#it would have been difficult to visually convey that in the old engine since lighting and shadows were all drawn onto the texture map

Text

Kingdom Hearts 3 - Nobodies

#kingdom hearts 3#kh3#nobodies#dusk#sniper#reaper#ninja#gambler#berserker#sorcerer#my gif#i'm a nobody enjoyer so of course i'm gonna make another set with them#nobodies are so reflective in this game i wonder if it they were originally intended to look this way#it would have been difficult to visually convey that in the old engine since lighting and shadows were all drawn onto the texture map#but that's not an issue anymore since there are far less lighting and graphical restrictions#anyways i'm glad we got a couple new nobodies#because their designs rule#i love how the one that represents marluxia can morph its body to look like the pod that sora slept in at castle oblivion#while the one that represents larxene has flowy scarf tails that are reminiscent of her unique hairstyle. the knife hands are cool

573 notes

·

View notes

Text

Researchers hide information in plain text

Computer scientists at Columbia Engineering have invented FontCode, a new way to embed hidden information in ordinary text by imperceptibly changing, or perturbing, the shapes of fonts in text. FontCode creates font perturbations, using them to encode a message that can later be decoded to recover the message. The method works with most fonts and, unlike other text and document methods that hide embedded information, works with most document types, even maintaining the hidden information when the document is printed on paper or converted to another file type. The paper will be presented at SIGGRAPH in Vancouver, British Columbia, August 12-16.

"While there are obvious applications for espionage, we think FontCode has even more practical uses for companies wanting to prevent document tampering or protect copyrights, and for retailers and artists wanting to embed QR codes and other metadata without altering the look or layout of a document," says Changxi Zheng, associate professor of computer science and the paper's senior author.

Zheng created FontCode with his students Chang Xiao (PhD student) and Cheng Zhang MS'17 (now a PhD student at UC Irvine) as a text steganographic method that can embed text, metadata, a URL, or a digital signature into a text document or image, whether it's digitally stored or printed on paper. It works with common font families, such as Times Roman, Helvetica, and Calibri, and is compatible with most word processing programs, including Word and FrameMaker, as well as image-editing and drawing programs, such as Photoshop and Illustrator. Since each letter can be perturbed, the amount of information conveyed secretly is limited only by the length of the regular text. Information is encoded using minute font perturbations -- changing the stroke width, adjusting the height of ascenders and descenders, or tightening or loosening the curves in serifs and the bowls of letters like o, p, and b.

"Changing any letter, punctuation mark, or symbol into a slightly different form allows you to change the meaning of the document," says Xiao, the paper's lead author. "This hidden information, though not visible to humans, is machine-readable just as barcodes and QR codes are instantly readable by computers. However, unlike barcodes and QR codes, FontCode doesn't mar the visual aesthetics of the printed material, and its presence can remain secret."

Data hidden using FontCode can be extremely difficult to detect. Even if an attacker detects font changes between two texts -- highly unlikely given the subtlety of the perturbations -- it simply isn't practical to scan every file going and coming within a company.

Furthermore, FontCode not only embeds but can also encrypt messages. While the perturbations are stored in a numbered location in a codebook, their locations are not fixed. People wanting to communicate through encrypted documents would agree on a private key that specifies the particular locations, or order, of perturbations in the codebook.

"Encryption is just a backup level of protection in case an attacker can detect the use of font changes to convey secret information," says Zheng. "It's very difficult to see the changes, so they are really hard to detect -- this makes FontCode a very powerful technique to get data past existing defenses."

FontCode is not the first technology to hide a message in text -- programs exist to hide messages in PDF and Word files or to resize whitespace to denote a 0 or 1 -- but, the researchers say, it is the first to be document-independent and to retain the secret information even when a document or an image with text (PNG, JPG) is printed or converted to another file type. This means a FrameMaker or Word file can be converted to PDF, or a JPEG can be converted to PNG, all without losing the secret information.

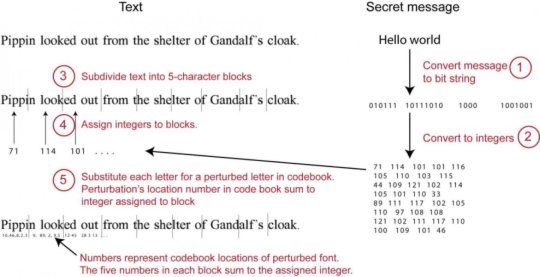

To use FontCode, you would supply a secret message and a carrier text document. FontCode converts the secret message to a bit string (ASCII or Unicode) and then into a sequence of integers. Each integer is assigned to a five-letter block in the regular text where the numbered codebook locations of each letter sum to the integer.

Recovering hidden messages is the reverse process. From a digital file or from a photograph taken with a smartphone, FontCode matches each perturbed letter to the original perturbation in the codebook to reconstruct the original message.

Matching is done using convolutional neural networks (CNNs). Recognizing vector-drawn fonts (such as those stored as PDFs or created with programs like Illustrator) is straightforward since shape and path definitions are computer-readable. However, it's a different story for PNG, IMG, and other rasterized (or pixel) fonts, where lighting changes, differing camera perspectives, or noise or blurriness may mask a part of the letter and prevent an easy recognition.

While CNNs are trained to take into account such distortions, recognition errors will still occur, and a key challenge for the researchers was ensuring a message could always be recovered in the face of such errors. Redundancy is one obvious way to recover lost information, but it doesn't work well with text since redundant letters and symbols are easy to spot.

Instead, the researchers turned to the 1700-year-old Chinese Remainder Theorem, which identifies an unknown number from its remainder after it has been divided by several different divisors. The theorem has been used to reconstruct missing information in other domains; in FontCode, researchers use it to recover the original message even when not all letters are correctly recognized.

"Imagine having three unknown variables," says Zheng. "With three linear equations, you should be able to solve for all three. If you increase the number of equations from three to five, you can solve the three unknowns as long as you know any three out of the five equations."

Using the Chinese Remainder theory, the researchers demonstrated they could recover messages even when 25% of the letter perturbations were not recognized. Theoretically the error rate could go higher than 25%.

The authors, who have filed a patent with Columbia Technology Ventures, plan to extend FontCode to other languages and character sets, including Chinese.

"We are excited about the broad array of applications for FontCode," says Zheng, "from document management software, to invisible QR codes, to protection of legal documents. FontCode could be a game changer."

305 notes

·

View notes

Photo

New Post has been published on https://warmdevs.com/branding-an-intranet.html

Branding an Intranet

Most Intranets are created and owned by IT, HR, Corporate Communications, or a combination of these departments. While these teams have the necessary skills to create and maintain great intranets, they don’t usually include experts in branding. Thus, intranets frequently lack a brand identity. A weak or nonexistent intranet brand leads to poor credibility, adoption, and acceptance.

Any intranet team can improve the intranet branding by focusing on a few key elements —name, logo, relationship with the public-facing website — that can have the biggest impact.

Name of the Intranet

It’s important for an intranet to have a name, for two main reasons:

Identity: The name conveys the intranet’s goal and identity. An intranet called Center, for example, can suggest to employees that it is the place where everyone congregates and gets information. An intranet called Harmony could indicate that groups recently merged or acquired will be working together.

Reference: Employees use the name of the intranet to refer to it in speech and writing. The name should be easy to remember, spell, and pronounce. Employees should never wonder how to say the name of the intranet and they should not be embarrassed or shy about saying it.

These points may sound obvious, but many intranets have no name, so employees don’t know how to refer to them.

Other intranets have names, but they are not helpful. An acronym, an uncommon word, or a play on words may seem like good ideas, but they can backfire. For example, imagine that a Texas-based company named its intranet FacTX — a name that combines the word “facts” (to indicate that the intranet houses factual information for employees) with the Texas state abbreviation “TX”.

Clever, but when I have tested intranets named like this, employees have been confused. Some employees would pronounce the name “facts”, but others would pronounce “fac T X” like three separate words or “factucks”, pronouncing the last two letters. Others would just mumble the name, say they feel silly, or say outright, “I never know how to pronounce that.”

By far, the most common names for intranets I have encountered are:

Intranet

Portal

Inside <Company Name>

<Company Name> Hub

These names may seem unimaginative, but in practice they work quite well. Feel free to use one of these straightforward names for your intranet, provided there are not multiple intranets or other apps at the organization that could be confused with the intranet.

Sometimes crafty names can be effective, however. For example, several years ago we studied American Airlines’ intranet, named JetNet. This name remains one of my favorite intranet names because it had all these traits:

easy to pronounce

easy to spell

not confusing

whimsical (rhyming) element

related to the company’s purpose

lasting

underlying a subtle theme: that employees would be fast at getting things done when they used the intranet

This kind of cagey intranet name doesn’t come easily. If you want to try one, test it out with employees before implementing it. And think about whether the name can last for years to come. Getting people to call the intranet by a different name is difficult. They will still refer to the intranet by the old name, especially it if was catchy. So, choose a name your organization can live with at least until the next time the intranet is greatly modified, and you want to change the name to indicate that transformation.

The Intranet Logo

Often, a good logo for an intranet includes simply the intranet’s name, with no other fanfare. It is positioned in the upper left corner on all site pages and indicates to employees where they are in their organization’s digital workplace.

Four of the 10 intranets that won NN/g’s 2018 Intranet Design Annual contest included the intranet name only as their logo.

Many intranets use the company logo along with the intranet name. This practice is effective and differentiates the intranet from the public-facing website, while still supporting the organization’s brand.

Five of the 10 intranets that won NN/g’s 2018 Intranet Design Annual contest used the company logo along with the intranet name.

Using only the company’s logo by itself to denote the intranet can be confusing, since that logo usually appears on the public-facing website and employees may thus have a hard time distinguishing the internal pages from the external ones. Also, users won’t know if the company logo on the intranet will link to the company’s homepage or to the intranet’s homepage.

Intranet teams may consider creating an elaborate, separate logo for the intranet if they have the needed resources. While usually unnecessary, it can help indicate to employees that they are on the intranet and can foster the intranet’s identity.

Matching the Public-Facing Website

The colors and fonts used in the intranet’s visual design often closely match those used on the organization’s public-facing website, since intranets usually adhere to corporate branding guidelines. In theory, it’s a good idea to for the intranet to support the organization’s sanctioned branding, but should the intranet look and feel the same as the public-facing website?

The answer depends on the goals of the intranet and the organization. After all, the users of the intranet are probably not the same as the customers of the company, and thus, the goals of the website and the intranet often differ. For example, it’s common for organizations to project externally a tone of voice that is professional, credible, and informative; that same organization may choose a fun, light-hearted, and open-minded tone to communicate with employees. While these goals are not at odds, they are different and affect design and content.

In shaping the design of the Intranet, consider the following dimensions:

audience: tasks, needs, desires, ages, and so on.

technology supporting the development: confined to an intranet system or highly flexible

capabilities for development: engineers at hand who can control and adapt the software you use

On each of these dimensions, the company’s public site and the intranet may or may need to match. For example, for the hypothetical situation below, none of the dimensions should match.

Audience Technology Capabilities Public-facing website Millennials Opensource that’s highly flexible Full-time large team, fair budget, fair timeline Intranet Millennials, Gen-X, Baby Boomers Intranet solution that does the heavy lifting, but dictates much of the UI design Part-time small team, small budget, short timeline Match No No No

If the audiences for the internal and external sites are different, you will need to adopt a different tone of voice (for example, you may want an amusing yet concise one for your intranet’s millennial audience; and a professional, image-rich one for the public site’s audience) and possibly even different visual design. Still, the intranet can adhere to branding guidelines by using the same color palette and typeface.

When considering the relationship between your internal and external-facing sites, follow these recommendations:

Give the intranet the look and feel it needs to meet its goals.

Be careful not to make it so drastically different from the corporate branding that it doesn’t seem to be part of your organization.

Don’t make it look so much like the public-facing website that employees can’t tell the difference between them.

Don’t make the intranet your personal art project. Just because the intranet is free from corporate style guides shouldn’t give the intranet team license to do anything.

Don’t Overbrand the Intranet

While some intranets have little or no branding, others suffer from overbranding. Avoid these common overbranding pitfalls:

Don’t attempt to brand features by giving them a catchy name. For example, the area for posting a document doesn’t need to be called Upload Wizard. A descriptive label such as Upload a Document is fine. A set of links doesn’t need to be branded as Quicklinks. Even the very best intranets in the world offer quicklinks so you are in good company if you have them, but this is no excuse. Name that section something less vague, such as important links or popular links.

Rethink using third-party–software brand names. For example, rather than using SAS or Citrix as link or menu terms, use labels such as Job postings or Schedule a meeting that carry stronger information scent for your employees. consider whether naming them for the user’s task—like—might be more understandable terms.

Conclusion

Your intranet name should prime your employees to think of the experience they will have while using it. Choose a name your organization can live with for a long time. Consider renaming the intranet if it has been redesigned, since a new name and a fresh look can signify to employees that the new design is better and more usable.

0 notes

Text

If only… The friends I’ve lost in airplane accidents

I’ve struggled with writing about this tragedy for a long time. I wanted so much to give other pilots a glance at this image, hoping a few might take a moment before a flight to see if there were any gotchas they missed amid their haste and distractions. But I recoiled against the prospect of telling a very personal, painful, and graphic story about a good pilot buddy. Finally I decided to just start writing rather than let this opportunity die along with him, though I must protect his anonymity. I’m certainly not a writer, nor have I ever written anything for public consumption. I may never again. This is straight from the heart.

Hundreds and hundreds of people. Family, friends, business associates, and employees. Every seat in the large church sanctuary filled. Others standing along the walls. The foyer and hallways so crowded that more stand around outside, roasting in the sun, straining to hear the memorial service being broadcast on speakers. All the parking lots filled, with illegally parked cars choking the roadway for hundreds of yards in both directions. No dry eyes. So many lives so profoundly impacted. So many futures changed forever. If only…

My friend and his passenger died in an airplane crash.

“This has become a far too frequent occurrence for me.”

I’ve seen turnouts like this before, when young men die suddenly and violently while living life to the fullest. These gentlemen were well known and respected in their community and businesses, and served others for most of their time on this earth. They were humorous, articulate, and responsible. They loved and provided well for their families, friends, and employees. In our busy age it’s a great tribute that so many have made the effort to pay their respects and offer comfort and condolences to the suffering families as they start dealing with their own grief.

This has become a far too frequent occurrence for me, and I’m getting a little tired of it. I’ve lost sixteen friends and numerous acquaintances in aircraft mishaps. So far. Of my friends, four died in military training and combat, and all the rest in general aviation. Nearly all were highly skilled, with decades of experience in all sorts of aircraft and conditions. And I miss these good men and women every single day.

Oddly enough, I don’t personally know anyone who survived a GA crash where others died. This might be due to the nature of flying in a part of the country with very challenging terrain and weather. But records show that terrible, life-altering injuries are frequent. A common trait among pilots is a highly developed sense of responsibility for protecting our passengers. I can’t begin to imagine the lifelong load of guilt a pilot must have to carry after killing or maiming people who trusted their lives to them.

So how do qualified, well-trained pilots lose their lives? My friends perished due to various causes: continued VFR into IMC, midair collision, severe turbulence in mountains, flight control malfunction, low altitude stall/spin, descending below approach minimums in IMC, flying up blind canyons, attempting a go-around from a one-way strip, and catastrophic engine failure. There was no hotdogging, buzzing, or overt recklessness involved. These all should’ve just been normal flights.

Come to think of it, I’ve only known one person who died in a traffic accident, and he was on a motorcycle. Anyone who tells you that flying is safer than driving is probably talking about airline flying. Either that or they’re misinformed. And in this instance at least, the old flying adage holds true: “… if you crash because of weather, your funeral will be held on a sunny day.”

Please don’t get the wrong impression. I love aviation. I’ve been completely passionate about it since I was a toddler. In fact, the first thing I want to do after coming home from work (if you can call it “work” — I fly for a living) is go flying in little airplanes. Hey, I’m sick! I need help!

But these losses have changed me. I find myself double checking so many mundane things, and kicking myself if I discover anything I’ve missed. Much of the time that I used to take to enjoy the view is now crowded out by going over the “what ifs.” I experienced an engine failure a few years ago, and now I hear my inner monologue saying things like, “There’s a good place to deadstick it in! There’s another! And another!” But I know that I can’t possibly account for everything that could bring me down.

Accident reports rarely convey just how awful an airplane crash really is.

This nagging understanding makes me refuse to take the chances that I might have in the past, like taking more than one grandchild up in my airplane at a time, or trusting that the destination weather will improve by arrival time. It also makes me less willing to fly hard IFR when I’m not at work. That’s too much like work, anyway, and I bought my airplane for blue skies and beautiful days. Most of all it makes me realize that I’m not invincible. But if this risk aversion makes me a safer pilot, then it’s all worth it.

We’ve all read the accident reports, full of terms like “high degree of energy dissipation upon impact” and “rapid descent into terrain.” But this kind of cold, clinical language disguises the real aftermath: the disrupted, often destroyed lives of loved ones, the hardship and loss experienced by those left behind, and the horrors they can never forget. These reports seldom let us see through that veil, but we MUST look beyond and understand the massive consequences our actions or omissions might bring.

We’ve all seen or heard of bad examples of airmanship, ranging from ignorance to foolishness to false bravado. But in dealing with all my personal aviation tragedies, I’ve found some things common to most: complacency, overconfidence, inadequate planning, lack of qualification or competence, and lack of preparation. But the biggest contributor to my buddy’s fatal crash: very poor judgment.

This is a difficult thing for me to say about my pal, especially since I had been something of a mentor to him. But I have to put it right out there in the hope that it might save a life someday. Besides, who among us hasn’t displayed poor judgment at one time or another, especially when acting as a pilot?

Get-home-itis was the biggest link to the faulty judgment in this tragedy. It is a powerful force, so powerful that both men aboard were willing to risk single-engine flying over unlit mountainous terrain. In the middle of the night. Without a discernible horizon or an instrument rating. In smoke, clouds, and turbulence. With the moon adding all sorts of visual illusions. And with embedded thunderstorms along their route.

This combination of factors produced very unsurprising results: classic spatial disorientation followed by the inevitable graveyard spiral and final dive, terminating with high-speed vertical descent into terrain under full power. There was no in-flight breakup. The impact was so powerful that body parts were scattered up into surrounding trees, according to the sheriff’s report. This ghastly image haunts me still, and I wasn’t even one of the poor souls who had to clean up the mess. Human remains were so fragmented that no one could determine what belonged to whom. Even the credit cards in their wallets were shattered. And undoubtedly those who responded to this disaster will never be able to unsee what was laid out before them.

What haunts me even more is imagining what those last moments in the cockpit were like. I can hear the shrieking of the air rushing over the airframe at well over 200 knots, feel the disorienting g-loading, and sense the overwhelming terror that they must have experienced in the eternity of the last few seconds of their lives as they plunged into the blackness. I can only imagine how the thought of this must sicken their loved ones. The only upside? It didn’t hurt for long.

Even celebrities aren’t immune to VFR-into-IMC accidents, as Kobe Bryant tragically learned.

Disasters like this are far too common in general aviation. Some 40% of GA accidents are caused by spatial disorientation, yet it is not commonly understood. Remember JFK Jr? Ever hear of “The Day the Music Died?” What about Patsy Cline? Kobe Bryant?

As a matter of fact, my friend did call other pilot friends that night to get their advice, which he quickly disregarded. They begged him to spend the night and come home at first light. Now they will be forever plagued by thinking that they could have done more to convince him. But obviously he had his mind made up, and was only looking for affirmation. After all, both victims had nonrefundable reservations for their families’ vacation together starting the following day. If only…

Calling a “knock-it-off” would have cost them this vacation. Well, so did pressing on.

If only my buddy could have been given even a tiny glimpse into the future, he could have avoided the horrible results of his decision.

The real tragedy is that he did have the opportunity for that glimpse.

This outcome was foreseeable. His actions under these conditions had predictable results. But here’s the worst thing: He had just come through these conditions on the same route as his ill-fated return flight, and he KNEW what was ahead!

Much of airmanship is managing risk. Of course, awful things just happen sometimes (i.e., catastrophic structural failures), but this disaster was caused by easily avoidable and well-known risk factors.

I plead with any of you who face the host of decisions that comprise every flight to take one moment and play the pessimist. I know we all hate to think about this, but how high will the cost be if not everything goes your way? Look at how all your people would be affected if something life changing, or life ending, were to happen on your flight. Think about how overall risk jumps when a few bad little things happen at about the same time. Have an escape plan for when things do go wrong. Can you divert? Is there landable terrain below you if you have to put it down? Are you properly equipped to survive the aftermath of a remote landing? Can you see well enough to land there? Can you flip a “U-ey” in time to get out of a bad situation? Where are the rocks? What about going tomorrow (or next week) instead? Always leave yourself an out.

Better yet, leave yourself lots of outs. Here are some examples: before you push up the power, take an extra minute to consider the worst case. Double check weather and NOTAMS. Consider your gross weight and performance. Ask for advice. Know where your possible divert fields are. Think about the true priorities. Learn about spatial disorientation and how insidious it is. Beware of overconfidence and complacency. Assess and manage your risk. Take your solemn responsibility for your passengers seriously. Realize that even if you’re solo, you are risking the lives of your loved ones. Don’t get in a rush. And never let yourself start thinking that you’re bulletproof.

There’s already plenty of risk in this life. Aviation brings more, whether we like to admit it or not. Manage it well and you can enjoy a lifetime of fun sharing this great gift of flight!

The post If only… The friends I’ve lost in airplane accidents appeared first on Air Facts Journal.

from Engineering Blog https://airfactsjournal.com/2020/05/if-only-the-friends-ive-lost-in-airplane-accidents/

0 notes

Text

A Child's Work Is to Play

New Story has been published on https://enzaime.com/childs-work-play/

A Child's Work Is to Play

The playroom of Kennedy Krieger Institute’s Achievements program doesn’t look like a typical child’s playroom. There are no blocks, books, dolls or trucks lining the shelves or scattered about the floor. In fact, the room seems practically devoid of toys, those things that inspire the imaginations of children but it’s not. They’re here, stored neatly in clear plastic bins, one to a container, each labeled with a picture and a word describing its contents.

This room at Achievements has been carefully engineered to be easily navigated by children with autism, whose neurological impairments interfere with their natural ability to play. For most children, playing is a spontaneous act, inspiring a host of social and communication skills that are important to healthy development. Children with autism and other neurologically based disorders, as well as traumatic brain injuries, often have impairments that make it difficult to play in traditional ways. But with therapeutic interventions, support and special environments such as the highly organized playroom at Achievements, play for these children is becoming less work and more fun.

Breaking play down into steps

Children with autism disorders have trouble playing because of neurological impairments that interfere with their ability to interact with their environments. These are children who explore their environments in an idiosyncratic fashion, not allowing others to fully participate. They do not play with toys in a conventional way; they must be guided. And that is essentially what Achievements Speech/Language pathologist Emily Tyson is doing when she directs 5-year-old Keith Carter to a small table by the window in the playroom. It is time to play with blocks.

“Shapes” reads the bin on the low table where they sit. Tyson points to the picture beside the word a ball and blocks and she encourages Keith to pick out the triangle block and drop it in the appropriate hole. Not only does she cue him with the picture as she speaks to him, slowly and distinctly, she uses American Sign Language. Though Keith is not hearing impaired, he has difficulty understanding the words he hears; it is as though what he hears is a foreign language that he cannot grasp for his brain does not process language appropriately. But through pictures and signs and a host of therapeutic interventions, Keith and other children like him can develop some capacity for using spoken language.

Much of the therapy that children receive at Achievements is aimed at teaching them how to play, for play requires the very skills that autistic children lack: communication, interaction with peers, the ability to engage in meaningful sequences of activities. Keith may lack the skills to play, but he obviously has the desire. When his teacher produces a big blue pompom, he shakes it, delighting in the motion, and he snaps it in her direction, teasingly, as though he’s going to swipe her with it. He chortles with delight at the prospect. But that is where it stops. In spite of the teacher’s response and her cueing, the gesture is isolated. What seemed an overture, the beginning of a game, is fleeting and never goes beyond an inclination. “Play requires sequencing and social interaction, and Keith doesn’t have the natural ability that unaffected children have for that,” Tyson explains. “So we teach him, step by step.”

The teachers and therapists at Achievements take children like Keith through the motions, and through their repetition, they learn the sequence. Eventually, they generalize it into their everyday interactions. Keith’s grandmother, Diane Armstrong, testifies to that. “Keith has really come out since he came into the program. Before, it was like he was in his own little world. Now he plays – but they’ve made him do it. I remember he used to be afraid to go up a ladder [to a slide]. His teachers made him do it, step by step, and he learned. But he was just never inclined to do it on his own to explore, like other children.”

The staff at Achievements is looking forward to the completion of a new playground, made possible through funding from the Chatlos Foundation and the Goldsmith Family Foundation, that is under construction on Kennedy Krieger’s Greenspring Campus where Achievements is located. “It will enable us to provide children with incredible opportunities to acquire the skills they need to play,” says Tyson. “The playground provides a highly motivating environment to teach language and play skills through movement.” She explains that she will use picture symbols in the classroom that correspond to pictures labeling the equipment outside to plan sequences of activities, such as, “First slide, then swing on the tire, then climb up to the platform.” A picture schedule will allow Keith to organize his play, as he will revert to his compulsive, repetitive movement without it. “For Keith, the slide is just the beginning,” Tyson says. “There’s a whole new playground and world out there for him to explore!”

Inspiring motivation, learning through play

Quanir JohnsonYoungsters at Kennedy Krieger’s rehabilitative unit for children and adolescents with brain and spinal cord injuries are, on the other hand, relearning how to play. The purpose of the unit’s Child Life and Therapeutic Recreation Department is to improve or maintain children’s physical, cognitive, emotional and social functioning through recreational activities. A peek into the game closet in the department’s therapeutic playroom conveys the complexity of the challenges that these young patients face. Aggravation, Amnesia, Bonkers! Clue, Memory, Monopoly, Out-Burst! Rage!, Risk, Sorry, Solitaire, Scattergory, Uno, and The Game of Life. In the cases of the children here, the names of these games have literal meaning. A child may engage in a game of Clue, not just for fun, but to help her re-establish the memory and inductive reasoning skills that were lost as a result of a traumatic brain injury.

On this day, 9-year-old Da’Naisha Cox hoots and hollers her way through a rousing game of air hockey with her therapist, Sharon Borshay. Da’Naisha is lithe, possessing of that special gracefulness held by all natural athletes. Da’Naisha was an athlete in the making before the seizures caused by Lennox Gastault Disorder, a form of epilepsy, became severe. According to her grandfather, she walked at 9 months, and he proudly recounts how she rode her bike around the entire perimeter of Fort McHenry Park, without training wheels, when she was only 5. But following a prolonged seizure a month ago, Da’Naisha is now challenged by difficulty with speech and movement. As she sweeps her arm across the board to intercept the puck and keep her opponent from scoring, the motions are inexact, and her commentary through the course of the game slurred beyond recognition. But the desire is there, the desire to play. Caught up in the spirit of competition, she reaches further with her arm than she otherwise would, and her attempts at communication are persistent for after all, she must know who is winning and what’s the score. Da’Naisha has challenges to overcome, and play will be a major tool in the rehabilitative process. “Play is what engages children,” says Borshay. “In this department we use play, games, toys and humor to motivate the kids and keep them learning. Play is how we get kids to cooperate, to take part in their recovery, to go the extra mile.”

Creative environment heightens children’s senses

Meanwhile, in a highly specialized setting at Kennedy Krieger affiliate, PACT: Helping Children with Special Needs, play is being taken to a whole new level. In the recently completed multi-sensory playroom, made possible through a grant from the Garth Brooks Foundation, children with a wide variety of neurologically based disorders are given opportunities to experience sensory stimulation that their disabilities would otherwise preclude. Toys and objects specially designed to provide high contrast colored light are perceptible to children with visual impairments. For children with hearing impairments, there are cushions that vibrate with the pulse of music, giving them a means to experience the sound. The special equipment in the multi-sensory room gives the children at PACT tools that enable them to play, and through their play, to develop cognitive skills that might otherwise be unattainable.

The stimuli in the room can be controlled to meet children’s individual needs. For a child who is unable to filter stimuli from the environment, and therefore is prone to becoming too distracted to concentrate and learn, the lighting can be dimmed, soothing music played, and his attention turned to a toy or a game that targets development of specific skills. For a child whose impairments cause sensory deprivation or lowered motivation, the room can be transformed into a highly stimulating environment. On the occasion of 2-year-old Terrance Ridley’s therapy session with his speech/ language pathologist Holly Gardiner, the room takes on the atmosphere of a discothèque.

As Terrance sits in Gardiner’s lap, he watches a floor-to-ceiling Plexiglas column filled with bubbling, colored water, and he is wide-eyed with amazement. Gardiner guides his hand to the big blue button on a switch box she has placed in front of them and presses his hand to the button. The water turns blue! Clearly excited by the effect, Terrence raises his eyes to take in the full length of the bubbling tube, in itself an achievement for this boy who is challenged to use a full range of vision. Terrance’s visual impairment is but one manifestation of the cerebral palsy that his limits range of motion, muscle control and strength, impacting his ability to sit, walk, reach and speak. But over the course of this session, Terrance reaches for and presses the button, sits with less support than he generally requires and uses his right hand, that which is most affected by excessive muscle tone problems and which he seldom favors.

The contrast between light and darkness provided by the bubble column and other apparati in the room provides useful visual opportunities for 3-year-old Quanir Johnson, as well. Quanir is visually impaired and has cerebral palsy and serious cognitive deficits. In the multi-sensory room, Qaunir is held in a supported position by his occupational therapist, Dan Eisner. His speech/language pathologist, Nancy Solomon, is nearby. When presented with long, plastic spaghetti-like strands of light, Quanir holds up his head and his eyes move, tracking them. Solomon is pleased to see him responding to the environment and encourages him to imitate the vowel sounds she makes the beginnings of communication. Not today. Quanir is so relaxed by the experience that he is falling asleep. His therapists are very pleased with his accomplishments and a discussion ensues as to how they can use the room to achieve therapeutic goals of other children in their care.

#autism disorders#big blue pompom#cueing#Gardiner's lap#meaningful sequences#therapeutic interventions#Autism

0 notes

Text

Flight directors – a fatal attraction

My first encounter with flight directors was in 1966 while undergoing conversion to the Avro 748. The RAAF had seen fit to send me to Woodford in Cheshire, all the way from Australia, to ferry the second of several new 748s for the RAAF VIP squadron at Canberra. The conversion was conducted on a battered 748 demonstrator: G-ARAY, known as Gary. The contract allowed four hours of dual for the captains and nothing for the co-pilots. G-ARAY had the basic instrument flying panel of that era and no flight director.

Our instructors at Avro’s were well-known test pilots Bill Else, Tony Blackman and Eric Franklin. Jimmy Harrison was chief test pilot. Unlike the bog-standard civilian 748, the RAAF 748s were to be equipped with a Collins FD 108 FD. So the situation existed that the RAAF 748s had a British Smith’s autopilot system which was married (somewhat expensively and painfully) to the American Collins FD 108.

For the life of me, I could not see why a flight director was needed in the RAAF 748. After all, the approach speed was that of a DC-3 (80 knots) and the aircraft a delight to handle compared with the venerable Dak.

Did the Avro 748 really need a flight director?

In retrospect, I think the old Wing Commander Transport Ops at Department of Air, who was charged with the procurement of the 748 for RAAF service, and hadn’t flown for years, was perhaps conned by the Avro sales people, in conjunction with Collins, into buying the Collins systems. Certainly in my view as the squadron QFI, flight directors were not operationally needed. In the event, the RAAF machines came with Collins FD 108 flight directors and, as the contract specified, each captain would be given only one hour of dual instruction once the 748 came out of the factory. We needed to learn how to operate the FD.

First, a course was arranged at the Collins establishment at Weybridge in Surrey. The two RAAF captains and their co-pilots attended and our two navigators and our instrument fitters also turned up to enjoy the Collins hospitality. We learned about 45 degree automatic intercepts of the VOR and ILS beams and other goodies including V-bar interpretation. We were showered with glossy brochures of the flight director by white dust-coated lecturers and shown a film.

By lunch time, the presentation was complete and we were shouted to a slap up pub meal with lots of grog, all paid for by Collins. We asked what further lectures were to take place after lunch. We were told the course was over – it was just a morning’s job and we were free to leave unless we would like more drinks. Naturally it was churlish to refuse and hours later we staggered to the railway station (I think), smashed to the eye balls and having forgotten all about the marvels of 45 degree auto intercepts on the FD 108. I must say it was a bloody good three-hour course what with the free grog and all that.

A few weeks later, I flew the second RAAF aircraft out of the factory, A10-596, under the watchful eye of Eric Franklin DFC and he demonstrated flight director stuff. For example, to climb using the FD, you first put the aircraft into a normal climb and when settled you switched on the FD and carefully wound up the pitch knob so that the little aeroplane sat in the middle of the V-bars.

I quickly realised that you hand-flew the basic artificial horizon to whatever attitude was appropriate for the manoeuvre then told the FD 108 V bars where you wanted them. The ILS intercept of 45 degrees was never used because radar vectors didn’t do such angles. I became more and more convinced the 748 didn’t need flight directors and that they were a load of bollocks in that type of low speed aircraft. We were told the USAF used the FD 108 in its F4 Phantoms and that Collins was anxious to makes sales in the UK market.

The RAAF Wing Commander got sucked in by good sales talk and from then on all RAAF 748s became so equipped. I held personal doubts about the usefulness of flight directors in general as I could see even then their extended use could lead to degradation of pure instrument flying skills. Today’s flight director systems are light years ahead in sophistication compared with the old Collins FD 105 and 108 series. But the problem with blind reliance on FD indications and thus steady degradation of manual instrument flying skills is as real now as it was back in 1966.

Now to the present day – although first some background history. First published in 1967, Handling the Big Jets, written by the then British Air Registration Board’s chief test pilot David Davies, is still considered by some as the finest treatise still around on jet transport handling. Indeed, the book was described by IFALPA as “the best of its kind in the world, written by a test pilot for airline pilots… the book is likely to become a standard text book… particularly recommended to all airline pilots who fly jets in the future… valuable to those pilots who are active in air safety work.”

Do these flight directors make flying safer or pilots lazier?

All that was back in 1967 and little has changed since then – apart from an increasing propensity for crashes involving loss of control rather than simply running into hills. LOC instead of CFIT. Mostly these accidents were caused primarily by poor hand flying and instrument flying skills, which certainly explains why aircraft manufacturers lead the push for more and more automatics.

A colleague involved with Boeing 787 training was told by a test pilot on type, that the 787 design philosophy was based on the premise that incompetent crews would be flying the aircraft and that its sophisticated automatic protection systems were in place to defend against incompetent handling. Be it a tongue-in-cheek observation, it contains an element of truth. With the plethora of inexperienced low-hour cadet pilots going directly into the second-in-command seats in many airlines in Asia, the Middle East and Europe, these protection systems are important.

Towards the end of his book, David Davies discusses the limitations of the flight instruments in turbulence and in particular the generally small size of the active part of the basic attitude information or the “little aeroplane” as many older pilots will remember it. He continues: “The preponderance of flight director and other information suppresses the attitude information and makes it difficult to get at” and “the inability, where pitch and roll information is split, to convey true attitude information at large pitch and roll angles in combination.” Finally Davies exhorts airline pilots “not to become lazy in your professional lives… the autopilot is a great comfort, so is the flight director and approach coupler… but do not get into the position where you need these devices to complete a flight.” There is more but go and read the book.

Having done the unforgiveable and quoted freely from an eminent authority, it is time to say something original and accept the no doubt critical comment that is freely available. Flight Directors can be a fatal attraction to those pilots who have been brain-washed by their training system to rely on them at all times. While Boeing in their FCTM advise pilots to ensure flight director modes are selected for the desired manoeuvre, it also makes the point that the FD should be turned off if commands are not to be followed.

Recently a new pilot to the Boeing 737 asked his line training captain if he could turn off the FD during a visual climb so he could better “see” the climb attitude. His request was refused as being “unsafe” and instead he was told to “look through” the FD. I don’t know about you, but I find it impossible to “see” the little aeroplane when it is obscured by twin needles or V-bars. In fact, it takes a fair amount of imagination and concentration to do so. Which may be why Boeing recommends pilots to switch off the FD if commands are not to be followed.

I well recall my first simulator experience in the 737 of an engine failure at V2 where I was having a devil of a time trying to correct yaw and roll and the instructor shouting at me to “Follow the bloody flight director needles.” I learned a good lesson from that tirade of abuse on how not to instruct if ever I became a check pilot. In later years, having gravitated to the exalted – or despised maybe – role of simulator instructor, my habit was to introduce the engine failure on takeoff by first personally demonstrating to the student how it should be done on raw data; meaning without a flight director. I hoped by first demonstrating, the student could see the body angles or attitude rather than imagine them by trying to “look through” the dancing needles of the FD. I have always been an advocate of the Central Flying School instructional technique of demonstrate first so the student then knows what he is aiming for. Of course in the simulator, the instructor runs the risk of stuffing up (been there – done that!) but it at least proves he is human and not just another screaming skull.

General aviation pilots are no strangers to flight directors either, especially as glass cockpits become more popular.

Recently, a 250-hour pilot with a type rating on the 737-300 (and trained overseas) booked a practice session prior to putting himself up to renew an instrument rating. His last rating was on a BE76 Duchess. As part of the 737 instrument rating would include manual flying on raw data, he was given a practice manual throttle, raw data takeoff and climb to 3000 ft. He protested, saying he had never flown the simulator without the flight director.

His instructions were to maintain 180 knots with Flaps 5 on levelling. He was unable to cope and when the instructor froze the simulator to save more embarrassment, the student was 2000 ft above cleared level and 270 knots – still accelerating with takeoff thrust. The student had been totally reliant on following flight directors with their associated autothrottles during his type rating course, and without this aid he was helpless.

I believe this is more widespread than most of us would believe, especially as we tend to move in our own narrow circle of experience.

At a US flight safety symposium, a speaker made the point that it is the less experienced first officers starting out at smaller carriers who most need manual flying experience. And, airline training programs are focused on training pilots to fly with the automation, rather than without it. Senior pilots, even if their manual flying skills are rusty, can at least draw on experience flying older generations of less automated planes.

Some time ago, the FAA published a Safety Alert for Operators (SAFO) entitled Manual Flight Operations. The purpose of the SAFO was to encourage operators to promote manual flight operations when appropriate. An extract from the SAFO stated that a recent analysis of flight operations data (including normal flight operations, incidents and accidents) identified an increase in manual handling errors and “the FAA believes maintaining and improving the knowledge and skills for manual flight operations is necessary for safe flight operations.” Now let me see, I recall similar sentiments nearly 50 years ago published in Handling the Big Jets when David Davies wrote that airline pilots should “not become lazy in your professional lives… the autopilot is a great comfort, so is the flight director and approach coupler but do not get into the position where you need these devices to complete the flight.” See my earlier paragraphs.

It is a good bet that lip service will be paid by most US operators to the FAA recommendation to do more hand flying. It may have some effect in USA but certainly the majority of the world’s airlines, if they were even aware of the FAA stance in the first place (very doubtful), will continue to stick with accent on full automation from lift off to near touch-down and either ban or discourage their pilots from hand flying on line.

If you don’t believe that, consider the statement in one European 737 FCOM from 20 years ago that said: “Under only exceptional circumstances will manual flight be permitted.” After all, when at least two major airlines in Southeast Asia have recently banned all takeoff and landings by first officers because of their poor flying ability, then what hope is there to allow these pilots to actually touch the controls and hand-fly in good weather? One of those airlines requires the first officer to have a minimum of five years on type before being allowed to take off or land while the other stipulates the captain will do all the flying below 5000 ft. It might stop QAR pings and the captain wearing the consequences of the first officer’s lack of handling ability, but it sure fails to address the real cause and that is lack of proper training before first officers are shoved out on line.

Sometimes you have to put your hands on the controls and fly raw data.

I think the FAA missed a golden opportunity in its SAFO to note that practicing hand flying to maintain flying skills will better attain that objective if flight director guidance is switched off. The very design of flight director systems concentrates all information into two needles (or V-bar) and in order to get those needles centered over the little square box, it needs intense concentration by the pilot. Normal instrument flight scan technique is degraded or disappears with the pilot sometimes oblivious to the other instruments because of the need to focus exclusively on the FD needles. Believe me, we see this in the simulator time and again. Manual flying without first switching off FD information will not increase basic handling or instrument flying skills.

The flight director is amazingly accurate provided the information sent to it is correct. But you don’t need it for all stages of flight. Given wrong information and followed blindly, it becomes a fatal attraction. Yet we have seen in the simulator a marked reluctance for pilots to switch it off when it no longer gives useful information. Instructors are quick to blame the hapless student for not following the FD needles. This only serves to reinforce addiction to the FD needles as they must be right because the instructor keeps on telling them so. For type rating training on new pilots, repeated circuits and landings sharpen handling skills. Yet it is not uncommon for instructors to teach students to enter waypoints around the circuit and then exhort the pilots “fly the flight director” instead of having them look outside at the runway to judge how things are going.

First officers are a captive audience to a captain’s whims. If the captain is nervous about letting his first officer turn off the flight director for simple climbs or descents, or even a non-threatening instrument approach, then it reflects adversely on the captain’s own confidence that he could handle a non-flight director approach. The FAA has already acted belatedly in publicly recommending that operators should encourage more hand flying if conditions are appropriate. But switch off the flight directors if you want real value for money, particularly with low-hour pilots. It may save lives on the proverbial dark and stormy night and the generators play up.

The post Flight directors – a fatal attraction appeared first on Air Facts Journal.

from Engineering Blog https://airfactsjournal.com/2018/04/flight-directors-a-fatal-attraction/

0 notes