#prospecttheory

Text

The Dual Forces of Thought: A Review of "Thinking, Fast and Slow" by Daniel Kahneman

The Dual Forces of Thought: A Review of "Thinking, Fast and Slow" by Daniel Kahneman

“Thinking, Fast and Slow” by Daniel Kahneman is a groundbreaking exploration of the two systems that govern human thought processes. The Nobel laureate delves into the realms of fast, intuitive thinking (System 1) and slow, deliberate thinking (System 2), unraveling the complexities of decision-making and cognitive biases that shape our perceptions of the world.

Key Takeaways:

Dual Systems of…

View On WordPress

#BehavioralEconomics#CognitiveBiases#DecisionMaking#DualThinking#HindsightBias#KahnemanInsights#Metacognition#Overconfidence#ProspectTheory

1 note

·

View note

Link

#anchoringbias#behavioraleconomics#behavioralinsights#biasesineconomics#choicearchitecture#cognitivebiases#decisionmaking#economicbehavior#economicdecisions#economicinsights#economicmodels#economicoutcomes#economicstrategies#framingeffect#humanbehavior#lossaversion#nudging#prospecttheory#psychologyandeconomics#rationality

0 notes

Text

Rischio e decisioni di investimento

Contenuto elaborato da: Luigia Barzaghi

La percezione del rischio: dalle teorie normative a quelle descrittive

La decisione è la capacità di valutare e di scegliere, all’interno di un ventaglio di opzioni differenti, quella che possa garantirci il miglior risultato possibile. Alcune decisioni sono facili e rapide da prendere perché le prendiamo spesso, magari quotidianamente, ne conosciamo l’esito e ci sono poche variabili da considerare. Altre sono complesse. In alcuni casi, prendere una decisione è un processo difficile che non si esaurisce in un singolo atto, ma si svolge in un arco di tempo più lungo e richiede l’apporto di competenze cognitive ed emotive. Sono complesse, ad esempio, le decisioni che riguardano i risparmi.

Posto di fronte ad una decisione di investimento, il risparmiatore deve considerare diversi fattori quali: la ricchezza a disposizione, l’orizzonte temporale, il rendimento atteso, il rischio. Il rischio relativo ad un prodotto finanziario è direttamente collegato al suo rendimento atteso: maggiore è il rendimento atteso, maggiore è il rischio. In ambito finanziario, il termine tolleranza al rischio si riferisce alla quantità massima di fluttuazione, di variabilità del valore del portafoglio che un risparmiatore è disposto ad accettare e dipende da molteplici fattori, tra cui il livello di cultura finanziaria, la personalità, la percezione di abilità, lo stato emotivo del momento.

Cos’è il rischio?

“ Il rischio nasce dal non sapere cosa stai facendo ” - Warren Buffett

“ Il più grande rischio è: non prendersi nessun rischio ” - Mark Zuckerberg

Warren Buffett è considerato uno dei più grandi investitori di tutti i tempi. La sua affermazione si basa su una considerevole cultura finanziaria ed un’enorme esperienza. L’affermazione di Zuckerberg si basa su un approccio economico in cui l’assunzione del rischio è una condizione indispensabile per l’imprenditore.

Per una persona conservatrice il rischio può essere identificato col pericolo e, pertanto, nella scelta tra le diverse alternative si concentrerà maggiormente sull’evitamento dei possibili esiti negativi. Una persona ottimista, invece, evidenzierà soprattutto i possibili risultati positivi della situazione decisionale.

Come può essere valutato il rischio secondo le teorie normative e descrittive?

Le teorie normative definiscono la “scelta razionale” che dovrebbe essere compiuta da un “individuo pienamente razionale”: l’homo oeconomicus. Sono teorie elaborate da matematici ed economisti. Nell’approccio alla valutazione del rischio, le teorie normative prevedono l’utilizzo del Valore Atteso (Expected Value - EV). L’EV è il risultato di un calcolo matematico: il decisore moltiplica il valore assoluto di ogni opzione possibile (per esempio, la somma di denaro che potrebbe guadagnare o perdere in un gioco, in una transazione) per la probabilità che l’opzione stessa si verifichi. Secondo le teorie classiche, il decisore, alla fine, dovrebbe scegliere l’opzione con il maggiore Valore Atteso.

Ma ci comportiamo realmente così ogni volta che prendiamo una decisione in condizioni di incertezza? La risposta è no. Ci sono, infatti, delle criticità che ostacolano l’utilizzo dell’EV. Una di queste si riferisce al fatto che l'uso del Valore Atteso è appropriato solo in situazioni decisionali che si incontrano molte volte ed essenzialmente nella stessa forma (esempio: lancio dadi, lotterie).

Grazie agli studi di Bernoulli (1738), ripresi da von Neumann e Morgenstern (1947), un migliore approccio al rischio, da un punto di vista normativo, prevede l’applicazione della teoria dell’Utilità Attesa (Expected Utility Theory - EUT). La formula dell’EUT differisce dalla formula dell’EV per il fatto che il decisore moltiplica la probabilità di accadimento di un evento futuro per il livello di utilità del risultato associato. L’utilità è un fattore soggettivo.La forma della funzione di utilità dipende, quindi, dalla nostra attitudine verso il rischio e, di conseguenza, ciascun individuo ha una differente funzione di utilità: se siamo avversi al rischio, rifiutiamo una scommessa preferendo una quantità di denaro pari al suo valore atteso; se siamo propensi al rischio, accettiamo la scommessa; se siamo neutrali, allora le due opzioni sono indifferenti per noi.

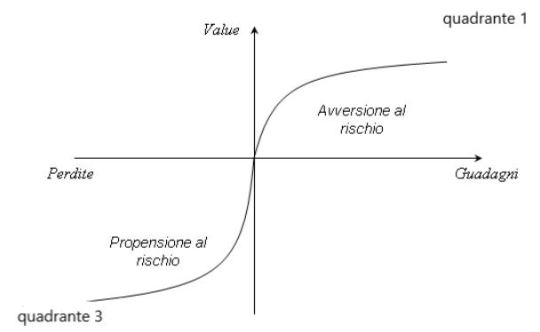

Con la Prospect Theory (PT), elaborata dagli psicologi Kahneman e Tversky nel 1979, entriamo nell’ambito delle teorie descrittive. Mentre il fine della teoria classica è quello di stabilire le condizioni ideali (normative) secondo cui una decisione può essere definita “razionale”, la PT si propone di fornire una descrizione di come gli individui effettivamente si comportano di fronte a una decisione. La PT si focalizza in particolare sulle decisioni in condizione di rischio, che sono definite come le scelte in cui si conosce (o si può stimare) la probabilità associata ai possibili esiti di ogni alternativa a disposizione.

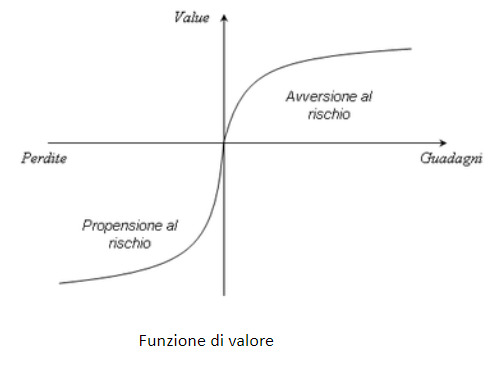

La funzione di utilità viene sostituita dalla funzione di valore. La differenza tra le due sta nel fatto che nella funzione di valore le probabilità degli eventi possibili vengono ponderate attraverso un valore soggettivo che rappresenta il ‘'peso'’ che ogni esito ha nella valutazione dell'individuo. Nella valutazione dell’attitudine al rischio dell’individuo vengono inseriti fattori psicologici: status quo, frame, avversione alle perdite, effetto certezza.

1) Status quo. È il punto di riferimento, di partenza.Nel processo decisionale, non ci limitiamo a considerare come massimizzare la nostra utilità (come sostengono la EV e la EUT), ma confrontiamo le opzioni in gioco in relazione ad un nostro punto di riferimento soggettivo, ovvero il nostro status quo.

2) Frame. Si riferisce al contesto in cui l'individuo si trova ad operare la scelta.Il frame e, in particolare, il modo in cui il problema viene formulato, influisce sul modo in cui l'individuo percepisce il punto di partenza, o status quo, rispetto a cui valutare i possibili esiti delle proprie azioni. A seconda di come vengono “incorniciate” dal punto di vista linguistico, due opzioni identiche possono apparire o come un guadagno o come una perdita rispetto allo status quo.

3) Avversione al rischio nell’ambito dei guadagni e propensione al rischio nell’ambito delle perdite. Per la maggior parte degli individui la motivazione ad evitare un’ulteriore perdita è superiore - di circa 2,5 volte - rispetto alla motivazione a realizzare un guadagno addizionale. Le perdite sono percepite come maggiormente dolorose rispetto delle vincite. Ecco allora la propensione al rischio nell’ambito delle perdite: siamo disposti a rischiare il tutto per tutto pur di evitare un’ulteriore dolorosa perdita.

4) Effetto certezza. Gli individui preferiscono un evento certo ad uno solo probabile.Quando gli individui devono scegliere tra un ventaglio di opzioni che presentano tutte esiti positivi, tendono ad attribuire un peso maggiore agli esiti certi rispetto a quelli probabili, anche se questi ultimi hanno un valore atteso maggiore.

A questo punto, prima di decidere tra diverse opzioni di investimento, soffermiamoci un attimo e testiamo la nostra tolleranza al rischio con il “Risk Tolerance Quiz” (al presente link è possibile trovare una versione tradotta in italiano del quiz con un’analisi del contenuto delle domande. La versione originale del quiz è presente in bibliografia). È infatti preferibile non investire in asset rischiosi se la nostra tolleranza al rischio è minima con la conseguenza di passare notti insonni e provare rammarico e rimorso per la decisione presa. Il test è stato sviluppato, testato e pubblicato nel 1999 da due docenti universitari di Finanza: John Grable e Ruth Lytton. Il Risk Tolerance Quiz è stato ed è ampiamente utilizzato da risparmiatori, consulenti finanziari e ricercatori per valutare la disponibilità ad impegnarsi in un comportamento finanziario rischioso. Non esistono risposte corrette e risposte sbagliate e il profilo che deriva, dalle risposte, non rappresenta un'informazione di per sé sufficiente per decidere se e come investire. Facciamoci consigliare da un consulente finanziario esperto.

BIBLIOGRAFIA:

Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision under Risk. Econometrica, 47(2), 263-292.

Investment Risk Tolerance Quiz (original version)

0 notes

Text

The Cycle of Expectations

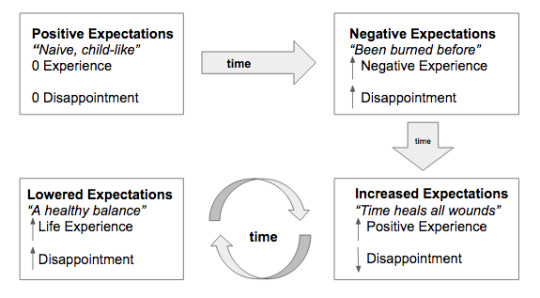

You’re probably wondering why I keep saying it’s necessary to try to have “lowered expectations” and not “no expectations” throughout your life. Well, you’re probably not wondering because no one really cares, but my reasoning is this: I’m not sure it’s possible to actually have zero expectations in any situation and still care enough to put in effort and care. I think it’s necessary to have SOME level of expectation of a situation - otherwise, why would we do anything? We hope to gain something out of everything we do, whether that’s for ourselves, our loved ones, or the greater good of the world.

As a result, I think it’s a life-long cycle to get to a place where you can lower your expectations consistently, so that you are both motivated to move forward in life, but not disappointed when things don’t turn out the way you’d hoped they would, nor are you stuck in the fear that negative expectations usually trigger. I believe that cycle is best illustrated by the following figure:

The four states of expectation shown above are explained in more detail below:

POSITIVE EXPECTATIONS

Early in life, when we’re naive or when we’re new to a situation (say, dating, starting a career, never having lost a loved one), we have extremely (and often unrealistically) positive expectations of the situations we enter into. A good example of this is being a child and being unafraid of heights or getting hurt. When I was younger, I wasn’t afraid of heights, and I rarely feared experiences that could potentially cause me pain, because I had little to no life experience, no true understanding of the consequences, and I had experienced zero disappointment.

This meant that I could climb to the top of a tree, stand on the edge of a cliff, attempt flips over and over on the trampoline, and I wasn’t scared of getting hurt. I had the positive expectation that I could do anything and nothing bad would ever happen to me. I remember my mom used to tell me how envious she was of my fearlessness. She’d say “I used to be like you, so brave! Now, I’m so scared.” I always wondered what happened that made her afraid - at that age, it seemed so easy to me not to be scared.

As I got older, I became more and more scared of everything around me. I’d seen one friend break his arm when he fell out of a tree, another break his leg jumping out of a swing on a swing set, and on my 10th birthday I stapled my own finger, bled and passed out (this hasn’t changed since childhood, I still faint at the sight of blood, when I get shots, or sudden pain, it sucks). In each of those experiences, what was once such a carefree situation was suddenly rife with pain and disappointment, and even if it hadn’t happened to me directly, I’d seen it happen right in front of my eyes.

NEGATIVE EXPECTATIONS

Over time, I became more and more afraid of getting hurt. More and more scared of heights, of climbing trees, of swinging high in the air (and of staplers, don’t judge me). When I was young and naive, I didn’t expect to get hurt, so my expectations were positive. I was overly optimistic. I expected to be able to do whatever I wanted and had no negative expectations of any given situation. As I got older and time passed, I witnessed and experienced negative consequences, and my fear began to grow. I began to have increasingly negative expectations of the same situations I’d previously been unafraid of.

Each time I experienced some sort of disappointment or a fear-inducing event, my expectations became dramatically negative at first. When my friend broke his arm falling from the topmost branch of our favorite tree to climb, I refused to climb that tree for months. I had the negative expectation that I, too, would fall and break my arm. Similarly, the first time I had my heart broken at 13 by my middle school boyfriend, I was terrified that it would happen again the next time I dated a boy in high school. I was scarred, and I didn’t want to put myself in a position that would allow that heartbreak to happen again. I was closed off and pessimistic.

My increased negative experiences and disappointment resulted in negative expectations that were debilitating in many situations. In time, however, those expectations changed again.

INCREASED EXPECTATIONS

They say “time heals all wounds” and I believe this is true to an extent - but it’s especially applicable here. Over time, the pain we might have once experienced in a situation begins to diminish. It’s like our expectations recharge, and build up again. We are once more hopeful, and we start to have more positive expectations (that have the potential to come crashing down). It’s as if we’ve forgotten the pain we endured before, and as good things happen our disappointment reduces, and we begin to increase our expectations again.

“The sad reality is that we humans are forgetful creatures” - Greg McKeown

When I worked in finance early in my career, I worked for a company called Fisher Investments, founded by a man I greatly respect named Ken Fisher (Financial Columnist, Best-Selling Author, Investment Guru). I really liked Fisher’s approach to finance and investing, because much of what he suggested applied to many other aspects of human behavior and life. One concept that always stuck out to me was from his book, The Little Book of Market Myths - since I can’t explain it better than he did, here’s an excerpt:

“It’s been proven that investors feel the pain of loss over twice as intensely as they enjoy the pleasure of gain. That’s from the Nobel Prize–winning behavioral finance concept of prospect theory. Another way to say that is it’s natural for danger (or perceived danger) to loom larger in our brains than the prospect of safety.

This evolved response no doubt treated our long-distant ancestors well. Folks who naturally fretted, constantly, the threat of attack by saber-toothed tigers were likely better off than their more lackadaisical peers. (The best way to win a fight with a saber-toothed tiger is not to get into one.) And those who had an outsized fear of the coming winter likely prepared better and faced lower freezing and/or starving risk. Hence, they more successfully passed on their more vigilant genes. But obsessing about future pleasantness or the absence of freezing risk didn’t really help perpetuate the species.

And our basic brain functioning just hasn’t changed that much in the evolutionary blink-of-an-eye since.”

I truly believe in this evolutionary theory - that we feel negative experiences and loss twice as intensely as positive ones. It makes sense - how else would humans have survived this long? However, as Greg McKeown aptly puts it, humans are forgetful. This means that despite how much pain we may experience, over time, we start to forget that pain and our disappointment evaporates, allowing us to build up hope.

When our expectations increase, we are more prone to disappointment. A 2011 Time Magazine article about “Optimism Bias” states that humans may be hardwired for hope, and points to neuroscience and social science suggestions that we are more optimistic than realistic (by the way, in my research, I definitely found more recent articles about human hopefulness, I just liked this Time article the best - I’m not usually one to reference old research unless it still stands true today).

Despite the pain we’ve experienced in our lives, more often than not, humans are hopeful creatures. As I see it, we need that hope to keep going. But hope is dangerous, it starts to breed positive expectations, and we begin to think that we’re immune to negative consequences again. We start to think that yes, we worked hard so we’ll get that job, we slept well so we won’t have a bad day, we’re married and committed to a person, so we won’t get a divorce - we expect good things to happen. We open ourselves up to disappointment, and since life is life, we’re ultimately disappointed again.

LOWERED EXPECTATIONS

Lyrical genius Selena Gomez (credit where credit is due) said it best when she said, "comfort is the enemy of progress". Lowering our expectations in a situation is uncomfortable. It’s not what we’re used to doing. We have to actively force ourselves to lower our expectations in our lives so that we can continue to live peacefully, while remaining ambitious - avoiding a constant roller coaster of emotions. Instead of being overly optimistic and expecting good things to happen in any given situation, we must practice a realistic mindset and lower those optimistic expectations of a situation to keep us from extreme disappointment when life doesn’t meet our expectations.

I want to clarify that having lowered expectations does NOT mean giving up. It doesn’t mean not trying hard. It isn’t even meant to be a pessimistic concept. It means not stressing when the outcome of a situation doesn’t meet the expectations you set - because you haven’t set unrealistically positive expectations for that situation. It means being satisfied with your hardest effort rather than your expectation of what the results should look like. The first few times life knocks you down, you’ll feel a little scarred. Lowering your expectations allows you to dust yourself off and try again.

THE CYCLE - INCREASED EXPECTATIONS <> LOWERED EXPECTATIONS

I think this is the most important part of anything I’ve written thus far (maybe ever). At 30 years old, I feel like life is a constant cycle of managing expectations. It’s a pattern of experiences, we either choose to learn from them or to ignore them and continue tripping ourselves up. For a long time, I’ve chosen to ignore negative things in my life because it seems easier. But that’s gotten me nowhere. I’ve built my expectations high up, thinking it will lead me to success to expect more of myself and my life, to “not settle”. But now, I don’t think lowering your expectations means settling in any way. It just means cultivating awareness, listening to yourself and others, and practicing being an observer in your life (on that note, I highly recommend essentialism: The Disciplined Pursuit of Less by Greg McKeown - it was a very enlightening read for me).

That being said, we are all human. And as I referenced above, humans are forgetful. As time passes, we can’t help but develop increased expectations. As a result, life is a constant cycle of setting our depending on where we are in our cycle of expectations, bouncing between increased expectations and lowered expectations. Often, this means lowering those increased expectations to achieve a healthy balance. This balance ensures that we’re not extremely disappointed, but also not unwilling to engage in life and face its challenges.

Having written all of the above, I have no idea what the key is to balancing our expectations at all times. I’ve said this before, but I believe that it’s a practice. It may come more easily to some than others (it’s very hard for me, I overthink absolutely everything). Being mindful of our state of expectations can help us to determine how much we should expect in a situation, actively manage those expectations, and avoid immense disappointment later on.

MOVING FORWARD

Even though I’ve purported that life is a cycle of increased expectations and lowered expectations, I think it’s important to note that if we don’t learn from each cycle, we’re doing ourselves a disservice. Each time I have to re-balance my expectations, I’ve learned something from the situation that incited that re-balancing. I try to keep my learnings at the forefront of my mind so that I don’t continue to get stuck in a cycle without getting closer to consistently managing my expectations. Most books and wise people would tell you to write down those learnings so that you don’t forget them - but I’ve never been disciplined enough to do that until now (it’s a work in progress).

It’s easy to feel proud of my ability to adjust my expectations after having increased them, but for my own sanity, I need to do that in a way that signals progress. As I move forward, I try to notice the patterns that caused that increased expectation, and as I lower my expectations and re-calibrate, I try not to let myself drop into negative expectations and get stuck. Since I’m now 30 (and can’t let go of that fact - I’m pretty sure I’ve mentioned it like 5 times in this post alone), I’m trying to make a change and document my learnings (aka blast them into the interwebs on this sad blog for your viewing pleasure), so that I’m less likely to wallow in my bad habits. I’m interested to see how my mentality progresses over time, and whether this cycle of expectations becomes apparent in my blog posts, too. I’m trying to practice what I’ve blabbered on about so far, so I’m not expecting much, just accepting life as it comes and trying not to care too much.

My ultimate goal is to have this cat’s attitude toward life:

youtube

So, whether you’re interested or not, I’ll be posting about how this goes for me. For now, I’m shutting up because I’m tired of writing about this. I hope this was a helpful read! Actually, as Chloe says, I don’t care about you or your problems LOL.

Notes

McKeown, Greg. Essentialism: The Disciplined Pursuit of Less. Page 77. Random House, 2014.

Sharot, Tali. “The Optimism Bias”, TIME Magazine. May 28, 2011. URL http://content.time.com/time/health/article/0,8599,2074067,00.html. Accessed on December 17, 2018.

Fisher, Ken and Hoffmans, Lara. The Little Book of Market Myths: How to Profit by Avoiding the Investment Mistakes Everybody Else Makes. Fisher Investments. John Wiley & Sons, Inc, 2013.

#loweredexpectations#lifeafterthirty#essentialism#theessentialist#thesecretlifeofpets#optimismbias#thelittlebookofmarketmyths#kenfisher#fisherinvestments#behavioralfinance#evoution#prospecttheory#humanbehavior#expectations

0 notes

Text

Why Saves Are More Real Than Any Other Closer Stat

From time to time I notice things in “the real world” that can be further explained with behavioral economics. Today’s topic is baseball’s save stat.

Ask any baseball stathead their thoughts on saves and the value of closers and you’re sure to get a scornful response.

Announcers and sportswriters continue to question why teams’ seemingly best relievers are only used for save situations. Teams lose games without ever putting in their best reliever, and then that same pitcher “saves” a game 4 days later that the team very likely would have won anyway.

Surely, most front offices today (sorry Phillies fans) are using better methods to evaluate relievers. And surely this new information can be used to optimize how arms in the bullpen are used.

Yet the save stat prominently lives on and bullpens are still managed around it. Why?

Humans Aren’t Computers

Humans don’t act in their own rational self-interest. They don’t make logical decisions, they make emotional ones that often come from an irrational place. There are countless cognitive biases always in effect, and the rationality of a decision is bounded by the information we have at the moment we make it.

What’s going on in the case of closers, the save stat, and the decisions around those 2 things is a result of Prospect Theory. Prospect Theory is very interesting in itself - I recommend you click that link and read about it. The two components relevant to the context of this article are:

Losses hurt more than gains feel good. The effect is about 2.25 times more powerful. For example, according to the irrational human brain, avoiding a $5 surcharge feels equal to getting a discount of $11.25.

Humans are risk-averse when there is a high probability of feeling a gain, and they are willing to overpay for certainty. For example, given a 95% chance to win $10,000 or 100% chance to obtain $9,499, they’ll take the $9,499 (and probably even less) even though the expected payout of the first scenario is $9,500.

The End of a Baseball Game is Prospect Theory at Work

When it’s the end of a game, and it doesn’t feel certain that a victory is at hand (a reasonable cutoff for that feeling being a lead of 4+ runs), managers, GMs, fans, and players alike are all willing to overpay for the certainty of not feeling a loss. So in comes the closer for the save. This is normal, risk-averse, human behavior and it’s not going to stop until teams are managed by computers or Phil Ivey.

How about close games? Why are closers saved for when a team is ahead? And why aren’t they used in the 7th inning with no outs and Mike Trout coming up with the bases loaded?

Here are the possible outcomes of a baseball game ranked on a “feeling scale” from most powerful to least powerful.

-4.5: Losing when you thought you were going to win

+3.25: Winning when you thought you were going to lose

-2.25: Losing

+1: Winning

0: Game suspended due to rain

Pitchers can’t create a win (from the mound, at least). They can only not lose. So the 2 losing scenarios govern a manager’s bullpen decision-making in those close games.

Technically, a pitcher can’t “not lose” in the 7th inning as there are still 2 more innings to play. In that moment, there are all kinds of unconscious calculations a manager’s brain makes in the background to help him quickly decide how to optimize the use of the bullpen to not lose.

Whatever those calculations are, the decision is usually the same: the closer’s butt stays glued to the bench and in comes a non-closer reliever. And the real reason why, no matter what the manager says, is that he’s optimizing to avoid the greatest loss possible: losing when you thought you were going to win.

It’s fair to reiterate that this isn’t something managers are consciously doing. They aren’t calculating odds of victory (or not losing) and choosing a reliever accordingly. This is all happening unconsciously based on thousands of years of evolution that has turned us into loss-avoiding scaredy cats.

Saves = Loss Avoidance

So why is losing when you thought you were going to win so painful? Any loss sucks. It feels crappy. But when you thought you were going to win? That feels much worse! Why? It’s because your point of reference changed. You already felt and accounted for the gain of the win. So now instead of feeling one loss, you’re feeling that loss PLUS the loss of the win you thought you had. Major bummer!

The save stat is simply a representation of loss avoidance. Closers aren’t paid to accumulate saves. They’re paid for what the save attempt represents: an opportunity to increase the certainty that a team’s stakeholders won’t feel the pain of losing what, in their mind, is already a win. In other words, they aren’t paid to get saves, they’re paid to not get blown saves. This differs from what non-closer relievers are paid to do and, as we’ve already learned, humans are willing to overpay to avoid the loss of a near-certain gain.

That’s why saves and blown saves matter. They’re the best metrics we have to describe the reality of the irrational human brain of baseball’s decision makers.

What do the numbers say?

I used Spotrac’s Free Agent Tracker to get a list of all the free agent reliever signings from 2012-2015 (2012 is as far back as it goes). I used FanGraphs to filter the list of relievers to those with a SD-MD% of over 60% in order to remove the relievers signed for middle-innings mopop work. Depth relievers aren’t signed to not lose. Last, I compared the average annual value of the remaining closer contracts to the non-closer contracts to get a ratio of how much closers are valued over regular relievers.

I averaged the 4 ratios and it comes out to 2.91. To be honest, I thought it’d be more like 2, as the value of relievers signed to not lose (2.25) is half of those signed to not lose when you thought you were going to win (4.5).

This variance might be due to small sample size, incomplete data, using the wrong data, or perhaps I just don’t know what I’m talking about.

What do you think? Do you agree? Have a better idea of how to do the data analysis? Is this all a bunch of fuff?

1 note

·

View note

Quote

We don't see very far in the future, we are very focused on one idea at a time, one problem at a time, and all these are incompatible with rationality as economic theory assumes it.

Read more at http://www.brainyquote.com/quotes/authors/d/daniel_kahneman.html#T5VjU6r6vRjVrwgB.99

0 notes

Text

Un grafico per la felicità

Contenuto elaborato da: Vittoria Perego

Nel 1979 Kahneman e Tversky hanno elaborato un modello in grado di spiegare come gli esseri umani prendono le decisioni. Si tratta di un processo molto più complesso di quanto possiamo immaginare, le persone non sono così razionali e capaci di considerare ogni singolo aspetto quando devono fare delle scelte.

Questa teoria è applicabile anche al contesto quotidiano e alla sfera personale proprio come vien illustrato nell’articolo di Luigia Barzaghi pubblicato nell'osservatorio sul COVID-19 di aBetterPlace. In questo periodo di emergenza sanitaria e di forte incertezza abbiamo vissuto momenti di smarrimento e di angoscia, ci siamo trovati nel “terzo quadrante” quello in cui il dolore e gli effetti negativi vengono avvertiti in modo più profondo rispetto ai momenti di felicità.

Inoltre man mano che il tempo passa questa sensazione negativa va scemando e il dolore diventa meno forte.

Non spaventatevi, è un effetto del tutto normale, è una lettura in chiave comportamentale di un periodo che molti di noi stanno ancora affrontando. Esserne più consapevoli ci aiuta sicuramente a viverlo meglio.

Fonte: https://abetterplace.it/la-curva-della-felicita

0 notes

Quote

The effort invested in 'getting it right' should be commensurate with the importance of the decision.

The effort invested in 'getting it right' should be commensurate with the importance of the decision.

http://www.brainyquote.com/quotes/authors/d/daniel_kahneman.html

0 notes

Link

The prospect theory, which explains people's attitudes towards risk, continues to be a valuable resource for investors to consider

The Financial Post takes a weekly look at tools that will help make your investment decisions. This week: How understanding prospect theory can reduce portfolio risk.

0 notes