#Arahsamnum 2021

Text

Arahsamnum 2021: Kilili

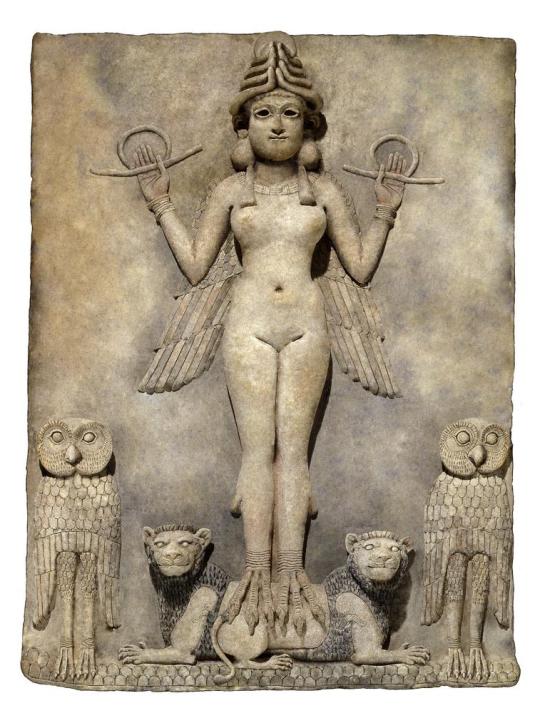

Ninkilim, the deified mongoose, was hardly the only deified common animal in the mesopotamian pantheon. Another example is Nin-ninna (“goddess of the owl”), better known under the name Kilili.

By far the most notable thing about her is that according to the most recent studies on the matter she might be the puzzling figure on the Burney relief. How come? And what was Kilili’s role in Mesopotamian beliefs? Answers await under the “Read more” button.

Burney Relief (British Museum)

Obviously, the most laughable is the identification of Miss Burney Relief as “Lilith” - it is somewhat hard for a figure who was only really given a coherent description in a humorous medieval Sepherdi work to be depicted on a cult relief from the Old Babylonian period. Even her distant linguistic “ancestors” don’t fit the bill, as purely demonic entities such as lilitu or ardat-lili by principle had no cult. Ereshkigal, proposed frequently, had no association with lions and played next to no role in cult, with most of the exceptions being late and connected to Nergal; while Ishtar, as a major deity, would not be depicted with animal body parts.

However, Kilili, as noted by Frans Wiggermann, an Assyriologist renowned for his studies of Mesopotamian demonology, fits perfectly: as a minor goddess she doesn’t necessarily have to look fully human (bird feet), and similar shape is well attested for various minor female figures of similar character, such as personifications of winds, periods of time or emotions (like Niziqitu, “grief”). Kilili is also basically the only deity whose presence might justify the inclusion of owls, uncommon in Mesopotamian art - the owl was regarded as “bird of Kilili,” and she could herself be described basically as a deified owl, as stated above.

According to the god list An-Anum, Kilili was one of the 18(!) messengers of Ishtar; these are to be kept separate from Ninshubur, whose functions were considerably more complex. Curiously, with the exception of Kilili and another similarly minor figure, Bariritu, most of said messengers do not appear outside god lists. Association of major gods with partially animal creatures wasn’t uncommon - while this is entirely personal speculation, perhaps the “bird women” like Kilili fulfilled such a role for Ishtar, much like scorpion men did for her brother Shamash, or the mushussu for a multitude of deities?

While more detail on Kilili’s character is not available in known sources,, her frequent “collaborator” Bariritu apparently was regarded as an instrument of Ishtar’s wrath, and in one case she’s described as serving as representative of some unspecified evildoer to doom him.

Curiously, in one case Kilili is attested in association not with Ishtar or variants thereof, but rather with Gula, the default name of any medicine goddesses in later periods of Mesopotamian history. To my knowledge no attempt has been made to explain this.

Further reading:

Kilili (Reallexikon der Assyriologie) by F. A. M. Wiggermann

Some Demons of Time and their Functions in Mesopotamian Iconography by F. A. M. Wiggermann

The Mesopotamian Pandemonium by F. A. M. Wiggermann

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

Arahsamnum 2021: Gilgamesh

You might be justifiably surprised by the presence of Gilgamesh among the figures I’m covering - after all, he’s hardly minor, if anything an argument can be made that he’s one of the only Mesopotamian figures to actually have some presence in popular imagination today. While that’s true, I want to focus on a side of this figure which is very rarely discussed - Gilgamesh as a minor underworld god. Worry not, though, more “mainstream” topics will be covered too, including a text indicating the existence of a scenario in which Gilgamesh and Enkidu were eventually reunited.

Read on to learn about Gilgamesh’s fate after the events of the epic.

Our story begins in the Ur III period, just like many other stories covered in this series of posts - it was a really good time for Mesopotamian religion and literature, evidently. One of the peculiarities of this era was the sheer enthusiasm the Sumerian rulers, especially Ur-Namma and Shulgi, had for Gilgamesh.

While he’s already known from older sources, it is evident that his popularity skyrocketed thanks to these kings. Not only the stories about him which were eventually forged into the epic we know now were in wide circulation, the kings regarded him as their “friend” or even “brother” and regarded him as a god. The deified Gilgamesh evidently had some degree of popularity among commoners too, as he shows up in personal names such as Ur-Gilgamesh.

The character of Gilgamesh the hero is well known, but what was Gilgamesh the god like? Rather surprisingly, he was an underworld deity, something which might seem odd to us considering the themes of grief, loss and joys of earthly life well known from the Epic.

The standard view was seemingly that Gilgamesh after passing away became an underworld judge. At least one source states that he received this position from the sun god Shamash, one of the deities of justice par excellence. However, other traditions existed too - for example, one incantation lists Gilgamesh as the ferryman of the dead, in this context grouped with Namtar, Ereshkigal’s sukkal (vizier) and Bidu (the gatekeeper of the underworld). Death of Ur-Namma instead presents him as a king of the spirits of the dead, though as the gods normally envisioned as being in charge still appear in it, he presumably still had to answer to them.

Yet another tradition associated Gilgamesh with Dumuzi and Ningishzida, two gods who were believed to spend part of the year in the underworld. Dumuzi is well known, but Ningishzida, as a more obscure figure requires a brief introduction: he was the son of Ninazu, himself a puzzling underworld god, and had a wide variety of functions, being a god of the underworld, of vegetation, and seemingly all around a reliable deity. To my knowledge there is no known explanation for his association with Gilgamesh, though. Curiously, a celebration associated with this trio apparently involved wrestling, possibly meant to evoke the fight between Gilgamesh and Enkidu.

Also, The Epic in it most famous form technically does hint at Gilgamesh’s underworld role and even brings up Ningishzida. The hero’s mother Ninsun makes cryptic references to her son being fated to dwell where Ningishzida and Irnina (personified victory, here presumably Ningishzida’s serpentine courtier and not epithet of Ishtar) do.

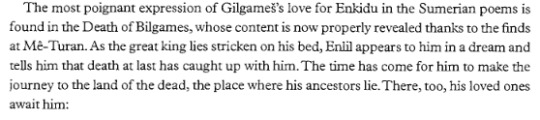

Last but not least, apparently a belief that Gilgamesh was reunited with Enkidu in the underworld also existed; I will quote A. R. George (book linked below; p. 141-142) here instead of summarizing it myself:

Following this poem, it’s arguably possible to see Gilgamesh’s cultic role as an unexpected happy ending of the famous epic. Was that the intent of the ancient authors, though? Hard to tell.

Further reading:

The Babylonian Gilgamesh Epic: Introduction, Critical Edition and Cuneiform Texts by A. R. George

Nin-ĝišzida (Reallexikon der Assyriologie entry) by F. A. M. Wiggermann

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

Arahsamnum 2021 finale: Enmesharra (Halloween special)

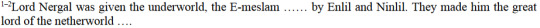

A god fighting a monster identified as possible depiction of Enmesharra by W. G. Lambert (via A. R. George’s Nergal and the Babylonian cyclops - which interprets this work of art differently)

After a bit over two weeks, the series draws to an end! The final figure to be covered is Enmesharra, and I think it’s fair to say I saved the best for last.

As a cursory online search can show, Enmesharra is incredibly obscure today - despite being attested from the 3rd millennium BCE all the way up to the Parthian period! And not exactly as a minor god or anything of that sort - but as a major cosmological antagonist for the very creme de la creme of the pantheon.

Read on to familiarize yourself with Enlil’s evil uncle.

Enmesharra’s name is relatively straightforward, and suitably grandiose for this sort of cosmological entity: he was the “lord of all me,” me being a difficult to translate term which can be more or less understood as “divine powers” or “ordinances.” Myths frequently describe gods receiving (from parents or unrelated high ranking deities), distributing (commonly Enki’s job), or even stealing (Inanna) the me.

However, “lord of all me” wasn’t exactly a part of this system. Rather, he was a vanquished lord of the cosmos who ruled it before the gods who were understood as its lords in everyday religion, chiefly Enlil. Frans Wiggermann went as far as proposing that Enmesharra represented the idea of inert, unchanging primordial cosmos, to be contrasted with the world actually known by the Mesopotamians, guided by Enlil’s dynamic and sometimes emotional rule.

Enmesharra’s rule evidently wasn’t understood as rightful. A text known as Enlil and Namzitarra appears to outright allude to usurpation: “When your uncle Enmesharra was a captive, after taking for himself the rank of Enlil, he said: ‘Now I shall know the fates, like a lord.’” Determining the fates was understood as the prerogative of Enlil and his wife Ninlil, representing the rule over the universe. A late ritual text additionally associates Enmesharra with the Anzu bird, known from a popular myth in which he too decides to steal Enlil’s power over the universe. A single myth about the confrontation between Enlil and his malign primordial relative doesn’t survive, but allusions in other texts seem to imply the confrontation took place in Shuruppak. It was also apparently believed that the defeated Enmesharra lived in the underworld, or even that he was a mere shade himself in the present as a result of being burned (during the confrontation, one would assume?).. Some texts simply indicate that he abdicated, but his antagonistic character is attested well enough to assume that wasn’t the default option. There are also references to various gods allied with Enlil having to guard Enmesharra for uncertain reasons.

Explaining the references to Enmesharra as Enlil’s uncle require a bit of context regarding genealogy of Mesopotamian gods: while popular reference works often simply state that Anu was Enlil’s father, in reality the situation was considerably more confusing and in sources such as god lists the default belief was that Enlil descended from a long line of so called “Enki-Ninki” gods (no relation to the wisdom god). All of his male ancestors in such lists, numbering between around half a dozen and 21 generations, bore names starting with the prefix en, much like Enlil himself and Enmesharra. The latter arose within the context of this tradition, and generally wasn’t associated with Anu. It has been proposed that this elaborate genealogy at least sometimes was understood as a way to avoid implications of divine incest. Anu was sometimes equipped with a similar, though less coherent, ancestor list of his own - a late adaptation of it, with some generations omitted and brand new ocs Apsu and Tiamat placed in a prominent position, is known from Enuma Elish.

While Enlil’s regular ancestors come in pairs and each En has a Nin as pair, Enmesharra usually appears alone, though Ninmesharra is known from at least some god lists. However, this name could also function as a title of Enlil’s wife Ninlil and especially of Inanna, neither of whom was associated with Enmesharra.

Regardless of whether a separate Ninmesharra was believed to exist or not, it was commonly agreed that Enmesharra did have children - there are frequent references to “seven (or more - as many as 15!) sons of Enmesharra” in various Mesopotamian sources. These are commonly identified with the Sebitti.

As a curiosity it’s worth noting that at least one more independent tradition about Enlil’s parentage existed, as an enigmatic figure separate from the Enkis and Ninkis, Lugaldukuga (“king of the holy mound”), is occasionally listed in theological works as his father. One text inexplicably equates Enmesharra and Lugaldukuga.

In the first millennium Enlil’s primacy started to decline, with imperial ideologies of Babylon and Assyria favoring Marduk and Ashur respectively. It didn’t help Enlil’s relevance that in the final centuries of Mesopotamian history in Uruk a new rather baffling theology redefined Anu as a more active ruler of the universe, at the expense of Enlil and Marduk, but also local superstars Ishtar and Nanaya and their courts (unlike the rise of Marduk it produced no interesting literary works, though. It was a rather crude development all around, in my opinion).

However, his malign uncle remained a denizen of the realm of mythical cosmology, and as a matter of fact some of the best preserved Enmesharra narratives no longer associate him with Enlil. The best example is the so-called “Enmesharra’s Defeat.” In this myth, his enemy is not Enlil, but instead Marduk, and Nergal makes an appearance as well as his jailer. Surviving fragments indicate that Enmesharra seemingly wanted to usurp Marduk’s rule (assisted by his seven sons), but curiously he’s also identified as a luminous deity, and after being vanquished his radiance is transferred to Shamash. Another text which alludes to animosity between Marduk and Enmesharra is the so-called “bird call text,” according to which a certain type of small bird is associated with the Cosmic Evil Uncle and its cry means “you have sinned against Tutu,” Tutu being a title of Marduk. He’s also a mainstay of various lists of defeated or conquered mythical evildoers, next to more famous today Tiamat, Asag and Qingu.

While no depiction of Enmesharra has been identified with certainty, two theories exist: Wilfred G. Lambert assumes that a mysterious cyclopic monster with a sun-like head known from at least one artifact might be him, while Frans Wiggermann instead proposes (in this article, generally irrelevant to discussion of Enmesharra) that scenes of judgment of an unidentified birdman on seals might represent his defeat. It’s also possible that some theomachy scenes represent myths of Enmesharra.

The mysterious birdman on a seal impression; source sadly unknown to me currently.

Further reading

Babylonian Creation Myths by W. G. Lambert

Mythological Foundations of Nature by F. A. M. Wiggermann

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Arahsamnum 2021: Nergal’s wives and children

While yesterday I’ve mentioned a little known (and largely speculative) instance of descent to the netherworld in Mesopotamian beliefs, the myth of Nergal and Ereshkigal, which also deals with the motif of katabasis, is one of the best known Mesopotamian tales (as well as one of the most commonly misinterpreted, but I think by now I wrote enough about that)/ However, it documents a relatively late development, and before Nergal was already regarded as king of the underworld - via assignment rather than marriage:

(translation by Gábor Zólyomi)

That doesn’t mean he was viewed as a bachelor, though. Under the cut you’ll find out everything there is to know about various traditions regarding Nergal’s marital status, and about at least one well attested child who can be attributed to him. As far as I can tell this is the most extensive summary of this sort in English.

Most major Mesopotamian gods, such as Nanna-Suen, Shamash or Adad were pretty consistently associated with the same spouses - in some cases the association was so strong that analogous gods from nearby areas had wives very clearly patterned after these of their Mesopotamian peers, for instance Ugaritic Yarikh and Hurrian Kushuh were both married to goddesses patterned after Ningal.

This can’t be said about Nergal: for some reason multiple conflicting traditions existed, many of them limited to specific locations. Due to space constraints and the nature of this series of articles, I won’t cover Ereshkigal here, and will instead focus on the options overlooked in discussion of Mesopotamian mythology (even though as far as I can tall most of them predate the myth of Nergal and Ereshkigal!).

Las: Nergal’s presumed oldest wife, attested as early as in the Ur III period in relation to Kutha, his main cult center, though her popularity only grew after the Old Babylonian period, after which she can be considered the “default” option. Her character is unknown and ill defined even by the standards of divine wives with no independent cult (as a side note, would anyone be interested in a longer post just about these? Would cover Aya, Shala, Ninlil, etc.). The etymology of her name is likewise a mystery.

The only solid information seems to come from the Weidner god list, which associates her with Bau, a healing goddess, and inexplicably calls her “the lady of Eridu,” a city located far away from Kutha and associated with Enka/Ea. Evidently pairing warrior gods with medicine goddesses was rather common (Ningirsu and Bau, Zababa and Bau, Pabilsag and Ninsina, Pabilsag and Ninkarrak…), so it wouldn’t be odd for Las to have such a role too, but no further detail is available and information in god lists can at times be the result of scribal wordplay or confusion and in cases such as Las, where there is hardly any other information to use for comparison, needs to be approached cautiously.

Curiously, as far as I can tell Nergal’s best attested daughter appears mostly in relation to her: documents from the Ur III period list them together at times. Also, in one case she appears with Nergal’s Elamite counterpart Simut.

Mami (or Mamitu): contrary to the name’s deceptive similarity to the word “mom” and its equivalents in many other languages, most likely NOT a mother goddess. It has been proposed that she was originally the spouse of Erra, “inherited” by Nergal when the two started to become hard to tell apart.

Curiously, while some god lists equate her with Las, in at least one ritual text - documenting deities of nearby cities (Kutha, Kish and Borsippa) “visiting” Marduk during the new year festival (long before he became famous) - Las and Mami appear side by side as distinct goddesses.

Not much can be said about her beyond that, though it’s worth noting one proposed etymology for her name is something like “frosty,” on the account of its similarity to the Akkadian word (note that Erra’s name means something like “scorching”). Also, she is Nergal’s wife both in sources from Nippur, whose main gods Enlil and Ninlil were regarded as Nergal’s parents (Las appears in a single god list from Nippur but not in the proximity of Nergal), and in the relatively late Epic of Erra.

She is not to be confused with another goddess with a homophonous name, Mami/Mama who seemingly was Ninhursag-like in character (though some researchers do seem to assume these two were one and the same), or with Mamu(d), the goddess of dreams, who was regarded as the daughter of Shamash and Aya, and as the wife of Shamash’s sukkal Bunene.

Admu: exclusive to Mari, a city in modern Syria close to the border of Iraq. It has been proposed that her name is derived from Adamma, a goddess who in nearby Ebla was the wife of Nergal’s counterpart Resheph in the 3rd millennium BCE. However it should be noted that by the time Admu is attested alongside Nergal, Adamma and Resheph were no longer associated with each other - after both of these Eblaite deities were adopted into Hurrian religion, Adamma formed a dyad with Kubaba (no relation to the similarly named Sumerian queen or to Cybele), while Resheph became Irsappa, the Hurrian god of the market. Elsewhere he retained his original character as a Nergal-like war and plague god, but to my knowledge not the association with Adamma.

Ninshubur: in 3rd millennium BCE Girsu Ninshubur was, for reasons which continue to be incomprehensible to me, regarded as the wife of Nergal. The tradition only had local relevance but for what it’s worth Ninshubur later reappears here and there as Nergal’s sukkal in place of the usual Ugur or Ishum, and two relatively late texts explain the name in the following terms: Nin-Shubur = Bel Erseti, eg. “Ninshubur = lord of the underworld.” Presumably this is an offshoot of such a tradition as nowhere else is the term Subur equated with erseti, and Ninshubur on her own demonstrably was not a chthonic deity.

Tadmushtum (or Dadmushtum): the only deity who can be with absolute certainty regarded as Nergal’s offspring. Her title - “daughter of E-Meslam” (E-Meslam being Nergal’s main temple) - leaves little room for speculation. It was shared with a certain Belet-Ili, though as she doesn’t appear in similar contexts as Tadmushtum and was normally a title of major goddesses I am unable to tell what does that mean in her case.

Tadmushtum was apparently a minor underworld goddess, and in offering lists accompanied her parents Nergal and Las.

Her name is assumed to have origin in a Semitic language, rather than in Sumerian, with possible etymologies including a derivation from words meaning “to humiliate oneself,” “to cover/hide something” or “destroy.” It has been proposed that a connection exists between her and T/Dadmish (ddmš in the alphabetic texts), a little known Ugaritic goddess.

Shubula: to my knowledge the only god to ever be possibly regarded as Nergal’s son. Or son in law maybe. His name seems to be derived from the Akkadian word abalu, “to be dry.” While Frans Wiggermann concluded in the late 1990s that he’s most likely meant to be Nergal’s son in the god list An-Anum, the matter is now regarded as less clear and it’s possible he was the son of Nergal’s sukkal Ishum instead. What is however certain is that he, as expected, was a chthonic deity. Also, the same god list states that he and Tadmushtum are a couple.

Shuwala: technically I’m not sure if she should be here. Shuwala was a goddess of uncertain origin attested alongside Nergal in Emar and in an Aramean inscription from the 1st millennium BCE. All that can be said about her with certainty is that she was associated with Mardaman, a city in northern Syria, and that she was seemingly an underworld goddess.

While by looking up her name online you can easily find a paper asserting she was analogous to Allani, it relies on extremely dubious scholarship and a fundamental misunderstanding of Hurrian divine names, as the author asserts that Shuwala is the “real” name of Allani - but Allani IS her name, most major native Hurrian gods had simple-epithet like names, as you may remember from an earlier installment of this series: Shaushka (“The Great”), Tashmishu (possibly “The Strong”), Nabarbi (“She of Nawar'' or perhaps “She of the pasture”), and so on. On top of that, Shuwala appears alongside Allani in a ritual; and while Allani was usually paired with Ishara, as I already discussed in their entries, Shuwala’s dyad bff was the aforementioned Nabarbi.

Further reading

Goddesses in Context: On Divine Powers, Roles, Relationships and Gender in Mesopotamian Textual and Visual Sources by J. M. Asher-Greve and J. G. Westenholz

Mamma, Mammi, Mammītum (Reallexikon der Assyriologie entry) by M. Krebernik

Tadmuštum (Reallexikon der Assyriologie entry) by M. Krebernik

Laṣ (Reallexikon der Assyriologie entry) by W. G. Lambert

Šubula (Reallexikon der Assyriologie entry) by P. Michalowski

God lists from Old Babylonian Nippur in the University Museum, Philadelphia by J. Peterson

Religions of Second Millennium Anatolia by P. Taracha

Šuwala (Reallexikon der Assyriologie entry) by M. C. Trémouille

Nergal A. Philologisch (Reallexikon der Assyriologie entry) by F. A. M. Wiggermann

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Arahsamnum 2021: Ishara

Ishara (middle) in the Yazilikaya sanctuary (wikimedia commons)

Few picks would be more appropriate to start the series on a high note than Ishara, one of my personal favorites. I covered her very briefly in a past post, but a slightly more detailed treatment is long overdue.

Ishara was many things to many people in many time periods, a woman of many talents, so to speak. What is of particular relevance for this post is that in Hurrian culture, she acquired an association with the underworld, and with so-called “former gods” residing there - essentially divine ancestors, some of them borrowed from Mesopotamiansources, some completely original. She also became a goddess of infectious diseases, and was said to be capable of inflicting a mysterious “Ishara disease” upon those who broke oaths sworn in her name.

In this context she also came to be associated with the Hurrian goddess of the dead, Allani (“The Lady”; rather popular and reasonably nice in the only myth she appears in, contrary to what her function might make you expect). A phenomenon common in Hurrian religion were dyads of goddesses with seemingly overlapping functions, and these two are one of the best attested examples. Both appear in a sadly very poorly preserved myth, but they share the same epithet (siduri, “young woman”) and in a so-called Hissuwa festival they were presented with matching outfits (Ishara with a red one, Allani with blue).

While Ishara is best attested as a Hurrian goddess, she had her origin in Ebla (modern Tell Mardikh), a 3rd millennium city in Syria with a rather unique culture, where she was connected to kingship. Much like the names of many other Eblaite deities, hers remains unexplained and likely comes from an unrecorded language. She was introduced from Ebla and nearby Mari to Mesopotamia, where she acquired an association with Ishtar, and by extension of it herself became a love goddess (bēlet ru'āmi, “lady of love,” a title shared with Ishtar and Nanaya), associated both with its physical aspect and with the institution of marriage. Her symbols were the bashmu, a type of mythical snake, and scorpions, a common symbol of marriage. As a love goddess she was also associated with cannabis.

Ishara was somewhat of a metaphorical divine social butterfly, acquiring associations with many other deities, not just Ishtar/Inanna and Allani. She is attested as a daughter of Enlil; in Nippur she shared a temple with Dagan, presumably due to both deities being perceived as masters of the western lands (not as spouses, though, unlike what early authors expected); in curse formulas she accompanies Ninkarrak, a medicine goddess; and in the famous treaty of Naram-Sin with Elam she’s one of the few non-Elamite deities invoked as witnesses. Sadly, despite all that ancient relevance she is obscure today, and even some researchers incorrectly gloss her as an “Ishtar byform.”

Further reading:

Translation of Gods: Kumarpi, Enlil, Dagan/NISABA, Ḫalki by A. Archi

The West Hurrian Pantheon and Its Background by A. Archi

A Royal Seal from Ebla (17th cent. B.C.) with Hittite Hieroglyphic Symbols by A. Archi

Goddesses in Context: On Divine Powers, Roles, Relationships and Gender

in Mesopotamian Textual and Visual Sources by J. Asher-Greve and J. G. Westenholz

Song of Release (translation) by Mary R. Bachvarova

Goddess Išhara by L. Murat

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Arahsamnum 2021: Sebitti

Yesterday’s entry already touched upon the topic of gods worshiped in Mesopotamia who had their origin further east. One group sometimes assumed to belong to this category were the Sebitti, the not particularly creatively named (lit. “the seven”) group of seven warrior deities.

Their role in religion differed slightly between Assyria and Babylonia: in the former they were part of the official state pantheon, invoked in treaties, depicted in symbolic forms on war chariots and believed to accompany rulers on military campaigns; in the latter area, however, they were largely limited to apotropaic functions, a role hardly different from that assigned to various fabulous beasts such as mushussu or lahmu. In both cases, though, they were imagined as about the same in appearance: anthropomorphic and armed with bows and hatchets.

In the Epic of Erra, Sebitti serve as the weapons of the eponymous god and urge him to seek new conquests instead of lazing around. Their role in this narrative is regarded as firmly negative, and arguably can be easily contrasted with that played by the protagonist’s sukkal Ishum, whose presence seems to have a calming effect (a pretty common function for sukkals - compare with features of Ninshubur I’ve highlighted many times in past posts, or with the role Nuska plays in the myth Enlil and Sud).

Their origin varies between texts: sometimes they were sons of Enmesharra, a vanquished ruler of the gods (remember this name, I’ll get back to him in a few days!); sometimes personified Pleiades or atmospheric phenomena; sometimes sons of Anu; sometimes subjects of Nergal or the closely related pair Lugalirra and Meslamtaea; and sometimes gods of foreign lands, such as Gutium or especially Elam. These versions could be combined in specific texts, for instance an apotropaic ritual invoking Sebitti to protect a house combines the Elamite and Enmesharra-related versions.

Some researchers seem to lean towards the possibility that the Elamite version was the original. Javier Alvarez-Mon in particular mustered a lot of evidence in support of the thesis that Sebitti were at the very least known in Elam, and that perhaps the image of seven bow-armed warriors was based on the descriptions of Elamite troops, renowned for their use of a unique type of bow.

Further possible hint about the nature of the Sebitti is the fact that while Nergal was the major god most frequently associated with them, a deity who had a special connection to them was also Narunde, in origin an Elamite goddess from Susa of unknown character. In Mesopotamia she was firmly regarded as a sister of the Sebitti, and often accompanied them in ritual texts. She evidently enjoyed some degree of popularity, as a personal name invoking her is known from Nippur.

In addition to the Sebitti, multiple other groups of seven lesser deities or demons are attested in Mesopotamian literature, for example “seven warriors” representing creatures conquered by Ninurta (unlike the Sebitti not necessarily anthropomorphic), “seven torches of battle” who were benevolent servants of Inanna, seven evil spirits of the underworld, seven birth goddesses partaking in the creation of mankind, and more.

Further reading:

Like a Thunderstorm: Storm-Gods ‘Sibitti’ Warriors from Highland Elam by J. Alvarez-Mon

Siebengötter A. Mesopotamien (Reallexikon der Assyriologie entry) by F. A. M. Wiggermann

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Arahsamnum 2021: Simut

As I said yesterday, associations between gods and celestial bodies in Mesopotamian literature were often much less direct than one would expect. Simut is yet another good example.

I need to preface the actual entry with an important clarification about Simut: contrary to early assumptions in scholarship, he was not an underworld god in his own right. He was associated with Nergal, yes, but this was rooted in shared character as warrior gods and association with the same celestial body rather than on full overlap of functions.

In Mesopotamian sources, Simut pretty much outright -was- Mars - his name can be found with either the divine determinative (DINGIR) or the astral one denoting a celestial body (MUL) prefacing it. Where did he come from, though, and what was he like? Read on to find out.

In origin, Simut was an Elamite god, much like already discussed Inshushinak. The meaning of his name to my knowledge isn’t known, but evidently it’s not a borrowing from Sumerian or Akkadian. His epithets give us a pretty good idea of how the Elamites perceived him: he was known as “the god of Elam,” “herald of the gods” and “mighty one, herald of the gods.” According to Wouter Henkelman, some caution is advised as “herald” is not necessarily the optimal translation of the Elamite term used in these titles, and it might designate some other type of official, perhaps military in nature.

While Nergal and Simut shared an association with Mars, they weren’t the only gods to be associated with it - for example, one myth appears to compare the medicine goddess Nintinugga and the prison goddess Manungal to Mars, perhaps to indicate their ability to navigate the underworld. In Simut’s case there is no indication that his astral aspect meant a link the underworld, though, and not all attestations of the corresponding planet in Mesopotamian texts are underworld-related - for instance, it could also be an omen of war, or simply “the Elam star” or “the strange star.”

Simut wasn’t the only elamite god to make a career in foreign lands as a personification of an astral body - Pinikir, the “Elamite Ishtar,” seemingly was perceived as a distinct goddess embodying the planet Venus by the Hurrians, and she appears in such a role in at least one copy of the Weidner god list. She is generally outside the scope of not only this article but the entire series, but I nonetheless recommend this article by Gary Beckman about her.

In many Elamite sources Simut seems to be associated with the imported Akkadian goddess Manzat, the rainbow. It’s commonly assumed they were spouses, though there seems to be no direct statement on the matter in any sources I’m aware of other than multiple shared temples, and such a belief was likely limited to Elam as in Mesopotamian sources Manzat is either unmarried (god list An-Anum) or the wife of the judge god Ishtaran. For some scholarly discussion of Manzat see this article by W. G. Lambert, you may also remember that I covered her in detail a few months ago.

Simut’s popularity was remarkable in his homeland: he appears frequently in personal names in all periods of Elamite history, and even in some Mesopotamian ones, perhaps due to the Elamite influence evident in sources from the early 2nd millennium BCE. He even gets a handful of mentions in early Persian sources.

It’s worth noting that while early 20th century authors such as Walther Hinz (avoid his publications; for decades they were the only in depth works on Elam but this is thankfully changing) found it preposterous that Persians had anything but disdain for Elamites (see the “further reading” section for details), the primary sources from the reign of earliest Persian emperors paint a very different image. Elamites, the indigenious population of the area which came to be known as Persia, while somewhat small in number, are attested in various strata of society, and even formed a part of the official administration - possibly in part repurposing preexisting Elamite structures.

Meanwhile, Elamite gods, especially the kingship god Humban, retained some degree of popularity at least for the first few decades. In the so-called Persepolis fortification archive there are mentions of both priests with Persian names in texts documenting festivals of Elamite gods and vice versa. Of course, the traces of Elamite culture eventually vanished, and it’s hard to imagine that later more dogmatic Zoroastrianism would have room for Inshushinak, Humban or Pinikir, but at least very early on it was possible for Ahura Mazda to coexist with them.

Further reading:

Humban and Auramazdā: royal gods in a Persian landscape by W. F. M. Henkelman

Šimut (Reallexikon der Assyriologie entry) by W. F. M. Henkelman

The Other Gods Who Are by W. F. M. Henkelman

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Arahsamnum 2021: Shulpae

Much like yesterday’s entry, today’s focuses on a figure whose (vague as it is) association with the underworld might come as a surprise, namely the little known god Shulpae. His name - “young one, shining forth” - might seem unusual for a god seemingly commonly associated with the underworld.

He belongs to the category of somewhat nebulous spouses of major deities - to be specific, he was the husband of Ninhursag in at least some locations, including the religiously prestigious Nippur. The phenomenon of ill defined divine spouses, with no well defined traits and no genealogy, both wives (Laz, Sarpanit, Tashmetu, etc.) and husbands (Haya or today’s “protagonist”) is reasonably common in Mesopotamian mythology, but to my knowledge has hardly been documented in detail.

I suppose the mention of a spouse of Ninhursag who’s evidently not Enki might come as a surprise, so two things require an explanation. Myths didn’t necessarily form a coherent whole, and local traditions could be contradictory. There were divine couples which seem basically inseparable regardless of location - Shamash and Aya or Nanna-Suen and Ningal being probably the best examples - but even major deities could have different spouses in different locations or time periods.

Additionally, while due to outdated 19th century views Ninhursag is treated as some reflection of a “primordial mother goddess” and other such laughably ahistorical things, it’s probably more accurate to say that Ninhursag as depicted in some myths and in late god lists was an amalgamation of various deities with not necessarily identical associations and spheres influence who arose due to politically motivated conflation. Iconographic evidence appears to indicate, for example, that Ninhursag and Ninmah were initially completely different deities, one associated with wild animals and the other with domestic; meanwhile Aruru was seemingly initially a vegetation goddess associated with Nisaba rather than an epithet of Ninhursag.

The view that Shulpaewas Ninhursag’s husband seems to be firmly associated with the view that she was Enlil’s sister, as he was sometimes called “brother in law of Enlil.” Of course, as expected, much like many other lesser relatives he was regarded as Enlil’s coutier - specifically as his “lord of the banquet table.”

No known sources appear to provide him with a genealogy - this isn’t uncommon for divine spouses who weren’t major deities in their own right. Other examples include Shamash’s wife, the dawn goddess Aya; Adad’s wife in Mesopotamia, rain goddess Shala; Nisaba’s husband, storehouse(?) god Haya; Nergal’s multiple nebulous regional wives (more on them in a few days); even Ea’s wife Damkina (firmly associated with Ninhursag and/or Ninmah) receives no genealogy in the Enuma Elish. I initially thought it might just mean that the wife’s family wasn’t regarded as particularly important, but there are evidently nebulous husbands too, and in the myth Enlil and Sud the parentage of his wife is a pretty big deal, and was evidently relevant in cult too, so I’m no longer sure if it’s just that.

Wilfred G. Lambert isuggested that certain aspects of divine genealogy, like equipping major gods with insanely long lists of ancestors, was a development meant to reflect disdain for incestuous motifs in mythology - while he doesn’t extend the argument to spouses with no set origin, perhaps the logic was similar? It’s also possible some of them simply developed long before divine genealogies became standardized to a degree and never received them afterwards, of course.

Most of what we know about Shulpae’s character boils down to the nature of his epithets and the contents of a single hymn. They point at an association with wild animals and vegetation, but also with the astral sphere and with diseases. However, he is also referred to as a “roving namtar demon,” and in medical texts some diseases are said to be caused by the “hand of Shulpae,” a common figure of speech assuming specific afflictions to be the manifestation of divine wrath. “Hand of Ishara” in particular is a well attested example.

As an astral body Shulpae was associated with Jupiter - yet another sign that you need to be extremely cautious about online claims about exclusive associations between Mesopotamian deities and astral bodies. More such evidence will be discussed tomorrow - stay tuned!

Further reading:

Goddesses in Context: On Divine Powers, Roles, Relationships and Gender in Mesopotamian Textual and Visual Sources by J. M. Asher-Greve and J. G. Westenholz

Šulpaʾe (Reallexikon der Assyriologie entry) by P. Delnero

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Arahsamnum 2021: Nungal

Yesterday’s post covered nebulous deities who, by the virtue of being at various points in time and space regarded as Nergal’s wives Today’s topic is instead a goddess who, while also known as a daughter in law of Enlil and Ninlil, is decidedly less nebulous than her husband. Nungal (also known as Manungal) was the goddess of prisons, and her husband was the obscure god Birdum. How obscure? It will suffice to say -I- was unable to find out much of value about his nature.

Nungal was chiefly associated with Nippur, though Wilfred G. Lambert considered it possible that she was originally the tutelary goddess of some forgotten town who simply outlived her original cult center as part of the pantheon of a major city.

An alternate form of her name was Manungal, possibly a shortened form of Ama-Nungal, “Mother Nungal.” In some contexts it was treated as if it were an Akkadian equivalent of her name, even though both words are Sumerian. Due to their names being rather similar she was also sometimes confused with Ninegal, the goddess of palaces (not to be confused with Inanna’s epithet with the same meaning). You may remember her from a brief mention in the Lagamar post from a few days ago. To my knowledge, unlike Ninegal, Nungal doesn’t appear anywhere as Lagamar’s mom, though.

Our main source of information about her is the hymn to Nungal - she is actually extremely uncommon in texts otherwise, which makes it all the more unusual that such a long and detailed composition was dedicated to her. Nungal’s character is pretty well defined in it: she is the “neck-stock of the Anunna gods,” punishes the wicked but shows compassion to the righteous. The hymn also introduces a host of servant deities associated with her.

As an extension of her functions, Nungal was also regarded as an underworld goddess. In god lists she usually appears in sections dedicated to such deities (puzzlingly sometimes alongside the beer goddess Ninkasi), and in a surviving mythical fragment she appears in the underworld alongside fellow courtier of Enlil, Nintinugga. There is even an incantation which calls her the “lady of the underworld,” nin-kurra. The same incantation indicates she was believed to be the bane of Namtar.

There are a few references to Ereshkigal being her mother, though to my knowledge the father goes unstated, similar to the instances where Ninazu is her son (the only instance I can think of where a deity is referred to as Ereshkiga’s child and the father is listed is an unusual text presenting the otherwise unknown view that Namtar was the son of Ereshkigal and Enlil, a strange and otherwise unattested pairing). In one case Ereshkigal is even credited with bestowing Manungal’s roles upon her. Of course, this tradition wasn’t universally accepted, since for instance in the well known myth of Nergal and Ereshkigal she’s evidently unmarried and has no children.

Further reading:

Nungal (Reallexikon der Assyriologie entry) by A. Cavigneaux and M. Krebernik

The Theology of Death by W. G. Lambert

Two New Sumerian Texts Involving The Netherworld and Funerary Offerings by J. Peterson

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Arahsamnum 2021: Belet Shuhnir and Belet Terraban

Last few days focused on the matter of foreign deities in Mesopotamia. I also touched upon this topic before, in the entries covering Ishara, Inshushinak and Allani.

As I noted before, some of the foreign deities known from archives of the Third Dynasty of Ur are well known and correspond to major cities in nearby areas - Belet Nagar, Shaushka or Ishara might not captivate modern imagination the way Greek or Scandinavian deities do, but they are well known to experts and associated with cities which have been excavated and meticulously documented. This can’t be said about the duo introduced in today’s installment.

Belet Shuhnir (”Lady of Shuhnir”) and Belet Terraban (”Lady of Terraban”) are almost inseparable, pretty much always occurring as a pair - I was only able to track down two exceptions: Puzur-Inshushinak’s inscription from Susa mentions Belet Terraban on her own, and an inscription of an Amorite chieftain invoking only Belet Shuhnir.

There is relatively little information about their character, though as noted by Tonia Sharlach it has been summed up as “lugubrious” in scholarship based on the names of celebrations dedicated to them: "wailing ceremony," "the festival of chains" and "place of disappearance." It has been proposed that their names indicate they were understood as periodically descending to the underworld, or captive in some other way. For the time being, they sadly remain blank slates otherwise.

It’s worth noting that on seals they were seemingly associated with Tishpak, the main god of Eshnunna, who was so foreign experts up to this day can’t figure out his origin, with even the greatest authorities in the field only arriving to imprecise conclusions such as “sounds Elamite” or “perhaps an Elamite rendering of Hurrian Teshub would sound similar.”

The areas designated as “Shuhnir” and “Terraban'' were most likely located somewhere in the north of the Diyala region of modern Iraq, perhaps roughly in the Kirkuk area, and as such were outside the sphere of influence of major Mesopotamian polities of the late 3rd and early 2nd millennium BCE. This is somewhat of a recurring pattern when it comes to new deities appearing for the first time in this period in Mesopotamia - Allani and Shaushka were imported from predominantly Hurrian areas; Dagan and Ishara, while already known before, grew in prominence as “representatives” of Syrian states, and were joined by Dagan’s wife Shalash, Haburitum personifying the Khabur river, Belet Nagar (from the eponymous city), and Suwala fro Mardaman.

Notably absent seem any gods from the east, though it is known that Ur III kings at the very least supported the temples of Inshushinak and Ruhurater in conquered territories, and Gary Beckman suspects Pinikir had some presence in Mesopotamia in this period. There are also deities of uncertain origin who likewise appear for the first time in lists from the Ur III period, for instance Nanaya or Tadmustum.

The rationale between the celebration of a high number of foreign and otherwise new deities in the Ur III court remains unknown. Many such areas from which they arrived weren’t under the control of Mesopotamian kings; simultaneously areas with whose kings they were allied seem absent, notably no gods who can be plausibly assumed to have their origin in Marhashi far to the east are anywhere to be found. It has been proposed that some of them were introduced by royal wives from faraway areas, though evidence supporting this theory is inconclusive.

Further reading:

Puzur-Inšušinak, the last king of Akkad? Text and Image Reconsidered by J. Alvarez-Mon

NIN-Šuḫnir und NIN-Terraban (Reallexikon der Assyriologie entry) by A. Cavigneaux and M. Krebernik

Comments on the Translatability of Divinity: Cultic and Theological Responses to the Presence of the Other in the Ancient near East by B. Pongratz-Leisten

Foreign Influences on the Religion of the Ur III Court by T. Sharlach

Local and Imported Religion at Ur Late in the Reign of Shulgi by T. Sharlach

Shulgi-simti and the Representation of Women in Historical Sources by T. Sharlach

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Arahsamnum 2021: Nintinugga

As you might remember from my past posts, I lamented the complete irrelevance of Mesopotamian medicine goddesses in modern perception; even in scholarship they aren’t all that prominent, which is rather odd considering they rank only behind Inanna et al. and the most popular divine wives (especially Shamash’s wife Aya) in popularity through most of mesopotamian history as far as the most prominent deities go, not to mention their prominence in nearby Syrian cities like Terqa and Mari. I felt it’s therefore mandatory to include one in my current article series.

While it is plausible that conflation of Ninisina and Ninkarrak did occur every now and then, and Gula is outright sometimes assumed to be an epithet which became the default name more than a distinct deity, Nintinugga is basically almost always kept apart from them in known sources, and has her own unique niche - her cult was centered in Nippur, and god lists present her as Enlil’s and Ninlil’s courtier. She also had a few unique titles, such as Belet Balati, “mistress of life.”

One text apparently mentions her visiting Ninisina, which confirms the two were understood as distinct despite overlapping functions - compare to Inanna and Nanaya or Ishara, or to use a Greek example instead, to Apollo and Helios.

What’s of particular relevance to us today, though, is her underworld association. Her name arguably foreshadows it - one can safely expect “mistress who revives the dead” to show an interest in death and what comes next. Her common epithet, Nintillaugga, had similar connotations: “lady of life and death.”

This took two forms. In the cultic sphere, Nintinugga likely had a role in funerary libations, as she is described providing the dead with clean water, a role also ascribed to Nergal elsewhere; it’s also possible she shared the association with the planet Mars or, as the Mesopotamians called it, “the Elam star,” which might represent a belief that she was capable of navigating through the underworld. In myths she was associated with Ereshkigal. with one notable - sadly fragmentary text - details her visit in the underworld alongside the prison goddess Manungal (who is generally speaking extremely rarely attested in known texts). There is also some evidence that the underworld god Ninazu was viewed as her father, and that she was regarded as an enemy of the disease demon asag.

Further reading

Goddesses in Context: On Divine Powers, Roles, Relationships and Gender in Mesopotamian Textual and Visual Sources by J. M. Asher-Greve and J. G. Westenholz

Ancient Mesopotamian Religion: A Profile of the Healing Goddess by B. Böck

Two New Sumerian Texts Involving The Netherworld and Funerary Offerings by J. Peterson

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Arahsamnum 2021: Ninkilim

Yesterday I mentioned Ninkilim (alongside Pazuzu) in order to try to figure out the meaning of Kanisurra’s obscure epithet. Today, I will focus on him alone.

Ninkilim was very likely in origin the deification of the mongoose. He was also known as “lord of teeming creatures” in Sumerian and “lord of wild beasts.” in Akkadian. However, make sure not to confuse Ninkilim with the incantation goddess, Ningirima - you might find claims they were analogous in old reference works and on wikipedia, but newer research casts such claims in doubt. All they definitely had in common was one cult center, the town Mur(um).

The main source of available information about this deity is the incantation series Zu-buru-dabedda, “to paralyze the locust��s tooth,” which formed a part of the so-called “exorcist manual” known from many major Mesopotamian cities of the 1st millennium BCE, though very likely based on material which was already in circulation for a long time back then.

Creatures under Ninkilim’s control included locusts, caterpillars, various grubs and small rodents. Collectively they were known as “the dogs of Ninkilim.” How come? Poetic descriptions of locusts in Mesopotamian literature might offer a clue: it seems that their voracious nature was metaphorically described as possessing dog teeth, probably due to perception of dogs as constantly scavenging for food. Metaphorical references to animals or mythical beings as “hounds” of a specific deity can be found in other contexts too, though.

While Ninkilim himself has no direct underworld connection, a few rituals appear to indicate the underworld was regarded as the place where his “dogs” were expected to head after a successful exorcism.

Curiously, despite being a low ranking deity Ninkilim was nonetheless believed to possess a sukkal (servant deity), namely Ushumgal. This name was normally assigned to a type of monster. The meaning is pretty straightforward, “great venomous snake.” While I haven’t seen any discussion of this topic in what few articles have been written about Ninkilim, it certainly feels tempting to connect it to the mundane mongoose’s well known resistance to snake venom.

As in the case of many other minor deities, Ninkilim’s gender varies between sources. According to Andrew George, who translated most of the known incantations against field pests, Ninkilim seems to be female in the god list An-Anum, but other sources - namely the incantations themselves - regard him as a male deity.

Further reading:

The Dogs of Ninkilim: Magic against Field Pests in Ancient Mesopotamia by A. R. George

The Dogs of Ninkilim, part two: Babylonian rituals to counter field pests by A. R. George and J. Taniguchi

Mungo (Reallexikon der Assyriologie entry) by W. Heimpel

Nin-girima I. Beschwörungsgöttin (Reallexikon der Assyriologie entry) by M. Krebernik

Ušumgal (Reallexikon der Assyriologie entry) by M. Krebernik

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Arahsamnum 2021: Kanisurra

Yesterday’s post dealt in a small capacity with the concept of entrance to the underworld, today’s focuses on a minor goddess who possibly originally personified this location in Mesopotamian beliefs, Kanisurra. Most of the time you’re going to see her brought up in the context of her role as a courtier, or later on daughter, of Nanaya, but her origin appears to be considerably weirder. I must admit that I had to do a double take if I’m really reading a reputable source when I first stumbled upon her, as her combination of proposed functions made her seem like a contemporary original character rather than an ancient deity of limited significance.

The proposed etymology of her name, based on alternate forms attested in various texts, is that it was derived from ganzer, a Sumerian term denoting either the entrance of the underworld, or the underworld as a whole. It has therefore been proposed that she was an underworld deity, However, there is little evidence for it other than etymology alone (though there are multiple plausible transitional forms of the name in documents from the Ur III period, namely Gansura and Ganisurra) - she appears in a single mourning ritual, but it is uncertain if it’s any indication of her character or if it simply had something to do with its location, Uruk, where she had a temple.

Other documents do not provide clear evidence of Kanisurra’s character either. The association with Nanaya, Ishara and co. might point to a love-related function, and as a matter of fact she does appear in texts dealing with relevant matters.. However, incantations also give her the unique title bēlet kaššāpāti - “lady of sorceresses.” As the best known passage using it implores her (as well as Ishtar, Dumuzi and Nanaya) to counter the influence of malign sorcery, I think it’s safe to say she was their “lady” in the same way Pazuzu presided over demons, or Ninkilim over field pests - eg. that their presence was meant to keep their unruly “subjects” in check.

Her most consistent trait was the association with love goddess and Inanna bootleg par excellence, Nanaya (note that contrary to what many online sources say Nanaya was a separate goddess from Inanna/Ishtar). While initially it was likely simply based on shared association with Uruk, and transfer of their cults to the same locations during the city’s temporary decline, in late theology she was viewed as Nanaya’s daughter.

Sadly, not much more can be said about Kanisurra, unless you’re interested in investigating administrative documents detailing the offerings made to her in Uruk.

Further reading:

The Pantheon of Uruk During the Neo-Babylonian Period by P. A. Bealieu

Kanisurra (Reallexikon der Assyriologie entry) by D. O. Edzard

Evil Helpers: Instrumentalizing Agents of Evil in Anti-witchcraft Rituals by D. Schwemer

Warum sitzt der Skorpion unter dem Bett? Überlegungen zur Deutung eines altorientalischen Fruchtbarkeitssymbols by A. E. Zernecke

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Arahsamnum 2021: Inshushinak

A figurine from Susa tentatively identified as Inshushinak in a currently inaccessible article on the Louvre’s site

As the two preceding entries dealt with Lagamar and Ishme-karab, it only feels appropriate to cover Inshushinak in today’s installment.

Inshushinak’s name is pretty self explanatory - it’s derived from Sumerian and means roughly “lord of Susa,” which is exactly what he was famous for: Susa was a prominent city on the border of Mesopotamian and Elamite spheres of influence, and Inshushinak was its tutelary god. No depictions of him have been identified with certainty, though it has been suggested that the so-called “god on snake throne” motif common in Elamite religious art in at least some contexts represents Inshushinak.

In Mesopotamia proper he was of little importance, though it’s evident he was known very early already (unlike many other foreign deities, who only start to appear in Mesopotamian records in the Ur III period). In god lists he usually appears close to various snake-themed oddities like Tishpak and Ishtaran, and every now and then one king or another would visit his temple in Susa. However, next door in Elam he was one of the most prominent gods.

While Susa was his holy city, his prevalence in personal names indicates that he was held in high esteem by Elamite rulers regardless of origin through much of said cultural area’s history. Some of the most famous Elamite rulers, such as Puzur-Inshushinak, were named in his honor. While no texts providing detailed accounts of Elamite theology are currently known, it has been established that Inshushinak was regarded as rišar napappir, “greatest of gods.” Only other Elamite deity referred to with such an epithet was considerably less well known Humban. Inscriptions also indicate that to Elamite rulers, Inshushinak was a source of royal power, similar to Enlil or Inanna to their Sumerian counterparts, Dagan to those in the upper Euphrates area, and so on.

What makes Inshushinak rather unique as far as heads of pantheons go is the fact that it seems his primary character was that of an underworld judge. One of his temples in Susa was known simply as haštu, “tomb,” and the best preserved texts dealing with his role in the beliefs of inhabitants of Elam - at least those who lived in Susa itself - are funerary in character.

According to them, Inshushinak awaited the souls of the dead in the underworld; his assistants, Lagamar and Ishme-karab were responsible for guiding each deceased person to him, and it has been proposed that they took the roles of defendant or prosecutor - or rather advocatus dei and advocatus diaboli - during the procedure. For well over a century it has been the consensus that the judgment involved the weighing of souls, and that another participant was an unnamed deity responsible for it, but a recent translation of the source material by Nathan Wassermann challenges this notion, though confirms other assumptions about the character of Inshushinak and his underlings.

Inshushinak’s authority as a judge extended beyond the underworld, and he was invoked as a guardian of oaths and in various legal proceedings, a role which in Mesopotamia was usually assigned to the sun god Utu/Shamash or to the little known, though seemingly major, Ishtaran (no obvious relation to Ishtar). Due to shared connection to snakes, the underworld and law, and close location of their holy cities, a connection between Ishtaran and Inshushinak has been proposed by some researchers, with one source going as far as assuming god lists were meant to indicate they were viewed as brothers.

Further reading:

The Other Gods who are: Studies in Elamite-Iranian Acculturation Based on the Persepolis Fortification Texts by W. M. F. Henkelman

The Elamite Triads: Reflections on the Possible Continuities in Iranian Tradition by M. Jahangirfar

Tišpak (Reallexikon der Assyriologie entry) by M. Stol

Unterwelt, Unterweltsgottheiten B. In Susa (Reallexikon der Assyriologie entry) by J. Tavernier

The Susa Funerary Texts: A New Edition and Re-Evaluation and the Question of Psychostasia in Ancient Mesopotamia by N. Wassermann

Transtigridian Snake Gods by F. A. M. Wiggermann

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Arahsamnum 2021: Ishme-karab

Since yesterday’s post was about Lagamar, it is basically impossible not to follow up with one of his almost inseparable companion in sources from Susa. This name is similar descriptive and can be explained as “(he/she) heard the prayer.”

Ishmekarab’s gender is presently uncertain. While Wilfred G. Lambert wrote in what’s most likely the only article just about Ishme-Karab that the deity is almost definitely male, though accepted that on grammatical grounds it’s possible that’s not necessarily the case, while Florence Malbran-Labat regards them as a goddess. Nathan Wassermann recently described Lagamar and Ishmekarab as a couple but didn’t weigh in on the matter of either deity’s gender.

Technically speaking, Ishmekarab was less strictly an underworld deity and more a broadly law-related one. In Mesopotamia proper they are commonly listed as a member of groups of judge deities, for example so-called “standing gods of Ebabbar,” servants of Shamash from his temple in Larsa, or three different groups of Assyrian divine judges. In Susa, where they presumably were introduced in the Old Babylonian period, they appear alongside the local head god Inshushinak in oath formulas, and oath breakers were warned that they might end up smitten by the “mace of Ishmekarab.”

In the context of Susa funerary texts, Lagamar and Ishmekarab appear side by side as two gods who escort each dead person to judgment. Wouther Henkelman proposed that the former served as “advocatus diaboli” and the latter as “advocatus dei,” relying on the meaning of their names and other evidence.

Further reading:

The Other Gods who are: Studies in Elamite-Iranian Acculturation Based on the Persepolis Fortification Texts by W. M. F. Henkelman

The Elamite Triads: Reflections on the Possible Continuities in Iranian Tradition by M. Jahangirfar

Richtergott(heiten) (Reallexikon der Assyriologie entry) by M. Krebernik

Išme-karāb (Reallexikon der Assyriologie entry) by W. G. Lambert

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Arahsamnum 2021: Lagamar

While less famous in ancient times than Ishara (covered yesterday), and much less studied today, Lagamal shares with her the status of a cosmopolitan deity, with attestations coming from as far west as Mari and Terqa in Syria, and as far east as Susa in Elam (western part of modern Iran). His point of origin is assumed to be Dilbat, a city in northern Mesopotamia mostly known for the so-called “Dilbat hoard,” an exceptionally well preserved collection of ancient jewelry.

The city god of Dilbat, and also Lagamar’s father, was the farming god Urash, a “Ninurta type” deity. He was completely unrelated to the other Urash, a spouse of the sky god Anu. His wife was Ninegal aka Belet Ekallim, the goddess of palaces (and occasionally an epithet of other goddesses, chiefly Inanna and Manungal). In at least one case all 3 appear together as a family. In some sources Urash was also the father of Nanaya, a “bootleg Inanna” of sorts, but tragically no such a source features Lagamar as well.

With a name which quite literally means “no mercy” in Akkadian, Lagamal was, as expected, imagined as an underworld deity. This is best attested in sources from Susa, so called “Susa funerary texts,” which list him as one of the gods escorting the dead to the judgment of Inshushinak, the god of the underworld in local beliefs. However, it was evidently well known elsewhere too, as god lists tend to associate Lagamar with Nergal.

Infernal character didn’t stop people from naming children in his honor, though. and there are even attestations of a name which can be translated as “Lagamar is the one who spares,” Lagamar-gamil. Lagamar names could have been something like an expression of local patriotism, as many people bearing them attested from various Mesopotamian cities seemingly hailed from Dilbat.

Curiously, while Lagamar is definitely male in sources from Dilbat or related to Dilbat. and most likely in these from Susa, in Terqa the name was evidently regarded as belonging to a female deity. Little detail is available on the cult of Lagamar in Syria, but texts from Mari attest that her statue took part in some sort of pilgrimage (a custom also attested for other Syrian gods, for example Dagan and Belet Nagar).

Further reading

The Elamite Triads: Reflections on the Possible Continuities in Iranian Tradition by M. Jahangirfar

Lāgamāl (Reallexikon der Assyriologie entry) by W. G. Lambert

A Babylonian Official at Tilmen Höyuk in the Time of King Sumu-la-el of Babylonby G. Marchesi and N. Marchetti

The Susa Funerary Texts: A New Edition and Re-Evaluation and the Question of Psychostasia in Ancient Mesopotamia by N. Wassermann

11 notes

·

View notes