Text

This was tough...

Just as an aside, this blog was really tough to do because I love all the movies that I had to tear apart for this assignment. I think there are advantages in criticizing a film you really love though, and I hope I can now, after doing this project, view more films with a better critical eye, even if I love them to death. There is no perfect film that everyone will enjoy, which makes each film a unique piece of art, similar to the way an original painting is so awe-inspiring in its presence. Anyway, this may have been hard to do but I enjoyed every minute to watch (and it gave me a reason to re-watch so many of my favorite films).

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Shawshank Redemption and Prison Life in the Mid-1900s

Arguably one of the greatest films in history, The Shawshank Redemption is an incredible story of an unjust imprisonment, an almost impossible escape plan, and above all the story of the incredible power of hope. The story has a feel-good ending and very well may be one of the most well-known and most appreciated prison break stories of all time as the film finds itself incredibly high up on many best movies lists. However, as a film set in a 1960 Maine prison, some argue that the focus on hope and having a redeeming ending overshadows the need for a realistic representation of what prison life was like and how plausible the escape may have been. The film ils indisputably one of the best of all time, but the way that the inmate lifestyle is represented and the plausibility of the escape seem to be lacking in realistic nature.

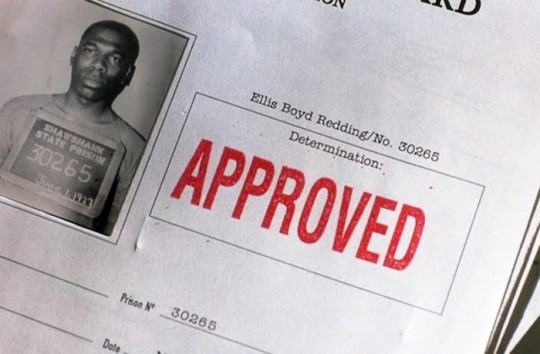

One criticism that Shawshank has had is the lack of depictions of truly terrible people that have been placed in prison as shown in the photo below. It is true that not all people in prison are awful people, but there is certainly a lack of representation of those who have no remorse for their crimes, aside from Boggs and the sisters. “Shawshank presents prison as sort of a really crappy summer camp: the activities suck, and there are a lot of terrible things that can happen to you, but if you make the right group of friends (i.e. not the violent rapists), you’ll be ok. In order to be a reasonably honest depiction of prison, I don’t think that all of Andy’s social group needs to be made up of unrelentingly awful people, but I do think at the very least they should either struggle with rehabilitation from their past crimes (accepting guilt or lying to themselves etc.) or they should be depicted in some way that demonstrates their criminality” (Morrison). In Shawshank, the audience is introduced to such pleasant characters like Red and Brooks, and most of Dufresne’s friend group is made of not-so-bad people, as they seem generally stable and kind to him. While I agree with Morrison as I do recognize that not all those sent to prison are truly evil people, there seemed to be an lack of diverse representation. The only truly sinister characters shown are Boggs and the sisters, with the rest of the antagonists being prison wardens or guards.

In addition to the representation of the people within the prison as a little too optimistic, the prison itself, within the time period in which the film is set, also seems a little too nice and lenient. One very popular phrase in the film is that all the prisoners in Shawshank aren’t guilty of the crimes that they supposedly committed. “Shawshank draws its strength from our attitudes towards prison and prisoners, but it then betrays the truth of its setting by setting up a falsely optimistic worldview where none of the characters are really guilty and their only task is to fight against an undeserved oppression” (Morrison). Again, Morrison makes a good point as Dufresne is depicted as the leader of a just cause, fighting for the supposedly “undeserved oppression” that the inmates are experiencing. However, as it will be explored later in this paper, the prison harshness might have been just the way things were handled in back then. In a true to life prison, not all the inmates might have been worthy to fight against institutionalization because of the seriousness of their crimes.

Along the topic of institutionalization, the circumstances in which Red finally receives his parole are almost comical to imagine as a real situation that would happen. Near the end of the movie, after Dufresne escaped, Red is called in for another parole hearing, and essentially wins for rebelling against the institution that seems to want to keep him suppressed. While this makes for an amazing cinematic moment and a thought provoking scene for audiences to ponder, the plausibility of the exchange is almost negligible. In a comical sense, when Red goes to see the parole board, they continually ask him if he has been rehabilitated….It is not until his final parole hearing when he vehemently mocks the parole board, asking them "what is rehabilitation anyways?" He further states its a "bullshit word" so people can have a job. Interestingly, his parole is granted” (Sabol). Indeed, there is something a little funny about how Red finally is granted parole. Again, while the scene and its dialogue is masterfully written and delivered by Morgan Freeman, trying to imagine a scenario where that speech actually grants Red parole is almost impossible. Such a speech by a regular inmate, especially in the mid 1900s when this film is set, would almost certainly result in a denied parole.

To stress the implausibility of Shawshank as a realistic representation of prison life, a study was conducted where actual inmates were interviewed on their reaction to the film. Josephine MetCalf conducted interviews with former prisoners in the UK on their reactions to multiple prison break films. As expected, she found many former inmates found the films to be inaccurate to how prison life really was like. “Yet the scene in which The Shawshank Redemption’s fictional prisoners get to drink beers on the rooftop was deemed “laughable” by our contributors; it seems that we tend to overlook the film’s unrealistic elements in favor of its feel-good factor. Similarly, prisoners of different race and class would arguably not have mixed so readily in real-life 1940s America” (MetCalf). While these were not American inmates commenting on the topic, it is still incredibly persuading to hear from actual inmates that many aspects of the film are ridiculous like the scene in the photo below. While some prisoners do foster positive relationships with prison guards, such great benefits that come from them as shown in Shawshank are slightly ridiculous. In addition, after an incident like the one in the film where Dufresne played classical music over the intercom may have resulted in a more serious punishment than portrayed in the film.

As shown through multiple film reviews and in opinions from legitimate former inmates, The Shawshank Redemption appears not to be an accurate representation of inmate life in the mid 1900s. While the film does hit upon many crucial aspects of prison life and maintains an amazing storyline and appeal to hope, the accuracy of prison life has appeared to come second to the story, writing, and cinematography. Without discounting the popularity and incredible quality of the film, the representation of prison life and inmate experiences in Shawshank are not completely accurate to realistic situations in a 1940 to 1960 era prison.

MetCalf, Josephine. “What Prisoners Think of Prison Movies.” The Conversation, Nov. 9, 2015.

Morrison, Josh. “The Shawshank Redemption is a Bad Movie.” Wordpress, n.d.

Sabol, James J.”The Shawshank Redemption: A Review.” Journal of Criminal Justice and Popular Culture, vol. 4 no. 1 (1996) 15-17.

0 notes

Text

Blade Runner (1982) and Social Class

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hpvClE82PRA

Social class in the original film Blade Runner (1982) is very clearly defined, especially in quite literal representations. In the film, the wealthy live literally above the poorer people, in tall buildings above the ordinary or poor people walking around the foot of their massive skyscrapers. While the film does an excellent job of clearly defining the different roles and classes people fall into, the film only barely shows the extent to which the lower classes are treated in terms of bullying or abuse.

Blade Runner (1982) is certainly a masterpiece, drawing viewers into the atmosphere that almost no other film can provide. While the film is fictional (and let’s be honest, long enough as it is in it’s shortest cut form), the film does not do a very good job of portraying the hardships of the lower class, since hierarchical society can be seen as a form of bullying if the upper class abuses their power. Even still, the film is visually very pleasing, as one reviewer notes “The Blade Runner is a dystopian future film which portrays social class through the conventional showing of higher class people living above the lower class people and how they live in luxury yet lower class people live in squalor. This was also portrayed through the colour scheme of both higher and lower class people as the higher class people would wear a variation of colours whereas lower class people would be seen wearing dark and very similar clothing to each other” (Holland). The lower class, in addition, is seen teaming with life and culture in the scene where Deckard is seen walking through a market of some kind. None of the people there seem especially dismal or oppressed appearing as lively as packed Boston Commons.

Even when we do encounter Pris, a runaway replicant who is imitating a pleasure robot, she is not being directly bullied or talked down to. Deckard instead speaks kindly to her, not exemplifying or representing the abuse that she and other pleasure bots may be subject to. “Another replicant, Pris, wanders alone around an alley, trying to hide under some trash. She ends up encountering the very man her confederates have been looking for—J. F. Sebastian, the genetic designer. Pris is hungry, and together, she and J. F. Sebastian go to Sebastian's apartment, where they meet the weird toys he's personally designed and treats as his ‘friends’” (Shmoop). While there is an indication that Pris has hit some tough times, there is almost none of it represented in the film, aside for the fact that she was trying to hide behind bags of trash, as seen in the clip above. Even the blade runners, who are not glorified cops but the ones who are dealt to deal with the unpleasant situations, are not seen as shunned or abused as the lower class. The clear representation of class, therefore, doesn’t directly correlate with a clear representation of the abuse that the lower classes must have gone through in this dystopia, yet Ridley Scott seems to avoid that element of the universe for the most part.

Finally, in one study of Blade Runner and what McNamara described as the post-individual worldspace, she touches on a few distinguished critics that recognize that the universe that Blade Runner is set in seems a little too devoid of the unpleasant parts of society and social class. “Although visually compelling, this representation of Los Angeles is often perceived as devoid of criticism...Pauline Kael dismisses Scott's vision as an agglomeration of scenes that ‘have six subtexts but no text, and no context, either’ (82)...rather, pyramids that suggest the "Mayan" skyscraper aesthetic of the thirties (echoed on the interior walls of Deckard's apartment) and a strip club that suggests some filmic Istanbul or the Yoshiwara district of Fritz Lang's Metropolis…” (McNamara, 423). Again, while the fictional nature of the film does protect it somewhat from criticism, the scene is set in futuristic Los Angeles, bringing with it an expectation that the reality of the city might be portrayed. In addition, you would expect that a film that draws you into the grimy, raw action packed universe that it creates might have some indication of the horrific things that go on, and yet there is scarcely any to be seen that relates to the class dynamics of the future. Without taking away from the incredibly craftsmanship of the film, the plot does not make much room for the addition of the class systems and the effects they might have on those in lower positions.

"Social Commentary and Industrial Context in The Blade Runner.” Wordpress, Nov. 20, 2015.

"Blade Runner Scene 5 Summary.” Shmoop, n.d.

Kevin R. McNamara. “’Blade Runner's’ Post-Individual Worldspace” Contemporary Literature, Vol. 38, No. 3 (Autumn, 1997), pp. 422-446.

0 notes

Text

The Breakfast Club and Sexuality

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RG3-n9ABoLA&index=10&list=PLF37Yj4A_mOc-t7xKHInVQ73eQgZoVC9B

As a college student who has a younger brother who is gay, the discussion of his sexuality comes up fairly regularly, usually initiated by himself. Some of the topics he brings up are related to bullying and abuse of people who have sexual preferences that are different from the majority of society. I have heard enough conversations so I could analyze films like Love, Simon and talk about how his orientation could be the source of bullying or abuse. However, I wanted to focus on something slightly different for this blog post. Instead of orientation, something similar but not quite the same is the societal stereotypes of sex in general and analyze how they are similar to today’s pressures and how sex for men and women are different. In The Breakfast Club, the film does not quite truly destroys these and many other stereotypes, which can lead to problems especially as the film ages further and societal norms are continually changing as we move further towards the second decade in the 21st century.

According to Laura M. Carpenter’s study in the Sociological Forum, many of those young people who have not had sexual experiences have looked to films and mass media as a way of information, which places even more emphasis on Hollywood to take these subjects very seriously and portray them properly. “ Longitudinal studies have linked youths' sexual conduct to their consumption of media with sexual content. Brown et al. (2006) found that 12-14 year-old white boys and girls exposed to media diets high in sexual content...were significantly more likely to have had sex by ages 14-16 than white teens with media diets lower in sexual content, even after controlling for other predictors of sexual activity” (Carpenter, 808). The Breakfast Club, therefore, can be seen as a threat to the youth of society, especially today as things seem to get more and more liberal. The opportunity of children and young adults to consume such media without a definitive stance on whether or not sexual exploration is good or bad can be dangerous considering the film’s fairly ambiguous ending and the different context in which it was first created.

While The Breakfast Club may have a feel-good ending and have the majority of stereotypes destroyed, the case of sexuality and sexual harassment is still somewhat prominent even as the film rolls its credits. In one analysis of a modern discussion of the film, Christopher Borrelli of the Chicago Tribute notes that “Estevez is in detention for sexually assaulting a fellow athlete; Nelson's locker is scrawled with homophobic hate language; Ringwald says a relationship is one man, one woman. Thirty years on, where to begin here?...Emilio's character engaged in what we regard as hazing. Since sexual harassment happened, he would be in a Title IX lawsuit for years...though nobody talked about stuff like sexual harassment in schools then. Today, a school can't avoid its responsibilities with a situation like that" (Christopher Borrelli). By today’s standards this is a terrible thing to do to a woman, resulting in lawsuits and prison time as Borrelli states. While The Breakfast Club may be a timeless classic, some elements of the film such as the parts where it jabs at sexuality and social pressures are not fit for modern standards. Just like Steve Carell recognized that The Office would not see the same success in 2018, The Breakfast Club might not as well since it infringes on some of today’s social norms.

One final striking example of what was mentioned above is a retrospective look from Molly Ringwald in The New Yorker at the actions of Bender in the film. As exemplified in the youtube clip at the top, she mentions the subtle themes of sexual harassment towards her from the character Bender throughout the film. “What’s more, as I can see now, Bender sexually harasses Claire throughout the film. When he’s not sexualizing her, he takes out his rage on her with vicious contempt, calling her “pathetic,” mocking her as “Queenie.” It’s rejection that inspires his vitriol. Claire acts dismissively toward him, and, in a pivotal scene near the end, she predicts that at school on Monday morning, even though the group has bonded, things will return, socially, to the status quo. “Just bury your head in the sand and wait for your fuckin’ prom!” Bender yells” (Ringwald). She touches heavily on the scene where Bender hides under the table and catches a glimpse of Claire’s underwear as one such example of this sexual harassment. However, these actions seem to be blown over in the film. Claire does snap at Bender at one point, but even with that Bender still maintains a relatively powerful position in the conversation, even calling Claire a bitch.

It pains me to write this paper for my topic since I absolutely love The Breakfast Club, but the point can be made that the film may not see the same success in 2018 due to its offensive ideals that it touches upon and does not fully conclude or resolve. I must admit, as much as I appreciate the film today, the first time I watched it I was not left with an overwhelmingly feeling; there was a lot that was still to be resolved in the next few sessions of detention between the five students.

Carpenter, Laura M. “Virginity Loss in Reel/Real Life: Using Popular Movies to Navigate Sexual Initiation.” Sociological Forum, vol. 24, no. 4, 2009, pp. 804–827.

Borelli, Christopher. “'The Breakfast Club' 30 years later: Don't you forget about them.” Chicago Tribune, n.d.

Ringwald, Molly. “What About ‘The Breakfast Club’?” The New Yorker, Apr. 6, 2018.

0 notes

Text

42 and Race

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9P5jHPzoWQo

The word bullying often implies and provokes thoughts of young children in elementary and middle school. However, even though there are different terms for it as we grow up (like hazing, racism, sexism, etc.) doesn’t mean that the concept necessarily changes. Using bullying in a broader sense, it is possible to see more demographics and age groups as affected by hateful speech and actions. However, in today’s media, such bullying or hateful speech like racism is often either downplayed or over-dramatized when blockbuster and hollywood films are produced and cast, as in the film 42 (2013). In this film about the baseball hall of fame player and the first African-American player in the MLB, many renowned critics and film reviewers have criticized the under dramatization of Robinson’s life and also the manner in which the casting was conducted.

In one review by Richard Roeper, he noted “Boseman is a fine actor, and he looks like a baseball player in the spring training and game-time sequences, but other than one bat-breaking meltdown that takes place out of sight of fans and teammates, we rarely get that visceral, punch-to-the-gut true feeling for the pressure Robinson surely must have felt when he took the field in 1947 as a pioneer.” This scene can be found in the link at the top of this post. Roeper highlights that the representation of how Robinson was treated may not have been particularly true to life. This may be because Hollywood or film producers are trying to protect their audience from such extreme amounts of harsh language and violence. While this film is known to be revolutionary in revealing in public media the hardships that Robinson endured, it was still downplayed as a whole for one purpose or another.

In yet another review by Yohuru Williams on Huffpost, he said that “It is equally important to acknowledge Jackie Robinson’s view of the problem of police community relations. Although considered primarily a sports hero, Robinson participated in the Civil Rights Movement. Columns he wrote for several newspapers, including the Amsterdam News, regularly weighed in on issues of race and criminal justice.” While this may seem like a positive comment, in the larger context of his review Williams is commenting on the lack of representation of what Robinson did for the larger African-American community outside of baseball. Robinson, while being primarily known for baseball, is often overlooked in such areas, and is represented as such in the film 42.

Finally, Rosa K. Lembcke in her journal article Being Seen and Unseen: Racial Representation and Whiteness Bias in Hollywood Cinema, during the process of major blockbuster films, financial gain outweighs the legitimate recognition of the importance of representation. “The need for financial gain outweighs their interest in being culturally and racially diverse, which means that business is sometimes hard to mix with artistic integrity and cultural sensitivity. It is unfortunate. But you wouldn’t make a film about Jackie Robinson, the first black baseball player, and cast a white guy, right? They cast a black guy. But that movie is about race. “Ghost in the Shell” isn’t about Asian American identity or Asian identity. I think that is also a difference.” In this, Lembcke sees that the only reason representation of a certain race is even considered in a film such as 42 is because of the need for an actor to accurately portray a historically significant figure.

Clearly, many critics have a fairly consistent position that they take on Robinson’s and the African-American community’s representation in the film 42. Much of Robinson’s life, they argue, is still downplayed because of societal and film producer pressures to create a socially acceptable film to show on the big screen for a public audience. This, I believe is yet another roadblock that the film industry must overcome if we are to truly reach a point where we can accurately and fully represent those of all race, gender, creed, class and any other identity.

Roeper, Richard. “42.” RogerBert.com Apr. 11, 2013.

Williams, Yohuru. “Beyond 42: Jackie Robinson and the Quest for Racial Justice.” Huffpost, Dec. 24, 2014.

Lembcke, Rosa K. “Being Seen and Unseen: Racial Representation and Whiteness Bias in Hollywood Cinema.” Roskilde University Center, 2017.

1 note

·

View note