Text

SUMMARY

The film opens as Rose is found drifting alone in a small rowboat. Two fishermen find it and pull her onto their own boat, barely alive and in a horrible state. Her voiceover indicates she had been rescued from some terrifying experience and the film’s events are flashbacks of it.

Rose is part of a group of tourists on a small commercial boat. The Captain and his mate, Keith, share a fondness for Rose. Also on board are Dobbs, who is the boat’s cook; Chuck, another tourist; and a bickering married couple named Norman and Beverly. After trouble with the engine, the navigation system goes haywire when they encounter a strange orange haze. The others sense that something is wrong. Norman in particular becomes abrasive. In the darkness of night, a hulking ship suddenly appears and sideswipes their boat. The Captain sends up a flare, which momentarily lights up the eerie sight of a huge, rotting vessel wrecked nearby.

The next morning, everyone wakes to find the Captain missing. Realizing the boat is slowly taking on water, everyone evacuates in the lifeboat and makes for a nearby island. They see the huge wreck in the light of day; it appears to have been there for decades, nothing more than a skeletal framework, and now seemingly immobile, stranded on the island’s reef. The group is startled to find the body of the Captain, apparently drowned while he was trying to check the underside of the boat for damage. They explore the island and discover a large, rundown hotel. At first they think it is deserted, but they discover a reclusive old man living there.

The man seems alarmed by their story, and he goes down to the beach to personally investigate. Under the water, strange zombie-like men gather, walking from the wreck along the ocean floor to the island. As Dobbs gathers items to help prepare food, the zombies corner him in the water and one of them attacks; before it kills him, Dobbs falls in a cluster of sea urchins and is horribly mangled. Rose discovers his body while swimming. Back inside the hotel, their reluctant host tells them that he was a Nazi commander in charge of the “Death Corps”, a group of aquatic zombies. The creatures were intended to be a powerful weapon for the Nazis, but they proved too difficult to control. When Germany lost the war, he sunk their ship. Knowing the zombies have returned, he says they are doomed. The Commander goes down to the beach again and sees a few of the zombies off in the distance; they refuse to obey and drown him.

The others locate a boat that the Commander told them about and pilot it out through the streams to the open water. They lose control of the boat, and it sails away from them, empty. A zombie drowns Norman in a stream, and another chases Rose back to the hotel, where she kills it by pulling off its goggles. Chuck, Beverly, and Keith return to the hotel, and they barricade themselves in the refrigerator unit. The close quarters and stress cause the survivors to begin infighting, and Chuck accidentally fires a flare gun, blinding Beverly. Keith and Rose escape to an old furnace room, where they hide inside two metal grates, while Beverly hides in a closet. The zombies drown Chuck in a swimming pool outside.

The next morning, Keith and Rose discover Beverly dead, drowned in a large fish tank. Now on their own, they try to escape in a small sightseeing rowboat with a glass bottom. The zombies attack, and although Keith manages to defeat one by pulling off its goggles, a second one grabs him and drowns him just as the dinghy breaches the reef and drifts free. Rose sees Keith’s lifeless body pressed up against the glass bottom of the boat and screams.

The film comes full circle, and Rose’s voice over returns. She is now in a hospital bed, seemingly writing in a journal. Her dialogue begins to repeat itself over and over, and she is revealed to be writing nonsense in her journal, showing that she has gone insane.

Peter Cushing & Fred Olen Ray

BEHIND THE SCENES

Wiederhorn didn’t have much budget to work with on Shock Waves, but still managed to find intriguing, inexpensive ways to complete his first feature film, shooting everything in 35 days in 1975 although it wasn’t theatrically released until 1977. He was limited in how he could use Cushing and Carradine, whose contracts only accounted for four shooting days (both actors earned just $5000 each). He was able to secure a permit to film on the SS Sapona — a concrete-hulled cargo steamer which ran aground during a hurricane near Bimini in 1926 — and the Biltmore Hotel in Coral Gables, Florida, was rented for $250 per day, which was abandoned at the time.

Wiederhorn employed two cinematographers — Reuben Trane above the water, and Irving Pare below — who shot on 16mm (which was then blown up to 35mm for theatrical prints, accounting for the film’s grainy look).

KEN WIEDERHORN INTERVIEW

I want to ask you first, does the idea of talking about SHOCK WAVES and revisiting this title excite you still? How do you feel today about the film’s legacy and your role in horror history?

KEN WIEDERHORN: I love the film because it’s the movie that keeps on giving

Do you mean that in a financial sense or otherwise?

WIEDERHORN: In the financial sense. When you make your first film, little do you know that it’s going to follow you around for the rest of your life and keep putting money in your pocket so that’s always a very nice feeling. I’m delighted when anything happens with SHOCK WAVES

Were you born and raised in Florida?

WIEDERHORN: No I’m from New York.

Ok, so how does a New Yorker end up in Florida with Peter Cushing and John Carradine?

WIEDERHORN: I was working as an assistant film editor for a documentarian who had also made some feature films and somehow he wound up being appointed the head of the film program at Columbia and he said well if you’re interested in taking some more courses let’s talk about it. I’m pretty sure I can get you into the film program’. He in fact did that. So I have an MFA with no undergraduate degree. Anyway, there I met Reuben Trane who is from Florida who was also in the films program and we partnered on our thesis film which was called MANHATTAN MELODY and that won the first Motion Picture Academy Student Film Award. Then Reuben decided that he wanted try his hand at producing a low budget film and raised some money. The investors said basically we’re fine with this as long as you guys make a horror movie because we heard that horror movies always make their money back so that’s how that happened. He raised a couple hundred thousand dollars and I drove down to Florida and we figured out how to do it there

Why a zombie movie? Or did you even think of the Nazi ghouls as zombies when you were coming up with this idea?

WIEDERHORN: I was not necessarily a horror aficionado. I really worked in the cutting room and was coming up that way. I was still very much thinking that I was going to become a producer at CBS news so I can’t say that I came to it with a great deal of interest or expertise in the horror genre. I simply went looking for material. I found a book called The Morning of the Magicians which purports to tell about the Nazi belief in the supernatural and in reading that book somehow I thought, ok this makes sense. We knew we were going to shoot the film in Florida. Reuben knew his way around boats, we were going to be in Miami so the water element came in and I suddenly had a vision of Nazis attacking Miami Beach which could be quite humorous. See, the thing for me about horror is that it always walks the line with comedy so you have to be very careful to make sure you’re on one side of that or the other so I thought, no, we can’t go in that direction. That led me to thinking about soldiers underwater and one thing led to another and with the help of a few joints we came up with the idea of underwater Nazi zombies!

Even if you haven’t seen SHOCK WAVES, you know the art and you know those creatures which have been riffed on several times in several films but there’s a look to them. Alan Ormsby did the makeup FX and the Nazis remind me of his work on Bob Clark’s DEATHDREAM, Did you give Ormsby much guidance when it came to creating these creatures?

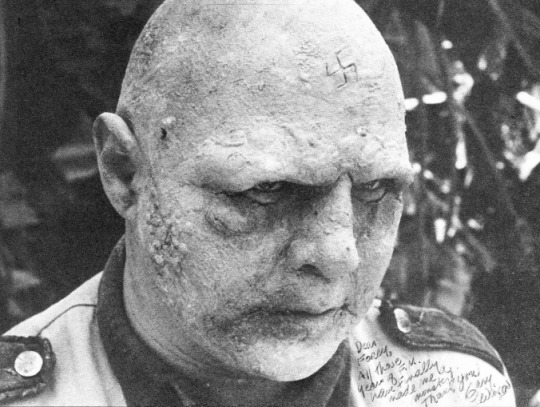

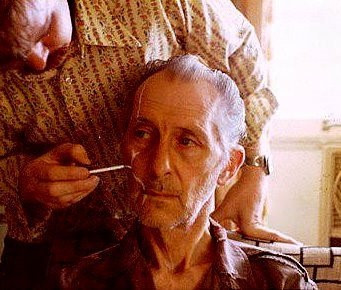

WIEDERHORN: I hadn’t seen DEATHDREAM and I still haven’t seen it so I had nothing to relate to in Ormsby’s background. I know he had worked on a movie called CHILDREN SHOULDN’T PLAY WITH DEAD THINGS. Listen, when you’re in Miami, you don’t have a lot of choices in terms of crew and people to help you imagine the film so I was delighted to meet Alan because I felt we were very like-minded. He thought the film would be very problematic because one requirement was that the makeup had to withstand exposure to water. We didn’t want to get bogged down with it washing off and having to re-apply it eight times a day so he very brilliantly came up with a solution for that and it was amazing how that makeup withstood the constant submersions those guys had to make. Now as far as the details of the makeup, I know that we already decided that we wanted to make their vulnerability be exposure to light so hence the goggles and we wanted to make sure they were blonde and that came about primarily because we got a deal with a Cuban beauty school in Miami to take the guys and strip the colour out of the hair with bleach and that was affordable and doable and that’s what defined that. But Alan certainly, I would say was ninety percent responsible for the look of the zombies.

Obviously people that love SHOCK WAVES always cite the heavy dense atmosphere that the movie trades in. Talk about that eerie ruined boat. Did you find the boat first and make the movie around it?

WIEDERHORN: The wreck is off one of the Bahamian islands so we could get there easily enough from Miami. Somebody had a chart of wrecks in the south Florida area that was more oriented towards treasure hunting and somehow this wreck was marked on the map and we investigated it and discovered it was an old World War II cement ship. The hull of the ship was actually made from cement. We saw pictures of it and we thought ok that will do and that was that.

Did the script reflect that they would run into some sort of ruin or did the ruin end up being written into the script because of the existing wreck?

WIEDERHORN: No, the script was always scripted that way.

Is the boat still there do you know?

WIEDERHORN: As far as I know.

Amazing. The other key element of the film is Richard Einhorn’s minimalist music. Was Richard your choice or was be brought to you?

WIEDERHORN: Richard was also at Columbia and he was studying with a professor whose specialty was electronic music. So I went to the department head and said I’m looking for somebody who can do electronics for a horror movie score and Richard was one of the people who they recommended and we sat down and talked. I thought he would do a terrific job and I think he did. I think that the movie owes much to its music.

It sure does and you used Richard again for “EYES OF A STRANGER as well didn’t you?

WIEDERHORN: Yep and then used him again for the last film I made called A HOUSE IN THE HILLS

He went on to quite an illustrious career as a composer…

WIEDERHORN: He’s more of a serious classical modern composer and he’s done all orchestral score for JOAN OF ARC and he’s very active in New York. Richard was always my first choice for anything I was doing.

Now we’ve got to talk about Peter Cushing. This is, I think, one of his last notable horror roles…

WIEDERHORN: Ah yes, Peter. The horror movies that I actually knew were Hammer films. Why that is, I don’t know but I knew quite a number of the Hammer films and what appealed to me about them was that they really relied on story to some degree. But even more importantly, atmosphere and quality of acting. They were well produced and they were able to work on that level. So I very much had that in mind. We knew going on that we did not want to get into a lot of bloody special FX because we were making a low budget movie and it seemed to me that the way to succeed was not to become overly ambitious. To really make sure that what we were doing was something that we could in fact do. So the element that cost the least is all the elements of building suspense. I look at the film today and parts of it seem terribly slow to me but I understand and I see how at the time it worked in its way. It certainly worked because what I hear from people telling me about their experience of seeing the movie when they were 13 years old on late night TV is that when you’re channel surfing, this film stands out because it looks different. I personally really hated the locations because they were really difficult to work in terms of physical comfort. It was hot, it was humid and we would have to cover ourselves with mosquito repellent several times a day. There were sharks swimming in the water that we were working in Biscayne Bay so I think that worked for the film. I wasn’t the only one having a difficult time with the physical element that we were working it.

But back to Cushing, his nickname while making the Hammer films was “Props” Cushing because he would always find a way to work the surrounding props into his performance. Did you see any evidence of that in his work? Was he resourceful that way?

WIEDERHORN: The only prop I think he had was a cigarette holder that he used. He gave me a preview of the accent and I thought well it’s not really a German accent but it’s an accent so it’s fine. The great thing about Cushing was that he was very giving and very professional and even though he probably saw a lot of us walking into walls during the day, he was helpful and extended himself in ways that I certainly didn’t expect. In fact one day I was trying to figure out how to set up a shot on a beach somewhere and he was always available and he was always nearby, it’s not like between takes he went off and sat in his trailer, he was very available. So he’s watching me having a problem figuring things out and he gets my attention and motions me over and he says “Dear boy may I make a suggestion?” and I said “Sure Peter, what?” he says “I think if you move the camera a little bit off to the right and you lower the frame a bit you’ll get what you’re looking for and damn, he was right! I realized this is a guy who’s had more set experience than most of the directors he’s probably worked with and I knew that he was observant to what was going on. He was watching and so whenever we were ready, he was always ready. Whereas Carradine who came from a different discipline entirely and probably had been in four times as many movies as Cushing was in, he didn’t want to know about anything except what’s my line, where do I stand and when can I get the hell out of here.

Peter’s wife passed in 1970 and apparently those who worked with him around this period said he almost had a death wish. He always talked about her in a very morbid way. Was he a melancholy guy did you notice? Was that evident at all?

WIEDERHORN: I would say no. I do know about the wife but all I can tell you is that he was very open and frank about the fact that he would communicate with her through various mediums.

Have you seen any evidence of SHOCK WAVE’s influence in any other films or pop art?

WIEDERHORN: Well, people have pointed out to me that there is a whole collection of Nazi zombie movies now and I really have no idea if SHOCK WAVES had anything to do with that or not, that’s for other people to figure out. Other than that. I know it happens that there are references made to it. Somebody sent me a mystery show where SHOCK WAVES was a central part of the plot…

What about a remake? Since everything even borderline cult has been remade or is in the process of being remade, there must be somebody knocking on your door to try and do a remake of SHOCK WAVES…

WIEDERHORN: Yeah, I get that knock on the door a couple of times a year but frankly it’s usually ‘let us take an option and give us two years and we’ll see if we can get something done and I’ve been around that track many times and I figure if somebody is really serious about remaking it or doing a sequel in some way it will either happen or not. I don’t really have any interest in doing it myself.

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

Promotional and Advertising Material/Lobby Cards

SOUNDTRACK/SCORE

Richard Einhorn’s haunting experimental, analog-synth score — one of the earliest electronic compositions created for film — is often singled out for its creative use.

SHOCK WAVES LP (Waxwork Records) Original Richard Einhorn Score

youtube

CREDITS

Cast

Peter Cushing as SS Commander

Brooke Adams as Rose

John Carradine as Captain Ben Morris

Fred Buch as Chuck

Jack Davidson as Norman

Luke Halpin as Keith

J. Sidney as Beverly

Don Stout as Dobbs

Directed by Ken Wiederhorn

Produced by Reuben Trane

Written by

Ken Wiederhorn John Kent Harrison

REFERENCES and SOURCES

Delirium Issue 005

Shock Waves (1977) Retrospective SUMMARY The film opens as Rose is found drifting alone in a small rowboat. Two fishermen find it and pull her onto their own boat, barely alive and in a horrible state.

0 notes

Text

SUMMARY

Alex Gardner (Dennis Quaid) is a psychic who has been using his talents solely for personal gain, which mainly consists of gambling and womanizing. When he was 19 years old, Alex had been the prime subject of a scientific research project documenting his psychic ability, but in the midst of the study, he disappeared. After running afoul of a local gangster/extortionist named Snead (Redmond Gleeson), Alex evades two of Snead’s thugs by allowing himself to be taken by two men: Finch (Peter Jason) and Babcock (Chris Mulkey), who identify themselves as being from an academic institution.

At the institution, Alex is reunited with his former mentor Dr. Paul Novotny (Max von Sydow) who is now involved in government-funded psychic research. Novotny, aided by fellow scientist Dr. Jane DeVries (Kate Capshaw), has developed a technique that allows psychics to voluntarily link with the minds of others by projecting themselves into the subconscious during REM sleep. Novotny equates the original idea for the dreamscape project to the practice of the Senoi natives of Malaysia, who believe the dream world is just as real as reality.

The project was intended for clinical use to diagnose and treat sleep disorders, particularly nightmares, but it has been hijacked by Bob Blair (Christopher Plummer), a powerful government agent. Novotny convinces Alex to join the program in order to investigate Blair’s intentions. Alex gains experience with the technique by helping a man who is worried about his wife’s infidelity and by treating a young boy named Buddy (Cory Yothers), who is plagued with nightmares so terrible that a previous psychic lost his sanity trying to help him. Buddy’s nightmare involves a large sinister “snake-man.”

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

A subplot involving Alex and Jane’s growing infatuation culminates with him sneaking into Jane’s dream to have sex with her. He does this without technological aid—something no one else has been able to achieve. With the help of novelist Charlie Prince (George Wendt), who has been covertly investigating the project for a new book, Alex learns that Blair intends to use the dream-linking technique for assassination.

Blair murders Prince and Novotny to silence them. The president of the United States (Eddie Albert) is admitted as a patient due to recurring nightmares. Blair assigns Tommy Ray Glatman (David Patrick Kelly), a psychopath who murdered his own father, to enter the president’s nightmare and assassinate him—people who die in their dreams also die in the real world. Blair considers the president’s nightmares about nuclear holocaust as a sign of political weakness, which he deems a liability in the upcoming negotiations for nuclear disarmament.

Alex projects himself into the president’s dream—a nightmare of a post nuclear war wasteland—to try and protect him. After a fight in which Tommy rips out a police officer’s heart, attempts to incite a mutant-mob against the president, and battles Alex in the form of the snake-man from Buddy’s dream. Alex assumes the appearance of Tommy’s murdered father (Eric Gold) in order to distract him, allowing the president to impale him with a spear. The president is grateful to Alex but reluctant to confront Blair, who wields considerable political power. To protect himself and Jane, Alex enters Blair’s dream and kills him before Blair can retaliate.

The film ends with Jane and Alex boarding a train to Louisville, Kentucky, intent on making their previous dream encounter a reality. They are surprised to meet the ticket collector from Jane’s dream.

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

The Dream Master Roger Zelazny

According to Roger Zelazny, the film developed from an initial outline that he wrote in 1981, based in part upon his novella “He Who Shapes” and novel The Dream Master. He was not involved in the project after 20th Century Fox bought his outline. Because he did not write the film treatment or the script, his name does not appear in the credits; assertions that he removed his name from the credits are unfounded.

DEVELOPMENT

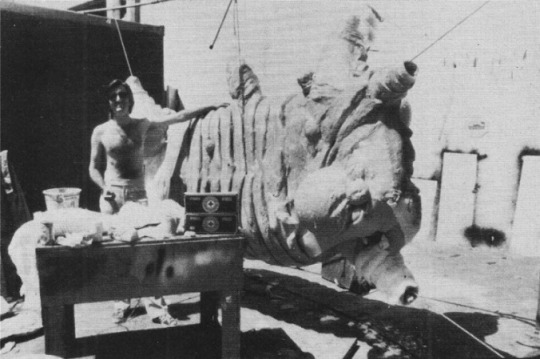

DREAMSCAPE’s title encapsulates both the film and the mental landscape that its independent filmmakers occupied for almost three years. Its creators hoped that the production would not only prove to be a success, but that it would also give them the clout to go on to bigger, even more ambitious projects. Featuring elaborate special effects by Peter Kuran’s Visual Concept Engineering Company and makeup effects by Craig Reardon, the film was launched as the first outing of newly-formed Zupnik-Curtis Productions.

Producer Bruce Cohn Curtis is one of the few men left in Hollywood who still has ties to its fabled beginnings, the nephew of the legendary Harry Cohn, one of the founders of Columbia Pictures. Looking the producer, from his immaculately clipped hair down to his tailored, sharply creased suits, a chill falls over any set that Curtis walks onto. With a military air of no-nonsense, Curtis keeps a close eye on his productions and is happy only if filming is on schedule.

“I’m tyrannical on a set,” Curtis says with a smile of relaxed authority. “That’s why I use the people I have as well as I do. Many of the people on DREAMSCAPE have worked with me before and have come back because I am a perfectionist and won’t settle for less. I have a standard of excellence in my films that I’ve always maintained, no matter what the cost, so that even though you might not like the stories I’ve done, the look of the film is always rich.”

Remembering that he had to prove himself publicly in an industry filled with people just waiting for the newest Cohn to fail, for his first effort Curtis made OTLEY, a sharp-edged spy spoof/drama with Tom Courtney as an ersatz spy who finds his make-believe assignment being taken very seriously by the other side. The film died at the box office, but drew good critical notices. The industry sat up and noticed; Harry Cohn’s nephew was off and running.

Curtis partnered with various producers for awhile, including Irwin Yablans on HELL NIGHT, but chafed at being the junior partner without clout. The matter came to a head when he was making THE SEDUCTION with Yablans and grew tired of having his ideas ignored.

Curtis resolved to start his own company and make pictures his way. He found financial backing from businessman Stanley Zupnik, and was looking for scripts to start Zupnik-Curtis Productions when associate producer Chuck Russell brought in director Joe Ruben and the DREAMSCAPE script. Curtis had worked previously with both and gave the green light for Ruben and Russell to begin revising the script, written by David Loughery.

Ruben discovered Lowery’s script in 1981 at the William Morris Agency, which represents both artists. Lowery, a television writer, had come out to Hollywood in 1979 after winning a script writing contest sponsored by Columbia Pictures, while a student at the University of Iowa. Ruben had just finished directing the TV-pilot for BREAKING AWAY, and was looking for a new project.

Once Ruben started reading the DREAMSCAPE script he found he couldn’t put it down. The vision Loughery described was breathtaking, with rivers ablaze and boats filled with the undead. Ruben was excited by the property and showed it to Russell, his assistant director on JOY RIDE and GORP (also starring Dennis Quaid), films made with Bruce Cohn Curtis for producer Samuel Z. Arkoff. Russell suggested they take the script to Curtis and his new company.

It took seven months for Ruben and Russell to rewrite DREAMSCAPE; with Curtis providing detailed criticism and ideas throughout. Loughery was brought back in to help write the final draft.

“We knew some things in Loughery’s script, like the holocaust dream at the end, were so expansive that it was virtually un-filmable,” said Russell about the changes that were made. “The original ending was set in New York. We changed that so we could do the movie out here in Los Angeles. In Loughery’s script you saw all of New York on fire after the bomb had hit. You saw the Statue of Liberty, ferry boats filled with the undead, and flames across the harbor. It was really great, but I knew we couldn’t afford to do it like that.”

Putting a screenplay into production inevitably means rewrites and not always by the original writer. In the final billing, Loughery receives story credit, while sharing screenwriting credit with director Joe Ruben and associate producer Chuck Russell. When I started writing with Joe and Chuck,” he says, “the original screenplay was pretty ferme, about 108 pages. They wanted to work some more on the characters, and their relationships. That was a good thing the development of the characters gave the audience more reason to care for the people and what happened to them.”

One of the things that really worried us about the character of Alex Gardner is that he’s something of a smart ass. So, we were afraid the audience wouldn’t like him. As soon as Dennis went to work, it was obvious we weren’t going to have any problem.

“My favorite character is Tommy Ray, the psychotic psychic, played by David Patrick Kelly. He doesn’t have many scenes, but when he’s on, he does a great job. The ‘have a heart scene is going to be seen by the audience as a rip off of Temple of Doom, but the fact is we shot it months before Temple of Doom even went into production. That is Chuck’s idea; he has a grisly and macabre sense of humor.”

Russell and Ruben beefed-up the character of Buddy (Cory “Bumper” Yothers), the little boy whose nightmares are cured by the film’s dream research project. In Loughery’s script Buddy wasn’t a running character. The idea for Buddy’s character arose from concepts the writers picked up from the study of dream research.

“We found the case of a little boy who was having such terrible nightmares that he couldn’t sleep,” said Russell. “It was affecting him physically; we used that case as our model for Buddy. The first time in the film when Alex (Dennis Quaid) acts unselfishly is when he enters Buddy’s dream to try and help him. He rises to the occasion and fulfills the role of hero.”

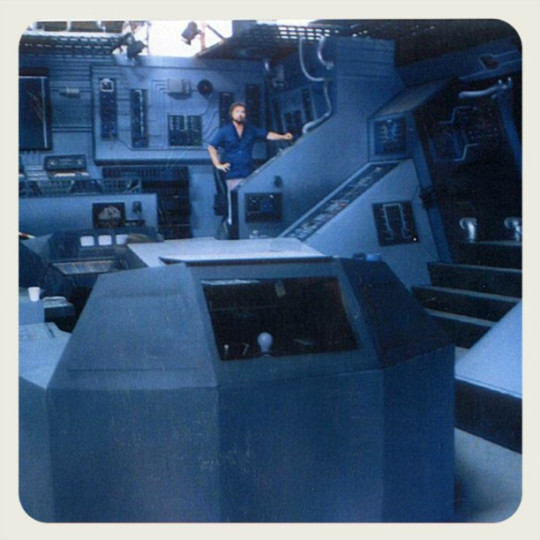

THE DREAM CHAMBER

On an adjacent stage the set for the Dream Chamber was built. Outside, the set looked like a plywood igloo circled with florescent lights. Inside however, a small, padded chamber led to a main control room by a door and a large window. The set was a quiet haven, even when the normal racket of production was going on outside.

“The initial sketches of the set design for the Dream Chamber were some wild approaches that we felt were interesting, but not what we wanted,” Russell said. “Some of them made us feel too much like we were on a spaceship, while others were more like a classic, BRAINSTORM-type, wire-strewn lab. We decided we didn’t want a lot of whirling lights and buzzers, but something quiet and womb-like. It was a very difficult set to design because we were trying to make something that looked authentic, but we didn’t have any precedent for it.”

From an aesthetic standpoint, the design worked wonderfully. From a practical standpoint however, problems cropped up immediately that led to several delays in shooting. The set itself had been designed by Alan Jones without consulting with director of photography Brian Tufano. Jones then abruptly left the production for personal reasons so that when the set was built, Tufano had still not been consulted during the shuffle to find a new set designer. Tufano had great difficulty in setting up his lights and camera within the small confines of the set. An outside computer graphics firm had been brought in to supply authentic looking medical displays for the many small monitors built into the set. Unfortunately, the computer wouldn’t work right and left a full crew standing around collecting pay while technicians tried to figure out what had gone wrong with their expensive battery of equipment. Later, one of the technicians would quietly tell Russell that an Apple home computer would have been sufficient to give them the displays they wanted.

BEHIND THE SCENES / SPECIAL EFFECTS

“Some of the rough figures from effects companies were just staggering in the amount of money, research and development time they would need.” – Chuck Russell

Chuck Russell was told to shop around for people who could create the film’s extensive special effects and draw up a budget.

“It was very exciting to shop the script around and find out what could and couldn’t be done,” said Russell. “Some of the rough figures I got from effects companies were staggering in the amount of money, research and development time they would need. We just didn’t have the preparation time or budget of something like ALTERED STATES.

“When we found Peter Kuran’s VCE and Craig Reardon, and they got excited about the project, we knew they were perfect for it. They even helped sell the project because of their reputations, Reardon’s for working on Steven Spielberg’s POLTERGEIST and Kuran from his work with George Lucas.”

Russell assigned the live action makeup effects to Reardon, and the miniature and optical work to Kuran’s VCE company. Richard Taylor’s MAGI company was also asked to contribute computer animated imagery for the film’s “Dream Tunnel” effects. For the Dream Tunnel, Russell and Ruben wanted a semi-abstract look different from the other effects work in the picture, a “hazy.” dreamlike look, with an object or two from the upcoming scene to form and float towards the viewer to act as a visual cue for what was about to happen.

The effects sequences were storyboarded by Len Morganti; the budget was finalized on the basis of those storyboards. Because director Joe Ruben had not worked with special effects before, he carefully went through each scene with the storyboard artist.

“I knew that I had to be totally committed to my boards,” said Ruben. “I spent a lot of time thinking through the sequences and how I wanted to shoot them because I knew if I didn’t, the film would go out of control because the special effects people wouldn’t know what they were responsible for and what had to be done with each shot. I was able to get just what I was looking for. Morganti would sketch out something and if I asked him to move it a little lower and more to the right, he’d be able to do it with just a few strokes of his pencil. It was almost like working with a camera.”

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

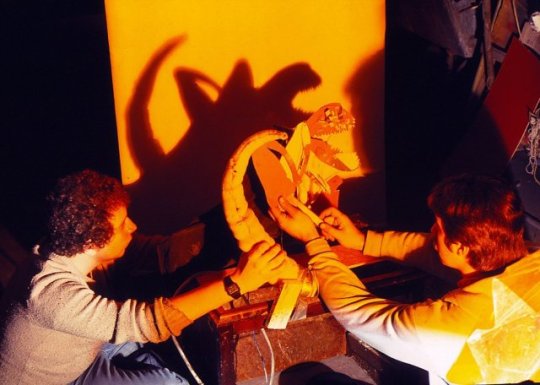

BUDDY”S NIGHTMARE

To try and save money while providing a sense of heightened realism, Russell and Ruben had wanted to shoot the “Buddy” dream, the little boy’s nightmare, on location.

“We found an old Victorian house and were actually shooting,” said Russell. “We realized that by the time you put in the lightning and thunder, it was going to look like Vincent Price was going to come around the corner. It was too on the nose, too traditional. We asked Jeff Stags, our art director, to do something different. He came up at the last minute with the idea of a forced perspective set, sort of Dr. Caligari style. It was a small set, but much more effective, as well as inexpensive. Buddy’s dream is really my favorite because it has much more impact, even though it’s not as spectacular as the last dream.”

Another problem that cropped up involved Reardon’s Snake man suit. Although an impressive work up close, Ruben felt that at even minor distances, it would seem as just a man in a rubber suit. Ruben and Russell still hoped that flickering low-level lighting would help. but Ruben began to realize that even with the extensive work he had put into planning the storyboard angles, the lighting was not going to be enough to sell the suit to an audience. Reardon firmly disagreed, “Contrary to negative thinking about rubber suits, you’ve got to see them as something delightful, and full of potential for doing something wonderful,” said Reardon. “You have to think of them almost as toys. Right when we were about to shoot the basement struggle scene, I went aside with Ruben and said there are two ways of looking at this; you can think of this as a rubber suit which will look bad, or as something which, with the proper angles and lighting, will convince people that they’re looking at a living, breathing, snarling Snake man. Now when Ruben first saw it, he said ‘Oh boy, Reardon, I don’t know…it’s a rubber suit. I thought that had a dangerous ring to it if he really believed it, which was hard to tell because he, Russell, and Loughery had this camaraderie among the three of them based on this constant derogatory kidding. That’s well and good and worth a few chuckles, but where it begins to become pernicious is when it begins to condition thinking to be truly negative.”

Reardon also objected to the low-level lighting strategy that Ruben and cinematographer Brian Tufano used to film the suit. “Tufano seemed to have a fine contempt for any kind of supplementary light which would be, in logical terms arbitrary, but in dramatic terms exciting and interesting … something that would catch the eye, something that would fill in a face or create a little cross light to show textures,” said Reardon. “The naturalistic photography Tufano used can be very detrimental, I think, to SF and fantasy stories. You contrast this with the work of John Hora, who shot THE HOWLING and GREMLINS, and you see that special effects profit enormously from using special tiny spots and direct lighting. But I didn’t feel it was my place to raise the issue.”

Reardon did try to get his viewpoint across to the filmmakers by preparing a lighting test on video. The test was crude but illustrated the alternative Reardon was suggesting. “They ignored it,” said Reardon of the test. “Yet, when they got on the set, they were completely vapor locked on the suit. They didn’t know what to do with it, and they didn’t have any ideas. All the storyboards that had been prepared in advance were completely ignored. Not once did I see anybody bring up a storyboard and crack it open and say that for this frame here we need to set up this angle. All the audacious plans evaporated. Ruben was at a loss to shoot special effects or rubber suits.”

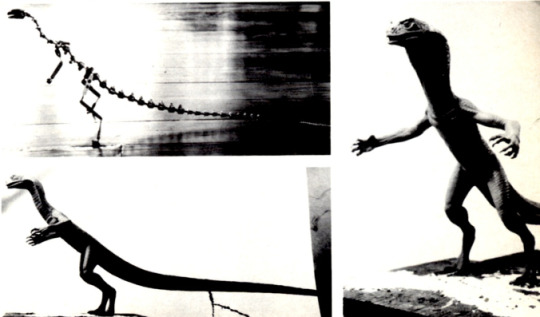

Aupperle s first job was to coordinate the sculpture of the stop-motion Snake man, which was being done by Steve Czerkas, with the suit being built by Craig Reardon.

“They told me that they wanted to feature Craig’s suit prominently, so I was going to try and make the miniature as close as possible to Craig’s suit,” said Aupperle. “We started with a man’s armature and sculpted Craig’s design over it. I knew we were going to have to make some changes, like making the tail longer so it could whip around, but I wanted to avoid one of those instances where the suit never matches the miniature. I’d run back and forth to Craig and measure his design with calipers just to make sure we were dead on.

“Since Craig’s suit was being done in pieces our model was the first time the producers saw the way the design was going to come together. They wanted more changes than I ever expected. They actually had Steve Czerkas re-sculpt the model. It got away from the manlike design and no longer really matched the suit. I was a little concerned that the two would intercut, but that’s what they insisted upon.”

Causing Aupperle the most concern was the production’s seeming lack of respect for the story boards. *They wanted to be able to use Craig’s suit any way they wanted,” said Aupperle. “They didn’t want to be tied down by storyboards. At one time they asked me to revise the storyboards. They said they’d just have to wing it on the set. That attitude left me little to do until they were done with the live action. I found the situation very distressing.”

Perhaps the greatest disappointment for Reardon was the scant use made of a full snake-man costume. The suit appears in the film for just a few frames, as the man-snake breaks through a door; most of the action originally planned for Cedar was replaced by Jim Aupperle’s animation using models built, following Reardon’s design, by Steve Czerkas.

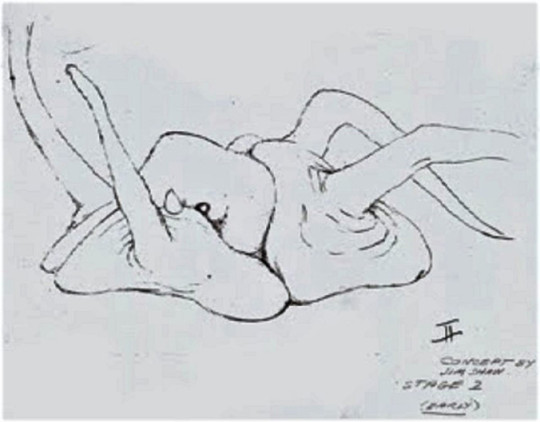

THE SNAKE MAN

Most changes made in the script did not alter Loughery’s story significantly. In Loughery’s original draft, the creature that menaces Buddy in the boy’s dream and later reappears as the creature stalking the President and Alex was to be a rat-man. “We changed that because so much had been done with werewolves,” said Russell. “This was right after THE HOWLING and AMERICAN WEREWOLF IN LONDON and we felt the difference between a man with a rat’s face and a man with a wolf’s face would be minimal.

“We wanted to take a different approach,” Russell continued. “Not the direction of John Carpenter’s Thing but something identifiable, so that when Tommy Ray changed into something to scare Alex, you would be able to see that it was Tommy Ray’s version of the same creature. Joe Ruben wanted to go with something that scared him, and since he’s scared of snakes, we went in that direction. I did some sketches of a snake creature and came up with something that really excited us because it was a departure from anything either of us had seen before. I think part of it came to me from my memories of seeing THE SEVEN FACES OF DR. LAO. When we showed it later to our effects people, Peter Kuran and Craig Reardon, they were really sparked by it too.

A stop-motion animator was the last member of the effects team to be hired, done through VCE. Both Russell and Ruben had agreed early on that the best and cheapest way to get what they wanted from the Snake man sequences would be with a mixture of live-action and stop-motion effects, but they were unsure just how they would mix the combination.

“I knew we would need a good animator,” said Russell. “I knew a live-action Snake man with its long neck and swishing tail would never work in a master shot. We didn’t have umpteen million dollars for physical effects.” Russell and Ruben planned to use low-key, flickering lighting for the sequences in order to seamlessly blend the two effects techniques.

Said Russell, “ Joe and I sat down with the special effects people on the Buddy sequence storyboards, which is the first appearance of the Snake man, and asked which way it made more sense to do it? It made sense to do the wide shots in stop motion and the close-ups in live action, and in the cases where we weren’t sure, we would have both of them overlap and whichever worked better, then that’s what we would go with.”

Although this arrangement was made in good faith and with the best intentions, the decision to let the two techniques overlap and not make a clear distinction between which shots would be assigned to each ultimately proved to be a decision that led to tensions and feelings of betrayal between makeup expert Craig Reardon and the production company.

Opticals were also used to create the clouds and background sky for the first dream that Quaid enters, the vertigo dream where he goes into the mind of a steelworker and falls. “There’s one shot where Dennis Quaid is supposed to be falling. said Kuran. “I spent some time trying to figure out how a person should fall so it will look right on film. We had a good plate of a falling background, and they rigged an elaborate harness at Raleigh to hold Dennis. When we were on the set. Ruben asked me how a person should fall, and I went through the motions of what Dennis should do, but Joe didn’t do that. He told Dennis to do something else that looks really corny. He ruined the shot. There was no way that I could think of to fix it and I think it looks really cheesy right now.

THE PRESIDENTS NIGHTMARES

At a budget of over $300,000 for some 90-odd cuts, DREAMSCAPE was one of the largest jobs VCE had taken on, as well as one of the most difficult. As the producers were continually asking VCE to create more or make changes with what they had done, Kuran wasn’t under pressure to have all the special effects done by the original deadline. Kuran pretty much improvises his effects as he goes along. The more they wanted him to do, the less certain he was about how much longer it would actually take to finish the effects. One thing was certain. There was no way they’d be able to get the movie out in the fall as Russell had originally hoped.

In a way though, the delays had been a good thing; something everyone was almost afraid to acknowledge because of all the tribulations the film had gone through. Kuran was creating the effects layer by layer, and even with only early tests to show, the effects still looked very good. It helped convince Curtis that even though the schedule and budget had gone to hell, it was still within limits he could work with—he was getting a better product for his money than he ever dreamed possible. The more Kuran tinkered with the visuals, the better they got. The live action footage of the actors had come out better than expected, too. Quaid and Von Sydow were marvelous in their roles, and if they could just get the effects to come out anywhere near what had been described in the script, they all began to feel they might have a movie yet, even if they did have to grimace a bit when they realized that the work on the film was still far from over.

Working with Zupnik-Curtis productions was not without its problems for Kuran in the beginning. Because Curtis had never worked with special effects before, he wasn’t sure what to expect.

“We started getting pressure from them early on,” said Kuran. “They had a rough cut of some of the sequences for us to work from, and they wanted to see something. But they kept changing the cutting without realizing that it meant we’d have to go back and redo the whole scene. There was a trolley shot that they wanted to make longer by one foot of film. At that point, all the backgrounds had been shot to length. All the miniatures had been broken down. I managed to talk them out of that one.”

Another problem is the very nature of post-production work. “When somebody does a movie, they make a little mistake here and a little mistake there, and if it doesn’t work, they just kind of throw the shit over their shoulders and it lands on them in post-production,” said Kuran. “Unfortunately, this is where we do most of our work. People are at their worst to deal with in post-production. They’re under deadlines, and if the movie doesn’t work they’re in even worse shit. The people who shot the movie are gone and they usually refuse to accept the fact that the movie is crummy because of them. Lots of people can go onto a production and create a lot of shit and come off smelling like a rose because the movie’s not finished when they leave it.”

Although VCE was contributing some 90 cuts to the film, the majority of the effects were going to be clustered around the holocaust dream near the end, and at the start, including the terrific A-Bomb teaser which opens the film. “I thought the bombs in THE DAY AFTER just didn’t look right,” said Kuran. “They looked so dark and cold. You look at a nuclear test and you can see it’s a very bright fireball, so we wanted a very hot look to our bomb.”

The Trolly/Subway Cart

Reardon’s and Kuran’s most elaborate work is seen in the climactic sequence, a surreal view of the day after Nuclear Armageddon. Dennis Quaid enters a dream which represents the President’s worst fears of nuclear war, the setting is an old trolley car that travels among the bombed-out ruins of Washington, D.C., past several surrealistic tableaux-travelling mattes and miniatures courtesy of Peter Kuran’s V.C.E. David Kelley, Plummer’s henchman, enters the dream as well, for a climactic confrontation with Quaid.

For the holocaust dream at the end, Kuran’s basic effects strategy was to have a live-action foreground element, an intermediate miniature behind that, and then have a matte or tinted water tank shot as the background. The scenes were difficult because Kuran needed something that would convey a sense of extremely large scale while still having realistic detail, a tall order on the show’s tight budget.

Russell had originally wanted to do the holocaust effects scenes first and rear-project them as they were shooting the live action. Kuran pointed out that it would take thousands and thousands of feet of film to try and generate the footage they would need, and that they would have a better chance of making sure the background footage matched with the live-action trolley car if they shot the trolley first and then had it to play the backgrounds against.

“Jim Belohovek and Sue Turner built the miniatures for the scenes, and we photographed them in different layers,” said Kuran. “To get good depth of field, we shot them at one frame per second. Then we started adding the fires. Because those had to be slowed down, we shot them at 72 frames a second. We don’t have any motion control equipment. I set up a dolly for the camera, filled the room with smoke, then lit the fires. It takes a couple of seconds to get the camera up to speed. Then we pushed the dolly down the tracks until eventually timed the push right and got it to look the same speed that we thought the trolley would be moving at. The background is a water tank shot that we used to make it look moody by adding some glows and fires. Counting everything I’d say there’s about 20 elements in that shot.”

While Kuran labored in the bowels of VCE, director Ruben and Academy Award winning editor Richard Halsey were slowly cutting the film together using unfinished optical tests that were the right length and Jim Aupperle’s Snake man animation. Kuran had been able to find them an east coast underground filmmaker named Dennis Pies (pronounced “pees”) to do the Dream Tunnel effects and the stuff looked wonderful. It was exactly what they wanted. But now it was time to decide how they were going to mix the live action Snake man and the animation, and to a great degree, they were coming down against the live action footage.

With the will to manipulate the dream to his own ends, Kelly at one point extends his fingernails into stilletos, which he uses to rip the heart from the car’s conductor, with the logic of dreams, the trolley then becomes a subway car, populated with a dozen grisly war victims, looking more dead than alive, Shortly after, Kelley transforms into a snake monster.

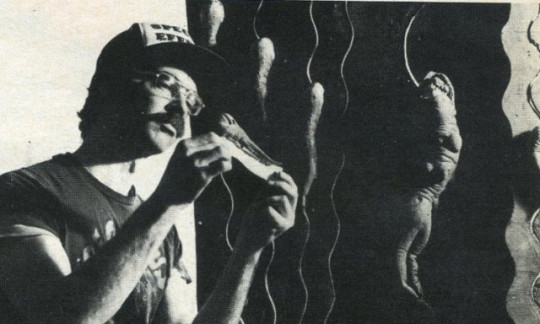

Reardon details the other effects he did for Dreamscape. “Tommy Ray Kelly transforms with knives springing from his fingers. He uses these to tear out someone’s heart which sits beating in his fingers,” the effects Technician says. “We made a prosthetic hand and an artificial heart for this scene.

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

“We made 12 mutants up for them, Reardon says of the subway denizens, “all extremely exaggerated in their ugliness, so that, in the heavy shadows and flickering light that was planned for the shot, they would still prove effective. The design is heavy-handed, but suitably macabre for the scene.

“I hogged all the major sculpture on the picture for myself, but there were a number of other people working with me on this that also deserve mention. My greatest praise must go to Bruce Kasson, who took the weight off my shoulders where mechanical work is concerned. He worked out the mechanical effect used for the death of one of the characters at the end, as well as the stilleto fingernails. David Miller was our acrylic man, doing all the hard plastic pieces, and certainly one of my right hand men in doing the sculpture, along with David Cellitti.

Snake Man Transformation Effect

Following the completion of principal photography, there was a brief hiatus, during which Reardon re-stirred his somewhat-dampened enthusiasm, before tackling the transformation sequence.

Replacement animation is a variety of stop motion that uses separate, slightly differing sculptures, rather than the movable models most frequently associated with the form. Pioneered by George Pal, replacement animation is nowadays seen mostly in David Allen’s television commercials featuring such animated characters as Mrs. Butterworth and the Pillsbury Doughboy. Reardon’s suggestion to try this technique for an unusual transformation. Because of the frame-by-frame nature of the animation process, the sequence would be a short one-less than two seconds in sculpting work than Reardon (or, most likely, anyone else) had ever expended on a transformation effect of such short duration; 32 heads, each altered slightly from the previous head in sequence, each making a barely more than subliminal appearance in the film. It was this rapidity, and the violence of the change, that Reardon felt would make it entirely unique.

“The major problem was one of time,” Reardon says. “How was I to produce 32 different heads for this sequence within a reasonable schedule? The first thing you want to consider in a situation like this is, can you do it full-size? It took me about 15 seconds of heavy thought to realize that would be a killer, because of the molds that would be involved, and the sheer awkwardness of doing such an extensive sequence in full scale. From the beginning, they wanted David Kelley’s features discernible in the snake head’s face, so l also briefly considered taking a cast of Kelley’s face and using reduction techniques, like special shrinking molds, to bring it down to scale-but there is enough distortion in the reduction process that it wouldn’t likely be worth the effort. So I finally decided on doing a miniature portrait sculpture based on his features.

“One way to have gone would have been to produce molds of each and every stage cast one head, alter it a little further, make a mold from that and cast another stage. I ruled that out; it takes about a day to make one mold, so it would have taken a full month to prepare for the sequence.

“Instead, I took a master mold of the first stage turned out a dozen or so duplicates of that, and altered each of them to cover the first third of the total transformation. I then made another mold from the last of these, and changed those progressively. That way, I had to make no more than three molds. As the work progressed, I did some rough tests on video, which helped to show up a number of small glitches. Some of these proved very difficult to correct-seen side by side, two heads might appear to match perfectly, but tiny variances would show immediately on video.”

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

A chief problem with all stop motion effects is that of temporal aliasing,” a term used to describe the unnatural look of objects seen to be in motion, but not blurred as they would be if actually filmed in real-time. All along, Chuck kept saying, ‘I hope this won’t look like animation,” says Reardon, “and of course all I could say was, I hope so, too.’

“Jim Aupperle, who did the stop motion animation on the snake monster, and my friend Randy Cook, made some suggestions to counter that problem. Both suggested that if each stage would be slightly dissolved into the next stage, that would soften the edges, and disguise whatever anomalies there were from one head to the next. So Peter took the negative and a dupe negative, printing them to a single positive with overlapping frames, so that no single frame gives a really razor sharp image of one sculpture.

The Caves

Another kind of problem arose in shooting the climax of the President’s holocaust dream, set in a cave-like underground grotto decorated with fires, twisted girders and a glowing pool of green water. Originally it was planned to shoot the scene on a section of the ruins” set at Raleigh Studios. But Russell found out that he could get a few days shooting time at Bronson Canyon. The site, long a favorite locale for low-budget productions, is actually a short “Y” shaped tunnel through a jutting canyon wall in the nearby Hollywood hills. Open at all three ends and with a high ceiling, Ruben and Russell felt they could put up a more effective set inside the cave at relatively little cost to the production.

The art department scrambled on something like 48 hours notice to come up with a revised set for the cave. They did well, but lighting the set so that the lights themselves wouldn’t show was a difficult task made harder by the fact that creating the pool of water just past the junction of the “Y” in the cave had turned the rest of its sandy floor into gritty muck that forced the crew to support the lights and camera on wooden planks and sandbags the best they could. Working in the enclosed confines quickly turned miserable too. Brian Tufano, who had been hired because of his work on QUADROPHENIA and THE LORDS OF DISCIPLINE, is yet another British cinematographer who likes to use smoke to diffuse his lighting to give the set greater visual depth. Every time Ruben went for a take, Tufano’s assistants would pump the small, sealed cave full of hot, oily smoke and wait to see if the density was right. While the crew and stars quietly gasped behind their respirators, either more smoke would be pumped in if it wasn’t enough.

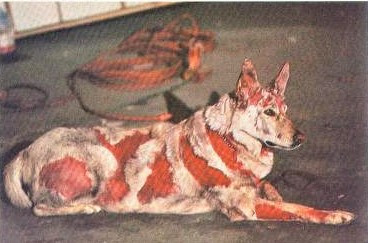

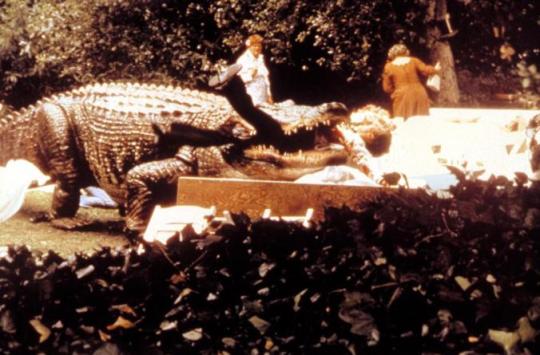

According to Craig Reardon, the first scenes that were supposed to be shot in the caves were thought to be relatively straightforward. Quaid, followed by Albert, is moving through the cave when they are attacked by a mutant dog. For the dog’s costume, Reardon’s assistant, Michiko Tagawa, had made some wonderfully revolting costumes.

“They were beautiful.” Reardon said. “They had entrails bulging out of the body and exposed rib cages and boils and french fried skin. Now we were told that a Doberman would wear the costume, and in fact, the trainer had auditioned the dogs in a costume they worked in on the BUCK ROGERS television show. So Michiko went to a great deal of trouble to measure the Dobermans and I contributed sculptures for the heads while she built the body parts up from reject castings for the subway zombies.” Once we got them suited up at the Bronson location however, the Dobermans refused to perform.

“The dogs trouped around in the mud and the zippers and their fur got packed with it,” said Reardon. “It was a disaster. They took one of the suits and tried to put it on a German Shepherd, a dog which is considerably different in body build.”

In his big scene the dog was supposed to run a short distance and jump at Quaid. In take after take however, the dog merely trotted up to Quaid and stopped at his feet to try and shake the costume off. Eyes turned on the dog’s embarrassed handlers who quickly explained that the dog usually didn’t act like that; it was probably because he felt uncomfortable with the costume.

Reardon snipped parts of the costume’s legs away, hoping to make it more comfortable, but this produced no better reaction. Next, the dog’s owners took to furiously waving a little furry target at the dog. then quickly sticking it just inside Quaid’s shirt while everyone enthusiastically urged the dog to attack. This made the dog think everyone just wanted to play. It would run up to Quaid, half-hop once, then bark excitedly while waiting for his trainers to get the toy again.

Quipped Reardon, Bruce Cohn Curtis said the mutant dog looked like someone’s dirty laundry running across the floor.” Finally the dog made one decent leap past Quaid and Ruben called it a take. The shot is still in the film, although the rest of the mutant dogs were replaced with German Shepherd with their fur shaved in patches and dabbled with red goo.

“The script also called for these two raggedy dogs to chase after Quaid and Albert in the dream. It seemed that the easiest way to achieve a really striking appearance for the dogs would be to suit them in a costume covered with foam latex. I consulted with the trainers on the feasibility of it, and they said

‘Yeah, sure.’ So l sculpted two mutated dog heads, and Michiko Tagawa, a very good craftsperson who’s done work with Winston and Burman, did a beautiful job on the body suits-really hideous and nasty. She took some reject castings from the subway mutants, and reworked them into twisted body shapes, warped, burned and decked with growths. But the dogs wouldn’t wear them, and the trainers sort of shrugged, and said ‘What do you expect?’

“Those trainers were let go, and replaced by Karl Miller, who allowed them to shave his dogs in erratic patches, and we gobbed all kinds of blood, goo and crap on them. Good enough, but it’s unfortunate that Michiko’s suits will never be seen.”

VCE generated the bits and pieces that would help add life and highlights to the live action effects. A red glow was added to the mutant dog’s eyes, as well as crawling purple electrical effects when the dogs vanish. Opticals materialized David Patrick Kelly’s nunchaku weapons smoothly into his hands as well as allowed Dennis Quaid to heal his wounds and transform himself into Kelly’s father.

Snake Man Showdown

The next scene planned for the cave involved Quaid and Albert, discovering it is a dead end and that the Snakeman is right behind them. It comes out of a side tunnel, snarls, and attacks Quaid. Ruben decided he wanted to use the full-sized Snakeman suit for the shot, and Reardon was given short notice to get it ready. At the time, Reardon was working full tilt to prepare the suit needed for the basement struggle in the boy’s nightmare. A different head would be needed for the cave sequence.

“Russell got a hold of Bronson Canyon and said we’ve got to do the Kelly head to look like David Patrick Kelly, playing the President’s assassin) right away. You can’t change things around like that. I said I’d try when I should have told him no.”

Ruben shot Reardon’s live Snakeman suit in the cave, although eventually discarded most of it and replaced the scene with a stop-motion cut. Also discarded was a small but important effect Reardon had worked very hard on getting right, a brief shot where Dennis Quaid “heals” a wound in his shoulder.

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

“We created a sort of bite effect, then put a plastic membrane over it and melted it with a plastic solvent so that when they ran the film backwards, the wound would heal,” explained Reardon. “It didn’t work as well as it did on the bench, which is frequently the case, but you did get a feeling of the actual fleshy material knitting itself. They opted to have Peter Kuran redo it with animation.”

More successful was a Reardon designed effect where Kelly, now distracted by an ingenious ploy of Quaid’s, reverts to a half-human, half-snake form. While diverted, Albert sneaks up behind him and drives a length of pipe through Kelly’s chest. For this shot, Reardon made a false chest with a mechanical rubber pole section inside that was connected to a spring and operated by cable. Albert would sneak up holding the pipe, then drop it out of camera sight as he lunged for Kelly, and the rubber pipe would burst through a section of painted tissue paper. Although the complex mechanical effect took some time to rig, it was accomplished in only three takes and is gruesomely realistic. It made for a happy interlude before the crew was to run into yet more problems once they left Bronson Canyon and returned to Raleigh Studios.

Dave Millers Unused Snake Man

“I also worked on a snake man head, the one that was originally going to be in the elevator sequence, emerging from the head of Dennis Quaid. But then, they had some kind of quibble over Craig’s head of Quaid–they said it didn’t look like him, or some such garbage-and they hired Greg Cannom to do that sequence over. Greg did another head of Quaid, which they wound up not even showing, though it looked perfect, and another snakeman, which-sorry, Greg I didn’t care for too much. It didn’t seem to have much definition; it was hard to tell what it was. Plus, it was pretty badly edited.” – David Miller

BOB BLAIR’S DREAM DEMISE

The “Buddy” dream completed the bulk of the main shooting. DREAMSCAPE moved from the largest soundstage at Raleigh into one small stage for what was hoped would be the final shot of the would grasp what was happening. Because Quaid’s strike against Plummer was to be a surprise, Ruben and Russell felt it was absolutely necessary to make sure that the lighting look realistic right up to the moment of the attack. This meant shooting the effect not with lighting that would highlight the makeup, but with ordinary florescent lighting. Reardon hated the lighting, but went along with Ruben’s insistence that changing the lighting would tip-off people that something was about to happen.

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

About a month earlier, in late June, Reardon had supplied a transformation head, known as a “change-0” head in the business, for a scene late in the film in which Dennis Quaid confronts political schemer Christopher Plummer in the one place where Plummer is vulnerable, inside Plummer’s own dream. Quaid borrows a trick from dream assassin David Patrick Kelly and changes into his own version of the Snakeman before killing Plummer. The effect was planned to first show Quaid’s head beginning to change, cut back to Plummer as the Snakeman’s hands shoot out for his throat (a very brief scene which was shot earlier) then a quick cut back to Dennis Quaid’s Snakeman head coming for the camera.

“We prepared a head, which I felt was better than a lot of THE HOWLING heads,” said Reardon. “We didn’t content ourselves with just having the face bulge out. We had the eyes blink, and when they opened they were snake eyes. At the same time the neck elongated and the cheeks distended, and the eyes began to pop out of their sockets. The mouth opens unnaturally wide and the teeth elongate. But nobody liked it. Ruben said to me, ‘Geez Reardon, I expected something like AMERICAN WEREWOLF IN LONDON.’ That’s great. You give me six months and six hundred thousand dollars and maybe you could get that. Besides, that effect was five different heads. I told them all along that I was only going to come up with one head and do as much with it as I could.”

Neither Russell nor Ruben had been happy with the head when Reardon had brought it in. Under the flat lighting of the elevator mockup, the hair looked too bushy and still, the face too lifeless, and the neck far thicker than Quaid’s. The head didn’t work well either. with eyes that frequently jammed as they started to roll up. It took several takes to get the mechanism to work right. But beyond that, when Ruben and Russell saw footage of the effect, they realized that what they thought would be a good visual just wasn’t that exciting.

“Forget that it wasn’t convincing on film,” Ruben said. “When I saw it, I just realized that we needed a more shocking effect.”

“It wasn’t exciting enough,” added Russell. “We didn’t realize that until we saw it. It was a subtle effect that just wasn’t explosive enough. Craig’s head didn’t show anything either that would connect it with the Snakeman, and we decided we needed that, so we racked our brains and decided on something simple, like a guy’s head ripping apart with the Snakeman’s head coming out of the pieces.”

Russell contacted Reardon, but by this time, Reardon was both fed up with the production and busy trying to finish the replacement animation for David Patrick Kelly’s Snakeman transformation so he could be done with the film. Since Reardon was busy, Russell had to find someone who could do the effect and do it quickly. He decided on Greg Cannom, a former assistant to Rick Baker and Rob Bottin. Cannom’s first solo assignment was THE SWORD AND THE SORCERER, and more recently he assisted Baker with the apes for GREYSTOKE.

Cannom had talked with Russell about a year before DREAMSCAPE about another film project that never went through. Cannom was interested in the assignment, but checked with Craig Reardon first, before committing himself. Reardon gave his blessing. Cannom went into his workshop and tried an effect which would combine the two concepts that Russell discussed, creating a skull that would not only split apart, but split apart and turn into a monster at the same time. “I could see the use of the Snakeman with the kid’s nightmare, but going into an adult’s nightmare, I thought it should be a lot more horrendous and scary,” said Cannom.

Cannom’s first prototype makeup was deemed unacceptable by producer Bruce Cohn Curtis. It was a bitter decision because of the amount of effort Cannom had put into it. Cannom took a fiberglass skull which he cut and hinged so it could be pulled apart. Inside the skull, Cannom used a soft foam and sculpted a hideous face so that when the skull was pulled apart, the jaw would drop down and the foam face would come out to form the monster.

“I loved Cannom’s first approach,” said associate producer Chuck Russell. “I think it was terrific. The dangerous thing about the makeup was that in a very quick cut, with a man splitting his head open and something gooey, dark, and spongy coming out, it might look like brains. It was hard to argue for it because of that.”

Curtis told Cannom that they wanted something closer to Reardon’s Snakeman concept. Cannom tried to figure out how to fit Reardon’s Snakeman design into a reworked version of the splitting skull but finally gave up and settled for a two-piece approach. Cannom first built a small, embryonic Snakeman head which would be moved like a hand puppet inside the skull after it split apart. Cannom wanted to stop the camera and replace the small head with a fullsized but slimmer Snakeman head that would rise out of the neck and lunge for the camera dripping goo and skin. As with Reardon before him, Cannom was less than happy with the treatment he felt his makeup got from Ruben and Curtis. Assisted by Jill Rocklow, Kevin Yagher and Brian Wade, Cannom did the effect, but felt little enthusiasm for the final product.

“Bruce Cohn Curtis and the other producer, Jerry Tokofsky, were so insulting and rude to me it was incredible,” said Cannom. “It was like they already had something against me and wanted to find fault. I never want to see Bruce Cohn Curtis again.

“I don’t really think my effect works either,” added Cannom. “It’s not done the way we wanted to set it up. We were very careful about it. First, the skull would split apart, then we would cut away, put the snake creature back into the neck and put skin all around it, and then have it come at the camera. I spent hours getting the chicken skins for the makeup and preparing them, then setting-up the effect. Ruben looked at it and said, ‘That’s not what I want. No neck and no skin. I just want the head coming at the camera.’ I told him that didn’t make any sense! But that’s what he wanted, so we did it his way.”

POST PRODUCTION

Because Ruben and Halsey had been able to do much of the editing work while the final opticals were being generated, the final scoring and assembly of the footage was completed quickly. Curtis had a finished film only a month later and premiered it to his friends in mid-January at a small mixing theater in Hollywood. Although there were some clunky spots that hadn’t been fixed because of time and budgetary problems, the final cut was deftly edited around most of them and they were visible only if you knew what to look for. The audience gave the film a big hand and Curtis was very happy, as well as Kuran. Russell, Ruben and Loughery, who now looked forward to having a potential hit associated with their names. Although Craig Reardon liked the film, he was still unhappy with director Ruben.

Ruben defended his decision to replace Reardon’s work. “Craig was under tremendous pressure to deliver an awful lot of complicated physical effects,” said Ruben. “I wouldn’t be able to see a finished physical effect practically until the day we were ready to shoot it. That was a rough way for both of us to work. I was disappointed some times, and I’m sure he was disappointed in the way I was shooting things, although at no time can I remember him making specific suggestions. I think that the main thing I would change if I were to do it again, and I wouldn’t mind working with Craig again.

youtube

Dreamscape (1984) Music by Maurice Jarre

01.DREAMSCAPE 2:58

02.THE JOURNEY 4:22

03.FIRST EXPERIMENT 1:55

04.SUSPENSE 2:09

05.JEALOUSY MERRY-GO ROUND 2:56

06.THE SNAKEMAN 1:08

07.ENTERING THE NIGHTMARE 4:17

08.LOVE DREAMS 4:10

REFERENCES and SOURCES

Twilight Zone v04 n01_

Fangoria 44

Fangoria 27

Fangoria 34

Fangoria 39

Cinefantastique v15 n02

Dreamscape (1984) Retrospective SUMMARY Alex Gardner (Dennis Quaid) is a psychic who has been using his talents solely for personal gain, which mainly consists of gambling and womanizing.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

SUMMARY

In the film’s prologue, two geological researchers for the American multinational corporation NTI encounter an ancient alien laboratory on Titan, the largest moon of Saturn. In the lab is an egg-like container which is keeping an alien creature alive. The creature emerges and kills the researchers. Two months later, the geologists’ spaceship crashes into the space station Concorde in orbit around Earth’s moon, its pilot having died in his seat.

CREATURE, 1985

NTI dispatches a new ship, the Shenandoah, to Titan. Its crew, consisting of Captain Mike Davison (Stan Ivar), Susan Delambre (Marie Laurin), Jon Fennel (Robert Jaffe), Dr. Wendy H. Oliver (Annette McCarthy), David Perkins (Lyman Ward) and Beth Sladen (Wendy Schaal), is accompanied by the taciturn security officer Melanie Bryce (Diane Salinger). While in orbit, the crew locate a signal coming from the moon—the distress call of a ship from the rival German multinational Richter Dynamics. Their own landing turns disastrous when the ground collapses beneath their landing site, dropping the ship into a cavern and wrecking it. When radio communication fails, a search party is sent out to contact the Germans.

In the German ship, they find one of the containers from the prologue breached, as well as the dead bodies of the crew. The creature appears and kills Delambre when she lags behind the escaping group. Fennel enters a state of shock at the sight and Bryce sedates him. When they return to their own ship, the Americans find that one of the Germans, Hans Rudy Hofner (Klaus Kinski), has snuck aboard. He tells them how his crew was slain by the creature, which was buried with other organisms as part of a galactic menagerie. He proposes returning to his ship to get explosives, but the crew are unwilling to risk it.

It becomes apparent that the creature’s undead victims are controlled by the creature through parasites. Unsupervised in the medbay, Fennel sees the undead Delambre through a porthole and follows her outside. She strips naked, and he stands transfixed while she removes his helmet. He asphyxiates, and then she attaches an alien parasite to his head. Now under alien control, Fennel sends a transmission to his crew mates, inviting them over to the German ship. Hofner and Bryce are sent to get some air tanks for the Shenandoah and stand guard over it, while the rest of the crew go over to the Richter ship.

Hofner and Bryce stop over at the menagerie on their way, and are attacked by Delambre, who has had a parasite attached earlier. The rest of the crew go over to the Richter ship, and find Fennel with a bandage on his head to conceal his parasite. Davison insists that medical officer Oliver examine his head, so Fennel has her accompany him to the engineering quarters to feed her to the creature. Davison and Perkins notice Fennel doesn’t sweat and go check on them. They are too late to rescue Oliver, who is decapitated by the creature, but Perkins blows up Fennel’s head with his pistol.

Soon afterwards, Sladen runs into an infected Hofner. She escapes the ship, and in her haste, only puts on her helmet after exiting. Perkins spots her outside and opens the airlock. Now unconscious, Sladen is carried in by Hofner to lure the others. They fight, and Davison manages to defeat Hofner by ripping off his parasite. The three survivors formulate a plan to electrocute the creature with the ship’s fusion modules, which can only be accessed by going through the engineering quarters.

Alarms suddenly sound as a creature makes its way through the ship, committing sabotage. Sladen and Davison go through engineering to construct an electrocution trap, while Perkins goes to the computer room to monitor the creature. Sladen finishes rigging the trap just in time for the creature’s arrival, and they apparently electrocute it to death. However, when Davison leaves, it captures Sladen.

CREATURE, Robert Jaffe, Klaus Kinski, 1985

Davison and Perkins follow her screaming and find her locked inside engineering. Studying the ship’s blueprints, they find another entrance to engineering and sends Perkins to lure away the creature while Davison retrieves Sladen. On the way, Perkins locates one of the bombs Hofner had mentioned, just before the creature jumps him. Dying, Perkins manages to attach the bomb to the creature and set off the countdown so Davison can jettison it through the airlock.

It climbs back aboard, however, so Davison tackles it, throwing himself out the airlock in the process. When the bomb fails to explode, Bryce appears and shoots it, which sets it off and kills the creature. She recovers Davison and dresses his wounds, then they reunite with Sladen and finally launch the ship.

Director William Malone

BEHIND THE SCENES/ PRODUCTION

Even though in space, nobody can hear you scream Bill Malone still wants you to try. The 37 year old director of SCARED TO DEATH is getting ready to try and scare audiences again with his second feature, THE TITAN FIND. The $4.2 million production is set to open this spring, and Malone is cautiously optimistic about its chances.

The film is set in the near future, when the commercialization of space is well under way. On the surface of Titan, a research ship has discovered the remains of an ancient alien laboratory and its collection of specimens. One specimen, however, turns out to be much livelier than originally thought, and kills all but one of the crew. The survivor lives long enough to make it back to Earth, setting off a race between two competing multinational firms for whatever is there, both unaware of just how deadly the alien is.

Despite its small budget, the film boasts good production values, with set design by Robert Skotak and effects by the L.A. Effects Group, and stars international weirdo Klaus Kinski as a German space commander.

Malone, a baby-faced man who resembles DREAMSCAPE’s villain David Patrick Kelley, explained the roundabout way THE TITAN FIND got off the ground. “After I did SCARED TO DEATH, I was trying to get another project going.” said Malone. “One of the people my producer Bill Dunn and I went to see said they’d really like to make a picture like SCARED TO DEATH. They signed us up to do one of our projects, MURDER IN THE 21ST CENTURY, a detective story. After we did the screenplay, they didn’t think it had enough exploitation value. ‘What else do you have,’ they asked, and can you have it to us by tomorrow morning?’ This was in January, 1984.

“On that short a notice, all I could do was go through my files and see what I had kicking around. I found a two page story synopsis of THE TITAN FIND which I had written six or seven years earlier, and I took that in to them. It was basically just the beginning of the picture as it is now. I read it to them with some background tapes of classical music and they loved it. I said to myself, ‘Great…, now how do I make a film out of this?”

Not only was how a problem, but where as well. With a tight budget and little lead time given the company, it would have been nearly impossible to get studio space to shoot the film. The production’s answer was to create its own studio, setting up shop in an abandoned industrial plant in Burbank. The small warehouse became a tight maze of different bits of spaceship interiors and planet exteriors, with Malone’s crew shooting on one set, while another was torn down behind them and another built just ahead of them. Filming began June 25th.

Construction of the bridge of the NTI spaceship ‘Shenandoah

“We’ve been on it now for 8′ weeks, and I’m tired,” said Malone. “This has been a particularly tough picture because everything’s got smoke and dust and lava rock, which not only creates a lot of noise when you step on it, but makes this gritty dust and gets into everything. We’re forever wearing filter masks. Initially it sounded like a good idea doing everything in one location where you wouldn’t have to be moving people around, but after a while, all you want to do is go outside and see some sun.”

Malone is taking a lot of liberties with the Titan setting. “Well, I figure it will be a long time before anybody gets there to find out what it is actually like,” he said. “Everything’s got this sort of Dante’s Inferno look to it. There are these tremendous lightning storms going on all the time. The picture almost winds up looking like gothic horror. In fact, when we designed the miniatures, that was the instruction, make them look like Dracula’s castle. From the dailies, someone said they thought it looked like a Mario Bava picture, which I take as a compliment.”