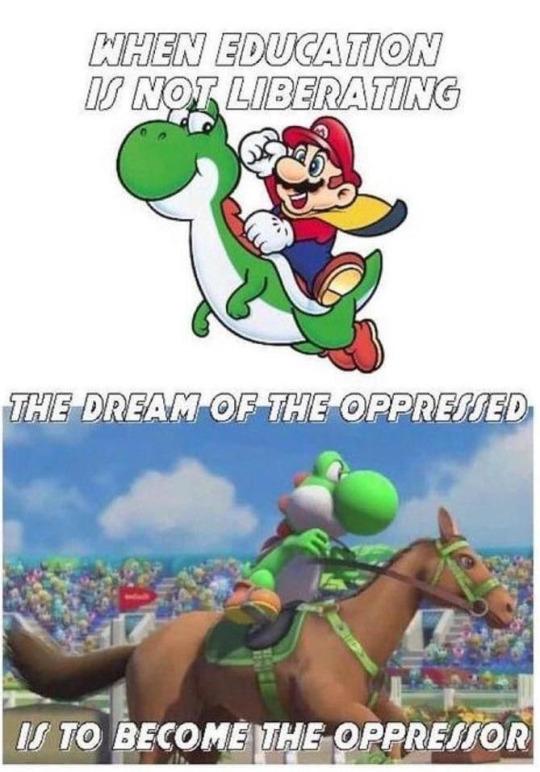

#while we all love the ideal of the model oppressed person who only seeks liberation... there will be people who instead lash out

Text

#for the people continually dumbfounded that oppressed people commit lateral oppression and leverage what privilege they do have to...#oppress others instead of seeking liberation or the dismantling of oppressive systems#furthermore... when one group with more power than you oppresses you... you have every right to resist that oppression#even if the group oppressing you is also being oppressed#while we all love the ideal of the model oppressed person who only seeks liberation... there will be people who instead lash out#and the more axes of oppression one is under will inherently make the person feel more entitled to 'punch upward' as there are more targets#so rather than tokenizing and scapegoating the oppressed person who is swinging at the other oppressed person...#(regardless of the second person's position in the 'progressive stack')#ask yourself who is benefiting from this infighting? who is instigating it? who is maintaining the systems of oppression that cause it?#who is showing it to you?#who is platforming it?#why is this inter or intra communal beef being displayed to outsiders?#because once you can answer these questions#you'll be a lot less fucking dumbfounded

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

The “I” in Christ

Commissioning, Community, and Lessons From Hamilton

(My second sermon, for Confirmation Sunday. You can also listen on Soundcloud.)

This Sunday, a few of us are about to confirm our formal membership in this community of St. Andrew’s; we do this with a profession of faith, along with a promise to seek justice and resist evil. Not only does the process of confirmation ask the question of what it means to be part of a Christian community, but this passage from Luke (10:1-11,16-20) also poses the question of what it means to live out our own discipleship beyond the walls of the church — especially in an age where the image of door-to-door missionaries is something of a bad joke.

Perhaps Christianity’s best-kept secret is this: the actual gospel of Jesus is tremendously relatable to anyone else whose mission is also to seek justice and resist evil. These first disciples were instructed to bear one message: that “the Kingdom of God has come near” — or, to put it in more contemporary language, we might say “another world is possible”.

Jesus says to carry no extra gear, going out like lambs into the midst of wolves; greeting no one on the road, but traveling in pairs. This is a radically vulnerable commission — relying entirely on the generosity of strangers, who may not even care if you live or die — but it is also a commission of interdependence and reliance on one another. Sometimes, we might retreat by ourselves into the metaphorical desert for a while to figure things out. But when we go forth and proclaim the good news of the Kingdom of Heaven, we’re not meant to go it alone. And so, from its earliest moments, Christianity is lived out in relationship.

We also see this in how the very early Christians came together in table fellowship — the root of our communion ritual. Jesus and the disciples had caught on to something that’s borne out by sociological science today (this is why we also had lunch as part of our confirmation classes): deep down, our brain associates “the people with whom you eat” with “family”. This becomes especially resonant when we consider that Jesus’ ministry seems to have been responding, at least in part, to the breakup and dispossession of families caused by Roman encroachment on Jewish ancestral farmlands.

So part of Jesus’ message to these seventy disciples is about going out and finding allies — and through that work, making new and cohesive communities in a time of tremendous social upheaval. Then and now, Christianity creates familial structures that counter the systems of injustice in the world with a message of radical community and genuine connection.

The New Testament, in the original Greek, calls this concept of community or fellowship koinonia, literally participation, partnership, or sharing, with emphasis on the element of relationship; a koinonos, used in the Epistles to describe the disciples’ relationship to Christ and to one another, is a sharer, partner, or companion; a joint participant. So, when we become part of the Body of Christ, we become partners, koinonoi, in acting out God’s intent, “on earth as it is in heaven”. As Jesus says when he is asked when the Kingdom will come (later on in the Gospel of Luke), “the Kingdom of God is among you” (Luke 17:21).

So I suggest that we can look at koinonia — this radical companionship — as a concept that has four pillars. They are economic, interpersonal, internal, and political — and together, they answer a world of imperial domination and hierarchical, transactional relationships with the egalitarian, reciprocal relationships of a truly divine community.

Most of us grew up hearing the Gospel story of how a few loaves and fishes fed five thousand people. When Jesus says “give them something to eat”, the disciples respond with “but how can we possibly go out and buy enough bread for everybody?”. But Jesus had a plan — and we are told that “all ate and were filled” (Luke 9:10-17). This isn’t just a fanciful miracle story; in Jesus’ world, everybody gets enough. This is a total reimagining of our economic model.

We see this principle carried out in the book of Acts, chapter 4: among the growing circle of disciples, it’s said that “there was not a needy person among them”, because people sold their possessions and shared the proceeds; “they laid it at the apostles’ feet, and it was distributed to each as any had need” (Acts 4:32-35).

“But that could never work!” we say, just like in the story of the loaves and fishes. I may not be an economic theorist, but my guess is that what gets in the way is our own self-interest; of course it won’t work if you assume that you and everyone else are just looking out for number one. The missing ingredient here is what the Bible calls lovingkindness, or what I call radical compassion — the key to the interpersonal aspect of the Kingdom of Heaven.

Remember, Jesus’ program is about treating people like family. And what happens when people feel safe enough, trusting enough, to be able to treat each other as a functioning family? “You’re in need? That’s okay, I’ll cover you.” — “Whatever happens, you’re still my sibling in Christ.”

This ideal of the family of God doesn’t end at the steps of the church, by the way. This is what Buddhist teachings mean when they talk about widening the circle of compassion: Talk to your neighbours. Look a panhandler in the eye. Fall in love with the immigrant kids down the corridor who won’t stop bouncing off the walls. Invite that raggedy backpacker down on Spring Garden Road to brunch. But, Jesus cautions, don’t make a big deal out of it; this is just what we do.

But again, we worry, just like the disciples: what if there’s someone in this community who’s really needy, taking up all the available resources and emotional energy? Perhaps that’s where a community can do its best work: helping a person become self-sufficient. Finding them a therapist, even if it means emailing every private practice in [the immediate area]. Finding them meaningful work in the community, something that provides for them and reminds them that their life matters. Granted, that’s extremely hard to do under late capitalism — but maybe that’s a specific challenge for Christians today!

We don’t claim to offer miracle cures here, but we do offer compassion and grace and walking with someone on the road to healing. And if you’ve bought into the Christian message, you’re already imagining the possibility of becoming whole — recognizing the image of God within yourself — and if you know any trauma survivors, you already know that that’s half the battle.

And to support each other like this, we have to be comfortable with being vulnerable. Paradoxically, that’s very hard to do in our white, English, North American church culture!

My childhood pastor used to say that a good church has to be so much more than just “a club for nice people” — part of that is because niceness and civility as we understand them involve building very specific walls around yourself, so that no one sees the mess and the struggle underneath your calm exterior. But when others see that you’re a flawed, messy human too, they respond in kind.

The very best of my church relationships are the very few people to whom I can confess almost anything, and they can confess almost anything to me. We inevitably find ourselves going deep; we have long conversations that are intense and sometimes unsettling, but I always come away feeling more fulfilled, more whole than I was before. And what is salvation in the original Greek but a kind of healing, or “making whole”?

That leads us into the internal work of the Kingdom of God. The hardest lesson we can hope to learn is to give up our preconceived notions of how things ought to be and what others are like. This is where contemplation comes in; it’s about letting go of our hangups so that we can see the bigger picture. This process of self-emptying seems like such a bewildering thought, but it’s a fundamentally liberating process. Just ask our Buddhist neighbours.

So, Christian community calls us to break free from our own self-interest by living as members of one body; as a collective of voices working together in constant dialogue. One might say that there is no “I” in Christ.

And here is where being political comes in. When we live together in lovingkindness, in partnership, when we let go of our attachments to see things as they really are — we begin to see that this is exactly the opposite of what the world wants, both then and now.

We’ve heard [St. Andrew’s lead minister] Russ [Daye] speak of “sin” not so much as an individual moral failing, but as the state of a society propelled by self-interest and operating through systemic inequality, oppression, and violence. And when we see the big picture, we start to see that that’s exactly what’s going on.

A fully realized Christian life, lived out according to the principles of radical community, makes the scales fall from our eyes and highlights the terrible workings of inhumane disconnection and self-interest that our society is based on. That, in the eyes of our world, makes us dangerous.

I recently had an extraordinary online conversation with another queer ministry hopeful, who is not afraid to state point-blank that “love cannot exist [or cannot exist fully] in a space where we are complicit in our neighbours’ suffering and exploitation”. We both agreed that a lot of us moderate Christians aren’t politically active because we can’t truly fathom how deep-rooted these systems of oppression actually are, let alone have any idea of how to stand up to them.

But I invite you to consider that the kind of strong support structure that a fully realized Christian community can provide can be a living “no” to the Caesars of this world, and can empower us to speak our truth to their face, no matter the consequences. “We know love by this,” says the epistle of 1 John, “that he [Jesus] laid down his life for us — and we ought to lay down our lives for one another” (1 John 3:16).

Perhaps, then, there are many “I”s in Christ — together, we are the pillars that hold up God’s kingdom.

However we choose to confront the Caesars of our world, we must always centre our love for God and one another in our actions. This can mean letting our hearts break at the injustice all around us — remember, we are called to be vulnerable! — but it also means means finding and creating opportunities to speak out and stand up for justice; equipping one another with the skills to do so; and lifting each other up in support when those opportunities come.

Let me tell you a story about one such situation.

On June 15, only a few weeks ago, the Pride festival in Hamilton, Ontario was confronted by a group of right-wing agitators carrying giant banners with homophobic messages, shouting slurs, and threatening physical violence. Shamefully, many of these people had the gall to call themselves Christian, using our faith as justification for their hatred and aggression.

Hamilton police, for their part, did very little to protect the Pride marchers.

(By the way, I’ve tried to rely on firsthand accounts of this situation wherever possible.)

What did happen at Hamilton Pride was this: after a similar encounter a few weeks earlier in Dunville, Ontario, where homophobes and counter-demonstrators spent six whole hours trying to drown each other out, an affinity group formed in Hamilton with a new plan. They built a thirty-foot-wide, nine-foot-tall barrier out of black cloth, practiced moving it around as a team — and when the right-wing agitators showed up, the affinity group moved their barrier into position and physically blocked the agitators off from the rest of the festival. They intentionally did not raise their fists to strike at anyone.

But — they still got beat up. As the original members of the affinity group dragged themselves away from the fists and helmets of these right-wing bullies, they looked around to see people they didn’t even know rushing to the scene and keeping the barrier standing. The barrier, incredibly, remained intact until the police arrived a full hour later, escorting the troublemakers out of the park with their hateful signs in tatters.

Community. We lay down our lives for one another.

When asked why the police didn’t get there sooner, an eyewitness reportedly heard the officer respond, “Don’t you remember we weren’t invited to Pride? We’re just going to stand here, not my problem”. [x]

There are, of course, many more layers to this story than I have time to get into here. But the ongoing aftermath of this situation is worth talking about.

The queer community in Hamilton was furious and disappointed, if unsurprised. Remember that there is a decades-long history of criminalization and persecution of queer communities by police, and of police turning a blind eye to homophobic and transphobic violence. That tension doesn’t go away overnight, and it is still very much with us today.

A few days later, a local queer activist named Cedar Hopperton was arrested, purportedly because being present at Hamilton Pride had violated their parole conditions related to a previous act of civil disobedience. (Like me, Cedar goes by the pronouns “they” and “them”.)

But here’s the thing: according to eyewitnesses, Cedar wasn’t part of that incident at Pride. They had stayed at home, where their friends came to them for support and first aid following the confrontation. When Cedar got access to the paperwork associated with their case, it focused almost exclusively on a public speech they had given at City Hall in the wake of the events.

And while they had been heavily critical of how Hamilton police have repeatedly let their community down, they framed their criticism with a prophetic statement:

“...what I am interested in is building community around people who [have] a desire to build a shared idea of the world they actually want to live in. I feel like that’s a higher bar [which] is worth working towards.” [x]

That is what those seventy disciples were sent out to find: The Kingdom of Heaven is near. Another world is possible.

In response to this and what would become at least four other arrests of queer community members, along with frantic attempts to save face by the police and by City Hall, the local activist community decided to go straight to the mayor. In a wonderful example of non-violent protest, some twenty people “dressed in gay masquerade attire” showed up on the mayor’s front lawn early on a Friday morning, and spent fifteen minutes making a ridiculous racket while planting hot pink lawn signs that read “The Mayor Doesn’t Care About Queer People”.

Within an hour, the same mayor who had largely refused to comment on the issue of right-wing agitators harassing and assaulting people at a Pride festival was in the news decrying the lawn sign action as a “violent attack”, and vowing that the perpetrators would be prosecuted to the full extent of the law.

That afternoon, one of the organizers of the lawn sign action found herself cornered by no less than eight police cars. After being brought in for questioning, she was escorted by officers with assault rifles to the central police station, where she was held overnight.

Only one of the right-wing agitators has since been arrested. The mayor, in a stunningly oblivious move, concluded the day by issuing a boilerplate supportive statement about the fiftieth anniversary of the Stonewall Riots.

The organizer who was arrested following the lawn sign action (who has chosen to remain anonymous) had some insightful words that I’d like to share with you. For me, they may as well have been spoken by an apostle in the first century. She said:

“[This is] about us as a community getting stronger — and them being afraid of that. We know [that] because within five hours they mobilized an investigation, manhunt and takedown. We know because they confront us with shaking hands and assault rifles. We know because they [subsequently] responded to a queer dance party with eighty officers on a Friday night. We see it when they make desperate arrests; [like] Cedar for a speech at city hall.” [x]

Because when we start to make a dent in the facade of unjust power, the mask slips, and the true cruelty and desperation of the people at the top gets revealed; just like the crucifixion of Jesus laid bare the horror that the Roman Empire was capable of. And yet, in ways that we do not yet fully understand, we are told that Jesus performed one last radical act of turning the tables; using that humiliating, commonplace death as a jumping-off point into the coldest, darkest reaches of the cosmos, where he sowed the love of God into the very ground of the universe.

Our anonymous lawn sign activist continues:

“In that, we can also acknowledge something else; we are winning. They are afraid of us and what we can do. They are embarrassed. They are losing ground.”

This takes us right back to Holy Week — when the authorities start planning Jesus’ arrest in the wake of the non-violent protest march that we remember as Palm Sunday, because they’re afraid he’ll incite the people to rebellion. When we start to successfully seek justice and resist evil, the powers that be, propelled by self-interest and sustained by systems of cruel inequality, are terrified.

She concludes with this wonderful statement of commission — and I’d like to think it can be our commission too:

“So let’s keep this up. Let’s keep getting into ... public spaces. … Challenging the things that harm us — even when they are institutional and systemic. … Let’s build towards the world we want to see – and share and learn those skills together. … Not just every four years — [I would add, not just every Sunday] — but every single day”.

Amen.

July 7, 2019 (Confirmation Sunday) — St. Andrew’s United Church, Halifax

Selected further reading:

Center for Action and Contemplation, “Consumed with Love”

Queer Theology podcast, “A Community of Care”

Rethinking Religion, “Buddhists Don’t Have to Be Nice: Avoiding Idiot Compassion”

#tamsin writes#tamsin sermonizes#queer christianity#queer theology#anti-oppressive christianity#Reclaiming Christianity#rethinking theology#united church of canada#uccan#faithfully lgbt#long post

2 notes

·

View notes