Text

Overview

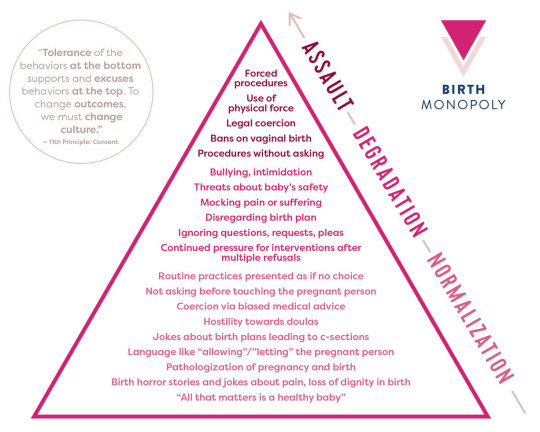

Worldwide, women are suffering from reproductive health inequities which have persisted for decades. In an over medicalized system dominated by physicians, birthing women are frequently exposed to many non-consensual and unnecessary procedures which have no scientific backing. Despite being recognized by the World Health Organization and other institutions, women continue to be excluded from participating in the birthing process and are subjected to coercive and abusive practices throughout their labor. Obstetric violence has become an invisible and naturalized form of violence, and poses a serious violation of human rights. It is necessary to acknowledge the flaws which plague maternity care and to emphasize the lack of autonomy of laboring women.

In recent years, growing trends in the excessive use of medical interventions during childbirth, along with an unsettling presence of abusive and disrespectful practices towards pregnant and birthing individuals, have drawn attention to a global issue concerning human rights and childbirth. Though not yet fully recognized, the term “obstetric violence” describes the systematic problem of institutionalized, gender-based violence that many women are subjected to throughout the processes of gestation, delivery, puerperium, and the reproductive cycle. Due to the high number of cesarean sections performed and an increase in complications from pregnancy or childbirth, women in the United States have one of the highest rates of maternal mortality. This mistreatment of women and birthing people in the childbirth setting has become normalized as routine care, disproportionately impacting women of color, indigenous women, members of the LGBTQ+ community, and other marginalized communities around the world. As with many other healthcare inequities, obstetric violence is an issue which intersects with social class, race, ethnicity, and gender. For this reason, it is important to view this topic under a sociological lens.

My interest in pregnancy and female reproductive care is what drew me to research the issue of obstetric violence. For many years, I had considered pursuing a career in obstetrics and gynecology, and have recently shifted my focus to midwifery. My intention with this career path is to provide comfort, security, and empowerment to women in an area where they are often perceived and treated as inferior. In the future, it is believed that adopting human rights-based constitutions and bodies of law that address obstetric violence would aid in solving the issue. The frequent occurrence of negative obstetric experiences indicates a need to transform perinatal care provision which requires a collective effort from all those involved.

0 notes

Text

Violation of Human Rights

Obstetric violence is a violation to women’s human rights of “non-discrimination, liberty and security of the person, reproductive health and autonomy, and freedom from cruel, inhuman, and degrading treatment” (Diaz-Tello 2016:57). Women experience mistreatment in the forms of physical abuse, sexual abuse, verbal abuse, stigma, and discrimination where a failure to meet professional standards of care allows for potential harms and poor affinity between women and practitioners (Logan et al. 2022; Lokugamage and Pathberiya 2017). Since 2006, Latin America has recognized obstetric violence as a form of gender-based violence as part of the Organic Law on the Right of Women to a Life Free of Violence. This law recognizes obstetric violence as the appropriation of the female body and reproductive processes by health professionals (Jardim and Modena 2018:7). In these situations, women are deprived of their status as citizens with rights under the law.

Increasing concern surrounding the serious public health problem has required involvement from the World Health Organization (WHO). The WHO recognizes obstetric violence as happening in “the hospital setting or in any public or private setting where acts on the female body or her sexuality can be established in a direct or indirect way” (Jardim and Modena 2018:7). Women are assisted in a violent manner and experience situations of mistreatment, disrespect, abuse, negligence, and violations to human rights by health professionals during the birthing process (Jardim and Modena 2018:2). The WHO has typified forms of obstetric violence into five categories (Jardim and Modena 2018:8):

Routine and unnecessary interventions and medicalization;

Verbal abuse, humiliation, or physical aggression;

Lack of resources and inadequate facilities;

Practices performed by residents and professionals without the woman’s permission after providing her comprehensive, truthful, and sufficient information

Discrimination on cultural, economic, religious, and ethnic grounds

0 notes

Text

“The World Health Organization (WHO) confirms that caesarean section rates higher than 10% are not associated with lower maternal and newborn mortality on a population level.”

(Sadler et al. 2016:49)

0 notes

Text

Abusive and Coercive Practices

In many instances of obstetric violence, it is common for women to experience threats to the custody of their children, to their right to due process of law, and to their bodily integrity (Diaz-Tello 2016:57). They are harassed by medical professionals who insist on obtaining their consent to unjustified medical procedures and surgeries, including cesarean sections, episiotomies, artificial rupture of membranes, prophylactic intravenous medications, epidural blocks, vaginal examinations, and fetal monitoring. Under extreme stress and fear of experiencing further or potentially worsened abuses, many women comply with the demands. As a result, survivors of obstetric violence often suffer from physical, psychological and emotional harms.

The intense medicalization of the female body has made the birthing process an excruciating, terrifying, mechanical, and intimidating experience. Within healthcare facilities, women are receiving care under factory line conditions. Half-naked women are left in the presence of strangers or alone in unfriendly settings, in positions of total submission with open and raised legs in stirrups, and their genital organs exposed (Jardim and Modena 2018; Lokugamage and Pathberiya 2017). Further, acts that constitute obstetric violence include the “untimely and ineffective attention to obstetric emergencies; forcing the woman to give birth in a supine position when the necessary means to perform a vertical delivery are available; impeding early attachment of the child with his/her mother without a medical cause; altering the natural process of low-risk labour and birth by using augmentation techniques, and performing cesarean sections when natural childbirth is possible, without obtaining the voluntary, expressed, and informed consent of the woman” (Sadler et al. 2016:50). Many women are frequently denied the presence of a companion of their choice, receive little to no information about various procedures performed during their care, are subjected to routine and repetitive painful vaginal examinations without justification, are deprived of their right to food or walking, must undergo frequent use oxytocin to accelerate labor, and suffer unconsented procedures such as cesarean surgeries[1], episiotomies[2], artificial rupture of membranes, prophylactic intravenous medications, and fundal pressure[3] (Jardim and Modena 2018; Logan et al. 2022). Pregnant women’s rights are consistently violated in relation to physical integrity, self-determination, privacy, family life, and spiritual freedom.

[1] Cesarean section: a surgical operation for delivering a child by cutting through the wall of the mother’s abdomen

[2] Episiotomy: a surgical cut that is made at the opening of the vagina during childbirth, thought to aid a difficult delivery and prevent the rupture of tissues

[3] Fundal pressure: an aggressive and painful procedure in which a woman’s body is heavily pushed upon to move the baby

0 notes

Text

Though commonly used in delivery rooms, there is no reliable evidence to suggest fundal pressure is effective in progressing labor. In certain situations, fundal pressure can contribute to complications and injury to the baby.

0 notes

Text

Failed Medical Model

Comprehensive care[1], which prioritizes the individual patient’s goals and needs, is being replaced by complex technologies aimed at treating the female body as though gestation is not a physiological event of life, but one that requires excessive control and management (Jardim and Modena 2018:2). Following the stereotype that women’s knowledge, and that of birthing women’s in particular, is inferior and unreliable due to their more emotional and irrational nature, technology and medical staff become the most reliable sources of knowledge in the labor room (Campero et al. 1998; Cohen Shabot 2021; Diaz-Tello 2016; Sadler et al. 2016).The birthing process is thus transformed into a professional-centered act, where physicians and other medical staff, rather than pregnant women, are entrusted with the decision-making authority (Cohen Shabot 2021; Diaz-Tello 2016; Jardim and Modena 2018). Women are “disenfranchised as a group and suffer from testimonial injustice, their knowledge generally considered problematic or less authoritative, rendering them vulnerable to many other, additional kinds of injustices” (Cohen Shabot 2021:639). The dismissal of women’s overall agency and epistemic power within childbirth serves to justify threats and coercions associated with obstetric violence.

The medicalized model of childbirth emphasizes the idea that professional medical staff are the most qualified to determine what is best for the woman and her child. “When we take medical authority as given, and medical knowledge as indisputable - the only right knowledge for managing childbirth - a woman’s knowledge of her birthing body is automatically dismissed” (Cohen Shabot 2021:646). However, doctors frequently lack knowledge of non-medicalized physiological birth, and are less acquainted with the perspective of birth as a normal physiological process (Cohen Shabot 2021:646). This epistemic injustice further contributes to the most significant damages produced by the medicalization of childbirth. Support for birthing consciousness, which is associated with focused attention, calmness, better pain management, less fear and anxiety is crucial to physiological birth, yet missing from the medicalized model of childbirth (Cohen Shabot 2021:649).

[1] Comprehensive care: care that is aligned with the patient’s expressed goals of care and healthcare needs; considers the impact of the patient’s health issues on their life and wellbeing, and is clinically appropriate

0 notes

Text

Gender Stereotyping

Birthing women are mistakenly considered “riskily vulnerable, out of control, and incapable of accountability or good decision-making, to an even greater degree than the ill” (Cohen Shabot 2021:637). Women are dominated and disciplined through “invisible” violence, a type of violence which has no clear intention or necessarily includes physical harm, and can be difficult to recognize even for its victims (Cohen Shabot 2021:636). The general dismissal of laboring women’s voices is fueled by the unjustified privilege regarding the epistemic authority of the physician. Thereby, violence appears as a natural element of childbirth, where violence has become an expected and accepted part of the birthing process, and is reproduced and reinforced by everyone involved: women, families, professionals, and decision-makers (Sadler et al. 2016:52). Women are not only dismissed and disbelieved by medical professionals, but they begin to doubt their own knowledge about themselves and their experiences.

The power that has been granted to medical professionals and taken from birthing women in the medicalized childbirth experience only serves to increase patient anxiety. Many women feel as though they do not have the right to express their doubts and concerns. They refrain from speaking up and going against the systemic norms out of fear of being humiliated, persecuted, or physically punished. It has been recognized that hospital staff will evaluate a pregnant patient in accordance with the problems she causes (Campero et al. 1998:396; Logan et al. 2022). Women who are more submissive, compliant, and quiet are treated better (Campero et al. 1998:398). At the cost of ignoring their patients and other methods of birth, health services often give priority to the biomedical process of childbirth (Campero et al. 1998:402). As a result, childbirth becomes a stressful event due to interactions between pain, immobilization, medical intervention, and lack of interpersonal relations and bodily autonomy within health care institutions (Campero et al. 1998:402).

The violence women are suffering at the hands of both male and female caregivers in the birthing scenario stems from structural gender inequality. As such, gender has become a central topic to the conceptualization of obstetric violence, allowing for the potential to address the structural dimensions of violence within the multiple forms of disrespect and abuse (Sadler et al. 2016:49). “The female body and its natural processes were - and continue to be - portrayed as abnormalities, disease, or deviances. Professionals lay discourses referring to the diagnosis of pregnancy, to pregnancy symptoms, and to the pregnant woman's return to the normal state after birth are some of several discrete markers of the male normalization” (Sadler et al. 2016:51). Obstetric violence reflects how female bodies in labor are objectified and seen as potentially opposing to femininity, or going against the controlled, submissive behaviors typically expected of women. The use of violence under this perspective becomes a necessary tool for the disciplining and restoration of the pregnant woman’s submission and passivity.

0 notes

Text

Epidurals can require laboring women to remain still for 10-15 minutes, even during contractions. Some anesthesiologists use fear of paralyzation to coerce women to comply with their demands.

0 notes

Text

Inadequate Communication

The current model of care is lacking in adequate and informative communication between patient and physician. Many of the case studies examined identified that there was practically no communication with any hospital staff, and that if there was, it was very quick, precise and delivered in an authoritarian manner (Campero et al. 1998:398). The lack of information provided by medical staff regarding the health of the woman and her child, hospital routines, and medical interventions contributes to feelings of abandonment and loneliness throughout the birthing process. Women's willingness to accept inadequate care and mistreatment out of fear has been taken for granted.

Communication issues within the birthing process have been recognized through several procedures. With epidural blocking, a procedure which includes the administering of numbing medication through injection in the back, it has been reported that comments made by the anesthesiologist during application were unclear and alarming, and that the doctors would use intimidation as a strategy to keep the women immobile (Campero et al. 1998:399). Episiotomies, too, being accepted as good for the mother and baby despite there being no evidence for this, are often performed without consent. When the women find out later that the procedure had been performed, they are made to feel as though they were at fault (Campero et al. 1998:399). Further, communication issues related to cesarean sections frequently leave women unsure as to whether they would undergo such a surgery as physicians procrastinate informing them until the time of delivery (Campero et al.1998:400). Kept in the dark about the status of their care, women are unable to process and accept what is happening and go through labor and delivery feeling frightened and guilty.

In highly medicalized birthing environments, women are rarely informed about the full range of options they are entitled to. Public, private, and professional discourse surrounding pregnancy and birth influence women’s expectations and perceptions of birth. They are encouraged to accept interventions through the instilled perceptions that birth is medical and negative in nature. This perception creates fear within the birthing scenario, leading to the perspective that while vaginal birth is preferred, cesarean surgery is the “easy” choice (Benyamini et al. 2017:425). “The World Health Organization (WHO) confirms that caesarean section rates higher than 10% are not associated with lower maternal and newborn mortality on a population level” (Sadler et al. 2016:49). The WHO has recognized that childbirth has become over medicalized, particularly in the case of low risk pregnancies; the cesarean rate worldwide is much higher than it needs to be (Lokugamage and Pathberiya 2017:2). Women enter the birthing scenario under the assumption that they will require some form of medical pain relief, which contributes to the overuse of obstetric technology and maintenance of health disparities.

0 notes

Text

Trained to Neglect

Many of the current practices within maternal care and services came with the industrialization of healthcare and the Evidence Based Medicine[1] movement (Lokugamage and Pathberiya 2017:3). These influences encouraged the practice of medicine through very scientific and objective methods, which greatly overlooks patient centered care. Though the doctors' decisions under this model were meant to be very rational, logical, and scientifically based, individual beliefs and preferences still persist. Complex health, social, political, and economic elements guided by risk, cost, and fear also influence professionals’ decisions at the expense of personalized care (Lokugamage and Pathberiya 2017:3). Some healthcare providers simply do not realize their insensitivity and loss of compassion: “We are trained not only in how to do such things but in how to do them almost without noticing, almost without caring, at least in the ways we might care in different circumstances or settings” (Lokugamage and Pathberiya 2017:3-4). From a tolerance of poor standards and a disengagement from managerial and leadership responsibilities within the healthcare system, dehumanized industrial healthcare persists. This failure to provide patient centered care was in part the “consequence of allowing focus on reaching national access targets, achieving financial balance and seeking foundation trust status to be at the cost of delivering acceptable standards of care” (Lokugamage and Pathberiya 2017:2). The existence of obstetric violence and lack of compassion for patients has also been justified with healthcare worker burnout (Lokugamage and Pathberiya 2017:4). Industrialized maternity services are lacking in compassion not only due to a lack of training, but from the discrimination and abuses linked to and reinforced by systematic conditions, such as multiple demands or disrespectful and degrading settings, and can be seen as a signal of a health system in crisis (Lokugamage and Pathberiya 2017:4). Obstetrics and gynecology as a speciality was noted as seemingly less supportive and having more undermining behaviors than any other specialties (Lokugamage and Pathberiya 2017:4).

[1] Evidence Based Medicine: medical practice or care that emphasizes the practical application of the findings of the best available current research

0 notes

Text

Discrimination in Care

The issue of obstetric violence intersects with multiple forms of stigma and marginalization based on one’s demographic and physical characteristics, as well as health statuses, which may severely affect the care experiences of pregnant and birthing women (Logan et al. 2022:758). Though experienced by all groups, women of low socioeconomic status, ethnic minorities, adolescent women, substance users, homeless women, women with lower education levels, and women without prenatal care experience significantly more adverse health outcomes and mistreatment during pregnancy and childbirth (Jardim and Modena 2018; Logan et al. 2022). From the Giving Voice to Mothers study, a national study that examines how race, ethnicity, and place of birth affect the maternity care, 17% of birthing people in the United States experience at least one form of mistreatment during maternity care, including verbal abuse, practitioner neglect, and privacy violations (Logan et al. 2022:750). Negative healthcare experiences throughout the pregnancy and birthing periods were more likely to occur if social and structural vulnerabilities were present (Logan et al. 2022:750). Such vulnerabilities include “being uninsured or publicly insured, poor, or experiencing violence, including structural racism and obstetric violence” (Logan et al. 2022:750). Women with higher-risk conditions reported the lowest levels of agency, along with a lack of person-centered, informed, consented interactions within the hospitals they birthed in (Logan et al. 2022:758).

Continued, nativity and multiparity also impacted the presence and degree of obstetric violence as those born outside the United States and those who had never given birth before were more likely to experience pressures of non-consented prenatal procedures (Logan et al. 2022:757). Though members from both Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) and white groups experience pressures and declined care at similar rates, it was identified that practitioners were more likely to accept the wishes of white patients while subjecting BIPOC individuals to non-consented procedures (Logan et al. 2022:758). It was also determined that those belonging to a minoritized race or ethnicity placed significantly more at risk of experiencing pressures if they had a physician or nurse as opposed to a midwife or birth practitioner present at the time of birth (Logan et al. 2022:754). BIPOC individuals are not only more prone to suffering from obstetric violence, but are two to three times more likely to die from childbirth, an issue believed to be a result of obstetric racism, among other potential causes (Cohen Shabot 2021; Logan et al. 2022).

0 notes

Text

Postpartum PTSD

The degrading treatment, loss of dignity, and serious damage women continue to suffer related to obstetric violence, along with the loss of control during birth can ultimately contribute to birth trauma, including postpartum post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (Diaz-Tello 2016:59). PTSD still remains largely unrecognized in maternity services and, unlike depression, is not routinely screened for. Affected women are therefore rarely identified and treated for PTSD (Ayers et al. 2018:2). The main risk factors for Postpartum PTSD include depression during pregnancy, fear of childbirth, negative birthing experiences, pregnancy or birthing complications, lack of support, and dissociation during birth (Ayers et al. 2018:2). Further, having a delivery plan that was not respected, use of fundal pressure, perineal tearing, postpartum hemorrhage, elective or emergency cesarean section delivery, newborn admission to the neonatal intermediate care unit, admission to the intensive care unit, infant formula feeding, verbal abuse, and psycho-affective[1] obstetric violence are also common risk factors for postpartum PTSD (Ayers et al. 2018; Martinez-Vazquez et al. 2021). In the City Birth Trauma Scale, an experimental questionnaire made to recognize symptoms of postpartum PTSD, it was reported that 90.6% of the women from one sample reported one or more symptoms of postpartum PTSD (Ayers et al. 2018:4). Currently, there are few validated measurements in use to identify postpartum PTSD.

[1] Psycho-affective: pertaining to the emotional aspects of an individual’s psychological composition

0 notes

Text

Legal Issues

Despite being invited to develop birthing plans, women worldwide continue to be excluded from participating in the design and evaluation of maternity care. This becomes evident as some countries have legislation which make it illegal or nearly impossible for healthcare providers to offer home birth services or midwifery-led birth centers (Sadler et al. 2016:48). In the many countries that do not practice informed maternity services, care is driven by local beliefs about childbirth and professional or organizational cultures (Sadler et al. 2016:48). Even in settings where out-of-hospital births are legal, planning and experiencing one can be extremely difficult and challenging for families and professionals. The biomedical model of care has a complex historical construction “with a consistent set of internal beliefs, rules and practices which responds to and reproduces gender ideologies across health professionals, the legal system and the state” (Sadler et al. 2016:50). Birthing women as a group are systematically disbelieved as a result of the implicit bias that women are less rational than men and lack certain epistemic capacities, which are historically grounded ideas about the uterus and the female reproductive system (Cohen Shabot 2021:642).

Though placed on feminist and public policy agendas, the issue of obstetric violence continues to be overlooked by medical and legal professionals and institutions. Through the “Organic Law on the Right of Women to a Life Free of Violence,” Venezuela became the first country to formally define the concept of obstetric violence as “the appropriation of women's body and reproductive processes by health personnel, which is expressed by a dehumanizing treatment, an abuse of medicalization and pathologization of natural processes, resulting in a loss of autonomy and ability to decide freely about their bodies and sexuality negatively impacting their quality of life” (Sadler et al. 2016:50). Since then, there has been resistance from health professionals from the concept of violence as it is contrary to their ethos. The framing of obstetric violence as a matter of violence and as a human rights violation allows us to acknowledge that practitioners and institutions are often unwittingly socialized to accept invisible forms of violence as normal happenings in reproductive care.

Birthing women become secondary elements in the birthing scenario under the law (Diaz-Tello 2016; Jardim and Modena 2018). The personal value that physicians and health attorneys ascribe to the fetus corresponds with their strong willingness to seek court-appointed procedures and interventions over the protest of an unwilling patient (Diaz-Tello 2016:60). Fetal interests become more compelling, which contribute to the violent policing of gender norms. Institutional rules separate women from social and cultural contexts, making them and others discredit their physiological capacity to give birth. Though guaranteed equal protection, women continue to experience gender discrimination throughout the birthing process. According to common tort law, anyone subjected to unconsented touching, regardless if for medical purposes, may sue for battery in most jurisdictions (Diaz-Tello 2016:59). There is no current law to protect this right for pregnant women. Those who do take legal action face issues with statutes of limitations or with healthcare providers, institutions, and courts reading in exceptions, preventing them from achieving legal progress.

Worldwide, women continue to be excluded from participating in the design and evaluation of maternity care as the current model fails to provide appropriate, evidence-based care. This becomes evident as some countries have legislation which make it illegal or nearly impossible for healthcare providers to offer home birth services or midwifery-led birth centers (Sadler et al. 2016:48). In settings where out-of-hospital births are legal, planning and experiencing one can be extremely difficult and challenging for families and professionals.

Legal case studies have revealed tragic occurrences and experiences of unconsented procedures and coercion. Studies of women who have pursued legal action after such violations and the outcomes of their cases demonstrate that the courts often favor the practitioners and healthcare systems over human rights (Logan et al. 2022:759). Forced cesarean surgery is a violent act that takes place in a setting where women are inferior to their doctors and other medical staff. In a society where women’s capacity for pregnancy has been historically used to sanction their exclusion from full citizenship; obstetric violence is more than a case of battery (Diaz-Tello 2016:59). Out of fear and insecurity about obstetric processes, birthing women become dependent and submissive, subjected to the wills of the professionals, holding them hostage to the violent cycle of obstetric violence (Jardim and Modena 2018:8).

Modern case law rejects the notion that pregnant women have any lesser entitlement to the fundamental right to bodily autonomy than any other person under the constitution (Diaz-Tello 2016:61). Still, women continue to experience limitations due to a lack of enforcement, lack of rights-based training among healthcare providers, and a failure to address infrastructural weaknesses (Diaz-Tello 2016:62). Practitioners significantly overestimate liability risks and irrationally prioritize fetal health, ascribing low value to any injury or failure of informed consent for pregnant women. This, along with the hesitation of legal authorities to criminally charge physicians, makes hospitals feel comfortable in making threats and intervening. There are rarely successful prosecutions for obstetric violence (Cohen Shabot 2021; Diaz-Tello 2016; Jardim and Modena 2018; Lokugamage and Pathberiya 2017; Sadler et al. 2016).

Of the few obstetric violence cases which have been taken to trial, each only lasted a matter of minutes (Diaz-Tello 2016). The juries sided with the hospitals, agreeing that the physicians had made the best possible choices for the mothers and their babies. To suggest that pregnant patients were to have the same rights as others, given the connotations the pregnant status invokes as that of hysteria, irrationality, and unreasonableness, would be naive and foolish. For the pregnant patients, there is a right to consent to the surgeries and procedures suggested by the medical professionals, but not a right to refuse them (Diaz-Tello 2016:59).

0 notes

Text

Activism

In 1993, Brazil launched one of the first discussions on obstetric violence with the foundation of the Network for the Humanization of Labour and Birth, where the region recognised the circumstances of violence and harassment in care settings (Sadler et al. 2016:50). Then, in 2000, Brazil held the First International Conference for the Humanization of Birth. At the conference, a group of Latin American activists, researchers, and health professionals gathered in response to the high rates of medical intervention in childbirth and growing recognition of abuses directed toward birthing women (Sadler et al. 2016:50). Since then, several Obstetric Violence Observatories have been founded, which, in 2016, released a common statement declaring obstetric violence as one of the “most invisible and naturalized forms of violence against women, constituting a serious violation of human rights” (Sadler et al. 2016:50).

Since then, the issue of obstetric violence has captured the attention of the WHO. In 2014, the WHO released a statement on the prevention and elimination of disrespect and abuse during facility-based childbirth (Lokugamage and Pathberiya 2017; Sadler et al. 2016). The disrespectful and abusive treatment women in childbirth facilities experience worldwide violates the rights of women. The statement released by the WHO and other organizations call for greater action, dialogue, research, and advocacy on this important human rights and public health issue. The WHO has urged governments and development partners to research, recognize, and redress abusive maternity care (Diaz-Tello 2016:58-61). Some existing organizations and movements include Human Rights in Childbirth (HRIC), the White Ribbon Alliance (WRA) Global Respectful Maternity Care Council, the Respectful Maternity Care (RMC) campaign, and the International MotherBaby Childbirth Organization (IMBCO) (Lokugamage and Pathberiya 2017:2). Collectively, their efforts present opportunities to highlight the institutional injustices and social inequalities which exist and call for broader reform.

Additionally, social media has become an integral part of the obstetric violence movement, and has become increasingly used by patients as a platform used to exchange views and lobby (Lokugamage and Pathberiya 2017:2). The incorporation of social media may have the capacity to shift the power relationship between patients and healthcare providers. On Facebook, pages such as “Spaces for Healing”, “The Positive Birth Movement”, and “They Said to Me” feature dozens of testimonies from women who were systematically and pervasively distrusted in childbirth. Hashtags such as “BreaktheSilence” and “realEBM” has also offered hundreds of women platforms to share their experiences of bullying, coercion, and unconsented procedures including episiotomies and vaginal examinations during birth (Diaz-Tello 2016:58-57-59). The women who have contributed to those platforms were relatable to each other in the sense that they left their birthing experience feeling betrayed and frightened in addition to the physical challenge of giving birth, and that many of them required therapy or changed the course of their reproductive lives (Diaz-Tello 2016; Lokugamage and Pathberiya 2017).

Though current activism is an extremely important step to the recognition of the issue of obstetric violence, it is not sufficient. Milli Hill, founder of the Positive Birth Movement, believes there is still a huge amount of polarity in the birth world, including that between women and the medical and legal system, midwives and obstetricians, holistic midwives and obstetric midwives, and doulas and doctors (Lokugamage and Pathberiya 2017:1). The current polarized environment does not create a suitable environment for women to give birth in. Trust has become lacking or is completely lost which has hindered the safety and freedom of birthing individuals.

0 notes