Text

Post Election 2016

Post Election 2016 – What Do We Do Now?

A sermon by Meredith Guest

Delivered at the Unitarian Universalist Congregation of Petaluma on December 11, 2016

Luke 6:27-36

If the recent election of Donald Trump was anything, it was a slap in the face to every progressive, liberal minded American. And make no mistake, it was an intentional slap in the face; that was a great part of the man’s appeal to those who voted for him. And so we, like the cast of “Hamilton,” the diverse Americas who are alarmed and anxious that [this] new administration will not protect the hard-won rights of the last 50 years have been intentionally slapped upside the head with a 2x4 branded with the name of Trump. With our ears still ringing, our eyes still smarting, our values run down like so much road kill, what do we do now?

In the passage from Luke I just read, Jesus says, if someone slaps you upside the head, you are to willingly offer up the other side for equal treatment. But like so much of the Bible – most of it, actually – this isn’t to be taken literally. What he means is: you are to be the one where the violence stops; that’s why you turn the other cheek. What I have to decide now is: Will I be the person who chooses to let the violence stop with me? And what you have to decide is: Will you be the one who willingly and freely chooses to have the violence stop with you.

It goes without saying, this is not our default setting. When slapped upside the head, we are programmed to fight or flight, and unless you plan to leave the country, there’s really nowhere to run; this guy is president. But I must remind you that fight or flight is also the default setting of a gerbil, and if being human means anything, surely it means we are not limited to the default setting of gerbils. It’s one thing to hold to the principles of Unitarian Universalism when YOUR guy holds the reins of power, but what about when evil is at the gate? What do we do then?

1. For one, start looking for ways to make peace.

Mark Lilla in the NYT writes: “But the fixation on diversity in our schools and in the press has produced a generation of liberals and progressives narcissistically unaware of conditions outside their self-defined groups, and indifferent to the task of reaching out to Americans in every walk of life.” (Mark Lilla, NYT, 11/18/16) The only remaining slur acceptable in polite company is “redneck;” and if children are not present, it is often accompanied by an expletive.

The poet Adrienne Rich has said, “When someone with the authority of a teacher describes the world and you are not in it, there is a moment of psychic disequilibrium, as if you looked into a mirror and saw nothing.” This quote used to apply to me and to others in the LGBT community. But not anymore. Now our faces are everywhere you look, while the faces of working class Americans, those faces that used to be THE face of America, are disappearing, rendering them anonymous and their lives invisible.

I once had a child in my class with severe cerebral palsy. She was my student in 4th, 5th and 6th grades. Her name was Johanna and she was a wonderful student. One summer just before the beginning of school, Johanna’s mother recommended I meet with an occupational therapist that they had been seeing. I agreed, and in our meeting he asked me to describe the classroom and Johanna’s place in it. After I did so, he looked at me and said, “This child’s not a member of your classroom. She’s little more than a fixture. No meaningful interaction happens between her and the other members of the class…” This was a “take no prisoners” kind of guy, but I took his words to heart and came up with a plan. I cleared it with the mother and soon after school began, the class did a group challenge. Privately I gave Johanna information that the class had to get from her without the assistance of her aid or any other adult. Only when they got this information would they be allowed to go to recess. It wasn’t easy, but they got the information, went to recess and after we did a few similar things, pretty soon I saw students interacting with her in ways they never had before.

It seems to me we, as a nation, have a similar group challenge. While the well educated, well connected and well endowed have enjoyed the fruits of the modern economy, Donald Trump has sounded a take-no-prisoners wake-up call for those with ears to hear and eyes to see that a whole group of others have been left behind. While technically part of the country, they are like the handicapped kid in the wheelchair who nobody ever talks to and everybody tries to ignore. But in this case, a lot more than recess is at stake.

One of my sources for this talk is the book Deer Hunting With Jesus by Joe Bageant. I’ve also drawn from interviews with J.D. Vance as well as his book Hillbilly Elegy. I have read both, and I highly recommend Deer Hunting with Jesus. Bageant grew up in a small town in Virginia. After high school he went off to college, became a successful journalist and lived for many years in New York City. When talking to his many liberal friends, he would often be asked why rural southerners so often voted in ways that were contrary to their self interests. Finally, toward the end of his career, he moved back to his hometown and set about trying to answer that question. Deer Hunting With Jesus is the result.

When Bageant interviews his old classmates, one of the things he discovers is that none of them knows a liberal. Their own thoughts, their own views and opinions are constantly being reflected back to them and little or nothing to the contrary has a chance to get through. Their lives and the milieu in which they live are insular.

But that’s not just true of conservatives.

During the election I saw a FB post in which a person demanded, “Anyone voting for Trump, please unfriend me.” Pretty soon, we’ll all be living inside intellectual and ideological gated communities where the only people we talk to and hear from are those who think like us.

One of the best things about being a financial failure as an author is that economic necessity forced me out into the world. Had I been successful, I would have sequestered my big old queer self in my cozy little study and spent my days happily writing lies. As it is, I have to work, and so, at least 3 days a week, I substitute teach in schools all over Petaluma from grades 3-12. As a result, hundreds of children get to rub shoulders with a real, live, breathing transsexual who, unlike the ones they see in the media, is not rich, famous or sexy. And whenever I can, I make it a point to interact with the kids in their Mossy Oak camo sweatshirts, because I am likely to be the only transsexual person they ever get a chance to be around, and I want them to know I think they matter, and that I care about them. They don’t always warm up to me. They certainly don’t all like me. They can be cruel. But this is what I can do. I can reach across the divide and offer myself in friendship.

And so can you, but to do that we’ll all have to:

- Stop having a litmus test for who is and who is not worthy of conversation. We need to be talking with racists. In the Nov. 26 issue of the NYT, there is an op/ed piece entitled “Why I Left White Nationalism” by Derek Black. Mr. Black grew up in a white nationalist family — David Duke was his godfather, and his father started Stormfront, the first major white nationalist website — and he was once considered the bright future of the movement. What changed him is – and I will let him speak for himself – “ I began attending a liberal college where my presence prompted huge controversy. Through many talks with devoted and diverse people there — people who chose to invite me into their dorms and conversations rather than ostracize me — I began to realize the damage I had done. Ever since, I have been trying to make up for it.

- We need to stop policing speech like English teachers police grammar. It just shuts people down.

- We are going to have to engage in forbidden conversations, e.g. immigration, abortion, gun rights, religion. And when we engage in these conversations, we must do unto others as we would have them do unto us; which is to say: listen, be curious, be open to their side of the issue, and be prepared to alter or change our own views, and look for any and all common ground. There IS common ground there, but we’ll never find it if we don’t talk to one another.

2. We need to be more critical of our own thinking and aware of our biases.

Under the best of circumstances, even for well educated people, it is hard to be aware of and critical of our own presuppositions and the presuppositions of our group.

I remember on day saying to a little boy in my class, When you meet the right girl… and later, I thought to myself, how do you know he’s not gay? It’s so hard to see those heteronormative presuppositions, but once I did, whenever I had cause to say something similar, I would say, When you meet that special person…It was easy to fix, once I recognized the unconscious presupposition.

Being an educator, I’m especially aware of the presuppositions and prejudices that guide so much of our thinking about school.

The poet, thinker and social prophet, Wendell Berry has said, “A powerful superstition of modern life is that people and conditions are improved inevitably by education.” (W. Berry, What Are People For, pg. 24) (I know a high school principle who puts a quote by Oscar Wilde at the end of her emails: You can never be overdressed or overeducated.) He then goes on to tell the story of Nate Shaw, the pseudonym for a black farmer born in Alabama in 1885. When he finishes paying a moving and eloquent tribute to this remarkable man, he asks: So do you think Nate Shaw would have inevitably been improved by education? Clearly the answer is no. And there are all sorts of successful people, some of whom have made tremendous contributions, who have not been well educated. Would they have inevitably been improved by education? That’s not a given. In fact, as Berry points out, if life on the planet is destroyed, it will almost certainly be by the college educated.

One unfortunate, even dangerous, consequence of this superstition about education is it has led to the denigration of physical labor and the people who do it.

When I went from being a school bus driver to being a substitute teacher, I realized just how differently people see those two occupations and the people who do them. Never mind that, as a bus driver, I made more money and had more authority over the children in my charge, my movement from a blue collar worker to a white collar worker was initially viewed with considerable suspicion by many “white collar” teachers.

I recently saw one of those inspirational posters hanging on the wall of a middle school classroom. It began: “I can be…” then went on to list a slew of possible occupations that were colorfully inscribed on a black background in the shape of a light bulb, symbolizing, I assume, that these were occupations of the enlightened or occupations that would bring enlightenment – or, probably, both. Here’s a quick rundown of some of the occupations listed: software developer, doctor, meteorologist, airplane pilot, anthropologist, microbiologist, epidemiologist, astronaut, cartographer, network analyst, medical scientist, computer programmer, veterinarian, zoologist, geographer, archeologist, architect, conservation scientist and so on down to chemist. I found it ironic that nowhere on this classroom inspirational poster did I find the occupation of – teacher.

Our life on this planet depends on 6 inches of topsoil and the occupation most directly involved with the stewardship of this vital resource, farming, is not, and will likely never be, on the list of things we want our students to aspire to. But the truth is, we could lose every occupation on that poster, and we’d still survive, but without 6 inches of topsoil and the knowledge of how to farm it, we’re just so many skeletons littering the face of the planet.

We need to recognize that no matter how enlightened we imagine ourselves to be, we are not immune to unexamined presuppositions, biases, prejudices and even superstitions just like those damn conservatives.

3. “We must be able to imagine ourselves as peacemakers,” the great poet and prophet Wendell Berry writes. “The serious question is whether you're going to become a warrior community and…I think the only antidote to that is imagination. You have to develop your imagination to the point that permits sympathy to happen. You have to be able to imagine lives that are not yours or the lives of your loved ones or the lives of your neighbors. You have to have at least enough imagination to understand that if you want the benefits of compassion, you must be compassionate. If you want forgiveness you must be forgiving.

It's a difficult business, being human.” (Wendell Berry, Sojourners magazine July 2004)

Contrary to what the pundits say; contrary to the vote talley, there are not 2 Americas; there is only one America, and we are all its citizens. We need to eschew the narrative of us vs them. It is only us; it’s only we.

There’s a beautiful story of what that looks like, but – trigger warning – I’m going to have to read from the Bible again.

Luke 19:41 - Jesus weeps over Jerusalem.

So Jesus climbs to a high place where he can look down on the city of Jerusalem, who’s name in the ancient tongue is “city of peace.” Say what you will about the man, but he was not an idiot. He knew the fate that awaited him there; knew that, short of a miracle, the residents of that city, many who had flocked to hear him in the early days, would turn on him like a pack of hyenas; knew that the leaders would finally succeed in what they had been trying to do for years: kill him. He looks down on the city where he knows he will be murdered; and he weeps for it. Now maybe he wept for himself as well; for his followers who he loved and who he knew would be so heartbroken and bereft without him; maybe he wept for the failure of his vision, his hope, his dream for a different kind of Kingdom. Surely, if only in our imaginations, we can allow him that. But Luke shows him weeping for the city itself: “My people, my people…”

If we are going to rise above the default setting of gerbils and be the people where the violence stops, this, it seems to me, must become our prayer: “My people, my people…” Not just “our people,” not “those people,” certainly not “you people” – My people. It is in this prayer, it is in this position, this stance, that we become the peace for which we pray. “My people, my people…”

But that’s not the end of the story, because the next thing that happens, the very next thing…well, let me read it:

Luke 19:45 - Jesus cleanses the temple.

This passage requires a bit of exegesis to understand fully. Contrary to what the text would seem to indicate, it is likely that Jesus was not upset with the money changers themselves. The exchange of coinage was essential to the operation of the Temple. When Jesus overturns the tables of the money changers, he is, in effect, shutting down the normal operation of the Temple. Why? Because beginning with Herod and continuing after his death in 6 BCE, the temple was, in addition to its legitimate cultic function, the center of local collaboration with Rome. The temple, which was to be the house of worship of the God of liberation, of justice and mercy had come to be run by officials, installed by Rome, who colluded with the Empire for their own profit. The Empire, in turn, followed the economic rules of the domination system, which, briefly, was rule of the many by the few, economic exploitation, with religious legitimation. In other words, the Temple then like the church now, especially, as we saw in the election, the evangelical church, has become the handmaiden of the Empire, pronouncing divine sanction on the status quo. This is the temple Jesus shuts down. And he’s not exactly peaceful about it either.

You know those airline miles you’ve been accumulating? You might want to save them. I just gave a bunch ours to Lia so she can attend the Million Woman March in DC on Jan. 21. “I need to do it for my daughter,” she said. You know your bucket list, you might need to dump it out and replace it with direct acts of resistance. You know that vacation you were planning? You might need to be prepared to sacrifice it for something bigger.

And then, you know what happens next according to Luke? Jesus is found teaching.

Look, I know you’re not biblical people, but you’ve got to admit, this is not a bad program: grief, direct action, teaching. But I cannot emphasize enough: it all depends on our willingness and our ability to pray the prayer: “My people, my people…” And I hope you will hold that prayer in your hearts and your minds as we sing our closing hymn: “We’ll Build A Land.”

AMEN

0 notes

Text

Pre-election 2016

A sermon by Meredith Guest

Delivered to the Unitarian Universalist Congregation of Marin 10/9/16

Luke 6:27-36

For many years I had the great pleasure of being a teacher of 4th, 5th, and 6th graders in a little Montessori school. After the students were gone, while engaged in the Sisyphean task of checking papers, I would occasionally find a student’s answer to a math problem that was not just wrong, but made absolutely no sense. It’s as if I’d asked for the square of 6 and they’d given me the time of day. Now I will confess to you that sometimes my response to these students was not especially charitable. “Sweet Jesus,” I was known to exclaim, “I’d have an easier time teaching math to the class guinea pig!” But, save for with my colleagues, I kept these thoughts to myself. The next day, I’d call the student over to my desk and, in my most neutral voice, ask, “Uh, can you tell me how you got this answer?” And after studying the problem for a moment, the student would invariably explain how they got this completely wrong answer in a way so logical as to be downright brilliant – wrong, but brilliant.

Most of my friends are like you; they’re well educated, progressive, liberal thinking people. And most of them are apoplectic at the possibility that Donald Trump might be elected president. “What is wrong with these people?” they wail. “Are they just stupid?!” “Don’t they realize they’re choosing against their own self interests?!” And, for the most part, they do not keep these thoughts to themselves. Personally, I find it ironic that these mostly atheists are having a downright Old Testament experience: weeping, wailing and gnashing of teeth. What we haven’t done, it seems to me, is stop, take the time and exert the energy to actually listen to Trump’s supporters, and if we did, I think we would find – as with my students – there is a kind of logic here.

This logic based on several things, and key to it is:

Insularity.

One of my sources for this talk is the book Deer Hunting With Jesus by Joe Bageant. I’ve also drawn from interviews with J.D. Vance about his book Hillbilly Elegy. I have not read Hillbilly Elegy but I highly recommend Deer Hunting with Jesus. Bageant grew up in a small town in Virginia. After high school he went off to college, became a successful journalist and lived from many years in New York City. When talking to his many liberal friends, he would often be asked why rural southerners so often voted in ways that were contrary to their self interests. Finally, toward the end of his career, he moved back to to his hometown to see if he could answer that question. Deer Hunting with Jesus is the result.

When Bageant interviews his old classmates, one of the things he discovers is that none of them knows a liberal. Their own thoughts, their own views and opinions are constantly being reflected back to them and little or nothing to the contrary has a chance to get through. Their lives and the milieu in which they live are insular.

But then, that’s not just true of conservatives.

In the 9/19/16 issue of the New Yorker, the author observes: “Fewer than 1 in 4 Americans ever talk with someone with whom they disagree politically; fewer than 1 in 5 have ever met with people holding views different from their own to solve a common problem.” To which he asks, “What kind of democracy is that?”

And social media, with a cheap, easy and convenient capability of bringing together diverse people and opinions, has only made the problem worse. I recently saw a FB post in which a person demanded, “Anyone voting for Trump, please unfriend me.” Pretty soon, we’ll all be living inside intellectual and ideological gated communities where the only people we talk to and hear from are those who think like us.

When I came out some 16 years ago, I expected it to be harder for Caleb, my son, since high school boys are arguably more homophobic than girls, but Lia, his younger sister, had her own times of difficult misgivings. It was hard for her, too, and years later, Lia reported that the most annoying thing she had to deal with was, once she revealed that her dad was transsexual, not only did she have to explain what that meant, but that then, she had to assure them that I did not dress like a hooker.

I tell that story to illustrate the power of the personal. In the abstract, to hear that Lia and Caleb’s dad dressed and lived her life as a woman was strange, to say the least. But once they got to know me, I wasn’t particularly strange. It’s by knowing one another we come to understand one another and while we may not agree, personal relationship is far better soil for the flowering of compassion than the concrete foundation of a gated community.

One of the best things about being a financial failure as an author is that it forced me out into the world. Had I been successful, I would have sequestered myself in my cozy little study and spent my days happily writing lies. Even in retirement I have to work, and so, at least 3 days a week, I substitute teach in schools all over Petaluma from grades 3-12. As a result, hundreds of children get to see a real, live, breathing transsexual who, unlike the ones they see in the media, is not rich, famous or sexy. And I make it a point whenever I can, to interact with the kids in their Mossy Oak camo sweatshirts; not because I want to change their minds about anything. I just want to get to know them; I think they matter; I care about them. They don’t always like me or warm up to me. They can be cruel, though usually not overtly. But this is what I can do. In many ways, it’s all I can do. Perhaps it is enough.

Insularity leads to:

Uncritical thinking.

Under the best of circumstances, even for well educated people, it is hard to be aware of and critical of our own presuppositions and the presuppositions of our group.

I remember on day saying to a little boy in my class, When you meet the right girl… Later, I thought to myself, how do you know he’s not gay? It’s so hard to see those heteronormative presuppositions. Once I did, whenever I had cause to say something similar, I would say, When you meet that special person… It was easy to fix, once I recognized the presupposition.

And what about the presupposition that all male babies grow up to be boys and men while females grow up to be girls and women. Clearly, that’s not true. I have a 7 month old grandchild, and what we know about my grandchild is that she’s female. It’s too early to tell whether she’s also a girl or not; but I hope so. Having a brain and a body at odds with one another is not something I would wish on anyone. I’m not suggesting we have to relinquish our presuppositions; I still speak of my granddaughter and refer to her with feminine pronouns. I just think it’s very important to be aware of them. Operating at the level of our unconscious, presuppositions can be damaging, even dangerous.

Being an educator, I’m especially aware of the presuppositions that guide so much of our thinking about school.

I once did a subbing gig in which I was the co-teacher in a high school English class. The teacher, a lovely, very caring person, was exhorting her students to bring the rough drafts of their essays to her at the tutorial period to have her critique them. “Why do you think you might want me to critique your writing?” she asked. After a moment, a boy ventured, “So we can get a better grade.” “That’s right,” she agreed, and it was everything I could do not to cry out, “No, it’s so you’ll become a better writer.” School is about education; it’s not about grades; it’s not about college; it’s not about what job you’re going to have and how much money you’re going to make once you get out. It’s about becoming educated. It’s about learning how to think, to reason, to question, to grow, to become a lifelong learner.

The poet, thinker and social prophet, Wendell Berry has said, “A powerful superstition of modern life is that people and conditions are improved inevitably by education.” (W. Berry, What Are People For, pg. 24) But that’s clearly not true. There are all sorts of successful people, some of whom have made tremendous contributions, who have not been well educated. Would they have inevitably been improved by education? I don’t think that’s a given.

One unfortunate, even dangerous, consequence of this superstition about education has led to the denigration of physical labor.

I recently saw one of those inspirational posters hanging on the wall of a middle school classroom. It began: “I can be…” then went on to list a slew of possible occupations that were colorfully inscribed on a black background in the shape of a light bulb, symbolizing, I assume, that these were occupations of the enlightened or occupations that would bring enlightenment – or both. Here’s a quick rundown of the occupations listed: software developer, doctor, meteorologist, airplane pilot, anthropologist, microbiologist, epidemiologist, astronaut, cartographer, network analyst, medical scientist, computer programmer, veterinarian, zoologist, geographer, archeologist, architect, conservation scientist and so on down to chemist. I found it ironic that nowhere on this classroom inspirational poster did I find the occupation of – teacher.

It makes me wonder if these educators ascribe to a philosophy I found in a Terry Pratchett novel. In the story, Death has decided he wants a new occupation; he’s just done with dealing with the dying and the dead, so he goes to a career counselor. After an extensive interview, the counselor says, “It would seem you have no useful skill or talent whatsoever. Have you ever thought of going into teaching?” Maybe they should hang that next to the “I can be…” poster.

Our life on this planet depends on 6 inches of topsoil and the occupation most directly involved with the stewardship of this vital resource, farming, is not, and will likely never be, on the list of things our students might aspire to. But the truth is, we could lose every occupation on that poster, and we’d still survive, but without 6 inches of topsoil, we’re just so many skeletons littering the face of the planet.

This kind of lazy liberalism that considers itself so enlightened as to have no unexamined presuppositions and certainly no superstitions is one of the things I like least about living in the Bay Area. And just like the unexamined presuppositions and superstitions held sacred by conservatives, ours are enabled, in part, by insularity and uncritical thinking.

Anger and a desire for revenge.

In Hillbilly Elegy Vance describes the Appalachian town in which he grew up. In the 70s and the 80s the industrial jobs began to disappear, jobs that made a middle class lifestyle possible to people with a high school education. Now the town is full of shuttered storefronts. More people die of suicide from drug overdoses than from natural causes, families are disintegrating, and single mothers raise the majority of children. Church attendance is at historic lows, high school graduation rates are dropping, and few students go on to college. There’s something “almost spiritual,” Vance says, “about the cynicism” in his hometown.

Who speaks for these people; who represents them; who cares about them? I’ve heard liberals say things about Trump supporters, they would never dream of saying about Muslims, or immigrants, or African Americans, even though many within those groups also hold views liberals find abhorrent. Since when did it become okay to demean poor, uneducated white people? Since when did they become fair game for our ridicule? And make no mistake, I am not innocent here.

You will likely recall when the North Carolina legislature passed the bill banning transgender people from using the bathroom that corresponds to their gender identity. When President Obama came out very publically against this bill and in support of transgender rights, he was applauded by rights’ groups, but I was suspicious. For one thing, it seemed out of character for this president who has been slow, almost timid, in taking sides on controversial issues. Also, North Carolina was already under tremendous economic pressure to repeal the legislation. It seemed to me the President’s public support merely hardened the resolve of the Right. Furthermore, what I was reading and seeing in the news about that time was that rural, white voters were beginning to sit up and take notice of the things Bernie Sanders was saying. Here was a Democrat and a liberal who was addressing the issues that mattered to small town people who had not that long ago been stalwart democrats. But when Obama, who they despise, threatened to cram transgender rights down their throats just like gay marriage had been crammed down their throats, this very effectively drove them back into the folds of the Republican party. This, I believe, was the intentional strategy of the Democratic establishment who, fearing a Sanders victory, decided Hillary wouldn’t need these voters to win, and so, rather than try to bring them back into the fold of the party, they wrote them off – again.

The poet Adrienne Rich has said, “When someone with the authority of a teacher describes the world and you are not in it, there is a moment of psychic disequilibrium, as if you looked into a mirror and saw nothing.” This quote used to apply to me and to others in the LGBT community. But not anymore. Now our faces are everywhere you look, while the faces of working class Americans are disappearing, rendering them anonymous and their lives invisible.

Nobody cares about them, about the rural communities they call home, about their traditions or their way of life. And nobody represents them, and they are angry and looking for revenge. That’s why whatever Trump says or does, however absurd, outlandish and mean, that sticks a finger in the eye of the elites who run the country, be they Democrat or Republican, the more they love him. In fact, you might say, through Trump the people who we don’t know, don’t like, and don’t agree with have slapped us in the face; and we have done everything but turn the other cheek. What do you suppose would happen if, rather than insult, malign, and demean, we did; we turned the other cheek?

I once had a child in my class with severe cerebral palsy. She was my student in 4th, 5th and 6th grades. Her name was Johanna and she was a wonderful student. One summer just before the beginning of school, Johanna’s mother recommended I meet with an occupational therapist who they had been seeing. I agreed, and in our meeting he asked me to describe the classroom and Johanna’s place in it. After I did, he looked at me and said, “This child’s not a member of your classroom. She’s little more than a fixture. No meaningful interaction happens between her and the other members of the class…” This was a “take no prisoners” kind of guy, but I listened to him and came up with a plan. I cleared it with the mother and soon after school began, the class did a group challenge. Privately I gave Johanna information that the class had to get from her without the assistance of her aid or any other adult. Only when they got this information would they be allowed to go to recess. It wasn’t easy, but they got the information, went to recess and after we did a few similar things, pretty soon I saw students interacting with her in ways they never had before.

It seems to me we, as a nation, have a similar group challenge. While the well educated, well connected and well endowed have enjoyed the fruits of the modern economy, Donald Trump has sounded a take-no-prisoners wake-up call for those with ears to hear and eyes to see that a whole group of others have been left behind. While technically part of the country, they are like the handicapped kid in the wheelchair who nobody ever talks to and everybody tries to ignore. But in this case, a lot more than recess is at stake.

So I want you to imagine, instead of a sweet, bright child with cerebral palsy in that wheelchair, picture a laid-off West Virginia coal miner who dropped out of high school, lives in a dilapidated trailer with his girlfriend, her 2 snotty nosed kids and a pit bull. He owns an AR15 assault rifle, drinks Bud light, and hates Obama.

And then, I want you to remember your first 2 principles: 1) The Inherent worth and dignity of every person; 2) Justice, equity and compassion in human relations – all human relations, both private and corporate.

And I want you to hold that picture next to those principles when we sing our closing hymn, “We’ll Build A Land.”

We’ll Build a Land

We’ll build a land where we bind up the broken.

We’ll build a land where the captives go free

Where the oil of gladness dissolves all mourning

Oh, we’ll build a promised land that can be.

Chorus: Come build a land where sisters and brothers

Anointed by God may then create peace

Where justice shall roll down like waters

And peace like an ever flowing stream.

We’ll build a land where we bring the good tidings to

All the afflicted and all those who mourn.

And we’ll give them garlands instead of ashes,

Oh we’ll build a land where peace is born.

Chorus

We’ll be a land building up ancient cities

Raising up devastations from old;

Restoring ruins of generations,

Oh, we’ll build a land of people so bold.

Chorus

Come build a land where the mantles of praises

Resound from spirits once faint and once weak;

Where the oaks of righteousness stand her people,

Oh, come build the land, my people, we seek.

Chorus

1 note

·

View note

Text

The P.C.T.

On a recent trip to the mountains I took a wonderful short hike that crossed the Pacific Crest Trail. Seeing the emblem marking the PCT nailed to a large pine, I instantly felt sharp pains of grief. Thirty five years ago I had been planning to leave Marsha and hike the PCT alone in a desperate attempt to sort out my life, my marriage, my future, and, most of all, my gender. When she announced she was pregnant, those plans came to a sudden and ignominious end as dramatic and depressing as a car crash. Gazing at that emblem, my heart ached, my eyes filled with tears. Here was a road I did not take, a life I did not live, a future I would never know. What might my life have been like had I walked this path? Where would I have gone? What might I have done? The marriage undoubtedly would have ended, as it should have, as it did, there would have been no children, and I would have been out west, in the mountains for which my heart so often longed. For 10 minutes or so I was in the grip of this grief, then I realized: I am not unhappy. No, this is not the way I imagined my life would turn out, but, given the circumstances, I am extremely lucky, blessed even. Nor would it have mattered which of the imaginable possibilities I chose then, being transgender was as much a part of me as my DNA; it could not forever be denied.

But isn’t that what we do in old age – look at the doors we didn’t open and wonder and wish and imagine and grieve? Perhaps I should take comfort in knowing that given the time and place of my birth, being trans would have made any successful outcome to the available choices impossible. And I do find some comfort in that, in knowing that whatever road I might have taken, it would have bent to some version of the circumstances in which I now find myself – maybe worse, maybe better.

At least now I’ve walked through the forbidden door I tried so hard not to and the worst I imagined did not happen. Quite the contrary. I have found more love than I could have hoped for, certainly more love than I ever deserved, and an amazing measure of peace in who and what I am. Now the time before me is much less than what has passed, and while I do not long for death neither do I dread it. Plus, barring a miracle or a catastrophe, there’s a measure of freedom in knowing that there are few doors left to be opened, that the way before me is clear, the end certain and sure and, so far as I know, final. And, to answer the poet Mary Oliver, I did not waste this one wild and precious life I was given. Maybe I didn’t live it the way I wanted; maybe it didn’t turn out the way I hoped; maybe I could have chosen better, but at least I didn’t waste it.

And so, I continued on my hike and lo and behold: wonderful things awaited me, fascinating and lovely things to be seen, explored, discovered and learned.

0 notes

Text

To Hide or to Fly

I’m subbing at a large high school where the closest staff bathroom is at the gym. As I turn the corner of the building, I see a circle of boys, some wearing their letterman’s jackets, turn and stare. They’re too far away to hear what’s being said, so maybe they’re just admiring my new cowboy boots, at how nicely they go with my long denim skirt – but not likely. Probably it’s more along the lines of: There’s that sub who used to be a man – or worse.

At lunch I’m outside walking to the office when I hear my name called, my first name. I turn and there’s another group of boys, though this time they’re pretending not to notice. Harassing me openly would get them into trouble, so they’ve developed a variety of creative ways to do it surreptitiously.

Sometimes – increasingly – moments like this just annoy me; sometimes they amuse me; sometimes they make me want to do something outrageous – You think I’m interesting? Well take a look at this! But when I’m vulnerable, when they come too hard and too fast, when they’re particularly well aimed, moments like this make me feel ridiculous, stupid and ugly. I want to crawl under a log like some sort of bug and hide. The lid on my gender Dysphoria lifts and out crawls something from an “Alien” movie that begins to attach itself to me. A litany of mean and cruel things I’ve heard said about queer people starts playing through my head like the Top Ten Hits on the radio. All I can do then is just keep moving and hope the depression to follow won’t be too deep or too long.

On a break I’m walking down a hallway when I see a boy I know approaching. He’s probably a junior now. He’s got on his jeans, work books, his camo jacket and cap. As we get close, he spontaneously holds open his arms, and in the middle of the high school hallway, we hug. “Mer,” he says simply. “Russell,” I respond. “It’s good to see you.” Then, without further ado, we continue on our respective ways. Moments like this make me feel like I could spread my arms like wings and fly.

Now I have a choice. And it’s completely and totally my choice. Of course, like every choice, it’s not made in a vacuum. In so many ways I am blessed. I have a solid network of support around me. I have people who love me, who’ll stand up for me, who’ll support me, and a precious few who’ll call me on my shit. I have work that most days I like. I have plenty of food to eat and a lovely place to live. By the same token I’ve known loss. I lost the work I loved and at which I excelled. I’ve failed. I’ve spent more years hating myself than loving myself, and that does damage that can never fully be fixed. All of this – the good, the bad and the ugly – comes into play when I choose.

The choice I must make is: Which of these experiences will I give energy to? On which will I focus my attention? What prominence will I give each in the narrative of my life I tell myself and others?

Make no mistake, this is no small choice. Which I choose will determine if I can survive in this work; which I choose might well determine if I survive at all.

So what will it be: to hide or to fly?

If I say it is to fly, to choose the hug and not the taunt, that is not the same as choosing to “accentuate the positive, eliminate the negative” as the old song and simplistic philosophy goes. This choice and the ramifications of it are too big for that puny little boat.

For one thing, I don’t wish to eliminate the negative. The suspicion, the phobia, perhaps even the hate will find some outlet, some target. Why not me? I’m not a vulnerable teenager. While not immune to the arrows of insult, my hide has grown pretty tough and the disfavor of studly high school boys is of little consequence to me. As a teacher, even a substitute teacher, I have the protection and privilege of authority, so why not absorb as much of it as I can?

So even though my brain is wired like everyone else’s to pay closest attention to what is potentially threatening, I choose Russell’s hug. I choose the hug because it is the most worthy to be chosen. In the living of the closing of my days, it is the experience I return to, that I roll around on the tongue of my mind like a cherry lifesaver, enjoying again and again its sweetness. The other, the stares and taunts, fade into colorless shadow remembered like an old wound, a pale scar.

This is the choice, perhaps the only real choice I have, given the circumstances. I could choose differently; I have chosen differently. But not this time. This time I choose to fly and not to hide. The view is so much better.

�

0 notes

Text

The Wages of Sin - A Reflection on Gun Violence

The Apostle Paul in his letter to the Romans says, “The wages of sin is death.1” Many of us view this kind of religious language as hokey, embarrassing, and ridiculously old-fashioned. The writings of Paul are rife with it.2 One problem, of course, is what is meant by sin.

At some point in the development of Christianity, aided by the words of the aforementioned apostle, sin came to be defined primarily as personal acts of impropriety. While I think an argument can be made and has been made by none other than the esteemed Wendell Berry as to the value and importance of propriety, I think it’s fair to say that the organized church has so trivialized sin as to make it as toothless as a newborn. For instance, growing up in Mississip in the Southern Baptist Church, I knew dancing and drinking and petting (which I eventually figured out had something to do with sex and second base) were sins. Homosexuality and certainly transsexuality were not only sins but sins of the highest order, so that I was without doubt going to burn in hell for all eternity – which is a hell of a long time when you stop to think about it. But I never once heard that racism was a sin. Not once. Heinous acts of discrimination, cruelty and bigotry were being practiced around me on a daily basis. An entire group of people was being stigmatized, impoverished and denied basic human rights, but that was never identified, never even hinted at as sinful. In fact, it wasn’t until 1995 that the Southern Baptist Convention apologized for its support of slavery and segregation. That’s just a little over 20 years ago.

By contrast, some thirty years ago I heard Gordon Cosby3 define sin so differently I never forgot it. In not one but many sermons, he forcefully indicted, not me as an individual, but the United States as a nation and I a citizen of it for being the arms dealer of the world. It was with interest, then, that, with more than a touch of irony, on Christmas day of last year, the “New York Times”4 ran an article proclaiming “U.S. Foreign Arms Deals Increased Nearly $10 Billion in 2014.”

Here are a couple of quotes from the article:

“American weapons receipts rose to $36.2 billion in 2014 from $26.7 billion the year before, bolstered by multibillion-dollar agreements with Qatar, Saudi Arabia and South Korea. Those deals and others ensured that the United States remained the single largest provider of arms around the world last year, controlling just over 50 percent of the market.” (Can you think of a place in the world less in need of more weapons than the Middle East?)

“Despite the competition, the report concluded that, given its positioning, the United States was likely to remain the dominant supplier of arms to developing nations in coming years.” (Do you detect the barely concealed swelling of the chest?)

With that in mind, take a fresh look at the crusty old Apostle’s claim, “The wages of sin is death.” Not hokey now nor out of date, huh? Rather, painfully prophetic.

Finally, and justifiably it might be argued, the American weapons which have been used to wreck havoc and destruction and death all over the world have come full circle. The dots are being connected. The weapons we have sent around the world to kill and maim and murder have come back home to roost. Now they’re available in your local Wal-Mart. Or Cabela’s. Or, better still, the gun show down at the local fairground where you can buy an assault rifle without the annoying inconvenience of a background check or a waiting period. Now to the worldwide cries of horror, and terror, and grief we can add those of San Bernardino, Colorado Springs, Roseburg, Chattanooga, Charleston, Isla Vista, Ft. Hood, Washington, DC, Santa Monica, Newtown. There is a kind of heart-breaking and ruthless justice in it.

Want to stop gun violence? Here’s another old, worn, misused, abused, and embarrassing word we, as a nation, might want to reconsider: repent.

1. The disagreement between the noun “wages” and the verb “is” is, in my opinion, an attempt to stay true to the Greek even at the expense of proper English grammar. Why they didn’t translate the word as “pay” and avoid this difficulty is beyond my linguistic pay grade.

2. For an intelligent and readable consideration of the writings of Paul that put his letters in their historical context, read The First Paul by Borg and Crossan.

3. For fifty years, Gordon Cosby was the pastor of Church of the Savior, headquartered in Washington DC. CofS was and remains an open, affirming, peace and justice church speaking truth to power in the nation’s capitol. I was a member of CofS for some ten years before moving to California.

4. http://www.nytimes.com/2015/12/26/world/middleeast/us-foreign-arms-deals-increased-nearly-10-billion-in-2014.html?emc=edit_th_20151226&nl=todaysheadlines&nlid=68670615

�LTk�~cu���ݹ

0 notes

Text

Kim Davis

Based on my experiences growing up, living and working in small, rural, southern communities, Kim Davis, the Kentucky county clerk who refused to issue marriage licenses to gay couples, does not represent the vast majority of rural, white, southern Christians. To allow her to become the face of the people in those communities will only further justify the almost constant assault on the fabric of small rural places that began at least by the end of WWII and probably has been going on to some degree since the Civil War.

Rural economies have been devastated by the systematic, government funded, university promoted destruction of local agriculture in favor of huge agribusinesses. Food grown in arid regions of California using government subsidized water and cheap immigrant labor is being shipped across the country on government subsidized highways to be sold in corporate supermarkets often cheaper than it can be grown and marketed locally. (NAFTA did exactly the same thing to small farmers in Mexico.)

In Kentucky, tobacco, the only crop from which a small farmer might hope to make a reasonable return on his labor, became the national whipping boy blamed for virtually every ill imaginable. By contrast, California’s drug crop, wine grapes, have been touted, flouted and trumpeted worldwide. As a person who’s suffered and recovered from additions to both alcohol and tobacco, I can assure you that the consequences of alcohol addiction are far and away, in every conceivable category, more damaging and destructive than tobacco. But it doesn’t take a statistician to parse the demographics of who drinks wine and who uses tobacco to expose the elitism and anti-rural bias that undergirds national preference, priority and policy.

Horrible as the coal industry is, once those jobs are gone, about the only employment in rural Appalachian communities will be working as an “associate” at Walmart – or something equally depressing. And once we environmentalist have saved the mountain tops from big coal, do you think for a minute we’ll give a rat’s ass for the people who call those hills and hollows home – rednecks and hillbillies? History has already answered that question.

Religion, never a very powerful, yet stabilizing force in small communities is being hounded like a trapped animal into smaller and smaller enclaves of influence until it seems quite possible that one day noise ordinances will forbid the sound of hymns leaking beyond the church walls.

Their right to bear arms is under attack and now gay marriage, something as unthinkable as polygamy just a few years ago, is being crammed down their throats.

Please don’t get me wrong. I hate tobacco; it’s a horrible drug. I despise the practices of the coal industry. I wish fervently we had atheists serving in government at the national level, and clearly I support gay rights, including marriage. These are vitally important issues to me.

But we must be aware that it is in rural communities and from those who share their values that most of our food comes. Think about that. And if that doesn’t sober you up, consider that small rural communities and those who share their values fill the ranks of our all-volunteer army with young men who are sent to kill and die for what increasingly seems like corporate rather than national interests. We might want to think about that before we hurl too many more insults southward. Because one day these young men, highly skilled in the art of killing with easy access to assault weapons, might decide they’ve had enough, enough of the cities calling the shots, enough of being belittled by overeducated snobs, enough of being demeaned and devalued for having hands that are dirty and calloused, enough of the constant assaults on their beliefs and values and take matters into their own hands.

And if that day ever comes – and God, I pray it doesn’t –I hope we liberals with all our intelligence will be smart enough to recognize, we helped create it.

*Read Wendell Berry’s “What Are People For” for a much fuller and more eloquent elaboration of these ideas.

0 notes

Photo

I have a monarch in my garden flitting about the milkweed plants, hopefully laying her eggs. Hours upon hours upon hours of work, hundreds if not thousands of dollars invested, much of it to try and help save this beautiful, tiny, orange and black creature dancing through my garden whose kind now number a tenth of what they did when I was a child. It is, in all likelihood, hopeless. Between a monarch – or even a million monarchs – and Monsanto’s money there is no contest. But I am commanded by my God and compelled by my nature – or is it the other way around? – I am compelled by my God and commanded by my nature to act in and for and out of hope; for who knows? Life is a miracle, and the odds are not always what they seem. And who’s to say that the meek who one day inherit the earth will necessarily be human?

0 notes

Text

Silly, Silly, Not-So-Silly Me

Recently I was telling a friend I hadn’t seen in a while about my year substitute teaching. When I told her how I had gotten more work than I actually wanted, she teased, “And you thought they might not hire you.”

As it turned out, I was wrong, silly me, to think they might not be willing to hire me because I’m transgender. Then again, what I know and what she doesn’t, perhaps can’t know, is that it might have turned out differently.

While there are laws as well as school district policies that protect my right to work as a transgender person, (laws and policies for which I am enormously grateful) I knew that should they not hire me, there would be virtually no way to prove it was due to discrimination. And there were good reasons for them not to. School administrators are busy people; they have a lot on their plates. When the list of subs is already adequate, why let someone into a classroom about whom the most irksome of parents might complain? No administrator in his or her right mind wants to deal with religious fundamentalists, and I, who grew up among religious fundamentalists, am the last person to blame them. School administrators are also – and I hope I will be forgiven if I am wrong – not known for being big risk takers, and I, by simply being who I am, am a risk.

Not only that, I must constantly live with the knowledge that all it takes is one parent of the right sort, one slip-up on my part, one innocent mistake, and things could go south quickly.

For example: Subbing jobs are advertised on a sub finding website where I can access them and either accept or pass on them. I passed on several jobs for a co-ed P.E. teacher, because early on I learned that these jobs required going into the girls’ locker room, and that felt like territory I would do best to avoid. Then one day when I was working a half day gig at a middle school, I got a phone call from the district’s person in charge of finding subs desperately looking for someone to cover P.E. that afternoon. Since I was already on site, would I be willing to take it? What could I say? This was the very person I most wanted and needed to please, the person with the power to decide where I was ranked on the roster of subs. “Sure,” I said. “Can you also be there tomorrow?” she asked hopefully. “Sure,” I repeated, trying to conceal the hesitation I felt.

Now let’s be clear. I have no problem with the girls’ locker room. While yes, they have bodies for which I would have gladly given my right arm, I am not interested in their bodies. The problem with the girls’ locker room for me is that one of the consistent claims made by fear mongering transphobes is that the main motivation of male-to-female transsexuals is that we want access to places like girls’ locker rooms. Apparently our sick little minds are intent on…well, I’m not sure what they imagine we are intent on, but in their narrow little minds, it is no doubt terrible. Now mind you, I am old enough now to be these girls’ grandparent. Not only that, my sex drive was all but obliterated by the miracle of modern medicine over fifteen years ago when I was merely old enough to be…well, in truth, I was still old enough to be their grandparent, albeit a youngish one. In fact, it’s hard to imagine anyone safer in a locker room full of girls than me. Still, what I know from hard experience is that reason is always one of the first casualties of bigotry. And my greatest fear was not just that some parent might complain, but that I would never hear about it, and yet, I would suffer the consequences nonetheless.

Now maybe I could go and talk to the people at the district about my concerns (they are, after all, lovely people), but what are they going to say other than what the policy is? And so far as I know, they have consistently, conscientiously and perhaps even courageously been faithful to that policy of nondiscrimination. Do I really want to question that? Let sleeping dogs lie.

These are the questions, the concerns, the anxieties with which I and others like me must live. They are unavoidable, and they have very real consequences. I passed on jobs that I was perfectly capable and qualified to do, jobs that paid real money. Knowing the circumstances into which we were about to enter but not knowing what the outcome might be, when Jan and I refinanced the house, we did an interest only loan to keep the payment as low as possible just in case I couldn’t find work as a transwoman. That decision – a bad one as it turns out – has cost us thousands of dollars.

In hindsight, these decisions seem foolish, even paranoid, but what I know that my friend who is a member in good standing of the dominant culture cannot is that while she might call me silly, I fear the reality is I am anything but. My hope, of course, is that she keeps on being right, and I get to keep on being silly, silly, not-so-silly me.

Reply to: [email protected]

0 notes

Text

Beautiful Reader of Poetry

March 20, 2015

I’m subbing in 9th grade English. The topic is poetry. The enthusiasm for the topic is hovering somewhere around…oh, I’m guessing – a negative 20. I am guiding them through a worksheet left by the teacher on which they are to analyze several poems, when I notice a sullen, heavy lidded Latino sitting on the floor, earbuds firmly implanted, doing nothing. Not knowing his name, I call, “Hey you, in the back.” He ignores or can’t hear me. A fellow student nudges him. He looks up. I pantomime removing the earbuds. He complies. “Are you getting this?” I ask harshly. He shrugs. “Move over here,” I order in my “don’t f#*k with me” voice, indicating an empty desk. With slow deliberation, he unfolds himself and moves. I continue. The next poem we are to analyze is by a Chilean poet. On one page the poem is written in Spanish, on the opposite page is the English translation. “Will someone please read the poem in Spanish?” I beseech, hoping one of the Latino kids will volunteer. Instead, a tall anglo boy who’s been giving me trouble and clearly cares not a whit for poetry raises his hand, but I can see he’s just going to make a joke of it. “No, someone who really knows the language,” I insist. In the back, Mr. Badass half-heartedly raises his hand. What now? I wonder, but “Thank you,” is what I say. With some effort, I silence the class. He begins to read in a soft, clear voice, the Spanish rolling off his tongue like sweet water from a spring. When he finishes, he looks up. Our eyes meet, mine now full of admiration, and I say genuinely, “Thank you. That was lovely.” Then quickly, before the class clown can break the spell, I ask, “Even if you don’t understand the words, do you hear the rhythm?” In unison the class nods. “What feeling does this poem evoke in you?” I ask, hoping to ride this wave of interest and attention as long as possible. In the back, Mr. Badass who has now transformed himself into Beautiful Reader of Poetry says, “Peaceful.” “Oh yes!” I exclaim, gesturing enthusiastically. “It’s like a lullaby, isn’t it?” From this point on, I don’t care if he fills out the damn worksheet or not. This boy has poetry where it belongs – in his soul.

Reply to: [email protected]

0 notes

Text

Toward Psychic Equilibrium

Last week the school year officially ended. Averaging a little over twice a week, I subbed over a hundred times in a variety of schools from grades 3-12. Most of my experiences were good, some were great, a few were awful.

While I need the money, I have at least one other way to make money that’s easier, considerably less stressful, and even pays a little better. But I like teaching; I miss it; and every now and then as a sub I actually get to do it. I also enjoy being around kids…well, most of the time; plus I have something to offer them no one else can, or, at least, no one else does.

The poet Adrienne Rich has said, “When someone with the authority of a teacher describes the world and you are not in it, there is a moment of psychic disequilibrium, as if you looked into a mirror and saw nothing.”

As a sub, I rarely get to describe the world to the students seated before me. I am bound by what the classroom teacher leaves me. What I do have to offer is an up-close and personal experience with an out, open and visible transperson. And I offer this up-close and personal experience at a time in their lives when they are most apt to be homo and transphobic.

While this can be rough on me at times, I think it’s universally good for them. In the abstract transgenderism can seem so weird – so queer. But in the flesh I’m neither weird nor queer acting, and while, yes, they can make of me an exception, still, I think my presence in the role of a teacher normalizes queerness in a way that might take the edge of fear and hate off it. I hope so.

I also think it’s important for children like me, LGBTQ children (Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Questioning) to see someone like them in front of a classroom. Here’s why.

I had been warned it was a difficult class, and after the first fifteen minutes, it was clear the warnings had not been exaggerated. I felt like I had been put in charge of a wagon hitched to 30 preadolescent, untrained thoroughbreds who, with only two reins, I was supposed to get to pull together in a direction they had no intention of going. Under these circumstances, education is little more than wishful thinking; keeping the floor clean of blood is about the best you can hope for.

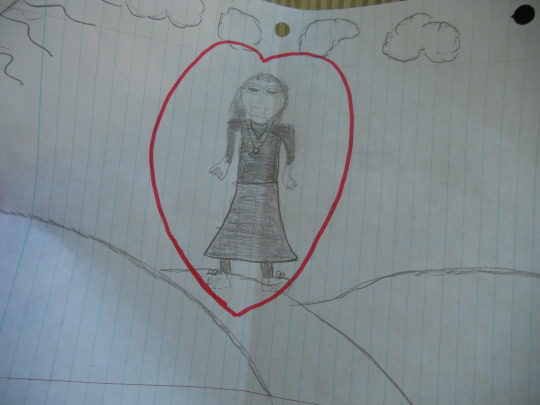

In this class was a boy I shall call Jackson. Jackson is one of those boys who might as well be rainbow colored, because everything about him rings out “gay!”. It didn’t take long for Jackson and me to discover one another. Knowing how hard middle school can be on gay and gay perceived students, I hovered close, made conversation with him and smiled a lot in his direction. I also told him more than once to stop talking to the girls at his table and to get to work. On one of my passes around the room trying to make sure everyone was on task, Jackson gave me a drawing. “I wish you were my teacher,” he said quietly, cutting his big brown eyes up at me coyly. The drawing was of a woman - me - enclosed in a red heart.

Now, while it’s true Jackson, unlike me at his age, gets to see plenty of out, happy, successful gay people in the world most of them exist in the media and few to none in the world of K-12 education. So standing in his classroom, in the role of his teacher, speaking with the authority of a teacher, I get to say (though not in words) that who I am and, by extension, who Jackson is is okay. We are in the world; we are part of it; and we belong.

There are parts of subbing that are hard. Even good days carry their own kind of pain. But even after a very difficult day with a very difficult class, I look at this picture hanging on my fridge, and in my mind see the face of that adorable child, and I know regardless of what it costs me, he is worth it. He and all the others like him are worth it. Whenever I can, however I can, as long as I can, I want to be a teacher who with the authority of a teacher holds up a mirror in which these children see themselves, beautiful, valuable and worthy of all the best life has to offer.

Reply to: [email protected]

�

0 notes

Text

Crossing Borders - a sermon

For many years I was a teacher. I loved teaching, and I miss it. Now, to supplement my retirement, I substitute teach at a variety of schools in Petaluma. It’s good for me, and I think it’s good for the kids to have an experience with an out, visible and reasonably healthy transgender person, likely their first, or the first of which they are aware.

Back in the fall, I subbed in a high school English class. It was my first time in this class and only my second at this school. As I stood before the class waxing eloquent about the importance of verbs, a boy on the front row, slouched down in his desk, chewing on the eraser of his pencil eyed me suspiciously. Now, getting eyed suspiciously is nothing new for me, but this guy was not letting up. He glared at all 6’2” of me like maybe I was the proverbial wolf in sheep’s clothing.

At lunch I walked across the crowded campus to the teacher’s lounge to use the bathroom and refill my water bottle. On my way back, as I approached a table of kids eating outside, I saw their heads turn in unison to look at me, then, seeing me notice, turn quickly turn away, laughing, smirking, sharing OhMyGod looks with one another.

Lord knows how many Face Book posts I have been the subject of, how many times my photo has been surreptitiously taken, on how many occasions I have been the topic of conversations. Some I know of.

Now, even if some part of me enjoys attention, none of this is pleasant; yet, every day since coming out as transgender I get to cross borders, and this, it seems to me, is what each of us is called to do whenever we can, because, in the words of Dr. King printed in your order of service, “We will either learn to live together as brothers (and sisters) or we will perish together as fools.”

And so, I make it a point to try and engage with the young skeptic in the front row; I make eye contact; I move close to him; if possible, I find some way to speak to him, ask him a question that requires a reply. He might not let me cross his border, but I want him to know that I want to, that I think he is someone worth getting to know.

With the group at the table I do the same. I intentionally walk close to them. I catch an eye and smile pleasantly, yet, also knowingly. “I’m here,” I say wordlessly, “and I know you see me, and that’s okay.”

I make it a point to cross these borders whenever I can – gently, respectfully, good naturedly – and sometimes, though not always, the borders disappear and we connect, person to person, human to human.

Of course, this is not what I want to do. What I want to do is move away or at least look away, somehow distance myself from the ridicule of others. Had I the luxury, I might very well spend my days tucked safely inside my snug little study, writing and reading and thinking. Given my druthers, I’d hang out with people like you, people who don’t care that I’m transgender, maybe even like it that I am. I’d prefer spending my time in funky little coffee shops in cool little towns talking and debating with people who share my interests, my passions, my values. That’s what I want to do, and I bet with slight variations of details, that’s what you want to do, too. It’s enjoyable spending time with like-minded people, and there’s nothing wrong with that. We just don’t cross any borders that way.

Recently, through Face Book, I reconnected with a woman I knew when I was a young, handsome, promising Southern Baptist minister, and she a lovely teenage member of the youth group in the church where I served in Jackson, Mississippi. The renewal of this old friendship is especially significant to me, because I know the borders Susan had to be willing to cross to reach out and reconnect. I imagine it was not easy for her, having known and loved me as a man, to accept me now as Meredith. Also, she and her husband spent many years as Southern Baptist missionaries to Uruguay, and Susan remains a conservative Christian, putting us often on opposite ends of the theological spectrum. She’s also a vocal opponent of abortion and a woman’s right to choose, putting us on opposite ends of the political spectrum. So to maintain this friendship, we have both had to cross borders, and that’s part of why I value it. I want Susan in my life, because, while we love one another, we don’t agree.

Because of her convictions as a Christian, her years in Uruguay and the fact that she has adopted children from there, Susan has great sympathy and compassion for undocumented immigrants in this country. From her posts I know that she frequently struggles with her conservative church friends trying to get them to cross their borders of fear, prejudice and xenophobia to connect compassionately with the immigrant community. And she has been bold and brave in her confrontation of her community – and it has cost her.

Recently, I watched the movie “Pride.” If you haven’t seen it yet, I highly, highly recommend it. Set during the reign of Margaret Thatcher in England, it’s about a group of gays and lesbians who, realizing that they share common foes in Thatcher, the police and the conservative press, decide to lend their support to striking coal miners in Wales. As you might imagine, Welsh coal miners are not noted for their support of gay people. This true story not only gives a dramatic example of what crossing borders looks like but what it costs, because the efforts of these gay and lesbian activists put them squarely between the prejudice and hostility of the miners for gays and the prejudice and hostility of the gay community for the miners.

And, of course, no talk about crossing borders can ignore those who have, in search of a better life, crossed, at great cost, the very real border between the U.S. and Mexico. Regardless of how you feel about undocumented immigrants or what you think should or should not be done about their legalization, no person of conscience can get to know them and hear their stories without feeling sympathy and compassion.

But rather than focus on immigrants crossing our border, I think the focus would better be put on our crossing of the southern border, especially our crossing as a nation. When the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) opened the borders between Mexico, the U.S. and Canada one of the things that happened was heavily subsidized U.S. corn and other staples poured into Mexico, causing producer prices to drop and leaving small farmers in Mexico unable to make a living. Some two million have been forced to leave their farms since NAFTA while at the same time, consumer food prices rose, notably the cost of the omnipresent tortilla. No longer able to make a living farming, where do you imagine many of those farmers fled? Since the agreement went into force in 1994, Mexico’s annual per capita growth flat-lined to an average of just 1.2 percent -- one of the lowest in the hemisphere. Its real wage has declined and unemployment is up. The terrible violence in Honduras and Nicaragua which led to thousands of children fleeing to the U.S. can reasonably be traced to our deportation of violent offenders to those countries. Now while some of the consequences of NAFTA are arguable and correlations are not the same as causation, it seems to me we as a nation need to take a long look at how we have contributed to the problem of illegal immigration. Otherwise, we are going to be like the guy who accidentally shot a hole in his boat. As the boat filled with water, he decided that to drain it, he’d shoot another hole. We are never going to solve the problem of immigration until we acknowledge the ways we have and are continuing to create it. Then, rather than building higher and more sophisticated walls – which historically have never worked – we need to begin imagining and creating ways to improve the economic, social and political conditions south of our border. The Obama administration has made some welcome, albeit tepid, moves in that direction recently. Lord knows what we could do if we diverted the money we are currently spending to create jihadists in the Middle East and instead, invested it in creating better living conditions for our southern neighbors. Talk about a win/win.

This, it seems to me is a prerequisite to any serious immigration reform, especially one that talks about a path to citizenship. I am worried we may be approaching a perfect storm. If this drought continues, creating greater hardships, if wages for lower class Americans continue to decline or stagnate, if economic gains continue to go almost exclusively to the top 2%, widening an already obscene wealth gap, the anti-immigrant demonstrations we’ve seen in parts of Europe and most recently, South Africa, could easily erupt here. We don’t have the luxury of continuing to flounder about in the Middle East while ignoring the needs of our closest neighbors.

There are many ways to cross borders.

For instance, sometimes you just find yourself on the other side.

- When I came out, Caleb, my son, was 16 and Lia, my daughter, 14. Virtually overnight they went from being easy going, popular members of the high school “in” group to having to deal with all the stresses suffered by gay and lesbian children their ages. They didn’t ask to cross that border, but by choosing to stay in relationship with me, they had to. And all these years later, they still have to.

-The organization PFLAG is specifically for people who one day found themselves on the other side of the gay/straight border when their son or daughter came out as gay or bisexual or transgender.

Now anyone can cross borders, and sometimes it’s surprisingly easy. A friend of my partner, who is very white and not someone I would describe as particularly liberal, enrolled her children in a bilingual school in Petaluma. Her older daughter, Julia, now a third grader, was recently selling Girl Scout cookies in Friedman’s with some of her friends. As a Latino man walked by on his way to the check-out, they asked if he wanted to buy some of their cookies. “No, no,” he said, and he hastened to get away, as if the prospect of dealing with a group of little girls was too much for him. Then Julia spoke up, but this time she asked him in Spanish. Julia’s mother reported that, hearing this little white girl speak to him in his native tongue, the man turned on his heel as if he had been hooked. Carrying out the transaction in Spanish with Julia, he bought several boxes, and a border was crossed.

Sometimes it’s hard at first, but then, gets easier. Just this past week, I was back in the high school English class I talked about earlier. This was probably my fourth time in that class, and, though I didn’t remember his name, I decided to see if I could find the boy who had been so suspicious the first time. He had migrated to another seat, but I think I found him. When the period was just about over and the kids were getting their stuff together and milling about, he walked over to where I was sitting organizing papers and struck up a conversation. For the last couple of minutes of class, we chatted amiably – person to person, human to human.

Sometimes, however, it can cost you dearly.

In the January 29 issue of the N.Y. Times there is a story about two Oakland high school boys, Richard and Sasha. In November of 2013, their lives intersected tragically. Richard, an African-American, lived in East Oakland, an area of grinding poverty and frequent violence. His mother, wanting something better for her son, sent him to a high school across town with a better, albeit not great, reputation. Sasha commuted an hour to a high school in Berkeley that caters to “bright, quirky kids.” Sasha identifies as “gender queer” neither boy nor girl, man nor woman. (Out of respect, I will henceforth refer to Sasha by using the non-gender pronoun xe, which I can assure you feels as odd to me as it does to most of you.) That November day of 2013 as Shasha rode the bus home, xe, who is clearly male and makes no attempt to hide that, was wearing a skirt. There are few borders so sacred, so inviolable as the borders separating the genders, and that is especially true for the borders that delineate what it means to be a boy or a man. By daring to wear a skirt, Sasha was illegally crossing all the gender borders. Richard and two friends were also riding the bus that day, and when Sasha dozed off reading Tolstoy, Richard took a lighter, and after repeated attempts, set Sasha’s skirt on fire. Sasha spent the next three weeks in the hospital being treated for 2nd and 3rd degree burns. Richard, age 15, was scheduled to be tried as an adult and faced possible life in prison.

This incident brings to mind the quote, also in your order of service, by Thich Nhat Hanh: “Someone who is angry is someone who doesn't know how to handle their suffering. They are the first victim of their suffering, and you are actually the second victim. Once we can see this, compassion is born in our heart and anger evaporates. We don't want to punish them any more, but instead we want to say something or do something to help them suffer less.” By this accounting, Richard was the first victim of the suffering that is the daily fare of so many young men of color, while Sasha was the second – or perhaps third or fourth or fifth. I want to have and to hold this perspective of Richard and his friends, to understand their cruelty, to see and to feel it as an expression of their own victimization. And in my head, I can, but I will admit to you I’m having trouble getting it in my heart.

By the end of the long ordeal, after the plea bargain and the sentencing, Sasha’s mother told the Times reporter, “I wish it had turned out differently for Richard. We got Sasha back. But poor Jasmine (Richard’s mother). She lost her son for years.” They hadn’t expected to be so moved by seeing Richard’s face again.“I just had this wave of emotion at how young he looked,” Sasha’s dad said. “He just looks like a kid.” And these people who had every right to draw borders and erect walls, chose not to.

On the recent 50th anniversary of the Selma Voting Rights Movement, Unitarian Universalists were reminded that 50 years ago, Jim Reeb, a Unitarian Universalist minister and pastor was murdered in Selma, Alabama, by white segregationists for having the courage to cross the border between the races.

And yet, the cost of refusing to cross borders is infinitely higher. The entire Middle East is a tragic example of what it costs when people refuse to cross borders. And like Tar Baby in the Uncle Remus stories, the more we get involved in their dance of hatred, the stucker we get.

Nor are the borders all out there. We too have our borders.