#italy1815

Text

Helfert, Joachim Murat - Index

Translations from Joseph A. Helfert, “Joachim Murat. Seine letzten Kämpfe und sein Ende”

Text:

Chapter 1: Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, Part 5

Chapter 2: Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4

Chapter 3: Part 1, Part 2, Part 3

Chapter 4: Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, Part 5, Part 6

Chapter 5: Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4

Chapter 6: Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, Part 5, Part 6

Chapter 7: Murat’s heirs

Annex and related documents:

1811: Three letters by Austrian diplomats

October 1812: Letter from Mier to Metternich

Spring 1813: Letters from Mier to Metternich

[October 1813: Murat stops in Milan. That’s not from Helfert’s book but it fits in so nicely.]

January 1814: Mier’s situation report on his return to Naples

March 6 - 9, 1814: Battle at Reggio. Murat arguing with Bellegarde (while Eugène is picking flowers)

March 8, 1814: Letter from Metternich

March 1814: Letters relating to the relationship between Murat and Bentinck

March 1814: Letters from Murat, Eugène and Mier (Murat and Eugène still writing to each other)

September 1815: Royal decree

September/October 1815: Proclamation to the Neapolitans

October 1815: Last documents related to Joachim Murat’s death

#helfert murat#joachim murat#caroline murat#napoleon#napoleon's marshals#italy1814#italy1815#naples#king joachim of naples

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Helfert, “Joachim Murat”, Chapter 4, Part 5

We left Murat after the defeat of Tolentino and now have a look at what was going on with the other King of the Two Sicilies, the one actually sitting in Sicily, Ferdinand.

Among the motives that led Joachim to consider a speedy retreat to Naples was the impending danger from Sicily.

There were still British garrisons on the island, and Ferdinand IV himself desired it, although he was almost constantly at odds with their leaders, and especially with England's diplomatic representative. A'Court was full of complaints about him. "The foundations of the constitution," he had written to Castlereagh on January 5, 1815, "or rather I should say its rhymes, for it has never had any foundations, are being swept out of the way on all sides, and it appears as if, as soon as Naples is won again, everything will revert to a mild despotism, or else, if the court does not succeed in this, will take on a strictly aristocratic character and make the already overconfident barons fully masters of the king as well as of the people." The parliament had recently convened on October 22, 1814, and had been in session for months into 1815, constantly preoccupied with the financial question, which it had been unable to resolve satisfactorily. There had been some of the most heated exchanges; one day towards the end of January, the deputies literally got into each other's hair, so that the guards had to intervene to break them up. When the English had cancelled the King's subsidies of 400,000 pounds sterling annually, which were to be discontinued on 1 March, the matter had become so urgent that Ferdinand IV had had to resort to an extraordinary measure, which, as we remember, was taken on both sides of the Faro at times of need. By royal decree of 18 February, until the parliament had succeeded in restoring financial order, the salaries of all civil servants and officers due at the end of the month had been suspended, which not only exposed the majority of those initially affected to bitter shortages and worries, but in its further consequences also had a terrible effect on public safety; hardly a night went by in Palermo without houses being broken into, the inhabitants robbed, everything that could be carried away stolen, so that all better-off families were in constant fear of their lives. But all these sufferings and worries now took a back seat to the greater events taking place on the mainland, which were bound to change the situation on the island.

On April 29th, an alliance treaty was concluded in Vienna between Austria, with the accession of Russia and Prussia on the one hand, and the Court of Palermo on the other, by virtue of which the latter, represented by Prince Leopold and Commander Ruffo, undertook to put 30,000 men into the field and to bear all the costs of the campaign. In the second article, the conditions were expressed under which Ferdinand was to take over the government of Naples again: no investigation and persecution, recognition of the sale of state property, guarantee of public debt, keeping the new (Buonapartist) nobility on an equal footing with the old, and generally maintaining all the honours, promotions and pensions conferred by the previous governments. On the evening of May 4, the Prince and the Minister departed from Vienna, and from that moment there was no longer a "King Joachim", no longer a "Queen Caroline", but only a "Mme Murat", a "Marshal Murat", of whom Castlereagh said in the British Parliament that he owed his fall only to the ambiguity of his attitude: "if his sentiments could have been relied upon, he would not have been deprived of his crown". In Bianchi's main quarters, in accordance with the instructions received from Vienna, the royal title was still maintained; only Lord Burghersh, following the example of his compatriot Bentinck, did not allow himself to be deprived of speaking of anything other than "Marshal Murat", even in official dispatches.

On April 30, the day after the Treaty of Vienna, of which Palermo was of course not yet aware, the king announced his imminent departure for Naples in a solemn parliamentary session and demanded the necessary means, which the Estates willingly provided. To his Neapolitans, however, Ferdinand issued a manifesto, dated May 1st, which his supporters were to smuggle in and distribute in both Calabria and the other provinces as well as in the capital. Mistakes that had been made were deplored without any intention of punishing them; peace and harmony, general forgiveness and forgetting, the retention of all civil servants and officers in their ranks were promised; laws were envisaged that would serve as a basis for future state institutions and as a guarantee of civil liberties. Ferdinand did not wish to wait for the final outcome of the war before preparing to sail to Naples; he decided to go to Messina for the time being in order to be closer to the development of events.

A British fleet of 20 warships of various sizes under Admiral Bellew sailed in the Tyrrhenian Sea and kept an eye on the coasts of the mainland.

In Naples, after the first unfavourable news had arrived in April, extensive precautions had been taken to put the capital and Capua in a state of defence, especially Gaëta, where a whole suburb was razed, all the inhabitants who did not know how to provide themselves with food for months were expelled from the city, and the government palace was prepared to receive the royal family. But all these measures, initiated with strength and prudence under the rule of the regent, could no longer help a cause which made the rampant licentiousness in the ranks of the army appear to be already lost.

On May 4, after the second day of the battle of Tolentino, the general retreat of the royals had begun, more sinister than the previous defeat. The Carafa brigade disobeyed its commander and the soldiers ran in groups towards the Neapolitan frontier. General Lecchi had to report to the king that he was no longer able to keep his soldiers in obedience; the situation was no better with the legion of the wounded d'Ambrosio; Carascosa alone led his "legion" back in good order. The closer they came to the borders of their homeland, the more numerous the deserters became. The onset of severe frost, "not like in the Italian spring but like in the gruesome winter of Switzerland", as Colletta puts it, plus heavy rain that drove all the water over the banks and thus caused stagnation in the columns, were as much occasions as cloaks for the desertion. With bitter sorrow, the king saw such a beautiful army, his pride and his joy, disappear before his eyes, dissolve into its components; his otherwise cheerful countenance, smiling happily for everyone approaching, was now darkened by heavy grief and large tears streamed from his eyes down his cheeks. It was at the passage over the Tronto, at the border of his kingdom, which he was to cross again as a defeated man, where the word "abdicate" was spoken before him for the first time. In the first surge of his anger he wanted to strike down with his own hand the general d'Aquine, who had hitherto always played the humble servant; but he restrained himself and merely relieved him of the command which he had not held with great glory. The king, for his own part, even in this ignominious retreat, often performed miracles of valour. General Colletta relates an instance in which the king, who was brave to the last moment and the last in the train, helped with his own hand to barricade a road at the entrance of which a detachment of Austrian cavalry was charging and firing. But Joachim could not be everywhere, and where he was not, there was nothing but disaster. The imperials made one capture after another. At Lanciano, 23 cannons, 10 howitzers, 20 ammunition carts and their crew fell into their hands. Manhès, who was only strong when he was raging, abandoned his position at the Garigliano, the important border river, on 6 May, without having seen anything of the enemy, so that the Queen relieved him of his command and persuaded the Minister of War to take his place in the field. On May 10, Joachim was in Bopoli, on the 11th he held a review of his troops; he still had 14,000 men with 16 guns. But already the apostasy in the provinces began to spread, which also had an effect on the ranks of the army. In those days, an appeal arrived from Isernia from the sub-intendant Milizia, in which the soldiers were called upon to abandon Murat's cause. When the king heard of this he exclaimed painfully, "And I, who have done nothing but good to this man!" He made a last attempt to retain the loyalty of his people and sent the General and State Councillor Colletta to the capital, where, together with Minister Zurlo, he was to draft the outlines of a constitutional charter; but Joachim urged them not to be too generous with the concessions to the people.

#joachim murat#caroline murat#naples#naples1815#ferdinand de bourbon#napoleon#helfert murat#italy1815

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Helfert, Joachim Murat, Chapter 3, Part 2

(We left Murat claiming to British visitors that he, despite wanting Napoleon to drive the Bourbons out of France, was still totally in the Alies' camp.)

In spite of these assurances, everyone now knew very well what to expect from his side. Moreover, the facts were in stark contradiction with his words. All kinds of armaments were brought to completion with restless haste, throughout the kingdom the press of sailors was ordered to man the vessels; the royal guards, all troops were ordered to be ready to march; his aides-de-camp were constantly on the move in this or that direction. A year earlier Joachim had already begun to give the civil militia a better establishment, this was now continued most assiduously. The capital also received a military guardia di sicurezza, six battalions on foot and an escadron; property and the intelligentsia formed the elements drawn to their service: the wealthy privateers, merchants and tradesmen, professors, civil servants of all grades; a special medal of merit with the motto: "Onore e fedeltà" was created to stimulate their zeal. Ever since the world peace had been concluded, and with explicit reference to this change, Joachim had also tried to create a Sicilian regiment, Neapolitans who had followed Ferdinand IV to the island, but for whom there was now, as Murat thought, no longer any reason to stay abroad; but the influx was very small, the intended regiment never came into being. Among the officers' corps, a very dangerous increase consisted of many Lombards and Romagnoles who had formerly served in the army of the Kingdom of Italy and who, according to the custom of such fugitives from the country, had their mouths full of lofty words, pushed for an immediate upsurge in arms, which would be met with the most brilliant successes: old comrades would flock to them from all parts of Italy, hundreds, thousands of them armed and uniformed, gladly joining the King's army.

These military precautions went hand in hand with some personnel changes in the upper circles of government. The Minister of Finance, Mosbourg, a Frenchman by birth, asked for and received his dismissal - he had made his penny dry and did not want to expose it again to all the storms and rigours of the weather; he became Secretary of State in place of Prince Pignatelli-Cerchiara, who took over the vice-presidency of the Council of State from Cianciulli. The portfolio of finances was given to Baron Nolli, who had to begin his office with the most hateful measures: the merchant class was hit with a compulsory loan of 2 million francs; all the coffers, not excluding those of the hospitals and charitable foundations, were emptied to the last penny. Maghella was once again put in charge of the police; General Manhès became the governor of the capital, two personalities whose very names were disgusting to the people.

The author here in a footnote quotes Mier from a letter of 12 March: "Ces deux individus jouissent de la plus mauvaise réputation et sont détestés comme étrangers".

Under these circumstances, Mier's position in Naples became a very unpleasant one, and he urgently begged Prince Metternich "not to forget him". In the face of Joachim's assertion and that of his organs, in particular the government newspaper, maintaining that the King was in full harmony with Austria, that his policy was also that of Austria, Mier took every opportunity to loudly contradict this: "Austria is rather resolutely opposed to having the peace of Italy disturbed; the King, by pursuing his warlike desires and a delusion of greatness, will drag himself and his own to ruin". He sent a confidential letter to the queen, imploring her to do everything in her power to prevent her husband from making a hasty decision. He had discussions with Gallo, to whom he gave his unreserved opinion and drew his attention to the fact that the first step taken by a Neapolitan soldier across the demarcation line agreed on 28 April at Bologna would have the immediate consequence of breaking the Austrian alliance.

As early as the 12th of March it was said that the King would leave for the army, Mosbourg and Zurlo with him, Gallo and Macdonald to follow, and the Duke of Carignano to conduct foreign affairs in the meantime. The Princess of Wales, on hearing this decision, had offered to precede the King to Ancona; but he had sent her his regrets through the Duke of Roccaromana that he would not be able to receive her there, whereupon she angrily departed that very morning for Civita Vecchia, and from thence to Genoa. But the king's departure did not come to pass for the time being. Once again, doubts had intervened: repeated and strong hints from the Austrian envoy, requests and ideas from the queen, insistent advice from serious men who were in Joachim's confidence [footnote see below, as somewhat longer]. For a moment it had seemed as if everything was to be reversed, regiments that were about to march had been ordered to halt, others had even said that they would be recalled from the Marches.

Then new favourable news arrived of Napoleon's advance in France - from the evening of 10 March, when he entered Lyon, which might have been reported in Naples on the 15th - and now there was no more rest and no more peace for Joachim. He hastily summoned the Council of State, which was attended by the Queen, all the ministers, and the top generals, not to hear the opinion of those present, but to win them over to his own, which he did with all the grandiloquent exuberance of a Gascogner: 8,000 of his own troops, 14 battalions of provincial militia, civic militia without number; in addition, appeals from all parts of the peninsula, here a letter speaking of 12 regiments in readiness, of 12,000 shotguns in stock, there a letter with the promise of four fully equipped regiments, another promising the whole mass of the disbanded Italian army. The majority of those assembled listened to these reckless reports in incredulous distrust; with regret they saw the King's self-deception, and urgently advised against a hasty step: "one should rather await the answers from Vienna and London, the last success of Napoleon's enterprise, the resolutions of the Congress of Vienna on this unexpected change of affairs". Joachim suspended the meeting without passing a resolution that he did not like, sent Count Beaufremont to France with the declaration that the Emperor could count on his services, and let the Roman Court know through Cardinal Fesch that he regarded Napoleon's cause as his own and soon intended to prove to the world that it had never been alien to him.

On the evening of March 15, the Austrian envoy had a conversation with the Duca di Gallo, the contents of which left no further doubt. Joachim's minister complained about the obvious cooling in Austrian sympathies; about the neglect of his monarch's interests on the part of the Viennese Cabinet; about the small amount of effort the Cabinet had made to obtain the king's recognition from the other powers; about the humiliating way in which the king's ministers and other trusted individuals sent there by him were treated in Vienna. "The Congress will come to an end," Gallo concluded, "and Austria will not have fulfilled the promise she made to us. From this we can conclude no other than that she will abandon us in an extreme case, from which it further follows that the King must seek assistance where it is offered and resort to those means which he can hope will help him to his goal...". The next day, Mier appeared before the queen, who, as she complained to him, had been brought completely down by her sorrow, as well as by the continual quarrelling and disputes. "The King thinks," she said, "that Napoleon's successes will help to keep him on the throne. You know my opinion on this point. I will not cease to advise him that if the Vienna Cabinet should decide to oppose Napoleon, there is nothing left for him but to join Austria and follow her system and policy. You see, I am sacrificing my personal feelings and the agony of seeing my family persecuted, covered with shame and reproaches, to the duties of a mother, to the duties of a Queen of Naples. Emperor Francis has remained our loyal ally until this moment, and I am convinced that he will continue to do so in the future, if we know how to deserve it. This is his duty: but his own best interests also require him to do so".

[Footnote] Among them, in the first row, Pietro Colletta who, on March 11, "in his capacity as Councillor of State", sent a letter to the King urging him against any daring enterprise. The unification of Italy was a dream, "un filone di uomini caldi si abbandonerà a questa idea lusinghiera, ma la massa degl' italiani o la spregerà o la riguarderà con indifferenza o si armerà contro di essa". Twenty-five years of war and revolution had created a deep need for peace; the fine phrases used to flatter the passions of the people had lost their power. And how much preparation was needed to bring the war power up to the proper level! "L'armata di V. M. potrebbe esser battuta prima che aiutata!" The King should keep calm, so that time would pass which would only benefit the existence of his dynasty ... F. Palermo who published the letter in Arch. stor. ital. 1856 III p. 62-65, declares himself unable to state whether the letter really reached the king's hand or not.

Okay, this seems huge to me. I had no idea how much Joachim had suffered from being branded a traitor and how much it had weighed on his conscience. "[...] he regarded Napoleon's cause as his own and soon intended to prove to the world that it had never been alien to him." I guess the need to prove to both himself and to the world that he was not a dishonourable being played a huge role in his disastrous decision. (This actually reminds me of a dissertation on Austrian general Mack - the one from the campaign of 1805 - that claimed that similar mental stress led to the latter's irrational behaviour during the time auf Ulm.)

"Onore e fedeltà" may actually be a direct reference to Eugène's (at the time often quoted) proclamation to the people in the Kingdom of Italy, dated February 1, 1814, which publically announced Murat's defection and declared the Neapolitans an enemy to Napoleon's cause. ("Français! Italiens! j'ai confiance en vous; comptez aussi sur moi! Vous y trouverez toujours votre avantage et votre gloire. Soldats! ma devise est Honneur et Fidelité! Qu'elle soit aussi la vôtre; avec elle et l'aide de Dieu nous triompherons enfin de nos ennemis.") Murat basically claims that phrase - that had been directed against him - back.

Naturally I'm also interested in those "fugitives" from Lombardy who had come to Naples and may have presented a highly misleading picture of people's attitude in Northern Italy at the time. In truth, the different political factions there seem to have agreed pretty soon in their dislike of their new Austrian masters (I believe it is in August 1814, only four months after taking over, that Bellegarde has to send military to the Scala of Milan because riots were about to break out) but that does not necessarily mean they were friendly towards the Neapolitans - who by most were considered as foreigners just as much as the French had been. Also, the Austrians seem to have taken immediate measures to remove all rebellious elements from the country; I believe it is Méneval who mentions how all the Lombardian officers suspicious of still being too attached to the old regime, were transferred to Hungary and, on their way there during the Congress in Vienna, stopped by one by one to see their old viceroy. And to probably reproach him for not having marched on Milan in April when the riots broke out.

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mier's letters from Naples, mid-March 1815

Things are starting to fall apart.

Mier to the Duke di Gallo (Copy)

Naples 12 March 1815 (morning).

The departure of His Majesty the King, announced as very near, for Ancona, the movement almost general of Neapolitan troops from the interior towards the frontiers of the Kingdom, the order given to the Royal Guard to be ready to march, and many other circumstances and measures taken, prove only too well that His Neapolitan Majesty has projects in view which it is important for Austria, friendly power of the King, to clear up, principally in the present circumstances.

The undersigned Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary of His Majesty the Emperor of Austria to the Court of Naples therefore has the honour of addressing His Excellency the Duke of Gallo, Minister of Foreign Relations, in order to obtain from His Excellency prompt and categorial clarifications and answers in this respect, so that they can be brought to the attention of his Court as soon as possible.

In requesting His Excellency to send him His reply today to be sent by a courier which he is sending tonight to Rome, he has the honour to renew to Him on this occasion etc.

(Signed) Mier. To His Excellency the Duke of Gallo etc.

That sounds a lot like a diplomatic ultimatum. And I can't help but be reminded of the letter Eugène wrote to Murat the year before ("So ... you with us or against us, buddy?")

Mier to Metternich. Postscript

Naples, March 12, 1815, evening.

My Prince!

1) The greater part of the garrison of Naples set out this morning. The few troops which still remained will start tomorrow. Veterans and invalids have occupied all the posts. The officer carrying my present expedition will be able to verify in his journey the number of those who have taken the road to Rome, and will report to Marl Bellegarde; all the rest of the garrison and the troops of the surroundings will have marched towards Ancona. The field crews, the King's treasury, and many people, both civil and military, attached to his person, are leaving tomorrow. Everything proves that the King has made up his mind and that He is only waiting for the first news of Napoleon's enterprise to act. I do not believe that He has the project to march into France. He will try to raise Italy and take possession of it; it will be necessary therefore that He fights with us. Although one wants to make believe that these steps are concerted with Austria, consternation is general here, people distrust the King's head and foresee misfortunes.

2) This morning there was a Circle at Court; several Englishmen attended to take leave of the King. He gave them a long speech on the recent event that occupies all minds. He said that he had news of the Emperor from Grasse; that everywhere he was received with enthusiasm and that there was no doubt that he would succeed in his enterprise; that he could not but ardently desire it, the Bourbons having declared themselves openly his enemies in spite of all the steps and advances he had made to render himself sympathetic; any change of dynasty in France could only be advantageous to his interests; that it would be quite indifferent to Him whether it were Napoleon or some other French general who occupied the throne of France, provided it were not the Bourbons: "I am their enemy, as they are mine". He said that he marched his troops towards the frontiers to be more in touch with events; that moreover his policy remained invariably attached to that of Austria; ... and much other drivel which relates to his military career and his elevation to the throne of Naples.

3) The Princess of Wales left this morning for Rome, from where she intends to go to Civitavecchia and embark for Genoa on the English frigate which had come to Naples to fetch her. She wanted to follow the King to Ancona, but yesterday morning he had his Grand Equerry tell her that the political situation prevented him from receiving her in Ancona. It is said that she was furious and decided to go to Genoa.

4) As the Duke of Gallo has not yet sent me an answer to my note of this morning, and seeing the urgent need for Your Highness, and Mar Bellegarde to whom I am writing at the same time, to be informed of what is being prepared here, I have decided to send my mail to Rome without waiting for this answer, which I will send to Your Highness as soon as I have received it.

5) My position here is becoming very embarrassing and I beg Your Highness not to forget me and to give me His orders as soon as possible.

6) I have the honour of sending herewith to Your Highness the two proclamations of Napoleon to his army in France. I have the honour etc.

Mier.

The proclamations are not cited but according to the author, vary only in details from those in Napoleon's correspondence. Mier actually even received Gallo's reply before sending off this letter to Metternich.

Gallo to Mier

Naples, this 14th of March 1815.

My Lord Count! Having had the honor to submit to the King the note dated the day before yesterday which you did me the honor to address to me: S. M. could not read without surprise that you show concern about the march of His troops towards the frontier when it is known that France gathers considerable forces in Grenoble and Dijon with hostile aims against the King, as the Cabinet of Vienna itself is convinced.

In addition, the extraordinary and unexpected events which are taking place at this moment and which can set the continent ablaze again, are of such a nature as to require that the King be in a position to act for his own preservation, and as a result of the answers which His Majesty impatiently awaits to the overtures which His ministers have been ordered to make to the Cabinet of Vienna.

I have already had the honour of speaking to you about these overtures, as well as about the journey of His Majesty into the provinces and countries occupied by His troops, a journey which was decided upon and announced, as you know, My Lord Count, at the beginning of the winter.

I have no doubt, My Lord Count, that you will find in these clarifications very natural motives for justifying the movements in question.

Please accept the repeated expression of my highest consideration

The Duke of Gallo.

I'm not sure if di Gallo actually expected Mier to believe this.

Mier to Metternich, Postscript

Naples, March 16, 1815.

My Prince!

1) Today at three o'clock in the afternoon I received an invitation from Her Majesty the Queen to come and see her. I hastened to go and found Her Majesty very distressed. The King had just received a letter from Florence from General Pignatelli announcing the arrest of Madame Mère and Princess Pauline by the Commander of our troops at Villa Reggio [correct: Viareggio]; that they were being treated there as state criminals; that one of our officers was always keeping watch over them. The Queen told me that this news had enraged the King, and that she was very saddened by it. I tried to reassure her that there was surely some exaggeration in this report; that I supposed that these ladies having landed at Villa Reggio, the Governor of the Principality of Lucca would have thought it necessary, in the present circumstances, to oblige them to remain there until he received orders concerning them from the Marshal, the Count of Bellegarde; that everyone in his place would have done the same; that moreover I could assure her that these ladies would not be mistreated. The Queen informed me that the King had sent General Filangieri to Marshal Bellegarde to urge him not to oppose the continuation of the journey of these two Princesses to Naples, and that he had charged her to ask me in his name to support this request. I replied that I would do so willingly and that I would take advantage of General Filangieri's departure to write to General Bellegarde, as I did indeed as soon as I got home, and I had my letter delivered to the Queen's Cabinet. This evening Mr. de Gallo gave me the attached note, which I have the honour of bringing to the attention of Your Highness. I confined myself to acknowledging its receipt and to informing him that I had already written on this subject to Marshal Bellegarde at the invitation of Her Majesty the Queen. She must also have addressed His Imperial Highness the Grand Duke of Tuscany to ask him to take an interest in this matter and to try to arrange it in accordance with their request.

The note Mier refers to is not cited, but seems to have repeated Caroline's protest against the way Letizia and Pauline had been treated.

2) I found the Queen very distressed and dismayed at all the King's actions. She repeated to me what she had already told me in this respect, and assured me that she was doing everything in the world to prevent the King's departure, because she foresaw the consequences; that twice in succession he was about to get into a carriage to leave Naples and that she had succeeded in diverting him from it; that in order to persuade Him to give up this journey She had declared to Him that She did not wish to take charge of the regency, or to interfere in any way whatsoever with the affairs of the government in His absence; that if He left She would retire to Portici to live there in the greatest seclusion, and that She did not wish to receive any minister there, and much less to talk to him about business. This statement greatly embarrassed the King; for He knew that in His absence no one was in a position to conduct business but the Queen.

3) She told me how the notes which Your Highness had addressed on February 26th to Campochiaro and on the 25th to Talleyrand had had a bad effect on the King's mind; that in them there was no question of defending the King, but rather the Princes of the House of Austria; that the King believed himself to be on the eve of being sacrificed by our Court. He claims that we have been sparing Him and lulling Him into hope until the moment of a definitive arrangement with the other powers, and that we are now gathering troops in Italy to dictate to Him the rules. The Queen told me that She was far from admitting his ideas, having too high an opinion of the loyalty of the Emperor Francis, but that with the distrustful character of the King it could not be put out of His mind; that these ideas and the appearance of the Emperor Napoleon on the scene at the moment when He believes Himself sacrificed, have turned His head. "He believes that Napoleon's possible successes may help to keep Him on the throne of Naples. You know," she continued, "my opinion in this respect; I do more; I advise the King that if Austria replies that she is determined to oppose the possible successes of the Emperor Napoleon, He should join her, and follow in everything her system and policy. You see that my particular affections and the torment of seeing my family persecuted and covered with disgrace give way to the duties of a mother and those of a Queen of Naples. The King must hold on to a great power which protects Him; if He ventures to fly on His own wings He is lost. I once held to the system of France to the last extremity, because I was convinced that our interests required it. Events have had to change our policy; I have convinced myself that our salvation depends on our intimate union with Austria, and I hold to it with my heart and soul. The Emperor Francis has supported us until now as a loyal ally, and I am sure that He will not abandon us, if we deserve it. It is His duty, His own interests command it." I replied that this was an excellent response. I observed to Her that Austria could not be satisfied with the conduct of the King, mainly in what relates to our Italian provinces and to the affair of the Marches. She tried to defend Him and contradicted several statements I had made in support of my thesis. "But the King's last steps," I said to her, "can only increase our distrust and discontent?" "I fear," she replied, "that they will produce this effect; you know how much I have fought against them; but do not look for much malice in them; it is a spur-of-the-moment move, a foolishness which is repeated and which I hope will not be supported. The King is calmer, more reasonable, and I flatter myself that this state of affairs will continue." She could hardly speak, so weak was she. "You see", she said to me, "in what state my sorrows and the continual debates I have to support have reduced me, I often lose courage. I observed to Her that She would make a well-deserved reproach to herself all her life if at such a decisive moment She allowed herself to become depressed and discouraged, and did not use all her power to prevent false steps. May Your Highness please accept etc.

Mier.

Sort of typical: So the boys made a mess of things, and the one woman around is supposed to reproach herself for not having prevented it.

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Letters from Naples, 1815

Some documents relating to chapter 3 of Helfert's book on Joachim Murat. I have not translated the report by Pauline Bonaparte's secretary about Napoleon's escape that Mier refers to in his second letter, as it's quite long and I assume it's been translated and quoted before. But I can do so if there is interest. Mier's letters however, are about Murat's immediate reaction to this news.

Mier to Metternich (in his own hand). (N° 21)

This 5th of March 1815.

My Prince! His Majesty the King received this morning a letter from Rome with the news of the escape of the Emperor Napoleon from the island of Elba. The Chevalier de Lebzeltern took advantage of this opportunity to announce this same event to me. Your Highness can easily imagine the effect which this news produced on the minds of Their Majesties. - The King sent for me to come to him to talk to me about this event, and told me that in a few hours he would send a courier to Vienna. Campochiaro was ordered to declare to our Court that in any event the policy of the King of Naples remained entirely subordinate to ours, that nothing could make Him deviate from this principle, and that He wished to know what course we would believe necessary to follow in this affair in order to comply with it. The King repeated to me on this occasion how much he wished to give the Emperor Francis proof of His attachment and His gratitude.

While we were talking we saw several merchant ships enter the port. His Majesty sent to find out where they came from. It turned out that one of these ships had come from the island of Elba and had left after the flight of the Emperor Napoleon. The captain of this vessel gave the King details of which we were unaware, and communicated to Him the proclamation of the Governor of the Isle of Elba after the departure of Napoleon.

May Your Highness deign to accept the assurance of my highest consideration.

Mier.

Mier to Metternich. (N° 22)

Naples 9 March 1815.

My Prince!

1) The departure for Rome of two officers of our Regiment of Prince-Regent Houzards, who have spent a few days here, provides me with a sure occasion to send my following dispatch to Rome and to recommend it to the care of the Chevalier de Lebzeltern.

2) It is only the day after I sent my report No. 21, that I learned that on the ship arriving from the Isle of Elba there was a certain Mr. Mary, secretary to the Princess Pauline. It is from him that all the details of Napoleon's escape were obtained. I do not believe that he brought letters for Their Majesties, at least the Queen has very definitely assured me of this. She has been kind enough to send me the attached document, written by Monsieur Mary.

3) I had the honour of informing Your Highness in my last report that I had been called to the King's residence at the moment when he had received the news of Napoleon's departure from the Isle of Elba. I found the King extremely agitated, not knowing where to stop his thoughts. It was obvious that he did not know what to desire. He maintained that the Emperor Napoleon landing in France would have the entire army, the whole of France behind him; that the Bourbons would be driven out; that Napoleon would not have risked this enterprise without being semi-certain of its success; that if he found a very doubtful party of the Bourbons resisting him, it would bring on a civil war in France. "What side will Austria and the other Powers take? It is a very unfortunate event, and one which may confuse all at the moment when the main questions had been happily arranged at the Congress. It is no less unfortunate for me in many respects: it may delay the arrangement of my interests, and in the long run I cannot remain in this position; I must know where I stand." He would go out at any moment to ask for news of the ships entering the harbour. After a conversation of more than two hours in the presence of the Queen, he withdrew when a ship from the island of Elba was announced. Afterwards I had a long conversation with the Queen who always consistent in her way of considering things, wise in her views and reasonings, putting character and perseverance in the party and the course which she once convinced herself was useful to her interests, not varying opinion at any event, always preaching uprightness and loyalty, gave me on this occasion new proofs of the essential qualities which distinguish her. One could see in her face how much this event had upset her. She told me that she was extremely worried about the fate of her brother, who was running towards his inevitable loss; that as a sister she could not wish for his death, but that she would have liked him to keep quiet in Elba; that she was convinced that, if the Emperor Napoleon ever succeeded in replacing himself on the throne of France, he would hasten to chase them out of Naples, a thing she never ceased to repeat to the King; that the Emperor Napoleon, once again Emperor of the French, will once more upset the whole of Europe; that she knows his character too well to ever doubt it; that it would be wrong to believe that age and experience have corrected him. "The King", she continued, "has a fine role to play, it is to remain invariably attached to the policy which he has embraced, to unite his interests as closely as possible with those of Austria, to repel all the perfidious insinuations which will not fail to be made to him, and to remain firm in his promises and declarations. This is what his honour and his true interests demand. You know me too well to doubt that I will not do everything to this end.

4) A Neapolitan courier sent to London carried the same declarations as the one that left for Vienna. The same day that the news of Napoleon's escape was learned here, the King convened an extraordinary Council of Ministers in which he declared to them that this event would in no way change the course of his policy. Notwithstanding these declarations and promises made to his people and his Allies, I know that his head is hard at work; that he has admitted into his presence several French refugees in Naples, enraged Bonapartists; that he has had several conferences with them; that he has sent secret emissaries everywhere (I have pointed out to Marshal Bellegarde two of this number who are on their way to France by way of Milan), and that his announced determinations are very shaky. This event instead of delaying his planned journey to the Marches seems to have accelerated it. His saddle horses and some campaign crews left last Monday for the Marches. His departure may take place at any moment. His mood, his words announce that he has projects in view, but that his ideas are not yet fixed, and that he is waiting for the first results of Napoleon's enterprise. If He remained in Naples, surrounded by the Queen and by a few sensible people who, without flattering Him, have the courage to tell Him the truth, one could count on His not being drawn into a few false steps; but in Ancona, returned to himself, surrounded by hotheads, there is nothing to be sure of. I have done everything to prevent this journey, I have begged and insisted that it should not be undertaken at this time, because of the bad effect it would have, and the suspicion that He would arouse by this step. I know that the Queen, Monsieur de Gallo, the Count of Mosbourg and many other reasonable people have positively advised Him against it; but all in vain; He seems determined to go. It is not yet known whether He will leave the Regency to the Queen.

5) Spirits in Naples are very agitated. There are people who make wishes for Napoleon, without knowing what they are asking for; but in general one would be angry here if the King interfered in an affair foreign for the moment to the interests of this country, and in despair if He took up the cause of Napoleon; in the latter case I believe that the King should not count on the fidelity of his subjects. If He wanted to make a diversion in favour of the Emperor Napoleon by going to France, half his army would leave Him; it would not be the same if He remained in Italy. He would find supporters there and could do us a lot of harm. Prudence requires that we put ourselves in this country in a position to face any event.

6) The Princess of Wales has openly expressed much delight at the escape of Napoleon. She told the King that she hoped for his glory that he would not remain an idle spectator of the events that were being prepared; that he should follow the example of the Emperor Napoleon, who with a thousand men despaired of nothing, while he with 80,000 seemed to let himself be imposed upon; that the course he would take in the present circumstances might lead him to immortality, etc. This inconsiderate woman wanted to follow the King to Ancona; but I have just been told that she has changed her plans and that she is leaving for Civitavecchia the day after tomorrow.

7) The Capri, a Neapolitan ship of the line of 80 guns, set sail several days ago to join the two Neapolitan frigates which left for the Adriatic.

8) Until now no movement of Neapolitan troops has taken place in the kingdom.

9) Count Széchényi leaves tomorrow for London. I have endorsed his passport for Rome. May Your Highness accept etc.

Mier.

(Completely unrelated question: What's the legal punishment for throttling a Princess of Wales?) I also love how Mier praises Caroline to Metternich.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Helfert, “Joachim Murat”, Chapter 4, Part 6

Apologies again for taking so long. I always start dragging my feet when I approach the end of a story. The end is usually bad, and I don’t want to see people suffer...

In contrast to the disintegrating Neapolitan army, with heaps of stragglers constantly troubling the population along all the streets and roads, the imperial troops formed a firm stand in closed ranks, with military severity but at the same time with military decorum, and were welcomed everywhere by the inhabitants as liberators. In his pompous appeal from Rimini, Murat had summoned deputies from all the towns and territories of the peninsula to Rome on 8 May, where a national assembly was to decide on the fate and organisation of Italy. That was long over, and instead of the members of the Italian parliament, who had never been expected, the two beautiful Bohemian regiments of Argenteau and Devaur showed up on one of the following days, kindly received by the Romans, and immediately continued their march to the south.

FML Bianchi, now already united with Neipperg's corps, together about 22,000 men strong, moved into the Neapolitan area in four columns. In Aquila on May 12, Neipperg, who had a diplomatic mission in addition to his military one, received a letter from Prince Metternich instructing him to promise Joachim Murat an annual pension of 1,000,000 fl. if he voluntarily abdicated his throne; however, Neipperg should first discuss the matter with the commander-in-chief. The two generals agreed that they would not offer anything to their opponent, for his downfall was certain. That same day, Bianchi issued an appeal to the Neapolitans, proclaiming himself not an enemy but a liberator from the rule of a son of the revolution imposed on them by peace-disturbing France; he promised strict discipline of his troops, respect for the laws and institutions of the country.

"Murat's party is seriously ill; they are trying in vain to bring it back to strength," an eyewitness in Naples wrote on 11 May. On the following day, the queen held a review of the capital's civic guard; she appeared on horseback in Amazon garb with the colours of the guard; she had a graceful word for each of the higher officers; she delighted the ranks, which burst into tumultuous cheers.

But at the same time a British squadron appeared in the Gulf of Naples, whose commander, Captain Robert Campbell, threatened to blow the city into ruins if the forts were not surrendered without delay, along with the "Joachim" and the "Capri", the two new royal ships of the line, and the royal arsenals with everything in them. Abrupt horror replaced the enthusiasm that had scarcely been exhilarated. The Regent called a Council of State, which was also attended by General Colletta, who had just arrived from camp, and Prince Cariati, who had returned from Vienna. The result was, in spite of the grandiloquent proposal of some members to simply reject Sir Campbell's request, that Caroline sent Prince Cariati on board the "Tremendous", where he yielded to all the Commodore's demands, while the latter promised to refrain from any hostility against the capital, to grant the Queen and her family refuge on one of his ships in case of extreme necessity, and moreover to send one of her ministers to Sir Bellew, now Lord Ermouth, or to London, as she wished, to negotiate in the King's name.

The imperial commander-in-chief's proclamation from Aquila had already become known in the capital. The fugitives, runaways and wounded arriving daily in Naples, who could be seen everywhere in the streets, had spread the word and caused a general commotion. Already the Lazzaroni were beginning to stir, and the civic guard was hardly equal to the task of offering them resistance. In a hurry, Jérôme and Cardinal Fesch, Madame Mère and Princess Pauline left the city to embark for France. The Queen said a poignant farewell to her children, whom she had taken to safety in Gaëta. But no one could see what was going on inside her when, on the evening of the 15th, she drove through the streets of the city in a carriage drawn by six magnificent white horses, surrounded by a detachment of mounted national guards in shining hussar uniforms, blue and silver, greeting her on all sides with friendly grace.

On the same May 15, Prince Leopold arrived in Rome and from there sent a letter to Bianchi, expressing to him "his complete impatience" to meet him "at this important moment when the King, my father, will have to thank you for his restoration to the throne of Naples".

The imperial troops advanced ever closer to the kingdom's capital. In the night from the 16th to the 17th, the imperial and royal Major d'Aspre and a small force attacked the camp of the 4th Neapolitan Legion, about 4,000 men, near Mignano and crushed it so completely that by the next morning everything was out of hand and General Macdonald was only able to reach the road three miles further on at Teano without being able to collect the ruins of his corps. When the Queen heard of this blow, she exclaimed: "Macdonald has gone on the scene to bring down the curtain. - Macdonald est allé baisser la toile". After the accident at Mignano, the royal army numbered barely 9,000 men: 1,000 men from the guard on foot, 3,000 from the first legion, 1,200 from the second, about 1,100 from the fourth; then 2,500 horsemen from the guard and line together; there was nothing left of the third division of Lecchi. Carascosa, to whom the king now handed over the supreme command, still held the Volturno line. But on the 18th his vanguard, which had been drawn up at the junction of the roads leading from Rome and Bescara, was attacked by the Austrians and thrown back into the bridgehead of Capua; a few cannon shots fell from the latter on the imperials without doing much damage.

King Joachim had arrived in his capital on the evening of the 18th, accompanied only by four lancers. "Madame", he reportedly said to his wife, "it was not granted to me to die". All his courtiers and supporters in Naples hurried to the palace to show him their devotion, which never made him feel better than at this moment, but which could not change the desperate seriousness of the situation. On the 19th a royal proclamation was issued granting the Neapolitans the long-promised constitution. It was a long document of a hundred or more articles, issued on May 12, backdated by almost a month and a half, from Rimini on March 30. We need not dwell on its provisions, the common phrases of modern constitutionalism; it never became a deed, and it had not the slightest influence on the mood of the minds. At the same time, Murat decided to enter into negotiations with the advancing enemy. On the morning of the 19th, Bianchi was about to mount his horse to inspect the ancient stone arched bridge on the banks of Solipaca, which was to be repaired for the crossing of the Volturno, when the Austrian Consul General of Naples appeared at the outposts. In a country house belonging to the Patrician family of Lanza, three miles from Capua, the imperial commander-in-chief had set up his main quarters, where Gallo soon arrived in the name of Joachim. But Bianchi, who was assisted by Generals Neipperg and Starhemberg and Lord Burghersh, declared that he was not a diplomat but a soldier; that the conquest of the kingdom was as good as complete, that he would neither cease hostilities nor grant an armistice; that there was no longer a "King Joachim", that it could at most be a question of a military convention from which "Marshal Murat" must be excluded. Gallo and the Consul General withdrew, and the military operations continued; during the night of the 19th to the 20th, Starhemberg crossed the Volturno. Then, on May 20, at 8 o'clock in the morning, the generals Carascosa and Colletta appeared at Casa Lanza, where the conclusion of a military convention was discussed, while the imperial troops continued their march across the Volturno at Cancello and Castel-Volturno without interruption. At 4 o'clock in the afternoon the agreement was concluded, signed on the Austrian side by Count Neipperg and the Commander in Chief; Lord Burghersh had taken part in the negotiations without, however, signing his name on the document. There were 13 articles with 6 additional points. According to the first, Capua was to be surrendered the next day, Naples with all its citadels on May 23, and the fortified places of Scylla, Amantea, Reggio, etc., handed over to the allies; only Pescara, Ancona and Gaëta were not included in the convention, because Carascosa and Colletta claimed to be without authority over them. In the supplementary articles, at the request of the Neapolitan negotiators, the Emperor of Austria guaranteed all the provisions which King Ferdinand IV had undertaken to observe on the repossession of his continental territory.

That same evening, after he had learned the arrangements of Casa Lanza, Joachim Murat - thus and not otherwise we may only refer to him henceforth, although no express renunciation of the throne had been made on his part - departed quietly and with few companions, among them his nephew General Bonafour, all dressed as simple private citizens, from Naples, won the beach at Miliscola, near Puzzuoli, and had himself ferried to the small island of Nisita and thence to Ischia, from where, on one of the next days, a merchant ship hired by General Manhès was to take him to France.

Can I start crying already?

#napoleon#joachim murat#caroline murat#naples#italy1815#hundred days#bonaparte family leaving the sinking ship what a clan#metternich still trying to save murat#that's why I don't want to see soldiers in political positions

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Helfert, “Joachim Murat”, Chapter 4, Part 3

Neapolitan retreat, Austrian advance, and preparations for battle on both sides.

On the 12th, Mohr moved from defence to attack and, from the bridgehead at Occhiobello, broke through the Neapolitan position at Ravalle and Casaglia, finding the way to Ferrara open on the 13th. At the same time FML Bianchi advanced to the Panaro, on the 14th to the Secchia, on the 15th forced back General Pepe, commanding in Carascosa's absence, behind the Reno, and on the 16th made his entry into Bologna, which King Joachim had to leave in such haste that he could not collect the war tax he had imposed on the city. At Bologna, where the commander of Lombardy, G. d. C. Baron Frimont, was present, a council of war was held and, against Bianchi's opinion, it was decided that the imperial army should henceforth split and move in two directions towards the south: Count Neipperg on the right wing with 16,000 men and 20 guns along the Adriatic shore, Bianchi with the centre with 12,000 men and 28 guns through Tuscany, to which Nugent, with not quite 3,500 men and 4 guns forming the outermost right wing, was to prepare the way.

King Joachim, apparently soon enough aware of this division of the Austrian army, took his countermeasures without delay.

Again judging from Helfert’s footnotes, he follows Italian writer Colletta in this. According to Pepe, Murat learned much later about it. Helfert seems to be a bit lost between his sources here as Colletta seems to describe events in a much more positive light.

His plan was to retreat slowly from Neipperg and to keep him in sight until Bianchi was separated from him by a long distance, so that one army could not quickly bring help to the other, and then to attack and defeat one after the other, Bianchi first, with his combined superior force.

Sounds like a very Napoleon-like plan.

At the same time he decided to enter the path of negotiation, if only to gain time by stalling. To this end he sent off Legation Councillor Questiаux to his Vienna Congress Legation, April 18, and sent Colonel Carafa as parliamentary to General Neipperg with a letter addressed by his Chief of General Staff Millet to the Imperial Commander-in-Chief, in which he sought to portray the forward movement of his army as a mere security measure, since he was unclear about Austria's intention, April 21. But Questiаux, who arrived in Trieste on the latter day, was not allowed to continue from there, but had to turn back without having achieved anything, and on the 24th Neipperg replied "that the supreme commander had given the most definite instructions to continue the operations with the greatest zeal".

In the course of these days the king, followed at a reasonable distance by Neipperg, had successively evacuated Imola, Faenza, Forli, while in the west his guard legions were retreating from Florence via Arezzo and Perugia towards Foligno. When the Austrians entered Forli, they were told that King Joachim had expressed his intention to fight a battle at Cesena, but then, whatever the outcome, to withdraw within his borders and offer a truce, lest it should appear that he was making common cause with Napoleon.

Uhm... but he had only just received Napoleon’s brother ...? Surely he must have suspected the Austrians to be aware of such communications?

In fact, the Neapolitans under Lecchi's leadership seemed to want to dispute the imperials' passage over the Ronco, which brought about a fierce battle that ended with the retreat of the former behind the Savio. The king, after having deployed in battle formation south of the river at Bertinoro and Cesena, broke camp and in the night of the 22nd to the 23rd retreated via Savignano to Rimini. It was of little comfort to him that here he received a letter from his wife, with a message from his imperial brother-in-law, who was quite delighted with the king's enterprise. But the question was whether Caroline's letter, which Joachim showed around to his generals, was not intended solely to raise the sagging courage of the army, which was retreating from one position to another.

So, Caroline with a fake letter would have supported an enterprise she had so fiercely opposed? I’m confused again.

At Cattolica, on April 26 and 27, the king again seemed to want to engage Neipperg, had entrenchments thrown up in order bring in batteries, but finally changed his mind and went back to Pesaro, Fano, Sinigaglia. His rearguard suffered one defeat after another. On the 28th, already in the darkness, the G.St. Captain Count Thun and Captain Monbach attacked a Neapolitan detachment at Santa-Marina near Pesaro, then entered the city at the same time as the fugitives through the open gate, where Pepe was just having dinner with a friendly family, while Carascosa was already in a deep sleep, caused hopeless confusion among the garrison and, carrying three and a half hundred prisoners with them, withdrew from Pesaro, which the royals now evacuated in a despicable haste.

On the 29th Joachim was in Ancona where he issued an army order to his troops: "the long-awaited moment of battle had come, the previous retreat had been a feint, victory over the Austrians was easy and certain". On the 30th he arrived in Macerata, where the two legions of his guard had already moved in.

FML Bianchi had arrived in Florence on April 20, and with him Grand Duke Ferdinand III. Here, if it had not happened earlier, he was joined by the British envoy to the Court of Tuscany, Lord Burghersh, who from then on remained in his main quarters and, when it came to fighting, was regularly at his side, sometimes intervening himself. On the 23rd Bianchi was in Arezzo, Starhemberg with the advance guard in Cortona on the Tuscan-Roman frontier. Even further ahead, already deep in the Papal States, in Bolsena, Monte-Fiascone and Viterbo, stood Nugent that same day, hurrying in forced marches towards the area of Naples.

In a letter of the 29th, FM Prince Schwarzenberg informed Bianchi that "His Majesty has deigned to transfer to you the command of the army against Naples"; in fact, Bianchi had taken it over even before he had received this communication, because Frimont, called away by other business, hurried back from Pesaro to Lombardy on the 29th. The Vienna Cabinet continued to show the greatest consideration for his opponent. On May 3, Baron Frimont received a letter of order stating that the King of Naples, by his attitude, had given Austria the means to assert the right of conquest against him in the fullest sense. "Nevertheless," it continued, "Murat has been recognised as king by our government, and His Majesty therefore wishes him to be treated as such until the last moment and to be called King Joachim in all negotiations and public writings until further notice." From this letter one can see that on our side, in the higher ranks, modesty and caution set the tone, while the officer and the common man were burning with the joy of battle, as if everything had to succeed. That is the right relationship. The soldier should and, with good leadership, will always consider himself invincible; it is up to the commander not to triumph too soon, to consider all the vicissitudes of the fluctuating fortunes of war. Over in the Neapolitan camp, it was the other way round: great confidence, or at least the appearance of it, on the part of the king and his entourage, wavering confidence, little courage, much unwillingness in the ranks of the army.

Actually, I do read this in a somewhat less friendly manner. This clearly means that, from this moment on, Murat’s removal from the throne was the campaign’s official aim. But let’s remain polite until the last moment.

#joachim murat#caroline murat#napoleon#naples1815#italy1815#1815#hundred days#helfert murat#helfert joachim murat

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Helfert, “Joachim Murat”, Chapter 4, Part 2

We left off when Joachim Murat had just left Naples in order to begin hostilities against the Austrians (or at least that is how they interpreted it).

Around the same time, possibly on the same 31st of March, Count Neipperg left Vienna to guarantee Murat the throne and empire in the name of the allied powers if he joined their alliance unconditionally, and Napoleon sent him a letter in which he informed him of his surprising successes from Lyon to Paris and promised him his strongest help, as he believed he could count on Murat in turn: "Send me an envoy as I will send one to you on a frigate". But while these two different messages were on their way to the king, the die had already been cast, and to Murat's misfortune, at first favourably for him. On April 2, his troops occupied Bologna, which FML Bianchi evacuated with 9000 Austrians. When the troops of the vanguard were called by the city gate guard, the message was: "Italian independence", which was met with enthusiastic cheers from the citizens; at least this is what Guglielmo Pepe reports in his memoirs (I p. 259), which are admittedly an excessively biased source. On the 4th, while the imperial troops, 1000 strong, withdrew into the fortress, the Neapolitans under General d'Ambrosio marched into Ferrara and, under the leadership and personal bravery of their king, forced their way across the Panaro after several hours of hot fighting, a victory which, of course, cost them dearly due to the severe wounding of their brave general Filangieri. Late in the evening, Joachim made his entry into Modena, from where Duke Francis IV had gained Austrian territory in time, while three days later, on 7 April, Generals Livron and Pignatelli captured the capital of Tuscany, which the Grand Ducal family left in flight-like haste. Count Nugent withdrew his force, which was half the size of the Neapolitan forces, to Pistoia, and even there thought himself not secure, so that two British frigates in the port of Livorno had to be ready to receive his baggage and guns in case he could not hold on.

But with this, Murat's cause had also reached the culmination of its successes. An attack he undertook on April 7 against the bridgehead of Occhiobello, defended by the imperial FML Mohr, failed completely. On the 8th, although no heavy artillery was available, he impatiently renewed the attack; six times, disregarding his own person, he led the columns forward to the assault, and each time they were defeated; the enterprise had to be abandoned. Neither did his two Guard legions make any progress on the Arno. Intimidated by false rumours, they advanced only hesitantly against Nugent, pushed back his advance troops by a few miles towards Pistoia, but hardly three days later they again cleared all the points they had won in order to regroup near Florence, April 9 to 13.

At this time Lord Bentinck was in Turin, where he received the news of Murat's departure. On April 5, he wrote to Murat, reproaching him for his breach of faith and denouncing the armistice between Naples and England; on April 7, on hearing that they had already come to blows, he issued an order to all commanders in the Mediterranean to begin hostilities against Naples.

King Joachim was still busy before the fateful bridgehead at Occhiobello, April 9, when he received the letter from his sworn enemy in Turin. He went back to Bologna. Now the safety of his kingdom had to be his first consideration, for attacks from the sea could not be long in coming. In any case, the anticipated surprise of the Austrians, the conquest and breach of their line along the Po, no longer seemed possible. But other things upon which he had intended to build his bright future had also vanished into thin air. It is true that he called all the officers and soldiers of the army of the Kingdom of Italy, who had been discharged the year before, under his banners and promised them the most generous provision for their future, just as he had promised their relatives in the event of their death; he also gave the army an Italian cockade, amaranth and green, April 10.

Amaranth... indeed. I do see a major obstacle for the cause of Italian unification.

But was there any chance that these proclamations would have a better effect than the two previous ones issued from Rimini? The latter had only been laughed at in Rome, where the king had boastfully summoned a general congress from all parts of the peninsula, and in other places there had been no lack of jeers about the call for the unification of all Italians being signed by two Frenchmen, Murat and Millet. Of all the armed troops that had been promised to him, only a battalion of barely 400 men was brought to him by the colonel of the disbanded Italian army, Negri, from the region on the lower Po, where he was at home; Joachim appointed him general on the spot. The lists of volunteers did not want to fill up either. People who had been freed from the prisons where the Austrian administration had put them for common crimes or political charges preferred to return to their families than to put their skins on the line on the battlefields. And the thing that depressed the King's courage more than anything else: were there not Italians under the Austrian banner in arms against him? A Modenese regiment had joined Bianchi, two Tuscan ones had placed themselves under Nugent! In addition to this there was the open response of the Austrian Cabinet to his manifesto of 30 March, in which all his ambiguities, all his aberrations and intrigues were held up to him, all his pompous phrases and promises were exposed in their hollow inanity, which had a downright devastating effect, April 11.

The moral blow was followed by one military blow after another. On April 10 and 11, Bianchi began his advance, attacked Carpi in a storming manner, which General Guglielmo Pepe, after great losses - 600 prisoners, including 12 officers - evacuated, whereupon the king also abandoned Mirandola Modena and Reggio and led his troops back behind the Panaro.

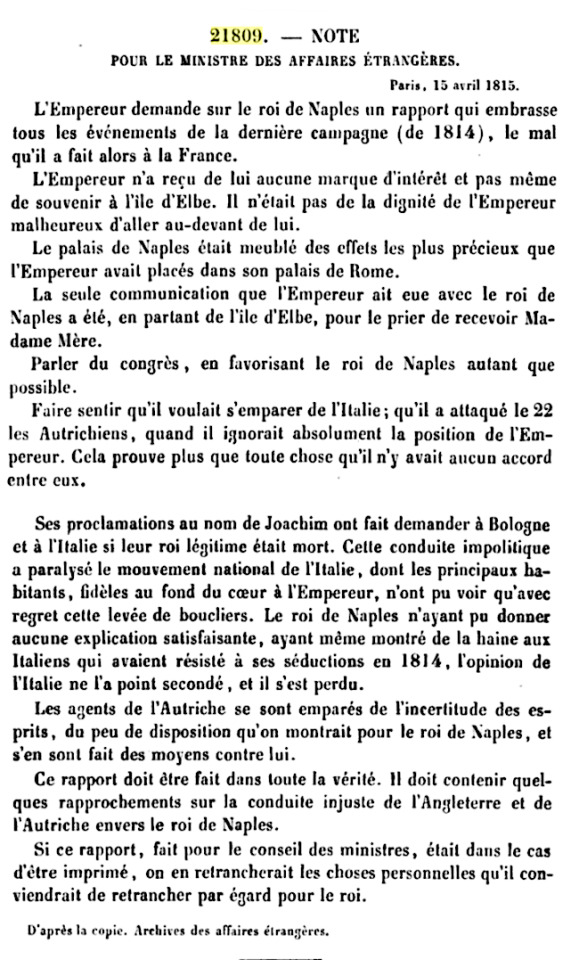

In one of his footnotes stating his sources, Helfert also mentions the report that Napoleon requested from his minister of foreign affairs (Caulaincourt) during the Hundred Days, in Corresp. Nap. XXVIII No. 21809 p. 98 f. of 15 April: a note in which the Minister of Foreign Affairs is ordered to begin a detailed report on the conduct of the King of Naples in the campaign of 1814: "Ce rapport doit être fait dans toute la vérité. Il doit contenir quelques rapprochements sur la conduite injuste de l'Angleterre et de l'Autriche envers le roi de Naples."

I’ve checked this note and made a quick screenshot as it seems quite interesting. Napoleon basically already decrees what the result of the investigation has to be.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Helfert, “Joachim Murat”, Chapter 4, Part 4

The battle of Tolentino

In the last days of April, Bianchi occupied the region of Tolentino, which he examined in person in all directions without delay. He had about 11,000 men at his disposal, while the king faced him with 16,000 infantry and 2,000 horsemen; for the time being, the imperial commander could only think of putting himself in a state of defence, but he decided to hold out until the end. The king had chosen his day well: General Neipperg was only at the Metauro, at four days' march from Bianchi.

At the same time, Nugent was already in the Abruzzi, marching on Antrodoco on 1 May, which General Montigny "cautiously" evacuated with 1600 men, and from there on Aquila, where Major Patrizio with the Neapolitan garrison withdrew to the fortress; but when Nugent earnestly demanded surrender, this was also carried out and the garrison departed with "all military honours". General Manhès had moved from Naples to the Liris with 5000 men and appeared before Ceprano on 2 May. It was certainly desirable for him to find the place occupied by some Roman irregulars, who fired on his invading troops, but then took to their heels; for he could now show his strength, let storm and give rein to the cruelty of his soldiers; part of the little town went up in flames. But Manhès did nothing against Nugent.

On May 1st, Murat and Bianchi faced each other without doing anything, the day passed with mutual observation and reconnaissance.

Nothing happened on the morning of the 2nd either. It was not until noon that the king, seeing that his opponent was determined to stand his ground but not to challenge, gave signal to attack, and that his columns began to move. A cavalry charge, in which Stephan Széchényi, later to become the "Great Hungarian", distinguished himself brilliantly, helped to raise the confidence of the Austrians and shake that of the Neapolitans right at the beginning of the battle. But the fortunes of war fluctuated to and fro throughout the day. An imperial detachment of chasseurs, which had been delayed, was surrounded and captured by royal cavalry. The Neapolitans made progress in detail, ours had to abandon several points to the more numerous enemy, and full of the joy of victory, Joachim sent joyful messages to Naples in the evening. Nevertheless, his army suffered a heavy loss with the wounding of Gen. Lieut. d'Ambrosio.

During the night Joachim gathered reinforcements, especially the Pignatelli-Strongoli legion; he was now almost 25,000 strong. On the 3rd in the morning, dense fog covered the area; when it lifted, the king saw the line of the imperials in a firm position like yesterday, the right wing leaning against the Chienti, the left against a steep mountain, which the Neapolitans considered useless for any gun position: however, Bianchi had used the night to have two cannons and a howitzer disassembled into their parts, brought up and then reassembled and set up again with unspeakable difficulty.

The second day of battle once again opened in the Royalists' favour. FML Mohr conceded Arancia to the enemy who was advancing with superior numbers; a fierce bayonet fight won the Neapolitans the important point of Cassone. But a miscalculated attack by General d'Aquino on La Vedove, used to his advantage by Bianchi at the right moment, inflicted the first serious defeat on the enemy; likewise, an attack by the Maio brigade on the strong position at Vomaccio on the extreme right wing of the imperial forces failed completely. After this it had become noon, a lull occurred, and the battle was at rest for more than an hour. The king decided on a main attack on the hill of Madia on the left wing of the Austrians, which he thought was defended only by small arms. His columns advanced, and the first cartridge shot fell into their ranks, which began to waver in surprise. Now Bianchi ordered the advance. His men seemed to have waited for this sign and rushed to the attack, the phalanges of the dismayed Neapolitans were blown apart; soon the right wing of the royals was struck on the head and dispersed in disorderly flight.

At this fateful moment, the King receives two almost simultaneous bad messages: one from the Minister of War, Macdonald, about the appearance of the enemy on the Liris, the alarming mood in the capital and in several provinces, especially in Calabria; the other from General Montigny about the loss of Antrodoco and Aquila to Nugent. The king is beside himself, orders a court martial against Montigny and Major Patrizio, but this does not help the matter. While he is now thinking of withdrawing his troops from the battle, Bianchi gives him no time to rally. The king's generals lose courage, the men think only of their personal safety; the soldiers, who are not helped by their nimble legs, let themselves be caught in heaps. During the night, d'Aquino and Medici appear before the king with the report that their brigades have been attacked in the darkness, that they have lost many dead and prisoners, and that the rest are scattered; Pignatelli reports that not a single company of his guard is still in order; Livron declares that he can no longer stand for the mounted guard. Not only is the day decided, the campaign is lost, the empire, the throne. Bianchi writes: "The enemy will hardly be able to withstand us in the open field."....

The loss of the Austrians in dead, wounded and prisoners amounted to 27 officers and 795 men, that of the Neapolitans in dead and wounded alone about 1700. 4 adjutants of the king, 3 staff and 35 senior officers, 2219 men were taken prisoner; captured were horses, pieces of armour, 1 cannon, 6 ammunition trolleys, etc.

In a footnote the author mentions two more sources that might be of interest but which I could not find on the spot:

In the Schels'sche Zft. 1819 III [presumably meaning: "Oestreichische militärische Zeitschrift"] there is a map of the battlefield of Tolentino. See also the biography of Bianchi p. 443-458 [I could only find entries in encyclopaedias on Vinzenz von Bianchi]. In later times, ibid. p. 473 note, the commander expressed himself: "The small number that won the victory at Tolentino deserves to be thought worthy of it and contemporaries should not withhold from it the recognition it deserves" ... Orlov-Duvall, p. 185, writes about Mack's unfortunate campaign in 1799: "L'Europe apprit avec étonnement qu'en si pen de temps la plus belle et la plus nombreuse armée qui fût jamais sortie du royaume de Naples avait été battue, dispersée, anéantie". Exactly the same could be said of Murat's campaign in 1815: the destruction did not take place "en si peu de temps", but his army was "plus belle" and "plus nombreuse" than Mack's had been.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Helfert, “Joachim Murat”, Chapter 4, Part 1

Sorry for the long delay!

4. Occchiobello - Tolentino - Casa Lanza.

April/May 1815.

The army led by King Joachim, with which he undertook the great risk of challenging Austria and the Congress of Vienna, did not number 80,000, nor 60,000 men, which were the figures he constantly mentioned, but about 35,000 men on foot and 5,000 on horseback with 60 guns. It was divided into six "legions" - the Napoleonids never lacked ostentatious titles - two of the Guard, of which Pignatelli-Strongoli commanded the infantry, Livron the cavalry; then three line infantry with Carascosa d'Ambrosio and Lecchi as commandants, and one legion cavalry under GL Rosetti. Millet de Villeneuve was at the head of the general staff, and Pietro Colletta, the future historian, was at the head of the general staff.