#Zoe Heaps Tennant

Text

At Ninety-One, Alanis Obomsawin Is Not Ready to Put Down Her Camera

She revolutionized cinema and is inspiring the next generation of Indigenous filmmakers

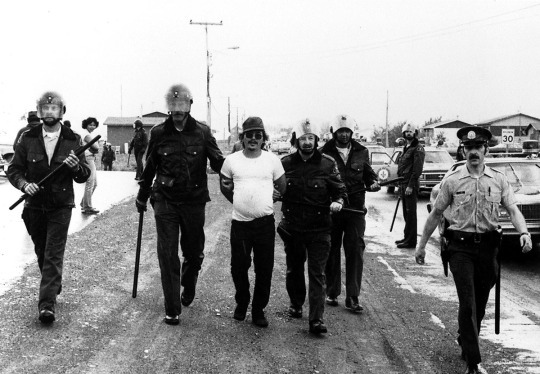

Until a few years ago, the National Film Board was headquartered in a sprawling suburban complex off a Montreal highway. In 2019, it moved into its new downtown space, a slick thirteen-storey building designed with Obomsawin in mind. In a reception room on the main floor, a recording of an interview with her plays on loop. On the second floor is the 138-seat Alanis Obomsawin Theatre. A few floors above, a still from Kanehsatake: 270 Years of Resistance covers the wall of a conference room. If her work and image are part of the building’s DNA, it’s because she has become, as Wente puts it, the raison d’être of Canada’s public film producer and distributor. “If you were to ask me why the NFB should exist,” Wente tells me, “she’s why. She’s who I would point to.”

Read more at thewalrus.ca.

Stills and photography from When All the Leaves Are Gone (2010), Kanehsatake: 270 Years of Resistance (1993), Christmas at Moose Factory (1971), and Incident at Restigouche (1984), courtesy of the National Film Board

#Film#Documentary#Indigenous#Alanis Obomsawin#Directed by women#Photography#September/October 2023#Zoe Heaps Tennant

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

At Ninety-One, Alanis Obomsawin Is Not Ready to Put Down Her Camera

She revolutionized cinema and is inspiring the next generation of Indigenous filmmakers

On a hot Wednesday morning in July 1990, Alanis Obomsawin was listening to the car radio on her way to work when she heard about shots fired in Kanehsatà:ke. Instead of continuing on to her office at the National Film Board of Canada in Montreal, she sped straight to the Kanien’kehá:ka (Mohawk) community, about an hour’s drive outside the city. Obomsawin, who is Abenaki, would later tell a reporter that she knew an Indigenous person had to be there to document what was happening.

Read more at thewalrus.ca.

Photography by Shelby Lisk (shelbyliskphoto.com)

#Film#Documentary#Indigenous#Alanis Obomsawin#National Film Board#Photography#September/October 2023#Zoe Heaps Tennant#Shelby Lisk

1 note

·

View note

Photo

The New Lobster Wars

Inside the decades-long East Coast battle between fishers and the federal government over Mi'kmaw treaty rights

A couple of years ago, after Indigenous fishing boats were vandalized, Sproul said, some leaders in the fishing community decided they’d had enough. Impatient with government inaction, Sproul, alongside other non-Indigenous fishing-industry representatives and Mi’kmaw chiefs, started a dialogue group to discuss fishing matters. The informal committee held a handful of meetings and calls about the fisheries, but as tensions escalated, the group unravelled. “Things are about to turn bad,” Sproul messaged me this past August. Shortly afterward, Sipekne’katik First Nation launched its moderate-livelihood fishery and conflicts started to flare.

Read more at thewalrus.ca.

Artwork by Marcus Gosse (marcusgosse.ca).

#Justice#Lobster#Indigenous#Mi'kmaq#Treaty rights#Moderate livelihood#January/February 2021#illustration#Marcus Gosse#Zoe Heaps Tennant

2 notes

·

View notes