Text

Climate Impact Initiative // Final Statement

This semester marks my last full semester at Fordham University. I always felt as if I was an outsider at the university, even when I transferred to Lincoln Center. While I was undergoing that process and discussed it with some of my Fordham professors they immediately went: "Oh, yeah, that is a MUCH better fit for you," seeing as I come off as artsy and eclectic and so forth.

The Climate Impact Initiative has not made me regret my transient nature, but it was definitely bittersweet that I found a good niche at the university, however, one-hundred and twenty-five miles away from campus. If I had taken this class at the beginning of my time here at Fordham instead of during the swan song of my time here, I think I would have been a lot happier, found more community, and perhaps even stayed at Rose Hill.

During the second half of the semester, I estimate that I devoted between two and three hours per week to the Climate Impact Initiative. The latter half of the semester was certainly different from the former. For one, the halfway point came around the time I was finally getting into the rhythm of this class, therefore, I had a better kick in my step and more confidence with pushing the boundaries of what I believe the organization is capable of.

I worked closely with the composting team, as I found that it was where my socio-ecological niche was in a way. The goal of the compost team this semester was to develop, implement, and procure university support for a composting program. In the first half of the semester, I pitched an idea that the composting team took a considerable liking to: partnering with the Garden Club to begin the formation of a coalition for supporting composting on campus.

Although the composting team really liked the idea, I began to realize the limitations of the radical pragmatist dynamic the group, as well as the rest of the initiative holds. I believe this comes from the sort-of inward-looking condition of the organization, it is not the only organization with this issue, but it is what inhibits visibility of the program as well as discourages the sort-of coalition-style approach I wanted to take group into.

Nevertheless, I reassessed and tried to take this approach within the Climate Impact Initiative itself. I tried to act as a lynchpin or a messenger between my own composting group and the Aramark divestment/social media group. I made the case for somewhat of an internal coalition by pointing out that if we have compost bins all over campus. Aramark's plastic cutlery and packaging is sure to end up in nearly all of them, even with signs above all of the bins displaying what you can and cannot dispose of in them. Therefore, I posited, in order to have the most effective composting program possible, not just window dressing university administrators and USG officials will take credit for, we need to implement composting and divest from Aramark simultaneously.

I believe my proposition resonated well with the leadership of the group, and with the Climate Impact Initiative as a whole. I am positive I had an impact on the composting master plan drafted for the United Student Government, and influence in talks with elected student leaders.

Still, even with my newly found pragmatism within the group, my aspirations for the group continued to be lofty by their standards. I remember during one Zoom meeting for class I mentioned how my best friend, Alex Trousilek, lived in an environmentally friendly "theme house" at her school, Union College. I was delighted to hear Professor Van Buren and a couple of students in the class take an interest in it. The professor even mentioned that we should have something like that at Fordham considering that the university owns a few rowhouses surrounding the campus. That is when the gears began turning.

I mentioned the idea in an off-hand fashion during the Climate Impact Initiative meeting the following day. I explained that Union College, a school with a much smaller endowment and fewer students has townhouses across the street from its campus that all have different themes. O-Zone House, the sustainability-themed house, hosts cleanups, vegan lunches for the entire school, and other environmentally-themed events that make them an influential force on campus. I suggested that although we may not be able to just procure a rowhouse in New York City or convince Fordham to develop property in a way that would interfere with its bottom line, I think that the way O-Zone presents itself to the rest of the school should be a model for how the Climate Impact Initiative functions. While I was not surprised by the majority of leadership seeing the idea as pie in the sky, I am incredibly hopeful that the idea will carry on with the younger generation of leaders that will be running the club someday.

Overall, I left the Climate Impact Initiative with great feelings of hope that as each generation passes on leadership to the next we will be an indispensable force at moving sustainability at Fordham forward. I left more confident in my teamwork abilities. Most of all I left with a desire to continue to change the way Fordham operates. However transient I may have been during my time at Fordham, transferring from Rose Hill to Lincoln Center, then back to Rhode Island where I am finishing my degrees, it is still my educational home. When I come back to New York City, as I am certain I will, I hope that I will be able to keep my lines of communication and interaction open with Fordham University, even as I plan to look elsewhere in New York City for my graduate education. I hope and pray that I get into Columbia because if that's the case Fordham is only a 20-minute subway or commuter rail line away.

WC: 992

0 notes

Text

Blog XIV: Ditch the Desert, Come to the Ocean State

Benjamin Franklin is famous for saying there are only two things that are certain in life: death and taxes, I would also add water as another thing in life that is certain and without water, life as we know it is impossible.

Here in Rhode Island (the Ocean State) the majority of our identity is based around water, yet even we squander the water resources we are blessed to have.[] Water has increasingly been the subject of national headlines in the past decade.

As Chapter 20 of Living in the Environment points out, we kicked off the 2010s with the BP Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill. Petroleum leaked from the off-shore oil rig for three months and polluted 1,300 miles of coastline, enough to cover Rhode Island’s entire coastline three times.

Chapter 20 also notes that 2014 saw the start of the half-decade long Flint Water Crisis. Michigan’s state government poisoned the city of Flint’s water supply with lead in the name of austerity.[] The water was so corrosive that autoparts manufacturers in the city complained that they could not use the water as it tore through their parts, and people who drank the water suffer life-altering effects from the government’s cruel policies.[]

While Flint, MI held its grip on national headlines for months, if not a year or two, there is one place in particular that has held the nation’s attention since the 2010s and into the current decade: California.

Between 2011 and 2017, Californians endured the most prolonged, severe drought in recent memory, and among the longest and most intense in the state’s history.

Speaking for my fellow urban studies majors at Fordham University, from the endless sprawl and crisscrossing freeways of Los Angeles, to the expansive gentrification and strict housing covenants of San Francisco, California is the embodiment of everything that makes our blood boil. As an urban studies major, I also tend to look at California’s water woes through the lens of urban planning.

The guiding case study for Chapter 13 in Living in the Environment centers around the Colorado River. The system of dams and reservoirs that make up the river’s anthropogenic patrimony provide cities from Los Angeles, California to Boulder, Colorado with electricity, farming irrigation, and drinking water just to name a few.

The ecosystem services the Colorado River provides are already stretched to its limits. The spectacular growth of cities like Los Angeles takes a chainsaw to the natural capital it relies on from the Colorado River.

The mammoth amounts of water consumed by metropolitan populations in desert climates obscures the fact that they are in fact in the desert. Why do we continue to be shocked when there is a drought in the desert?

There is a reason why so few desert cities rise to populations as high as Los Angeles, or grow as fast as Tucson. Deserts are notoriously harsh, its arid climate coupled with scarce sources of water is the reason why many people have died crossing them.

Industrial methods of irrigation, construction of dams and reservoirs, plus the advents of air conditioning and hydroelectricity give Los Angeles the ability to hold over ten million people, and former president Trump the ability to plan his next coup attempt from what was once swampland.

Industrial technology advanced to a point where we can thickly settle environments once too harsh for us. Now, the population of Americans living in desert climates has become too large to sustain the ecosystem services and natural capital that industrialism in part helps deliver to them.

To escape what anthropogenic change has wrought in the form of endless drought, frequent wildfires, unbearable heat, and smog, I am arguing that people currently residing in desert cities should consider moving to the Ocean State.

I know that the entire state of Rhode Island can fit into a lot of desert counties multiple times and that the entire population of the Ocean State is only one-tenth to that of Los Angeles County, believe me, I know.

Rhode Island is so small, however, that if desert climate migrants concentrate in Providence, growth will not only encocmpass the entire state, but also include other states like Massachusetts and Connecticut. As the center for new climate migrants from the southwest, Providence could possibly hold its own against Boston, perhaps even New York.

I can already hear people saying that moving from the desert to the ocean is just swapping one climate crisis for another.

What I would say to that, however, is that although Rhode Island is the Ocean State, most of it is not directly at sea level as, for example, Florida is. A defining characteristic often found just feet away from our shoreline is the state’s steep rolling hills. Providence, in fact, is so steep that for a time we had the cable car system in New England, as trolleys often could not climb College Hill. For the amount of coastline that we have, I do not anticipate that even our settlements that are at sea level will be permanently lost at the mercy of the ocean. Encouraging climate migrants to move to Rhode Island could help fund sustainable coastline resilience initiatives to stave off the sea.

Booming population growth, of course, requires a lot of urban planning. We could forgo the mistakes of last century and create vibrant, affordable, sustainable, and dense communities and revitalize those that are still feeling the pains of deindustrialization.

As for what climate migrants from desert cities get in Rhode Island that they do not get in the desert: plentiful water supplies (no, we don’t just have salt water.) Although we may have to source water from other places, we have plenty of options, unlike most desert settlements that are simply not equipped to sustain such mammoth human populations.

I know that this is a far off and lofty vision, marketing the Ocean State as a climate refuge sounds like an oxymoron. To at least have a vision, is to begin lending a hand to future and current victims of the climate crisis.

Rhode Island is my favorite place on Earth, I want nothing more than for other people to make it home.

Epilogue:

Waterfootprint.org is a website where you can calculate your water footprint, i.e. the amount of water you consume in a given year

My water footprint is 645.4 meters cubed, however, the website only calculated this from my country of residence, gender (somehow,) my diet (vegetarian) and the amount of yearly income consumed by myself which I had to estimate. I do not believe that this is accurate, in fact it is likely significantly higher considering that I have a front and backyard with a swimming pool. If my parents and I lived in their childhood neighborhood of Federal Hill it would be significantly lower considering we would not have a yard, garden, or a swimming pool to tend to.

Population density within cities makes them more environmentally friendly. People in dense urban areas often use less water and less inputs of almost everything since dwellings are smaller and proximity to basic necessities is often within walking distance. Cities have to be part of the equation if we are to solve the climate crisis, just because I am closer to "nature" here on Conanicut Island does not mean living here is more environmentally friendly and less wasteful.

WC: 1,067

Question: Is anybody tracking potential migration patterns as water resources become more scarce?

1 note

·

View note

Text

Blog XIII: The Environmental Toxins Under our Noses

Last week’s blog entry brought to bear the parasitic relationship humankind has forged with the Earth’s soils through industrial agriculture. The film Symphony of Soil brought to bear the true gravity of soils around which all life perpetually orbits. What I took from the film, personally, was a reminder that the environment is not a monolith, but rather a loose federation of systematic processes, with each action taken upon it dawning an equal and opposite reaction. The speed and scale of which destructive anthropogenic actions are conducted, however, renders our perception of its effects on the environment (at least in the global North) perpetually latent. As a result, anthropogenic change for the worse marches on with near impunity, as is evident in the readings for this week.

The immense scale of anthropogenic waste and pollution defines our current environmental juncture. Efforts on the part of environmental organizations, advocacy groups, people, and governments to clean up the (often toxic) mess we’ve made is a major front in the war on averting climate catastrophe. Save the Bay, Rhode Island’s main environmental organization, conducts a yearly swim across Narragansett Bay that raises funds for pollution clean-up efforts in bayside communities. My aunt has been participating in Save the Bay swims since 2005, little did we know then, however, that pollution from Narragansett Bay and elsewhere already posed a threat to our bodily health. Chapter 17 of Living in the Environment delineates the concepts of biomagnification and bioaccumulation, both of which emphasize the systemic, cyclical nature of Earth’s environmental systems. When tourists from Newport to Narragansett carelessly discard their plastic waste, all roads for it thereafter lead to Narragansett Bay. Floating out to sea in the summer heat, these plastics degrade into microplastics that proliferate throughout the estuary and into the anatomies of small aquatic organisms which are thereby consumed by ever larger organisms, spreading microplastics throughout the food chain.

Anthropogenic waste from Narragansett Bay cycles back to its human source in the fish that are caught, brought to market, and eaten in restaurants across the state. The magnitude of microplastic proliferation is so omnipresent that microplastic particles have even been found in the placentas of unborn babies.[]

It is my view that consumers are not principally to blame for the proliferation of pollution, the blame, rather, lies in the companies that produce the products that lead to such pollution in the first place. Chapter 21 of Living in the Environment reveals how blame and responsibility is imposed on consumers. The global North produces the lion’s share of plastic and e-waste, which is then shouldered by countries in the global South. International agreements such as the Basel Convention are designed to stop this shift of waste from north to south, however, it is not enough. According to the book, the rate of domestic recycling in the United States is only about 34%. Much of the waste designated for recycling is contaminated with non-recyclable material. In this instance it would normally be my instinct to call for an expansion of environmental literacy, however, it may not be as effective or quick as forcing the companies that produce the waste that pollutes our environment to take its post-consumption byproducts and recycle it back into production. Combatting waste at the point of production is the most effective way to draw pollution down and stop the shameful export of waste to countries in the global South. The most progressive policies on this front are in the European Union. The Directive on Waste from Electrical and Electronic Goods (WEEE) and the Restriction of Hazardous Substances (ROHS) serve as models both for holding polluting companies accountable and reducing the harmful elements that pour into the environment from their products.

Unfortunately, Rhode Island and its principle environmental organization Save the Bay are not very good at doing the above. Save the Bay’s headquarters sit at the edge of the Port of Providence, the primary source of pollution in Washington Park, Lower, and Upper South Providence, the city’s most polluted and destitute neighborhoods. The large windows of Save the Bay headquarters hold spectacular views of Narragansett Bay, yet none look towards the center of gravity of its pollution. I could not think of anything better to express environmentalism’s blind spot in Rhode Island. While Save the Bay concerns itself mostly with trash pollution into the Bay, industrial interests running parallel to the port along Allens Avenue pollute Narragansett Bay with absolute impunity. Rhode Island has some of the most lax environmental laws in New England, and within the Northeast in general. As a result, activities are tolerated at the Port of Providence which would not be tolerated an hour up the road in Boston. Asphalt production, natural gas liquefaction, and scrap metal recycling are among the activities accepted at the port. Not only that, however, jet fuel, metal, and low grade radioactive material are only three of the toxic pollutants stored at the port. To make matters worse, the Port of Providence is on the wrong side of the Fox Point Hurricane Barrier. In my experience Rhode Island typically gets battered by tropical storms at least every five years, at most, ten years. With Hurricane Sandy being the last severe storm in recent memory, we are nearly overdue for our next hurricane. If the port floods and pollutants spill out, saving the Bay will be rendered a pipedream.

The industrial interests stationed at the port hold the economic gun to Rhode Island’s head, threatening dire consequences for the money-starved state if they are regulated or pushed out. However, if they aren’t regulated, Rhode Island loses its link with the ocean, the core of its identity as a state. If Rhode Island made its premier port for people, on the model of Boston, MA or Portland, ME, I believe that it would create a bigger economic boon than what industrial interests could ever dream of offering. If Rhode Island continues to bend to the will of corporations, however, the environmental degradation of Narragansett Bay is an inevitability.

Question: Our current environmental juncture requires us to think big and boldly in order to clean up the mess we’ve made, yet our vision seems to be razor thin these days, how do we begin to think big again?

WC: 1,004

0 notes

Text

Blog XII: About the films Symphony of Soil and Food Inc.

My blog from last week mainly focused on aquatic biodiversity with an additional epilogue of sorts that turned towards what is perhaps the oldest socio-environmental relationship of modern civilization: food production and securing food. This week we will focus on the latter more closely informed by the film Symphony of Soil.

The film immediately sets out to (literally) get in the dirt by informing viewers of soil’s physicality. As terrestrial beings, we have always been able to rely on soil, we’ve allowed ourselves to take agricultural land for granted as food magically appears on our store shelves, pantries, and refrigerators. Soil forms the crux of the world’s chemical and nutrient cycles which underpins the functionality of ecosystems far and wide. In essence, soil is the ecosystem service of ecosystem services, allowing for everything required for life on land to be possible. Of course, soil is not a stagnant feature of the environment, as nothing in our environment is truly stagnant. The soil that we are endowed with today is the result of millions of years cycling nutrients and chemicals and climate change (not the kind humans are causing though.)

Today our excessive wants from the Earth’s soils is endangering its health, and therefore the health of the ecosystems it supports, of course, including ours. Soil is called the “living skin of the Earth” in the film, if that is the case, we are skinning it alive. Soil is not simply some magic dirt where we can create something from nothing, the food soil helps us grow requires the culmination of several chemical, nutrient, and energy processes, take away just one of these processes and the nutrition our species has evolved to rely on for thousands of years disappears, likely along with much of our species. Therefore it is important that we maintain a symbiotic relationship with the soil, not a parasitic one. Parasites never intend to kill their hosts, but in our case we are blindly killing grade A agricultural land that has somehow been able to accommodate seven billion of our species. The excesses of food that we grow come about through destructive farming practices which quickly renders the soil it tills infertile all in the pursuit of economic growth. The mammoth amounts of greenhouse gases industrial agriculture produces is also changing our relationship with the soil. Subsistence farming may see a sharp decline as their crops suffer from the whiplash of climate change, leaving the door open for corporate buyouts that will continue to hasten the problem.

On the bright side, I believe that agriculture and food production is one of the most hopeful, prosperous fronts of sustainability in the battle against the climate crisis. People are rediscovering their connection with land, soil, and food. In Upper South Providence, notably, a food desert, entire blocks have been transformed into gardens for growing fresh food. A thousand miles away in Detroit, the nation’s first food-self-sufficient neighborhood has cropped up. Locally grown produce, whether in area supermarkets or restaurants is desirable, Whole Foods marks foods on its shelves that are locally grown. These trends are indicative of modernity’s undoing, at least where food and agriculture is concerned.

A sizeable portion of the film centers around the Green Revolution, an effort on the part of Western nations and philanthropies to industrialize agriculture in poorer, often freshly decolonized nations. The Green Revolution posited that industrialized agriculture and the massive amounts of inputs it requires for the mass production of foods would be a boon for farmers. The film depicts how the Green Revolution is going nearly half a century after it started. The introduction of pesticides, herbicides, fertilizers, and GMO seeds the Green Revolution promoted are not what they used to be, and farmers in places like India, Mexico, and the Philippines are losing faith, even succumbing to deaths of despair when their yields fail to meet expectations. Indian environmental activist Vandana Shiva asserts that India would have the same amount of food if not more if subsistence farmers that tilled the land for thousands of years were empowered instead of rendered redundant.

While Symphony of Soil focuses on the scientific anatomy of soil and problematic aspects of our socio-environmental relationship with it, Food Inc. is more blunt regarding the consequences of said dynamic. The film posits that because of our worship of economic growth, our demands upon soil and livestock are overflowing. Farmers are forced to hold their livestock in conditions that encourage diseases to arise and pass onto humans, and monocultures of cheap crops are used to feed their excessive amounts. Against the current backdrop of the COVID-19 pandemic, it is clear after watching Food Inc that the next disease we will encounter is likely lurking just around the corner of a barn. If we do not stop these practices and create a more sustainable agricultural patrimony, we may have to have our masks handy indefinitely. Activists and journalists have undergone amazing feats of investigation to expose the problematic practices of heavily commercialized farming.

In my view, food sustainability in the United States is one of the easier problems we can solve to avert the climate crisis. Food waste, for one, can be solved with composting programs and education. Compost can effectively replace a substantial amount of fertilizers that contaminate ecosystems. The nitrogen many fertilizers are composed of will enter the ecosystem through sustainable means, hell, maybe people could even sell their compost to local farms in exchange for lower prices on food they sell, that could be a great framework for divesting from environmentally destructive corporate farming. We also need Congress and the Environmental Protection Agency to step up to the plate when it comes to regulating harmful chemicals, which in some cases, have not been regulated since before the postwar era. Criminalizing lobbying government agencies like the Environmental Protection Agency would be a good place to start, so that when a chemical comes under their scrutiny, civil servants are not influenced. I believe that we need to wrestle the power over what we consume willingly and unwillingly from chemical and agricultural companies like Monsanto and Dupont. Such conglomerates have shown that profit is their God, and they will serve it by any means necessary, even if it means slowly poisoning populations or depriving farmers of rights to their crops. In holding them accountable, we can make room for more and better seeds than what they force farmers to plant at a premium, promoting genetic biodiversity and mitigating the risk of food shortages.

WC: 1.084

Question: Is urban agriculture just something that sounds good on a powerpoint, or is it really an effective lynchpin for increased food-self-sufficiency in urban areas?

0 notes

Text

Blog XI: Threats to Aquatic Biodiversity, Ecosystem Services, and Natural Capital in Narragansett Bay & The Northeast as a Modern Breadbasket

In last week’s blog post, the focus was on biodiversity loss from both species and ecosystem points of view. The subject in question for this week concerns the definitive underpinning of species and ecosystems: land and water. When we harm or heal any ecosystem or species, the core of such dynamics reflects our fundamental relationships with land and water, without which not much at all would exist on Earth as we know it. Chapter 11 of Living in the Environment deals with our aquatic ecosystems, and Chapter 12, our land environment. Being that we are in the Ocean State, let's start with the former.

The Atlantic Ocean is Rhode Island’s principal ecosystem service and supplier of natural capital. With each ocean current, the pollution we create is filtered out of our vicinity, the ocean itself also absorbs a substantial amount of the greenhouse gases we produce. Our unmatched beaches and top-tier seafood draws (to my annoyance) tourists from all over the globe. Clean energy is even on the list of natural capital we derive from the ocean, as we host the first off-shore wind farm in the United States, just off the coast of Block Island. Rhode Islanders are used to salt-water as much as the lobsters and quahogs we catch, but we also take our biggest ecosystem service for granted and put it in harm's way unnecessarily. We advertise our picturesque beaches and seaside colonial towns to tourists, and many people come to Rhode Island just to live in such an environment. What most people avert their eyes to are the obvious harm we do to the ecosystem which is nearly a namesake for our state. To see the harm Rhode Island does to the ecosystem its people and government claim to cherish, look no further than the Port of Providence.

In 2016, Governor, now Secretary of Commerce Gina Raimondo, gained herself a great deal of praise when she helped facilitate the completion of the nation’s first off-shore wind project.

Three years later, she nixxed her own health department’s concerns for constructing a new natural gas liquefaction facility at the Port of Providence and greenlighted the project. For my senior thesis I spoke with journalist Steve Ahlquist who has done some work on the Port of Providence, and he revealed to me that we store things there that other states and other towns would never allow. Jet fuel for Boston’s Logan Airport is stored at the Port of Providence, of course, Boston would never allow jet fuel to be stored on their historic waterfront, but we do. It isn’t just jet fuel, scrap metal recycling, asphalt and cement processing, and recently an old Russian submarine (which sank and caused an oil spill) are among the many environmental harms and hazards of the Port of Providence. To top it all off, the city’s hurricane barrier doesn’t even protect it, so it is plausible that a chemical evacuation zone would have to be created in a radius surrounding the port, should we have another Hurricane of 1938 or Hurricane Carol. The port is also built on landfill, so all that is there amounts to a powder keg of oceanic pollution that threatens our estuary's ecosystem and the vast array of aquatic biodiversity within her.

It is appalling that a state that calls itself the Ocean State has such a disgraceful, wasteful, environmental ticking-time-bomb of a port. In hosting polluting industries at the port, Rhode Island as we know it is committing suicide each and every day. With Greenhouse gases comes ocean acidification, the types of things that are only widely known to happen in places like the Great Barrier Reef. Remember how I said that the ocean absorbs much of the greenhouse gases we produce, yeah, it does not come without a cost.

Ocean acidification means that Rhode Islanders will have to say goodbye to their beloved oysters and clams on the menus of their favorite restaurants, as their shells cannot handle acidic pH levels. Clam cakes and chowder will not be on the menu at Aunt Carries’ in Narragansett, and there will be no more backyard clambakes in Westerly, Newport, or Wickford.

The disappearance of just one species, however, is only the tip of the iceberg. Ocean acidification induced by greenhouse gases constitutes a molecular nature of the ocean, with such a shift, keystone species and ecosystems will simply not exist here anymore. We can only predict the full scope of changes that will occur within the Narragansett Bay Estuary in the distant future, but the chain reaction of eroding ecosystems and plummeting biodiversity caused by ocean acidification will come at a steep price, not only economically, but also spiritually and culturally.

The core case study of Chapter 11 explains what will certainly be on the menu, however: jellyfish. Although they are considered delicacies in Asia, they have not caught on in North America, which is about to change. The book mentions that Chinese oceanographer Wei Hao brought attention to the consequential implications of booming jellyfish populations on marine ecosystems, indicating that as they grow they will be here to stay for millions of years. This has grave implications for the future of aquatic biodiversity. As jellyfish populations grow, and the populations of other marine species dwindle, flee, or disappear, they are surely going to be a regular face on the menu. Instead of bragging about having the best lobsters, clams, or oysters in the country, Rhode Islanders and our fellow New Englanders will be bragging about having the best jellyfish.

I have even noticed more jellyfish when I went swimming at numerous beaches last summer. In 2019, Rhode Islanders I knew theorized that we were getting a lot more tourists from Massachusetts that year because rising water temperatures meant shark and jellyfish populations were making their presence known in places like Provincetown, Hyannisport, and Nantucket. While Rhode Island hasn’t seen any sharks yet to my knowledge, I can say with certainty that the jellyfish are out to play. At Misquamicut State Beach I nearly dove headfirst into a jellyfish’s tentacles when I was body surfing the waves. At Second Beach in Middletown, my friend Alex and I swam to Purgatory Chasm to go cliff jumping. On our way to Purgatory Chasm, we were literally wading through moon jellyfish, with each stroke forward we could feel them across the length of our arms.

When all is said and done, however, we are extraordinarily blessed that we do not yet have to bear the more dire consequences of climate change that billions all over the world are already feeling today. All that this blog has been about so far is some changes to the menus of restaurants. I have the blessing of not having to speak as the son of a fisherman, a restaurant owner, or a resident abutting the Port of Providence. Being aware of these issues from the outside is not enough though, and I fully intend to take what I’ve learned to the state’s foremost environmental organization, Save the Bay, and ask them: Why the hell aren’t you doing anything about this?

The Providence neighborhood of Washington Park is home to the Port of Providence, which hosts some of the egregious, toxic, and harmful pollutants and polluting industries likely at some of the highest concentrations in the state. Save the Bay happens to be headquartered at the very edge of the Port of Providence. Monica Huertas, a local environmental justice activist from Washington Park pointed out to me that Save the Bay headquarters has big windows that give one hundred eighty degree views of the Narragansett Bay; yet there are no windows to the heaps of asphalt, jet fuel storage tanks, and natural gas liquefaction facilities that are only feet away––constituting a powder keg of environmental destruction. Save the Bay headquarters is a remarkably sustainable property, complete with green roofs, bioswales, and even restored marshlands; it represents what the Port of Providence could and should look like if not for the occupation of powerful, polluting industries. I find it baffling that there is not a single mention of the Port of Providence on Save the Bay’s website. Save the Bay says: “Our mission is to protect and improve Narragansett Bay. Our vision is a fully swimmable, fishable, healthy Narragansett Bay, accessible to all… We watch over the government and citizenry for proposals or activities that will degrade the environmental quality of the Bay, basin, and watershed… We actively work in the field to rebuild and restore habitats compromised by pollution, outdated infrastructure, storms, and sea-level rise.” Is the fossil fuel infrastructure at the Port of Providence not outdated? What about the eight-lane highway that runs adjacent to the Bay? Do piles of asphalt that lay mere feet away from the Bay not constitute degradation of the environment?

Save the Bay fetishizes a pristine, almost romantic version of Narragansett Bay. These images are so ingrained that portions of the Bay are virtually unrecognizable as part of the “natural” environment, such as the Port of Providence. This makes for pernicious blind spots which obscure the human costs of environmental harm and the blindly accrued human causes of environmental destruction, such as transportation. Every window opens up to Narragansett Bay, but there are no windows facing what is arguably Narragansett Bay’s pressing environmental problem: The Port of Providence. If the port floods, and the equipment or structures upon it is damaged, it spells grave danger for the aquatic biodiversity of the estuary.

Part II: Food Insecurity

It may sound redundant to say that food comes from land, but somehow, I believe that it is necessary. In a market economy we often forget that our food does not originate from a market, it comes from stewardship of the soil. Chapter 12 of Living in the Environment sits at the juxtaposition between the environmentally destructive ways we grow the food many of us consume today and malnutrition. The post-war era brought with it the mystique of modernity, and the mirage of its so-called “progress.” Modernity brought with it radically different approaches in which we produce and consume food. Corporations in the United States developed industrialized agricultural technologies like pesticides, herbicides, and fertilizers and techniques that require high inputs of water and energy, creating massive surpluses of food.

The United States exported these techniques and technologies to the rest of the world, notably through philanthropic efforts like the Ford Foundation and Rockefeller Foundation. The Green Revolution became the North Star for these philanthropists. They assumed people who used traditional means of agriculture, growing their own food and perhaps dabbling in markets without being reliant upon them were poor. If you can provide the basic necessities of life for yourself, it does not make one poor no matter how one goes about it. Western philanthropists thought that former subsistence farmers would live an urban-western lifestyle in that they would no longer have to produce their own food with the immense scope and scale of industrialized agriculture. The agricultural techniques of tomorrow back then are showing their age. Industrialized agriculture stripped vital nutrients and minerals from the soil, and intensive irrigation has led to waterlogging. Weeds and pests have built resistance to pesticides and herbicides, and fertilizers no longer produce what they used to. As a result, countries that were once testing grounds for the Green Revolution are reverting back to traditional agricultural techniques and even using the seeds that industrialized agriculture sought to replace, adding more genetic biodiversity into the agricultural patrimony.

In the twenty-first century, I think we are rethinking where modernity has brought us, in seeking to find a solution to all our problems, it has become the problem. The United States has been at the forefront of agricultural modernity for generations. Agricultural modernity essentially rendered small breadbaskets like New England and Upstate New York redundant. Having the rugged land, soil, and variable weather conditions we have up here, producing food was not as conducive to profit as it was in the Midwest, but I believe that is changing. Entire blocks in Upper South Providence have been converted to food production. The hippest and happening restaurants source all their food locally, with Rhode Island being as small as it is, that often means food is sourced just down the street.

The Northeast is an interesting place geographically. When French geographer Jean Gottmann wrote his book Northeast Megalopolis he noted that just outside of our major cities were vast swaths of farms. In any other region, such parts would be considered rural, but we have achieved such immense population densities that the “rural” folks of our region’s breadbaskets live an urban-esque existence. As a life-long northeasterner, I can attest to this. About 500 feet away from my house is a community farm where my family often gets food during the summer months. Within a five-mile radius of where I live there are at least a dozen farms. My town only has a year-round population of about 2,500. Yet if I drive for half an hour, I’m in Providence, a city of about 200,000, if I drive an hour, I’m in Boston, which has a population of 700,000. If I were in any town similar to mine in another region I would be in a rural setting, the nearest city would be a road trip by Rhode Island standards.

I think that the Northeast has great potential to grow a regional network of sustainable agriculture forming strong urban-rural food networks in which cities and the rural parts of their metropolitan areas source what food they can directly from their metro area. Perhaps states could encourage this through tax incentives upon restaurants and grocery stores to buy local products from small independent farms and thereby put money in the pockets of the surrounding area. Of course, cities should start growing their own food, but we already have such a good framework here in the Northeast for creating sustainable agriculture networks, and if we can do that, while also filling in the food production gaps within cities–– we could become a model for the rest of the country.

Most importantly, by empowering small local farms, we can ensure a larger genetic consortium of biodiversity in our foodstuffs. Biodiversity underpins food security. With just a few varieties of the types of foods that we eat, we are betting a lot that said food will be highly resilient to what nature throws at it and not fall victim to disease or death, two things we ought to think a lot more about considering the current pandemic we are coming out of, but can just as easily fall back into.

WC: 2,440

Question: How do we convince people that we will have enough food if we ease up on industrial agriculture?

0 notes

Text

Blog X: Rhode Island's Marshland Must Be Saved from the Current Real Estate Boom.

As mentioned in previous posts, especially last week, the primary leitmotif of our socio-environmental system is humanity’s unprecedented population growth and our rapid urbanization–– where more and more people live in expansive and enlarging metropolitan areas than at any point in human history. As the population of our species increases vertically and laterally across space and time, it does so at the expense of landscapes fortunate enough to remain unexploited, albeit not necessarily free from anthropogenic impacts. For our purposes here, I intend to emphasize the importance of biodiversity that we cherish and rely upon every day in the Ocean State–– additionally, I will point out some of the human dynamics of our socio-environmental system that are problematic and threaten to erode or destroy the unique environment we are blessed to inhabit.

The ninth chapter of Living in the Environment focuses on the importance of biodiversity as it applies to wild animal species across different habitats, and the problems anthropogenic influences present to the survival, functions, and maintenance of biodiversity in ecosystems. Oftentimes I find that initiatives to save particular species (even keystone species) do not emphasize the important roles they play in the ecosystems they inhabit. For example, the book mentions the endangered orangutan’s role in dispersing seeds in their waste that would not propagate without them. The tenth chapter of Living in the Environment delineates the parasitic relationship between humans and ecosystems that threaten the natural patrimony which all species of the Earth rely upon. Sustaining and saving the biodiversity of ecosystems is imperative to maintaining the economic value and support they provide through, for example, reducing soil erosion, providing for recreation, and nutrient cycling–– all of which, unfortunately, is hidden due to the absence of full-cost pricing. The authors estimate that the economic value of the various services forest ecosystems provide are worth least $125 trillion per year, one and a half times higher than the world’s total GDP in 2018. Despite the mammoth economic benefits humans derive from forest ecosystems, they are the first to be sacrificed in blind pursuits of economic growth–– evident in the expansion of agriculture and the construction of highways and housing. The various pressures humans impose onto species and ecosystems erode their biodiversity with near impunity. The United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity’s fifth “Global Biodiversity Outlook” and the New York Times article entitled “A Crossroads from Humanity: Earth’s Biodiversity Is Still Collapsing” underscore the magnitude of anthropogenic erasure of biodiversity and the latent effects it will have on our species.

What I found most striking about the United Nations report is its insistence that we must depart from business as usual, and that doing so entails reducing our consumption in order to ensure that justice for the generations that will inevitably inherit the natural patrimony we have taken for granted and are tasked to restore. The Rhode Island town I reside in, Jamestown, is a state-champion in sentimentalizing nature, evident in the conservation and restoration efforts of our natural landscapes. Unfortunately conservation and restoration efforts are on the bottom-rung of actions to reduce loss of biodiversity, yet it is arguably all that one needs to not feel guilty or anxious about the climate crisis.

Biodiversity researchers use the abbreviation HIPPCO (Habitat destruction, degradation, and fragmentation; Invasive species; Population growth and increasing use of resources; Pollution; Climate change; and Overexploitation) to summarize the most pervasive anthropogenic threats to species biodiversity. Unfortunately, Rhode Island harbors critical levels of such threats to biodiversity, especially habitat degradation, pollution, invasive species, and of course, climate change.

I want to focus on The H in HIPPCO is quite extensive–– standing for habitat destruction, degradation, and fragmentation. Out of the three threats to biodiversity within habitats, I view habitat fragmentation as most consequential for Rhode Island’s species biodiversity. Just down the road from me in Jamestown, RI, the town maintains a public golf course. I have no idea why. Much as the rest of the state does, Jamestown prides itself on its natural patrimony. Eco-friendly stickers seemingly adorn the bumpers of every other car on the island, indicative of Jamestown’s oxymoronic dynamic with Conanicut Island. Next to the golf course lies a delightful bird sanctuary that I stroll in from time to time. Being that the island is at most only a mile wide, it only takes me a little over ten minutes to make it to the opposite end of the sanctuary, where it touches Jamestown’s Marsh Meadows Wildlife Refuge. Marshlands are special ecosystems, perpetually at the transition between sea and land, as a result they accommodate species not found in any other ecosystem. Much of the natural capital from commercial fisheries derives from the ecosystem services of salt marshes and estuaries for nursery and spawning grounds. The Marsh Meadows are marshlands within an estuary. Marshlands also provide indispensable ecosystem services to society as a whole by intrinsically filtering pollutants, producing oxygen, recycling nutrients, and removing sediment. The Rhode Island Department of Environmental Protection estimates that over half of the state’s salt marshes have been lost, and today only under 4,000 acres remain–– most of which are impacted by human activity, unfortunately Marsh Meadows is an exception. Pollutants like pesticides, herbicides, and fertilizers naturally runoff into the marsh from the nearby golf course. The North Road Bridge partially fragments the ecosystem’s western flank, while the highway to the Newport Bridge completely blocks the marsh from draining out into the cove by my house. You can still tell that the area was once marshland though. A freshwater pond popular with Canadian Geese and the occasional egret is present next to the building occupied by the Rhode Island Turnpike and Bridge Authority. The lands next to the building routinely flood since the faux ecosystem of maple oak and pine trees that the RITBA planted there simply does not belong. The force which causes the most habitat fragmentation, degradation and pollution, however, is the public golf course. While it does not exactly fragment the landscape like a road or a bridge it is so cumbersome that in my opinion the marshlands hardly have any room to breathe. Not all the course sits on top of the marshlands, and the parts that do obviously are not suitable for golf, however, the chemical pollution from lawn treatment is enough justification for me to call for the dismantling of the course. Even if its size is reduced to give the marshlands more breathing room, the incursion of pollution is still too great a cost to the natural capital and ecosystem services that marshlands provide us. The town of Jamestown ought to put its money where its mouth is if it wants to retain its brand of a crunchy eco-friendly town.

While Marsh Meadows is not under an immediate threat of total habitat destruction, as it is a protected area, substantial amounts of unprotected marshland also exist on the island around Mackerel and Sheffield Coves. The two coves are only feet away from each other, separated only by a small land bridge. Mackerel Cove is a popular beach with tourists and locals alike as it offers picturesque views of the Atlantic Ocean. Sheffield Cove is more of a local secret, it has a rocky shoreline and a decent amount of marshland with adjoining private properties far enough away that they do not appear to render any significant incursions within the ecosystem. Mackerel Cove is a different story. Last summer a huge McMansion was built on the last remaining marshland the cove has. Even more worryingly, the dunes created to protect the beach seemingly also incurred destruction, as the fences protecting them from getting trampled by beachgoers, pets, and cars have been inundated by storms. This is a grave mistake and indicative of the town’s environmental negligence. The Netherlands, which has been battling the seas for over a millennia, routinely uses plants and maintains dunes to keep back the tides of the sea. Closer to home, East Providence recently rebuilt their dunes to protect their shorelines from flooding and sea level rise, and Jamestown squanders the ones they already built. The town’s environmental negligence, however, may not be intentional. Jamestown has incredibly low municipal taxes and a NIMBY sentiment so strong that even pre-pandemic business tax revenue is scarce. If one dares to build a multi-family or mixed use building, they face the ire of the opposition who have nothing better to do than peddle in racist and classist dog whistles. At the cove near my house a volunteer effort was coordinated to restore a good portion of its natural habitat, dunes, and even some marshland, but we cannot rely on volunteers to do all the work that needs to be done. Jamestown ultimately needs to combat its NIMBY sentiment, allow growth in its small urban core, and raise taxes (which mostly everyone here can afford) in order to deal with its coming environmental woes.

In conclusion, when it comes to a species approach or an ecosystem approach to combating terrestrial biodiversity loss and extinction, I tend to fall heavily in the ecosystem approach. I must point out though, that the two approaches go hand and hand and need each other to achieve their common goal of preserving, protecting, and restoring biodiversity. Without the wolves of Yellowstone National Park, for example, the ecosystem would fall out of balance as it was prior to their reintroduction. If wolves again ceased to exist in Yellowstone, the animal populations they kept in check would erode much of the park’s natural capital once again, beavers would not have materials to build their dams, and riverbanks would erode. Therefore, in a sense, animals are their ecosystems and ecosystems are the animals within them. I believe that I tend to fall under the ecosystem approach, however, due to my love for geography and environmental planning. Plus, New England is such a tamed ecosystem (as in, if I walk outside a wild animal likely won’t kill me.) Maybe I simply do not notice the ways in which animals in my neck of the woods affect the ecosystem I live in because of an evolutionary complex that allows me not to expend as much energy thinking about them. I’ve always been able to scan my ecosystem in the various geographies I inhabit here, I’ve never had to scan it for animals that could kill me. If bears and wolves made their return here, however, as they allegedly have in north and west of Providence, that would probably be better for the ecosystem, hence the intertwined nature of both approaches to restoring biodiversity.

WC: 1,760

Question: Would tax credits for increasing the biodiversity of one’s yard (as is proposed in Rhode Island) be effective in increasing biodiversity in general?

1 note

·

View note

Text

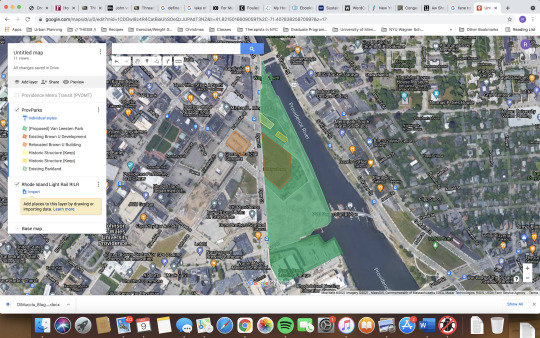

My Proposal for an Expanded Public Park along the Providence River

0 notes

Text

Blog IX: Providence Lost a BIG Opportunity for Environmental Planning.

The number of living people on planet Earth reached one billion people in 1804, an unprecedented milestone after 200,000 years of our species’ ascendence. Although it took 200,000 years for the human population to reach one billion people, it took only 200 to reach seven billion. In 2009, humanity cleared yet another milestone, the number of people residing in cities exceeding those living in rural areas for the first time in human history.[1]Current population trends centuries in the making act in tandem with the current climate crisis, of which more humans than ever will be forced to deal with in the twenty-first century and beyond.

Chapter six of Living in the Environment heavily focuses on Earth’s carrying capacity–– i.e., the number of people that existing natural capital and ecosystem services can adequately support. Debate about the physical boundary to human growth has gone on for centuries. Notably, in 1798, Thomas Malthus hypothesized that exponential population growth coupled with comparably stagnant food production created a proverbial ceiling for the exponential population growth he identified. Of course, during Malthus’s time, industrial agriculture was somewhat of an oxymoron, he could have never predicted that food production too would also increase exponentially due to industrialized agriculture.

During my History of Capitalism, I was required to read Planet of Slums by Mike Davis. The book delineates an environmental history of what is perhaps the ultimate rejection of Malthus’ hypothesis: The Green Revolution. After World War II, philanthropic efforts on the part of the Ford Foundation and the Rockefeller foundation introduced industrial agriculture technologies such as pesticides, fertilizers, irrigation infrastructure, and high-yield crop variants to what they saw as destitute peasant populations, most notably in India, Mexico, and the Philippines. Although the intentions of the foundations were good, (although incredibly utilitarian in hindsight) what ensued was the disenfranchisement of peasants from their land, followed by the swelling of slums encircling cities such as Mumbai, Mexico City, and Manila, contributing the lion’s share of urban development globally. The Ford and Rockefeller foundations assumed that the peasants, needing not to grow their own food any longer, would live a metropolitan urban lifestyle as they enjoyed in the West.

Urban slum dwellers in the global South account for the majority of the world’s urban expansion. In summary: More people today are living in cities today but in the ever-expanding rings of slums within and surrounding cities. I can already see North American urban planners looking at global urban demographics and concluding that the pro-urban sentiment espoused by the authors of their dogma over the years has finally caught on, and people are ascending to a new urban rapture. Slum-dwellers, the vast majority of urban populations in the Global South, endure the most reprehensible environmental conditions in the world. The largest city in North America, Mexico City, has a dirty environmental secret that foreign visitors to places like Chapultepec Park seldom know. The city hoards several tons of feces in open-air garbage dumps, located next to or on top of the city’s slums. Slum-dwellers are known to scavenge dumps and landfills in hopes to find something of sustenance or utility, and particles of shit carry through the air often irritating the throat and lungs of people unfortunate enough to be in proximity to them. In Mumbai, not many people other than slum-dwellers shoulder such disproportionate burdens of climate change. Slum dwellings are often constructed out of scrap metal with no ventilation or proper insolation. When monsoon season arrives dwellings often flood, and when the water drains out it leaves mold behind to be perpetually inhaled. The tin walls and rooves of slum buildings in the summer make the unfortunate residents inside feel like they’re baking, even more so with rising temperatures.[]

North American urbanists may think that cities have a default setting towards environmental friendliness, as we see in the global South, they do not. This sentiment may come from, the improving environmental condition of cities in the Global North (although they have a long way to go.) Mayor Bloomberg’s “PlaNYC” initiative provides excellent examples of what cities ought to do in order to effectively mitigate climate change. Two things from the plan I find incredibly interesting are congestion pricing and the creation of beautiful waterfront parks, perhaps the most physical representation of Bloomberg’s legacy (aside from rebuilding from the rubble of Ground Zero.) Congestion pricing in New York City is effectively a toll on vehicles moving in and out of Midtown Manhattan during times where traffic is heaviest. Cities such as London, Milan, and Stockholm show that levying tolls on rush hour traffic is an effective way to incentivize transit ridership and get carbon-emitting cars off the road. The majority of New York City residents don’t even own a car anyways[2], making the weight of each resident’s carbon footprint a whole lot lighter. Fewer cars on the road equates to lower carbon emissions. Unfortunately, however, New York City lags behind its international counterparts due to the reluctance of Trump DOT under Secretary Elaine Chao to implement anything of the sort. Biden’s DOT, however, recently lifted the roadblocks to congestion pricing leftover from the previous administration, and the city should be set to implement it in a matter of months.[3]

The Bloomberg administration also constructed some magnificent and beloved waterfront parks on top of former industrial sites. One of the best examples of this Bloomberg initiative is Brooklyn Bridge Park (BBP.) The park makes for a great case study in sustainable design,[4] I believe that it represents part of what other coastal cities in the Northeast ought to be doing with their waterfronts to mitigate the effects of climate change. Old industrial piers on the edge of Brooklyn Heights were transformed into Brooklyn Bridge Park using recycled wood and granite for park benches, structures, and decking, as well as recycled fill material from the (long-delayed) East Side Access Project. BBP also restores vital habitats of native plants, birds, and marine life by recreating the salt marshes and meadows that were destroyed as Brooklyn grew. Notably, the BBP also partnered with the Billion Oyster Project to restore oyster reefs to the Hudson. The reintroduction of oysters is in large part responsible for the estuary’s dramatic environmental turnaround from a deathly polluted waterway to a place where even whales and seals have returned.[5]

Providence has the opportunity to create its own iteration of a Brooklyn Bridge Park-style sustainable green space, but that opportunity is already diminished and threatened to be completely decimated by development. In 2002 the Rhode Island Department of Transportation completed work on relocating an old elevated viaduct of Interstate-95 that separated Downtown Providence from the Jewelry District for over half a century. While I would have preferred the complete demolition of I-95 within Providence, still, it was a great first step by the state’s tragic history of land-use planning. Being such a poor city, however, and desperately wanting to scrape off residents from Boston and New York, the city put as much land as it possibly could up for development.

While a sustainable park was implemented in the execution of the former I-95 land’s master plan, it is much smaller than it needs to be. Therefore, the park’s potential utility as a public amenity that both protects Downtown Providence from rising sea levels and provides Providentians much-needed greenspace is considerably diminished. Even the existing parkland is threatened by a high-rise mixed-use luxury condominium building that would become the tallest structure in the state.

If I were in control of land-use planning of the land formally under the Interstate, I would strictly follow the Smart Growth Tools outlined in Chapter 20 of Living in the Environment. First, I would cordon off everything east of Dyer Street from development and hire the same landscape architecture firm that built Brooklyn Bridge Park to build a park on the model of BBP. Certainly, I would make the blocks of the new streets way smaller as to fit in with the historic streetscape of Downtown Providence and the Jewelry District to promote a mixture of uses and encourage transportation alternatives to automobiles. Scattered across the blocks I may create smaller urban parks on the model of those such as Father Demo Square in Greenwich Village. Some of my zoning ordinances would impose constrictive parking maximums instead of minimums, call for each building to implement green roofing, and encourage density and the mixing of uses, and inciting tax incentives would be offered to buildings that achieve high LEED ratings. Unsurprisingly, none of these incentives are being implemented by the State of Rhode Island or the City of Providence.

When Superstorm Sandy hit New York City, Brooklyn Bridge Park withstood better than city officials expected. The park absorbed much of the blow the storm dealt to surrounding neighborhoods.[6]Unlike New York, Providence has the geographic advantage of not being a low-lying archipelago. The city’s geography is characterized by steep rolling hills and deep river valleys and flatlands, the former comprises more of the city than the latter. Therefore, the city is naturally going to be more resilient than many of its northeastern counterparts. The only parts it needs to protect is its immediate waterfront and the flatland valleys of Downtown Providence. It seems as though the city’s urban planning department has been reduced to a wealth management agency. They would rather boost property tax rates and cram as much new development they can under the city’s arcane zoning laws rather than conserve and protect our irreplaceable, historic urban patrimony with a public amenity capitalized on to its full potential.

WC: 1,559

Question: The "15-Minute City," where people can find all of their needs and wants within a fifteen-minute walk from their home is often cited as one of the strongest answers cities give to climate change, by inducing less consumption (especially in the transportation sector.) However, I fear that designated 15-Minute city areas could become enclaves for the rich. Arguably, places like Greenwich Village in New York, or Wayland in Providence are already rich enclaves of the 15-minute city.

If we do not address inequality while implementing 15-minute city plans, will all

the environmental benefits be offset by the larger consumption habits of rich populations?

[1] United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs: Population Division https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/publications/urbanization/urban-rural.asp#:~:text=By%20the%20middle%20of%202009,urbanization%20remain%20among%20development%20groups.

[2] NYCEDC: New Yorkers and Their Cars, https://edc.nyc/article/new-yorkers-and-their-cars#:~:text=According%20to%20recent%20census%20estimates,own%20three%20or%20more!).

[3] Kuntzman, Gersh. Congestion Pricing May Not Go Anywhere Unless Biden Wins, Mayor Says. Streetsblog NYC, 14 July 2020 https://nyc.streetsblog.org/2020/07/14/congestion-pricing-may-not-go-anywhere-unless-biden-wins-mayor-says/

[4] https://www.brooklynbridgepark.org/about/sustainability/

[5] https://untappedcities.com/2021/02/03/history-new-york-city-oysters/

[6] https://www.ecolandscaping.org/01/managing-water-in-the-landscape/stormwater-management/weathering-the-storm-horticulture-management-in-brooklyn-bridge-park-in-the-aftermath-of-hurricane-sandy/

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Socio-Environmental Economy (Class 8)

Our current era is defined by people and their governments being forced to grapple with three centuries of industrial capitalism. Environmental economics, the topic of this week’s class, seeks to understand the fundamental link between our economic system and the environment; one simply cannot exist without the other, yet capitalist economic order acts entirely separate from the environment it derives the value it claims to create. I believe that industrial capitalism causes humanity to perceive itself as separate from the environment, paradoxically humanity’s actions within the environment have never been so profound. As the consequences of industrial capitalism crescendo in the twenty-first century, it is vital to speak its language (economics) in order for political economy to come to grips with the environmental devastation that could cause its downfall.

Consumer or Citizen? asks us the question: are we citizens of Earth or consumers of it? I believe the problem with our economic relationships with the environment is that we almost exclusively act the latter, rather than the former. If we are going to continue to be consumers under the industrial-capitalist regime we are under for much longer, there must be a collective reasoning that in deriving wealth and value from natural capital and ecosystem services we must also responsibly steward the environment from which we derive such value.

The cornerstone literature of Fordham’s Environmental Studies program, Living in the Environment, provides insight into the inseparable link between the environment and economies.

The book defines natural capital as “natural resources and ecosystem services that keep humans and other species alive and that support human economies.” While it is easy to fathom the direct ways in which natural capital is derived: timber from forests, drinking water from reservoirs, and even real estate value from pristine parks, there are many ways in which we derive natural capital indirectly.

Many of us will never dive into the open ocean and see a coral reef up close, but as exemplified in The Value of the World’s Ecosystem Services and Natural Capital, many of us reap the abundance of natural capital its ecosystem makes possible. Coral reefs provide habitats and resources for a diverse population of aquatic life, providing for abundant fisheries that supply supermarkets, restaurants, and fish markets all over the world with seafood. More urgently, humanity’s failure to save these keystone ecosystems from acidification has ramifications not only for the local tourism industry, but also for the entire world’s food supply, and that of the remaining aquatic ecosystem.

For an example more close to home: Rhode Island derives immense economic value from the natural capital and ecosystem services provided to it by the Atlantic Ocean and Narragansett Bay which both support major pillars of the state’s economy. Fishing is an obvious one, as the New England states are famous for their seafood. Less obvious are the “unmarketed recreational activities,” [to which people flock to Rhode Island’s coast for: from sandy beaches to rocky shorelines people from all over the world come to Rhode Island in order to unwind and appreciate its natural beauty, simultaneously they also support the state’s economy, even if it is simply through inevitable tolls and beach admittance fees that help keep our natural landscapes clean and lower pollution levels.

As the climate crisis slowly reaches a crescendo in the Global North, many businesses big and small are switching to different variations of sustainable business models, whether it is GM committing to producing electric vehicles exclusively by 2035, or small coffee shops locally sourcing their food. The Wikipedia article on sustainable business provides a comprehensive glimpse into how the private sector can (and should) forge real change towards a sustainable future by reflecting environmental values in business policy.

I have experiences with a couple of different case studies in sustainable business. I worked at a local cafe in my community called the Nitro Bar which heavily emphasizes environmental values in its business practices. The cafe sources the lion's share of its foodstuffs from local farms, bakeries, and even other cafes in Rhode Island, the only thing it does not locally source are the coffee beans used to make their nitro cold brew, but that would be impossible since coffee cannot grow in Rhode Island. The Nitro Bar also packages some of their food products in reusable containers that customers can bring back to the store and use for other purchases, in addition to composting all of its food waste and shipping it to local farms for use.

Another case study (which also has to do with food) is Fordham’s Climate Impact Initiative Team calling for the university’s full divestment from its food supplier: Aramark. Although Fordham is not a business, for all practical purposes it operates as one in its pursuit of cutting costs wherever possible. Aramark provides cheap food to many large institutions, but the corporation faces controversy from every angle for its business practices, including its environmental policies that support industrial agriculture and produce mammoth amounts of waste.

In conclusion, I believe that industrial capitalism brings us to the current environmental juncture in which we find ourselves. I believe that it does not need to fall due to its coming environmental reckoning, however, to stand it must conduct a reckoning of its own that accounts for two things in particular. First, industrial capitalism needs to depart from the belief that the wealth it creates is due to capital itself. There would be no capital to spend, nothing to buy, and nothing to sell without the bounty of nature that it destroys in its name. I believe that if industrial capitalism clearly recognizes its reliance on natural capital and ecosystem services, and that without them much of its wealth would be lost, the second thing becomes inevitable: sustainable business. We are seeing paradigm shifts in businesses large and small already as the magnitude of the climate crisis becomes more and more pronounced. Today consumers value environmental responsibility in the business they patronize and their own consumer habits. Thrift stores and textile recycling is all the rage now, locally sourced food is more and more common in supermarkets and main streets across the United States, and our biggest auto manufacturer, General Motors, is committed to the exclusive manufacturing of electric vehicles by 2035. I believe that we are only seeing the first initial steps in our transition to a greener more environmentally friendly economy, and it comes as a result of a collective recognition that much must be done in our economic relationship with the environment in order to remedy the climate crisis.

Question: Will the transition to a green economy as it is going today be quick enough to effectively mediate the climate crisis?

WC: 1,034

0 notes

Text

Environmental Education Should be an Imperative for American Education

Before the pandemic, my typical route to school was as follows: On a humble side street, I’d awaken to the sounds of horns, engines, sirens, and screeches coming from Broadway and Bushwick Avenue. I look outside from my bedroom window, look at the sad, slumped trees barely staying alive in the sometimes harsh, industrial landscapes of northern Brooklyn. I’d walk under the subway overpass, up to my elevated train, and ride until I stopped at Broadway-Lafayette. From there, I transferred to another train in order to get to 59th St-Columbus Circle, a chaotic petri dish of some of the worst traffic in New York City. Sometimes I dared to cross the circle before class and enter Central Park, and when I did: aaaaaHHHHHH. All of a sudden, the hustle and bustle of New York, was given pause. Often, I found that on the days I gave myself a little extra time in the morning to go on a short stroll in Central Park, I felt more productive, accomplished, yet more calm, collected, and mindful.

Perhaps I was suffering from nature deficit disorder, the prominent of one of our readings for this week, entitled: Last Child in the Woods. Nature-deficit disorder is the theory that the spectacular retreat from the outdoors and into technology for education and entertainment has a wide range of regrettable consequences for our mental health, this is especially pronounced in young adults and children. In Last Child in the Woods, Richard Louv takes issue with what he calls today’s “wired generation,” alluding to the plethora of new technologies that have fallen into our laps and flooded our minds over the past two decades. The speed of which children in latch onto new technologies, with seldom anybody realizing the societal and psychological implications technological change has brought is truly astonishing.

From childhood to adulthood our brains need two things that we’ve lost during the pandemic: physical movement and novelty. In another reading for class this week: What is Education For? author David Orr contends that: “indoor classes create the illusion that learning only occurs inside four walls, isolated from what students and education institutions alike call “the real world.” Indeed, the science classes that I took from elementary school through to high school certainly amongst my most arduous courses, simply because the subject matter was made so redundant, so boring and soulless that I nearly made the conclusion that I had no desire to ever work in the realm of nature and the environment. What saved me from ridding myself of any environmental consciousness was the material I accumulated outside of the classroom interacting and mediating between the built and natural environments of where I live. One thing that I found particularly interesting about Orr’s piece is his proposition that ecological literacy should be an imperative requisite for all students, whether in lower or higher levels of education. I agree with his belief that no student should graduate from any educational institution without a minimal comprehension of the laws of thermodynamics, the basic principles of ecology, carrying capacity, energetics, least-cost, end-use analysis, how to live well in a place, limits of technology, appropriate scale, sustainable agriculture and forestry, steady-state economics, and environmental ethics. Orr lays bare that our education system produces environmentally illiterate adults. Today’s students inhabit a planet of which the consortium of top-down systems governing their everyday lives make environmental damage the default outcome in living day-to-day life. The lack of environmental education in the United States consequently makes environmental harm easier to tolerate and harder to see. I believe there are reasons to be hopeful, even after Orr’s laying into our deeply flawed education system. Americans are world champions at being sentimental over nature. If we make a concerted effort to improve the environmental literacy of our student populations, the population as a whole may better comprehend the various systems at play that degrade the environment and enstill the desire for a paradigm shift of our relationship with nature, and therefore, with each other, much as being an Environmental Studies major at Fordham University has taught me.

The overarching goal of education is ultimately to produce a well-rounded, self-governing citizenry that can propose, deliberate, and affect change in within their community. The concept of “environmental citizenship [:] the idea that each of us is an integral part of a larger ecosystem.” Combined with civic spirit, environmental citizenship encourages citizens to take their environmental concerns into their own hands, evoking the stewardship worldview. One’s departure from secondary education coincides with full enfranchisement as citizens within their community. Many high school seniors across the United States must complete a senior project or capstone which contributes to their community in some way. With the impending climate crisis that all communities face in one form or another, an integral part of environmental education could be the application of environmental literacy and skills in the “real world.” For example, after Superstorm Sandy devastated the Northeast Megalopolis, one senior from my local high school decided to focus on restoring dunes at a public beach to mitigate against future flooding. If environmental capstones were required of every student in the country, I have no doubt that there would be a paradigm shift as to how society views and treats the environment. Creating a generation of environmental stewards could lend a hand to establishing intergenerational justice, assuring that the environment is clean, safe, and well maintained for the enjoyment of future generations. Additionally, being that such a curriculum emphasizes bottom-up efforts–– it could also become a booster for environmental justice as students observe environmental harms and hazards present in their communities by which they themselves may be affected.