Link

“/.../ many people within and outside of the radical left began to see that debt was not always legitimate, but that it was being used maliciously around the world to centralize power and money. For many, like me, an understanding of how common, how big and how predatory debt systems were allowed us to feel like we weren’t individual brutal failures. Overcoming this isolation has fuelled activists to form important anti-debt movements /.../. And yet in spite of these movements, it remains the case on our poor planet that debt, like illness, is still usually seen as a fate to be suffered in terrified isolation. In a bio-medicalized capitalist world, we are trained to see our illness separately from the society of toxins and stresses. At the same time, it also leads us to see our debts as personal liabilities rather than as the result of a sick society.

*

In the depths of space, debt appears simply as obligation, reciprocity or bonding. When does it turn into the toxic and coercive form that reproduces human hierarchies? What could debt be, if it wasn’t used by the powerful to control/ contaminate reality with the disease of hierarchy, to create a world where a few people thrive (materially) while most people suffer? What could debt enable if it wasn’t just a tool by which some (mostly white male) humans accumulate so much labour and resources that they could shoot themselves into space? What would it look like to harvest a form of debt that produces health and interdependence on earth? What if we didn’t feel like a burden on each other, for needing each other in harsh conditions?”

0 notes

Text

I Want a Wife

by Judy Brady

1- I belong to that classification of people known as wives. I am A Wife. And, not altogether incidentally, I am a mother.

2- Not too long ago a male friend of mine appeared on the scene fresh from a recent divorce. He had one child, who is, of course, with his ex-wife. He is looking for another wife. As I thought about him while I was ironing one evening, it suddenly occurred to me that I, too, would like to have a wife. Why do I want a wife?

3- I want a wife who will work and send me to school. And while I am going to school, I want a wife to take care of my children. /.../

4- I want a wife who will take care of my physical needs. /.../

5- I want a wife who will not bother me with rambling complaints about a wife's duties. /.../

6- I want a wife who will take care of the details of my social life. /.../

7- I want a wife who is sensitive to my sexual needs, a wife who makes love passionately and eagerly when I feel like it, a wife who makes sure that I am satisfied. /.../

8- If, by chance, I find another person more suitable as a wife than the wife I already have, I want the liberty to replace my present wife with another one. Naturally, I will expect a fresh, new life; my wife will take the children and be solely responsible for them so that I am left free.

9- When I am through with school and have a job, I want my wife to quit working and remain at home so that my wife can more fully and completely take care of a wife's duties.

10- My God, who wouldn't want a wife?

Fulltext: http://www.columbia.edu/~sss31/rainbow/wife.html

0 notes

Video

youtube

Who Cares? is a brand new series which sees comedian and Chicken Shop Date creator, Amelia Dimoldenberg take to the streets and vox pop the UK public on the burning issue of the day in her signature comedic style.

0 notes

Link

The normalizing of Indigenous knowledge and science is a core aspect of Indigenous futurism literature and art. Indigenous knowledge systems are often thought of as primitive or illegitimate, so situating them in speculative worlds allows Indigenous futurists to assert those systems’ strength and perseverance.

“Whenever we try to envision a world without war, without violence, without prisons, without capitalism, we are engaging in speculative fiction,” writes Walidah Imarisha /.../ “All organizing is science fiction.”

When water protectors gathered at the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation in 2016 to oppose the construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline, the economic and social system the protectors developed to sustain the camps was a form of resistance. While fighting against pipeline development on tribal lands, water protectors also created, sustained, and funded the camps through a radical mutual-aid system.

The camp offered an anticapitalist, anticolonial model for community organizing and community building, one built not on competition or meritocracy but on the centering of Indigenous values. In many ways, Standing Rock was a microcosm of speculative fiction. More recently, at protests against the building of the Thirty Meter Telescope at the top of Mauna Kea—an ecologically sensitive and sacred Indigenous land—Native Hawaiians have created independent systems of support. Kaniela Ing, a Native Hawaiian and former member of the Hawaii House of Representatives, tweeted: “11 days in, Hawaiians have established: Free Healthcare [Mauna Medics], Free College [Pu’uhuluhulu University], Free Childcare [Kapunana] / 241 years in, America still no can.”

Science fiction itself may not change colonial policies, but it challenges us to think beyond oppressive, normative structures and histories. Unfortunately, the mainstream genre continues to be dominated by white people.

0 notes

Link

Kanada kirjandusteadlane Chris Ferns on eristanud kahte tüüpi utoopiat: unistused korrast ja unistused vabadusest ning väitnud, et suurema osa korrast unistavaid utoopiaid on kirjutanud mehed, samas kui vabadusest unistavate utoopiate autoriteks on vähemalt 20. sajandist alates olnud valdavalt naised. Korda loovad utoopiad, nagu More’i oma, on valdavalt naisi ja nende vabadusi piiranud ning naissoost autorid on taas püüdnud neid piire laiemaks mõelda.

0 notes

Photo

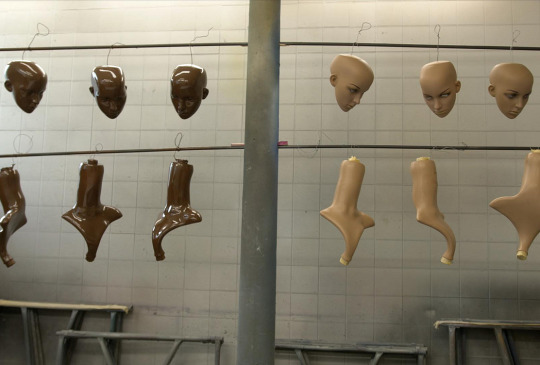

Between These Folded Walls, Utopia by Cooper & Gorfer

Over the past 14 years, Cooper & Gorfer have traveled to Argentina, Iceland, Kyrgyzstan, and Qatar, among others, to work with women from various cultures exploring issues of memory, feminism, migration, dislocation and the malleability of identity. Intrigued by the notion that today’s world is in a state of lost utopia, the artists began to dig deeper into the meaning of utopia, triggering a three-year collaboration with young women from their local communities in Sweden.

The young women featured in the series are all between the ages of 17 and 24 and have been touched by forced migration in one way or another. Many of them came as refugees with the last migration wave in 2015, whereas others are second generation, born in Sweden to expat parents.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

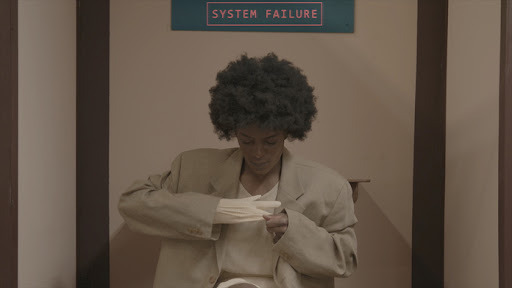

Silvia Martes’ film The Revolutions That Did (Not) Happen

De Pont Museum: "The film takes place in the year 2085. She suggests an age in which political and social structures have collapsed as a result of wars, pandemics and natural disasters. The new society to be developed is one of equality, one where women of color – in line with the artist’s own skin color – work in all levels of its hierarchy. But it is also one that bears an unpleasant number of similarities to a totalitarian state: here everyone has swapped their identities for grey suits, and people cannot be distinguished from robots. Martes has taken inspiration from the way in which, through the influence of the Internet and social media, we have all begun to resemble each other, while – paradoxically enough – individuality is rewarded. The film is thus full of ambiguities about the necessity and meaning of change, mass behavior, individuality and the cost of the work ethic. Matters that continue to occupy us even after the film is over. By fantasizing about the future, Martes exposes above all the shortcomings of the present.”

0 notes

Link

In this moment of environmental breakdown, a global pandemic, and economic crisis, we need utopian and radical visions of society more than ever. This is not escapist wishful thinking but a reimagining of society as one that values people over profits, that rules democratically and collectively, and that provides for the needs of all.

The following books question what our future might look like, offering utopian thinking that can inform our social movements today.

0 notes

Link

The richest 1% of the world’s people (those earning more than $172,000 a year) produce 15% of the world’s carbon emissions: twice the combined impact of the poorest 50%.

A recent analysis of the lifestyles of 20 billionaires found that each produced an average of over 8,000 tonnes of carbon dioxide: 3,500 times their fair share in a world committed to no more than 1.5C of heating. The major causes are their jets and yachts. A superyacht alone, kept on permanent standby, as some billionaires’ boats are, generates around 7,000 tonnes of CO2 a year.

...But their carbon greed knows no limits: some of the super-rich now hope to travel into space, which means that they would each produce as much carbon dioxide in 10 minutes as 30 average humans emit in a year. The very rich claim to be wealth creators. But in ecological terms, they do not create wealth. They take it from everyone else.

There’s an oft-quoted axiom, whose authorship is obscure: it is easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism. Part of the reason is that capitalism itself is difficult to imagine. Most people struggle to define it, and its champions have generally succeeded in disguising its true nature. So let’s begin by imagining something that’s easier to comprehend: the end of concentrated wealth. Our survival depends on it.

0 notes

Link

Winning the National Book Foundation medal for distinguished contribution to American letters in 2014, the late Ursula K Le Guin spoke of how how “hard times are coming, when we’ll be wanting the voices of writers who can see alternatives to how we live now, can see through our fear-stricken society and its obsessive technologies to other ways of being, and even imagine real grounds for hope”. Seven years later, a new literary award is being launched by her estate to honour those authors.

0 notes

Link

“So, is there energy enough for all? Yes. Is there food enough for all? Yes. Is there housing enough for all? There could be, there is no real problem there. Same for clothing. Is there health care enough for all? Not yet, but there could be; it’s a matter of training people and making small technological objects, there is no planetary constraint on that one. Same with education. So all the necessities for a good life are abundant enough that everyone alive could have them. Food, water, shelter, clothing, health care, education.

If one percent of the humans alive controlled everyone’s work, and took far more than their share of the benefits of that work, while also blocking the project of equality and sustainability however they could, that project would become more difficult. This would go without saying, except that it needs saying.

To be clear, concluding in brief: there is enough for all. So there should be no more people living in poverty. And there should be no more billionaires. Enough should be a human right, a floor below which no one can fall; also a ceiling above which no one can rise. Enough is a good as a feast— or better.”

0 notes

Link

Here’s one thing I’ve been saying to open eyes around geoengineering: women’s rights are a geoengineering technology. Here’s why: when women have developed and achieved rights, because we need to get to post-patriarchy as well as post-capitalism, the population replacement rate — a steady population is like 2.1 kids per woman — drops naturally from their own life choices to a rate of like 1.8 or 1.6. So, if you start talking about women’s rights as a geoengineering method, that takes it out of the techno-silver-bullet land, which is where we’re stuck right now.

So law, justice, post-capitalism, women’s rights, post-patriarchy — all these things could be defined as forms of geoengineering, and at that point, the term kind of falls apart. What we’re really talking about is civilization, as such, as a form of biosphere management.

0 notes

Link

We understand co-authorship as a critical attitude towards current competitive structures within the art world which prioritize the visibility of individual names and success. We believe it is urgent to build platforms of collaboration that promote generosity, co-learning, sharing, and experimentation.

Multi-vocality relates to what can emerge when we respect the multiplicity of experiences. Encouraging numerous articulations (of experience) requires making space for difference. This is one of the ways we hope to practice feminism. Sharing intimacies, or making private life public, was crucial to us.

Several members of the group are caregivers while maintaining part-time and full-time jobs. In each of the places we come from, society continues to expect women to engage in reproductive labor, while the stigmatization of that labor persists. By consciously bringing our voices together, we are adding to rich histories of female labor and women working collectively. This is important, as not only does it build a sense of solidarity between ourselves, but also—we hope—makes space for other voices with a diversity of lived experiences and knowledge to join this conversation too.

0 notes

Video

vimeo

Humans dominate the planet. As a consequence of hundreds of years of colonisation, globalisation and never-ending economic extraction and expansionism we have remade the world from the scale of the cell to the tectonic plate. But what if we radically reversed this planetary sprawl? What if we reached a global consensus to retreat from our vast network of cities and entangled supply chains into one hyper-dense metropolis housing the entire population of the earth?

Planet City, by Los Angeles-based film director and architect Liam Young, explores the productive potential of extreme densification, where 10 billion people surrender the rest of the planet to a global wilderness. Although wildly provocative, Planet City eschews the techno-utopian fantasy of designing a new world order. This is not a neo-colonial masterplan to be imposed from a singular seat of power. It is a work of critical architecture – a speculative fiction grounded in statistical analysis, research and traditional knowledge.

0 notes

Video

vimeo

Miki Kashtan:

“Exchange means it goes back and forth instead of flowing all around. And there can be more exchange or less exchange, it’s not a binary thing that you’re either exchanging or gifting. There can be more or less uncoupling of giving from receiving. For example I have a naturopath that I’m working with. /.../ I’m going to give you a fixed amount of money every month regardless of how many sessions we do or don’t schedule. /.../ So that is still exchange because I am giving her money in relation to a service that she’s giving me but it is far less exchange and much more of a kind of turn-taking fluid thing because of the fact that it is not tied directly to what and when she’s giving me.”

“There is an ethos of sacrifice within a lot of activist communities that I don’t believe will create a world that works for all. It’s an ethos of service where honouring my needs is not separating myself. To think of it as separating myself is still within the consciousness of either/or. It’s I care for my needs or I care for your needs. When in reality when we are in community, we create flow and by ourselves we can never create flow.”

0 notes

Link

Design fictions are a mix of science, design and fiction. The term describes an emerging area of design that uses storytelling as an experimental device to question the world around us. Using a combination of concepts, objects and visuals, design fictions are propositions for how things could be done differently. Depending on the viewer’s perspective, these fictions can be understood as anything from a cautionary tale to a Utopian ideal.

London based designers Dunne & Raby have been working with what they refer to as Critical Design, Speculative Design and thought experiments for many years. Combining elements of industrial design, architecture, anthropology, science and sociology they stimulate discussion and debate about the social, cultural and ethical implications of existing and emerging technologies.

0 notes