Text

Chronicles of the Three Kingdoms, Achilles Fang

The Chronicles of the Three Kingdoms were lost when Scholars of Shenzhou died. It was alive in the form of blogposts by Daolun, and I later compiled them into easy to read documents. However, after we both nuked our channels, they were lost. Since I am reopening a Tumblr account, I might as well put them here again for those interested in reading this book.

What is it about?

It's just the translation of the ZZTJ narrating the events from Cao Pi's usurpation to the fall of Liu Bei's Han. These years were not covered in Rafe de Crespigny's To Establish Peace.

As for those unaware of what the ZZTJ is, it's a history book written by Sima Guang during the Song dynasty that chronicles the events that happened in China year by year. The events cover pretty much all of China's history up until the Song, so it's a very thorough and comprehensive look at it. The relevant years have been translated by Rafe and Achilles Fang. Sima Guang usually just takes the sources and copies them outright, making sense of them and placing them in chronological order. Most passages reference events that are written in the Records of the Three Kingdoms and its respective biographies, but he includes other sources as well. Sima Guang doesn't cite them, but the translators do, so it's easier to know where info is coming from. Without further ado, here they are.

Volume 1: 220 - 249

Volume 2: 250 - 264

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Zhaolie Archives

Hello, this is Zhaolie. I used to write articles on Three Kingdoms history, especially on the Third Han and their figures. Due to personal struggles, I ended up getting depressed and deleted all of my work. However, I realize that was probably selfish, so I am reopening the blog to get those articles again and do a little tweaking, like combining the Zhuge Liang and Jiang Wei into one article for each person. I also reposted the link containing the translated SGZ of the Three Kingdoms period, which many of you may find useful.

As for everything else, I will not be using this account. I am done with the Three Kingdoms community and have been for quite a while, even if I occasionally check out some posts. I will not be posting any new content from here on out. If my passion for the Three Kingdoms rekindles, things may change, but since that could take years, do not count on it. I hope you can find this material useful nonetheless.

Zhaolie the Benevolent

0 notes

Text

A look at Jiang Wei parts 1 and 2

Jiang Wei is not an obscure figure. Everyone knows who he is. He’s certainly one of the most recognizable characters. However, if you ask others, they can’t really tell you a lot about Jiang Wei. I was in that camp too. I knew who he was and more or less what he did, but since he’s from the later parts of the Three Kingdoms period I never really dug deep into the man. This isn’t helped by the romance, that heavily simplifies events after the death of Zhuge Liang and becomes a lot duller as a result. So, today I’ll be talking about his honestly quite extensive career, his virtues and his flaws.

The early years

Jiang Wei, styled Boyue, was born around the year 201 in Ji county, Tianshui commandery. He was the son of Jiang Jiong, a minor official of Tianshui who held the rank of meritorious officer, a position subordinate to the commandery administrators. At some point during Jiang Wei’s youth, the Rong and Qiang tribes rose up and Jiang Jiong died fighting them [1]. There is no concrete date on Jiang Wei’s biography, and searching a bit some sites mention the year 214. That’s when Xiahou Yuan is noted to have pacified the Qiang west of mount Long, but I couldn’t find anything more concrete. Since then, Jiang Wei would live with his mother, holding the position of cadet and acting as a military adjutant to the administrator of Tianshui [2].

From an early age Jiang Wei displayed charisma and leadership, assembling a small retinue of men who were trained to die for him [3]. This dare to die corps was obviously not something he was allowed to have with such a low status, but it was his foray into training men and preparing them to fight. He also liked studying and was fond of confucian scholar Zheng Xuan’s texts [4].

With the death of Cao Pi in 226, Cao Rui succeeded him as sovereign of Wei. Since Cao Rui had only recently occupied the throne, Chancellor Zhuge Liang of the Han dynasty launched in 228 the first of his northern campaigns. With the newly ascended sovereign in the north occupied in state affairs, and after several years of relative quiet in the southwestern frontier, the invasion from the Han troops took Wei by surprise [5].

Zhuge Liang’s plan was to send a decoy army under general Zhao Yun to Mei while the main army marched to the Longyou area to take Yong and Liang, then from there take the ancient capital of Chang’an.

With the coming of the invading army, the administrator of Tianshui Ma Zun went on an inspection. As part of his staff, Jiang Wei accompanied him. It happened that the Han’s invading army caused several border commanderies to revolt, whcih included Jiang Wei’s native Tianshui. There seems to be different accounts of what happened. Jiang Wei’s own biography states that Ma Zun was suspicious of his staff officers and secretly left them, marching east to Shanggui. Jiang Wei, trying to reunite with the administrator, was not let inside Shanggui and he was rejected at Ji county as well. As a result, he defected to the Han.

An alternate account offered by Weilve is a bit more detailed. Jiang Wei did follow Ma Zun on his way to the east and urged him to go back to Tianshui. Ma Zun instead told him it’s better to scatter in face of the enemy, so Jiang Wei returned to his native Ji county. Once back home, the rebelling officers forced Jiang Wei to meet Zhuge Liang, and with him retreated after Ma Su’s defeat at Jieting, when the Chancellor led the people of those counties to Han. Since Jiang Wei had been forced to defect, his mother was not punished as a result.

There is no way to know which of these versions is correct, so I present both.

Regardless, Jiang Wei was a man of Han from then on, and it appears the Chancellor Zhuge Liang was quite impressed by him. On a letter to Jiang Wan and Zhang Yi, he wrote this about the new recruit [6]:

“姜伯约忠勤时事,思虑精密,考其所有,永南、季常诸人不如也。其人,凉州上士也。”又曰:“须先教中虎步兵五六千人。姜伯约甚敏于军事,旣有胆义,深解兵意。此人心存汉室,而才兼于人,毕教军事,当遣诣宫,觐见主上。”

Jiang Boyue is loyal and hard working on daily affairs, precise in though, meticulously examining his conduct. Yongnan (Li Shao) and Jichang (Ma Liang) can’t compare to him. He is an officer of superior qualities of Liang province.

He also added: He must first command the five or six thousand troops of the center tiger infantry. Jiang Boyue is adept in military matters, as well as possessing valor and righteousness. He deeply understands military principles. His heart is with the house of Han and his talent doubles that of ordinary men. I will give him authority on military affairs and have him go to palace to see His Majesty.

He also enfeoffed Jiang Wei as a village marquis and had him work as a staff officer under the General in chief. It appears that Jiang Wei did not disappoint the Chancellor, for he obtained sveral promotions during Zhuge Liang’s regency, reaching the rank of General who Campaigns West [7].

During the fifth northern campaign in 234, Zhuge Liang and Sima Yi faced each other at Wuzhang plains. Given the tactical prowess of the Chancellor, Sima Yi received an order from Cao Rui to stay in camp, for Sima Yi was frequently defeated whenever he went up against Zhuge Liang in open battle.

Despite his provocations, Zhuge Liang failed to make Sima Yi engage him in open battle and he died of illness. Before passing, however, he gave the order to retreat.

Rumors of the death of the Chancellor quickly spread, and Sima Yi was eager to advance in pursuit. The Han Jin chunqiu by Xi Zuochi mention that during this time Jiang Wei, then in Yang Yi’s camp, raised the flags and beat the drums as if he was going to attack. Sima Yi, thinking this was all a ruse by Zhuge Liang to lure him out, retreated [8]. When the army was on the way to Hanzhong, the Chancellor’s death was confirmed and made public.

Service under Jiang Wan

Back in Chengdu, Jiang Wei’s merits were recognized and he was given another promotion, this time as General of the Right and General who Upholds the Han. He was once again enfeoffed [9].

In the Romance of the Three Kingdoms, Jiang Wei becomes Zhuge Liang’s successor, but in history nobody really was Zhuge Liang’s immediate successor to the position of Chancellor. The Emperor had left the position vacant after Zhuge Liang’s death, and nobody else in the remaining history of the Han held that position again. Jiang Wan however was considered to be Zhuge Liang’s successor, and as inspector of Yi province [10], he was in charge of supervising state affairs.

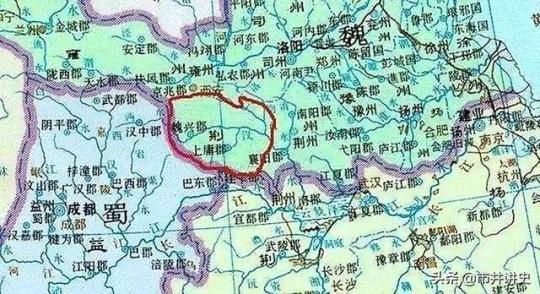

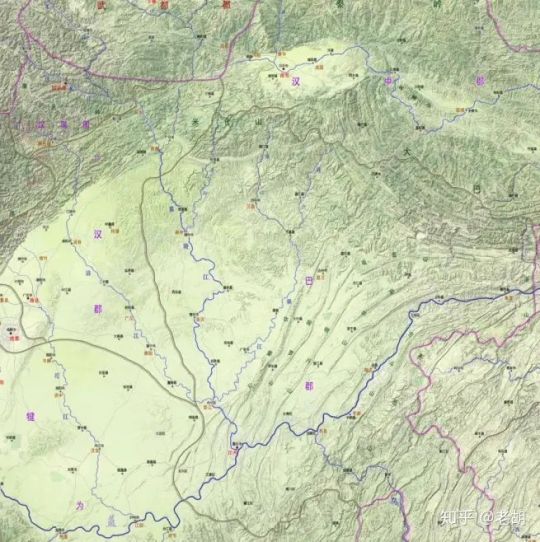

Jiang Wan’s plan was originally to advance East. https://i1.kknews.cc/SIG=362816l/ctp-vzntr/689os56o0o0o47239s75n9nqoo0r821o.jpg

Even though Han military activity slowed down during this era, the General in chief still had some plans to launch an expedition against Wei. His intention was to march East and invade Shangyong through the Han and Mian rivers, as Zhuge Liang’s northern campaigns didn’t find success. For this reason, Jiang Wan ordered a large number of ships to be built [11].

Unfortunately this plan was believed to be too risky. The difficult terrain makes the path to invade easy but retreat hard, so if the army failed to take the military objectives it could risk getting trapped and annihilated [12].

After some persuaion, Jiang Wan would modify this plan, intending to send Jiang Wei north to take the region West of the Yellow River, while he himself would station close to the Fu river. This location is important, as it was well connected by water and land, and would provide with Jiang Wei with support by reacting to military movements in the northeastern parts of the frontier [13], perhaps involving a surprise invasion to Shangyong.

This shows Jiang Wan had confidence in Jiang Wei, as he also suggested he be named inspector of Liang province. Moreover, Jiang Wan had used Jiang Wei on several incursions in the north and apparently performed well, given Jiang Wan’s eagerness to entrust more responsibility to him [14]. These invasions were probably just harassing campaigns to destabilize the west, as Guo Huai put Jiang Wei to flee without a battle [15], never meant to be a committed invasion of the north. These incursions, despite being small in scale, gave Jiang Wei insight into the Qiang and the northern frontier [16]. It makes sense Jiang Wan would choose him for a concentrated effort in the region.

This incursions likely ended in 242, when Jiang Wei camped by the Fu river, the same location that was central to Jiang Wan’s plan. In preparation for his invasion of the north, he had Jiang Wei formalized as Grand General who Subdues the West and inspector of Liang province in 243 [17].

This plan was not to be executed, however, as in 244 Jiang Wan would leave his post of General in Chief to Fei Yi, likely because of illness. Jiang Wan finally died at the beginning of the year 246.

Service under Fei Yi

Under new leadership, Jiang Wei’s campaigns didn’t really change in nature, getting involved in small campaigns and suppressing rebellions [18]. One such campaigns was the one of 247, when several Qiang tribes rose up in Nan’an and Jincheng, switching their allegiance to the Han [19]. Jiang Wei invaded from Longxi and defeated Guo Huai and Xiahou Ba [20]. He tried pressing the attack to Didao, but retreated back home, bringing with him many of the defecting tribes to Han.

In 248 Jiang Wei once more took advantage of the unrest of the Qiang and invaded to gather the defeated Qiang rebels and unite with the fleeing Zhiwudai. Marching west, he ordered Liao Hua to build a fortification at Chengzhong. In order to avoid Jiang Wei from uniting with Zhiwudai, Guo Huai attacked Liao Hua, forcing Jiang Wei to go back to rescue him [21]. Unable to rendezvous with Zhiwudai, Jiang Wei and Liao Hua retreated.

Later the following year, Jiang Wei once again was ordered to invade. Similarly to his previous campaigns, he cooperated with the Qiang to put pressure on the northern frontier and built fortifications in Chu. Since Chu was far from home, the supply lines were vulnerable. Wishing to isolate Jiang Wei and capture him, Guo Huai and Chen Tai surrounded the fortress at Chu and attempted to cut off Jiang Wei’s retreat at Mount Niutou. Jiang Wei outmaneuvered Guo Huai and retreated, but Gou An, the officer guarding Chu, surrendered [22].

With the Qiang suppressed, Deng Ai suggested leaving some military presence in the region in anticipation of Jiang Wei coming back and camped north of Bai river. Jiang Wei then decided to send Liao Hua with a decoy force to threaten Deng Ai while he himself would lead the men across the river to Taocheng, a position that, if occupied, would outflank Deng Ai’s position and would rout his men. Deng Ai, however, saw through this feint and garrisoned Taocheng. Jiang Wei retreated seeing the place had already been occupied [23].

Earlier Cao Shuang had been exterminated with his entire family by order of Sima Yi. Fearing for his life, Xiahou Ba defected to the Han and became acquainted with Jiang Wei. It is through Xiahou Ba that Jiang Wei allegedly first heard of Zhong Hui, as Xiahou Ba believed him to be a force to be reckoned with [24]. Given the prophetic nature of this passage and Jiang Wei’s later history with Zhong Hui, I suspect this is just a cliché.

During this period, on the domestic side, we start observing the first signs of decline. Dong Yun died in 246, and Fei Yi appointed Chen Zhi to succeed him as inside attendant. Dong Yun was quite strict and was cautious of the eunuch Huang Hao, warning the Emperor that such a man should not hold a high position. Chen Zhi, however, was very fond of Huang Hao and promoted him after Dong Yun’s death. Huang Hao’s influence at court would only grow as he was given free reign to manipulate the Emperor and staff the different positions with his yes men [25]. Considering the fate that Huang Hao suffered [26], I doubt those appointments were even coincidentally good. As a result, the domestic situation of Han would decline after Fei Yi died and Jiang Wei failed to leverage his influence against Huang Hao.

As for the military side of things, the campaigns under Fei Yi had a much more limited scope, focusing on exploiting tensions between Wei and the Qiang and capturing population to work the land rather than an effort to launch a grand campaign. Jiang Wei often had more ambitious plans that he brought to his superior, but Fei Yi rejected them and never had him lead more than 10.000 men at any given time [27]. As a result, Jiang Wei couldn’t afford to press the attack or contest well defended positions and successes were pretty minor. During his incursion to Xiping on 250, Jiang Wei captured Guo Xun, an officer of Wei. Guo Xun assassinated General in Chief Fei Yi in 253. It is ironic that the minor success of capturing an enemy officer in the smaller scope invasions that Fei Yi advocated for would lead directly to his death.

The death of Fei Yi meant that it was Jiang Wei’s turn to take the mantle as General in Chief and realize his northern campaigns. While he would be given the position a few years after the death of Fei Yi, he nonetheless received more military authority right after the previous General in Chief’s passing [28]. Jiang Wei’s role as General in Chief would be paralell to the further influence of Huang Hao, who would damage the administration and contribute to the fall of the State.

Interestingly enough, this decline ran paralell to that of each of the three kingdoms: Wei would suffer from armed rebellions of various generals as they cling to the withering house of Cao or rally behind the emerging Sima clan, and in Wu, Zhuge Ke would fall and Sun Jun would seize absolute power and tyrannize the people, leading to the rise and fall of emperors in the south.

The following years would be tumultuous, as Jiang Wei’s career intensifies.

(Part 2 begins here and the references start from number 1 again)

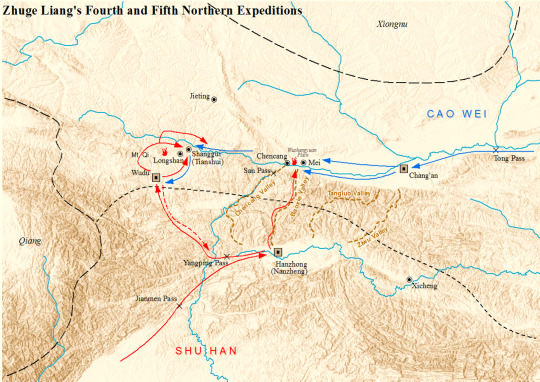

General in Chief of the Han: Taoxi and Shanggui

253 was an eventful year. Sima Yi had died a few years back and his son Sima Shi was in control of the army. Previously, Wei invaded Wu and the invading army was defeated at Dongxing by Zhuge Ke. Wishing to seize the momentum, Zhuge Ke launched a counter invasion and besieged the new city of Hefei on this year [1].

In coordination with Wu’s advances, Jiang Wei also led several tens of thousands of men to besiege Nan’an [2]. Since he thought Wei would be occupied dealing with Wu’s counterattack, Jiang Wei didn’t bring many provisions, hoping to quickly take Liang and take the supplies from there [3]. When Chen Tai and Guo Huai quickly advanced to relieve the siege, Jiang Wei retreated. Zhuge Ke was defeated as well, so in the end no gains were made by either ally.

Jiang Wei’s campaigns started to intensify to the point where he would lead a campaign pretty much every year for a while. While the ultimate goal of taken Liang province was never realized, Jiang Wei found some form of success in some of these invasions. Jiang Wei’s campaign of 254 is one of these.

That year he set forth and marched onto Didao. The reason for this is that the county chief of Didao, Li Jian, wrote a letter asking to defect and invited the army. Despite many people’s doubts about Li Jian’s honesty, Zhang Ni [4] and Jiang Wei believed it to be true. Zhang Ni was sent to welcome Li Jian’s surrender [5], but Wei’s general Xu Zhi engaged the troops in battle to stop them. Jiang Wei and Xu Zhi clashed at Xiangwu county, with Zhang Ni’s contingent led by him personally [6]. Despite the illness he was suffering at the time that prevented him from even getting up on his own, he still managed to kill many of the enemy’s troops [7].

Despite the loss of his general, Jiang Wei still greatly defeated Xu Zhi. The enemies killed were numerous [8], including Xu Zhi himself, who either died in battle or was beheaded after his capture.

Having overcome his foe, Jiang Wei followed up his victory by advancing towards Hejian (possibly actually named Heguan according to Hu Sanxing)[9], Didao and Lintao counties, taking the people with him and marching back home [10]. Despite Zhang Ni’s death, this incursion was pretty successful. While some may bring up Jiang Wei’s inability to take Liang, this campaign began because Li Jian of Didao county wanted to defect. Having escorted him and the local population safely to Han is already a benefit to the state and a positive thing. That Liang province couldn’t be taken was because Li Jian was just a county chief [11] and his defection couldn’t impact the balance of power in the province that heavily in Han’s favor. Jiang Wei probably realized this and limited his military goals. In the end he destroyed Xu Zhi and got more population to work the fields, certainly a success given the circumstances.

In 255, Sima Shi died during the suppression of Guanqiu Jian and Wen Qin’s rebellion. That same year, Jiang Wei with Xiahou Ba once again marched north to Didao, despite Zhang Yi firmly opposing this decision [12]. The inspector of Wei’s Yong province, Wang Jing, was put in charge of the defense at Didao. Chen Tai told him to wait for reinforcements and hold out Han’s invading army. However, Wang Jing engaged Jiang Wei directly. Chen Tai imagined something must have been amiss and the situation had changed for him to sally out [13].

Both armies clashed at Taoxi, or west of the Tao River. The details of this battle are scant, but the result is clear: it was a resounding victory for Han and one of Wei’s biggest losses in its history. Jiang Wei utterly crushed Wang Jing and inflicted casualties that are described in the tens of thousands of men [14]. This number is nothing to scoff at, and I can’t stress enough how big it is. For comparison, Cao Xiu’s troops at Shiting amounted to ten thousand [15], and a similar number is given in regards to Wei’s casualties at Dongxing [16].

After the battle, Zhang Yi suggested to retreat, be content with the achievement and retreat back to Han in order to preserve morale [17]. Jiang Wei, once again, disagreed with Zhang Yi and pressed the attack to Didao, where Wang Jing’s remaining army was holed up.

Chen Tai remarked the strategic situation at hand: Jiang Wei had overextended himself and pressing the attack on Didao means he won’t commit to taking a supply base on Lueyang or to rally the Qiang against Wei like in previous campaigns [18]. However, the reality on his side was that Wang Jing had suffered very heavy casualties and his morale was low, and Chen Tai’s own army wasn’t in the best fighting condition either [19]. He thus decided to use guile in order to make Jiang Wei retreat.

Taking the high ground, Chen Tai made a display of force, loudly proclaiming his coming and raising numerous flags to inspire the allies guarding Didao. Jiang Wei was surprised at the speed by which reinforcements had arrived, and after attacking Chen Tai unsuccessfully, he led his men in retreat. Wang Jing was grateful for the reinforcements, as he didn’t feel like he could have held out for much longer with the supplies he had [20].

Jiang Wei has attracted criticism in the three kingdoms community because of the way he had conducted this campaign, citing Zhang Yi’s remarks and Chen Tai’s evaluation of the situation. I have several arguments in favor of Jiang Wei’s siege of Didao.

Wang Jing’s defeat at Taoxi was devastating. Such a high number of casualties was pretty rare and only a handful of battles during this entire period had comparable numbers. It was an impressive feat that not even Zhuge Liang could pull off. This naturally weakened Wang Jing’s morale significantly.

Just because Jiang Wei retreated doesn’t mean Zhang Yi was right and his approach was perfect. Let’s not forget he was against the campaign from the very beginning, being unwilling to continue even after finding success. While it is true that if Jiang Wei had retreated the army could preserve its morale, this shows a lack of ambition that I personally find frustrating.

Following up on the previous point, one flaw of Zhuge Liang’s was that, despite his victories on the battlefield, he often did not capitalize on them. Jiang Wei had already been witness to that, as well as being constricted by Fei Yi’s more passive stance. Jiang Wei understood that to simply retreat after such a crushing defeat of the enemy would be to waste all the momentum gained with successful tactics, rendering the victory ultimately empty. Why would Jiang Wei retreat after humiliating Wei like this? Is that how Han was supposed to win the war? By retreating at the height of success? This was a war of unification, not a videogame. The objective is not to get a high score, it is to unify the land. Not capitalizing in victories is a defeatist attitude and would only lead to destruction. Imagine if Liu Bei and Zhou Yu decided to go home after Red Cliffs. Would we be talking about three different kingdoms here then?

Chen Tai naturally understood the risks of Jiang Wei taking Lueyang or riling up the Qiang. However, I don’t think this assessment discredits Jiang Wei. What Chen Tai was talking about was one way to approach the attack, and a perfectly valid one. However, Jiang Wei’s rationale is perfectly sound. Aiming straight for Didao was a somewhat risky move given the distance from Han and the lightly armored troops he was leading, but it still has its merits. Wang Jing himself had mentioned a lack of supplies, so it is quite likely that Jiang Wei saw the opportunity to take Didao quickly and use it as a base to press the attack on Wei. What I’m about to say is admittedly conjecture on my end, but Wang Jing perhaps saw his supplies were not enough to withstand a protracted siege and decided to sally out, defeat Jiang Wei and at least buy some time by forcing him on the degensive. Regardless of Wang Jing’s motives, the reality is that his supply situation was dire, and if Jiang Wei had committed more to the siege, taking Didao was absolutely not out of the question.

It is unlikely that Jiang Wei suffered heavy casualties to Chen Tai, as his adjutants noted his army was not in the best fighting condition [21]. More than likely, Jiang Wei saw he could not dislodge Chen Tai of advantageous terrain and chose to retreat lest he threatened his rear and disrupted his supply lines. He also was suspicious of a ruse by Wei, as the speed at which Chen Tai arrived had caught him off guard. Because of this, Jiang Wei didn’t commit his men to a full attack and retreated shortly after. The fact that Chen Tai had enough prestige to make Jiang Wei suspect a ruse, if anything, speaks more of Chen Tai’s talent than Jiang Wei’s incompetence.

While the campaign was ultimately unsuccessful, Taoxi stands as Jiang Wei’s greatest victory and one of Wei’s greatest defeats. For this achievement, Jiang Wei was named General in Chief, just as Jiang Wan and Fei Yi had held before him, and it was earned.

The events of 256 also prove that Jiang Wei’s retreat was not that damaging to the Han in terms of morale. While the costs are in lost opportunities, Deng Ai still thought Jiang Wei’s army was a worthy foe and had not yet exhausted his strength. In fact, Deng Ai remarked that the region was in dire straights after Jiang Wei’s last incursion, and that he would indeed follow up sooner or later [22].

Jiang Wei marched towards Mount Qi, but seen it tightly defended by Deng Ai, he changed his route to Nan’an. There, Deng Ai had occupied advantageous terrain and Jiang Wei was unable to contest it [23].

His next march was towards Shanggui, crossing the Wei river. He had arranged for General who subdues the west Hu Ji to rendezvous with his army there. For one reason or another, however, Hu Ji failed to show up. This left the Han troops without supplies [24].

This proved quite disastrous, in fact. Jiang Wei engaged Deng Ai at Duan Valley, where Deng Ai heavily defeated Jiang Wei’s invading army, putting an end to the campaign. A memorial congratulating and rewarding Deng Ai for his victory numbers Jiang Wei’s casualties in the thousands, and some minor officers were killed as well [25].

Despite Jiang Wei’s success that propelled him to General in Chief, his edge was blunted by Deng Ai at Duan valley, and while the number of casualties is not exact, they must have been considerable, for the people of Han complained about it and came to dislike Jiang Wei as a result. While Hu Ji is blamed in the sources for this defeat, it strikes me as odd that Jiang Wei would simply ignore that Hu Ji was not there. Jiang Wei clearly must have known his army was poorly supplied because of Hu Ji’s absence. Why then did he engage Deng Ai? This was too reckless.

Regardless, Jiang Wei agreed with my sentiment, as he blamed himself for this defeat and requested his own demotion, being named General of the Rear, but was still in charge of the army [26].

Next year, however, an opportunity presented itself. Wei’s Zhuge Dan had revolted in Huainan and requested help from Wu in order to oppose the Sima family. Jiang Wei decided to march north once again, knowing that the army would be occupied dealing with Zhuge Dan [27].

He marched towards Chancheng, an important supply depot in the area that was lightly defended. Knowing the importance of this location Sima Wang marched towards Chancheng and tightly defended it, with Deng Ai on his way. Despite Jiang Wei’s provocations, Deng Ai and Sima Wang refused to engage him in battle, learning the lessons of Taoxi [28].

The following year, Zhuge Dan was killed and Jiang Wei felt compelled to retreat. His status as General in Chief was restored [29].

Jiang Wei’s final northern campaign was carried out on the year 262. It was a rather unremarkable affair. Jiang Wei advance to Houhe and was defeated by Deng Ai, forcing him to retreat back to Tazhong. This campaign was met with opposition from the start [30], and the fruitless nature of it most certainly did not help his case.

In fact, such was the case that Huang Hao conspired to dismiss his from the post of General in Chief and place his close associate Yan Yu in power as Jiang Wei’s substitute. Jiang Wei was dissatisfied and urged the Emperor to execute him immediately. The Emperor however, refused, but nonetheless had Huang Hao apologize to him [31].

This open move against Huang Hao put Jiang Wei on the corsshairs. Not daring to go back to Chengdu lest he came to harm, Jiang Wei stationed at Tazhong [32] and never again marched north against his long time rivals.

Jiang Wei had been unsuccessful in his northern campagins. Concerned with supplies and advancing deep into enemy territory, it was often that his supply lines were threatened and sometimes he suffered heavy losses like at Shanggui. Despite this, it’s quite remarkable how Jiang Wei’s new defense strategy revolved precisely around reverting these roles. That is to say, developing a new strategy that in theory would make the enemy overextend themselves with the purpose of launching a vigorous counterattack, completely crushing the enemy and replicating the great victory at Taoxi.

For this purpose, he abandoned the several passes into Hanzhong and wished to garrison Hancheng and Luocheng [33]. If you remember my article on Zhuge Liang’s campaigns, these are the fortresses he built to meet Cao Zhen’s invasion, carefully placed to meet the marching enemy and easily defeat them after an arduous march across the Qinling [34].

By inviting the enemy in, he could fight Wei on his own terms, harrassing the weak spots in the enemy’s formation and straining their supply situation. By stalling an invading army and forcing them to exhaust their provisions, he would cause them to retreat through treacherous roads, an opportunity he would use to pursue the enemy and obliterate their army in one stroke [35].

This defense plan has been heavily criticized, and not undeservedly so as it ultimately didn’t work. I personally think it was a plan with plenty of merit, even if its execution was flawed. I will go more in depth later about how viable this plan was, but for now I will simply say that this approach would potentially be a lot more effective than the previous defensive arrangements. While the passes that protected Hanzhong were a formidable defense, they were used to simply repel enemy invasions that retreated after encountering impassable fortifications. They were used quite effectively by Wang Ping, for example, but Cao Shuang didn’t lose a significant number of men [36].

Because of this, even though Han was safe, Wei could return relatively unscathed. Jiang Wei’s approach is a lot more daring and fresh, with the potential to deal a very heavy blow to his former state and severely weakening them.

Unfortunately he was up against formidable foes.

The fall of the Han

Sima Zhao made note of the change in development in the western frontier. He had previously been offered the Nine Bestowments and the title of Duke, having rejected every time [37]. Now obviously it was him appointing himself to those titles so that he can reject them and make a display of loyalty and humility [38], but he truly did covet those honors and much more.

Wishing to justify his accession with a military conquest, he thought the defeat of the Han would propel his prestige enough to make his final moves towards emperorship. Not only was this a political decision, it was also strategic. With Han annexed, his troops could sail down the Changjiang, strike at Wu from water and land and unify the empire once and for all, this time under a new regime [39].

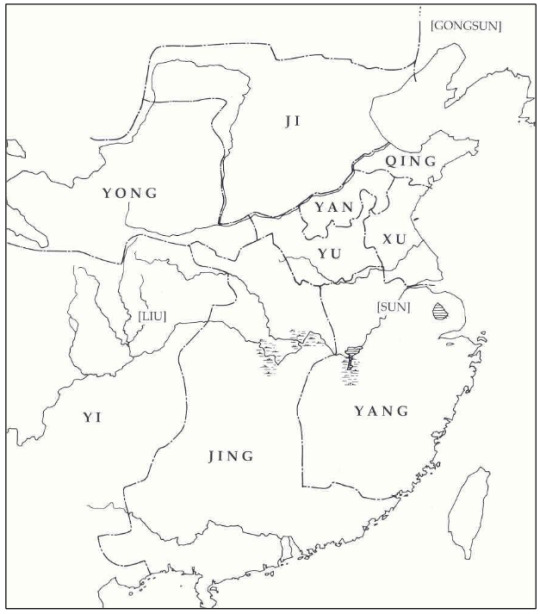

In order to do so, he planned with Zhong Hui a three pronged invasion of the Han. The three main commanders would be Deng Ai, Zhuge Xu and Zhong Hui, numbering approximately 160.000 troops (100.000 under Zhong Hui, 30.000 under Deng Ai and Zhuge Xu each) [40].

At the time, Jiang Wei was stationed at Tazhong with 50.000 men, west of Hanzhong, and requested more men to face the incoming invasion. Huang Hao thought Wei wasn’t really going to invade, hence Jiang Wei’s reinforcements did not arrive [41].

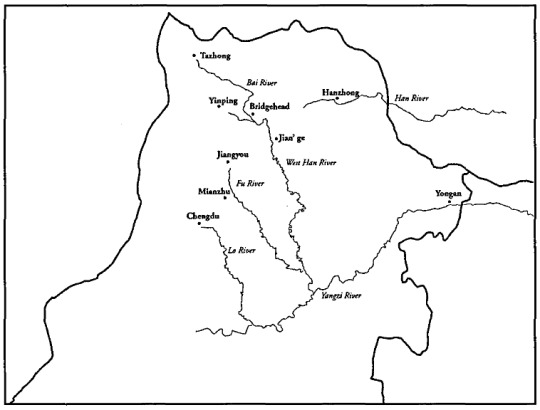

Even though the map is rather featureless, it pinpoints the main locations in this invasion. From: John W. Killigrew (2001) A case study of Chinese civil warfare: The Cao‐Wei conquest of Shu‐Han in AD 263, Civil Wars, 4:4, 95-1

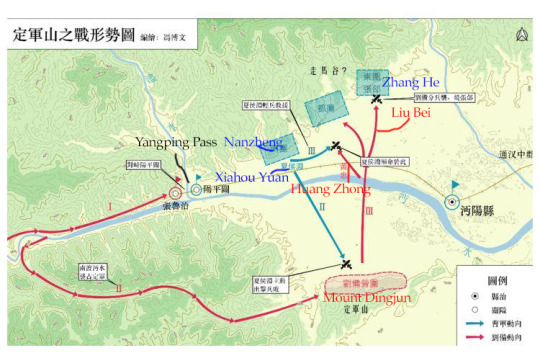

Sima Zhao’s plan was simple. Zhong Hui would advance from the northeast through Ye, Luo and Ziwu valleys into Hanzhong to take this strategic location, the gate to Shu. The main problem was the defensive stronghold of Jian’ge, the last line of defense before the Chengdu plain [42].

Since Jiang Wei was stationed in Tazhong, Zhong Hui’s army was to be assisted by Deng Ai and Zhuge Xu. Deng Ai would advance from Didao on the northwest to engage with Jiang Wei directly, and Zhuge Xu would advance from Mount Qi on the north towards the bridgehead of Yinping. This way, Deng Ai would hold down Jiang Wei and Zhuge Xu would cut off his escape route. With Jiang Wei pincered between two large forces, Zhong Hui could march through Jian’ge unopposed and strike Chengdu directly [43].

The invasion began in 263 and things had originally gone as planned. Zhong Hui entered Hanzhong, and as per Jiang Wei’s plans, the fortresses of Hancheng and Luocheng were tightly guarded. Only then did the Emperor authorize reinforcements, sending Liao Hua to aid Jiang Wei at Tazhong and Zhang Yi with Dong Jue to reinforce Yang’an pass [44].

On their front, Deng Ai and Zhuge Xu made their move. Jiang Wei was defeated in a minor engagement and decided to move to Hanzhong to reinforce those fighting Zhong Hui. It happened that Jiang Shu had defected and guided the invading army to attack Yang’an pass, taking it . With Hanzhong lost, Jiang Wei marched towards Yinping, but discovering Zhuge Xu was in the vicinity. With effective maneuvering, Jiang Wei feigned an attack north to outflank Zhuge Xu, and this, feeling threatened, chose to retreat [45].

In this moment, Jiang Wei turned and marched straight to Jian’ge, where he met up with Liao Hua and the others and was ready to defend the bastion with tooth and nail. With this maneuver, Jiang Wei had outmaneuvered Deng Ai and Zhuge Xu [46], and the speed in which he marched made Zhong Hui hit a roadblock at Jian’ge.

The original plan of Sima Zhao had failed, as Jiang Wei could not be restrained and marched onto Jian’ge, stopping the northern hordes in their tracks. However, the reality of the situation is that Hanzhong was taken, and given this success, Sima Zhao took the opportunity to finally accept the title of Duke of Jin [47].

The defense of Jian’ge was fierce. Jiang Wei’s impenetrable formation proved too much for Zhong Hui to overcome, and since the supply situation was dire, he seriously considered to retreat [48], just as Jiang Wei’ had envisioned in his defensive plan.

At this juncture, Deng Ai took an undefended Yinping and wanted to advance towards Jiangyou in a daring march to outflank Jian’ge and aim straight for Chengdu. Zhuge Xu thought this was not the original plan, and since he had failed to stop Jiang Wei, he joined up with Zhong Hui, who stripped him of his command [50].

Deng Ai decided to take matter into his own hands and adapt to the changing situation. The march into Jiangyou was incredibly arduous. The terrain was very hard to traverse through, and at some point Deng Ai had to roll himself in felt in order to advance [51]. Despite the difficulty that the terrain posed, Deng Ai still managed to reach Jiangyou, that surrendered immediately. The men of Han were caught completely off guard by Deng Ai’s daring march, as the route was considered so difficult that it was not thought the enemy would risk marching through it.

With this surprise attack, the court sent Zhuge Zhan, who marched to Fu. Undecided to take the defiles and defensive terrain [52], Zhuge Zhan was defeated and retreated to Mianzhu. Deng Ai engaged him in battle and was unsuccessful. Understanding that failure meant total annihilation [53], as there really was no viable way to escape, he pressed the attack and successfully defeated Zhuge Zhan, killing him in battle.

With Deng Ai in the proximity, the Emperor was offered an array of different advice, like fleeing to Wu or preparing a defense at Nanzhong. Qiao Zhou, one of the critics of Jiang Wei’s foreign policy, thought the best course of action was surrender [54]. The Emperor agreed and capitulated, ordering Jiang Wei to lay down his arms and yield. The Han dynasty had finally fallen.

The fall of the Han. Taken from: https://www.bilibili.com/read/cv1954392

Final attempt at restoration and death

Obeying the imperial command, Jiang Wei surrendered to Zhong Hui. Zhong Hui was deeply impressed with his rival, putting him above men like Zhuge Zhan, Zhuge Dan or Xiahou Xuan [55]. From then on, Jiang Wei and Zhong Hui became friends, though it wouldn’t be long before they died together.

However there was still work to be done. Deng Ai accepted the Emperor’s surrender and started giving out ranks and enfeoffments, some positions to serve under him directly [56]. Because Deng Ai had stepped out of his boundaries, Zhong Hui reported the matter to Sima Zhao. Zhong Hui himself had his own ambitions and rewrote the letters that Deng Ai sent to make his alleged words sound more arrogant than they actually were [57].

Since Zhuge Xu was stripped of his command, only Deng Ai remained to challenge his authority, so Zhong Hui was happy to send Wei Guan to arrest him. It so happened that Zhong Hui sent Wei Guan with only a handful of men so that Deng Ai felt confident enough to kill him, thus giving Zhong Hui a pretext to move against him and bringing him to justice [58].

Wei Guan sensed this and convinced Deng Ai’s officers that only he and his son Deng Zhong were to be punished, while his officers would still retain their rank and status [59].

With Deng Ai arrested, Zhong Hui stood as the de facto supreme commander of all Wei troops in Shu. In 264, Zhong Hui started plotting his rebellion to expel Sima Zhao and take the empire [60]. His plan was to send Jiang Wei with the vanguard to Chang’an through Ye valley. Once the west was taken, Zhong Hui would send the armies through river and land onto Luoyang and thus have free access into the Central Plains [61].

Sima Zhao was suspicious of Zhong Hui from the beginning though [62], and with the pretext that he feared Deng Ai would not accept his arrest, he sent Jia Chong through Ye valley into Luocheng, while he himself stationed at Chang’an with a large force. Zhong Hui was alarmed at this new development, but found some respite with the thought that even if he failed he could still survive in Shu, just like Emperor Zhaolie had done in days of old [63].

Zhong Hui summoned the different officials in mourning service of Lady Guo, and had a petition allegedly written by her compelling him to destroy Sima Zhao. Declaring himself inspector of Yi province, he forced the attending officers to comply and held them under house arrest in the government buildings used by Han [64].

Jiang Wei had his own designs and urged Zhong Hui to slaughter the Wei officers. His plan was to use the army given to him by his associate to kill him and restore the Emperor to his rightful throne. Zhong Hui hesitated [65].

During this time, the rumor spread that Zhong Hui indeed intended to slaughter the officials, and when the invading troops heard of this, they mutinied. Entering Chengdu, they liberated the prisoners and attacked Zhong Hui. Facing complete annihilation, Jiang Wei decided to face with death with bravery and charged at the enemy troops [66]. Despite his advanced age, Jiang Wei struck down several enemy soldiers [67]. His death by the side of the man he was planning to betray marked the end to Jiang Wei’s chaotic life.

Historical Appraisals

Appraisals on Jiang Wei are surprisingly varied with some relevant ones in his own wikipedia article with decent translations. Chen Shou himself considered him a man of both Wen and Wu, that is to say a cultured man yet skilled in warfare. Despite this, he was careless, anxious to achieve merit and wantonly mobilized the people and thus brought his own destruction [68].

Sun Sheng’s comment on Jiang Wei is a lot more negative, scathing. Seriously, read this:

Although scholar-officials may take different paths and have different goals, they should live by the four fundamental values of loyalty, filial piety, righteousness and integrity. Jiang Wei was originally from Wei yet he defected to Shu and betrayed his ruler for personal gain. Therefore, he was disloyal. He abandoned his family to lead a meaningless life. Therefore, he was unfilial. He also turned against his native state. Therefore, he was unrighteous. He lost battles but chose to live on. Therefore, he had no integrity. When he was in power, he failed to establish himself as a virtuous leader and instead brought untold suffering to the people by forcing them into a prolonged war to boost his personal glory. Although he was responsible for defending his state, he ended up provoking the enemy and lost his state. Therefore, he was neither wise nor courageous. Jiang Wei possessed not a single one of these six values. In reality, Jiang Wei was nothing more than a traitor to Wei and an incompetent head of government to Shu, yet Xi Zheng said he was worthy of serving as a role model. How absurd is that. Even though Jiang Wei may be studious, that is just a good habit rather than a praiseworthy virtue. That is no different from a robber taking his due share of the loot, and no different from Cheng Zheng pretending to be humble.

Translation from Jiang Wei’s wikipedia entry.

These words are absurd. It even feels like Jiang Wei stole Sun Sheng’s wife or something, because even the virtuous Jiang Wei had that couldn’t be spun around and interpreted as some heinous crime, he disregard as something that should be the bare minimum (sound familiar?).

Pei Songzhi has a much more positive view of Jiang Wei and counters Sun Sheng’s points one by one. I will summarize his points when I give my personal opinion later [69].

Several of Jiang Wei’s contemporaries also appear to have had a positive view of the man. Deng Ai considered him a hero of the times [70], Cao Huan thought that he was the only person the Han could rely on [71], Zhong Hui had a very high opinion of him, comparing him to people like Xiahou Xuan, another respected and popular figure of Wei [72] and naturally Zhuge Liang as well considered him a talented individual [73].

Liao Hua and Qiao Zhou were critical of his foreign policy [74], but otherwise were not as harsh on the man as a person.

Hu Sanxing thought Jiang Wei was dedicated fully to the cause of Han, that he must have been intelligent and able to manipulate Zhong Hui for his country, disagreeing with Chen Shou and Sun Sheng’s opinion [75].

Lastly, I want to cite Xi Zheng’s appraisal, found in Jiang Wei’s own bio:

Jiang Boyue held the responsibilities of a top general and occupied a high position in the government, yet he lived in a plain-looking residence, had no other income besides his salary, had only one wife and no concubines, and had no form of entertainment. His clothes and transport were just sufficient for use; he also imposed restrictions on his meals. He was neither extravagant nor shabby. He kept his spending within the limits of his state-issued allowance. His purpose in doing so was neither to prove that he was incorruptible nor to resist temptation. He did so ungrudgingly because he felt satisfied with what he already had. Mediocre people tend to praise those who achieve success and condemn those who fail; they praise those of higher status than them, and condemn those of lower status than them. Many people hold negative views of Jiang Wei because he died in a terrible way and his entire family was killed. These people do not look beyond the superficial. They fail to grasp the true meaning of appraisal as set out in the Spring and Autumn Annals. Jiang Wei’s studiousness, as well as his modesty and humility, make him a role model for his contemporaries.

Translated from Jiang Wei’s wikipedia page.

This appraisal is what triggered a response from Sun Sheng. This shows us a more personal side to Jiang Wei, a side that shows his humility, his frugality and his studious nature.

My personal opinion

I have quite a high opinion of Jiang Wei. I find his personality traits quite admirable. He was humble, he was loyal and he was incredibly dedicated, tenacious to the extreme. It kind of reminds me of Liu Bei in the way he refused to give up. Even in the face of absolute annihilation he decided to fight for what he truly believed in, never ceasing in his efforts, no matter the odds.

However, you didn’t read my lengthy writeup pretty much covering his entire military career for me to talk about Jiang Wei’s quality as a man. His military record was mixed, but his military talents still shine through his shortcomings. Not only was he praised by some very competent contemporaries like Deng Ai, Zhuge Liang or Zhong Hui, but he showed remarkable tactical prowess and ingenuity. He cleverly stopped Sima Yi’s pursuit at Wuzhang plains, was an integral part of Jiang Wan’s northern strategy, successfully agitated the Qiang and Hu barbarians, slaughtered Xu Zhi, crushed Wang Jing and shook the western border to the point where even Deng Ai considered him a considerable threat.

Despite my respect and admiration for Jiang Wei, I think it wouldn’t be fair to ignore his flaws. He sometimes displayed a significant degree of recklessness. He ended up campaigning every year late on his career, exhausting the resources of Han in campaigns that didn’t yield significant results that could swing the war in his favor. I think Shanggui was his biggest failure, as I can’t really think of a reason why he would engage Deng Ai with hungry troops once he realized Hu Ji didn’t arrive. It was a very dumb mistake.

According to the Han Jin chunqiu, Xue Xu, an envoy from Wu, remarked that Han was impoverished and the people had a hungry look on their face, with a foolish ruler at the helm. While I have been told Pei Songzhi interpreted this annecdote was an analogy to criticize Sun Xiu and the state of Wu at the time, I don’t think it negates the state of Han either. Jiang Wei, despite this pitiful state of civil affairs, constrained the people and the resources of the Shu region, making his fruitless campaigns all the more damaging. While many of them didn’t end in significant losses of life, maintaining and mobilizing those armies must not have been a cheap endeavor, and the end result was a weakening of his country despite his best intentions.

This, of course, wasn’t helped by the situation at home. The rise of Huang Hao meant that those who favored him would see appointments, while those whom he disliked would be his targets. I can’t however fault Jiang Wei for that. He was not in charge of the administration. He was not a politician and it was not his job to govern the state. It is unfortunate that later in his life he would always return to a state dominated by Huang Hao and his cronies, a court that was divided and tired of war, as the local gentry lacked the drive to move out of Shu and was involved in a tug of war with Jiang Wei and the more expansionist clique. It was a far cry from Zhuge Liang’s regency, and if the country were to be managed more competently, perhaps Jiang Wei would have found more success. Killigrew also emphasizes Han’s factionalism and mismanagement as opposed to the Sima’s increasing unity.

While Chen Shou criticized Jiang Wei’s warmongering because the Han was a small state, I heavily disagree with this conclusion and that of his detractors. Precisely because the Han was a small state, it couldn’t afford to wait it out. Wei would win the long game, it really is that simple. Zhuge Liang saw this, Jiang Wan saw this and Zhuge Ke explicitly remarked this. Invading north was the only way the Han could viably survive, not accumulating resources waiting for a state that will outresource you by a wider margin the longer you wait.

He truly was unfortunate, as his career started taking off after Zhuge Liang died. While Jiang Wan was open to the idea of giving him important roles in a grand campaign, Fei Yi was uneager to push and expel Wei, and when he finally came to dominate the army, the political situation was already devolving into bickering between the different factions. Campaigning north meant having less pressence to influence court politics at home, and this situation Jiang Wei couldn’t overcome. Alas, Heaven was not on his side.

Then there is his controversial plan to defend the Han. The plan ultimately failed, and he deserves criticism for that. The execution was not as good as it could have been, and people like Killigrew remark that Tazhong was too far from Hanzhong to speedily reinforce it. Despite this, Pei Songzhi praises the plan and thinks it was almost successful. The daring nature of Deng Ai’s march cannot be understated: it was borderline suicidal. If Zhong Hui had retreated, Jiang Wei could have had his desired great victory against Wei, mortally wound the reputation of Sima Zhao and send a detachment to destroy Deng Ai. His plan had flaws, flaws that were skillfully exploited by Zhong Hui, but nonetheless it was very close to success and perhaps it would have cemented Jiang Wei’s place in history as one of the greats. But because his plan failed while Deng Ai’s succeeded, it is the latter that gets his brilliant reputation (which is still deserved in my opinion, but not entirely because of his plans in the invasion of Han).

Despite his flaws, Jiang Wei was a man of exceptional ability, loyalty and determination. I can’t help but compare him with Wei Yan. Like him, Jiang Wei was brave and daring, a resourceful strategist and a capable commander of men. The key difference is that Jiang Wei was infinitely more humble and actually loyal. It truly is a pity the Chancellor couldn’t employ Jiang Wei earlier.

Jiang Wei is a tragic figure that had to play his role as the last hero of the Han dynasty, finally being swallowed by the necessities and circumstances of the time. May his sacrifice be forever remembered.

References

Part 1:

1: SGZ, Jiang Wei’s biography.

2: ibid

3: Fuzi, annotation on Jiang Wei’s SGZ biography.

4: SGZ, Jiang Wei’s biography.

5: Weilve has it: Now, after the Emperor Liu Bei had died, complete quiet had reigned in Han for some years, so Wei had not made any preparations at all. Hearing of suddenly

Zhuge Liang’s exodus, both the court and the country at large were frightened and awed.

Translation from Achilles Fang.

6: The letter can be found in Jiang Wei’s biography on the SGZ.

7: SGZ, Jiang Wei’s biography.

8: Obviously, Han Jin chunqiu. Found in Achilles Fang’s Chronicles of the Three Kingdoms.

9: SGZ, Jiang Wei’s biography.

10: ibid.

11: ibid.

12: ibid.

13: ibid.

14: SGZ, Jiang Wei’s biography.

15: SGZ, Guo Huai’s biography.

16: As he would lately remark in his exhortations to Fei Yi.

17: SGZ, Jiang Wei’s biography.

18: He suppressed the barbrians at Wenshan and Pingkang in 247, as his own SGZ biography states.

19: These uprisings were not the ones he had suppressed earlier that year, as this was Wei territory.

20: Huayang guozhi has it: Wei came to Longxi, with Wei generals Guo Huai and Xiahou Ba battled, defeating them. 维出陇西,与魏将郭淮、夏侯霸战,克之。 My translation.

21: SGZ, Guo Huai’s biography.

22: This description of events was summaized from Achilles Fang’s Chronicle of the Three Kingdoms. The different sources include the biographies of Chen Tai and Liu Shan.

23: SGZ, Deng Ai’s biography.

24: Han Jin chunqiu.

25: Biographies of Dong Yun and Chen Zhi on the SGZ.

26: Dong Yun and Chen Zhi’s SGZ tell use that Huang Hao bribed Deng Ai’s men to be let go when he was arrested after the surrender of Chengdu. Having accumulated great wealth, it’s clear Huang Hao was not in the least interested in running a state properly.

27: SGZ, Jiang Wei’s biography.

28: ibid

Part 2:

1: Chronicles of the Three Kingdoms, Achilles Fang.

2: SGZ, Jiang Wei’s biography. ZZTJ mentions he was besieging Didao, but his owne biography mentions Nan’an, so that’s the one I decided to write in.

3: Yu Song explained to Sima Shi that Jiang Wei seeked to take the wealth from the Wei border and thus didn’t bring many provisions. His full evaluation of the situation can be found in Chronicles of the Three Kingdoms.

4: SGZ, Zhang Ni’s biography.

5: ibid.

6: ibid. I am assuming the battle described in Zhang Ni’s biography against Xu Zhi is the same and the one Jiang Wei lead against Xu Zhi, Zhang Ni being a subordinate officer and performing well.

7: ibid. It’s not entirely clear if it was Zhang Ni who personally killed many or if it was his regiment because of Zhang Ni’s tactics. Regardless, Zhang Ni performed exceptionally and was put to great use.

8: SGZ, Jiang Wei’s biography. The original line is 进围襄武,与魏将徐质交锋,斩首破敌,魏军败退。, “Besieging Xiangwu county, (Jiang Wei) with Wei general Xu Zhi engaged, cutting heads and breaking the enemy, Wei’s troops withdrew in defeat”. My translation.

9: Chronicles of the Three Kingdoms

10: SGZ, Jiang Wei’s biography.

11: ibid.

12: SGZ, Zhang Yi’s biography.

13: Chronicles of the Three Kingdoms.

14: SGZ, Jiang Wei’s biography.

15: Chronicles of the Three Kingdoms. He is noted to have advanced with Ten thousand men. Since Cao Xiu successfully escaped, he didn’t lose all ten thousand, but still was a significant defeat.

16: Chronicles of the Three Kingdoms. It cites “tens of thousands”.

17: SGZ, Zhang Yi’s biography.

18: Chronicles of the Three Kingdoms.

19: ibid. The various generals all said, “Wang Jing

was recently defeated and the Shu hordes are too strong. You, General, with your motley

troops have succeeded to a defeated army and will confront the keen edge of the victorious

enemy; this will not do at all".

20: Chronicles of the Three Kingdoms. Wang Jing sighed and said, “We have been cut

off from provisions for the past ten days. Had reinforcements not come speedily, the entire

city would have been butchered and rent asunder, and the whole province overthrown.”

Being cut off from supplies, his own reserves couldn’t hold the fight for long.

21: See 19.

22: Chronicles of the Three Kingdoms. Deng Ai, said, “At the defeat on the west of the Tao, our loss was not small; our officers and men are worn out and depleted, our granaries are

empty, and the population is wandering homeless. We are almost reduced to ruin.”

23: ibid.

24: Chronicles of the Three Kingdoms. The source in question is the Zhanlve of Sima Biao, that states: “Jiang Wei penetrated into our territory without waiting for the baggage to arrive. His men suffered from hunger and his army was thus overthrown at Shanggui.”

25: Chronicles of the Three Kingdoms. Deng Ai planned out appropriate measures; loyally and bravely he exerted himself, killing tens of their

generals and decapitating thousands of their men.

26: SGZ, Jiang Wei’s biography.

27: Chronicles of the Three Kingdoms.

28: ibid.

29: SGZ, Jiang Wei’s biography.

30: Chronicles of the Three Kingdoms. “One will burn himself with military weapons if he does not lay

them aside. I am referring to Jiang Boyue (i.e. Jiang Wei). His sagacity does not surpass

that of the enemy, and his strength is less than the enemy’s. Still he would use them (the

weapons) immoderately. How is he going to preserve himself?“

31: ibid.

32: ibid.

33: ibid.

34: ibid.

35: ibid.

36: ibid. However, the original text of the ZZTJ mentions Cao Shuang lost a significant degree of men. As Achilles Fang points out, this was rewritten by Sima Guang and the original reference cites a loss of cattle for transporting supplies.

37: ibid.

38: ibid. The various officials held the appearance of the dragons in the wells to be an auspicious

sign. The Emperor said, “Dragons symbolize the virtue of a sovereign. But they are not in

heaven above, nor in the fields below; in their frequent appearances they are being

constricted in wells. This is not an auspicious omen.” He composed a poem on a dragon lying

hid in allusion to himself. Sima Zhao saw it and was displeased.

Cao Mao was clearly unsatisfied with Sima Zhao’s blatant political moves. It’s not likely he would voluntarily insist in Sima Zhao receiving a dukedom and the Nine Bestowments.

39: Killigrew, 2001.

40: Chronicles of the Three Kingdoms. It mentions Zhong Hui having some ten odd myriads of men. In Chinese, 十万 can also be the number 100.000.

41: Jiang Wei’s number of men was taken from Killigrew, 2001. The story about Huang Hao was taken from Chronicles of the Three Kingdoms.

42: Killigrew, 2001.

43: ibid.

44: Chronicles of the Three Kingdoms.

45: ibid.

46: Killigrew, 2001.

47: Chronicles of the Three Kingdoms.

48: ibid.

49: ibid.

50: ibid.

51: ibid.

52: ibid. The Shangshu lang Huang Chong was a son of Huan Quan. He repeatedly advised Zhuge Zhan to hasten forward and occupy the defiles, to

keep the enemy from entering level terrain. Zhuge Zhan continued to hesitate without

accepting his advice.

53: ibid.

54: ibid. Deng Ai said, “To be or not to be depends on this one stroke. How dare you say they cannot be beaten?”

55: ibid. Zhuge Zhan was mediocre, but Zhong Hui thought highly of him. Jiang Wei being compared to him is not meant as criticism.

56: Ibid. Following the precedent of Deng Yu, he presumed Imperial authority and appointed Liu Shan, the Sovereign of Han, to be acting piaoji jiangjun, the Crown Prince to be fengche (duyu) and the various officials princes of the blood to be fuma duyu. As for the various officials of Han, he appointed them, in accordance with their different ranks, as subordinate officials either of the Prince Liu Shan or of Deng Ai himself.

57: ibid.

58: ibid.

59: ibid.

60: ibid.

61: ibid.

62: Killigrew, 2001. Sima Zhao was warned of Zhong Hui’s disloyalty, but decided to use him anyway as only he was in favor of campaigning west, using Zhong Hui’s ambition to ensure victory.

63: Chronicles of the Three Kingdoms (although Zhong Hui used the Emperor’s personal name).

64: ibid.

65: ibid.

66: ibid.

67: ibid.

68: Jiang Wei was proficient in civil and military affairs, and he desired to attain personal glory and leave his name in history. However, he lacked foresight and good judgment when he chose a path of warmongering, and that resulted in his downfall. As Laozi once said, ‘governing a state is like cooking a small dish.’ Shu was a small state, so all the more he should not have continuously disturbed it.

Found on wikipedia’s article on Jiang Wei.

69: Pei Songzhi’s comment:

When Zhong Hui and his massive army attacked Jiange, Jiang Wei and his officers led their troops to put up a solid defence. When Zhong Hui wanted to retreat after failing to breach Jiange, Jiang Wei nearly gained the glory of successfully defending Shu from an invasion. However, Deng Ai took a shortcut, bypassed Jiang Wei, defeated Zhuge Zhan and conquered Chengdu. If Jiang Wei turned back to save Chengdu, Zhong Hui would attack him from the rear. Under such circumstances, how could he possibly achieve both goals? People who criticise Jiang Wei for not turning back to retake Mianzhu and save the emperor are being unreasonable. Zhong Hui later planned to execute all the Wei officers who opposed his rebellion and put Jiang Wei in command of a 50,000-strong vanguard force. If everything went according to plan, all the Wei officers would have been executed and Jiang Wei could have seized military power and killed Zhong Hui, and thus it would not have been too difficult for him to restore Shu. When great people made remarkable achievements while others least expected it, they receive praise for creating miracles. When unforeseen circumstances ruin a plan, it does not mean that the plan was a bad one to begin with. If an unforeseeable condition caused Tian Dan’s "fire cattle columns” tactic to fail, would people say that he was foolish?“

70: Chronicles of the Three Kingdoms. Jiang Wei is indeed a hero of the time; it is because he had to deal with me that he is reduced to this extremity.

71: 蜀所恃赖,唯维而已。

72: See 55.

73: See part 1 of this article.

74: Chronicles of the Three Kingdoms records Liao Hua’s comment and Qiao Zhou’s memorial.

75: 姜维之心,始终为汉,千载之下,炳炳如丹,陈寿、孙盛之贬,非也。

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Evaluating Wu: Zhuge Liang's campaigns parts 1 and 2

I’m not going to tell you who Zhuge Liang is because everyone knows who he is. I would say he’s the most famous character in this story, or at least on par with Cao Cao. A brilliant man, Zhuge Liang was enfeoffed as the Loyal and Martial Marquis (Zhongwuhou, 忠武侯). This is exactly what we’re going to talk about, the wu in Zhuge Liang’s title, the military career of the Marquis. I have decided to split the piece in 2 parts so as to not make it too long. In this first one I will describe Zhuge Liang’s career until the end of the Third Northern Campaign, and part 2 will talk about Wei’s invasion and Zhuge Liang’s final 2 campaigns, as well as my appraisal once the context of each and every campaign has been explained. Let us go.

The Northern Campaigns is definetely my favorite part of this time period, and I will talk about them properly. However, let’s briefly introduce Zhuge Liang’s first campaign.

Zhuge Liang’s military career starts at around the year 215, when Liu Bei was besieging Chengdu. The Marquis led the multiple armies from Jingzhou upstream from the Changjiang, sending the two generals Zhang Fei and Zhao Yun to take Jiangzhou and Jiangyang, respectively. They then moved on to Chengdu, whereby they united with Liu Bei’s troops (SGZ 35). That’s it.

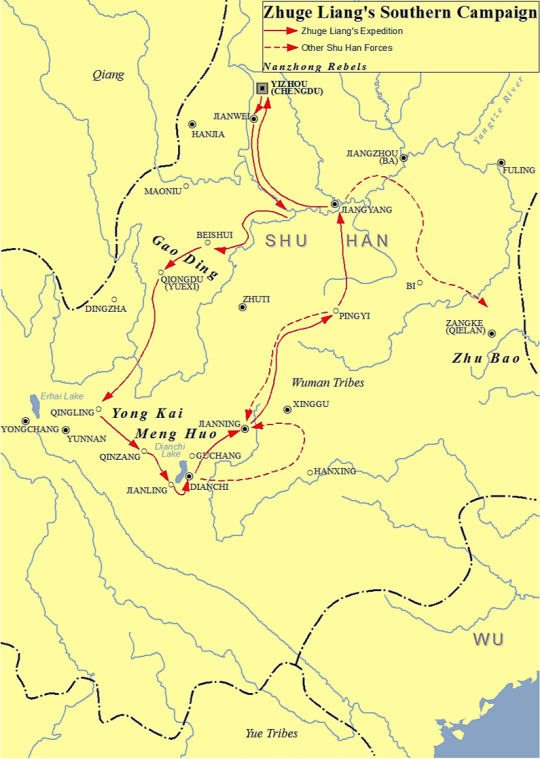

The Southern Campaign of 225

A more significant campaign was his Southern Campaign. Previously, at the death of Zhaolie, Yong Kai used the tensions between the tribes and the Han government to rebel in the south. He joined up with king Gao Dingyuan of the Sou tribes and Zhu Bao in Zangke commandery. As a result, the commanderies of Zangke, Yizhou and Yuexi were in rebellion. The ZZTJ also mentions that there were 4 commanderies in rebellion, so perhaps Yongchang in the far south was one of them as well.

The rebellion wasn’t put out immediately, and the Marquis decided the better strategy was to rest the people, gather supplies and train the soldiers.

Zhu Bao, the Grand Administrator (taishou) of Cangke, and Gao Ding, the King of the barbarians at Yuehui, both revolted and responded to Yong Kai. Because of the recent death of the Emperor of Han, Liu Bei, Zhuge Liang temporized with them all and did not dispatch a punitive expedition against them. He paid attention to agriculture in order to increase production; he closed the passes in order to give rest to the people. Only when the people were put as ease and provisions became abundant did he employ them.

Chronicles of the Three Kingdoms, Achilles Fang (ZZTJ)

In 225, Zhuge Liang’s preparations were complete and he launched his southern campaign. Zhuge Liang’s strategy was to invade the rebels from three separate directions: He himself would go west to Yuexi, Li Hui south to Yizhou and Ma Zhong east to Zangke.

Zhuge Liang marched on river, and upon his arrival at Yuexi, he camped at Beishui. His strategy was simple: he had hoped to wait the enemy to gather their forces in one place so that he could defeat them in a decisive engagement and crush the rebellion in one blow. Gao Dingyuan prepared his defense at Maoniu and Yong Kai also wished to engage the Chancellor.

The plan went better than expected when Gao Dingyuan had Yong Kai assassinated and Meng Huo, a man that held considerable influence over the southern peoples, was named leader of the rebellion.

With a new leader taking over, Zhuge Liang made use of this new development to strike at Gao Dingyuan’s forces, greatly defeating him. He was then captured and executed.

I have seen other people narrate this particular incident as follows: Gao Dingyuan and Yong Kai join up at Yuexi, Gao Dingyuan kills Yong Kai and then Gao Dingyuan surrenders to Zhuge Liang, after which is executed. This is false, as the sources only claim the following:

The troops of Gao Ding-Yuan killed Yong Kai and others, including gentry and common people. Meng Huo succeeded Yong Kai as ruler. Zhuge Liang put Gao Ding-Yuan to death.

Huayang Guozhi as written in the Chronicles of the Three Kingdoms, Achilles Fang.

At no point it is mentioned that Gao Dingyuan surrendered to Zhuge Liang. The following passage goes into more detail:

后主建兴元年(223),杀郡将军焦璜,举郡称王,与益州郡雍闿相呼应。三年三月,当诸葛亮帅兵南征时,率属下自旄牛(今四川汉源县)、定筰县(今四川盐源县)至卑水(今四川美姑县至宁南县中间地区)置垒抗拒,并获雍闿军援。后彼此矛盾,使部曲杀闿。七月,被蜀军击败,为诸葛亮所杀。

On the inaugural year of Jianxing (223) during the reign of the Later Sovereign, he killed the garrison commander Jiao Huang, named himself king and worked with Yong Kai of Yizhou. On the third month on the third year, when Zhuge Liang was leading men on an expedition south, he led his men from Maoniu (today’s Hanyuan county in Sichuan), Dingzuo county (today’s Yanyuan county in Sichuan) to Beishui (today’s area between Meigu and Ningnan counties) and established defenses to repel the enemy, also receiving reinforcements from Yong Kai. Later they had a disagreement and with his troops killed Yong Kai. On the Seventh Month, he was attacked and defeated by the troops of Shu, killed by Zhuge Liang.

Historical Dictionary of China’s Minority Peoples, page 1915, Gao Wende. My translation.

Meanwhile, Ma Zhong successfully defeated the rebels of Zhu Bao at Zangke and quickly pacified the commandery, while Li Hui was surrounded and outnumbered at Yizhou. Li Hui managed to break free using a clever ruse by which he pretended to surrender. The rebels believed him, for he was isolated from the rest of the army, so they relaxed the encirclement. Li Hui violently charged and marched to Zangke, joining with Ma Zhong.

The southerners believed this, so the besiegers became neglectful. Therefore Huī went out and attacked, and greatly defeated them, and immediately pursued the defeated men south to the river Pán, to the east joining the forces at Zānggē and restoring communication with Liàng.

Biography of Li Hui, translated by Yang Zhengyuan

Zhuge Liang marched to Dianchi and defeated Meng Huo. The Annals of Han and Jin describe how Meng Huo was captured 7 times, but it’s unlikely his men would have let him lead after being captured 7 times.

Regardless of the details, the south was pacified and Zhuge Liang treated the southerners with leniency, appointing the locals to fill administrative posts.

Some one advised Zhuge Liang against this measure. Zhuge Liang said, “If we leave behind outsiders, we must also leave soldiers with them, and the soldiers back there will not have any provisions. This is the first difficulty. Then, the barbarians have lately suffered injury and destruction, their fathers and elder brothers being killed. Leaving behind outsiders and no soldiers would be certain to bring calamity. This is the second difficulty. Lastly, the barbarians have frequently committed the crime of deposing and killing governors and they are aware how serious their misdeeds are. If we leave behind outsiders, they will never be at ease. This is the third difficulty. Now I intend to leave no soldiers behind nor transport provisions, and yet to bring about the same government and to make both the barbarians and the Chinese live more or less peacefully with each other. Hence my measure.”

Annals of Han and Jin

This is just as Ma Su had adviced prior to Zhuge Liang’s depart:

Xiāngyángjì states: Jiànxīng third year [225], [Zhūgě] Liàng campaigned against Nánzhōng. Sù escorted him for several tens of lǐ. Liàng said: “Though we have made plans together for many years, now I can again ask you a favor for a good plan.” Sù answered: “Nánzhōng relies on its rugged terrain and distance, and has been disobedient for a long time. Even if today they are defeated, tomorrow they will again rebel and that is all. Now you lord are about to gather the whole state for a Northern Expedition to deal with powerful rebels [Wèi], so they [the Nánzhōng rebels] will learn the government’s authority is weak inside [while Zhūgě Liàng is away in the north], and their rebellions will also accelerate. If all their tribes and kinds are exterminated to remove future worry, that is not the way of the benevolent, and moreover could not be done quickly. In the way of using troops: attacking the heart is best, attacking cities is worst; hearts battling is best, soldiers battling is worst. I hope you lord will focus on subduing their hearts and that is all.” Liàng accepted this plan, and pardoned Mèng Huò to comfort the south. Therefore to the end of Liàng’s life, the south did not dare again rebel.

Biography of Ma Liang, translated by Yang Zhengyuan.

It’s important to note that the last sentence is not correct. Trouble in the region did not stop in its entirety.

Through the use of good tactics, Zhuge Liang quickly broke the rebel forces. I would also like to bring attention to Zhuge Liang’s choice of personnel. Li Hui proved to be a resourceful and courageous warrior, and shortly after the troops left, he successfully quelled further unrest in the region.

Ma Zhong, more importantly, was also an excellent choice, because not only was he capable, he was also politically conscious:

Third year [225] Liàng entered the south and appointed Zhōng as Administrator of Zāngkē. The prefecture Deputy Zhū Bāo rebelled. After the rebellion, Zhōng brought relief and reasonable government, and deeply had authority and kindness.

Biography of Ma Zhong, translated by Yang Zhengyuan

Ma Zhong was well aware of the strategy to be followed and continued the policy of leniency as laid out by Ma Su before the campaign.

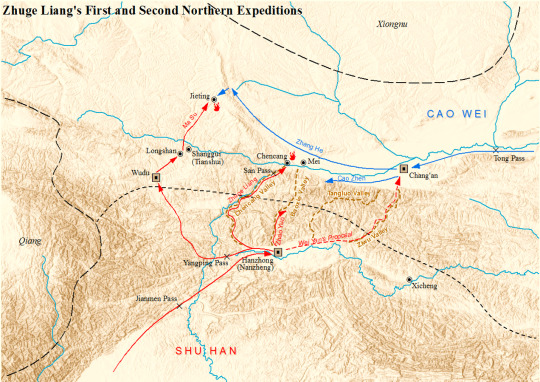

The First Northern Campaign, 228

In the year 226, the usurper Cao Pi succumbed to illness, leaving Cao Rui on the throne. With troubles with the Qiang tribes brewing in the western frontier of Wei, Zhuge Liang decided it was the appropriate time to launch his campaign and march from Hanzhong on 228. He previously contacted Meng Da so that he may join him in coordination with his campaign, but he was attacked and killed by Sima Yi.

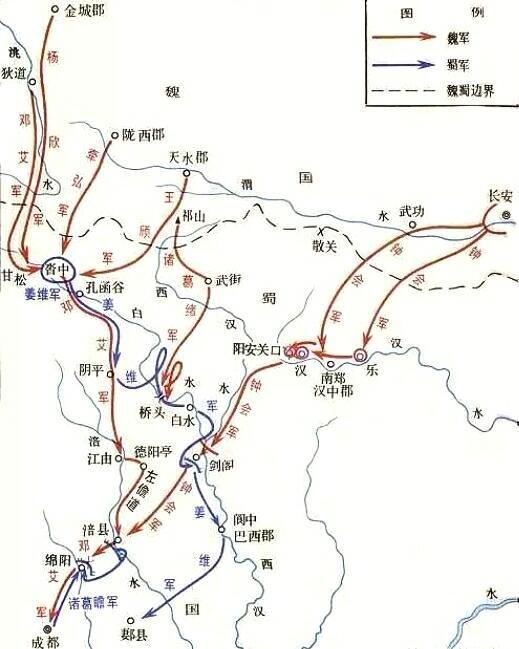

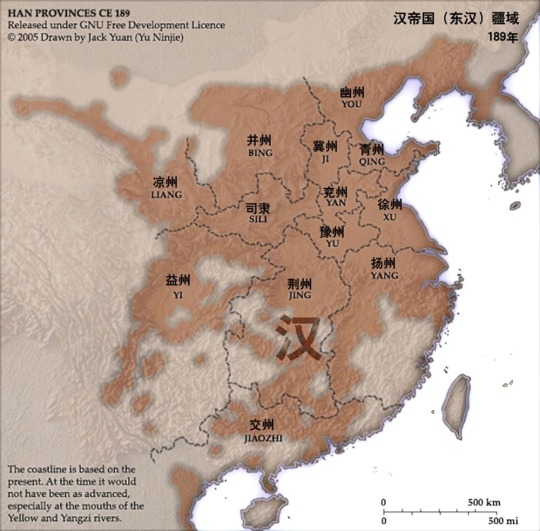

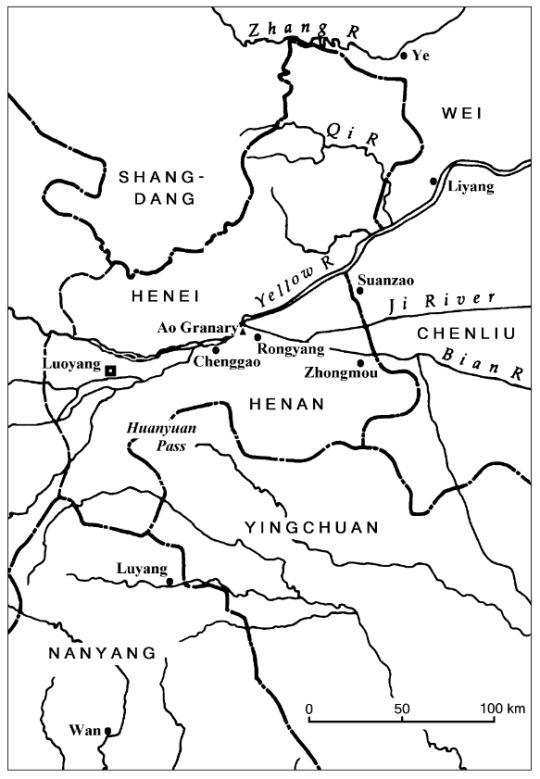

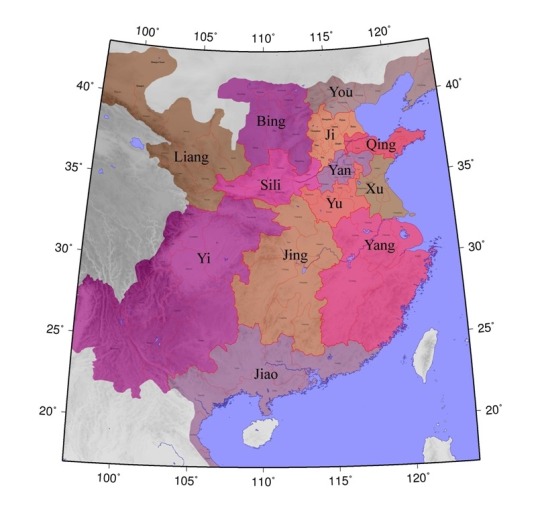

Let us look at a map of the Han-Wei border to discuss maneuvers:

Ignore Zhuge Liang’s arrow moving to Chencang for now. Zhuge Liang’s strategy was to march from Mount Qi into the west of Liang and the Wei River valley. This area is known as Longyou (west of Long Mountain). In order to accomplish this, he wanted to have General Zhao Yun and Deng Zhi march towards Mei as a decoy force, while the main army under the Chancellor moved towards Longyou.

The arrow on the east, as it is stated there, is indeed Wei Yan’s rejected proposal. I have already talked about this plan here. I criticized his plan as not being viable due to the difficulty of retreat caused by harsh terrain, as well as the defensive nature of Chang’an. Wei Yan requested 10 thousand veteran troops to march them through the valley and attack Chang’an with this surprise maneuver, hoping the presumably cowardly Cao Mao would flee in terror upon seeing him.

I have somewhat warmed up to this proposal. I still think it is not viable: 10 thousand men is too few a number for taking Chang’an, and if it fails it would mean the end of both Wei Yan and his army. However there is some merit to the attitude displayed here. I will elaborate on this later.

The Weilve states:

Now, after the Emperor Liu Bei had died, complete quiet had reigned in Han [i.e., in Shu] for some years, so Wei had not made any preparations at all. Hearing of suddenly Zhuge Liang’s exodus, both the court and the country at large were frightened and awed.

Weilve, Chronicles of the Three Kingdoms by Achilles Fang as seen in passage 6 of year 228 (ZZTJ)

Zhuge Liang’s invasion shook the west and as a result, the commanderies of Anding, Tianshui and Nan’an revolted in favor of the Han.

It is in this moment when Zhuge Liang made the biggest mistake of his entire military career. Advancing to the Longyou area, he had Ma Su act as the vanguard. Ma Su camped at Jieting, and faced off against Zhang He’s troops.

Ma Su had camped on a hill, cutting off his own water supply. Zhang He easily encircled the enemy and dealt a devastating defeat to Ma Su. It was the actions of Wang Ping that earned the most merit, as Wang Ping was the only general to orderly retreat and rally the scattered troops back home.

The army was completely scattered, and only Píng’s command of a thousand men, shouted and drummed to maintain themselves, and Wèi General Zhāng Hé suspected there were hidden troops, and did not pursue. Therefore Píng slowly gathered the scattered camps to escape, leading the officers and soldiers back.

Biography of Wang Ping, translated by Yang Zhengyuan

With the defeat at Jieting, the campaign was called off. General Zhao Yun and Deng Zhi were both defeated. This is no surprise, as they were to be used as decoy forces and thus their objective was to pin down Cao Zhen at Mei while the main army took Longyou. Thanks to the command of General Zhao Yun, the decoy force safely withdrew without suffering significant losses, for which he was commended (SGZ 36, biography of Zhao Yun). The population of the rebelling counties followed the Marquis back home as well.

Killigrew brings attention to Zhuge Liang’s inability to reinforce Ma Su despite not being too far away from Jieting, and the ZZTJ describes Zhuge Liang arriving but being unable to take any positions, meaning that he had arrived too late.

After the failed incursion into enemy land, Zhuge Liang then memorialized the throne and requested his demotion:

“The fault is mine in that I erred in the use of officers. In my anxiety I was too secretive. The ‘Spring and Autumn’ philosophy has pronounced the commander such as I am is blameworthy, and whither may I flee from my fault? I pray that I may be degraded three degrees as punishment. I cannot express my mortification. I humbly await your command” So the emperor demoted Liang to General of the Right but acts as the Prime Minister and commands the army as before.

Biography of Zhuge Liang, translated by Lucy Zhang and stephen So.

In contrast to his southern campaign, Zhuge Liang’s first expedition against the northern rebels did not show a particularly good choice of personnel. General Zhao Yun was used effectively, as by his command the decoy force was secured and suffered no major setbacks, essentially fulfilling his role properly.

However, in hindsight, the choice of Ma Su was a really bad one. He disobeyed Zhuge Liang’s orders (ZZTJ, year 228 passage 11 of Chronicles of the Three Kingdoms) and did not listen to Wang Ping’s admonitions, making his already difficult situation even more precarious.

Using Zhuge Liang’s perspective the choice of Ma Su was not entirely unwarrented. He trusted the man and he had proven to be a pretty intelligent fellow if his southern strategy is anything to go by.

I am not going to be dishonest, though. Even if we take Zhuge Liang’s perspective into account, the choice of Ma Su simply does not work. Regardless of his talents, Ma Su was not experienced in warfare and he had to go up against Zhang He, one of the most veteran rebel officers in the land.

Ma Su’s tactical mistakes and conceit are his own, but he should not have been put in such a position to begin with. It is no surprise that Ma Su was defeated. This is a rare case of Zhuge Liang engaging in nepotism. It is clear to me that the fondness he had for Ma Su played an important part in this choice. And yes, Ma Su was an intelligent man. But being intelligent is honestly not the most important thing. Yuan Shao could have been a king among hegemons if he just had some more humility and acted more quickly. Ma Su certainly had the necessary gifts, but he did not cultivate them before he was thrown in a position of certain defeat.

Ironically, Ma Su’s closeness to Zhuge Liang spelled his doom, as Zhuge Liang clearly saw the error of his ways and had Ma Su executed. This is in line with Zhuge Liang’s legalist inclinations: the law had to be upheld, and he had to be particularly harsh with Ma Su precisely because he was his close friend. If those close to the Chancellor could get away with disasters of that nature, martial discipline would not be upheld and the troops will be loose and insubordinate.

There is a famous anecdote about Sunzi, author of the Art of War, that I think is quite fitting in this context. The story goes, roughly like this: the king summons Sunzi and asks him about his lessons and whether or not they could be applied to women. When Sunzi said that his teachings could indeed be applied to women, the king then gave him “command” over his concubines.

Sunzi divided the concubines into two groups and assigned one of the king’s favorites to command each group.

When Sunzi began the drill and his orders were not obeyed even after being repeated several times, he arrived to the conclusion that his orders were indeed quite clear, and the subordinate “officers”, in this case the leading concubines, were being too lax on discipline.

Sunzi had these “officers” executed immediately and appointed new ones. Both groups performed the drill with perfect precision.