Photo

Business is business, in Białystok, and in Minsk, and a reputation is a reputation, even if you use a syringe and a sharp knife to get it. My Poland-set story Transaction is published in December 2017 in the Stoneboat Literary Journal.

4����

2 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

(via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2DJoAwMrSp4)

1 note

·

View note

Text

Competition Writing

I'm making an appearance on Chris Fielden's excellent blog on all things writing today. I give my take on story-aimed competitions, and share what I think is a methodical approach to a haphazard enterprise, and am also passing on some (hopefully) useful advice detected from the judges of the V S Pritchett Short Story Award - their honorable discretion had to be negotiated! - and sharing some rather shocking statistics on the long-and-shortlisting process. I discuss how I set about preparing my V S Pritchett runner-up story, Traffic, and supply an extract from it and a link to it, on the Unthank Books site. http://www.christopherfielden.com/short-stories/traffic-by-nick-sweeney.php

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

419 from the UN Sec Gen

Ha ha – had to happen: Just had a 419 scam mail from Ban Ki Moon:

UNITED NATIONS COMPENSATION UNIT IN CONJUNCTION WITH FEDERAL GOVERNMENT OF NIGERIA IN AFFILIATION WITH WORLD BANK.

ATTENTION BENEFICIARY,

Hope all is well with you and Your family?, you may not understand why this mail came to you. In regards to the recent meeting between the United Nations and the Present United States Government to restore the dignity and Economy of the Nations,Base on the Agreement with the World Bank Assistance to help and make the world a better… etc etc etc and signed off:

Making the world a better place,

Mr. Ban Ki-Moon Secretary(UNITED NATIONS).

Pastor REV,GEORGE NOYCE

Regrettably I had to correct his shocking written English and remind him that I’d told him not to bother me at work and to fuck off and pester Bongo from U2.

0 notes

Text

The Thin White Duck in search of a glass of water

The Thin White Duck is on Top of the Pops again, wondering if there is life on Mars. I imagine people under 50 are probably mystified by the idea, but back in the day a chart single might cost an astonishing 30p, so every month the Top of the Pops series brought out an LP - oh, I mean a *long-playing vinyl record* - with cover versions of all the number one tunes, done to sound as close to the originals as possible, and that would cost a bank-breaking 75p, but obviously much cheaper than buying all the originals. They did a pretty good job, in general; it's very difficult to recreate arrangements, and even more difficult to conjure up the feel of a studio that may have influenced the sound of any recording. In this version of Life on Mars, the strings are pretty much spot on, though the Bard's voice and Mick Ronson's guitar sound are impossible to replicate exactly. They include the ringing phone and the request for a glass of water in the tune's fading moments. If you liked the original, or listened to it as obsessively as I did at the time - I used to wonder not whether there was life on Mars but questions like who's ringing David when he's busy? Is it a Martian? Why was David thirsty? Why did he want water? Didn't he bring any Special Brew? Etc.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=n3on2vVAK_o&feature=youtu.be

0 notes

Text

Trick, Treat, or just Shite? All Hallows Marshmallows

When I was a kid we didn’t do Halloween in England. It was purely an American thing, a thing I read about in American comic books, and that was all, or so I thought till I went to live with my aunt in Dublin. They had Halloween there, for sure: it was Guy Fawkes Night, basically, but with Guy Fawkes happily absent from the proceedings, no bonfires, and with fireworks few and far between. I didn’t realise it till years later, but of course it’s because Guy Fawkes was a Catholic, and not just any old Catholic, but one who'd tried to blow up the Protestant king and government of England. They were hardly going to celebrate barbecuing him in Catholic Ireland.

I date Halloween in Britain to sometime in the 1990s. I was living abroad by 1990, and we didn’t have it then. When I got back in the late 90s, we did, for some reason – pure commercialism, I guess; it's all been imported and forced on us. A bit like the Corn Laws of 1833 et seq. I also think it has something to do with festivals, and how lots of people get the taste for dressing up funny and partying, with any excuse. And why not? I mean, one thing London really needs is yet more pissed people wandering around looking wacky. So now we have the virulent anti-Catholic cat-scaring whiz-bang of Guy Fawkes and the crazy dressing up of Halloween all together in the space of five days.

My wife is from Northern Ireland. She tells me that kids there did a thing they called Halloween Dunders; it involved knocking on people’s doors and legging it. I mean, we used to do that all the time in London, or, at least, anytime we were bored. We called it Knock Down Ginger, for some reason. I can’t see the point of Halloween Dunders – it’s all trick and no treat. They’re pretty hardcore in Ulster.

I forgot for years that I’d once taken part in Halloween, that year in Dublin when I was nine. I can’t remember what my costume was. I do remember that we went out in a gang, not accompanied by adultts, and that we ranged round the few

streets near where we lived, in Clontarf. Our local haunted house, called Simla Lodge, scary even in the daylight all year round, must have looked even more spooky that night. I also remember knocking at some old woman’s door, and she

handed over the goodies then asked, puzzled, “Who are you?” For reasons that escape me, I named some local kid. “You’re not him,” she said, and the old crone made a grab for my mask, unsuccessfully. I stepped back and left, and thought no more of it.

Later, probably years later, I thought she must have had a good idea of who I was. Everybody knew everybody, at least by sight, in Clontarf, and she must have known – as everybody else seemed to – that I was one of those pathetic brothers from London, who’d been sent over to my aunt’s to allow my dad to die in peace, albeit at great length, of cancer. Though I wasn’t sure of the last part, I think I was pretty sure that our presence in Dublin had at least something to do with our dad having been in bed at home more or less permanently, for some time. I’d hardly been in Dublin long enough to acquire a Dub accent. So the nosey old biddy was just being a nosey old biddy; the things some people expect in return for a hard toffee – those yellow-wrapped ones from Quality Street that nobody likes – and a miserable apple…

A few years ago my friend Jerry, who’s from Pennsylvania, was living in London, up near Belsize Park which, if you don’t know it, is one of the wannabe posh areas leading up to truly posh Hampstead. The evening before Halloween one of his neighbours, a big-haired wannabe posh woman, appeared at his door, clutching a big bag. She informed him that, the next evening, her children and their friends would be calling to do trick or treat, and that he was to be so kaind as to present them with the small bag of goodies she extracted from the big bag, and passed over to him. Jerry took the bag. It slipped his mind that he wasn’t going to be home the next evening. Being a bodybuilder and a growing boy, he probably scoffed half the goodies before he even got back to the living room.

We both thought it was kind of laughable, a little pathetic, in fact. As a kid, Jerry and his friends went and did their trick-or-treating round their neighbourhoods, just as I did it that one Halloween in Dublin. Scary stuff happened, sort of – isn’t it meant to? There was probably the weirdo neighbour who wore socks and sandals, from whose place strange noises could be discerned once the ring of the doorbell had subsided. Was he playing basketball with a kid’s head? Was he behind the door with an axe? Or maybe just crouching there hoping those damn kids would believe he was out, and go away and bother somebody else? There were the usual rumours: kids taken to hospital with razorblades-stuck-in-apples wounds, kids frothing at the mouth and out of their minds on MDMA and acid – like any self-disrespecting acid-head was going to just give it away like that…

I believe there wasn’t ever too much of that kind of thing. Maybe it was all part of the Halloween myth – after all, kids are more likely to meet fucked-up people who like harming children than they are to happen across vampires, werewolves and zombies. But in Jerry’s day, and my single night, the point was that kids went out, with their friends, and did it. The scary stories gave us an idea that there was at least some risk involved – I mean, Halloween is supposed to be scary, remember? So we thought the visit from Jerry’s neighbour was kind of ludicrous; where was the spontaneity in that? And, we thought, later, where was the opportunity for a trick?

I’ve since had a similar visit from my own next-door neighbour. In 2008, her kids had called at the door going, “Trick or treat,” in bored monotones. Not doing Halloween at all – I think I thought of it in Britain as solely to do with adults partying and looking ridiculous – I was slightly puzzled, and had to get them to repeat it. If it looked to them like I’d never heard the three words, it seemed to me that they didn’t even know what they meant. There were five kids, I think, gathered somewhat awkwardly on our top step. Out on the pavement near our gate stood a gaggle of parents. Not being into Halloween, and not being the kind of household that keeps things like crisps, biscuits, cakes or stuff like that (they have a short, doomed existence in our house) I had nothing to offer. I didn’t think they’d have liked a Ryvita, some leftover pasta or a pickled walnut. Fortunately for all of us, the poor little mites didn’t seem to know how to trick: they came expecting treats only, with no contingency plan. I sometimes think all middle-ish-class kids expect to be treated, all the time, without having to do anything for it. It was a forlorn sight: kids, supposedly out to have some fun, dressed in costumes from the pound shop, mouthing words they didn’t understand at puzzled strangers, and their mums and dads a few yards away holding a health-and-safety committee. Really, where IS the fun in that? It was crap.

I’m not saying kids should be exposed to stranger danger on Halloween or any other night. If I had kids, I really wouldn't want them wandering round knocking on people’s doors. I’d still be worried about razor blade apples and soft drinks with MDMA and rat poison in them, just a bit, despite the urban legend nature of those stories, and about Gary Glitter answering the door. On the other hand, children should be able to have a proper childhood, and to be able to believe in imaginary things that grab them, enthuse them, scare them, even, a bit. What’s the answer? I don’t know that. But their Halloween experience ought to be better than the one I saw.

So in 2009 my neighbour came the day before, with the treats supply. I chickened out of giving her a condensed version of what I write above; she was just doing what she thought best, trying in her own way to make something of Halloween for her kids and their friends. I told her, truthfully, that I thought we might be out, but she kindly gave us the treats anyway, said it was no big deal, and that we could give them to somebody else if we weren’t in. I wasn’t at home, as it turned out. My wife duly handed over the trickless treats.

My neighbour didn’t come last year, and nor did the kids. Maybe they’ve grown out of it, or maybe have tumbled, basically, that it’s just crap.

0 notes

Text

Laikonik Express - the missspelling of names: Ellis Island

Once everybody was seated, Jack’s mom was demanding to be told about Don’s name. He went into his raconteur part and told the story of how his grandpa on his dad’s side made the damp crossing of the pond from Gdynia to New York way back in ragtime. He had the Christian name of Dariusz, pronounced dar-ee-oosh, and the family name of Pszczynski, which went pish-chins-kee, both of which just looked fearsome and barbaric written down. The Ellis Island officials had as little success as Kennedy in getting their tongues around the names, and wanted to knock off for the day and go home, so they just put his first name down on his papers, and, unhappy too with the s and z combination, chopped off the z. It was a familiar tale to them all, but they found themselves caught up in it all the same. Laikonik Express p135

0 notes

Photo

If Kennedy was remembering rightly, La Clemenza di Tito was one of those operas that, as far as a schleb like he was concerned, got opera a bad name. It featured a few bona fide arias, but it was mostly just people warbling phrases over an annoying keyboard. Kennedy did not mention this to Don; a harpsichord was tinkling an alarm to remind him that in Istanbul Don was always dragging people off to the opera, then grizzling the whole time about it boring him shitless. Kennedy lied, and said, ‘I saw that one already.’

‘You did?’ Don did not look too disappointed. ‘Does it work?’

‘I hesitate to recommend it, man. A good tune or two, but…’ It bugged Kennedy, just in passing, that he could not remember any of the arias from Tito. ‘You know, it’s like eating a seafood salad, see, and you only got one mussel in it.’

‘Oh. Right.’ Don looked wistful, and pained at the same time. ‘I ate that salad. Spare me another.’ Laikonik Express p47

One of those bona fide arias from Mozart's Roman opera La Clemenza di Tito (according to this schleb): 'Torna di Tito al lato', which I thought for years meant 'Go and get Tito a milkshake.' See sopranos Maria Höglind and Lani Poulson rather unconvincingly playing chaps here - you just can't get the castrati these days...

0 notes

Photo

A man on a horse… or more accurately a horse on a man. This is the Lajkonik, a symbol of the city of Krakow. They named the Lajkonik Express train after him.

Not the greatest or clearest of photos, but it's of a folk-dancing troupe in the Rynek, the main square, in Kraków, and at its centre is the figure of the Lajkonik. I took this photo on my first trip to Poland, in the summer of 1992, years before I took my regular journeys on the Lajkonik Express, and before I thought of writing a book with that same title.

The Lajkonik represents a Tatar, a bearded, turbanned man from the east, perched on a horse. The Tatars are a people that originated in central Asia, and have strong Islamic traditions. You can read a summary about them here, but basically they were part of Genghis Khan’s hordes who devastated various parts of Europe from the 13thC on. The word Tatar began to be applied to any people from the east who had designs on your cities, goods and chattels. There are Tatar communities across the former Soviet Union, and in parts of Europe such as Poland and Turkey, and even in America.

Various stories are attached to the Lajkonik in Krakow. The figure may represent the time the Krakovians killed a a Tatar khan, or leader, and dressed in his clothes to show their victory and rub it in. There is also a story that some locals dressed up as Tatars inside the city walls to play a joke on their fellow city dwellers and make them think they’d been invaded – I honestly cannot see this going down very well. Whatever its origins, the Lajkonik stands as a sort of ‘bogeyman from the east’ figure – fear of alien cultures; funny, but this is beginning to sound familiar. The bogeyman has been de-bogeyed to a certain extent, rendered into a good luck symbol, the Lajkonik name being given to hotels, foodstuffs, dancing troupes, and at least one train.

0 notes

Link

'Under bare Ben Bulben's head

Cast a cold eye

On life, on death.

Horseman, pass by!’

from Under Ben Bulben by W.B Yeats

Next stop Sligo, in the shadow of Ben Bulben , imposing like an Indian totem, a sacred mountain and Yeats’ other Muse. Yeats was intimidated by beauty...

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

It took the people of Yorkshire to show the Tour de France how it was done this year. The race never quite recovered its momentum after leaving them behind to get back to France. The early dramas came partly from stupidity, with Manxman Mark Cavendish out of the race on the first day when he head-barged another rider, hit the ground and couldn’t get up unaided; past winner Alberto Contador decided to pull an energy bar out of his pocket while doing 80KPH downhill – I mean, what could go wrong there, except of course the crash that sent him to hospital? Defending champ Chris Froome crashed out early too, thankfully through no fault of his own, and his absence could have stopped it being a bit of a snooze… except that Italian grand tour contender Vincenzo Nibali took over that job. The 2014 Tour was notable for the resurgence of the French; French riders battled it out to win second and third places, the first Frenchmen to reach the top three since 1984. It would be fantastic to see them reclaim their event.

Naturally, I don’t only watch cycling to see winners wearing various coloured jumpers and holding up bunches of flowers and kissing girls. Every sport features beautiful ways to win… well, not judo, possibly… but there are also beautiful ways to lose, and such moments often leave more of an imprint behind them than even the most spectacular win. Some of these moments can look stage-managed and cheesy, such as leading doper Bjarne Riis ‘honouring’ the previous winner Miguel Indurain when the 1996 race wiggled over to Spain to go through the latter’s home town, in the full expectation that he would be leader; there was also a young Lance Armstrong’s ‘tribute’ to team mate Fabio Casartelli as the Texan pointed to the sky when he won a stage a few days after Casartelli’s death during the 1995 Tour (a feat of formaggio repeated 6 years later by an older Armstrong). There was the moment when deadly same-team rivals Greg Lemond and Bernard Hinault crossed the line with their hands not round each other’s throats but clasped, in the 1986 Tour.

My favourite by far of these moments of loss featured Australian Cadel Evans in the 2010 Tour. It’s safe to say that Cadel had been trying for a few years to win a grand tour; he was a clear contender, with placings at 8th, 4th and 2nd, but by the end of the noughties was getting the reputation of being a nearly-man. The general consensus is that he was often edged out of the top place by dopers. Maybe this contributed to his reputation as a bit of a grumpy bastard in the face of questions from the press and fans about his performances. I kind of don’t blame him; he was never able to give any accurate answers that wouldn’t have landed him in hot water with the entire sport.

In the 2010 Tour de France, Cadel was World Champion, but finally got to give the rainbow stripes of the WC jersey a rest to wear the yellow jersey – given to the race leader – on stage 9. If you’re familiar with how bike racing works, you’ll know that the jersey, and the race, isn’t won till the last day. Until then the wearer of the jersey has to use his team to defend him against attacks by other contenders and their teams; they will seek any weakness – a fall, an injury, even to a team member, a loss of tempo or concentration, a sudden change from good weather to bad, a crash in the main group that may hold up anybody behind it – and exploit it. It’s a fraught business. Halfway up the last climb of a five-climb day, the fearsome Col de la Madeleine, two teams, Saxo Bank and Astana, put pressure on Cadel’s BMC team, and one by one his team mates dropped away, and then so did he, knowing he was going to lose the jersey that day, and what was more, be so behind that he’d never be able to regain the time he’d lost.

Cadel also had a bit of a secret: he’d fractured his elbow two days before. He didn’t mention it, even to his own team, just didn’t want it to become common knowledge. I’m not sure how wise this is, but there are numerous instances of riders carrying on with broken bones, at least for a while. Wise or not, it puts certain pro footballers into perspective as they get a tap on the ankle and roll around in agony.

Cadel had one team mate left. 26 year-old Italian Mauro Santambrogio rode in front of Cadel, sheltered him from the wind as much as he could. At that time he was an established domestique, or team helper, having ridden for several teams. In the footage of stage 9, Santambrogio has a fixed, determined expression, composed– and not the teeth-gritting ‘race face’ of riders going all out. He looks serene, almost angelic.

They knew Cadel had lost, but they rode anyway. At the end of the stage, Cadel put his head on Santambrogio’s shoulder and sobbed. Santambrogio put an arm around his team leader’s shoulder. It’s a sad picture, but a great one all the same. Cadel didn’t ride his customised yellow bike again, and had to revert to his rainbow jersey of World Champion – which is, after all, not so bad – and, broken elbow and all, he stayed in the Tour, and finished a respectable 26th.

Cadel finally won his Tour de France in 2011, and what a great, and well-deserved, win that was. He’s had a few moments since then – even wore the leader’s pink jersey in the 2014 Giro d’Italia for a few days, but really, he stopped being hungry enough to win a grand tour after 2011. He is a fine sportsman and a great man in his personal life, I think, with his support of Tibet, and his comparison of its people to that of Native Australians, plus his donations to charities. I think cycling will be a poorer sport without him when he retires.

Santambrogio’s story hasn’t ended quite so well. He wasn’t with BMC by the time Cadel won his Tour, had moved on to the near-enough all-Italian Vini Fantini team. He was making waves in the 2013 Giro d’Italia. He even won a mountaintop stage, flouroescent yellow in his team kit against the equally glaring backdrop of white snow. After the race, which saw the ejection of his team leader Danilo di Luca for doping, Santambrogio failed a test for the performance booster EPO – not the first test he’d failed in his career – and since then he hasn’t got back on a bike as a pro, and, I fear, he never will, and fear too that, even if he does, he’ll never have a finest hour than the day he tried to help Cadel limit his losses in the 2010 Tour de France.

#cadel evans#maurosantambrogio#tourdefrance#2010#winners#losers#cycling#couple#mountains#race#bike race

0 notes

Photo

I first went to live in Poland in 1993. I got a teaching job in a private language school in the Silesian town of Gliwice, in the south west of Poland. I’d been at a loose end in London for a few months, having come back from living in Istanbul in August the previous year. I’d been intending to do an MA in Linguistics in Birmingham, but for various reasons the funding had fallen through. My first wife was doing post-grad teacher training in London, and we were living with her parents. Work didn’t look like it was going to happen for me in London, though in fact I didn’t try that hard: working as an EFL teacher in a private language school is okay if you’re abroad somewhere, but doing it in London just seemed ridiculous.

I got an interview with a bloke who ran a language school in Ljubljana, and was accepted for a job, but there was something about him I didn’t like. From his somewhat evasive answers to questions I asked about the working conditions, hours and pay, he seemed like one of those workaholic types who expected the same from me, on little pay, and, in addition, other things he said suggested that he was recruiting for his social life. I may have been wrong about that. I kind of regret not going to Ljubljana: it was a happening place, it seemed, after the ten-day war it fought to become independent from Yugoslavia, and times were surely exciting there. I didn’t get to Ljubljana until 2009. Instead I saw another ad in the Education supplement of the Guardian newspaper for a school in Gliwice. I answered it, had an interview in an empty room in the then empty-all-over CanaryWharf, and decided I’d take the job, and set off for Poland two days later. That was one cool thing about EFL teaching: see an ad on Tuesday, have an interview on Thursday, fly somewhere else on Saturday and, after a day or two to settle in, you’re living a different life by the following Monday.

It started snowing in Gliwice the week I got there in early January. It didn’t stop till April. When people here in London say, “I love the snow,” I don’t reply, as it would be a sort of snotty-sounding, “You weren’t in Gliwice that winter.”

The school was a bit crap, run, as is often the case in EFL, by idiots, but the students were okay, and I mostly managed to put on a good front and get on with it for them. I’m pretty good at getting on with work and pretending I love it, then switching it off and forgetting it for the more important things in life. After a bit of messing about from the people who ran the school, I was finally given a small flat overlooking what turned out, when the snow finally melted, a graveyard. It’s great to have quiet neighbours.

All of us teachers at the school griped about Gliwice at times. We changed the opening lines of Crowded House’s tune Whispers and Moans to Dull, dull grey, the colours of Gliwice… and sang it with some gusto. But in fact that was mean of us. Gliwice is a magical little town, with a mysterious vibe. There is an old rynek, or market place, at its centre, its buildings not exactly graceful, but intriguing all the same. There was a bit of everything in Gliwice: the square and its arches, a gothic-looking post office, sturdy fortress-like churches in black and brown brick, a lively railway station full of the usual shady characters, and babushkas in the ticket offices who were awkward with us if we got the grammar case wrong when buying tickets, especially if we were in a hurry. There were cafés and bars that looked as if they’d been designed by architects who really hated people having any leisure time, but were all the same friendly, and cheap. There were shops selling only red plastic kitchen equipment. There were tall communist-era housing blocks with Wendy houses painted on them, and you made sure to walk equidistant between them, as balconies and other bits were said to fall off them regularly. (A few people assured us that this story was a wind-up, and yet there were worryingly matching chunks of masonry on the ground by some of the blocks.) There are shrines in glass cases that led to the small industrial areas that ring the town, water towers that looked like Byzantine domes, and the brown brick of classic pre-war German Silesian housing, known as familoki or familie lokat, and the forlorn-looking ground of the Piast football club – the season takes a break for the snow – whose fans were certainly, er, dedicated. There is the Kłodnice, a black, polluted river, a market full of Eastern Bloc goods and characters, soot-faced miners with horses and carts selling excess coal, Gypsy women and babies routinely dumped on the town from a lorry on regular days of the week to get out there and make a living, grannies in formal clothes but with moonboots, and middle-aged housewives who insisted on wearing stiletto heels, even in the snow. There is also the tallest wooden structure in the world, the tower at the radio station. This is where the Nazis attempted to start the Second World War in August, 1939: for Gliwice was once Gleiwitz, and was once in Germany, and the Nazis came up with a ridiculous fight-starting ruse, the concoction of a ludicrous story about the Polish army attacking the radio station. It didn’t work, though that didn’t matter to the Nazis, who unfortunately didn’t let such a thing set them back for long.

I missed my wife – of course I did. She came over to spend a couple of weeks with me at Easter. She was on holiday from her course, but had plenty of work to get on with for it when I was at work. Along with the rest of the country, we finally had the long Easter weekend off together.

Poland is, of course, a Catholic country, and Easter is much more important there than it is in secular countries. Lots of businesses close, as people either go to see relatives, or have them staying. What many of them do is visit churches with small baskets of eggs, to have them blessed by priests. It looks slightly comic, seeing all kinds of people, but mainly old women or younger women with children, walk through the street towards the churches with their eggs. Some have a tiny plain basket, others a larger, flasher, beribboned one, maybe with an elaborately-patterned szmata, or cloth, lining it. Some people have their baskets packed with stuff, and we joked that they were bringing their entirely weekly shop to be blessed. This scene was part of the backdrop of Easter in Poland, and we saw a lot of it, partly because that weekend we set off on a journey that took us to lots of smallish, quiet towns whose churches were the main focus.

“Bless my eggs!” we said, did it as Kenneth Williams, Hattie Jacques, made it into an expression from a Carry On film that had never been made – Carry On Easter, Carry On Poland, Carry On Catholics.

We’d got the train across the country to Lublin in the south east, and were staying in its Dom Asystentki, or student hostel, which, it being the Easter hols, was absolutely empty. It was kind of dull and kind of cold, kind of dimly lit, and kind of grim, but we didn’t care. We weren’t there to lie around in the hotel. With Lublin as a base, we ventured to some of the smaller towns in the area. I also achieved a tiny and ridiculous ambition to send postcards to my relatives in Dublin that said, somewhere on them, ‘from Lublin to Dublin’, and wondered, as ever, if the two cities had been twinned, resolving to find out. (I looked it up today, 21 years later: they’re not.)

On Easter Sunday we had a three-hour coach journey along the eastern border to a town called Siemiatycze. Some of my wife’s family had come from there. Most of them had been murdered in the Treblinka death camp during the Second World War, but there were a few traces of them: her great great uncle had built the synagogue there, and the street his doomed descendants had lived in, ulica Szkolna, or School Street, was still there, though we weren’t sure whether their houses were still standing. There were also apparently the remnants of a small Jewish graveyard.

The journey was grindingly slow. Coach journeys could be up to 45 minutes slower than the advertised journey time, depending on whether the driver was a smoker or not; if he was, then there were plenty of stops for indulging in the noxious weed. This was one of those, with people shuffling out into a misty day to inhale either fresh air or tobacco. Most of the people on the bus were visiting relatives for Easter, and had luggage full of pungent salamis, cheese and children – it wasn’t quite steerage class peasants with chickens from a Kusturica film, but seemed surreally close to it at times. Many of the men on the journey were pissed as farts – this was at nine in the morning – starting off the celebrations early, and their breath was alarmingly toxic from a few feet away. And yet, this is not a moan. It was eastern Poland, and full of the old habits of a country that was, for a few years after 1989, divided to all intents and purposes, the east not getting the much talked-about economic trickle-over effect of the new capitalism: we’d chosen to go there, after all. Once we were moving again, the movement began to hypnotise me a little, and maybe I just imagined seeing the towers built on the eastern border, and a giant statue of a soldier, or was it an astronaut, left over from communist times. I didn’t imagine the fumes, the excited high-pitched conversation and pisshead laughter, or the tinny music on the driver’s radio, the people getting on and off at various spots along the way, the goodbyes, promises to be friends for life with other drinking strangers, waves full of affection that was genuine, if only for those drunken holiday moments that had all the possibilities of freedom and celebration in them.

Siemiatycze was a compact little town under a layer of fine mist. The crows made noise in the bare trees above us, their cawing rhythmic and insistent. I always imagine crows actually saying something including an insult that starts with c and ends in t – as if they were berating us for coming all that way to a town in which very few places except the churches were open. The people headed in and out of them with their baskets, and that part of it was all as it had been in Warsaw, Lublin, Częstochowa. We watched them for a while, and made a search for a bar or café – we were hungry by then, having got up at sevenish – but none were open. We had to go back to the decrepit bus station, even more forlorn looking than these places usually are, to grab a coffee and a sandwich, and then resume our quest in the increasingly deserted streets of the town. We found the onetime shul, or synagogue, a building that was solid and functional, rather than elegant, painted yellow and, these days, serving time as a community centre; as with most towns in Poland, there was no Jewish community left to use it as a synagogue. Ulica Szkolna was similarly unremarkable, but we weren’t disappointed, as we hadn’t come to see great architecture or anything of great beauty or intrinsic interest. It was my ex’s commune and connection with a part of her past, that was all, and it was important to us, and to nobody else. We didn’t find the graveyard. Siemiatycze, though small, was bigger than we’d thought, and there was one bus back to Lublin that day – we really had to be on it.

We were back at the bus station early, then. Another drecky kawa turecka – the Polish version of Turkish coffee, which was, er, a work in progress – from the station café, and between us a rock-hard roll with sweaty cheese, the only one left.

My ex went to the loo, and was ages. A man and his two small sons came into the waiting room, and settled down on the bench near me, and near the tiny heater. We caught each other’s eyes, and he gave me a rather down-sounding greeting, let out a big sigh, held his hand palm up as if to say look at this place – what? Huh? Though in fact I was glad of it; it had turned very nippy outside.

He didn’t speak much English, and my Polish was pretty basic. He pointed to my wedding ring, worn on the third finger of my left hand, and then pointed to his own, as if in commiseration. I thought he was being a long-suffering henpecked hubby from Carry On Poland, and was prepared to be uncritical but non-committal. In fact, it was genuine commiseration. He said to me, “Your wife is dead?” I frowned, and said, “She seemed quite chipper a few minutes ago.” Despite the jokey tone, I was a bit puzzled, and quite relieved when I saw her come back into the interior from the loo, swinging its key to hand it back to the babushka in charge of it. I introduced her when she got back, and the man nodded. He too was relieved, and anxious to explain to me that in eastern Poland the wedding ring was worn on the right hand, unless you’d been widowed, in which case you put it, like his, on the left hand. It was my turn to make commiserations, though it pained me and pissed me off that I couldn’t understand how his wife had died – that none of the words he used in explanation were familiar to me, none of the gestures – only that it had been the year before, and that he was taking the children to stay with his sister for the remainder of the Easter break.

The coach back to Lublin was near-enough empty. We chatted and gestured to the man and his two well-behaved boys, about nothing much, until he got off at some roadside in the middle of nowhere. The driver wasn’t a smoker, and the journey passed quickly enough. I forget exactly where we went that Easter Sunday night in Lublin. We were knackered, and not hungry. We went for a drink at a place that chucked us out as it was closing early, and then may have had an early night.

Easter Monday morning we woke early. We were starving by then. We went out in search of breakfast. Not one single place was open. We covered a lot of Lublin in our search. We got it: most places were shut because it was Easter Monday, okay, so we just had to find the places that were open. We’d appreciate our breakfast even more, then. We found nowhere. Even the lowliest burger shack was shut, the tiniest kiosk. We spotted people a long long way up a road making a small queue at a kiosk, and yelled with joy, but then it turned out to be a flower stall. Flower stalls were the only thing open. You couldn't eat flowers, I was fairly sure, though I was hungry enough to do so by then. All the cafés, all the bars, all the restaurants, all the hotels, shut for the day.

What about the cinema? We’d been there on the Saturday night to see, I think, Of Mice and Men. At least we could buy a bag of crisps or something – but no, shut. We finally went back the grim room we’d decided we weren’t going to spend much time in, and read our books, listened to music from my Walkman through its little speakers, dozed, looked out the window. My ex found a Mars Bar in her bag. She’d bought it the week before, for a train journey, but had forgotten about it. That was what we ate, used a little penknife to slice it. It filled a gap. It wasn’t a three-course meal, nor even a hard sandwich with sweaty cheese – I’d have killed for another of them – nor an Easter egg, but it did its best. We had an early night, got up the next day to begin our trip back to Gliwice, but not before we went out and had the biggest breakfast we’d ever had.

0 notes

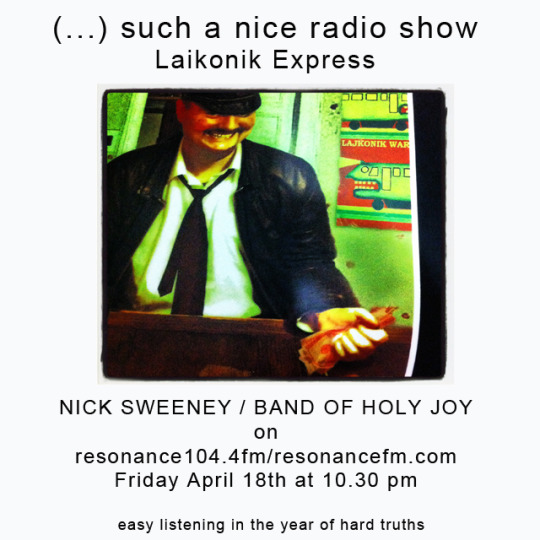

Photo

VERY EXCITED to be on London's arts radio station Resonance 104.4FM tomorrow night at 10.30 in a show incorporating my novel of friendship, Poland, snow, trains and vodka, Laikonik Express. In collaboration with Johny Brown and The Band Of Holy Joy, we’ll be exploring some of the music associated with the book, or prompted by it, implied, inferred, or just made up on the spot. I’ll be reading some short extracts, and we’ll make a soundscape or two out of it all. Tune in to Resonance 104.4 at 10.30 PM Friday for Johny Brown’s much-loved Such a Nice Radio Show.

0 notes

Photo

Laikonik Express on the air. More to come soon. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-Fh9se-j-SY

0 notes

Photo

unknown architect - lloyds building, viale mussolini, asmara, 1938

166 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Andabatae - my short Roman tragedy

'Anton felt heavy-lidded, but knew that if he closed his eyes terrible angels would scratch holes in the membranes at the back of them. He hurried across the estate, arrested by the thought of what had happened to the bright-eyed kid who came to Rome to study the city’s history and culture. He had a dim memory of that kid’s face, tried to place it, then was astonished to see it blinking gauntly at him for a second from the vitrine by the metro.'

What is a boy to do when his friends go to ruin and his mind compels him to follow them? Rome, sometime in the 1990s, and Anton sees new revelations in the ancient stones, ancient visions in crowded clubs and lonely bathrooms. No heroes, no heroines, just heroin.

Online in Ian Chung's marvellous Eunoia Review in August.

0 notes