Text

When you step into sunlight, you honor Apollo. When you admire the moon, you honor Artemis. When you admire cloud shapes, you honor Hera. When you smell petrichor, you honor Zeus. When you laugh at a joke, you honor Hermes. When your body twitches to dance at a particularly upbeat music, you honor Dinoysus. When you enjoy the first bite of your breakfast, you honor Demeter. When you choose your peace over any conflict, you honor Athena. When you warm yourself up by sheltering yourself in blanket, you honor Hestia. When you listen to Ocean sounds, you honor Poseidon. When you smell flowers, you honor Persephone. When you admire the coolness of first day of Autumn, you honor Hades. When you wear your favourite jewellery, you honor Hephaestus. When you smile, you honor Aphrodite. When you exercise, you honor Ares. When you light a torch in a dark room, you honor Hekate.

Your body is a shrine to Gods, your being an act of devotion for them. You, by yourself, are enough for them.

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

The 7 Pillars of Hellenism.

Xenia - This is the pillar that signifies hospitality, generosity and reciprocity. It's typically demonstrated in a guest/host dynamic.

Kharis - This is the pillar that signifies appreciation and gratitude. It entails giving to the gods and and expressing gratitude when you receive something from them.

Eusebia - This is the pillar that signifies reverence and veneration towards the gods. It can be translated to 'piety' or 'reverant conduct' meaning that you show respect for them.

Hagneia - This is the pillar that signifies purifying yourself. It entails having moral, perhaps physical too, purity and avoiding miasma where possible.

Arete - This is the pillar that signifies excellence and brilliance. It entails trying to reach your highest potential and this can be in any field.

Sophia - This is the pillar that signifies the pursuit of knowledge and wisdom.

Sophrosyne - This is the pillar that signifies self-control and prudence. It involves being of sound mind and remaining balanced, which can further lead to other positive qualities to have.

I hope these are right and that I didn't misunderstand their meanings! Hopefully this is useful to anyone, I certainly enjoyed making the post!

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Readings to pay for top surgery

I will be offering readings to help fund my top surgery cost! (About $5,000)

What I’m offering

You can choose what deck is used from my collection of 30+

Reading with 1 tarot deck and 1 oracle deck: $10

Add (unlimited) additional decks for $2 each

Add ons:

Pendulum reading: $3

Die casting: $4

Charm casting: $4

Rune casting: $3

Bibliomancy: $5 (different books offered)

Domino casting: $2

Colormancy: $1

And if you’d like I can call in a Greek god of your choosing!

I’m losing my insurance at the end of this month but my top surgery is scheduled for the end of May! Ive been waiting for this surgery for 7 years so I really don’t want to cancel.

If you wanna just donate that’s cool too!

Handles:

C$happ: okaykid4

V**mo: okaykid

Any bit helps!

193 notes

·

View notes

Text

worship evolves with time. yes, the people who worshipped the gods back in the day had specific offerings to be given. but what is stopping you from giving modern offerings? things around your house? offerings shouldn't have to cost you a fortune. your deities aren't holding you at gunpoint to only receive what you can't easily get. they are a means of showing your love in your day-to-day.

so yes!! give your deities candy bars! show them a silly little doodle of them in the corner of your notebook!! make a spotify playlist and play it for them!! dedicate a journal to them!! make a pinterest board and fill it with pins that remind you of them!!

the important aspect of these offerings is that you are thinking about your deities. thinking about them and feeling love and devotion to them is a means of offering! you are devoting your energy in these acts!!

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

If you’re finding it difficult to carve out a practice for yourself, you’re just having a normal response. We were never supposed to do this. Polytheism is not an orthodoxy that we can divert to based on dogma and texts. It’s an orthopraxy, the likes of which were always intended to be practiced by the community, the polis, with the guidance of elders and experts. Because of the march of time bringing forced Christianization, colonization, and capitalism enforcing rugged individualism, we’ve been left with little choice but to carve a tiny piece for ourselves.

We’re doing fantastic, considering we’re rebuilding from the scraps and ruins of long gone empires.

662 notes

·

View notes

Text

🌞O’ Lord Apollon, O’ great god of the Sun, Archery, Music, Art, Poetry and Prophecy. Please take this e-offering 🌞

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

I see Apollo in every sunset, every hue of gold and orange and soft pink, the light casting shadows over the slate-gray clouds. I hear Apollo in every song that gets stuck in my head, every beat that makes me drum my fingers in rhythm. I hear Apollo in every crow's caw, every raven's croak echoing in the trees, every swip of flapping feathered wings. I feel Apollo in every weeping cello note, every sweeping melody in a soundtrack that sends goosebumps along my skin and a rush of emotion into my chest.

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

Apothnesko and the Psychopomp

CW: death, death of sibling, death of parent, death of partner, death of child, illness

Apothnesko awakes to crying. In the dim light of the moon through the window, he makes out the lank childish frame of his older brother Neos sobbing into the arms of a man he’s never seen before. Dressed in the dark garb of a traveler, the man gets to his knees to console the young boy, patting his back and murmuring to him that it is alright to be upset, it is normal. This all is very normal.

Upset to see his brother in such a state, Apothnesko rises to his feet and reaches out to him but his fingers meet cold air where he once would have met warm skin. Horrified, he grabs the post of his bed to steady himself and stares wild eyed at the intruder.

“It is okay,” says the man, “Your brother has died. I’ve come to collect him. He will not be lost.”

“You’ve killed him?” Apothnesko asks, recoiling.

“No, he was ill and his body can no longer house his spirit. I will take him to his new home,” the man clarified, standing up and grabbing a staff carved with twinning snakes he’d leaned upon the wall. He slipped his hand into that of Neos and helped him take a few steps toward the door, never urgent, never impatient. The boy looked to Apothnesko but seemed unable to speak through his grief.

“Wait,” Apothnesko cried, hoping to delay them, desperate for even a moment longer with his brother, “Are you Death?”

The man smiled. “I travel to it often,” he said, gently, “I am it’s familiar friend and servant.”

“Please, tell me sir, how may I live long?” asked Apothnesko.

“I have no way to ensure that,” said the man, motioning to the boy’s brother who was leaning on him as he spoke.

“Then tell me how may I die well?”

The man took the boy’s face in his hand, his own expression soft and deeply, wonderfully kind. “Know that you are very mortal and that very much matters.”

With that, the man turned on the heels of his winged sandals and guided Neos out.

—

Now the sole heir to their family’s small city state, Apothnesko throws himself into his studies. He spends his mornings being trained in several different weapons by his father’s guards. His afternoons are spent deep in discussion with his many tutors on topics of science, strategy, and diplomacy. Every evening is spent with his father Geronto as he tells stories of his many accomplishments and failures. Every moment of his day, he remains committed to learning everything he can. Skill, he thinks must be key to a long and happy life.

One day, an army arrives at the city’s gates. His father and the diplomats dispatch messages to try to negotiate for peace but the army’s leader will not be swayed from taking the city and enslaving it’s citizens. Their defenders ready themselves. Apothnesko, dutiful as ever, is close to his father’s side. He is given command of his own unit of men. Together they descend upon their enemy.

The clash is fierce. Men are struck, some immediately silent and others crying out through the maelstrom of human misery. After the initial clash, Apothnesko regroups his men, finding mounts for them as he is able. He retreats to a hill and commands them to attack the enemy at an angle. Together, they force the attacking lines apart and scatter the remaining army.

As he sees them retreating, he turns to his father to share in this victory but he is no where to be found. Desperately, he searches the field for hours, finally finding his father collapsed in front of the city gate where he fought off a group he’d spotted trying to sneak in. Apothnesko drops to his knees beside him. He scarcely notices a familiar figure in a dark cloak and hat as he approaches and plants his carved staff in the ground beside Geronto.

“It is okay,” says the familiar man, bending to look over Geronto’s body, “Your father has died. I’ve come to collect him. He will not be lost.”

“I have lost him,” Apothnesko says, his head in his hands now, “I am lost without him.”

“The important parts of him are still with you even now,” the man reassures him, taking Geronto’s hand and helping his spirit to his feet.

Seeing the man beginning to take his father from him sends Apothnesko back into his battle rage. He grabs the dagger still strapped to his waist and points it at the cloaked man’s neck.

“Tell me, what right do you have to take this man who has lived so nobly and always for the benefit of others?” said Apothnesko, furious.

“I have no right only a duty,” said the man, smiling gently and motioning to his staff, “Same as you.”

Apothnesko’s shoulders went slack at this. The dagger falls from his limp hand and clatters on the stone pavement below. He looks up and asks, “Then tell me how may I die well?”

The man picks up the dagger and places it back in it’s sheath, his expression soft and deeply, wonderfully kind. “Know that you are very mortal and that very much matters.”

With that, the man turned on the heels of his winged sandals and guided Geronto out.

—

Apothnesko ascends to his father’s throne. He is married to the princess of an allied city state, an arrangement made by his father before his death. The couple are kind to one another and perform their roles well, though there is little real affection between them. Together they rebuild and revive their polis; it’s walls higher and it’s buildings far grander than those in the age of his father. And yet there are still days where his grief pins him to his bed and scarcely lets him leave. No accomplishment, no act of grandeur lifts him.

Desperate to raise his spirits, his wife introduces her husband to a young man named Eros. He is handsome and intelligent but mostly he is kind in a way that reaches Apothnesko in a way his wife’s dutiful assistance cannot. His humor and levity helps the king to feel renewed. Their friendship blossoms into romance and the pair become inseparable. Their days are spent entirely in each other’s company. The young king once again feels purpose and urgency, rising each morning thinking only of what adventure he will embark on with his treasured lover. Love, he thinks, must be key to a long and happy life.

During a great city festival, Eros takes the lead in the great hunt. He is outfitted with the finest gear the polis can offer and he and a company of men set out to bring back that night’s feast. Apothnesko attends to his many ceremonies but always ever has an eye on the gate his lover left through, excited and ready to great him upon his return.

It is close to dusk when the party is spotted, a figure clearly being carried between some of the men. Apothnesko’s heart sinks as they come into view. Eros is limp in the arms of his fellow hunters, bloodied almost beyond recognition. The king rushes to his lover’s side and demands they call the healers. But the hunters insist it is too late, there is nothing left to be done. They withdrawal to let the king mourn.

Night falls and he cannot bring himself to leave Eros, cradling him and stroking his hair. The shadows of the olive trees embracing them both. He feels a warm hand on his shoulder and does not look up.

“It is okay,” says a familiar voice, “Your lover has died. I’ve come to collect him. He will not be lost.”

“I cannot afford to lose him,” says Apothnesko, clutching at his lover’s body, limp but still warm in his arms. “We aren’t done creating the life we promised to each other.”

“Promises are tricky things,” says the Man, taking the hand of Eros and easing his spirit to his feet.

“Tell me, what can I give you to let me keep this man with me even but even for a few hours longer?” pleads Apothnesko, shuffling through his pouches on his waist and drawing out a few gold coins.

“I have no room nor need of gifts,” said the man, smiling gently and motioning to his belt, clearly bereft of pouches.

Apothnesko nods, the gold spilling from his hand and onto the ground. Tears stream down his face as he asks, “Then tell me how may I die well?”

“Know that you are very mortal and that very much matters.”

With that, the man turned on the heels of his winged sandals and guided Eros out.

—

Apothnesko does not leave his room for many weeks. No one can get him to come from his bed chamber and the servants notice he is eating very little of the meals they bring him. His wife and the family of Eros both beg him to return to his duties but he refuses. There is worry despair might claim him.

That is until he hears a child’s cry in the palace. His wife has given birth to a son. He rushes to be by her side and smiles for the first time in months when handled the infant child. At last an heir, a child to secure their many advancements and bring up in the ways his father brought him. His son can carry their traditions on so that they far out live any one of them. Legacy, he thinks, must be key to a long and happy life.

The physician returns to the couple with a worried look. He explains the child appears to be sick and he is unsure how long they may have with him. Apothnesko’s wife clutches the child to her and refuses to let it from her sight. That night they all sleep together, the child asleep on his mother’s chest while Apothnesko kept watch.

Deep in the night, he hears a man with a walking staff enter the room and looks up. The man smiles softly from across the room, walking slowly to toward the bed. His dark hat and cloak the same as ever.

“It is okay,” says the familiar man, “Your son has died. I’ve come to collect him. He will not be lost.”

“If you take him from me I will have lost everything. There is no life without him, no polis, no hope,” he says, his voice flat.

“Everything that is done must be undone,” says the man, nodding solemnly.

“Then what is the point of doing anything?” asks the king, numb, “If everything comes to ruin, why do anything, love anything at all?”

“Doing nothing won’t prevent this,” says the man, cradling the child tenderly, “Doing something won’t either. But the story you tell is up to you.”

“Then tell me how to bring about a good ending,” says Apothnesko, “Tell me how may I die well?”

The man smiles knowingly, his face soft and deeply, wonderfully kind. “Know that you are very mortal and that very much matters.”

With that, the man turned on the heels of his winged sandals and guided the child out.

—

Apothnesko and his wife grieve their child. She decides she cannot have another and they select the king’s nephew as heir. At first, Apothnesko is nervous to teach the boy, knowing that at any moment the strange traveler may come to collect him. But he thinks of his father, he is generous with his knowledge, teaching him all he knows. When he thinks of his lover, he delights in sharing joy with the boy. When reminded of his son, he tells him stories to pass on.

Together, they see their city through many bountiful and troubled times. When a crop is particularly abundant, they celebrate with a festival for the entire city. When they hear of those who’ve lost their loved ones, they go to them and grieve as if their sorrow were their own.

As the boy approaches adulthood, Apothnesko begins to grow weary. His strength begins to leave him and he give more and more of his duties to his heir. One day, he grows ill and takes to his bed. The city is saddened by this news. Many send word of their love and admiration for the king that not only saved them but lived alongside them. His nephew goes to keep watch over him through the nights, determined he will not pass alone.

It’s the early hours of one morning that Apothnesko feels a hand on his shoulder, waking him with a start.

“It is okay,” says the familiar voice, “You have died. I’ve come to collect you. You will not be lost.”

“At last,” says the old king’s spirit, smiling, “Friend of my friends, loved of my beloveds - how great to see you again.”

His spirit rises up to greet the man and takes his hand. His nephew smiles, recognizing the man from the kings many stories.

“You saved our city and survived great loss,” says his nephew, “You rebuilt our home and united our people. Before you leave, please tell me what allowed you to live such a great life?”

Apothnesko turns to his nephew, his expression soft and deeply wonderfully kind. “Know that you are very mortal and that very much matters.”

With that, Apothnesko turned on his heel followed his old friend out.

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dear fellow pagans:

Take your Greek mythology with a grain of salt.

The ancient Greek writers were horribly misogynistic, and they never missed an opportunity to make the Goddess or woman out to be evil or sneaky. Note anything by Hesiod alone. They even turned Gaia, the literal earth and mother of creation itself, into a cruel and rebellious bitch. Athena punished a rape victim and then aided her assailants for fun. Aphrodite was vain and selfish. The entire story of Persephone.

I'm not saying ignore the past, what I'm saying is if you want to work with these Goddesses, you don't have to stick to the ancient script created by men who hated them. You can, in fact, modernize and worship in how you connect personally. Religion should be about having fun.

624 notes

·

View notes

Note

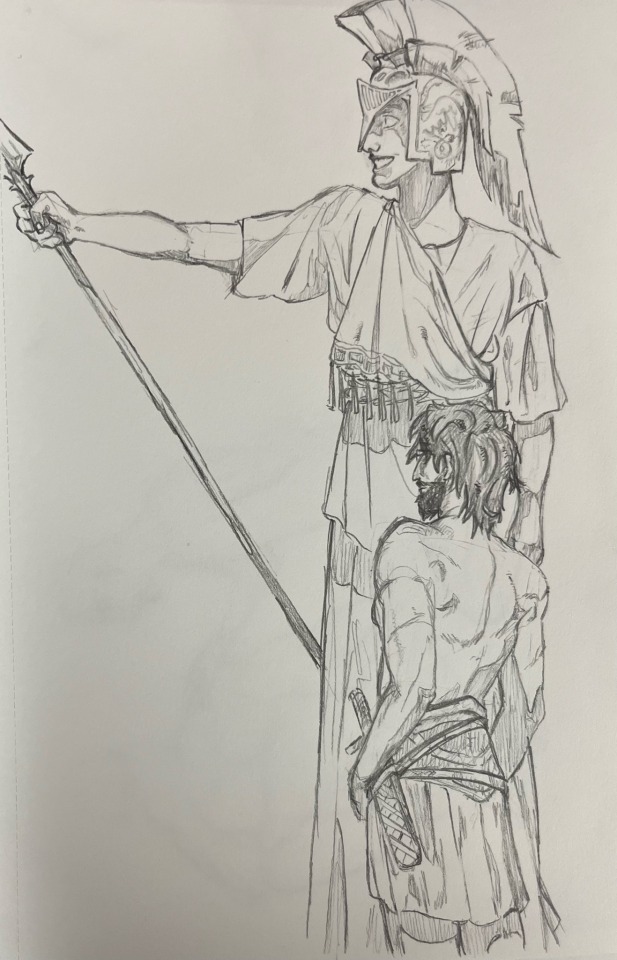

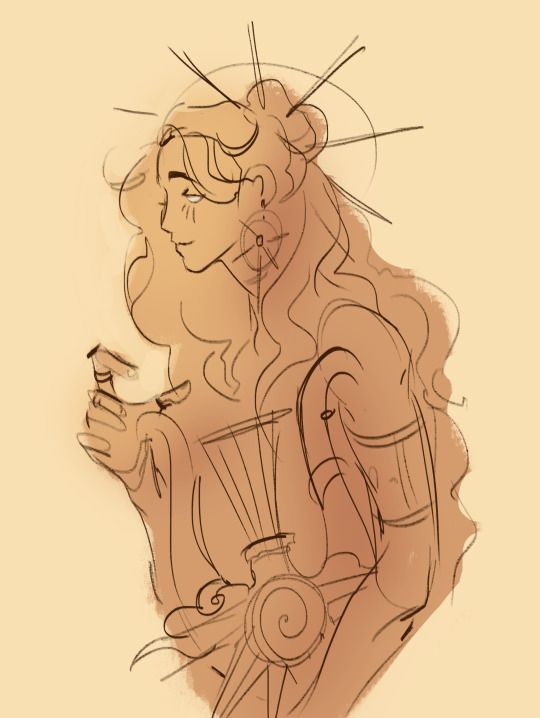

yo could I get a lil apollo doodle for my friend’s birthday? she’s an apollo kiddo and I wanna give her something special :)) /nf

ye

779 notes

·

View notes

Text

good morning and happy sunday, lord apollon,

protector of the young and god of plague.

thank you for the light that shines through my window,

i call this prayer to honor you and express my admiration.

bright shining apollon, hear my words and please enjoy the offerings i give you throughout the day.

it will be as you allow it 💛

476 notes

·

View notes

Text

Remember,

You are a practicing pagan. You don't have to do spell work everyday. You don't have to talk to your deities everyday. You don't have to spend every waking second focusing on your practice to be a valid pagan.

Your valid. No matter how often you're able to work with your deities. No matter how often you do spell work. No matter if you dedicate little or big things to your practice.

You make an effort once in awhile and thats more than enough. Save your spoons, it's ok.

741 notes

·

View notes