#feminist polemic

Text

The 2023 Barbie film is a commercial. I’m sure it will be fun, funny, delightful, and engaging. I will watch it, and I’ll probably even dress up to go to the theater. Barbie is also a film made by Mattel using their intellectual property to promote their brand. Not only is there no large public criticism of this reality, there seems to be no spoken awareness of it at all. I’m sure most people know that Barbie is a brand, and most people are smart enough to know this and enjoy the film without immediately driving to Target to buy a new Barbie doll. After all, advertising is everywhere, and in our media landscape of dubiously disclosed User Generated Content and advertorials, at least Barbie is transparently related to its creator. But to passively accept this reality is to celebrate not women or icons or auteurs, but corporations and the idea of advertising itself. Public discourse around Barbie does not re-contextualize the toy or the brand, but in fact serves the actual, higher purpose of Barbie™: to teach us to love branding, marketing, and being consumers.

[...] The casting of Gerwig’s Barbie film shows that anyone can be a Barbie regardless of size, race, age, sexuality. Barbie is framed as universal, as accessible; after all, a Barbie doll is an inexpensive purchase and Barbiehood is a mindset. Gerwig’s Barbie is a film for adults, not children (as evidenced by its PG-13 rating, Kubrick references, and soundtrack), and yet it manages to achieve the same goals as its source material: developing brand loyalty to Barbie™ and reinforcing consumerism-as-identity as a modern and necessarily empowering phenomenon. Take, for example, “Barbiecore,” an 80s-inspired trend whose aesthetic includes not only hot pink but the idea of shopping itself. This is not Marx’s theory on spending money for enjoyment, nor can it even be critically described as commodity fetishism, because the objects themselves bear less semiotic value compared to the act of consumption and the identity of “consumer.”

[...] Part of the brilliance of the Barbie brand is its emphasis on having fun; critiquing Barbie’s feminism is seen as a dated, 90s position and the critic as deserving of a dated, 90s epithet: feminist killjoy. It’s just a movie! It’s just a toy! Life is so exhausting, can’t we just have fun? I’ve written extensively about how “feeling good” is not an apolitical experience and how the most mundane pop culture deserves the most scrutiny, so I won’t reiterate it here. But it is genuinely concerning to see not only the celebration of objects and consumer goods, but the friendly embrace of corporations themselves and the concept of intellectual property, marketing, and advertising. Are we so culturally starved that insurance commercials are the things that satiate our artistic needs?

— Charlie Squire, “Mattel, Malibu Stacy, and the Dialectics of the Barbie Polemic.” evil female (Substack), 2023.

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

April 12, 2019, Updated at 12:22 a.m. ET on April 15, 2019.

In the end, the man who reportedly smeared feces on the walls of his lodgings, mistreated his kitten, and variously blamed the ills of the world on feminists and bespectacled Jewish writers was pulled from the Ecuadorian embassy looking every inch like a powdered-sugar Saddam Hussein plucked straight from his spider hole. The only camera crew to record this pivotal event belonged to Ruptly, a Berlin-based streaming-online-video service, which is a wholly owned subsidiary of RT, the Russian government’s English-language news channel and the former distributor of Julian Assange’s short-lived chat show.

RT’s tagline is “Question more,” and indeed, one might inquire how it came to pass that the spin-off of a Kremlin propaganda organ and now registered foreign agent in the United States first arrived on the scene. Its camera recorded a team of London’s Metropolitan Police dragging Assange from his Knightsbridge cupboard as he burbled about resistance and toted a worn copy of Gore Vidal’s History of the National Security State.

Vidal had the American national-security establishment in mind when he narrated that polemic, although I doubt even he would have contrived to portray the CIA as being in league with a Latin American socialist named for the founder of the Bolshevik Party. Ecuador’s President Lenín Moreno announced Thursday that he had taken the singular decision to expel his country’s long-term foreign guest and revoke his asylum owing to Assange’s “discourteous and aggressive behavior.”

According to Interior Minister María Paula Romo, this evidently exceeded redecorating the embassy with excrement—alas, we still don’t know whether it was Assange’s or someone else’s—refusing to bathe, and welcoming all manner of international riffraff to visit him. It also involved interfering in the “internal political matters in Ecuador,” as Romo told reporters in Quito. Assange and his organization, WikiLeaks, Romo said, have maintained ties to two Russian hackers living in Ecuador who worked with one of the country’s former foreign ministers, Ricardo Patiño, to destabilize the Moreno administration.

We don’t yet know whether Romo’s allegation is true (Patiño denied it) or simply a pretext for booting a nuisance from state property. But Assange’s ties to Russian hackers and Russian intelligence organs are now beyond dispute.

Special Counsel Robert Mueller’s indictment of 12 cyberoperatives for Russia’s Main Intelligence Directorate for the General Staff (GRU) suggests that Assange was, at best, an unwitting accomplice to the GRU’s campaign to sway the U.S. presidential election in 2016, and allegedly even solicited the stolen Democratic correspondence from Russia’s military intelligence agency, which was masquerading as Guccifer 2.0. Assange repeatedly and viciously trafficked, on Twitter and on Fox News, in the thoroughly debunked claim that the correspondence might have been passed to him by the DNC staffer Seth Rich, who, Assange darkly suggested, was subsequently murdered by the Clintonistas as revenge for the presumed betrayal.

Mike Pompeo, then CIA director and, as an official in Donald Trump’s Cabinet, an indirect beneficiary of Assange’s meddling in American democracy, went so far as to describe WikiLeaks as a “non-state hostile intelligence service often abetted by state actors like Russia.” For those likening the outfit to legitimate news organizations, I’d submit that this is a shade more severe a description, especially coming from America’s former spymaster, than anything Trump has ever grumbled about The New York Times or The Washington Post.

Russian diplomats had concocted a plot, as recently as late 2017, to exfiltrate Assange from the Ecuadorian embassy, according to The Guardian. “Four separate sources said the Kremlin was willing to offer support for the plan—including the possibility of allowing Assange to travel to Russia and live there. One of them said that an unidentified Russian businessman served as an intermediary in these discussions.” The plan was scuttled only because it was deemed too dangerous.

In 2015, Focus Ecuador reported that Assange had aroused suspicion among Ecuador’s own intelligence service, SENAIN, which spied on him in the embassy in a years-long operation. “In some instances, [Assange] requested that he be able to choose his own Security Service inside the embassy, even proposing the use of operators of Russian nationality,” the Ecuadorian journal noted, adding that SENAIN looked on such a proposal with something less than unmixed delight.

All of which is to say that Ecuador had ample reasons of its own to show Assange the door and was well within its sovereign rights to do so. He first sought refuge in the embassy after he jumped bail more than seven years ago to evade extradition to Sweden on sexual-assault charges brought by two women. Swedish prosecutors suspended their investigation in 2017 into the most serious allegation of rape because they’d spent five years trying but failing to gain access to their suspect to question him. (That might now change, and so the lawyer for that claimant has filed to reopen the case.) But the British charges remained on the books throughout.

The Times of London leader writer Oliver Kamm has noted that quite apart from being a “victim of a suspension of due process,” Assange is “a fugitive from it.” Yet to hear many febrile commentators tell it, his extradition was simply a matter of one sinister prime minister cackling down the phone to another, with the CIA nodding approvingly in the background, as an international plot unfurled to silence a courageous speaker of truth to power. Worse than that, Assange and his ever-dwindling claque of apologists spent years in the pre-#MeToo era suggesting, without evidence, that the women who accused him of being a sex pest were actually American agents in disguise, and that Britain was simply doing its duty as a hireling of the American empire in staking out his diplomatic digs with a net.

As it happens, a rather lengthy series of U.K. court cases and Assange appeals, leading all the way up to the Supreme Court, determined Assange’s status in Britain.

The New Statesman’s legal correspondent, David Allen Green, expended quite a lot of energy back in 2012 swatting down every unfounded assertion and conspiracy theory for why Assange could not stand before his accusers in Scandinavia without being instantly rendered to Guantanamo Bay. Ironically, as Green noted, going to Stockholm would make it harder for Assange to be sent on to Washington because “any extradition from Sweden … would require the consent of both Sweden and the United Kingdom” instead of just the latter country. Nevertheless, Assange ran and hid and self-pityingly professed himself a “political prisoner.”

Everything about this Bakunin of bullshit and his self-constructed plight has belonged to the theater of the absurd. I suppose it’s only fair that absurdity dominates the discussion now about a newly unsealed U.S. indictment of Assange. According to Britain’s Home Office, the Metropolitan Police arrested Assange for skipping bail, and then, when he arrived at the police station, he was further arrested “in relation to a provisional extradition request from the United States.”

The operative word here is provisional, because that request has yet to be wrung through the same domestic legal protocols as Sweden’s. Assange will have all the same rights he was accorded when he tried to beat his first extradition rap in 2010. At Assange’s hearing, the judge dismissed his claims of persecution by calling him “a narcissist who cannot get beyond his own selfish interests.” Neither can his supporters.

A “dark moment for press freedom,” tweeted the NSA whistle-blower Edward Snowden from his security in press-friendly Moscow. “It’s the criminalization of journalism by the Trump Justice Department and the gravest threat to press freedom, by far, under the Trump presidency,” intoned The Intercept’s founding editor Glenn Greenwald who, like Assange, has had that rare historical distinction of having once corresponded with the GRU for an exclusive.

These people make it seem as if Assange is being sought by the Eastern District of Virginia for publishing American state secrets rather than for allegedly conniving to steal them.

The indictment makes intelligible why a grand jury has charged him. Beginning in January 2010, Chelsea Manning began passing to WikiLeaks (and Assange personally) classified documents obtained from U.S. government servers. These included files on the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq and U.S. State Department cables. But Manning grew hesitant to pilfer more documents.*

At this point, Assange allegedly morphed from being a recipient and publisher of classified documents into an agent of their illicit retrieval. “On or about March 8, 2010, Assange agreed to assist [Chelsea] Manning in cracking a password stored on United States Department of Defense computers connected to the Secret Internet Protocol Networks, a United States government network used for classified documents and communications,” according to the indictment.

Assange allegedly attempted to help Manning do this using a username that was not hers in an effort to cover her virtual tracks. In other words, the U.S. accuses him of instructing her to hack the Pentagon, and offering to help. This is not an undertaking any working journalist should attempt without knowing that the immediate consequence will be the loss of his job, his reputation, and his freedom at the hands of the FBI.

I might further direct you to Assange’s own unique brand of journalism, when he could still be said to be practicing it. Releasing U.S. diplomatic communiqués that named foreigners living in conflict zones or authoritarian states and liaising with American officials was always going to require thorough vetting and redaction, lest those foreigners be put in harm’s way. Assange did not care—he wanted their names published, according to Luke Harding and David Leigh in WikiLeaks: Inside Julian Assange’s War on Secrecy. As they recount the story, when Guardian journalists working with WikiLeaks to disseminate its tranche of U.S. secrets tried to explain to Assange why it was morally reprehensible to publish the names of Afghans working with American troops, Assange replied: “Well, they’re informants. So, if they get killed, they’ve got it coming to them. They deserve it.” (Assange denied the account; the names, in the end, were not published in The Guardian, although some were by WikiLeaks in its own dump of the files.)**

James Ball, a former staffer at WikiLeaks—who argues against Assange’s indictment in these pages—has also remarked on Assange’s curious relationship with a notorious Holocaust denier named Israel Shamir:

Shamir has a years-long friendship with Assange, and was privy to the contents of tens of thousands of US diplomatic cables months before WikiLeaks made public the full cache. Such was Shamir’s controversial nature that Assange introduced him to WikiLeaks staffers under a false name. Known for views held by many to be antisemitic, Shamir aroused the suspicion of several WikiLeaks staffers—myself included—when he asked for access to all cable material concerning ‘the Jews,’ a request which was refused.

Shamir soon turned up in Moscow where, according to the Russian newspaper Kommersant, he was offering to write articles based on these cables for $10,000 a pop. Then he traveled to Minsk, where he reportedly handed over a cache of unredacted cables on Belarus to functionaries for Alexander Lukashenko’s dictatorship, whose dissident-torturing secret police is still conveniently known as the KGB.

Fish and guests might begin to stink after three days, but Assange has reeked from long before he stepped foot in his hideaway cubby across from Harrods. He has put innocent people’s lives in danger; he has defamed and tormented a poor family whose son was murdered; he has seemingly colluded with foreign regimes not simply to out American crimes but to help them carry off their own; and he otherwise made that honorable word transparency in as much of a need of delousing as he is.

Yet none of these vices has landed him in the dock. If he is innocent of hacking U.S. government systems—or can offer a valid public-interest defense for the hacking—then let him have his day in court, first in Britain and then in America. But don’t continue to fall for his phony pleas for sympathy, his megalomania, and his promiscuity with the facts. Julian Assange got what he deserved.

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

god barbie was so bad. was too busy being clever and referential and ironic and delivering bad liberal feminist polemics to actually bother being a good movie. fucked pacing, inconsistent tone, too many themes done badly, not enough texture. didn't know if it wanted to be a kids movie or a mattel advert or pinocchio for adults conversant in the culture war. possibly the nadir of greta gerwig's career.

58 notes

·

View notes

Text

The evaluation of Mayo's work [Mother India] and its impact has been left to such scholars as the authors of Marriage: East and West, who write:

The dust finally settled. It was conceded that Katherine Mayo's facts, as facts, were substantially accurate. It was recognized that she had taken up a serious issue and drawn attention to it, which had helped in some measure to hasten much-needed reforms. But at the same time her book had done a grave injustice to India, in presenting a one-sided and distorted picture of an aspect of Indian life that could only be properly understood within the context of the entire culture [emphases mine].

Thus Mayo is put in her place. We find here the familiar use of the passive voice, which leaves unstated just who conceded, who recognized. We find also the familiar balancing act of scholars, which gives a show of "justice" to their treatment of the attacked author. The qualifying expression, "as facts," added to "facts," has the effect of managing to minimize the factual. Women who counter the patriarchal reality are often accused of "merely imagining," or being on the level of "mere polemic." Here we have "mere" facts. Then the authors graciously concede that Mayo hastened "much-needed reforms," which gives the impression that everything has now been taken care of, that the messy details have been tidied up. Then comes the peculiarly deceptive and unjust expression "grave injustice to India." Mayo was concerned about grave injustice to living beings, women. Injustice is done to individual living beings. One must ask how it is possible to do injustice to a social construct, for example, India, by exposing its atrocities. We might ask such re-searchers whether they would be inclined to accuse critics of the Nazi death camps of "injustice" to Germany, or whether they would describe writers exposing the history of slavery and racism in America as guilty of "injustice" to the United States. The Maces go on to accuse Mayo of distorting "an aspect of Indian life." But what is "Indian life"? Mayo is concerned not with defending this vague abstraction (presumably meaning customs, beliefs, social arrangements, et cetera), but with the lives of millions of women who happened to live in that part of patriarchy called "India."

The final absurdity in this scholarly obituary is the expression "properly understood within the context of the entire culture." It is Katherine Mayo who demonstrates an understanding of the cultural context, that is, the entire culture, refusing to reduce women to "an aspect." Her critics, twenty years after her death, attempted to absorb the realities she exposed into a "broad vision," which turns out to be a meaningless abstraction.

Feminist Searchers should be aware of this device, commonly repeated in the re-searchers' rituals. It involves intimidation by accusations of "one-sidedness," so that others will not listen to the discredited Searcher-Scholar who refused to follow the "right" rites. The device relies upon fears of criticizing "another culture," so that the feminist is open to accusations of imperialism, nationalism, racism, capitalism, or any other "-ism" that can pose as broader and more important than gynocidal patriarchy. Thus the just accuser becomes unjustly sentenced to erasure. Her life's meaning, as expressed in her life's work, is belittled, reversed, wiped out.

Feminist Seekers/Spinsters should search out and claim such sisters as Katherine Mayo. Her books are already rare and difficult to find. It is important that they do not become extinct. Spinsters must unsnarl phallocratic "scholarship" and also find our sister weavers/dis-coverers whose work is being maligned, belittled, erased, deliberately forgotten. We must learn to name our true sisters, and to save their work so that it may be continued rather than re-covered, re-searched, and re-done on the endless wheel of re-acting to the Atrocious Lie which is phallocracy. In this dis-covering and spinning we expand the dimensions of feminist time/space.

-Mary Daly, Gyn/Ecology

#mary daly#Katherine mayo#patriarchal scholarship#radical feminist analysis#female oppression#patriarchy#suttee

9 notes

·

View notes

Note

wait what medium piece has been circulating? (also ty for the new yorker link i love alex barasch's work)

it's ok i thought it was right to point out the market expansion mattel is gaining with this film but i disagreed with some of the framing of previous feminist waves and i found the new yorker piece more helpful because it placed the film in context of mattel's other studio moves and the larger trend in hollywood toward pre-existing ip. also i generally like barasch's writing as well ^_^

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

I dunno maybe the reaction of "well of course the 4B movement hates trans women specifically" isn't really the most effective way of promoting an understanding of transmisogyny that is decoupled from "hating men" or misandry as it's origin, and actually I do think that there are very basic things that are important to sort out before I would write barely informed people who sympathize with the 4B movement or more general radical feminist ideas completely off.

Because it's worth talking about that the stuff the articles and general discussions on the 4B movement lead with isn't biology or definitions of what a woman is, it's the four no's that relate to not being in a relationship/marriage with a man and not having/raising kids and if you read that there seem to be like a nontrivial amount of steps involved in getting from just being against marriage to a movement where people say stuff like "already the male toddler routinely commits acts of sexual violence" and a lot people like to fill in these steps with just blind hatred for men - which may or may not be true in an individual case - but ignores the broader picture and the basic point of contention between trans exclusive radical feminism and transfeminism, a point that has nothing to do with hating men or not hating men.

So first off I don't actually know much about the different kinds of radical feminism and transfeminism because honestly I don't really have the stomach to really get into all that anymore and so this is more like a polemic about some very rough basics instead of like theory or whatever.

Uhh yeah so I think an opposition to marriage is a very reasonable stance. We can talk all about the implications of projecting economic and social relations of an entire society on individual behaviours later. But to start with it shouldn't be controversial to say that marriage as an institution is all about regulating women according to patriarchal ideals, and not just socially but even legally. In germany, which I'm using as an example because that's where I am, it was only in 1976 (so at that point I'm talking abt west germany obvsly) that the marriage law was reformed in such a way that a married woman was legally allowed to work. Before that married women were only allowed to earn money if it was, as wikipedia (yeah ik ik) puts it, "compatible with her duties in marriage and family" which is very euphemistically called das Leitbild der Hausfrauenehe fucking hell. 1976. But even if it is not or was not encoded in law like that, the ideal of what family means in any patriarchal society is about confining women to domestic labour to some degree. When covid lockdowns hit, it were, in heterosexual partnerships, disproportionately women that cut back on their working hours (and probably free time but the reports I have seen only focus on work) to care for children. That doesn't come out of nowhere, and even though luckily for us not every place in the worls is (west) germany, it doesn't seem unreasonable to hear about a movement that loudly rejects marriage, refuse to inform yourself further about particulars, and go "sure that sounds great to me". Because maybe I did that for two seconds before my evil brain added "I bet they only have great things to say about trans women/ppl like me/who want to be women/y'know whomst I am talking of".

Anyway, it's part of a longstanding, western, medical discourse, that really took off from like the 18th century onwards (don't quote me on that) to justify patriarchal societal structure with the Biology of the fEMaLe bODy. What it all comes down to is that, when a patriarchal society says something like: "It is because of women's bodies that they ought to stay in the kitchen" or some variation thereof, radical feminism has two answers to that. The first, that you see more often shared on social media because it is very obviously nothing but a sockpuppet for fascism and similar ideologies, goes like this: "It is true that the nature of women's bodies is the reason for women's position in society" as opposed to the wielding of economic power, social stigmatization and/or the threat of brute force.

The second reaction is: "It is not the nature of women's bodies that determines the place of women in society, but it is having a woman's body that makes society chose one as a target of the violence necessary to ensure the stability of patriarchy." Which, in comparison to the first response, seems much more reasonable. Mostly, it doesn't require believing that women are naturally inferior to men. But like the first response it too ignores the roles economical and social power play in society. Because this power is not enacted upon one abstract, idealized female body, it is enacted on actual people. This is what people are talking about when they say that sex/gender is a social construct, or dependend on economic and social organisation. Like in the radical feminist conception there is a flat, simple relationship between the individual and the forces that be: "female body" -> application of patriarchal force. Here the body acts as a criterion for a filter. But even that conception requires a comparison to see if, and in how far, real people agree with an ideal female body. And my point here is not that this ideal body is constructed, but that the entire process of selection and application of force is glossed over: how far can someone's body differ from the ideal "female body" and still make that person be deemed a woman? How exactly does conforming or not conforming to that ideal affect the application of patriarchal force? How does behaviour factor into that? No, really, how? Etc, etc.

I am sure that if one sits down and really tries, one can find answers that still allow one to call me every name one's heart desires, but that's besides the point. What I presented here as the second response of radical feminism is a slight of hand. It puts the machinations of patriarchy aside as a given that does not warrant further investigations, and focuses solely on what the "female body" is and is not - and that despite ostensibly not assuming the patriarchy as natural.

That and not blind hatred of men is how we get from "no dating/marriage/sex/kids" to descriptions of toddlers as rapists and extreme anxiety over the mere existence of trans women. If patriarchal society posits the nature of the body as the justification for the places of women in society then primarily focusing on the body as the vector of oppression causes one to mirror the patriarchal policing of what people's bodies are supposed to be like, and that not outwards but inwards: these movements do not police men's bodies. To refer to the one big article that is going around: the 4B movement is not asking for pictures of adam's apples of men, but only for those of the women that want to attend their events. In trans women circles it's often pointed out how saying that TERFs police women's gender expressions and bodies puts cis women above trans women, like it only matters when it accidentally hits a cis woman, but it is still worth pointing out that *that* is at the core of so called radical feminist practices. That *that* is supposed to be the resistence against patriarchy.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Lisa vs. Malibu Stacy” is a classic Simpsons episode because it is such a clear embodiment of the function of Lisa Simpson. She is positioned as fundamentally, politically correct. She is also positioned as condescending and just plain old annoying, which undermines her correctness. It is the same criticism faced by the Barbie Liberation Organization and the Barbie dissidents of the twentieth century. Part of the brilliance of the Barbie brand is its emphasis on having fun; critiquing Barbie’s feminism is seen as a dated, 90s position and the critic as deserving of a dated, 90s epithet: feminist killjoy. It’s just a movie! It’s just a toy! Life is so exhausting, can’t we just have fun? I’ve written extensively about how “feeling good” is not an apolitical experience and how the most mundane pop culture deserves the most scrutiny, so I won’t reiterate it here. But it is genuinely concerning to see not only the celebration of objects and consumer goods, but the friendly embrace of corporations themselves and the concept of intellectual property, marketing, and advertising. Are we so culturally starved that insurance commercials are the things that satiate our artistic needs?

When we speak about Barbie, it is shockingly easy to recognize her personhood, to describe “who she is.” It is much harder to talk about Barbie in terms of “what it is”—a combination of plastics available for purchase. It is no coincidence that Barbie’s creation coincided with the post-War shift in disposable consumer goods; Barbie’s wide array of career options and outfits meant that Barbies could be collected, traded, and disposed of—a markedly different attitude towards dolls than the expensive porcelain creations of the early 20th century. Barbie is a woman (or at least, an evocation of one), but Barbie™ is a brand. It is probably one of the first brands that children are aware of, one with a long history of corporate tie-ins… the first inter-brand Barbie was simply called “Barbie Loves McDonalds.” By placing Barbie at the center of debates about girlhood and womanhood, we have allowed the brand to maintain its place at the heart of our culture. And as Barbie becomes more inclusive, more friendly, more aspirational, and more abstract, we must also become sharper, more critical, and more grounded about what Barbie is actually selling us. In short, as we find ourselves seated for Gerwig’s film in our hairspray and hot pink outfits, we must become Lisa Simpsons.

-Mattel, Malibu Stacy, and the Dialectics of the Barbie Polemic, by Charlie Squire.

#not at all the point of the article but i was reminded of how much i love lisa simpson lmao#talking to the void#consumerism#capitalism#current issues

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Stand by Your Manhood: A Game-changer for Modern Men

Men are brilliant. Being a man is brilliant. Seriously, it is. Except for penile dysmorphia, circumcision, paying the bill, becoming a weekend father, critics who've been hating on us for, well, pretty much fifty years - oh, and those pesky early deaths. Fortunately, Peter Lloyd is here to tackle the controversial topics in this fearless - and frequently hilarious - bloke bible. Part blistering polemic, part politically incorrect road map for the modern man, Stand By Your Manhood answers the burning questions facing the brotherhood today:

Should we fund the first date?

Are we sexist if we enjoy pornography?

Is penis size a political issue?

And do feminists secretly hate us?

Frank, funny and long overdue, this is the book men everywhere have been waiting for.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

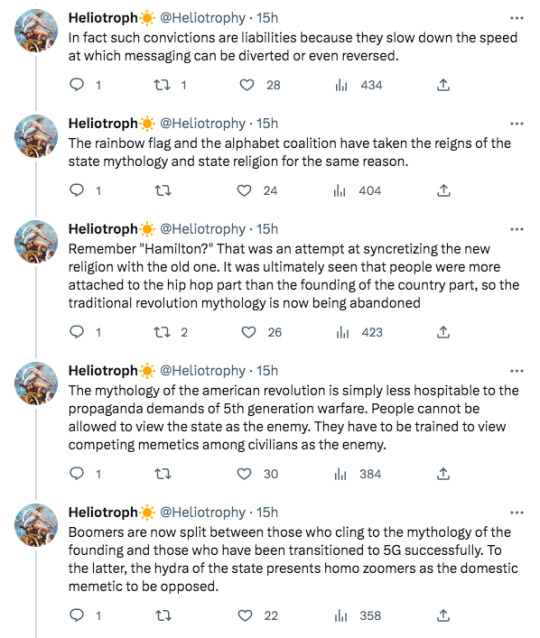

I hope Tumblr can forgive the piquant way these Twitter anons phrase some things, because the above mapping is basically correct, except that the phenomenon mapped is bigger than America's recent generational divides—bigger, in fact, than America. I give you, for example, the peroration of an article by friend-of-the-blog Nancy Armstrong. The article was published in 2001, before social media and when the Zoomers were still in the cradle. Armstrong's polemical target is Richard Rorty, whom she likens to the Victorian English liberals Mill and Arnold, seeing all three as panicked by the encroachment of popular heterogeneity upon the sphere of a unified national culture, whether late-19th-century English culture or late-20th-century American culture. For the purposes of anon's framing, Rorty (b. 1931) is a Boomer and Armstrong (b. 1938) is a Zoomer, but, as you see from the dates, that can't be right. What anon takes to be American Zoomer ideology goes back at least to the first Late Victorians who rebelled against Arnold (Mill/Arnold = Boomers; Pater/Wilde = Zoomers), themselves the distant founders of our queer politics defined by the separation of sign (gender) from referent (body), which, as anon rightly says, have become the power politics of empire today in a world-historical incidence of what I have in a narrower but related circumstance traced as the path "from counterculture to hegemony."

In our present cultural milieu, it is even less practical to believe that the cultural turn can be reversed by detaching politics from culture and restoring the mimetic priorities of old-fashioned realism than to long for the aesthetic autonomy of New Criticism or look for hope in the inspirational works of our literary tradition. To come to this conclusion is to admit that any responsible political action rests on understanding the degree to which the world we inhabit actually depends on the way that we read and represent the things and people in it. Changing an established world picture is an admittedly monumental task that may well begin and end in the literary classroom. But precisely because our Victorian forebears were so successful in establishing their picture of the world as the world itself, the fantasy that one can remake one’s culture through criticism is not only a legacy that they bequeathed to us. That fantasy also offers an effective means of displacing the picture of a world divided into homogeneously populated nations that our Victorian forebears worked so hard to put in place. The crises that arise when that old ideal of the nation is severely challenged do not disrupt or threaten American culture. Our culture is a culture in crisis, and some of us like it that way.

—Nancy Armstrong, "Who's Afraid of the Cultural Turn?" differences: A Journal of Feminist Cultural Studies, 12.1 (2001)

#nancy armstrong#richard rorty#cultural studies#cultural criticism#john stuart mill#matthew arnold#walter pater#oscar wilde#literary theory

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Book 33, 2023

Everyone loves "The Yellow Wallpaper", the semi-autobiographical gothic horror story about postpartum mental health issues and the treatment of women's illness in the late 19th and early 20th century.

We regret to inform you that the author of "The Yellow Wallpaper", a white feminist born in 1860, has horrible politics. Who could have foreseen this?

The answer is: anyone if we studied literature in the context of an author's wider body of work, instead of cherry picking and whittling down an author profile for specific relevance to that chosen work. I studied "The Yellow Wallpaper" in multiple university classes, because it is an excellent little story, heavy with symbolism and material to interpret, while also having a very clear message. It's unsettling, raw, claustrophobic, bumping against issues that we're still grappling with over a hundred years later. There's a reason Charlotte Perkins Gilman is primarily remembered for this story, which doesn't reveal any of her more questionable opinions. So periodically people on social media get to discover things like how she was an eugenicist.

I wrote a number of papers on depictions of single-sex societies in fiction while at school, which means I also read Gilman's novella, "Herland", which gives room for her wider politics to breathe, but I was still surprised by what I found in her fiction reading "Herland and Selected Stories".

For starters: a lot of them are fairly unimpressive and mundane and I wasn't reading a collection of all of Gilman's fiction. These were curated by an editor. I admit to not having read Barbara H. Solomon's introduction; I skimmed it and didn't see any references to Gilman's opinions that are less palpable to modern readers. Perhaps there she explains her logic for the stories she selected.

Some of the stories concern utopia-adjacent feminist ideals relevant to Gilman's time. Older women finding themselves invigorated by late-in-life discovery of things that fulfill them outside the confines of the wife-and-mother role. Young women guided to more fulfilling lives independent of men they don't really want by older mentors. Women finding common ground in being hurt by the same man and uniting with each other, instead of embracing a villain in the Other Woman. Women finding love but with men who respect them and don't ask them to change themselves. Which is all fine and can be recognized as progressive and counter to the culture of the time.

They're not very interesting, though, Gilman's polemic against the patriarchy more significant than any interesting plot or character sketch or artistically pleasing turns of phrase.

The selected stories don't particularly advertise Gilman's racial stances. Gilman was a great-niece of Harriet Beecher Stowe and, while she acknowledged the ill that had been done to Black Americans, similarly fails to understand the wider systemic problems of post-slavery America and her own contributions in perpetuating a culture of white supremacy. There are a few references to "coloured" maids, most egregious in "Her Housekeeper", where a Black maid is present and named and the reader is informed she sleeps on the couch, but doesn't care where she sleeps, if she even needs to sleep. Unsurprisingly, what's most conspicuous is the otherwise complete absence of Black people from any of the selected stories.

The matter of eugenics is more clearly on display, thought, particularly in "Herland", where good women and citizens who are "inferior" recognize themselves as such and choose to forego motherhood (the female ideal in their society and for the women in many of the selected short stories, despite Gilman's beliefs being counter to strict gender roles), preventing the spread of those "inferior" qualities (physical and mental disabilities and asocial tendencies that could lead to crime). The women are all fit and diversely Aryan (blonde, brunette, redheaded, pale, tan). Other stories remind us that fat women are repulsive to witness in society.

The story that really captured my attention was "When I Was A Witch", in which a woman acquires ambiguous magical abilities that she uses to angrily right societal wrongs, only to lose them when she tries to impose something positive and pure in the form of making all women realize all the good power and potential available to them as women, drawing a line between women as they exist and "real" women, who have embraced "... their real power, their real dignity, their real responsibility in the world ...", who don't behave in a way the narrator finds embarrassing. This is labeled white magic versus her previous black magics that come from rage. But it's undeniable that those black magic wishes represent real beliefs of Gilman's, many of them coming from a place of good intentions. Carriage drivers are made to feel the physical suffering their horses endure, reducing their cruelty to the animals. Shareholders of major companies are made to feel the suffering the people at the bottom of the chain of power, pushing them to change their priorities from profits to people. Domestic animals in the city lead lives either stifled or full of suffering, so they all suddenly die. Parrots are given the ability to speak their 'opinions' of their owners and they all hate them.

Also, they think their predominantly female owners are ugly.

Gilman would love PETA.

There's a condescending feminist version of noblesse oblige in how Gilman and her protagonists talk about other women who have not found or chosen the path of what Gilman sees as empowered, fully realized femaleness that leaves a bad taste in my mind. Women need to work together to uplift each other and rely on each other in their stories, but they need to recognize that some women are going to try and keep them from fulfilling themselves because they don't Understand and have become disconnected from True Femaleness in a very second-wave eco-feminist nature mother way.

"The Yellow Wallpaper" is clearly Gilman's most enduring work of fiction because, in addition to being an easy work to teach, it's genuinely good and coming from a real, personal place. It doesn't propose a solution to the protagonist's distress, it has an ending that breaks her instead of giving her a neatly gift-wrapped solution because there isn't an easy solution for post-partum depression. When she moves away from that personal experience in her fiction, the reader also moves away from connecting with it. The politics, both good and bad, don't intersect meaningfully with the personal, and a number of them simply aren't good.

Sometimes it's easy to forget an author might only have one good one in them.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

I was grabbing a drink with an old friend when it happened. I told her I was excited about an upcoming reporting trip to Vancouver, to interview Naomi Klein. My friend wrinkled her nose, as if the bartender had just farted. Then she asked why I’d give my time to someone who thought the Covid-19 pandemic was a conspiracy.

I sighed. Turns out, she’d been thinking of Naomi Wolf.

You know Naomi Klein, right? Rabble-rousing leftist journalist and climate activist? Author of Gen X touchstone No Logo and the mega-influential The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism? Decidedly not the former liberal feminist writer turned far-out Covid truther Naomi Wolf? But just because they share a first name—and, I suppose, are both telegenic Jewish public intellectuals who found fame through polemical writing—people confuse the two Naomis constantly. Klein gets mixed up with Wolf so much, in fact, a Twitter mnemonic was born: “If the Naomi be Klein you’re doing just fine / If the Naomi be Wolf, oh, buddy. Ooooof.”

Thus the basis of Klein’s new book, Doppelganger. Writing hundreds of pages based on the Twitter discourse surrounding your evil twin is, of course, a deeply questionable choice. Klein openly admits that her family and friends questioned her sanity. As she is quick to point out, though, Doppelganger is not really about Wolf. Instead, the book uses the experience as an entry point to dissect the “intellectual and ideological mayhem” of the Covid era. How wellness entrepreneurs demonize medicine. How the far right appropriates and warps leftist talking points. How parents insist on seeing their children as reflections of themselves. In all this, Klein writes, there’s a new doubling going on—weird fun house distortions of what used to be more straightforward realities. It’s a lively, slightly unwieldy, wholly vital work. It could only be hers.

Klein moved to the Sunshine Coast of British Columbia during the pandemic, a riotously beautiful nook of that vast province, where towns are nestled into fjords. It’s a place far more likely to be visited by orcas than members of the US media, and in the interest of saving me a journey on a ferry—you can only get to her home by boat or floatplane—Klein met me at her office at the University of British Columbia, where she codirects the Centre for Climate Justice. We’d intended to stroll around the sprawling, sunny campus, but the conversation kept such an intense clip, we ended up simply sitting for hours.

Kate Knibbs: Doppelganger is much more personal than your previous work. Why?

Naomi Klein: I thought it was really important not to be on the outside of this story, but to be inside, to fess up to my own disorientation. Having a doppelganger who a lot of people confuse me with is a type of losing oneself, and it provided a toehold into this larger and more interesting set of feelings, of being lost in a world we might not recognize.

You listened to conspiratorial podcasts for research, including Steve Bannon’s. Were you ever worried you’d get lost in those worlds?

I felt that way the first time I went to a climate change denial conference. I was a tiny bit worried I would start to doubt my own understanding of the science by listening to them. But the exact opposite happened, because it was so completely incoherent. One guy says it’s getting cooler. Another says it’s getting hotter—but the sunspots! Another guy says everyone should just get air-conditioning. That’s what it’s like listening to Bannon or any of those “intellectual dark web” types. You can see it right now with RFK Jr. He’s saying Covid was a bioweapon. This is also the guy who told people not to wear masks, not to lock down, not to get vaccinated. So which is it? Occasionally Bannon would have someone on who would claim that people were just dropping dead from the vaccine.

Like the whole #DiedSuddenly thing?

Exactly. What you start to realize is that these people are acting as if we were immortal before Covid. As if no one died from anything. What worries me more isn’t that I’m going to start thinking that the vaccines are killing us or anything like that. It’s that I understand why the things he’s doing are so resonant.

Why are they so resonant?

This is Bannon’s gift, sorry to say, and it’s how Trump won in 2016: by identifying a bloc of Democratic voters who had been screwed over by the party because they lost jobs to corporate free trade deals. So the offer was a counterfeit version of the left, which is what right-wing populism does. They were not rewriting trade deals in any significant way that would help workers. They were offering huge gifts to the already wealthy through tax cuts. But when people are desperate enough, they’ll go for a counterfeit.

I have someone close to me who has definitely bought into that counterfeit populism. It’s been hard to watch the change take place.

I’ve had so many conversations with people describing that feeling. It’s like watching Invasion of the Body Snatchers.

But I suppose we all have many competing, constantly mutating versions of ourselves. How do you think about your public persona now?

When we think about performing ourselves, we think about social media. For me, that’s Twitter [since renamed X]. And right now I don’t think any of us feel in control of whatever the fuck is happening on Twitter. But we’re still there, hoping to recapture something. I hope my relationship to my public persona is like my relationship with Twitter. I’m not really trying anymore.

Do you think there’s a way for you to have a conversation like this that’s truly authentic, or are you in some sense creating a doppelganger version of yourself to promote the book?

There’s always going to be some contradictions involved in hawking a book when you’re an anti-capitalist author. I’ve been living with that contradiction for a long time. I find talking to people exciting. I have ideas that I wouldn’t have had otherwise. I had the idea to write No Logo while I was doing an interview with a student journalist.

Are your students influential in other ways?

One of the really nice things about being on campuses right now is that, if I was just getting my sense of youth culture through media, I’d think that all young people are constantly posing and performing themselves on Instagram. But it’s definitely a minority. A lot of young people feel alienated from it.

I get a lot of youth culture tidbits from my babysitter, which is how I know that super polished and posed Instagram photos are seen as a geriatric millennial thing.

They want it to look really authentic, to be messy.

I reread No Logo recently. It holds up.

Maybe not the Blockbuster references!

Honestly, we need to bring back your concept of selling out. I got in a lot of trouble on Twitter a few months ago for saying the Barbie movie looked bad. I love Greta Gerwig, but I don’t want to like Barbie! I hate the idea of a Mattel Cinematic Universe.

The thing that’s so clever is that it’s shiny and pretty enough to get the normie Barbie fans, but it also has so-called subversive content for the people who don’t want to like Barbie. It’s genius marketing. But the world is fraying. It’s an odd time for us to get excited about pink plastic.

Probably an odd time for me to be really annoyed about it, too.

No, I think it’s time to have some standards again.

Do you ever think about returning to that mode of criticism?

Just to keep you company?

To keep me company, and because efforts to turn cinema and television into capital-B Brands—the Marvel Cinematic Universe, most infamously—are so much more flagrant than before.

And also to keep us in our childhoods in a strange way. This is not kid content, it’s adult content, but it’s feeding on nostalgia for being 8 years old.

What’s a recent movie you liked?

Despite the critics hating it, I thought Don’t Look Up was brilliant. It was taking aim at the culture of narcissism and distraction at this most critical moment. It was broad, like all of Adam McKay’s comedies. But that was not the problem. The problem was that it was right.

Doesn’t everyone die at the end?

That’s the best part. He fucked with the Judeo-Christian trope that the righteous will be saved.

I do think it was broad.

Well, Anchorman is broad!

True. But I don’t necessarily want my comedy to be didactic. I just really don’t want it to be branded content from Mattel. There’s this amazing Canadian filmmaker, Sarah Polley, and she’s doing a live-action Bambi.

My grandpa worked on the original Bambi. He was an animator.

I read about this. Didn’t he get fired for trying to unionize?

He did. And they had the first strike at Disney during the production of Dumbo.

Have you been paying attention to the strike wave happening?

It’s exciting. I’m really glad that there’s the focus on AI.

What else interests you politically, right now?

I think it’s important to think about where the Covid denialism energy is going now that there aren’t vaccine mandates. It’s morphing, going in new directions, and it’s important to try and follow that.

Which new directions?

There are two main wellsprings the Covid denialism movement drew from. One was the anti-vax people. The other group was climate deniers. Now, when you post anything about climate change, you’ll get hit with “Davos elites, Great Reset.”

When we were talking earlier about how people take leftist ideas and make counterfeit versions of them, I was thinking about how that happened to the shock doctrine—your idea that global elites use disasters to push brutal policies to benefit themselves at the expense of the masses. People co-opted the concept to talk about the Great Reset, saying there was a global conspiracy to use Covid to strip away personal freedoms. Has this changed your relationship to your own ideas? Do you feel less ownership over them?

I’ve never felt I had that much control over my ideas in the culture. I remember Arundhati Roy saying to me many years ago, we can’t control what our words do once we release them. I have tried to correct the record and do my own writing about what I think the shock doctrine is and isn’t, but I think I’ve always felt a bit of detachment around it.

Jane Fonda started her Fire Drill Fridays because of you.

That was just getting somebody at the right moment of receptivity. That’s what Jane did. I take no credit.

Do you believe in the horseshoe theory? Are the people on the far left swinging far right because they’re attracted to conspiratorial thinking about Covid?

There are some people who have decided that Tucker Carlson is a great guy and Trump’s better than Biden. But most of those people I wouldn’t consider very left-wing. Someone like Glenn Greenwald. For a while, he seemed to be a left-wing person because he was against the Patriot Act and the Iraq War. But he was a libertarian upset about Bush-era government overreach. So it makes sense, when a government has to robustly respond to a pandemic, that a lot of those people got upset. I know some of these people—Matt Taibbi and Glenn Greenwald—I know that they are not deep left thinkers. We have to make the distinction.

Do you think there’s an incentive to shift rightward now to bolster one’s personal brand online?

Yes.

Could there be a positive incentive the other way? Is it possible to build up an ecosystem of independent leftist outlets?

Remember that idea? We need to invest in media, and not be reliant on quixotic billionaires to find one another. I think we need to get serious about independent alternative media and local media.

Meaning, like, a new Twitter?

The problem with something like Mastodon or the smaller Twitter competitors is that they’re not able to offer what Twitter did at its best, which was this feeling of we’re all having one conversation together.

I don’t know if there will ever be one main conversation again.

I wish Twitter could’ve been turned into a co-op. This is labor we’ve put into this thing. We all wrote for free!

A lot.

There was always something self-exploiting about that. Sure, we were able to share our articles and do self-promotion, but I always knew they were going to try to charge us. It’s too valuable.

There’s a co-op movement for media startups, where the writers own their outlets, but I haven’t seen the same thing happen for social media.

And the thing happening now with AI—it was one thing for all of us to be writing for free for Zuckerberg and Musk, but now it turns out that all of that content is being used to create doppelgangers of us by AI companies. Now that’s going to be used to put people out of work, or cheapen their labor.

It’s accelerating so rapidly. Big outlets are already putting out AI-generated articles.

This relates back to conspiracies and why they’re spreading as quickly as they are. It’s a dangerous time to give people more reasons not to believe what’s in front of them. Anything you’re shown now can be dismissed as fake news. “It’s not even Biden, it’s AI.” We’re barely glimpsing the ramifications.

In Doppelganger, you wrote about a South Korean politician who used AI to look younger.

The thing about the Korean example is, it was not hidden. Everyone knew. And it worked for him. So who knows? As our candidates get older, they may rely on AI doppelgangers. It’s being packaged as a way to reach younger voters, because they prefer synthetic reality.

Have you had discussions with your students about AI? Do they actually prefer synthetic reality?

Last semester, ChatGPT was really everywhere, and we were discussing how they were not using it to write their essays. I think we’ve overfocused on the plagiarism piece of things. It’s just one element within a completely unstable and frightening future. Maybe it’s helpful writing essays, but they also know it’s replacing entire sectors they may have been preparing for—between not being able to afford living in the city to the acceleration of the climate crisis to AI changing the job market.

I’m aware of at least one podcasting company hoping to use AI to translate podcasts into a bunch of different languages. It sounds cool, but then you think: What about translators?

The thing I find disingenuous is when you hear, oh, we’re going to have so much leisure time, the AI will do the grunt work. What world are you living in? That’s not what happens. Fewer people will get hired. And I don’t think this is a fight between humans and machines; that’s bad framing. It’s a fight between conglomerates that have been poisoning our information ecology and mining our data. We thought it was just about tracking us to sell us things, to better train their algorithms to recommend music. It turns out we’re creating a whole doppelganger world.

We’ve provided just enough raw material.

When Shoshana Zuboff wrote The Age of Surveillance Capitalism, it was more about convincing people who’d never had a sense that they had a right to privacy—because they’d grown up with the all-seeing eye of social media—that they did have a right to privacy. Now it’s not just that, even though privacy is important. It’s about whether anything we create is going to be weaponized against us and used to replace us—a phrase that unfortunately has different connotations right now.

Take it back! The right stole “shock doctrine,” you can nab “replace us” for the AI age.

These companies knew that our data was valuable, but I don’t even think they knew exactly what they were going to do with it beyond sell it to advertisers or other third parties. We’re through the first phase now, though. Our data is being used to train the machines.

Fodder for a Doppelganger sequel.

And about what it means for our ability to think new thoughts. The idea that everything is a remix, a mimicry—it relates to what you were talking about, the various Marvel and Mattel universes. The extent to which our culture is already formulaic and mechanistic is the extent to which it’s replaceable by AI. The more predictable we are, the easier it is to mimic. I find something unbearably sad about the idea that culture is becoming a hall of mirrors, where all we see is our own reflections back.

You reached out to Naomi Wolf and she didn’t respond. If she had responded, would you want to debate her?

I think it’s important to engage with what’s being said and marshal counterfacts. But the idea of just sneering at people is dangerous. I think we do need to debate, but whether that means creating some kind of theatrical Naomi vs. Naomi spectacle—I don’t know about that.

You could be second billing to Musk vs. Zuckerberg.

Anyway, as you know from reading the book, it’s not really about her. She’s just a case study. I follow her down the rabbit hole. But I’m more interested in the rabbit hole.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

The universal and irrational belief that there is a "base element" in femaleness reflects "man's underlying fear and dread of women" to which Karen Horney referred, pointing out that it is remarkable that so little attention is paid to this phenomenon. More and more evidence of this fear, dread, and loathing is being unearthed by feminist scholars every day, revealing a universal misogynism which, in all major cultures in recorded patriarchal history, has permeated the thought of seemingly "rational" and civilized "great men"—"saints," philosphers, poets, doctors, scientists, statesmen, sociologists, revolutionaries, novelists. A quasi-infinite catalog could be compiled of quotes from the male leaders of "civilization" revealing this universal dread—expressed sometimes as loathing, sometimes as belittling ridicule, sometimes as patronizing contempt.

What has not received enough attention, however, is the silence about women's history. I do not refer primarily to the "Great Silence" concerning the acts of women under patriarchy, the failure to record or even to acknowledge the creative activity of great women and talented women. However, this is extremely significant and should be attended to. A typical case was Thomas More's brilliant daughter, Margaret. Men simply refused to believe that she was the author of her own writings. It was supposed that certainly she could not have done it without the help of a man. There were the women authors (e.g., George Eliot, George Sand, the Brontës) who could only get acceptance for their writings by disguising their sex under the pen name of a man. A reasonably talented woman today need only reflect honestly upon her own personal history in order to understand how the dynamics of wiping women out of history operate. Women who give cogent arguments concerning the oppression of women before male audiences repeatedly hear reports that "they were not able to defend their position." Words such as "flip," "slick," or "polemic" are used to describe carefully researched feminist writings. I point to this phenomenon of the wiping out of women's contributions within the context of patriarchal history, because it means that we must consciously develop a new sense of pride and confidence, with full knowledge of these mechanisms and of the fact that we cannot believe the history books that tell us implicitly that women are nothing. I point to it also because we have to overcome the hyper-cautiousness (not to be confused with striving for accuracy) that keeps us from strongly afirming our own history and thereby re-creating history.

I refer to the silence about women's historical existence since the dawn of patriarchy also because this opens the way to overcoming another "Great Silence," that is, concerning the increasing indications that there was a universally matriarchal world which prevailed before the descent into hierarchical dominion by males. Having experienced the obliterating process in our own histories and having come to recognize its dynamics within patriarchal history (which is pseudo-history to the degree that it has failed to acknowledge women), we have a basis for suspecting that the same dynamics operate to belittle and wipe out arguments for and evidence of the matriarchal period. Erich Fromm wrote:

The violence of the antagonism against the theory of matriarchy arouses the suspicion that it is . . . based on an emotional prejudice against an assumption so foreign to the thinking and feeling of our patriarchal culture.

While of itself such violence of antagonism obviously does not prove that the position so despised is correct, the very force of the attacks should arouse suspicions about the source of the opposition. It is important not to become super-cautious and hesitant in looking at the evidence offered for ancient matriarchy. It is essential to be aware that we have been conditioned to fear proposing any theory that supports feminism.

The writings supporting the matriarchal theory produced many decades ago are receiving new attention. These early contributions included the works of Bachofen (Das Mutterrecht, 1861), Louis Henry Morgan (Ancient Society, 1877), Robert Briffault (The Mothers, 1927), and Jane Harrison (Prolegomena to the Study of Greek Religion, 1903). They point not only to the existence of universal matriarchy, but also to evidence that it was basically a very different kind of society from patriarchal culture, being egalitarian rather than hierarchical and authoritarian. Bachofen claimed that matriarchal culture recognized but one purpose in life: human felicity. The scholarly proponents of the matriarchal theory maintain that this kind of culture was not bent on the conquest of nature or of other human beings. In brief: It was not patriarchy spelled with an "m." This is an important point, since many who are antagonistic to women's liberation ignorantly and unimaginatively insist that the result will be the same kind of society with women "on top." "On top" thinking, imagining, and acting is essentially patriarchal.

Elizabeth Gould Davis points out that recent archaeological discoveries support these early theories to a remarkable extent. She shows that archaeologists have tended to write of their discoveries that women were predominant in each of their places of research as if this must be a unique case. She maintains that "all together these archaeological finds prove that feminine preeminence was a universal, and not a localized, phenomenon." Davis further comments upon detailed reports that have been made on three prehistoric towns in Anatolia: Mersin, Hacilar, and Catal Huyuk. She concludes that "in all of them the message is clear and unequivocal: ancient society was gynocratic and its deity was feminine. " There is an accumulation of evidence, then, in support of Bachofen's theory of our gynocentric origins, and for the primary worship of a female deity.

-Mary Daly, Beyond God the Father: Toward a Philosophy of Women’s Liberation

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

TIFF 2022: Day 3

Films: 4

Best Film Of The Day: Glass Onion

Butcher’s Crossing: So the question becomes, in Gabe Polsky‘s grim survivalist western, just how many bodies — carcasses — do you need to make your point, even if it’s a good one? The film is actually an anti-buffalo slaughter screed, but in the course of making its, admittedly estimable point, it devotes what seems like an interminable amount of screen time to the shooting, and subsequent skinning, of the animals, which once roamed the plains 30 million strong, but after two decades of brutal mass killing had dwindled down to less than 300 (now, after years of targeted conservation, it’s risen up to 30k, an achievement of no small measure). Leading the charge is, of course, Nicholas Cage, whose half-mad hunter, Miller, sports a Kurtzian shaved head, and a full length fur coat. He’s enlisted by the callow Will (Fred Hechinger), a young man just having left from Harvard, who’s come to see “more of the country,” and, one supposes, experience something real outside of a scholarly tome. In short order, Cage has taken the young man’s money and put together the crew for his dream hunt, off in the Rockies, where years before, he had spied a massive herd, waiting for the right cruel, money-grubbing bastard to come along and wipe them out. Naturally, the trip doesn’t go as planned and the party, including the combatitove Fred (Jeremy Bob), are forced to camp out there through the long, torturous winter, before they can head back with their bloody bounty. The camera tends to stay close on the mugs of the characters, watching every twitch and lurch on their faces, as the mad hunter gets into his frenzy. This is only so effective, as the production is fairly threadbare, and the often shoddy make up doesn’t do anyone any favors. Production value aside, the film’s noble message gets a little chuffed up from its methodology, such that most of the viewers sympathetic to the cause will almost surely get turned off by the sheer amount of shooting and body parts the film sees fit to subject them to.

Women Talking: The title isn’t misleading. In Sarah Polley’s feminist drama, about a Menonite collective, whose women have been abused and raped repeatedly for years by the men, a group of women are elected to determine what to do, after one of the men is caught and identified by some of their younger members. Along with some other perpetrators, the men are hauled off to jail, but are set on getting bailed out by the colony’s male members. The women, including friercely angry Salome (Claire Foy), sweetly firm Ona (Rooney Mara), aggrieved Mariche (Jessie Buckley), and resolute Janz (Frances McDormand), have only a few hours to talk things over up in a hayloft — with meeting notes dutifully recorded by August (Ben Whishaw), the schoolteacher, and the only man any of them can trust — and determine whether the women should forgive the men and stay on, or leave en masse and seek out a new possible future together. There is, shall we say, a lot of discourse on the nature of oppression, exoneration, and their reduced role in the male patriarchy. At times, it plays a bit like a version of 12 Angry Men, but with very different stakes, and involving a group of women in a hayloft. Breaking up the polemic, Polley, working from her own screenplay based on the novel by Miriam Toews, sends her cameras out into the fields, where the children are playing, or into brief flashbacks of the women’s experience. There is also an unrequited love story, between the sweet-minded August, and the independently minded Ona, pregnant with one of the attacker’s children, that helps stave off the static nature of the narrative. There are some unfortunate dramatic tics — a character who suddenly bursts into gales of laughter at inopportune moments, say, or sudden tears — and Polley’s decision to drain her film of all the most desaturated of colors, are distracting, but the central conceit is strong, and the love story (powered largely by Winshaw’s humble recalcitrance) is pretty moving.

Glass Onion: A Knives Out Mystery: How are you supposed to follow-up on one of the more deliriously fun films of the last few years? For Rian Johnson, whose initial foray into the whodunit genre was the delicious Knives Out, the problem isn’t merely to come up with a sequel that matches the original’s playful intrigue and high-energy, but to do it in a way that conjures up a new murder mystery that will keep everyone guessing, exactly when everyone is waiting on it. What he’s come up with is another intricate puzzle within a puzzle — fans of the original remember the way in which the first film seemed to solve itself not quite halfway through, before reinventing itself by the end — in which our understanding of the set of circumstances whiplashes considerably with a single devilish plot twist. The megarich tech tycoon Miles Bron (Edward Norton) has summoned his group of old friends, known amongst themselves as the “disruptors,” to his Greek isle mansion, for their annual gathering of revelry and debauchery, to stage a murder mystery over the weekend. Included on the guest list is Birdie (Kate Hudson), a ditzy formal model now turned entrepreneur, along with her assistant Peg (Jessica Henwick); Duke (Dave Bautista), a “men’s rights advocate with a robust youtube channel, along with his girlfriend Whiskey (Madelyn Cline); Claire (Kathryn Hahn), running for governor in Connecticut on an environmentalist platform; Lionel (Leslie Odum Jr.), one of Bron’s lead scientists for his ubiquitous company, Alpha; and, most shockingly, Cassandra (Janelle Monae), Bron’s former business partner at Alpha, who was recently ousted from the company she co-founded, largely on the strength of everyone else’s betrayal. For reasons somewhat unclear, even to Bron, the “world’s greatest detective” Benoit Blanc (Daniel Craig), has also been summoned for the weekend, a turn that proves fortuitous when bodies start to pile up and Blanc is suddenly thrust into a real investigation, one in which nothing is quite what it seems. Johnson, whose fiendishly clever plotting powers these films with rapturous joy, has created another exultant riddle-ride, in which the cast seems to be having exactly as much fun as the rest of us. While it might not have quite the richly satisfying subtext of the original, that sense of nearly perfect coherency, there is still a tremendous amount of fun to be had, as long as you’re open to Johnson’s blend of precision misdirections, pop-culture jibes, and screwball plot-twistings .

R.M.N.: I have long adored the works of Romanian director Cristian Mungiu (Graduation, 4 Months, 3 Weeks & 2 Days), so any new release of his is cause for celebration. That said, this film, a slow-burning drama set up in the mountains of Transyvania, where jingoism and xenophobia begins to build in a small community when the local bakery starts bringing in workers from Sri Lanka to help with their Christmas rush. Into this seething cauldron returns Matthias (Marin Grigore) a hulking sort of man, who left town some while back to work in Germany. After a violent episode there, he flees the job and comes home, but his fed-up young wife (Macrina Barladeanu) wants nothing to do with him, his 4-year-old son refuses to speak after being scared by something in the woods, and his lover, Csilla (Judith State), upper management at the bakery, is dealing with her own bevy of considerable problems with regards to the growing outrage and death threats made against her new (extremely affable) workers. The film moves in heavily dense scenework — one of the director’s long-held trademarks is filling his frame with different layers of action you have to take in simultaneously — as the characters bounce off one another in ways that become more and more enigmatic. What to make of Matthias, for example, a rigid, violence-prone man who seems utterly uninterested in politics, and far too dense for a intelligent, well-educated woman like Csilla to take an interest, but whose exhortations with his son to snap out of his semi-fugue state are, at times, sensitive and deeply felt? The film trades in these sorts of shades, for the most part, at least until a long, uninterrupted single shot of contentious village gathering at the community center in which the different factions all come together and argue uproariously against the continued presence of the new workers (in a town whose ethnic ties between Roma, Hungarian, and German all chaotically mix together, this distrust of POC is stark). The ending, which will doubtless be the subject for continued debate in film circles, takes a turn for the seeming surreal, further clouding the film’s intentions in the mist. Mungiu has made an impressively oblique film that nevertheless speaks eloquently about this particular political moment in time.

TIFF: One Last Time, wherein the author contemplates this year’s offerings and the past decade of covering this fabulous film festival, as he’s poised to embark on a new career path that will more than likely involve him standing up in front of a group of sullen teens, espousing the glories of the Russian masters, rather than taking in a beatific week of international cinema in the early days of September.

#sweet smell of success#piers marchant#ssos#movies#films#tiff#toronto international film festival#2022#glass onion#rian johnson#daniel craig#edward norton#janelle monae#R.M.N.#cristian mungiu#butcher's crossing#nic cage#women talking#sarah polley#rooney mara#ben whishaw#claire foy#jessie buckley

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

1 note

·

View note

Text

Off-topic, but we discussed Barbie on the podcast this week! Spoiler alerts, so if you haven't seen it, see it first!

0 notes