#realistically lucy and victoria would gravitate to each other

Text

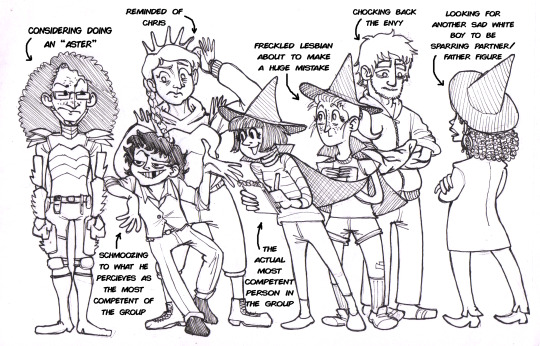

here they are, since we are going to hav some time before the next serial lets do a look back at how far we've come.

one thing i noticed out of all the fanart that grabs the protags and makes them pose as a team because shit just got real is that they never really interact with each other. each one is doing their own thing, so i wanted to explore how would they look like if they actually DID have to interact with each other. who would get along with who, who couldnt be able to stand the other. lots of fun.

#most of this is just a meme#realistically lucy and victoria would gravitate to each other#taylor would be off to the side doing threat assesment on everyone else#sy would be shooting the shit with verona who would try as hard as possible to keep up with the little shit#avery would try to have a nice conversation with blake i think she would sense that he needs it#worm#ward#pact#pale#twig#wildbow#fanart#fan art

411 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Life in Film: Elle-Máijá Tailfeathers & Kathleen Hepburn.

“We didn’t want it to be about the one-take, so we were actually kind of hesitant to speak about it before we released the film, because it wasn’t a gimmick.” The co-writers and directors of Canadian break-out feature The Body Remembers When the World Broke Open (now streaming on Netflix) talk single-take filmmaking, Indigenous representation, and identifying with Edward Scissorhands, as they answer our life-in-film questionnaire.

New Canadian feature film The Body Remembers When the World Broke Open, which landed well at Berlin and TIFF and was picked up by Ava DuVernay’s Array Releasing, follows two Indigenous women with very different stories who come into each other’s lives on one fateful afternoon in Vancouver.

When Áila (Elle-Máijá Tailfeathers) encounters the pregnant Rosie (Violet Nelson), bruised and barefoot on a damp footpath attempting to evade her abusive boyfriend, Áila whisks her away to her apartment and encourages her to seek help. But Rosie is paralyzed by a dearth of realistic options.

Tailfeathers, who also co-wrote and co-directed the film, is Blackfoot from the Kainai First Nation (Blood Reserve) as well as Sámi from northern Norway. Nelson is a member of the Kwakwaka’wakw First Nation (Kingcome Inlet, Quatsino).

With cinematographer Norm Li (who filmed Beyond the Black Rainbow) shooting in real time over a series of extra-long takes on Super 16mm, The Body Remembers… is designed to appear mostly as a single-take film. The supposedly hidden cuts are “impossible to spot”, writes Sean Baker. “This is absolutely not ‘just a gimmick’,” agrees Olivier Lemay. “The feature-length shot worked wonders at taking us on this real-time journey with the characters that became uncomfortably immersive.” The result is a grounded and intimate portrait of two unique members of a group vastly under-represented in cinema. “It feels based deeply in character and never exploitative,” writes Milly Gribben.

Sitting down with Tailfeathers (who goes by ‘Máijá’) and her co-writer and co-director Kathleen Hepburn, we wanted to know more about their filmmaking technique, and the films that have inspired them.

Elle-Máijá Tailfeathers (Áila) and Violet Nelson (Rosie) in ‘The Body Remembers…’.

What was the impetus for telling this story?

Elle-Máijá Tailfeathers: The film is inspired by an experience that I had in East Vancouver, where the film takes place. Like in the film, I encountered a young woman who had just fled her abusive partner and she was literally standing barefoot in the rain and was very pregnant. I spent a few hours with her and it was a transformative experience. Sometimes we are lucky enough to have these encounters with strangers that fundamentally alter us. I carried that experience with me for a number of years wondering what to do with it, wanting to honor her story, and just kind of was left with the question of what happened to her because I never saw her again. Ultimately, I decided I wanted to turn it into a feature film and honor her experience and our experience and what happened in that short time we’d spent together.

Most of my experience with directing has been through documentary, and then my experience with narrative film has been through acting. Knowing that I wanted to make a feature in real time, having never made a narrative feature before, I figured it would be a good opportunity to collaborate with someone with more experience. And the way that I learned as a filmmaker has always been through collaboration. Kathleen has been a friend for a number of years and I so deeply admire her work and just her as a person. Her feature debut Never Steady, Never Still, it’s a phenomenal film. I reached out to Kathleen and proposed the idea of co-writing and co-directing and doing this together and that’s how it happened.

Kathleen, how did you respond to Máijá’s proposal?

Kathleen Hepburn: It was a very immediate response. She told me what had happened in the real life experience. It just felt like such an important, rich story, very complex and also artistically quite challenging to tell a real-time story. We decided to do it in one continuous take. It felt like a really wonderful honor to be a part of this project and an amazing challenge that I was really excited to participate in.

Co-writer, co-director and actor Elle-Máijá Tailfeathers.

This film is putting characters on screen that haven’t seen a lot of representation. Was that part of the motivation?

E-MT: Yeah, absolutely. I mean, the two women you see in the film are so familiar to me as an Indigenous woman. I know these women, so in so many ways they’re by no means unconventional. They’re just very real people who exist who, like you said, haven’t been represented on screen very often.

In terms of Indigenous cinema and Indigenous representation, there’s this long history of misrepresentation and people who aren’t Indigenous telling our stories and getting it fundamentally wrong. This was an opportunity to explore a very simple story that embodies all of these larger themes in such a nuanced way. It was an opportunity to speak about issues of class and various forms of privilege that exist within the Indigenous community based on lived experience. It was also an opportunity to, yeah, explore these larger systems of oppression that impact Indigenous in very different ways on a daily basis in Canada. There’s so much richness to both of these characters and so many opportunities to explore these larger themes through their lived experience on screen.

Although this breaks a lot of new ground, were there cinematic precedents that you had in mind?

KH: One film we looked at in the writing process was Frozen River. In terms of style and tone, we were also looking at Andrea Arnold, Fish Tank. Wendy and Lucy, Kelly Reichardt’s film. But in terms of representation…

E-MT: I think Frozen River kind of set a precedent in terms of Misty Upham. She’s also Blackfoot. I’m a Blackfoot. She passed away very tragically, but seeing a woman like her on screen in a film that American audiences gravitated towards was pretty transcendent. Knowing that a character like that could hold space on screen in a way that drew American audiences in, I think kind of set maybe a bit of a precedent for this. Because we wanted Rosie’s character to be raw and real and vulnerable. When we found Violet Nelson, she embodied all of that and we wanted to present the world with a complicated individual who you would believe the world has not been kind to. Violet was all those things and she just delivered such an incredible performance and she was kind of like the light of our film. She carried so much of the film.

What precedents did you have in mind when you were thinking about shooting these long, real-time takes?

E-MT: There were a lot of things to consider. One thing I think that was obviously most important for the process was supporting Violet’s performance, and coming from an acting background I really appreciate the rehearsal process, especially with theater. You get to sit with the work and be with it for weeks before you go to the stage. There’s a really incredible momentum that builds and being able to do the performance from beginning to end in one go on stage.

And there’s kind of this palpable energy that builds also with the audience because it’s an experience you’re all having. We wanted to bring that energy and that process into the film. We rehearsed for four weeks, and also rehearsed with our crew for five days and carefully choreographed everything. Our cinematographer, Norm Li, and the rest of our crew, were all just fully on board for this wildly experimental challenge.

KH: I mean, obviously we were inspired by films like Victoria, but I think for us, we didn’t want it to be about the one-take, so we were actually kind of hesitant to speak about it before we released the film because it wasn’t a gimmick. It was more to give the audience the same emotional experience as the actors.

We’d like to ask you about your life in film. What movie made you want to become a filmmaker?

E-MT: I think for me it was Alanis Obomsawin’s Kanehsatake: 270 Years of Resistance. It’s kind of her most seminal work. She’s the grandmother of Indigenous cinema in Canada and also kind of around the world. She’s Abenaki, she’s 85 years old and she’s still making films. She just had a film at TIFF. She’s made over 50 films. Kanehsatake: 270 Years of Resistance is about the Oka crisis that happened in the early ’90s in Canada. It’s one of the most important works of cinema in Canada, and just knowing that an Indigenous woman made that film, that still is so incredibly important. I think that was the one that kind of motivated me to make movies.

KH: I think In the Mood for Love was probably the film where I was actually like, “Oh, okay, this is what filmmaking is like and can be like”.

Kathleen Hepburn, the co-writer and co-director of ‘The Body Remembers When the World Broke Open’.

What’s your go to comfort movie?

E-MT: I could watch Moonlight over and over and over and over again. I don’t know if it’s a comfort movie, but there’s just something so splendid and beautiful about that experience and I actually crave watching that film. I probably watch it once a month. I’ll just sit down and watch a section of it.

KH: This is a more recent film, but one that I just loved so much is Toni Erdmann. Just everything about it is so inspiring. It’s hilarious and heartbreaking. But I don’t watch it once a month.

What movie, or movie scene, makes you cry the hardest?

KH: Oh, I know this one. My Girl. When Macaulay Culkin dies, the funeral scene. “He needs his glasses. He needs his glasses.”

E-MT: God, that’s going to make me cry.

As a teenager, what movie, or movie character did you feel closest to?

E-MT: For sure, Now and Then. That was something I connected with, but that’s when it was twelve years old or something.

KH: I was a tomboy growing up, so there was an Elijah Wood film called The War. For some reason, that one always stuck with me. I don’t know. I wanted to be those little boys, I think.

E-MT: Edward Scissorhands. I so connected with Edward. It’s just such a wild, bizarre, beautiful story of this outsider, but no, I’m not a fan of Johnny Depp now.

What film do you have fond memories of watching with your parents?

E-MT: Oh man. Growing up we didn’t have a lot of money, but something that my parents always did was take us to the cinema and my dad, especially. On the weekends we would go and see double bills, sometimes not paying for the second movie. My dad was such an action movie guy. I grew up going to action movies with my dad. I remember, actually, my mom is the biggest Jackie Chan fan. Rumble in the Bronx, I think, holds a special place in my heart. It’s set in the Bronx, obviously, but it’s shot in Vancouver.

Then there was this Canadian TV show called North of 60, which was set in the north in Canada in this Indigenous community. It was kind of this show that we tuned into every week. I would say Tina Keeper, she’s an actress and also she’s a producer now, but she played a cop, an Indigenous woman. For me as a young person seeing her on screen was pretty transformative because she was an Indigenous woman who held a position of power and was a real person and was complex and beautiful and not framed within this overwhelming trauma that you often see Indigenous people framed within. That was pretty important just for me as in terms of representation, and then also for our family, we just tuned in every weekend. I don’t know if it’s even a good show. I can hear the theme song in my head. It was a CBC show.

Violet Nelson plays Rosie in ‘The Body Remembers…’.

What filmmaker, living or dead, do you envy or admire the most?

E-MT: Right now, Tasha Hubbard. She’s a Cree filmmaker from Saskatchewan and she made a documentary film called nîpawistamâsowin: We Will Stand Up. It was about the murder of Colten Boushie, a young Cree man who was murdered by a white farmer named Gerald Stanley. Gerald walked away from all charges and is a free man, and the film is winning all sorts of awards across Canada and it’s so brave.

Tasha grew up with a white family, she was adopted. She grew up in this white farming community and she’s an Indigenous person who has experienced both of those realities. Racism on the prairies in Canada is very prevalent and in-your-face and violent. As a person who comes from the prairies—and I have an intimate knowledge of that reality—just the courage that Tasha took to make that film and to fully invest herself in such a challenging process. Yeah, there’s no words to sort of describe the respect that I have for her and what she’s done.

If you were forced to remake any classic, which one would you choose?

E-MT: Well, this isn’t a classic, but one film that I’ve watched recently that just blew my mind is Happy as Lazzaro, the Italian film. It has such a high level of understanding about the world and the complexities of society, but it’s also just this beautiful film that tricks you into coming to an understanding that you don’t realize you’re having as you go through the film. I don’t have that sort of mind that can handle that kind of structural complexity.

‘The Body Remembers When the World Broke Open’ is the fourth acquisition of 2019 for Ava DuVernay’s Array Releasing, after acclaimed Ghanaian gem ‘The Burial of Kojo’, Hepi Mita’s documentary about his trailblazing Māori filmmaker mother, ‘Merata’, and Tribeca Film Festival award-winner ‘Burning Cane’ by nineteen-year-old Phillip Youmans. All are streaming on Netflix. ‘The Body Remembers When the World Broke Open’ is now in select theaters in New York, Los Angeles and Detroit.

#The body remembers when the world broke open#tiff#tiff19#ava duvernay#arraynow#array releasing#netflix#netflix film#elle-máijá tailfeathers#kathleen hepburn#canadian cinema#canadian film#indigenous directors#indigenous film#blackfoot#Kainai First Nation#Sámi#kingcome#Kwakwaka’wakw First Nation#letterboxd#interview

35 notes

·

View notes