was in Home Room, waiting for teacher to take attendance before the first class bell. The room buzzed with excited chatter laced with first day back jitters. Everyone seemed to be best friends already; or at least, it seemed clear that all the little social circles had already been well established years beforehand. I was doodling on the back of my class schedule, trying to look like I didn’t care that I obviously had no friends. Trying not to think of Ari too much.

“Pssst. Hey you. New guy.” Someone sitting behind me flicked my shoulder with a pencil, kind of hard.

I turned around and the boy behind me handed me a folded up piece of paper. He gestured vaguely to the back of the classroom and then went back to the conversation he’d been having with his friends.

Confused and a little nervous, I opened the note.

Hey Artist Boy, what’s your name? I’m Clio. You can sit back here with me if you want. (Or you can continue be an antisocial tortured artist if that’s your jam). (No pressure).

I looked in the direction the boy had pointed. A few rows back sat a girl who waved at me with a little smirk. She also appeared to be sitting by herself.

She didn’t look like anyone I’d met in El Paso and I tried not to stare too hard at her. Her face was super pale. Like, on purpose pale done with makeup. She looked like a porcelain doll, but with thick smudgy eyeliner and deep purple lips, almost black. She had a nose ring and an eyebrow ring and a lip ring and wore safety pins through her ears. She had on all black clothing with lots of chunky metallic chain jewelry. Her platinum blond hair was teased out in enormous feathery puffs. She was kind of scary looking, but also intriguing, and beautiful. I smiled back at her and her face lit up. I got up to move seats.

“Hey,” she said.

“Hey, I’m Dante. I’m new. Just moved from Texas.”

“I could tell.”

“That I’m from Texas? I’m not even wearing cowboy boots.”

She smiled. “No, I could tell you’re new.”

“That obvious?”

“It’s a small school. And most of us have known each other for ages. Some of our parents were even in, like, Lamaze class together back in the 70s.”

“Lamaze?”

“You know…Lamaze. Baby breathing?” When she saw my still totally confused expression, she did a series of rapid firing breaths and exaggerated grimaces like a woman about to go into labor while gripping the edge of her desk and her belly for support. We both laughed. I liked her laugh; it was giggly and twinkly, somewhat at odds with her intense punk look.

“What were you drawing before when I was spying on you?” she asked.

I showed her my doodles, which were really nothing special. Some birds and storm clouds and a desert landscape at night. Her eyes went wide.

She smacked my shoulder (in a friendly way). “Get out, Artist Boy, you’re really good! I was expecting, like, manga sex scenes or something. But this is quality. Want to join Plexus? That’s the Art and Lit Mag. I’m the editor this year."

“Um…”

“Please say yes.”

She fluttered her big doe/raccoon eyelashes at me.

"Um...sure?"

She grabbed my schedule and turned it over to compare it to hers.

“Looks like we have lunch together. Sweet! The Plexus crew always eats lunch in the art room in the C Wing. Go there instead of the cafeteria and I’ll introduce you. And after school we’re prob gonna go to Wax Trax. Have you been there yet?”

“Is that like…a wax museum?”

She shivered like she had the heebie-jeebies.

“Uch, wax museums give me the creeps. They’re the worst. Like, you just know all those wax figures come alive at night when no one’s around and have crazy wax orgies and then have a ton of weird creepy bastard wax babies." She shivered again. "But no. Wax Trax's the best record store in town. We all basically live there. I'm in love with one of the clerks but I don't think it's ever gonna happen, alas. What bands are you into? I like lots, not just punk and deathrock. Though Siouxsie and the Banshees is my fave right now."

“Um…I like The Beatles?”

Her eyes got big and she laughed, but not meanly. “Ok, I’m definitely adopting you, Artist Boy. You're the most adorable. Consider me your Chicago Cultural Ambassador.”

The teacher finally shushed everyone for announcements and attendance and Clio and I kept passing our note back and forth. (I felt like a major rebel). When the bell rang we collected our things. "Don’t forget. Art room for lunch. Promise?” she said and held out her pinky. I pinky promised with her and she pointed me in the direction of my first class.

And that’s basically how I ended up making friends with U-High’s one and only goth crew on the first day at my new school.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chapter 37: Not The End

During the last few days before we left for Chicago, my room was almost as blank and empty as Ari’s. My bed was still there, along with my empty bookshelves and desk and comfy reading chair, but mostly everything else that made the room mine had been boxed up in storage or packed up to take with us. It was kind of weird, but kind of peaceful too. I sort of understood why Ari liked his minimalist (i.e. nonexistent) interior decorating strategy. My head felt clearer those last few days than it had since the accident. A grad student was going to be living in my room next year and I made sure to leave a little note for them warning that birds liked to hang out on the window sill but it wasn’t a big deal – they were completely harmless but sometimes a little noisy.

The day before we left, my parents and I went over to Ari’s for dinner. I know that our parents had all met each other before because of the accident, but this was the first time we were all together purely socially, like one big family. Even though the occasion was sad, I wasn’t sad that night, not really. I liked how well our parents got along. My dad and Ari’s dad hit it off like gangbusters and spent the whole night drinking beer (blech) and talking politics. Our moms cooked together and talked in Spanish.

After dinner, Ari and I hung out on the porch. We weren’t talking much but I was okay with it. It was peaceful, like my blank room. I took mental snapshots of all of us together in my head to remember for forever.

“Your sketch pad is under my bed. Will you get it for me?” Ari said, out of nowhere.

It took me by surprise. I’d almost forgotten about the sketch pad I’d given him in the hospital. I had a flashback to how he looked that day hooked up to his hospital bed, with his double casts and banged up face and cloudy, pain-filled eyes. My stomach clenched at the memory. He was so much better now, I reassured myself. His arm was healed, he had crutches and not a wheelchair, he was going to be fine. But it didn’t make the queasy feeling in my stomach go away.

I almost told him I didn’t want to get the sketch pad. Showing people my artwork still embarrassed me most of the time. But I had given the sketchbook to him as a gift and it would be weird of me to refuse to look at it now with him.

I nodded and went inside to his room to get it. It was right under the bed, like he said it would be. His journal was under the bed, too. When I saw it, my heart slammed into my chest. I picked up his journal, just held it in my hands for a few seconds. It had a soft leather cover, smooth to the touch. Almost without intending to, I opened it up to a random page. My eyes quickly scanned the words:

I don’t like being fifteen.

I didn’t like being fourteen.

I didn’t like being thirteen.

I didn’t like being twelve.

I didn’t like being eleven.

Ten was good. I liked being ten. I don’t know why but I had a very good year when I was in fifth grade.

The fifth grade was very good. Mrs. Pendragon was a great teacher and for some reason, everyone seemed to like me. A good year. An excellent year. Fifth grade. But now, at fifteen, well, things are a little awkward. My voice is doing funny things and I keep running into things. My mom says my reflexes are trying to keep up with the fact that I’m growing so much.

I don’t care much for this growing thing.

My body’s doing things I can’t control and I just don’t like it.

I snapped his journal shut without reading any more and tucked it hastily back under the bed. I felt like a criminal. My heart was still beating so fast. I shouldn’t have just done that. I went to the bathroom and put some cool water on my face. It’s not that I didn’t desperately want to know what was inside Ari’s head. I did more than anything. I wanted to know if he still hated being fifteen and what other changes his body had gone through that he would never ever talk to me about. I wanted to know if he’d truly forgiven me, if he thought we’d be friends when I came back, if there was an inkling of a chance he liked me in the same way as I liked him. If he loved me, too. But it wasn't right, reading his journal without him knowing. I couldn’t betray his confidence like that ever again. His thoughts and trust had to be freely given, like I’d given him my sketchbook.

After my cheeks had cooled down, I went back outside to the porch and handed him my sketchbook. I was ashamed to look him in the eye.

“I have a confession to make,” he said.

“What?” I asked. My heart was still going wildly fast. I had no idea what he might say. Had he read my journal, too?

“I haven’t looked at it.”

Oh. I didn’t know what to say. My feelings were a little hurt that he’d never bothered to look at what I’d given him. But considering what I’d just done, I really had no ground to stand on for what constitutes being a good friend or not.

“Can we look at them together?” he said.

I didn't say yes, but I didn't say no, either. I was caught in some sort of silent limbo. He opened the sketchbook. The first drawing was a self-portrait of me reading, which I thought was a bit pretentious in hindsight. The next one was of my dad reading, which was not so bad. Then there was another self-portrait, more close up, just of my face.

“You look sad in this one.”

“Maybe I was sad that day.”

I remembered the day I drew that one. It was right after my parents had told me we’d probably be moving to Chicago.

“Are you sad now?”

Yes. Yes and no. Yes, I was sad to be leaving. But meeting and becoming friends with Ari this summer made me happier than I’d been in the longest time. I didn’t answer his question and we kept flipping through the book. We came to the sketches I’d done of Ari in his room, the same day I’d given him the drawing of his rocking chair. There were five or six sketches of him sitting on his bed, reading. Some close ups of his hands and his eyes. One of him sleeping. My face flushed as Ari traced his fingers over the page. I was a little embarrassed at how seriously he was studying each and every picture. I was glad he couldn’t peer into my head and know what I’d been thinking while I was drawing him. It was too embarrassing. But I was honored and a little humbled, too, to share this part of me with him.

“They’re honest,” Ari said.

“Honest?”

“Honest and true. You’re going to be a great artist someday.”

“Someday,” I said. I thought I might cry, but I didn’t. I cleared my throat and said, “Listen, you don’t have to keep the sketchbook.”

“You gave it to me. It’s mine.”

He looked at me and the tension I’d felt since I snuck a peak in his journal finally subsided. We looked through the remaining sketches and sat on the porch together as night fell and the sky changed from blue to dusty pink to orange. The air smelled like a future rainstorm.

My parents came outside and told us it was time to head out, we had a big day tomorrow. My dad gave Ari a kiss on the cheek and my mom touched his chin in that inscrutable way she has.

I hugged Ari.

He hugged me back.

It was a little awkward with his crutches, but I don’t think either of us cared.

I touched the back of his neck, his hair. It was as soft as I always thought it would be.

“See you in a few months,” I said into his neck.

“Yeah,” he said.

“I’ll write,” I said.

I didn’t cry, not then. I didn’t cry until very late that night when I was alone in my empty room listening to the wild rain beat down. In that moment, holding my best friend close to me, feeling our bodies aligned, breathing him in and breathing in the smell of my last summer night in El Paso, I was the happiest boy in the universe. Because I knew I’d be back here again, with Ari. I knew this wasn’t the end of us.

#aaddtsotu#ari and dante fic#please excuse the long hiatus life got in the way!#hoping to get back to a regular posting routine!

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chapter 36: Swimming and You

A few days after I got my cast off, Ari got his arm cast off, too. I went over to his house that evening and we sat on his front porch. He stretched out his arm that had been broken and I stretched out mine.

“All better,” I said. “When something gets broken, it can be fixed.” I bent and stretched out my arm again, relishing in the simple freedom of movement. Now that the cast was off, my body was already forgetting what all the itchiness and constriction had felt like, how unbearable it had felt at first. “Good as new.”

“Maybe not good as new,” he said. “But good anyway.”

I thought about that phrase ‘good as new’. Ari was right; our arms would never be exactly the same as they were before we broke them. They’d never be perfectly new. But who says new things are the best things? The standard to be judged against? Most of my favorite things—my mom’s record player, the photos of my parents from college, the books that I’d dog-eared and highlighted and scribbled notes in all over the margins, my threadbare jeans with holey knees that Ari made fun of—were old and well worn. Of course there’s the thrill of getting something sparkly and new like my telescope or the excitement of cracking open an unfilled sketchbook or journal, when the anticipation of creation, the unsullied blankness of the pages, is part of the allure. But things are useless until you take the care to work them in, to make them yours, to create or discover something with them. I guess all relationships have that allure of newness at first, too. The thrill of meeting someone for the first time, seeing if you have that spark of connection, that zing that makes you think, ‘This is someone I want to get to know, to reveal myself to’. But how can you really know someone if the bad stuff—the stuff that scuffs and scrapes you up, that wears down the shine—doesn’t happen too? I think ‘good as old’ is actually more fitting than ‘good as new’ when it comes to the people you love the most.

And with other things, like swimming for example, you’re not very good when you’re new at it. It takes time, practice and patience to build muscle and endurance and to reach the level where moving through the water feels natural, not like you’re competing against it. To get to that level of quietness and focus inside even when your body is pulling against the full weight of water. To feel like you can breathe underwater even though that’s impossible.

“I went swimming today,” I said.

“How was it?”

“I love swimming.”

“I know,” he said.

“I love swimming,” I said again. I knew what else I wanted to say to him right then. I saw the words hovering over my head like a thought bubble in a comic. I took a breath but the words didn’t come out. The pit had dropped out of stomach in a way I imagine a sky-diver feels like right before they make the jump. Trust the free fall, I told myself. Trust you’ll land safely on the ground.

“I love swimming—and you.”

Ari didn’t say anything.

“Swimming and you, Ari. Those are the things I love the most.”

“You shouldn’t say that,” he said.

“It’s true.”

“I didn’t say it wasn’t true. I just said you shouldn’t say it.”

“Why not?”

“Dante, I don’t—“

“You don’t have to say anything. I know that we’re different. We’re not the same.”

He nodded his head but refused to meet my eyes. I felt a stinging tightness in my throat and my eyes itched but I needed to ask him the one thing that I’d been the most afraid of.

“Do you hate me?”

I’d gotten the feeling over the last few weeks that Ari resented me coming over and reading to him every day, resented me trying to draw him out of his shell when he really wanted to be left alone. Like being friends with me was too big of a burden and was keeping him from healing, keeping him hurt. If that was true, I didn’t know what I’d do besides leave his front porch and never come back.

“No, I don’t hate you, Dante.”

I released a long breath I didn’t know I’d been holding. We sat in silence for a while. Ari and I were on shaky ground, but not shattered.

“Will we be friends? When I come back from Chicago?”

“Yes,” he said.

“Really?”

“Yes.”

“Do you promise?”

“I promise.”

Relief washed over me. I smiled and he smiled back. I didn’t feel like crying anymore.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chapter 35: Unsent Letter

Dear Ari,

I’m not going to send this letter. It’s for my eyes only. Oscar (my counselor) was the one who encouraged me to write this. He thinks it’ll help me finally move on from the accident and be able to get a fresh start when we leave El Paso. He asked me, “If you could tell Ari anything at all, without worrying about what he might say or how he’d react, what would it be?”

I’d tell you how amazing I think it is that we found each other. It’s crazy to me that I only met you two and half months ago. It seems like I’ve known you forever. Why do you think it is that you can be around some people for years and never really know them and for other people it just takes a few hours and—bam!—you know they get you—that they see you, really see you—and vice versa. Is that what adults call “having chemistry?” Is it somehow related to pheromones? Is there a friend version of that phenomenon, where with some people you get immediate friend sparks—Bunsen burners exploding, gaskets blown!—and with other people it's just dud central? Like, with my cousins. We visit with them on the holidays every year but it’s like a blank slate each time. Tabula rasa of anything interesting we’ve ever said to each other. We must resort to talking about sports I care nothing about or which distant relatives are popping out babies or how good the food we’re all currently masticating is. Blah city. But with you, we could talk for hours about the stupidest things and I’d love every minute of it. I want to know every little thing there is to know about you and I want you to know me, too. I want us to know each other so well that we could fit into all the little secret spaces of each other’s souls.

Yeah, okay, that was corny. And I’d never say that to you out loud. But I guess that’s the whole purpose of this letter. To say the unsayable.

I’d tell you again that I’m sorry about the accident. That you got hurt. And now we’re both changed because of it.

I’d tell you that there’s nothing about you that I don’t like. I like your sullen, introspective moods just as much as your happy ones. I like “debating” with you (okay, arguing) just as much as when we agree on things. I like when you make a deadpan joke and don’t crack a smile until the last possible second, like you’re playing a game of chicken with yourself. I like the way your face settles into concentration when I’m reading to you. Even with your eyes closed, it’s like I can tell what you think about a certain passage just by a quirk of your eyebrows, the tiniest curve of your mouth. I like when your hair is greasy and you’re a little smelly and you haven’t shaved just as much as when you’re fresh and soft and clean. I like looking at your face a lot. That’s not something I can actually tell you, is it? That I like every part of you because they make you who you are, make you the boy I love.

Ok, now I’m verging into Hallmark puke territory again. But sometimes that sort of thing is okay. In small doses. In love letters that will never be sent.

I’d tell you: don’t be afraid of becoming the person you were meant to be. (And then I’d try to take that advice myself).

I’d say I love you right out loud and I’ll miss you like hell when I’m gone.

That wasn’t so wrong or scary to admit, was it? It made me feel good writing it, acknowledging it. The truth feels good to let out of its cage, soaring out into the open sky where it belongs.

Love,

Dante

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chapter 34: Self-Portrait at the End of Summer

Since the accident, my mom had been on a mission to keep me as busy as humanly possible. I think she thought it would keep me from slipping into another low spell if she kept me perpetually occupied. I have to admit her strategy actually kind of worked. I’d go over to Ari’s in the morning then come home and help my dad with the garden. Once a week I’d go to counseling with Oscar. My mom also decided the move was the perfect opportunity to give our house an organizational overhaul, so I helped her decide which things we’d take with us to Chicago, what we could keep for the grad student subletters, what we could give away to Goodwill and what we’d need to put in attic storage. We had shoeboxes full of photos that she’d never had a chance to put into albums so that was a big project we did together. I especially liked looking through the photos from when my parents were in college. I liked seeing their progression from mysterious almost-strangers to the people they are today. In some of them my dad is barely recognizable with his shaggy hair, ill-conceived facial hair and hippy dippy clothes. My mom’s style doesn’t change as much over the years. She’s younger yes, with less gray hair, but the same fierce love and beauty I see in her now shines through in all the photos of her and my dad together. She’s an old soul, my mom.

She also gave me the assignment of planning out our road trip from El Paso to Chicago, so I spent time at the library doing research about where I might want to visit on our pit stops. She signed my Dad and I up for Sunday shifts at the local food bank and made us all take weekly hikes in the desert so I’d stay in shape while my cast was still on and I couldn’t swim. Like I said, she was on a mission.

Despite all this I still had plenty of free afternoons where I didn’t have anything pressing to do and I’d lay in the hammock in our back yard for hours. I’d usually bring a book out with me but ended up looking up at the sky or drifting off or getting lost in daydreaming. I liked it out there in the shade, rocking gently in the breeze. It made me feel suspended in time, like the summer would last forever. But before I knew it four weeks had passed and it was time for my cast to come off and in a week we’d be leaving El Paso. I wasn’t sure if I’d ever call El Paso home again. And if we did come back, I wasn’t sure Ari would still be my friend when we returned. I didn’t like to think about that.

The day I got my cast off, I went swimming. My arm was sore and my muscles were weaker so I took it slow. But being in the water again felt right. Like coming home.

After I got back from the pool I drew a self-portrait and wrote in my journal, luxuriating in holding a pencil confidently again in my right hand. This is what I wrote:

This is me, Dante Quintana.

This is the me I am today.

Do I look like the same person I was

before the hailstorm came?

Before the sirens and the near escape?

I’m the same height and weight.

My eyes are still creek brown,

my hair is still inky black.

My face is no longer splattered with purple and blue.

My bones are healed and sealed.

My lips are unsplit pink.

Then how come I feel different?

If I’m not the same me the mirror saw six weeks ago,

whose face is looking back?

Who am I trying to recreate with charcoal and paint,

with lines and shades?

What am I trying to erase if not my secrets and shame?

I don’t want to lie but I’m still terrified

of becoming the me I see when I close my eyes and dream.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chapter 33: The Gift

I ended up going back once a week to talk with Oscar until the end of summer. We talked about a lot of things: school, my parents, not feeling like I fit in with the rest of my family, the upcoming move to Chicago, my interest in art and astronomy, and my friendship with Ari. We talked a lot about Ari. He would probably have been embarrassed by the amount I talked about him to Oscar, but I enjoyed it. It made me feel connected to Ari even when his distant and sad moods continued through July and August.

I never told Oscar that I loved Ari in so many words. I was too embarrassed and afraid to say it out loud, even to someone I ended up trusting as much as Oscar. But Oscar and I talked about what it meant to love someone, in general terms. How people express it differently. Knowing that talking about feelings had as much appeal to Ari as eating a plate of slugs, I wondered if there was a way I could let him know how much he meant to me in actions not words. I visited him every day, but it still didn’t seem like enough. Oscar wondered if there was anything I could do to help Ari’s mom with looking after him. I wasn’t sure but I decided to talk with Ari’s mom about it.

She was at her normal place at the kitchen table when I popped my head in after I’d left Ari in his room one day.

“Hi Mrs. Mendoza. Do you have a second?”

“Of course. Everything ok with Ari?”

“Yeah, we were just reading and he got a little tired so I’m gonna head home. I was just wondering…um…well, do you need help with anything? With Ari, I mean? I’d like to help if I can.”

“Well, I think you already help him a lot, Dante. I know Ari can be a bit…monosyllabic…but you must know how much you coming over and visiting him means to him. You’re like his rock, you know?”

I wasn’t sure why my cheeks felt so hot all of a sudden.

“I don’t know about all that,” I hedged. “I just meant…is there anything I can do to help you help Ari? You’ve probably got lots of prep work to get ready for the school year to start and now that he’s stuck in his casts I’m sure it’s a lot of extra work. I just mean, I feel bad about the accident and I wish there was more I could do to help him. And you.”

“Well, I get him in and out of his wheelchair from bed and take him to his doctors appointments and help with some bathroom logistics and getting dressed, but none of that’s really appropriate for you to do. I also give him a sponge bath and shave every morning.”

I remembered one of the dreams I’d had while I was sick with the flu—where I’d helped Ari into the pool while he was still in his hospital gown and I’d cracked his casts apart like eggshells and washed him clean. I wasn’t sure Ari actually would let me wash him, but it was something I knew I wanted to try.

“Do you think that’s something I could help with? Would Ari mind? How do you give him a sponge bath exactly?” I was struck with an image of Ari in the bathtub that made my cheeks burn even redder. “He’s not naked, right?”

She laughed, but not meanly. Probably because she saw how terrified I probably looked. “No, we have a whole system. He wears his trunks or shorts, don’t worry. He usually stays in his wheelchair but the hospital did give us a little stool for the bathtub we use sometimes. I fill up a bucket with warm soapy water and use a washcloth to clean him and another one to dry him off. Sort of like doing the dishes,” she chuckled.

“And shaving? You’re not afraid of nicking him?”

“He’s gotten good at staying still.”

“So you think I could do all that?”

“I don’t see why not.”

“I’d like to help you. Is tomorrow ok?”

“Sure.”

“Okay, thanks Mrs. Mendoza.”

“See you tomorrow, Dante.”

The next morning I got to Ari’s house right after breakfast. I was still unsure how Ari would react when I told him what I wanted to do. But I was determined to try.

“So, I was thinking this morning I’d help with your sponge bath. Is it okay?” I asked.

“Well, it’s kind of my mom’s job,” he said. His voice sort of sounded like he'd just swallowed a bug.

“She said it was okay.”

“You asked her?”

“Yeah.”

“Oh,” he said. “Still, it’s really her job.”

“Your dad? He never bathed you?”

“No.”

“Shaved you?”

“No. I don’t want him to.”

“Why not?”

“I just don’t.”

I wanted to tell him so many things then. That it made me feel good making sure he was taken care of and happy. That I wouldn’t mind if it was my job to look after him. That it would be an honor to have him trust me again, a gift. Instead I said, “I won’t hurt you. Let me.”

A moment passed in silence and then Ari said okay. I could hardly believe it actually. My heart started firing off in quick hummingbird bursts but I tried to stay really calm. I rolled him into the bathroom and helped him out of his tshirt and out his special sweatpants that had a zipper all the way up the sides. He was just in his boxers and asked for a towel to put over his lap and leg casts.

I’d seen Ari in his bathing suit without his shirt on plenty of times at the pool. But it was different now that we were alone in the small bathroom. We didn’t talk or make jokes like we normally did as I filled up the bucket with warm water and enough body wash to make the water sudsy like a bubble bath. I dipped the cloth in the water and Ari shut his eyes. I started washing his shoulders, rubbing the soapy washcloth in slow smooth circles, being careful not to be too rough or scratchy with the towel. I watched the pulse point on his neck throb. It seemed at odds with the total stillness of his body and his long steady breaths. I washed the front of his chest and tried not to think about anything but being as gentle and careful as I could with him. I tried not to think about what my lips would feel if I kissed him on all the places the washcloth touched. I knew I shouldn’t thinking about kissing him right then, but I couldn’t help it. A strange tender ache had settled over me, reaching all the way from my chest to the base of my spine. I don’t know why, but tears fell down my face. I felt something close to what I imagined my parents felt when they were worried I’d been seriously hurt in the accident; like I wanted to protect Ari from getting hurt ever again even though I knew that was impossible. I kept washing him and let the tears silently flow, trying hard not to sniffle and cause him to open his eyes. I covered his chin in shaving cream and gently gently slid the razor down his chin and over his upper lip. I loved the shape of his lips and how pink they were next to the white shaving cream.

After I was done washing and shaving him, I patted him down with a fluffy dry towel and imagined that the towel was my arms, holding and hugging him tight, engulfing him in softness and warmth.

I’m glad Ari kept his eyes closed the whole time. Not because I was ashamed of crying, but more because I could drink him in and memorize all the details of his face and body that I wanted to save for when we were separated. He was giving me a gift and didn't even know he was, which made me even sadder in a way, but still grateful.

When I finished up and Ari opened his eyes, I knew he saw that I'd been crying. But he didn't say anything about it or poke fun of me for it, which was another small gift in its way. But he did have a lost and distant look in his eyes, like he was the hurt bird I'd seen in the road the day of the accident. I couldn't cradle or protect him, though, as much as I wanted to. I knew without either of us mentioning it that this was probably the only time he'd let me wash him like this.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

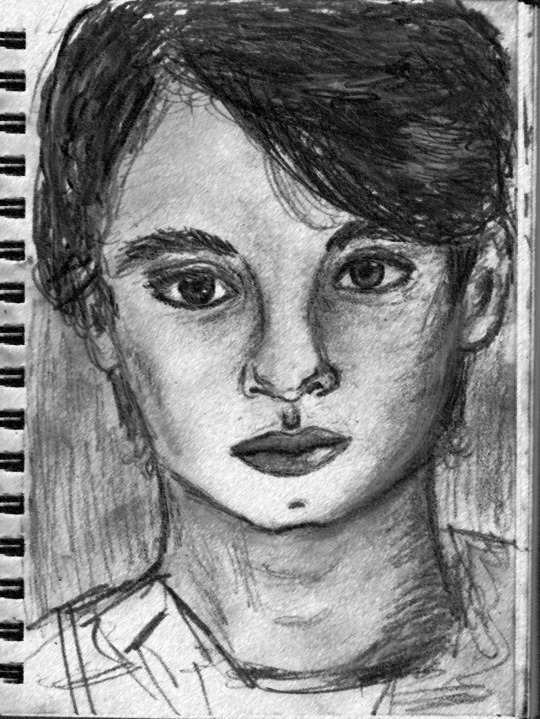

Chapter 32: Rainbow Bird (charcoal and colored pencil, drawn by left hand)

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chapter 31: Oscar Ramirez

I got over the flu but it left behind a restless drawn-tight feeling inside me that I couldn’t shake. I went to visit Ari every day but other than that I didn’t leave my room much. My mom finally insisted on scheduling an appointment for me to see one of her counselor colleagues, Oscar Ramirez. I didn’t fight her too hard on it. I knew it was probably a good idea to talk someone. Oscar worked for the same shelter/halfway house my mom did in addition to having an off-site office. I’d met a few of her colleagues before but never Oscar, which made the idea of talking to him easier somehow.

Ari had been released from the hospital for about a week and a half by the time I went to talk to Oscar for the first time. I’d been going over to Ari’s house every day to visit him. Sometimes we’d go for “walk and rolls” around the neighborhood but mostly we hung out in his room. I decided to read The Sun Also Rises aloud to him (mostly because Hemingway’s sparse, terse writing style reminded me of Ari, but I didn’t tell him that). I read a chapter or two each visit and we’d talk about it after. One time we talked about where we’d go if we decided to become dissolute ex-patriots like the characters in the novel and travel the world together. I wanted to go to Paris; Ari wanted to go to Iceland or Norway. When I asked him why, he said he was sick of the Texas heat and wanted to see the Northern Lights.

“I bet there’s no light pollution up there,” he said.

“Sure, no light pollution, but the winter’s colder than a witch’s tit.”

He snorted. “I wouldn’t mind the cold.”

“How do you know? You’ve lived in Texas your whole life.”

“It snows here sometimes, you know. Like two Christmases ago.”

“I know, but El Paso winter is nothing like up there. We’d need to bring special snowsuits and camping gear or risk dying of hypothermia.”

“It’d be worth it though. To go somewhere so remote and cold and quiet.”

“Sounds like you really want to go on vacation to The Fortress of Solitude.”

“Hey, don’t knock The Fortress. A man needs a place where he can be alone and think.”

“And freeze his face and nuts off in the process.”

“That’s just the price you pay to stop everyone being all up in your business all the time. And anyway, Superman is impervious to frost bite. And don’t talk about Superman’s nuts. That’s sacrilegious.”

“I wasn’t talking about Superman’s nuts specifically. Just frozen nuts in general.”

“Okay okay enough with the nuts talk. Jesus.”

“What? They’re just a body part. No weirder than pinky toes or noses.”

“Yeah, okay, whatever. Hey I’m pretty wiped…so…I might take a nap or something.”

Ari’s face was flushed he looked sort of agitated so I cut my visit short after that. I could tell something was off between us but I didn’t try to press him. Sometimes when I went to visit I wasn’t even sure if he wanted me there. I figured he had every reason to be resentful of me. It was my fault he was stuck at home for the rest of the summer, at the mercy of his painfully itchy and useless legs. I was afraid more than anything that he’d want to stop being friends with me if I needled him too much or asked him what was wrong. So it was easier to talk about books or imaginary plans to travel the world together than what I actually wanted to talk about, which was how badly I was going to miss him when we moved and how sorry I still was about the accident.

When the time came for my appointment with the counselor, I was nervous even though I knew seeking counseling was a totally normal thing to do. Nothing to be ashamed of.

“Do I have to lay down on a couch?” I asked my mom on the car ride over.

She smiled. “Of course not. That’s the sort of thing you really only see in movies nowadays.”

“Good, because that part always seemed a little weird. Do I have to analyze my dreams?”

“Only if you want to.”

“What if I run out of things to say and we just stare at each other in awkward silence the whole time?”

“You’ve never had a particular problem with maintaining conversation, Dante. You can talk to him about whatever you want. Or not talk. No pressure.”

What I really wanted to ask her was if she thought the accident had messed me up somehow, or worse, messed Ari up, and that’s the real reason she wanted me to talk to a counselor. Not physically messed us up. But if I’d caused something to get broken inside us. I had no issue with the field of psychiatry in general, seeing as it was my mother’s profession, but I didn’t like the idea of a stranger realizing there was something wrong with me that needed fixing.

Oscar had an office in the El Paso Child and Teen Guidance Center, which was located in a shopping center. That sort of surprised me. I’m not sure what I expected, but it wasn’t the totally mundane looking storefront hiding in plain sight next to a hair salon, pet store and a travel agency. Oscar greeted us at the reception desk, where he kissed my mom on the cheek and shook my hand.

Oscar was around my parents’ age. He was on the stocky side, but not fat or anything. He was the type of solid build that you could describe as equally fitting for a linebacker and a big teddy bear. He had a round, friendly face and close cut salt-and-pepper black hair that didn’t do much to make his appearance less boyish and wholesome. He had a firm handshake and big hands.

“Dante, it’s a pleasure to meet you. Your mom has told me a lot about you.”

“Thanks, you too. I mean, nice to meet you, too.”

After my mom checked me in and filled out some paperwork, she left me with Oscar and told me she’d be waiting for me in the reception area.

Oscar’s office was bright and decorated with colorful furniture, throw rugs and artwork, which also surprised me. In my mind I’d pictured something much more stuffy and clinical. To one side of the room was a small couch and an armchair, both plush and comfy looking; between them was a coffee table with a box of Kleenex on it, which I was determined I would not have to use come hell or high water. On the other side of the room was a kid-sized table and chairs plus art supplies and toy boxes, set up like a mini preschool. Seeing the kid stuff made me feel strange. A little sad for the kids who needed to come in here. The office also had a desk, several bookshelves, and a beverage station. Overall it felt more like a living room than an office.

Oscar gestured toward the couch. “Please, take a seat. Make yourself comfortable. Do you want some water? Tea?”

“I’m okay.”

Oscar sat down in the armchair across from me. “So, Dante. Before we get started, I just wanted to let you know that even though your mother and I are colleagues and she let me know a little bit about why she wanted you to come see me today, I want you to feel like this is a safe space to share anything that’s on your mind with the understanding that I take your trust and confidentiality seriously.”

“Even though I’m a minor and you’re legally allowed to tell my parents what we discuss?” I asked. I’d done my research about confidentiality ahead of time. More than the accident I wanted to talk about what it meant that I loved my best friend who was a boy, but I’d decided already to keep that part of me sealed in the vault no matter what. I couldn’t be 100% sure he wouldn’t tell my parents about that.

Oscar smiled. “You are definitely Soledad’s son. Yes, you’re absolutely correct. Even though you’re a minor I would breach confidentiality only if I was worried for your personal safety or the safety of others or in the rare instance that my notes were subpoenaed by a court order.”

“Wow, that would be pretty badass.”

Oscar raised an eyebrow but was still grinning. “Let’s hope it doesn’t come to that.”

“Sure, yeah. I was just joking. Discussion of client confidentiality protocol: check.”

It was a relief to hear him say he wasn’t going to tell my parents everything we talked about, but I still wasn’t quite ready to dive right into the accident.

“I like your office,” I said, stalling. I pointed to the kids’ area. “Do you work with a lot of children?”

“A fair number.”

“Do you do art therapy with them?”

“Sometimes. It depends on the child.”

“I’ve read all about the field of art therapy. I think it’s fascinating. If I don’t become a professional artist I might become an art therapist.”

“Would you like to do any drawing right now? We could start with some art exercises if you’re not in the mood to talk at the moment.”

“No, that’s okay. It’s hard for me to draw because of my broken arm. I’m a right-y. But thanks for offering.”

“So you’re okay to talk?”

I nodded.

“I’m glad. So, I understand from your mother that you and a friend of yours were involved in a car accident about three weeks ago and she’s concerned you haven’t been quite yourself since. That you’ve been having nightmares and seem much more withdrawn than usual. Do you want to talk about the accident? Or about what’s been on your mind?”

“So she already told you what happened?”

“Briefly. But I’d like to hear it from you, if you feel comfortable talking about it.”

“Well, it’d been raining and I went out into the street and didn’t see a car coming.” For some reason I didn’t want to tell him about the injured bird I’d seen. “Ari pushed me out of the way of the car and broke both his legs and his arm. He could have died but he didn’t.”

“Ari is your friend?”

“Yeah, my best friend.”

“How is he handling everything?”

“Um. Ok. I dunno. He can be kind of hard to read sometimes. They recently let him out of the hospital. He’s stuck in casts for the rest of the summer because of me.”

“And how have you felt since the accident?”

“I think my mom is worried that I’m showing signs of anxiety, depression and PTSD and that’s why they want me to talk to you. But I don’t have PTSD.”

“No?”

“No. I looked it up in the DSM-IV.” I ticked each symptom off with my fingers. “I’m not having recurring flashbacks or panic attacks. I’m not avoiding cars or the street. I’m not having angry outbursts. Well, I’m still kind of pissed at my parents about deciding to move to Chicago but that’s a different thing. Yeah, my dreams have been a little weird and I’m not sleeping great but that’s because my arm cast is so annoying. So I think we can safely say I don’t have PTSD. Possibly a little low-level anxiety. But I do deep breaths if I start feeling weird.”

“I don’t want to rule anything out just yet, but I’m happy to hear you’re listening to your body and your emotions. What do you mean when you say you start feeling weird?”

“I guess…sad. Stomach crampy. Frustrated. I think I’m worried about Ari. About how he’s recovering. About not being able to help him when we move.”

“It sounds to me like you might blame yourself for what happened to Ari.”

“Well, yeah, because it was my fault.”

“Who said it was your fault?”

“No one said it was my fault. But it obviously was.”

“Why do you feel that way?”

“It’s not feelings, it’s the facts. I went out to the street, I wasn’t paying attention and Ari got hurt because I was stupid and off in my own little world instead of paying attention to the road. And the thing about Ari is, he doesn’t like it when I’m upset, so he only let me apologize once and then he said we’re not allowed to talk about the accident anymore. He has some kind of stoic boy code about it. He wants to pretend it never happened.”

“Is that what you want?”

“Well, I don’t think we should, you know, dwell on it or anything. But I want him to know how sorry I am that I almost got him killed and ruined the rest of his summer.”

“Did Ari say anything like that to you? That you ruined his summer?”

“No. But he’s not big on talking anyway. But, like I said before, it’s a fact. Now he’s stuck in a wheelchair until his legs heal and he can’t do anything except hang around his house and read books and I know he’s pissed about it even if he won’t say anything.”

“Has he ever expressed anger or regret about what he did? That he saved your life?”

“No. Nothing like that. He’s just been moody and sullen. I mean, he’s been in a lot of pain so I don’t blame him for being crabby. I just don’t want him to hate me.”

“Why do you think he would hate you? It seems to me to be quite the opposite, that he cares about you very much. Do you want to tell me about him? How did you two become friends?”

“We met at the pool. I offered to give him swimming lessons. Because he didn’t know how to swim properly.”

“You like to swim?”

“Almost more than anything. Well, I like swimming, reading, drawing, stargazing and hanging out with Ari pretty much equally.” I lifted my cast arm and pulled a face. “Now my life is pretty much limited to reading and hanging out with Ari and teaching myself to become ambidextrous. Not that I’m complaining. I mean, I’m lucky to be alive. I know it’s babyish but I miss swimming with him. I wish I could retcon the whole day of the accident.”

“Retcon?”

“Oh that’s a comic book thing. Basically when the writers change things retroactively in a story to make up for continuity errors. Sort of like a big do-over. Usually that sort of thing bugs the heck out of me because it seems so lazy. But I get the appeal now. Like you have God’s big eraser.”

“It’s natural to wish you could change the past so easily. But it’s equally important to learn how to move forward. And to not beat yourself up over something you can’t change.”

I shrugged and picked at my cast. “I just keep thinking that if it had been Ari in the middle of the road, I wouldn’t have been able to save him. I wouldn’t have been fast or strong enough. He was like Superman, the way he dove at me and pushed me out of the way.”

“Why do you think you wouldn’t have been able to help him if your roles were reversed?”

“Because when I saw the car coming, I just froze.”

“That could have been your body experiencing a fight or flight reaction. And also Ari saw the car coming whereas you did not, yes? So he had more time to think and react.”

“But still, I don’t think I could ever be as brave as he was.”

“You may be underestimating yourself and your strength. It sounds to me like you’re beating yourself up about a theoretical past as well as construing what actually happened to place all the blame on yourself. Just imagine what the people driving the car must have felt like. They most likely felt guilt as well. But motor accidents happen so quickly, in a blink of an eye, that it’s not helpful to play the blame game after the fact, particularly if it’s determined that the driver wasn’t under the influence of drugs or alcohol and the accident was just that: an accident. I would advise you to try not to blame yourself for the actions of others. And if that’s difficult, you may want to ask yourself, what am I getting out of continuing to blame myself for something that was out of my control?”

I didn’t quite know what to say to that.

He must have seen my confusion so he rephrased his question. “In other words, are you holding onto feelings of guilt and shame because you don’t think you’re worthy of having a friend who cares about you enough to put his own life in danger to save yours?”

I didn’t think I was worthy of it. But thinking about that made me start to feel like I might cry, which I had been determined not to do, so I clamped down and said nothing for awhile.

After a bit of silence Oscar said, “You know, I never read comics but my daughter loves them.”

“Really? Which ones? Betty and Veronica?”

“Actually The X-Men is her favorite. She loves all the Saturday morning cartoons based on comics, too.”

“How old is she?”

“Twelve.”

“And she doesn’t think X-Men is too scary?”

“Well, she’s always been a tough little cookie. Never was into any of the princess stuff. Except She-Ra Princess of Power. She adores She-Ra.”

“She-Ra is pretty rad.”

“Do you have a favorite comic?”

“Ari teases me about it, but I really like Archie. He thinks they’re lame. Which, sure, yeah, they can be pretty cheesy. But I don’t like the really dark comics.”

“There’s nothing wrong with that. There’s no rule that says you have to like all the same things your friends do.”

“Believe me I know that. I know I’m a little weird.”

“What makes you say that?”

“It’s not a secret or anything. Ari’s the first guy I’ve met my age who really gets me. I’ve never really had a best friend like him before. Not since we moved to El Paso anyway. I had a best friend in California but that was already years ago. We hardly see each other or write letters anymore.”

“And you’re worried that the accident and the move to Chicago will have a negative impact on your friendship with Ari? That you’ll lose touch and stop being friends? And you blame yourself for this future you see happening?”

I nodded, hoping to dislodge the traitorous lump that was forming in my throat.

“You’ve told me Ari hasn’t expressed anger or regret to you about the accident. It sounds to me like he values you and your friendship very much. He values you enough to have put himself at risk when he saw you were in danger. This doesn’t sound to me like a fair weather friend. And there are many ways to stay in touch. You can write letters and talk on the phone.”

“Sure, yeah.”

“I’d like to circle back to what you said at the start, about you being insistent about not having PTSD.”

“Okay…”

“It’s important to remember that everyone reacts to stress and trauma differently. You have in fact experienced a traumatic event. Your life and the life of your best friend was put in danger. For many people, acute stages of trauma may occur two to four weeks after the event itself. So it’s totally normal for your life and mental health to take some time settle back into place. You’re allowed to feel frustrated, angry, worried, scared and whatever other emotions might arise. It’s important to not rush to judge or ignore your feelings. You’ve mentioned that Ari isn’t talkative when it comes to expressing emotions, which is valid and what he needs right now to process the accident. But for you, I get the sense that you have a lot you’d like to express, either verbally or visually. Would journaling or drawing about the accident help you move forward?”

“Maybe…I usually keep a journal but I haven’t been able to write or draw much with my broken arm. When I draw with my left hand it’s like I’m in preschool again.”

“As I’m sure you know, artists express emotions in non-figurative ways all the time. If I asked you to express your feelings about the accident in abstract visual form and not worry how it looks compared to your other drawings, would that be a helpful thing to do?”

“Maybe. It still might look like chicken scratch.”

“Nothing wrong with that. If you feel more comfortable creating a collage we can try that instead.”

"I'd like to try to draw I think."

Oscar got out some paper and colored pencils and markers and charcoals for me. Instead of sitting at the kiddie table he let me sit at his desk to work. The first thing he had me do was draw how thinking about the accident made me feel.

Without really thinking about it, I picked up a black charcoal and started drawing the injured bird in the middle of the road. I used heavy black strokes. It was frustrating at first to not have complete control of the charcoal like I usually did but just putting marks and lines on the paper felt okay. But the drawing still left me with a hollow feeling.

“This is what I saw,” I told Oscar. “I saw an injured bird in the road and I went to pick it up and that’s why I didn’t see the car coming. I think I killed it. The bird.”

“And this makes you sad?”

“Yeah. I wanted to save it. But it still got killed. And Ari got hurt. It was stupid of me. I should have seen the car coming.”

“Is there anything you can do to this drawing now to make you feel less sad about it?”

“When I first saw the bird, it was on the road. But then I picked it up and held it close to my chest.”

I drew a hand around the bird, but it still didn’t feel right. Too stark and bleak. Not how I remembered the bird at all.

“The bird had colors on it. But I can’t really remember what they were exactly.”

“It’s your bird now, Dante. You can add whatever colors to it you want.”

I remembered the made-up birds I used to draw when I was little: the rainbow rocketbird, the tawny tailblaster. Pages and pages of sketchbooks filled with imaginary creatures. I hadn’t judged myself then about how anatomically accurate they were or how technically proficient I was. I drew and created because it felt good. Right now my drawing didn’t make me feel good so I added colors to my bird’s wings and I turned the hand into a nest. That felt better.

I felt calmer after my drawing was finished. But something still bothered me.

“Do you think me changing the drawing of the bird is like retconning the accident?” I asked. “I mean, when I started, I thought I would draw the bird like I remembered it. But that made me feel terrible to picture it all stiff and dark and lifeless. I wanted to protect it. Now it looks more like it’s asleep than it’s dead. But that’s not what actually happened.”

“If drawing the bird like this helped you reframe your sadness and anger into something beautiful, then I think it’s a good thing.”

“It’s not cheating?”

“No, I don’t think it’s cheating at all. In fact, I think it’s more like forgiving.”

“Forgiving who?”

“Yourself.”

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chapter 30: ‘Between the shadow and the soul’

I woke up panicked and drenched in sweat from yet another nightmare. In the dream I’d been walking on a railroad track and got my leg stuck between the wood slats in a sinkhole of pebbles. I saw a train approaching in the distance and tried to pull my leg out but it was like a cement block encased my leg and it wouldn’t budge an inch. Across the tracks, Ari saw me and came running toward me to help, only he didn’t realize the middle rail was deadly. I called his name over and over and screamed at him to stay away from the electric rail but the approaching train’s whistle overpowered my voice. He couldn’t hear me and my warning came too late.

Awake and shivering, I tried to shake off the residual fear coursing through me. I looked down at my legs, which were tingly and numb, but thankfully, still intact. I shook them out and turned over only to see my dad sitting in my comfy reading chair, with a book in his lap, dozing. The small reading light by the chair was still on and the dim blue light in my room told me it was early morning.

“Dad?” I croaked.

He woke up with a twitch and adjusted his glasses, which had fallen skewed across the bridge of his nose while he slept. “Oh, Dante. You’re awake. How are you feeling?”

“Okay. Better I think. You fell asleep in here?”

“I heard you crying out a bit in your sleep. Just wanted to make sure you were okay. Then I got caught up in reading these poems again and must have dozed off.” The book in his lap was the same Pablo Neruda one he’d read aloud to me the day before.

“What was I saying? In my sleep?”

“Just mumbling for the most part. And Ari’s name. You sounded scared.”

“Oh.”

“Do you remember what happened in your dream?”

“No, not really,” I lied. My face was already flushed but I felt it get even hotter. I knew he meant well, looking after me, but it almost felt like he’d been spying on me or like I was a baby he needed to watch over.

“Do you need anything? Tea? Breakfast? You barely ate anything but a few crackers and toast yesterday.”

I was surprised to find I was hungry, ravenous even.

“I’m starving, actually.”

“Good, that’s a good sign.” He touched my forehead. “It feels like your fever broke, thank God. I’ll warm up some oatmeal and take your temperature just to be sure we don’t have to take you to the doctor.”

“What time is it? Is it too early to call Ari?”

“It’s only 6:00am. How about you wait until after breakfast?”

“Sure, of course.”

“You sure you don’t want to talk about your dream? Was it about the accident?”

“Sort of. I’ve been having weird dreams a lot. Sometimes there’s an accident, sometimes not. But I don’t really remember them that well.”

“How’s your throat feeling?”

“Hoarse. But better than yesterday I think. It doesn’t feel like I’m swallowing a fire ball any more each time I take a breath.”

“Well that’s good, too. Here, take some more of this cough syrup.”

“Blech, it tastes so terrible.”

“I know. Just down it fast and drink this water right after.”

“You’d think in this advanced day and age of modern medical technology they’d have come up with something other than disgusting cherry poison flavor. Maybe I should forget astronomy and dedicate my career to inventing cough medicine that doesn’t taste like liquid death.”

My dad chuckled. “Well I can tell you must be feeling better if you’re planning to overthrow the cough medicine establishment. Yesterday you just drank it without a word. Now that got me nervous.”

I pinched my nose, drank the cough medicine as fast as I could and washed it down with a big glass of water. But the artificial flavor still lingered in my mouth.

“Uch, so gross. Can I break the no pop before dinner rule and have some ginger ale?”

“As long as we don’t tell your mother, I think some ginger ale for breakfast would be fine.”

“I’ll go down with you and help with the oatmeal.” I sat up in bed and a wave of dizziness crashed over me. “Oh boy. Maybe I’m not feeling so much better after all.”

“Dizzy?”

“Yeah.”

“Headache?”

“No, not really.”

“Nauseous?”

“No.”

“Okay, it’s probably just a head rush since you’ve been lying down for so long. You just stay in bed and I’ll bring breakfast up to you. K?”

“Okay, thanks, Dad.”

He leaned down to kiss my forehead and I hugged him tighter than I thought I was going to.

“Love you, Dante. I’m glad you’re feeling better today. You gave your mother and I quite a scare.”

“Love you too.”

“You know you can talk to us about anything, right?”

“I know.”

“Okay, good. I’ll be back up in a few.”

After breakfast I called Ari. I knew it was still early, but after my slew of disturbing dreams I couldn’t wait any longer to hear his voice. When he picked up with a groggy “hello?” I couldn’t help the relief that spread through my chest, releasing a tight knot I’d been holding onto for what felt like days.

“Morning,” I said.

“Dante? What’re you, my alarm clock?”

“Yeah, I thought I’d beat the early shift nurses and get the pleasure of your morning crankiness.”

“You sound weird. What’s wrong with your voice? Allergies again?”

“Nah, I got sick after I came to visit you. That’s why I didn’t call or anything yesterday. Got the flu I think.”

“Ugh, I hate the flu. The flu can wither up and die.”

“Agreed.”

“Night sweats?”

“Yeah.”

“Fever?”

“Yup.”

“Nasty sore throat?”

“You betcha.”