Photo

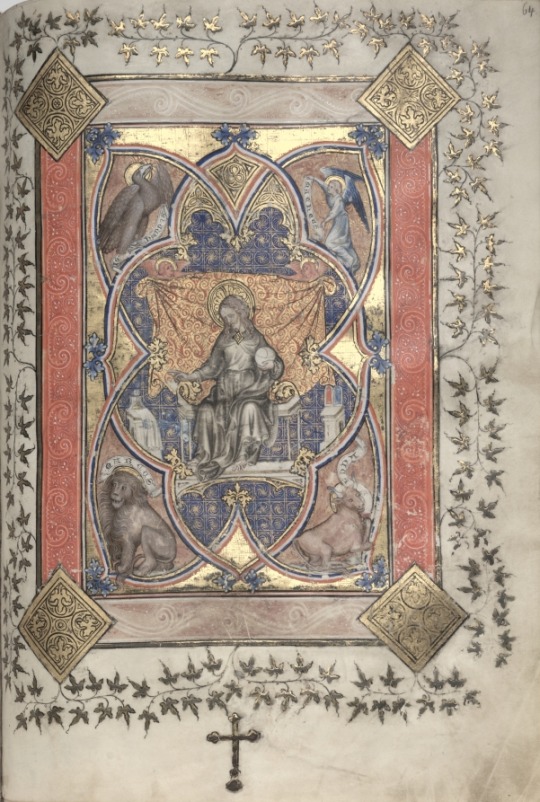

The Gotha Missal: Fol. 64r, Christ in Majesty, Master of the Boqueteaux, c. 1375, Cleveland Museum of Art: Medieval Art

This elegant Latin manuscript is known today as The Gotha Missal after its eighteenth-century owners, the German Dukes of Gotha. The volume was originally copied and illuminated in Paris around 1375 – a commission of the Valois king, Charles V “the Wise” (1364-1380), one of the great bibliophiles of the fifteenth century and brother of Dukes Philip the Bold of Burgundy and Jean de Berry. Manuscript missals were not intended for the lay user, but rather for the use of the celebrant at Mass. The present volume was therefore meant to be used by the king’s private chaplain and was probably housed in Charles’s private chapel, possibly in his principle residence, the Palace of the Louvre (demolished in the sixteenth century). The main decorative body of the missal consists of two full-page miniatures comprising the Canon of the Mass and twenty-three small miniatures. The style and high quality of the decoration points to its inclusion withing a select group of manuscripts accepted today as from the hand of Jean Bondol. Bondol was active at the court of Charles V from 1368 until 1381 where he headed the court workshop and also served as the king’s valet de chambre. The blind-tooled leather binding dates to the fifteenth century.

Size: Codex: 27.1 x 19.5 cm (10 11/16 x 7 11/16 in.)

Medium: ink, tempera, and gold on vellum; blind-tooled leather binding

https://clevelandart.org/art/1962.287.64.a

265 notes

·

View notes

Text

0 notes

Photo

Tabula (Square) with Vine Scrolls Containing Aquatic Birds, Metropolitan Museum of Art: Islamic Art

Gift of George F. Baker, 1890 Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY

Medium: Wool, linen; plain weave, tapestry weave

72 notes

·

View notes

Photo

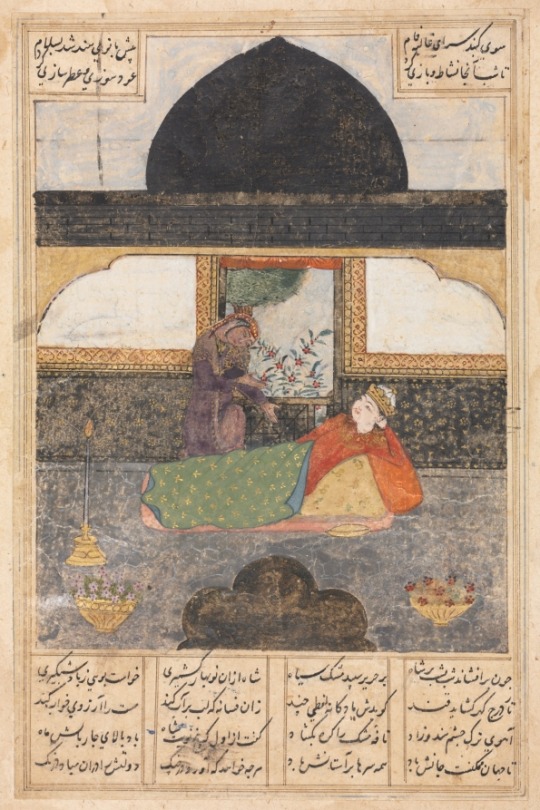

Bahram Gur Visits the Princess of India in the Black Pavilion (recto): Illustration and Text, Persian Verses, from a manuscript of the Khamsa of Nizami, Haft Paykar [Seven Portraits], c. 1400-1410, Cleveland Museum of Art: Islamic Art

The Khamsa, a suite of five poems written by Nizami in the 12th century, recounts the history and legends of pre-Islamic Iran with an emphasis on love rather than war. Here, in an early extant depiction of a favorite story, Shah Bahram Gur visits a princess in a black pavilion; this is one of seven paintings depicting the king visiting one of his seven wives, each in a different colored pavilion, on successive days of the week. The princess is shown telling a story after a day of lovemaking.

Size: Image: 18.7 x 12.3 cm (7 3/8 x 4 13/16 in.); Overall: 23.2 x 15.5 cm (9 1/8 x 6 1/8 in.)

Medium: opaque watercolor and ink on paper

https://clevelandart.org/art/1944.486.a

117 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Christianity in Africa Jesus in the Morning, Voodoo in the Evening

The old natural religions continue to thrive in Africa. While Christianity and Islam vie for supremacy in many countries, they have failed to banish the rain gods and spirits south of the Sahara. Frequently the pagan rites have fused with a faith in Jesus Christ.

Six men in flowing white robes stride across the square in Maryal Bai. One village elder, his features gnarled, is wearing a leopard-skin hat. Akoon Duong is a priest, as are his five companions. To demonstrate his spiritual power the old man brandishes an elaborately carved spear, as do the other “spear masters” - the high priests of pagan nature worship. Akoon Duong has inherited these trappings of power from his grandfather, who in turn had received them from his own grandfather.

The men thrust their spears into the muddy ground and dance. One of them pounds out the beat on a bush drum. Scrawny arms flail upward, quivering in ecstasy. They render their songs in high, reedy voices. If there were a drought, they would have had to invoke Deng, the rain god. But this is the wet season; malaria can strike at any time, so they pray for deliverance from disease.

Maryal Bai is in southern Sudan, 15 miles from the no-go area between the Islamic government’s militias and the guerrillas of the Sudan People’s Liberation Army (SPLA). The village was the demarcation line for the recently ended North-South war and the escalating conflict in Darfur.

Just a few miles to the north, Sharia law - with its punishments extending from whipping to dismemberment - prevails. The South is mainly inhabited by Christians. For decades the region has been ravaged by fighting. Usually over matters of faith.

Camped along the majestic Gazelle River are thousands of refugees, the sableskinned, long-legged people of the Dinka tribe. Once they had fled to Darfur from the war in the South; now they are returning to the lands of their ancestors.

Time has stood still

The clash of civilizations and religions, the focus of so much debate in Europe and America, can be witnessed firsthand here in Africa. And today Maryal Bai is one of its many fronts. Islamic Fundamentalism is advancing from the west, penetrating all the way to the continent’s eastern reaches. In some regions it collides head-on with an equally aggressive brand of Christianity. The clashes are becoming increasingly bitter because the desert is expanding, bringing more poverty in its wake. According to Georg Brunold, a Swiss expert on African affairs, a front line is crystallizing here that will spark “decades of war.”

Yet, as hard as the two great monotheistic faiths have struggled for supremacy, they have failed to wrest power from priests like Akoon Duong. With its nature deities, the old African mythology is often the only stabilizing force in a world full of suffering, displacement and death, where everything is in constant flux but rarely changes for the better, where - in many respects - time has stood still. This is a world populated by nymphs and sirens, by elfin spirits, sun and moon gods, and by animal deities such as cows, stags, lambs and calves.

At the end of the 19th century, the British ethnologist Edward Burnett Tylor coined the term animism (the Latin word anima means soul or breath) to describe this pantheon, correctly assuming that plants, animals and objects also have souls in the minds of these “primitive peoples.”

Cult of the dead

Despite the best efforts of Christian and Islamic missionaries, some 40 percent of the people in Burkina Faso, western Africa, are still considered animist. In East African Ethiopia, a largely Christian domain, the figure is still thought to be 10 percent. Yet these numbers remain pure conjecture. In truth, religious distinctions have long blurred, indeed evaporated, in Africa. Someone who attends church in the morning and the mosque at midday might easily invite a voodoo priest over in the evening to read the kola nuts.

DER SPIEGEL

Sub-Saharan Africa.

Practically everywhere the cult of the dead intermingles with Christianity, according to religious scholar Fritz Stenger from the Catholic University of East Africa in Nairobi. “There is scarcely any distinction between the secular and religious spheres; faith is omnipresent,” says Stenger.

Should a child succumb to malaria, the relatives - according to Stenger - would partly blame the lack of effective medicine. However, the belief that its death was willed by God would carry greater weight. It is therefore no surprise that doctors attending to the sick often arrive with the preacher, medicine man and local sorcerer. Stenger, who has spent more than three decades in Africa, has observed this coexistence of divergent faiths throughout the so-called “Dark Continent.”

In Kenya, for example, the modern minded Kikuyu, flashing cell phones and Ray-Bans, happily journey to Mount Kenya and pray to Ngai, the supreme God of the animists - despite often being members of one of the numerous Christian sects, such as the Pentecostals or the gospel churches. In this way, Stenger adds, Christianity and the pagan belief in nature deities and demons mutually impact one another. The existence of a god of creation in nearly all pre-Christian African religions encourages this process.

This cross-fertilization is not as strange as it may sound, even to Christians in the West. Something quite similar occurred there centuries ago, “when pagan Germanic customs mingled with Christian rites,” says Stenger. “Even Christmas - that most traditional of Christian celebrations - has ancient Germanic roots.”

In Benin City, Nigeria’s “human trafficking hub,” where the women from the region’s slums begin their journeys to Europe’s red-light districts, the path to the gods of nature runs through a backyard reeking of urine. The voodoo priest Chief John Odeh receives his flock in a white gown. His upholstered throne is trimmed with red satin. Beside him hang drums made of cowhide and the sword-like insignia of his position, known as Eben and Ada.

“Christianity has destroyed our culture. The people have lost faith in our ancient gods and values,” the animist priest laments. Ape skulls, amulets and shells are laid out on the concrete floor of the adjacent garage. Figures of Ogun, the god of iron, Orunmila, the god of wisdom, and Olokun, the god of waters, adorn this unusual shrine. Osalobua, the supreme God, punishes theft swiftly and without mercy, says Odeh. And the dead hear every lie told by the living. “The pastors go to church in the morning and preach Christianity,” says the voodoo priest. “And in the evening they come to me and speak with their forefathers.”

AP

A woman carrying a bowl of blood in Ouidah, Benin following an animal sacrifice.

Does He approve?

Odeh shrugs his shoulders. “Christianity cannot compete with our ancestors. Your God is impotent against Shango, the god of thunder and lightning. That’s why the Christian pastors in Nigeria all die so young.” The voodoo priest is holding some kola nuts in his hand. He scatters them on the dusty floor and prophesies the future. His predictions are as accurate as horoscopes in the yellow press.

Odeh celebrates his masses in Otofure, a village some 20 minutes from Benin City. This, inside the tropical jungle, is the realm of Owa Oba Asoon, a weathered wooden figurine with a greenish sheen that embodies the King of the Night. The priest blows into his cow horn, the altar boys beat their drums. The ground is littered with animal skulls, fetishes - and empty liquor bottles.

As the voodoo mass begins, Odeh flourishes a chicken over his head, mumbles unintelligible incantations and pours liquor over the skulls. Then he takes a knife and cuts the bird’s throat. Blood fountains in every direction, splattering onto the wooden fetishes - crudely carved figures with huge penises. More liquor is dispensed, another invocation mumbled, bringing the juju ceremony to its conclusion. Tribute has been paid and the King of the Night appeased.

Satisfied, Odeh pockets the $100 this service nets and hustles to his car. The faithful are waiting in the city. Nervously he glances at his watch, which is made of gold. His car too suggests an affluent lifestyle. “Oh well,” he says disingenuously, “that’s how things are nowadays. Nothing’s free in life except death.”

Article…

Print

Feedback

Related SPIEGEL ONLINE links

What People Believe in: Atlas of the World’s Great Religions(01/18/2007)

Monasteries in Germany: Looking for Monks and Nuns in the New Millennium (01/25/2007)

What’s the Real Difference? Islam and the West (01/23/2007)

Related Topics

Africa

Religion

© SPIEGEL ONLINE 2007

All Rights Reserved

Reproduction only allowed with permission

TOP

Die Homepage wurde aktualisiert.

Jetzt aufrufen.

Hinweis nicht mehr anzeigen.

89 notes

·

View notes

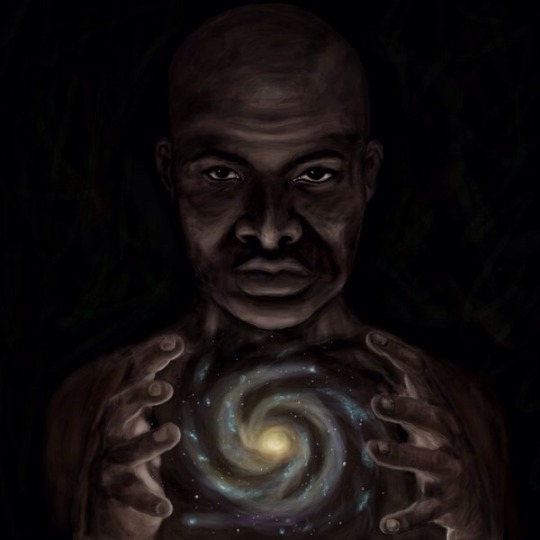

Photo

My maternal spirituality

Odinani(Igbo spirituality)

Igbo Spirituality 101

by

Onyii Anyiwo

The spiritual system of Ndi Igbo (the Igbo people) is one of the oldest on Earth. The roots of Igbo spirituality is the same as the roots of every other African one; that is, in Africa. Igbo spirituality predates Islam, Christianity, Judaism and every other -ism that one can think of. If there are any similarities between the traditional practices of the Igbo and those of other religions, it is because they were borrowed from our ancestors, and not the other way around.

The ancient spirituality of the Ndi Igbo, like most other traditional African spiritual systems, has been misunderstood and demonized unjustly. Evangelical churches, with the help of Nollywood movies, have helped to paint a negative picture of traditional Igbo spirituality that dates back to the arrival of the Europeans in Alaigbo (Igboland). It is quite unfortunate that most of the people who condemn Igbo spirituality do not know much about it, and base their most of their information from the lies of the very same people who wanted to destroy it and everything about our culture. While all the misconceptions about the traditional practices cannot be corrected in one article, this introduction to Igbo Spirituality will help clear a few things up.

The basis of Igbo Spirituality is the concept of “Chi.” Similar to the “Ori” of the Yoruba, and the “Ka” of Ancient Egyptians, Chi was the fundamental force of creation. Everyone and everything has a Chi. Ndi Igbo, like other Africans, worshiped one Creator, who is known by many names: Obasi Dielu (The Supreme God), Chi di ebere (God the merciful), Odenigwe (The Ruler of Heavens), etc. The two most popular names for Supreme Being used in Alaigbo were Chukwu and Chineke. The dominant name, Chukwu, which is a combination of the Igbo words “Chi” and “Ukwu”, literally means “The Big Chi”, and shows that Igbos believed that the Supreme Being was omnipresent and all-pervading. Chineke, which most people translate as “God the Creator” actually has a deeper meaning. Chi is the masculine aspect of God and Eke is the feminine aspect. Ndi Igbo knew that it took male and female to create life, so the Creator of everything would have to encompass both parts.

Because Ndi Igbo believed that everything in it had a chi, they also gave names to the Chi found in nature (the Alusi). The Alusi of the sky was known as Igwe. The Alusi of the yams (the most important crop of Ndi Igbo) was called Ahiajoku. The Alusi of the Sun was called Anyanwu. The most important of the forces of Nature was Ani, which was the feminine force that presided over the Earth. The Alusi were not limited to natural forces; metaphysical and supernatural forces and principles also had their own names and attributes. Ikenga was the Alusi of strength and Agwu was the Alusi of wisdom and healing. Each Alusi had its invididual personality and function, but they all were still parts of Chukwu.

The Ndiichie (esteemed ancestor spirits) also held a high place in traditional Igbo society. Elders have always been revered in Igbo society, and even more so after they passed onto Be Mmuo (the land of the spirits). The Nddichie would often be consulted to offer advice to their descendants and appeal to the Alusi on their behalf. Ndi Igbo have never worshiped their ancestors, only venerated them, which is no different then what Catholics do to their saints or what every country does to its national heroes. Respect and honor for the Nddichie was shown in one way by pouring of libations while chanting incantations. Ndi Igbo believed in the concept of reincarnation, and felt that the Nddiichie often reincarnated back on Earth. In fact, all Mmadu (human beings) were believed to reincarnate seven or eight times, and that depending on your karma, one either ascends or descends into another spiritual plane.

The personal relationship between God and Man in Igbo spirituality is as close as it can get. Ndi Igbo did not believe that they were separate from their Creator, and felt that the Chi that resided within them kept them connected. Igbo felt that their Chi was unique and personal and served as a guide and protector to them. A person’s destiny was also guided by their Chi. Those with a strong Chi would have prosperity, good health and good fortune, while those with a weak Chi would be prone to sickness, poverty and bad luck.

Even though the Igbo are largely Christian now, their traditional spiritual beliefs still live on. Along with these beliefs, a fundamental part of Igbo philosophy was “Biri Ka’m Biri” (live and let live). Ndi Igbo did not believe in fighting wars over religion. In their view, everybody should be able to worship God as they see fit. If there is any lesson from Igbo spirituality that we must not forget, it is this one.

2K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Lion-headed Stand, 1150, Cleveland Museum of Art: Islamic Art

The four sections of this stand each terminate in a lion’s head and the supporting legs end with a paw. The angular modeling of the lion’s head contrasts with the delicate silver inlaid decoration.

Size: Overall: 14 cm (5 ½ in.)

Medium: cast brass inlaid with silver

https://clevelandart.org/art/1931.453

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

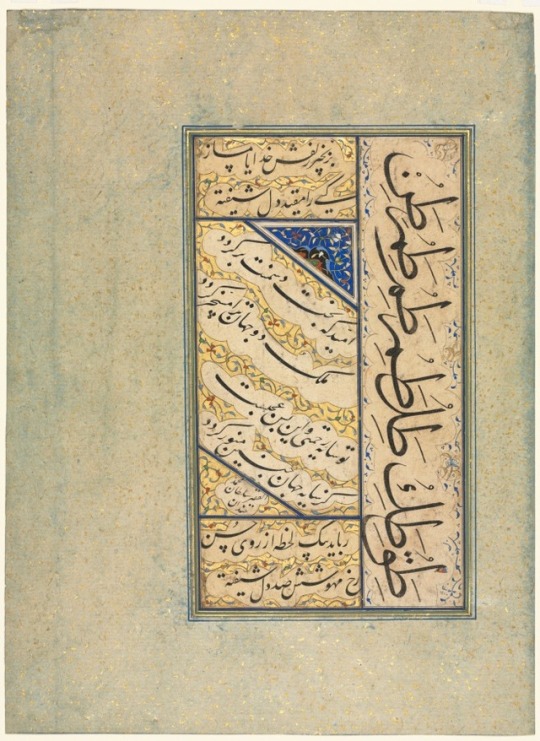

Persian Quatrains (Rubayi) and Calligraphic Exercises (recto); Persian Verse (khamriyya) (verso), c. 1509-59, Cleveland Museum of Art: Islamic Art

This page contains two quatrains—poems made up of four lines. The diagonally written text in the center of the page is a poem addressed to a ruler, expressing hope for his success and the downfall of his enemies. The second poem is split between the horizontal panels at the top and bottom of the page. This quatrain praises the beauty of the writer’s beloved, saying that “her moonlike face can steal away a hundred besotted hearts.” At the right are calligraphic exercises displaying letters of the alphabet and the virtuoso skill of the calligrapher Sultan Muhammad Khandan, who signed the page in the triangle at the lower left of the inner text block.

Medium: ink, gold, and opaque watercolor on paper

https://clevelandart.org/art/1983.1115

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

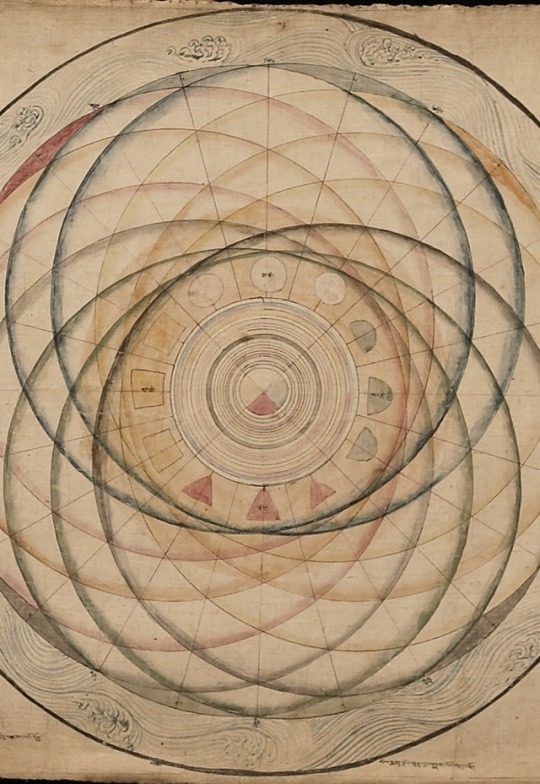

COSMOLOGICAL SCROLL

16TH CENTURY

Tibet

Medium

Pigments on cloth

Dimensions

19 x 79 in.

Credit

Rubin Museum of Art

585 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Leaf from Album of Actor Portraits, Shorakusai, c. 1790-1810, Cleveland Museum of Art: Japanese Art

Size: Painting only: 21.8 x 17.6 cm (8 9/16 x 6 15/16 in.); Each page: 28.1 x 21 cm (11 1/16 x 8 ¼ in.)

Medium: album of 25 leaves; ink and color on silk

https://clevelandart.org/art/1988.105.s

33 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Bando Hikosaburo III Holding a Hand Pupper, Katsukawa Shunsho, mid 1770s, Cleveland Museum of Art: Japanese Art

Size: Sheet: 33 x 15 cm (13 x 5 7/8 in.)

Medium: color woodblock print

https://clevelandart.org/art/1921.324

25 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Candelabrum Pair, Pierre Philippe Thomire, c. 1780-1785, Cleveland Museum of Art: European Painting and Sculpture

Size: Overall: 92.8 x 41 x 28 cm (36 9/16 x 16 1/8 x 11 in.); Part 1: 45.8 cm (18 1/16 in.)

Medium: bronze, gilt bronze, gray marble

https://clevelandart.org/art/1942.58

154 notes

·

View notes

Photo

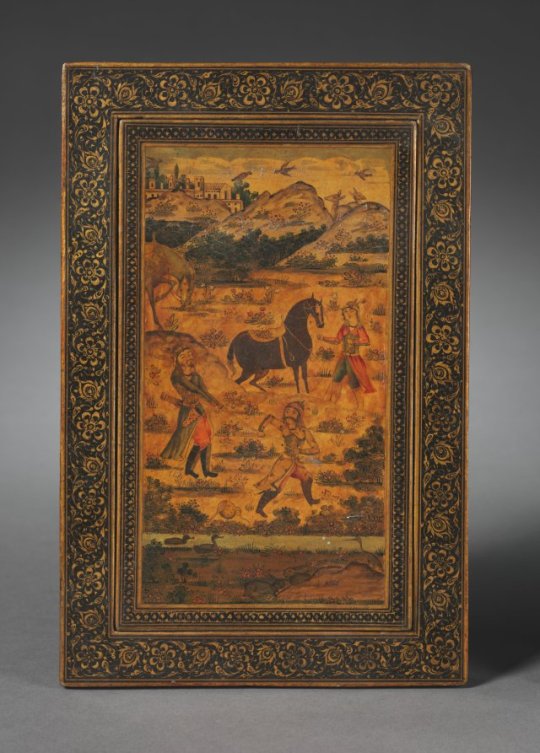

Mirror Case, 1800, Cleveland Museum of Art: Islamic Art

Love and war are the themes of the paintings on the inside and outside of this mirror case. The inside surface of the lid is painted with a royal couple seated, touching each other, within a walled garden. In front of them a female dancer performs and another pours a cup of wine. Military scenes are painted on the exterior sides; on the underside of the case enemies flee, heads roll, and a corpse lies before the victorious king and his armies.

Size: Overall: 24.4 x 16 cm (9 5/8 x 6 5/16 in.)

Medium: lacquer

https://clevelandart.org/art/1932.13

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Case (étui) with an amorous inscription, Metropolitan Museum of Art: Medieval Art

Rogers Fund, 1950 Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY

Medium: Leather (Cuir bouilli), wood core, red cord

http://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/468350

238 notes

·

View notes

Photo

GANGA DEVI ॐ

✨ OM NAMAH SHIVAYA

Shri Vishnu said:

“If one utters “Ganga”, “Ganga”, though one is a hundred yojanas away from the Ganges, one will be freed of all sins and go to Vishnuloka.”

64 notes

·

View notes