#entertained or dismissed. this is a social space and we’re people and everybody just needs to recognize that. like. last week my introverted

Text

just an fyi, and it feels like it needs to be said here: your blog is your own space and you should be able to say whatever the fuck you want. if you’re sad? vent. get sad. maybe put it under a cut, definitely tag it, but get sad. if you feel like you need someone to talk to? drop a freaking message about how you’re feeling like you could use a buddy, or anything randomly engaging. if you’re having a hard time, you should feel safe and okay to talk about it in your own space. we’re writers and we’re people and while there’s a lot to be said for how engagement outside of oneself is necessary in rp (and really really needs to improve), i think there’s a lot that must be said about people reaching out to others. it’s become so solitary here — the whole ‘reblog from source’ thing when it comes to shit like about and musings is absurd. the whole refusing to like things is ridiculous. yes, curate your space, that’s important, but curating your space into a studio apartment only you live in doesn’t make this a community anymore, it makes it a studio apartment you live in.

just be yourself here. do whatever you want. but i’m always saying: remember you’re not alone, and don’t let yourself feel that way.

#ooc. o kaptain.#[this is illogically worded and after an argument I’m already upset but I just felt like this has to be put here. it’s been sitting on my#brain for so long and it’s something i just wanted to discuss. the way the rpc has become not even an echo chamber just… a shitty ny#apartment only one person lives in that can fit your fridge and your bedroom in the same room. the way literal fandoms have divided each#other through nothing but massive senses of entitlement and so much gatekeepy fucking language. it’s exhausting to watch this happen#literally all because i have no idea where interaction went and yes I’ve been virtually inactive for months now but. it absolutely isn’t for#lack of trying to come back. it’s hugely due to a lack of interaction whenever I reach out and then the feeling like I’m being either#entertained or dismissed. this is a social space and we’re people and everybody just needs to recognize that. like. last week my introverted#broski started discussing how as he’s older he feels loneliness more tangibly but he hates people and i looked right at him and said …yeah#dude. that’s natural. we’re humans. we need each other to live. we need spaces we create and communities we make. but like. there need to be#interactive people in those spaces. we’re social creatures. i love you guys and this is a ramble but… it’s been on my mind awhile. and#frankly? feels kinda good to finally speak my mind.]

37 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Bong Hit!

Today Parasite overtook The Godfather as the highest-rated narrative feature film on Letterboxd. We examine what this means, and bring you the story of the birth of the #BongHive.

It’s Bong Joon-ho’s world and we’re just basement-dwelling in it. While there is still (at time of publication) just one one-thousandth of a point separating them, Bong’s Palme d’Or-winning Parasite has overtaken Francis Ford Coppola’s Oscar-winning The Godfather to become our highest-rated narrative feature.

In May, we pegged Parasite at number one in our round-up of the top ten Cannes premieres. By September, when we met up with Director Bong on the TIFF red carpet, Parasite was not only the highest-rated film of 2019, but of the decade. (“I’m very happy with that!” he told us.)

Look, art isn’t a competition—and this may be short-lived—but it’s as good a time as any to take stock of why Bong’s wild tale of the Kim and Park families is hitting so hard with film lovers worldwide. To do so, we’ve waded through your Parasite reviews (warning: mild spoilers below; further spoilers if you click the review links). And further below, member Ella Kemp recalls the very beginnings of the #BongHive.

Bong Joon-ho on set with actors Choi Woo-shik and Cho Yeo-jeong.

The Letterboxd community on Parasite

On the filmmaking technique:

“Parasite is structured like a hill: the first act is an incredible trek upward toward the light, toward riches, toward reclaiming a sense of humanity as defined by financial stability and self-reliance. There is joy, there is quirk, there is enough air to breathe to allow for laughter and mischief.

“But every hill must go down, and Parasite is an incredibly balanced, plotted, and paced descent downward into darkness. The horror doesn’t rely on shock value, but rather is built upon a slow-burning dread that is rooted in the tainted soil of class, society, and duty… Bong Joon-ho dresses this disease up in beautiful sets and empathetic framing (the camera doesn’t gawk, but perceives invisible connections and overt inequalities)—only to unravel it with deft hands.” —Tay

“Bong’s use of landscape, architecture, and space is simply arresting.” —Taylor Baker

“There is a clear and forceful guiding purpose behind the camera, and it shows. The dialogue is incredibly smart and the entire ensemble is brilliant, but the most beautiful work is perhaps done through visual language. Every single frame tells you exactly what you need to know while pulling you in to look for more—the stunning production design behind the sleek, clinical nature of one home and the cramped, gritty nature of the other sets up a playpen of contrasts for the actors and the script.” —Kevin Yang

On how to classify Parasite:

“Masterfully constructed and thoroughly compelling genre piece (effortlessly transitioning between familial drama, heist movie, satirical farce, subterranean horror) about the perverse and mutating symbiotic relationship of increasingly unequal, transactional class relationships, and who can and can’t afford to be oblivious about the severe, violent material/psychic toll of capitalist accumulation.” —Josh Lewis

“This is an excellent argument for the inherent weakness of genre categories. Seriously, what genre is this movie? It’s all of them and none of them. It’s just Parasite.” —Nick Wibert

“The director refers to his furious and fiendishly well-crafted new film as a ‘family tragicomedy’, but the best thing about Parasite is that it gives us permission to stop trying to sort his movies into any sort of pre-existing taxonomy—with Parasite, Bong finally becomes a genre unto himself.” —David Ehrlich

On the duality of the plot:

“There are houses on hills, and houses underground. There is plenty of sun, but it isn't for everybody. There are people grateful to be slaves, and people unhappy to be served. There are systems that we are born into, and they create these lines that cannot be crossed. And we all dream of something better, but we’ve been living with these lines for so long that we've convinced ourselves that there really isn’t anything to be done.” —Philbert Dy

“The Parks are bafflingly naive and blissfully ignorant of the fact that their success and wealth is built off the backs of the invisible working class. This obliviousness and bewilderment to social and class inequities somehow make the Parks even more despicable than if they were to be pompous and arrogant about their privilege.

“This is not to say the Kims are made to be saints by virtue of the Parks’ ignorance. The Kims are relentless and conniving as they assimilate into the Park family, leeching off their wealth and privilege. But even as the Kims become increasingly convincing in their respective roles, the film questions whether they can truly fit within this higher class.” —Ethan

On how the film leaps geographical barriers:

“As a satire on social climbing and the aloofness of the upper class, it’s dead-on and has parallels to the American Dream that American viewers are unlikely to miss; as a dark comedy, it’s often laugh-aloud hilarious in its audacity; as a thriller, it has brilliantly executed moments of tension and surprises that genuinely caught me off guard; and as a drama about family dynamics, it has tender moments that stand out all the more because of how they’re juxtaposed with so much cynicism elsewhere in the film. Handling so many different tones is an immensely difficult balancing act, yet Bong handles all of it so skilfully that he makes it feel effortless.” —C. Roll

“One of the best things about it, I think, is the fact that I could honestly recommend it to anyone, even though I can't even try to describe it to someone. One may think, due to the picture’s academic praise and the general public’s misconceptions about foreign cinema, that this is some slow, artsy film for snobby cinephiles, but it’s quite the contrary: it’s entertaining, engaging and accessible from start to finish.” —Pedro Machado

On the performative nature of image:

“A família pobre que se infiltra no espaço da família rica trata a encenação—a dissimulação, os novos papéis que cada um desempenha—como uma espécie de luta de classes travada no palco das aparências. Uma luta de classes que usa a potência da imagem e do drama (os personagens escrevem os seus textos e mudam a sua aparência para passar por outras pessoas) como uma forma de reapropriação da propriedade e dos valores alheios.

“A grande proposta de Parasite é reconhecer que a ideia do conhecimento, consequentemente a natureza financeira e moral desse conhecimento, não passa de uma questão de performance. No capitalismo imediatista de hoje fingir saber é mais importante do que de fato saber.” —Arthur Tuoto

(Translation: “The poor family that infiltrates the rich family space treats the performance—the concealment, the new roles each plays—as a kind of class struggle waged on the stage of appearances. A class struggle that uses the power of image and drama (characters write their stories and change their appearance to pass for other people) as a form of reappropriation of the property and values of others.

“Parasite’s great proposal is to recognize that the idea of knowledge, therefore the financial and moral nature of that knowledge, is a matter of performance. In today’s immediate capitalism, pretending to know is more important than actually knowing.”)

Things you’re noticing on re-watches:

“Min and Mr. Park are both seen as powerful figures deserving of respect, and the way they dismissively respond to an earnest question about whether they truly care for the people they’re supposed to tells us a lot about how powerful people think about not just the people below them, but everyone in their lives.” —Demi Adejuyigbe

“When I first saw the trailer and saw Song Kang-ho in a Native American headdress I was a little taken aback. But the execution of the ideas, that these rich people will siphon off of everything, whether it’s poor people or disenfranchised cultures all the way across the world just to make their son happy, without properly taking the time to understand that culture, is pretty brilliant. I noticed a lot more subtlety with that specific example this time around.” —London

“I only noticed it on the second viewing, but the film opens and closes on the same shot. Socks are drying on a rack hanging in the semi-basement by the window. The camera pans down to a hopeful Ki-Woo sitting on his bed… if the film shows anything, it might be that the ways we usually approach ‘solving’ poverty and ‘fixing’ the class struggle often just reinforce how things have been since the beginning.” —Houston

The birth of the #BongHive

London-based writer and Letterboxd member Ella Kemp attended Cannes for Culture Whisper, and was waiting in the Parasite queue with fellow writers Karen Han and Iana Murray when the hashtag #BongHive was born. Letterboxd editor Gemma Gracewood asked her to recall that day.

Take us back to the day that #BongHive sprang into life.

Ella Kemp: I’m so glad you asked. Picture the scene: we were in the queue to watch the world premiere of Bong Joon-ho’s Parasite at Cannes. It was toward the end of the festival; Once Upon a Time in Hollywood had already screened…

Can you describe for our members what those film festival queues are like?

The queues in Cannes are very precise, and very strict and categorized. When you’re attending the festival as press, there are a number of different tiers that you can be assigned—white tier, pink tier, blue tier or yellow tier—and that’s the queue you have to stay in. And depending on which tier you’re in, a certain number of tiers will get into the film before you, no matter how late they arrive. Now, yellow is the lowest tier and it is the tier I was in this year. But, you know, I didn’t get shut out of any films I tried to go into, so I don’t want to speak ill of being yellow!

So, spirits are still high in the yellow queue before going to see Parasite. I was with friends and colleagues Iana Murray [writer for GQ, i-D, Much Ado About Cinema, Little White Lies], Karen Han [New York Times, Vanity Fair, Vulture, The Atlantic] and Jake Cunningham [of the Curzon and Ghibliotheque podcasts] who were also very excited for the film. We queued quite early, because obviously if you’re at the start of a queue and only two yellow tier people get in, you want that to be you.

So we had some time to spare, and we’re all very ‘online’ people and the 45 minutes in that queue was no different. So we just started tweeting, as you do. We thought, ‘Oh we’re just gonna tweet some stuff and see if it catches on.’ It might not, but at least we could kill some time.

So we just started tweeting #BongHive. And not explaining it too much.

#BongHive

— karen han (@karenyhan)

May 21, 2019

Within the realms of stan culture, I would argue that hashtags are more applicable to actors and musicians. Ariana Grande has her army of fans and they have their own hashtag. Justin Bieber has his, One Direction, all of them. But we thought, ‘You know who needs one and doesn’t have one right now? Bong Joon-ho.’

And so, you know, we tweeted it a couple of times, but I think what mattered the most was that there was no context, there was no logic, but there was consistency and insistence. So we tweeted it two or three times, and then the film started and we thought right, let’s see if this pays off. Because it could have been disappointing and we could have not wanted to be part of, you know, any kind of hype.

SMILE PRESIDENT @karenyhan #BongHive pic.twitter.com/Dk7T8bFYtv

— Ella Kemp (@ella_kemp)

May 21, 2019

But, Parasite was Parasite. So we walked out of it and thought, ‘Oh yes, the #BongHive is alive and kicking.’

I think what was interesting was that it came at that point in the festival when enthusiasm dipped. Everyone was very tired, and we were really tired, which is why we were tweeting illogical things. It was late at night by the time we came out of that film. It was close to midnight and we should have gone to bed, probably.

Because, first world problems, it is exhausting watching five, six, seven films a day at a film festival, trying to find sustenance that’s not popcorn, and form logical thoughts around these works of art.

Yes! It was nice to have fun with something. But what happened next was [Parasite distributor] Neon clocked it and went, ‘Oh wait, there’s something we can do there’. And then they took it, and it flew into the world, and now the #BongHive is worldwide.

I love the formality of Korean language and the way that South Koreans speak of their elders with such respect. I enjoyed being on the red carpet at TIFF hearing the Korean media refer to Bong Joon-ho as ‘Director Bong’.

It’s what he deserves!

I like to imagine a world where it’s ‘Director Gerwig’, ‘Director Campion’, ‘Director Sciamma’…

Exactly.

Related content:

Ella Kemp’s review of Parasite for Culture Whisper.

Letterboxd list: The directors Bong Joon-ho would like you to watch next.

Our interview with Director Bong, in which he reveals just how many times he’s watched Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho.

“I’m very awkward.” Bong Joon-ho’s first words following the standing ovation at Cannes for Parasite’s world premiere.

Karen Han interviews Director Bong for Polygon, with a particular interest in how he translated the film for non-Korean audiences. (Here’s Han’s original Parasite review out of Cannes; and here’s what happened when a translator asked her “Are you bong hive?” in front of the director.)

Haven’t seen Parasite yet? Here are the films recommended by Bong Joon-ho for you to watch in preparation.

With thanks to Matt Singer for the headline.

#bong joon-ho#bong hit#parasite#gisaengchung#cannes#palme d'or#the godfather#francis ford coppola#letterboxd#highest rated 2019#korean cinema#korean director#korean filmmakers#BONGHIVE#best of 2019#best of decade#highest rated film#ella kemp#david ehrlich#karen han#iana murray

147 notes

·

View notes

Text

Living in 2020

Who Would’ve Thought

Jacob Smith

Ok, before I start let me just be clear about a few things. I am not a medical expert, I know barely anything about medicine and I am still learning how to pronounce the prescriptions I’ve had for months. This story is opinion and a documentation of what I have witnessed and felt while living during COVID-19 and what I’ve heard in the news. This will be solely focusing on the journey that is living in a quarantine and social-distanced North American society and all of the added and subtracted rules and guidelines. This is satire, but enjoy.

March 2020, the month that shit got real. We were cool for the first 2 weeks of the month. Life was normal and we had no idea what was going to happen in the last two weeks, so we were living a blissful ignorance. COVID was showing up on a more regular basis but it hadn’t gotten to a point where the public was too cautious about it, as far as many people knew, it was an illness that could be rough when you get it, but nobody knew how you could get it and nobody thought they’d get it. They thought they could keep living their lives and it would fade away and just become another part of our world that we live with.

Little did we know COVID was climbing the ropes getting ready to give the population the peoples elbow and put us down for the count. In 2 weeks we went from blissful ignorance to “oh shit this is serious we got to get our shit together”. COVID hit the sports and entertainment world, the NBA being shut down led to other leagues following suit. Collegiate and other sports leagues stopped what they were doing, well known celebrities contracted the virus, the public had a collective oh shit moment and the world froze.

The middle of March started the journey of trying to figure out what the fuck was going on while also feeling like we knew what the fuck was going on. All we had to do was go inside our houses and only leave for necessities, for just 2 weeks and then life would go back to normal. Yeah we forgot to multiply that 2 weeks by what is now 26 and counting. So let’s talk about what we thought we knew.

Well first of all we thought and were told that it would be 2 weeks of everyone isolating and then we’d get back to normal. There’s a problem with that though, that's not how viruses work and we seemed to have forgotten not everybody is appreciative of rules. As soon as the isolation started, a group of people began rising up who were against the protocols that were put in place, let’s call them the “Fuck Your Rules Group”. These people seemed to be against all the protocols that were put in place by the government to protect people from this scary and unknown virus. They were preaching not distancing or isolating, they were living their life like nothing happened and they were stirring up the public.

The quarantined public, like an underdog in a title fight, refused to go down quietly, we were going to stick to our rules whether they liked it or not because we believed in them. We continued to isolate and distance while pleading to the Fuck Your Rules group that they should join us or else things could happen. Well, people didn't exactly follow the rules and like 5th graders who climb on top of the swing set at recess, we were sent to detention and the quarantine was extended another 2 weeks.

Well here we were, stuck in quarantine through April and the rules got tighter. Levels were created to designate areas to follow certain rules and across the country we were descending into total isolation. While we could still meet with a restricted group of people and socially distance which meant 6 feet of space between you and another person, we were told to wear masks over our mouths, or as some seemingly believed, over our chin and bottom lip.

You better talk to someone if you want to make sure you’re wearing the correct covering though. Not all face coverings are correct coverings and some completely disregard everything we’re wearing it for. Masks with ventilation appeared and were quickly deemed pointless by authorities and masks with not enough material between your mouth and the air around you were also deemed useless and we were told to get thicker masks. This wasn't the only time our mask and covering wearing was adjusted. Later on we were told to wear 2 masks for double the protection, and it would be harmless, unlike wearing 2 condoms for double that protection.

As 2020 ended and we were still in quarantine, we were told by the CDC that we should be pinching the masks at the top so they fit around our nose and leave little room for air to flow in along your nose. We were told N95 masks were the optimal mask but they ran out of stock very fast like when no tax is announced at a grocery store and your favorite canned meal is suddenly gone.

We can’t forget the period of time we were trying to figure out how exactly the virus transmits from person to person. People believed for a period of time that the virus could transmit through vision so eye contact was not suggested, that was quickly dismissed. There was a period of time where we were debating how long the virus can live on a surface, but we all assumed a long time so hand sanitizer became a hot commodity. People realized how important sanitization is and to my shock, people were surprised at how often hands should be washed, which made me question every hand I’ve shook prior to COVID. Everything was being washed, you’d swear our planet was an advertisement for Mr. Clean.

We were riding a wave of following guidelines that were created by people who claimed to be on top of things, and the people explaining those guidelines and the severity of whats happening differed rather greatly. This is where we get into the infamous number graphers. The people who got the number of active cases and other statistics from the government every day and reported it. Based on which news outlet you read and which source you followed, it would appear you would get two differing takes on what’s going on in society. People claimed graphers were purposely framing the numbers to make it worse than it is, and other people claimed that's what the graphers are supposed to do so we actually take this seriously and somehow get out of this within a relatively short period of time.

One news outlet told you that the world was descending into chaos and doomsday while another news outlet told you that you were just weeks away from being free if you actually followed the rules. It was a balancing game between reality and hope. Hope wasn't exactly easy to find at points, mostly because the feeling was progress would be made and then like someone who slips going up a hill, we’d roll back down, example being our push to flatten the curve up until September when the curve very much went the opposite way.

We fluttered between being determined to have this end, to feeling comfort in the way life was and just being cool with it for a while. We went from being able to gather with 50 people, to not being able to gather with anyone outside of your household, and for the most part we all tried to live by a “don’t leave your house unless its required” lifestyle. The Fuck Your Rules Group became more and more unsettled as the weeks went on but we the quarantined public still wouldn't collapse and we stuck to our beliefs of public health and safety.

Canadian thanksgiving, American thanksgiving, Halloween, Christmas, Valentines Day, all of the holidays came and went as we stayed isolated and knowing the priorities of people in society, we braced for a spike in cases after each holiday because we knew people weren’t going to let protocols get in the way of a fun time.

2020 ended and January 2021 started. This was the month we had all been waiting for as throughout the second half of 2020, the narrative of “we just need to get to 2021 and it will all be better” got rolling amongst the people. Yeah 2021 started and we very quickly realized not a whole lot got better. Cases were still an issue and numbers were rising and we still questioned if we really knew what we were doing like we had tried to convince ourselves. Well 3 months later into 2021 and March had come around again, and much to the dismay of basically everybody, quarantine, distancing and isolation still very much existed. Stay at home orders were sent and retracted for parts of Ontario and the isolation got to points more serious than it had been since COVID first reared its head a year prior.

Who knows when this will end, who knows what else we’ll be told to do and who knows what life will be like after but what we do know is we continue to live on being encouraged to have very minimal contact with other human beings and technology has been booming and will continue to boom. Living life in quarantine, isolation and in the year that is COVID-19. The world may never be what it was before, but the experiences of the last year will stay in the hearts and minds of everyone who was alive for this unprecedented time.

0 notes

Text

Coronavirus: The Hammer and the Dance

What the Next 18 Months Can Look Like, if Leaders Buy Us Time

This article follows Coronavirus: Why You Must Act Now, with over 40 million views and 30 translations. If you agree with this article, consider signing the corresponding White House petition. Translations available in 27 languages at the bottom. Running list of endorsements here. 5 million views so far.

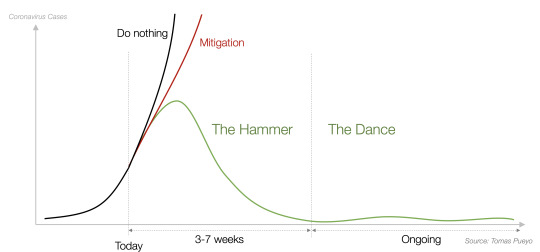

Summary of the article: Strong coronavirus measures today should only last a few weeks, there shouldn’t be a big peak of infections afterwards, and it can all be done for a reasonable cost to society, saving millions of lives along the way. If we don’t take these measures, tens of millions will be infected, many will die, along with anybody else that requires intensive care, because the healthcare system will have collapsed.

Within a week, countries around the world have gone from: “This coronavirus thing is not a big deal” to declaring the state of emergency. Yet many countries are still not doing much. Why?

Every country is asking the same question: How should we respond? The answer is not obvious to them.

Some countries, like France, Spain or Philippines, have since ordered heavy lockdowns. Others, like the US, UK, or Switzerland, have dragged their feet, hesitantly venturing into social distancing measures.

Here’s what we’re going to cover today, again with lots of charts, data and models with plenty of sources:

What’s the current situation?

What options do we have?

What’s the one thing that matters now: Time

What does a good coronavirus strategy look like?

How should we think about the economic and social impacts?

When you’re done reading the article, this is what you’ll take away:

Our healthcare system is already collapsing.

Countries have two options: either they fight it hard now, or they will suffer a massive epidemic.

If they choose the epidemic, hundreds of thousands will die. In some countries, millions.

And that might not even eliminate further waves of infections.

If we fight hard now, we will curb the deaths.

We will relieve our healthcare system.

We will prepare better.

We will learn.

The world has never learned as fast about anything, ever.

And we need it, because we know so little about this virus.

All of this will achieve something critical: Buy Us Time.

If we choose to fight hard, the fight will be sudden, then gradual.

We will be locked in for weeks, not months.

Then, we will get more and more freedoms back.

It might not be back to normal immediately.

But it will be close, and eventually back to normal.

And we can do all that while considering the rest of the economy too.

Ok, let’s do this.

1. What’s the situation?

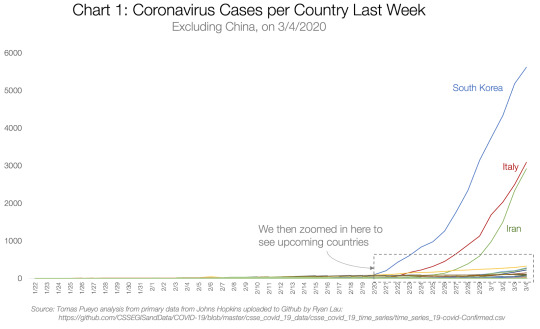

Last week, I showed this curve:

It showed coronavirus cases across the world outside of China. We could only discern Italy, Iran and South Korea. So I had to zoom in on the bottom right corner to see the emerging countries. My entire point is that they would soon be joining these 3 cases.

Let’s see what has happened since.

It showed coronavirus cases across the world outside of China. We could only discern Italy, Iran and South Korea. So I had to zoom in on the bottom right corner to see the emerging countries. My entire point is that they would soon be joining these 3 cases.

Let’s see what has happened since.

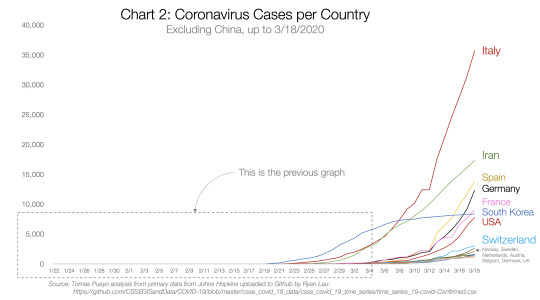

As predicted, the number of cases has exploded in dozens of countries. Here, I was forced to show only countries with over 1,000 cases. A few things to note:

Spain, Germany, France and the US all have more cases than Italy when it ordered the lockdown

An additional 16 countries have more cases today than Hubei when it went under lockdown: Japan, Malaysia, Canada, Portugal, Australia, Czechia, Brazil and Qatar have more than Hubei but below 1,000 cases. Switzerland, Sweden, Norway, Austria, Belgium, Netherlands and Denmark all have above 1,000 cases.

Do you notice something weird about this list of countries? Outside of China and Iran, which have suffered massive, undeniable outbreaks, and Brazil and Malaysia, every single country in this list is among the wealthiest in the world.

Do you think this virus targets rich countries? Or is it more likely that rich countries are better able to identify the virus?

It’s unlikely that poorer countries aren’t touched. Warm and humid weather probably helps, but doesn’t prevent an outbreak by itself — otherwise Singapore, Malaysia or Brazil wouldn’t be suffering outbreaks.

The most likely interpretations are that the coronavirus either took longer to reach these countries because they’re less connected, or it’s already there but these countries haven’t been able to invest enough on testing to know.

Either way, if this is true, it means that most countries won’t escape the coronavirus. It’s a matter of time before they see outbreaks and need to take measures.

What measures can different countries take?

2. What Are Our Options?

Since the article last week, the conversation has changed and many countries have taken measures. Here are some of the most illustrative examples:

Measures in Spain and France

In one extreme, we have Spain and France. This is the timeline of measures for Spain:

On Thursday, 3/12, the President dismissed suggestions that the Spanish authorities had been underestimating the health threat.

On Friday, they declared the State of Emergency.

On Saturday, measures were taken:

People can’t leave home except for key reasons: groceries, work, pharmacy, hospital, bank or insurance company (extreme justification)

Specific ban on taking kids out for a walk or seeing friends or family (except to take care of people who need help, but with hygiene and physical distance measures)

All bars and restaurants closed. Only take-home acceptable.

All entertainment closed: sports, movies, museums, municipal celebrations…

Weddings can’t have guests. Funerals can’t have more than a handful of people.

Mass transit remains open

On Monday, land borders were shut.

Some people see this as a great list of measures. Others put their hands up in the air and cry of despair. This difference is what this article will try to reconcile.

France’s timeline of measures is similar, except they took more time to apply them, and they are more aggressive now. For example, rent, taxes and utilities are suspended for small businesses.

Measures in the US and UK

The US and UK, like countries such as Switzerland, have dragged their feet in implementing measures. Here’s the timeline for the US:

Wednesday 3/11: travel ban.

Friday: National Emergency declared. No social distancing measures

Monday: the government urges the public to avoid restaurants or bars and attend events with more than 10 people. No social distancing measure is actually enforceable. It’s just a suggestion.

Lots of states and cities are taking the initiative and mandating much stricter measures.

The UK has seen a similar set of measures: lots of recommendations, but very few mandates.

These two groups of countries illustrate the two extreme approaches to fight the coronavirus: mitigation and suppression. Let’s understand what they mean.

Option 1: Do Nothing

Before we do that, let’s see what doing nothing would entail for a country like the US:

This fantastic epidemic calculator can help you understand what will happen under different scenarios. I’ve pasted below the graph the key factors that determine the behavior of the virus. Note that infected, in pink, peak in the tens of millions at a certain date. Most variables have been kept from the default. The only material changes are R from 2.2 to 2.4 (corresponds better to currently available information. See at the bottom of the epidemic calculator), fatality rate (4% due to healthcare system collapse. See details below or in the previous article), length of hospital stay (down from 20 to 10 days) and hospitalization rate (down from 20% to 14% based on severe and critical cases. Note the WHO calls out a 20% rate) based on our most recently available gathering of research. Note that these numbers don’t change results much. The only change that matters is the fatality rate.

If we do nothing: Everybody gets infected, the healthcare system gets overwhelmed, the mortality explodes, and ~10 million people die (blue bars). For the back-of-the-envelope numbers: if ~75% of Americans get infected and 4% die, that’s 10 million deaths, or around 25 times the number of US deaths in World War II.

You might wonder: “That sounds like a lot. I’ve heard much less than that!”

So what’s the catch? With all these numbers, it’s easy to get confused. But there’s only two numbers that matter: What share of people will catch the virus and fall sick, and what share of them will die. If only 25% are sick (because the others have the virus but don’t have symptoms so aren’t counted as cases), and the fatality rate is 0.6% instead of 4%, you end up with 500k deaths in the US.

If we don’t do anything, the number of deaths from the coronavirus will probably land between these two numbers. The chasm between these extremes is mostly driven by the fatality rate, so understanding it better is crucial. What really causes the coronavirus deaths?

How Should We Think about the Fatality Rate?

This is the same graph as before, but now looking at hospitalized people instead of infected and dead:

The light blue area is the number of people who would need to go to the hospital, and the darker blue represents those who need to go to the intensive care unit (ICU). You can see that number would peak at above 3 million.

Now compare that to the number of ICU beds we have in the US (50k today, we could double that repurposing other space). That’s the red dotted line.

No, that’s not an error.

That red dotted line is the capacity we have of ICU beds. Everyone above that line would be in critical condition but wouldn’t be able to access the care they need, and would likely die.

Instead of ICU beds you can also look at ventilators, but the result is broadly the same, since there are fewer than 100k ventilators in the US.

This is why people died in droves in Hubei and are now dying in droves in Italy and Iran. The Hubei fatality rate ended up better than it could have been because they built 2 hospitals nearly overnight. Italy and Iran can’t do the same; few, if any, other countries can. We’ll see what ends up happening there.

So why is the fatality rate close to 4%?

If 5% of your cases require intensive care and you can’t provide it, most of those people die. As simple as that.

Additionally, recent data suggests that US cases are more severe than in China.

I wish that was all, but it isn’t.

Collateral Damage

These numbers only show people dying from coronavirus. But what happens if all your healthcare system is collapsed by coronavirus patients? Others also die from other ailments.

What happens if you have a heart attack but the ambulance takes 50 minutes to come instead of 8 (too many coronavirus cases) and once you arrive, there’s no ICU and no doctor available? You die.

There are 4 million admissions to the ICU in the US every year, and 500k (~13%) of them die. Without ICU beds, that share would likely go much closer to 80%. Even if only 50% died, in a year-long epidemic you go from 500k deaths a year to 2M, so you’re adding 1.5M deaths, just with collateral damage.

If the coronavirus is left to spread, the US healthcare system will collapse, and the deaths will be in the millions, maybe more than 10 million.

The same thinking is true for most countries. The number of ICU beds and ventilators and healthcare workers are usually similar to the US or lower in most countries. Unbridled coronavirus means healthcare system collapse, and that means mass death.

Unbridled coronavirus means healthcare systems collapse, and that means mass death.

By now, I hope it’s pretty clear we should act. The two options that we have are mitigation and suppression. Both of them propose to “flatten the curve”, but they go about it very differently.

Option 2: Mitigation Strategy

Mitigation goes like this: “It’s impossible to prevent the coronavirus now, so let’s just have it run its course, while trying to reduce the peak of infections. Let’s just flatten the curve a little bit to make it more manageable for the healthcare system.”

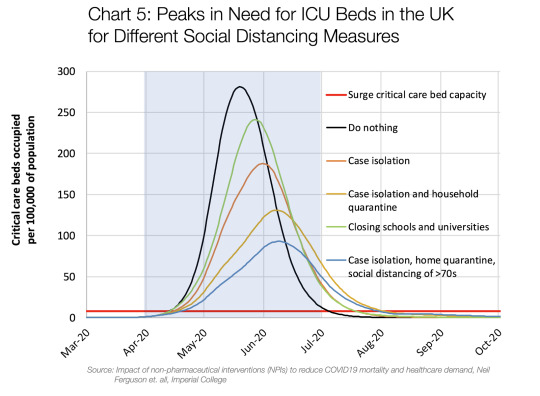

This chart appears in a very important paper published over the weekend from the Imperial College London. Apparently, it pushed the UK and US governments to change course.

It’s a very similar graph as the previous one. Not the same, but conceptually equivalent. Here, the “Do Nothing” situation is the black curve. Each one of the other curves are what would happen if we implemented tougher and tougher social distancing measures. The blue one shows the toughest social distancing measures: isolating infected people, quarantining people who might be infected, and secluding old people. This blue line is broadly the current UK coronavirus strategy, although for now they’re just suggesting it, not mandating it.

Here, again, the red line is the capacity for ICUs, this time in the UK. Again, that line is very close to the bottom. All that area of the curve on top of that red line represents coronavirus patients who would mostly die because of the lack of ICU resources.

Not only that, but by flattening the curve, the ICUs will collapse for months, increasing collateral damage.

You should be shocked. When you hear: “We’re going to do some mitigation” what they’re really saying is: “We will knowingly overwhelm the healthcare system, driving the fatality rate up by a factor of 10x at least.”

You would imagine this is bad enough. But we’re not done yet. Because one of the key assumptions of this strategy is what’s called “Herd Immunity”.

Herd Immunity and Virus Mutation

The idea is that all the people who are infected and then recover are now immune to the virus. This is at the core of this strategy: “Look, I know it’s going to be hard for some time, but once we’re done and a few million people die, the rest of us will be immune to it, so this virus will stop spreading and we’ll say goodbye to the coronavirus. Better do it at once and be done with it, because our alternative is to do social distancing for up to a year and risk having this peak happen later anyways.”

Except this assumes one thing: the virus doesn’t change too much. If it doesn’t change much, then lots of people do get immunity, and at some point the epidemic dies down

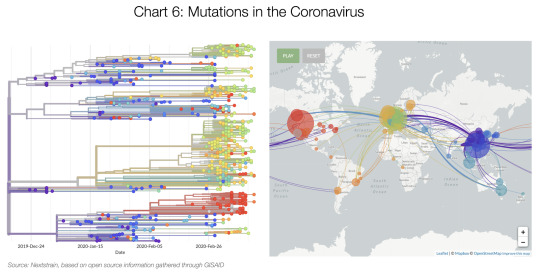

How likely is this virus to mutate?

It seems it already has.

This graph represents the different mutations of the virus. You can see that the initial strains started in purple in China and then spread. Each time you see a branching on the left graph, that is a mutation leading to a slightly different variant of the virus.

This should not be surprising: RNA-based viruses like the coronavirus or the flu tend to mutate around 100 times faster than DNA-based ones—although the coronavirus mutates more slowly than influenza viruses.

Not only that, but the best way for this virus to mutate is to have millions of opportunities to do so, which is exactly what a mitigation strategy would provide: hundreds of millions of people infected.

That’s why you have to get a flu shot every year. Because there are so many flu strains, with new ones always evolving, the flu shot can never protect against all strains.

Put in another way: the mitigation strategy not only assumes millions of deaths for a country like the US or the UK. It also gambles on the fact that the virus won’t mutate too much — which we know it does. And it will give it the opportunity to mutate. So once we’re done with a few million deaths, we could be ready for a few million more — every year. This corona virus could become a recurring fact of life, like the flu, but many times deadlier.

The best way for this virus to mutate is to have millions of opportunities to do so, which is exactly what a mitigation strategy would provide.

So if neither doing nothing and mitigation will work, what’s the alternative? It’s called suppression.

Option 3: Suppression Strategy

The Mitigation Strategy doesn’t try to contain the epidemic, just flatten the curve a bit. Meanwhile, the Suppression Strategy tries to apply heavy measures to quickly get the epidemic under control. Specifically:

Go hard right now. Order heavy social distancing. Get this thing under control.

Then, release the measures, so that people can gradually get back their freedoms and something approaching normal social and economic life can resume.

What does that look like?

All the model parameters are the same, except that there is an intervention around now to reduce the transmission rate to R=0.62, and because the healthcare system isn’t collapsed, the fatality rate goes down to 0.6%. I defined “around now” as having ~32,000 cases when implementing the measures (3x the official number as of today, 3/19). Note that this is not too sensitive to the R chosen. An R of 0.98 for example shows 15,000 deaths. Five times more than with an R of 0.62, but still tens of thousands of deaths and not millions. It’s also not too sensitive to the fatality rate: if it’s 0.7% instead of 0.6%, the death toll goes from 15,000 to 17,000. It’s the combination of a higher R, a higher fatality rate, and a delay in taking measures that explodes the number of fatalities. That’s why we need to take measures to reduce R today. For clarification, the famous R0 is R at the beginning (R at time 0). It’s the transmission rate when nobody is immune yet and there are no measures against it taken. R is the overall transmission rate.

Under a suppression strategy, after the first wave is done, the death toll is in the thousands, and not in the millions.

Why? Because not only do we cut the exponential growth of cases. We also cut the fatality rate since the healthcare system is not completely overwhelmed. Here, I used a fatality rate of 0.9%, around what we’re seeing in South Korea today, which has been most effective at following Suppression Strategy.

Said like this, it sounds like a no-brainer. Everybody should follow the Suppression Strategy.

So why do some governments hesitate?

They fear three things:

This first lockdown will last for months, which seems unacceptable for many people.

A months-long lockdown would destroy the economy.

It wouldn’t even solve the problem, because we would be just postponing the epidemic: later on, once we release the social distancing measures, people will still get infected in the millions and die.

Here is how the Imperial College team modeled suppressions. The green and yellow lines are different scenarios of Suppression. You can see that doesn’t look good: We still get huge peaks, so why bother?

We’ll get to these questions in a moment, but there’s something more important before.

This is completely missing the point.

Presented like these, the two options of Mitigation and Suppression, side by side, don’t look very appealing. Either a lot of people die soon and we don’t hurt the economy today, or we hurt the economy today, just to postpone the deaths.

This ignores the value of time.

3. The Value of Time

In our previous post, we explained the value of time in saving lives. Every day, every hour we waited to take measures, this exponential threat continued spreading. We saw how a single day could reduce the total cases by 40% and the death toll by even more.

But time is even more valuable than that.

We’re about to face the biggest wave of pressure on the healthcare system ever seen in history. We are completely unprepared, facing an enemy we don’t know. That is not a good position for war.

What if you were about to face your worst enemy, of which you knew very little, and you had two options: Either you run towards it, or you escape to buy yourself a bit of time to prepare. Which one would you choose?

This is what we need to do today. The world has awakened. Every single day we delay the coronavirus, we can get better prepared. The next sections detail what that time would buy us:

Lower the Number of Cases

With effective suppression, the number of true cases would plummet overnight, as we saw in Hubei last week.

As of today, there are 0 daily new cases of coronavirus in the entire 60 million-big region of Hubei.

The diagnostics would keep going up for a couple of weeks, but then they would start going down. With fewer cases, the fatality rate starts dropping too. And the collateral damage is also reduced: fewer people would die from non-coronavirus-related causes because the healthcare system is simply overwhelmed.

Suppression would get us:

Fewer total cases of Coronavirus

Immediate relief for the healthcare system and the humans who run it

Reduction in fatality rate

Reduction in collateral damage

Ability for infected, isolated and quarantined healthcare workers to get better and back to work. In Italy, healthcare workers represent 8% of all contagions.

Understand the True Problem: Testing and Tracing

Right now, the UK and the US have no idea about their true cases. We don’t know how many there are. We just know the official number is not right, and the true one is in the tens of thousands of cases. This has happened because we’re not testing, and we’re not tracing.

With a few more weeks, we could get our testing situation in order, and start testing everybody. With that information, we would finally know the true extent of the problem, where we need to be more aggressive, and what communities are safe to be released from a lockdown.

New testing methods could speed up testing and drive costs down substantially.

We could also set up a tracing operation like the ones they have in China or other East Asia countries, where they can identify all the people that every sick person met, and can put them in quarantine. This would give us a ton of intelligence to release later on our social distancing measures: if we know where the virus is, we can target these places only. This is not rocket science: it’s the basics of how East Asia Countries have been able to control this outbreak without the kind of draconian social distancing that is increasingly essential in other countries.

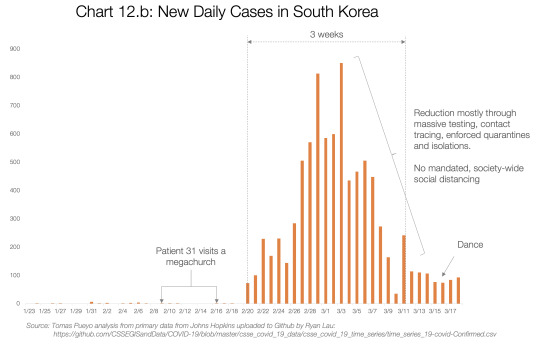

The measures from this section (testing and tracing) single-handedly curbed the growth of the coronavirus in South Korea and got the epidemic under control, without a strong imposition of social distancing measures.

Build Up Capacity

The US (and presumably the UK) are about to go to war without armor.

We have masks for just two weeks, few personal protective equipments (“PPE”), not enough ventilators, not enough ICU beds, not enough ECMOs (blood oxygenation machines)… This is why the fatality rate would be so high in a mitigation strategy.

But if we buy ourselves some time, we can turn this around:

We have more time to buy equipment we will need for a future wave

We can quickly build up our production of masks, PPEs, ventilators, ECMOs, and any other critical device to reduce fatality rate.

Put in another way: we don’t need years to get our armor, we need weeks. Let’s do everything we can to get our production humming now. Countries are mobilized. People are being inventive, such as using 3D printing for ventilator parts. We can do it. We just need more time. Would you wait a few weeks to get yourself some armor before facing a mortal enemy?

This is not the only capacity we need. We will need health workers as soon as possible. Where will we get them? We need to train people to assist nurses, and we need to get medical workers out of retirement. Many countries have already started, but this takes time. We can do this in a few weeks, but not if everything collapses.

Lower Public Contagiousness

The public is scared. The coronavirus is new. There’s so much we don’t know how to do yet! People haven’t learned to stop hand-shaking. They still hug. They don’t open doors with their elbow. They don’t wash their hands after touching a door knob. They don’t disinfect tables before sitting.

Once we have enough masks, we can use them outside of the healthcare system too. Right now, it’s better to keep them for healthcare workers. But if they weren’t scarce, people should wear them in their daily lives, making it less likely that they infect other people when sick, and with proper training also reducing the likelihood that the wearers get infected. (In the meantime, wearing something is better than nothing.)

All of these are pretty cheap ways to reduce the transmission rate. The less this virus propagates, the fewer measures we’ll need in the future to contain it. But we need time to educate people on all these measures and equip them.

Understand the Virus

We know very very little about the virus. But every week, hundreds of new papers are coming.

The world is finally united against a common enemy. Researchers around the globe are mobilizing to understand this virus better.

How does the virus spread?

How can contagion be slowed down?

What is the share of asymptomatic carriers?

Are they contagious? How much?

What are good treatments?

How long does it survive?

On what surfaces?

How do different social distancing measures impact the transmission rate?

What’s their cost?

What are tracing best practices?

How reliable are our tests?

Clear answers to these questions will help make our response as targeted as possible while minimizing collateral economic and social damage. And they will come in weeks, not years.

Find Treatments

Not only that, but what if we found a treatment in the next few weeks? Any day we buy gets us closer to that. Right now, there are already several candidates, such as Favipiravir, Chloroquine, or Chloroquine combined with Azithromycin. What if it turned out that in two months we discovered a treatment for the coronavirus? How stupid would we look if we already had millions of deaths following a mitigation strategy?

Understand the Cost-Benefits

All of the factors above can help us save millions of lives. That should be enough. Unfortunately, politicians can’t only think about the lives of the infected. They must think about all the population, and heavy social distancing measures have an impact on others.

Right now we have no idea how different social distancing measures reduce transmission. We also have no clue what their economic and social costs are.

Isn’t it a bit difficult to decide what measures we need for the long term if we don’t know their cost or benefit?

A few weeks would give us enough time to start studying them, understand them, prioritize them, and decide which ones to follow.

Fewer cases, more understanding of the problem, building up assets, understanding the virus, understanding the cost-benefit of different measures, educating the public… These are some core tools to fight the virus, and we just need a few weeks to develop many of them. Wouldn’t it be dumb to commit to a strategy that throws us instead, unprepared, into the jaws of our enemy?

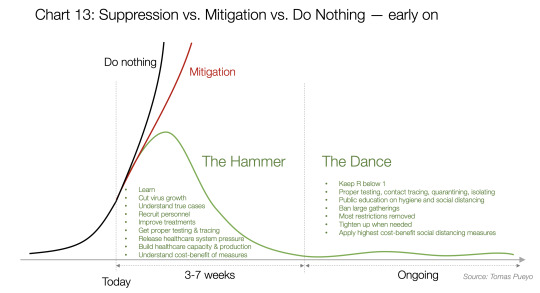

4. The Hammer and the Dance

Now we know that the Mitigation Strategy is probably a terrible choice, and that the Suppression Strategy has a massive short-term advantage.

But people have rightful concerns about this strategy:

How long will it actually last?

How expensive will it be?

Will there be a second peak as big as if we didn’t do anything?

Here, we’re going to look at what a true Suppression Strategy would look like. We can call it the Hammer and the Dance.

The Hammer

First, you act quickly and aggressively. For all the reasons we mentioned above, given the value of time, we want to quench this thing as soon as possible.

One of the most important questions is: How long will this last?

The fear that everybody has is that we will be locked inside our homes for months at a time, with the ensuing economic disaster and mental breakdowns. This idea was unfortunately entertained in the famous Imperial College paper:

Do you remember this chart? The light blue area that goes from end of March to end of August is the period that the paper recommends as the Hammer, the initial suppression that includes heavy social distancing.

If you’re a politician and you see that one option is to let hundreds of thousands or millions of people die with a mitigation strategy and the other is to stop the economy for five months before going through the same peak of cases and deaths, these don’t sound like compelling options.

But this doesn’t need to be so. This paper, driving policy today, has been brutally criticized for core flaws: They ignore contact tracing (at the core of policies in South Korea, China or Singapore among others) or travel restrictions (critical in China), ignore the impact of big crowds…

The time needed for the Hammer is weeks, not months.

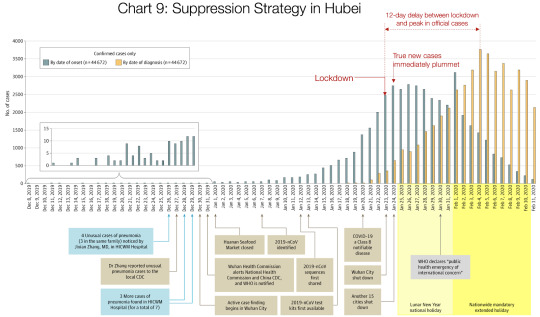

This graph shows the new cases in the entire Hubei region (60 million people) every day since 1/23. Within 2 weeks, the country was starting to get back to work. Within ~5 weeks it was completely under control. And within 7 weeks the new diagnostics was just a trickle. Let’s remember this was the worst region in China.

Remember again that these are the orange bars. The grey bars, the true cases, had plummeted much earlier (see Chart 9).

The measures they took were pretty similar to the ones taken in Italy, Spain or France: isolations, quarantines, people had to stay at home unless there was an emergency or had to buy food, contact tracing, testing, more hospital beds, travel bans…

Details matter, however.

China’s measures were stronger. For example, people were limited to one person per household allowed to leave home every three days to buy food. Also, their enforcement was severe. It is likely that this severity stopped the epidemic faster.

In Italy, France and Spain, measures were not as drastic, and their implementation is not as tough. People still walk on the streets, many without masks. This is likely to result in a slower Hammer: more time to fully control the epidemic.

Some people interpret this as “Democracies will never be able to replicate this reduction in cases”. That’s wrong.

For several weeks, South Korea had the worst epidemic outside of China. Now, it’s largely under control. And they did it without asking people to stay home. They achieved it mostly with very aggressive testing, contact tracing, and enforced quarantines and isolations.

The following table gives a good sense of what measures different countries have followed, and how that has impacted them (this is a work-in-progress. Feedback welcome.)

This shows how countries who were prepared, with stronger epidemiological authority, education on hygiene and social distancing, and early detection and isolation, didn’t have to pay with heavier measures afterwards.

Conversely, countries like Italy, Spain or France weren’t doing these well, and had to then apply the Hammer with the hard measures at the bottom to catch up.

The lack of measures in the US and UK is in stark contrast, especially in the US. These countries are still not doing what allowed Singapore, South Korea or Taiwan to control the virus, despite their outbreaks growing exponentially. But it’s a matter of time. Either they have a massive epidemic, or they realize late their mistake, and have to overcompensate with a heavier Hammer. There is no escape from this.

But it’s doable. If an outbreak like South Korea’s can be controlled in weeks and without mandated social distancing, Western countries, which are already applying a heavy Hammer with strict social distancing measures, can definitely control the outbreak within weeks. It’s a matter of discipline, execution, and how much the population abides by the rules.

Once the Hammer is in place and the outbreak is controlled, the second phase begins: the Dance.

The Dance

If you hammer the coronavirus, within a few weeks you’ve controlled it and you’re in much better shape to address it. Now comes the longer-term effort to keep this virus contained until there’s a vaccine.

This is probably the single biggest, most important mistake people make when thinking about this stage: they think it will keep them home for months. This is not the case at all. In fact, it is likely that our lives will go back to close to normal.

The Dance in Successful Countries

How come South Korea, Singapore, Taiwan and Japan have had cases for a long time, in the case of South Korea thousands of them, and yet they’re not locked down home?

Coronavirus: South Korea seeing a 'stabilising trend'

South Korea's Foreign Minister, Kang Kyung-wha, says she thinks early testing has been the key to South Korea's low…

www.bbc.com

In this video, the South Korea Foreign Minister explains how her country did it. It was pretty simple: efficient testing, efficient tracing, travel bans, efficient isolating and efficient quarantining.

This paper explains Singapore’s approach:

Interrupting transmission of COVID-19: lessons from containment efforts in Singapore

Highlight. Despite multiple importations resulting in local chains of transmission, Singapore has been able to control…

academic.oup.com

Want to guess their measures? The same ones as in South Korea. In their case, they complemented with economic help to those in quarantine and travel bans and delays.

Is it too late for these countries and others? No. By applying the Hammer, they’re getting a new chance, a new shot at doing this right. The more they wait, the heavier and longer the hammer, but it can control the epidemics.

But what if all these measures aren’t enough?

The Dance of R

I call the months-long period between the Hammer and a vaccine or effective treatment the Dance because it won’t be a period during which measures are always the same harsh ones. Some regions will see outbreaks again, others won’t for long periods of time. Depending on how cases evolve, we will need to tighten up social distancing measures or we will be able to release them. That is the dance of R: a dance of measures between getting our lives back on track and spreading the disease, one of economy vs. healthcare.

How does this dance work?

It all turns around the R. If you remember, it’s the transmission rate. Early on in a standard, unprepared country, it’s somewhere between 2 and 3: During the few weeks that somebody is infected, they infect between 2 and 3 other people on average.

If R is above 1, infections grow exponentially into an epidemic. If it’s below 1, they die down.

During the Hammer, the goal is to get R as close to zero, as fast as possible, to quench the epidemic. In Wuhan, it is calculated that R was initially 3.9, and after the lockdown and centralized quarantine, it went down to 0.32.

But once you move into the Dance, you don’t need to do that anymore. You just need your R to stay below 1: a lot of the social distancing measures have true, hard costs on people. They might lose their job, their business, their healthy habits…

You can remain below R=1 with a few simple measures.

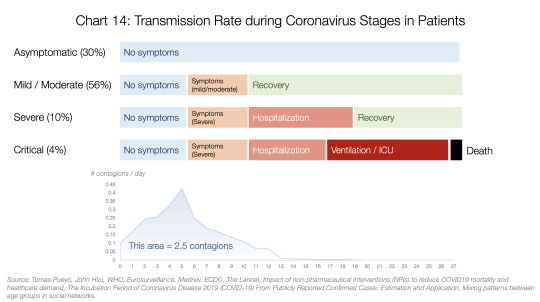

This is an approximation of how different types of patients respond to the virus, as well as their contagiousness. Nobody knows the true shape of this curve, but we’ve gathered data from different papers to approximate how it looks like.

Every day after they contract the virus, people have some contagion potential. Together, all these days of contagion add up to 2.5 contagions on average.

It is believed that there are some contagions already happening during the “no symptoms” phase. After that, as symptoms grow, usually people go to the doctor, get diagnosed, and their contagiousness diminishes.

For example, early on you have the virus but no symptoms, so you behave as normal. When you speak with people, you spread the virus. When you touch your nose and then open door knob, the next people to open the door and touch their nose get infected.

The more the virus is growing inside you, the more infectious you are. Then, once you start having symptoms, you might slowly stop going to work, stay in bed, wear a mask, or start going to the doctor. The bigger the symptoms, the more you distance yourself socially, reducing the spread of the virus.

Once you’re hospitalized, even if you are very contagious you don’t tend to spread the virus as much since you’re isolated.

This is where you can see the massive impact of policies like those of Singapore or South Korea:

If people are massively tested, they can be identified even before they have symptoms. Quarantined, they can’t spread anything.

If people are trained to identify their symptoms earlier, they reduce the number of days in blue, and hence their overall contagiousness

If people are isolated as soon as they have symptoms, the contagions from the orange phase disappear.

If people are educated about personal distance, mask-wearing, washing hands or disinfecting spaces, they spread less virus throughout the entire period.

Only when all these fail do we need heavier social distancing measures.

The ROI of Social Distancing

If with all these measures we’re still way above R=1, we need to reduce the average number of people that each person meets.

There are some very cheap ways to do that, like banning events with more than a certain number of people (eg, 50, 500), or asking people to work from home when they can.

Other are much, much more expensive economically, socially and ethically, such as closing schools and universities, asking everybody to stay home, or closing businesses.

This chart is made up because it doesn’t exist today. Nobody has done enough research about this or put together all these measures in a way that can compare them.

It’s unfortunate, because it’s the single most important chart that politicians would need to make decisions. It illustrates what is really going through their minds.

During the Hammer period, politicians want to lower R as much as possible, through measures that remain tolerable for the population. In Hubei, they went all the way to 0.32. We might not need that: maybe just to 0.5 or 0.6.

But during the Dance of the R period, they want to hover as close to 1 as possible, while staying below it over the long term term. That prevents a new outbreak, while eliminating the most drastic measures.

What this means is that, whether leaders realize it or not, what they’re doing is:

List all the measures they can take to reduce R

Get a sense of the benefit of applying them: the reduction in R

Get a sense of their cost: the economic, social, and ethical cost.

Stack-rank the initiatives based on their cost-benefit

Pick the ones that give the biggest R reduction up till 1, for the lowest cost.

This is for illustrative purposes only. All data is made up. However, as far as we were able to tell, this data doesn’t exist today. It needs to. For example, the list from the CDC is a great start, but it misses things like education measures, triggers, quantifications of costs and benefits, measure details, economic / social countermeasures…

Initially, their confidence on these numbers will be low. But that‘s still how they are thinking—and should be thinking about it.

What they need to do is formalize the process: Understand that this is a numbers game in which we need to learn as fast as possible where we are on R, the impact of every measure on reducing R, and their social and economic costs.

Only then will they be able to make a rational decision on what measures they should take.

Conclusion: Buy Us Time

The coronavirus is still spreading nearly everywhere. 152 countries have cases. We are against the clock. But we don’t need to be: there’s a clear way we can be thinking about this.

Some countries, especially those that haven’t been hit heavily yet by the coronavirus, might be wondering: Is this going to happen to me? The answer is: It probably already has. You just haven’t noticed. When it really hits, your healthcare system will be in even worse shape than in wealthy countries where the healthcare systems are strong. Better safe than sorry, you should consider taking action now.

For the countries where the coronavirus is already here, the options are clear.

On one side, countries can go the mitigation route: create a massive epidemic, overwhelm the healthcare system, drive the death of millions of people, and release new mutations of this virus in the wild.

On the other, countries can fight. They can lock down for a few weeks to buy us time, create an educated action plan, and control this virus until we have a vaccine.

Governments around the world today, including some such as the US, the UK or Switzerland have so far chosen the mitigation path.

That means they’re giving up without a fight. They see other countries having successfully fought this, but they say: “We can’t do that!”

What if Churchill had said the same thing? “Nazis are already everywhere in Europe. We can’t fight them. Let’s just give up.” This is what many governments around the world are doing today. They’re not giving you a chance to fight this. You have to demand it.

Share the Word

Unfortunately, millions of lives are still at stake. Share this article—or any similar one—if you think it can change people’s opinion. Leaders need to understand this to avert a catastrophe. The moment to act is now.

Source: Medium.com

Read the full article

0 notes

Text

Art Basel Miami, Where Big Money Meets Bigger Money

MIAMI BEACH — As the global art world descends on South Florida for next week’s Art Basel fair, which is celebrating its 17th anniversary, it’s worth remembering how truly small the art world once was.

As late as the 1980s, you could fit contemporary art’s A-list players all in one room. And the room in question often belonged to the prominent collectors Don and Mera Rubell — inside their Manhattan townhouse, then the de facto after-party venue for the Whitney Museum of American Art’s career-launching biennials. “We knew every collector in the world then,” Don Rubell recalled with a chuckle. “Ninety percent of them were in New York or Germany.”

Richard Prince was a fresh arrival to the Rubells’ after-party in 1985, having made his biennial debut that year with his signature photo appropriations. He would later write of his nervous excitement at threading his way into their gathering, past the reigning enfant terrible Robert Mapplethorpe, and spying his own artwork there. “It was the first time I’d ever seen anything of mine hung on someone else’s wall,” an awed Mr. Prince remembered. “I was still an outsider but that evening I felt, if only for a moment, part of another family.”

That family of artists, museum directors, curators and collectors is now exponentially larger, with far more money, and far more rungs of status up for grabs. But the Rubells are just as keen on occupying its center stage as they were in 1993, when they purchased a 40,000-square-foot warehouse for their growing art collection in the Wynwood neighborhood of Miami. They later became instrumental in wooing the Swiss-based Art Basel fair to begin a Miami edition.

Now they have enlarged the showcase for their 7,200 artworks. Opening Dec. 4, the Rubell Family Collection, rechristened the Rubell Museum, fills a 100,000-square-foot campus just west, in the new art neighborhood of Allapattah — a gritty mix of warehouses, hospitals and modest homes. The Annabelle Selldorf-designed complex includes a restaurant, bookstore, event space, outdoor garden, and not least, contemporary art holdings that overshadow that of any other South Florida institution.

Allapattah’s cheaper real estate beckoned: The Rubells bought their new museum’s lot for $4 million, and purchased a similarly sized lot across the street for $8.6 million. Several heavy-hitting developers have also moved into Allapattah, mirroring a pattern of gentrification that saw property values skyrocket in Wynwood (and forced artists to move out). While Mrs. Rubell insisted this move wasn’t simply about flipping properties, she admitted “the appreciated value of the Wynwood space is why we can now do all this.” Valued by Miami-Dade County at $12 million, its planned sale is likely to fetch upward of twice that.

The family still runs the same nonprofit organization to exhibit their collection, which remains open to the public five days a week. So why now call it a museum? Is it about bragging rights? “It’s about what we want to step up to,” Mrs. Rubell said. “I meet people who say to me ‘I always wanted to come, but I didn’t know how to get an invitation.’ Here we are today, open to the public, doing all these exhibitions, and people still feel it’s not accessible. But everybody knows what a museum is.”

The Rubell Museum’s debut exhibition is “a hit parade of the last 50 years of contemporary art: Keith Haring, Jeff Koons, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Andy Warhol, Richard Prince, Cindy Sherman, all the favorites,” Mera Rubell explained. “If you’ve been scratching your head for the last 50 years saying ‘What the hell is all this crap?’, well that stuff is now worth $100 million. But never mind the money. We’re talking about the art that defined a generation.” So rather than dismissively rolling your eyes, she continued, “you can say ‘Wow, this is teaching me something about the world we live in’!”

That teachable lesson, for better or for worse, will be on full display throughout Miami next week. Below is a guide to the highlights.

So how do I attend the Art Basel Miami Beach fair?

Staged annually inside Miami Beach’s Convention Center, entrance is as easy as buying a ticket on site. (Although at $65 a ticket, it’s pricey window-shopping.)

What exactly is the difference between Art Basel Miami Beach and Miami Art Week?

The Art Basel Miami Beach fair features 269 exhibiting galleries. Nearly two dozen satellite fairs have also sprouted around Miami. Add in pop-up shows, celebrity-studded product rollouts, as well as Miami’s own galleries and museums all putting on their best faces, and you have the circus that local boosters have taken to calling “Miami Art Week.”

Two dozen satellite fairs, seriously?

Some, like Prizm and Pinta, focus on art made by the African diaspora and Latin Americans, respectively. NADA, or New Art Dealers Alliance, remains the fair on many itineraries for its emphasis on scrappy but influential galleries hovering just beyond Basel’s gatekeepers (and hoping to eventually breach the gate). The works here often offer an early look at tomorrow’s art stars. Another strong contender for Art Basel Jr. is the Untitled fair, whose galleries’ offerings tend to be a bit more thoughtfully gestated than much of NADA’s throw-it-all-against-the-wall-and-see-what-sticks aesthetic.

What about Miami’s own artists?

A perennial sore point for local residents is the dearth of homegrown talent found within the Basel fair — only 3 of its 269 exhibiting galleries are based in Miami. Still, those three are exhibiting some stellar natives: David Castillo will feature the winningly playful assemblages of Pepe Mar; Central Fine is showing paintings by Tomm El-Saieh, whose hypnotic brushwork fuses Haitian folkloric traditions with classic Abstract Expressionism; while Fredric Snitzer’s booth is devoted to paintings by Hernan Bas, whose beguiling, homoerotically charged portraits of dandies and waifs remain some of the strongest work to emerge from Miami over the past two decades.

Where can I see more local galleries?

Head to the Little Haiti neighborhood, the new ground zero for Miami’s most consistently impressive galleries — many of which were priced out of Wynwood as it morphed into an entertainment enclave. Start with Emerson Dorsch and their Color Field-steeped paintings by Mette Tommerup — but call ahead for performance times when Tommerup and her crew will be wrapping themselves inside her huge canvases and rollicking around the room. The Iris PhotoCollective ArtSpace is nearby, dedicated to socially engaged photography and run by Carl Juste, a Miami Herald photojournalist whose work never fails to dazzle. Nina Johnson is featuring new drawings by Terry Allen, and while his Lubbock, Texas, origins are anything but tropical, a rare opportunity to see his handiwork (and hopefully hear him perform some of his delectably barbed country songs) is too good to miss.

What other neighborhoods should I visit for art?

Southwest of Little Haiti, in Allapattah, is Spinello Projects’ group show featuring Clara Varas, who begins her process with an abstract painting (often done on a bedsheet) and then adds all manner of found detritus from the city streets, amounting to sculptural Frankensteins that are fascinatingly more than the sum of their parts. Then head up to the Design District’s Paradise Plaza for the latest jab at the art scene by the Brooklyn artist Eric Doeringer, who first grabbed attention in Miami by creating “bootleg” Art Basel V.I.P. cards (which let more than a few plebeians cross the velvet ropes). He’s since graduated to “bootleg” paintings, and his latest show features handcrafted Christopher Wool knockoffs priced at $1,000 each, several zeros cheaper than the real ones. It’s a stunt that works on both a conceptual level, wryly commenting on a blue-chip artist whose paintings already seem factory-made, and on a pleasurable one, offering Wool fans on a budget a chance to take home a tactile tribute: They may be fake Wools, but they’re genuine Doeringers.

How about Miami’s museums?

Another year, another mogul making a splash with a new privately owned museum. This time it’s Allapattah’s El Espacio 23, exhibiting the contemporary collection of the real estate developer Jorge Pérez, whose name already graces the side of the partially taxpayer-funded Pérez Art Museum Miami. After concerns that Mr. Pérez would turn his attention to his new project — leaving taxpayers to make up the difference — he has publicly assured his namesake museum that it will not see any lessening of his financial support. Over on South Beach, two small institutions have consistently been punching above their weight: The Jewish Museum of Florida-FIU, which is featuring provocative photographs by Zachary Balber that blend Yiddishkeit with thug life, and The Wolfsonian-FIU, paying an 80th birthday tribute to its Willy Wonka-esque founder, Mitchell Wolfson Jr., who has spent a lifetime traveling the world hunting down remarkable historical curios.

Enough museum-hopping, I need a break.

There’s a reason it’s called Miami Beach. Just a few blocks east of the Basel hubbub, the gently rolling surf of the Atlantic Ocean beckons. Bring a towel, stake out a quiet spot on the white sand, and explore the fine art of doing nothing. Admission is absolutely free.

Rubell Museum

1100 NW 23 Street, Miami, (305) 573-6090, [email protected]

Sahred From Source link Travel

from WordPress http://bit.ly/34zuA9G

via IFTTT

0 notes