Text

Flash Back: Slavery and the black lens in Get Out

Plot description below: If you are avoiding spoilers, fall back. If you don’t mind me focusing your view of the film, carry on.

In the 2017 movie Get Out, Jordan Peele takes the thriller genre and turns the camera on the world through a playful black lens. I am using “black lens” to talk about a collective identity, consciousness, and, in this case, humor rooted in cultural references and histories. Seeing the world through the eyes of a black director and protagonist is a rare, powerful, and funny thing. I had to see it twice... to look for the hints along the way.

The first time, I went to see it opening night in Hollywood and it was a decidedly black viewing experience for me. I had a friend put it this way – the best part of the movie was the reaction to it by other black people in the movie theater. The audience was a mixed crowd but the humor rooted in black cultural references was heard loud and clear in the laughter and commentary throughout the film. Responding to what we hear and see on the screen is part of the party. The humor of the film and the audience’s riffed reactions to it served as a salve for me while viewing a movie about psychic and physical terror.

A memorable example is when the protagonist, Chris Washington, a photographer in a white New England suburb, realizes that he is neither the first, the second, nor the third black person his white girlfriend Rose has dated. Chris is flipping through physical photographs of different black people posed lovingly with Rose Armitage, all unknowingly being lured into her family’s elaborate trap. After a few photos, someone behind me started narrating names for each new boo as he went through the images. It was something like “Tyrone, Jamaal, Sindarius...,” you get the idea. This improvised commentary provided comic relief for people within earshot and we definitely laughed. Humor was especially necessary because Get Out deals with such a frightening and familiar subject for black American viewers - the exploitation of black bodies. I realized later that seeing the photos of each black person as themselves - before their terrible transformations - was powerful. Once their bodies were owned, they would not be photographed; especially not with flash.

After seeing it once, I read and thought about the ways slavery is invoked in the film, especially in the scenes when our hero is trapped in the basement of the Armitage house. Chris is bound to a chair, with straps around his ankles and arms; the sound of which ring true to the movement of shackles and chains in movies about slavery and the slave trade. The imagery of Chris strapped into place is also a reference to the electric chair, invoking continued black subjugation through mass incarceration. The electric chair foretells the certain death of the occupant, and Chris faces the threat of (a sort of) death in the enslavement of his body to the will of the chosen white bidder. He also picks cotton, a trope in images and stories of black American slavery; and this act helps save his life. After scratching through skin of the chair over time, he picks out the stuffing and puts it in his ears, blocking out the hypnotic preparation for surgery he sees and hears on the television screen in front of him.

While strapped to the chair, coming in and out of consciousness, Chris is presented with two types of video. First, there is old footage of three generations of the Armitage family, with Rose and her brother Jeremy as children, their mother and father looking younger, their grandmother, and the mastermind grandfather explaining the process. This video was another moment of black humor my first time seeing it. There is a long shot of the grandfather walking onto the screen and his stride, posture, and clothing are absurdly and hilariously white – a type of performance one might do when mocking whiteness. Despite being in one of the tensest moments of the film, there is a comic relief in way the white domination is portrayed.

The other video - a live, interactive feed of the white man who won the auction for Chris’ body - did not invoke laughter. Chris met Jim Hudson earlier in the film, at “grandpa’s” gathering at Armitage home where white people and couples came to view and place bids on Chris Washington without his knowledge. The man is blind and an art dealer, and Chris has heard of his gallery. When they first meet, Hudson admits that art is a strange business for a blind man and says that his assistant describes art to him in great detail; and that he knows Chris’ photographic work. In that moment, Hudson tells Chris that he has a “good eye.” When Chris encounters Hudson again on the screen in the basement, the blind man says he bid on his body specifically for his eyes. In Chris Washington, Hudson envisions himself living a life where he can not only see, but have an eye for art. The form of exploitation Chris is being prepared for, and that all the people in the photographs are being subject to, is one where their bodies, including their eyes, are no longer their own.

The Armitage scheme involves the capture of a black person, through deception and abduction. This is followed by hypnosis performed by Rose’s mother. We learn early on that Missy Armitage hypnotizes people to stop smoking. In preparation for the horrific surgical procedure, she mentally paralyzes the person, relegating their conscious mind to what she refers to as “the sunken place.” After that, they are kept in the basement of the Armitage home and forced to view videos before Rose’s father, a neurosurgeon, performs a double lobotomy and transplantation. Late in the film, we see Dr. Dean Armitage cut open the skull of Jim Hudson to take out his brain and surgically place it in Chris’s head. In the Armitage family business, they sell stolen black human beings to serve as the physical vessel for the brain and will of a white owner. The black body remains with part of its own brain intact, but that body functions under the submission of a white buyer’s mind. As we see in many moments of the film, however, the consciousness of the black person is never fully extinguished.

The black character who makes the disturbing outburst that reveals the resilience of the black mind is the first person we see in the film. In the opening scene, Andre Hayworth, a young musician from Brooklyn, New York is walking down the street at night in a suburban neighborhood where he feels uncomfortable and (rightfully) thinks he is being followed. Someone gets out of a car, puts him into a chokehold until he passes out, and then dumps Andre’s body into the trunk. We later find out that his abductor is Rose’s brother, Jeremy Armitage. Andre appears again later in the movie when we see him through the lens of Chris’ camera at the mostly white gathering; the auction party where he meets Hudson. Upon spotting a black man, Chris approaches and says it is nice to see another brother at the party. Chris is quickly and thoroughly disturbed by the other black man’s performance: the failure to pick up on black social cues, the apparent relationship with a white woman more than twice his age, and the out-of-place clothing - including a funny hat hiding the scar tracing the circumference of Andre’s head. Even without knowing about the awful scar, Chris decides to document this strange black man with a picture and send it to a friend back in New York City. While attempting to surreptitiously snap the smartphone photo, the camera flashes… and a spell breaks. Andre’s eyes appear to lose a sort of animation, he bleeds from the nose, and returns to himself. With the flash of the black photographer’s camera, Andre’s own mind once again animates his flesh, and he immediately charges toward Chris, grabbing him and urging him to “Get Out! Get Out! Get Ouuuttt!” Chris knows that this episode is not a seizure as Dean and Rose claim because he recognizes the brother he just unknowingly and temporarily emancipated.

When I saw the film a second time, there wasn’t the same raucous reaction and laughter that gave me so much life opening night. I went with a friend one evening after work over a week after it was released and the theater was much whiter, quieter and hesitant to laugh. We walked away in a serious mood discussing the family, community, and operation in the film. She opened my eyes to the fact that smoking is strongly discouraged before surgery to lessen the possibility of complications. Rose throws Chris’ cigarette out of the car window on the way to the house; upon arrival, Dean discourages him from smoking; and that night Missy hypnotizes him to be disgusted by cigarettes. These small details related to the surgical nature of the process in the film disturbed me.

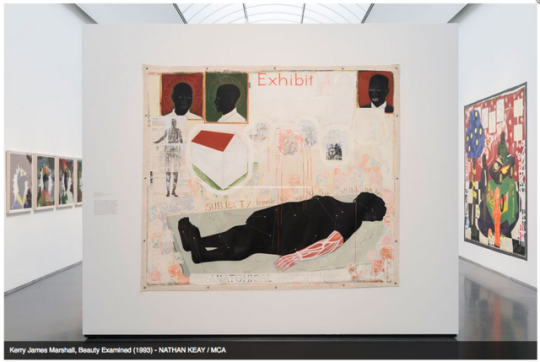

Soon after, I saw an exhibition of work by artist Kerry James Marshall, and was struck by a painting called Beauty Examined. In it, a black woman is laid out on an examination table and her body is surrounded by notations and measurements pointing to different parts of her body. The surreal scene also has such elements such as muscles and cut-through views of organs. Prominent text at the top reads faintly “Exhibit A.” Floating just above her body reads: SUBJECT / female blk, age 30, 5’3, 148 lbs, blk ha(ir).” There is also two shots resembling a mugshot of another figure at the top of the painting, referencing the use of photography to criminalize black populations. The woman on the table is looking away, fixed in a serious expression. This piece helped me realize what was so disturbing in thinking about the surgical part of enslavement in Get Out: cutting open black people’s bodies against their will is nothing new.

As Harriet Washington documents in Medical Apartheid, modern gynecology was built upon observations and experimental surgeries practiced on enslaved black women in the United States. Credited with pioneering techniques and knowledge in the field of gynecological surgery, physician and slaveholder James Marion Sims restrained his black female slaves and repeatedly sliced open and sewed back together their vaginas, most often without anesthesia. These surgeries were extremely painful and the black women who were experimented upon protested violently. Dr. Sims and others justified their actions with the belief that black people were not fully human and therefore, incapable of suffering. This meant there were no moral consequences for experimenting upon and exploiting their bodies.

The movie Get Out reverses the traditional lens of Hollywood cinema, which is usually positioned from a white and male perspective. The film is frightening because the community and form of enslavement it imagines is twisted yet familiar considering the history of slavery and medical experimentation on black people in the United States. Peele makes moments of laughter and serious contemplation possible by presenting a scenario that is outrageous but not altogether unfeasible to the viewer who is aware of the intricate and intimate forms of subjection that black people have endured throughout this nation’s history.

Positioning the viewer from the perspective of a black figure, Get Out also references another tendency in American history – the emancipatory uses of the camera by black people. As Deborah Willis and Barbara Krauthamer bring to light in their book Envisioning Emancipation: Black Americans and the End of Slavery, photography was a new and powerful tool in the final decades of legal slavery in the United States: “the intensifying national conflict over slavery and black freedom played out through competing campaigns of photographic imagery” (3). On one hand, slaveholders and scientists made images of enslaved black people as evidence of their supposed inferiority and to document them as property. On the other hand, black people began making images of themselves that presented an alternate narrative.

As photographic technology became available in black and white en masse, photographers and photo studios began popping up across the country. Many professional photographic practices, among white and black entrepreneurs, created images for Civil War soldiers and families of some means. Some of these photos were studio portraits of individuals and families with dignity –in uniforms of the Union, wearing the finest dresses and hats, and teachers with school children at newly-formed schools. Many portraits included people posed with things like books, pocket watches, and musical instruments to convey education and rising status. These images expanded the visual archive of blackness to include family, community, and everyday life; countering the dominant white gaze that had fixed black people as less than human. In a context of dispossession, black people used photographs create a sense of belonging and envision beauty in blackness in the first decades after emancipation.

In Get Out, the camera is key to Chris maintaining his freedom through really seeing black people and bringing them back into their bodies by taking flash photos of them. Through the lens of his camera at the party, Chris notices a black woman (enslaved to grandmother Armitage) strangely admiring her face in the mirror, furthering his suspicions that something weird is happening among black people at the Armitage house. The flash of the camera on his phone brings Andre back to life, and the photo that results helps him confirm his suspicions when his friend back in New York recognizes Andre as a brother from Brooklyn. Flipping through photographs of his girlfriend with black people she has tricked and trapped solidified that all the black people around him are not fully themselves. And finally, when Chris faces being shot by Rose after discovering the grand scheme and killing the rest of the family to escape, Chris again uses the flash to emancipate the black man who is enslaved to grandfather Armitage. When the man returns to his conscious self, he shoots Rose and then fires the gun through his own body, killing the brain that is not his own. In this moment, the man finds freedom in death rather than risking being returned to the sunken place and living in a horribly altered physical state. It is through seeing other black people for who they are that Chris eventually walks away with his body and mind intact.

Get Out is a thrilling, humorous, and painful movie created through a black lens. Jordan Peele uses both humor and horror to reference the ways the beliefs and tactics of white racism are passed down through generations, as well as the legacy of black people claiming agency and freedom in contexts of domination through images and the camera. In a world where we come to know ourselves and our reality through images, the movie takes the viewer to an alternate reality that is an extreme and contemporary version of things we have already seen happen in this nation.

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

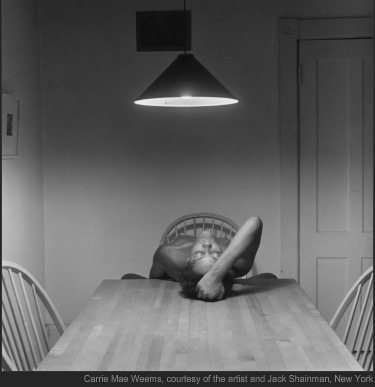

"I’m thinking that it’s not about social problems, that it’s about social constructions. [My] work has to do with an attempt to reposition and reimagine the possibility of women and the possibility of people of color, and to that extent it has to do with what I always call unrequited love." - Carrie Mae Weems, visual artist and 2013 MacArthur Fellowship recipient

0 notes