Photo

Historical Chocolate Recipe

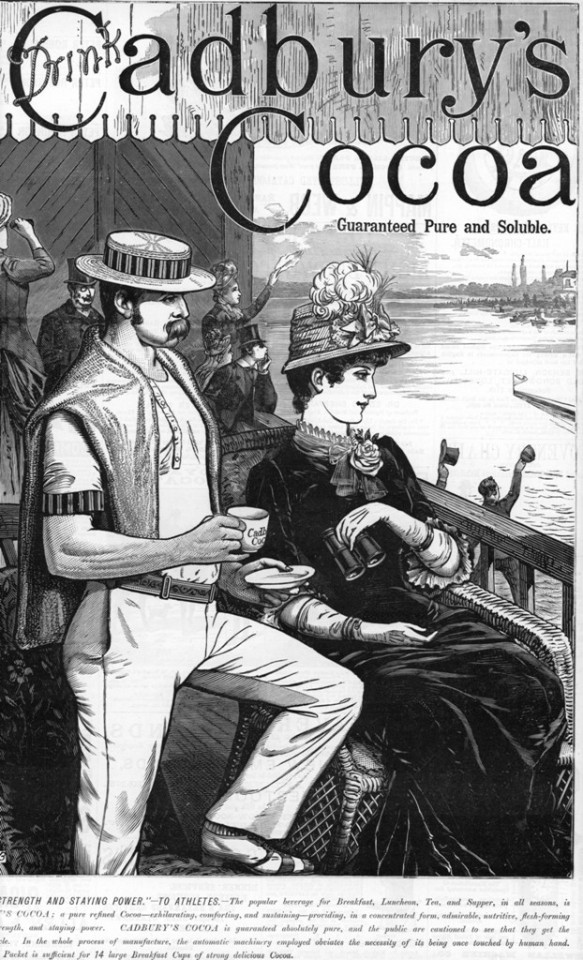

Christopher Columbus set out on 11th May 1502 on the fourth and final voyage to explore the world. He had four ships and wanted to explore areas in the Caribbean to find a passage to the Orient. He was offered cacao beans on the last voyage and failed to accept or taste the drink made from a recipe. It meant missing the opportunity to introduce cacao to the Old World. However, in 1528, Hernan Cortes was a Spanish conquistador who exported cocoa beans to Spain (Predan, Lazăr, & Lungu, 2019). The importance of this document is to present the history of chocolate through a recipe in Spain. It will identify a historical recipe using cacao or chocolate as the main ingredient. It will give the origin of the recipe, the time it was created, the socio-economic context of individuals preparing and creating the recipe, and the cooking techniques used. It will then give additional ingredients used in the recipe, religions who rejected or adopted the recipe, and how it was disseminated. Any cook trying the Chocolate a la Taza recipe will determine how Christopher Columbus missed an opportunity to introduce cacao beans to Europe.

Conquistadors exported cacao beans to Spain where monks would process them. They began to adjust the drink to have a Spanish taste by adding cane sugar, nutmeg, and cinnamon but omitting chili. They started serving the drink hot. The recipe is served with a glass of water, a custom Spanish drink from the 18th century. Cinnamon is not a Mexican hot chocolate recipe but a Spanish one. It is currently considered a Mexican drink in contemporary cuisine (Santaliestra, 2018). However, it arrived in the country in the mid-16th century when Spain began to amass colonies in the Philippine islands. It began to grow in Spain eight hundred years after the Spanish had introduced it. North African tribes had invaded the area, which led to its growth.

Chocolate a la Taza recipe serves four groups. Monks required many suitable gratings of nutmeg, one small cinnamon stick, two cups of water, and ¼ a cup and two tablespoonfuls of sugar. They also needed 4 ounces of unsweetened baking chocolate that had to be broken down into chunks. The baking chocolate bar had to be 100% cacao without additional oil or sugar. Preparing the recipe is to combine sugar, chocolate, and water in a large pot placed over medium heat. Whisking then follows until the dissolution of the chocolate. Nutmeg and cinnamon are added, and the mixture is cooked over medium to high heat with constant whisking until the entire mixture begins bubbling. The heat is reduced, and the mixture continues to cook for around two minutes with whisking until it has thickened (Arendt & Dal Bello, 2016). The drink needs to be served warm.

The Catholic Church considered that native chocolate was less of a nourishing drink than a connotation to pagans found in North America. Spanish conquistadors drunk native chocolate two times every day to get energy on any expedition they needed. They had adopted chocolate from the Aztecs in Mexico as a beverage made from cacao. The initial chocolate was the use of cacao rather than a thick solid rectangle divided into ounces. The Aztecs fermented the drink and used it like beer or wine. It then became a drink with spices, water, and cacao. However, the native drink, which was sour and spicy, was considered a juice. Condiments like chili and spicy pepper were added, and it contained a large amount of water. The drink that the Spanish conquistadors were taking in the 16th century reached Spain. They replaced water with vanilla, added sugar, and milk instead of spicy pepper (Schermers & Blokker, 2018). They called it chocolate, and it remained a drink. The Catholic church thought that the drink would break the fasting ritual before attending mass, which implied that it was banned when an individual was expected to attend church the same day.

The church had failed at stopping people from consuming the drink because it had become part of Spain. Individuals drunk chocolate all the time while religious and noble people did likewise in secret. It became a taboo to drink chocolate, but this move increased the excitement and attraction to the product because of the link with sexual intercourse. The stigma that had been acquired in the country spread across Europe. Nobles and Spanish Catholic church orders helped spread the drink to foreign acquaintances. Nobles and Spanish royals took chocolate with them to every European Court that they attended. They bought it as the new product from the Americas and Spain, and it became popular among the upper class within Europe. It became a luxury during the Industrial Revolution and acquired refinement connotation (Santaliestra, 2018). This resulted in developing other chocolate recipes with several additives, changed concentrations, solids, and shapes. However, the traditional way of consuming chocolate remained the Spanish way, which was a thick drink.

Spanish conquistadors had kept their distance from chocolate. They saw that it stained the lips with blood after an individual consumed the drink. It was seen as a drink for pigs rather than humans. However, the return of Hernan Cortes to Spain from conquest in 1521 in Mexico changed the history of chocolate. He presented a drink of the Aztecs made from cacao beans to King Charles V. The recipe did the addition of sugar to make chocolate popular among nobles in Spain (Santaliestra, 2018). Chocolate was first prepared in the Cistercian monastery of Piedra. Monasteries became significant consumers of chocolate, and they bought the drink in mass. While not all religious orders approved of the drink, it became a favorite among monks. Jesuits rejected the drink because it was a precept to motorway poverty and the flesh. However, this did not stop various individuals from consuming the drink. Spanish monks began adding spices and sugar to make the drink hot and sweet. It then led to chocolate's popularity, with the Spanish secretly producing chocolate and controlling the import of cacao beans from the Americas. The drink became part of Europe's upper class for the next 200 years, and candy and chocolate bars were developed in the 19th and 20th centuries. The Spanish remain to love the drink, and it is common to find children drinking chocolate for breakfast. The drink is also typical in various areas around the world.

In conclusion, Christopher Columbus missed the opportunity to introduce cocoa into the Old World. Then, The Catholic Church considered that native chocolate was less of a nourishing drink than a connotation to pagans found in North America. However, monks secretly drank it and prepared the Chocolate a la Taza recipe by adding spices and sugar to make the drink hot and sweet. It then led to the popularity of chocolate in Spain and the entire world.

References

Arendt, E., & Dal Bello, F. (2016). Science of Gluten-Free Foods and Beverages. Academic Press.

Predan, G. M. I., Lazăr, D. A., & Lungu, I. I. (2019). Cocoa Industry—From Plant Cultivation to Cocoa Drinks Production. In Caffeinated and Cocoa Based Beverages (pp. 489-507). Woodhead Publishing.

Santaliestra, L. O. (2018). “Dinners, Sorrows and Suns Kill Men”: Preventive Medicine of an Ambassador who Survived to his Embassy (1663-1674). Chronica Nova, 44, 147-175.

Schermers, H. G., & Blokker, N. M. (2018). Legal Order. In International Institutional Law (pp. 751-870). Brill Nijhoff.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Chocolate Futures: Fair Trade and Sustainability

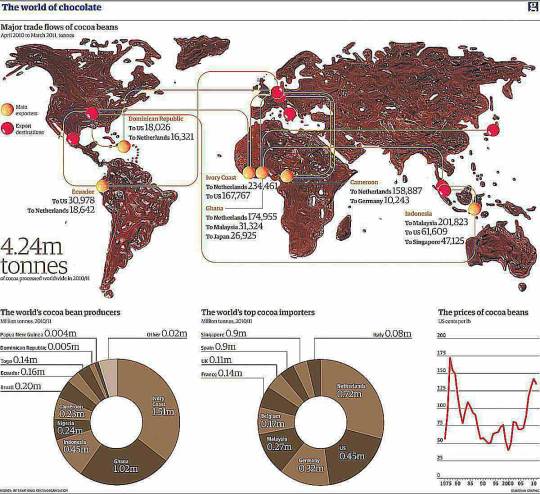

If globalization is anything to go by, then it lies in all individuals' roles in the cocoa supply chain. A shopper in New York may feel he or she is more important than the producer in Tanzania, Papua New Guinea, or Brazil. The moniker of being at the end of the supply chain is inadequate to discount the origin of the chain itself. A globalized world needs to acknowledge equality and understand the plight of individuals at the lowest end of the supply chain. These have a role to play in the contemporary community and no less as cocoa farmers. The introduction of fair trade has offered such individuals with the protection they need to succeed. It is of utmost importance that society protects its residents against unwanted exploitation. Producers need to ensure that they follow the highest standards of production. Then, factories need to uphold similar standards to ensure that they get the right product and in the best condition possible (Kristy). However, it should not imply that clients mean everything in the market. Organizations must understand that all aspects of the supply chain need to run in unison. The failure to allow all elements of the demand and supply of cocoa and chocolate may jeopardize. Companies that have realized this aspect of their businesses already know that the only way they can succeed is to meet both sides' demands. Thus, they are impartial, which goes a long way in enabling them to succeed in the cocoa and chocolate business.

Ryan (2011) contends that fair trade is a crucial aspect of sustainability in businesses. The author states that Chris Martin is not known for his love of chocolate. However, he visited Divine Chocolate in Ghana, which depicted support for the movement. As noted, Divine Chocolate depicts ads of women from an opulent background. They have refused to accept that the African is a debased being. Instead, they have decided to promote Africanism from a perspective never seen before: Western cannibalization. Ryan (2011) wants fair grade to be present, and the reference to Divine Chocolate is a depiction of one of the best companies in the UK that follow the tenet. It would be an understatement to deduce the success that has been realized due to the organization’s efforts. However, what remains questionable is the depiction of women in company ads, as if they are coffee, but then this does not depict their plight, except for usable items.

A government that wants to remain in power needs to take care of small scale farmers' needs. While this may not be apparent in the outset, a factory backlash might present an instance to contemplate actions committed and decisions made in the past. The indispensable nature of the farmer is in itself, unchallenged and incorrigible. The status that this individual occupies threatens the customer. If a farmer decides not to plant, then where the product will originate is rhetoric that companies face when dealing with farmers and clients. Thus, the definitive objective is to protect the farmer under all costs by establishing the right market prices for products.

References

Kristy Leissle, Cocoa, ch.6- 8

Orla Ryan, Chocolate Nations, ch.6.

0 notes

Photo

Chocolate in Modern Times: Expansion of Consumption and New Social Identity

Leissle (2012), states that, the African continent is a depiction of primitivity and traditional lifestyles; rather than civilization and modernization. Even in the chocolate industry, most people expect that the situation should be the same as in Southeast Asia, where exploitation occurs. However, Divine Chocolate advertisements in Ghana show that women have embraced a glamorous lifestyle in Africa. They have forgotten their morals and traditional lifestyle and embraced that of the West. The images depicted show that these women are owners of chocolate factories and cocoa farms. The implication is that they have people working under them.

Consequently, they become beneficiaries of the industry that is expected to oppress them. It is not uncommon to find women taking ownership in such industries because of the need to take advantage of capitalism. The advertisements attempt to bridge the divide between consumers and producers of cocoa. However, this is far from the truth since the poor farmers will continue being oppressed.

Virginia Westbrook discusses the late nineteenth century and the chocolate trade that thrived during that time. Advertisements had become the norm with a capitalistic mindset taking center-stage. Companies had to learn to fight in the market or face extinction. Chocolate corporations took a peek at the market and discovered they could use children's status to achieve their goals. Consequently, they used young people sipping cocoa, strolling siblings, and crawling babies in their ads. On occasion, a doll or of pet accompanied them. It was only a single company that had an eagle's image carrying a box of cocoa and Uncle Sam beside it. Some companies even went the extra mile of using exotically dressed women in their ads. Dutch companies sought to change American history by introducing chromo trade cards. Unsurprisingly, given used aggressive marketing incentives, they managed to propel these companies to the American chocolate market's helm.

Nicholas Westbrook outlines the history of chocolate between 1851 and 1964. At an 1876 exhibition in America, chocolate manufacturers ensured the audience would see their dark-brown displays that mirrored the chocolate they were selling in the country. Chocolate manufacturers realized that they could expand their business if they offered samples for tasting. They even introduced an automatic chocolate dispenser that would pour cups of cocoa sold for five cents. It was also a moment to introduce new cocoa products in the world market. At one time at Niederwald, Stollweck reproduced the Germania. Organizations even represented fantasies in architecture. The goal was to ensure that they would tie down clients to a memorable experience at one exhibition. Clients who remembered these moments would easily purchase from the organizations that were advertising them. At the very least, they would buy from an opponent. Despite this being the case in some instances, they would still help increase the number of sales all over the world. With this in mind, these companies sought to conquer the world as they knew it with innovative chocolate and related products. This would prove useful years later because they reaped the benefits of ensuring compliance with their service delivery standards.

References

Leissle, K. (2012). Cosmopolitan Cocoa Farmers: Refreshing Africa in Divine Chocolate Investments. JSTOR, 121-139.

Westbrook, N. (2009). Chocolate at the world's Fairs 1851-164. In Chocolate: Hsitroy, Culture and Heritage (pp. 199-207).

Westbrook, V. (2009). Root of Trade Cards in Marketing Chocolate During the Late 19th Century . In Chocolate: History,culture and Heritage (pp. 183-170).

0 notes

Photo

Chocolate in Modern Times: Globalization of production

Henderson (1997) argues that the cocoa trade would have thrived in the world if there was no First World War. Liberal forces in Ecuador dedicated their time to modernize the country's existing frameworks of politics, social understanding, and the economy. The country would become a modern economy if it relied on the money gained from the cocoa trade. However, it did not take long, and after two decades into the 20th century, the First World war took a toll on their efforts. The military overthrew them in 1925 because they faced opposition from a domestic viewpoint and were indebted to banking institutions in the country. The paradigm shift in power and economic prowess implied ushering a country into an era of prosperity. Cocoa appeared to be the only hope that would ensure the country scaled the world’s economic ladder.

According to Emma Robertson (2009), capitalism's primary role was to accumulate wealth other than making sure there was economic prosperity for all members of society. Commercial agriculture has been reserved for men in the modern era, and women have had to be relegated to the subsistence sector. It shows a lack of respect for women and a dilution of gender relations in the cocoa farming industry. Pawning was common during the globalization of cocoa farming. An individual who wanted a loan to purchase cocoa trees would send family members to work in the fields. As is the case with many labor-intensive industries like sweatshops in Southeast Asia, cocoa farming came under scrutiny concerning labor laws. Child labor had been deployed as recently as 2001. An incident involving a ship this time for Benin from Nigeria was carrying slaves. The Ivory Coast government and human rights organizations lobbied against chocolate slavery in West Africa. They believed that individuals who labored on cocoa farms had to be treated as equals to all other community members.

The cocoa of the 19th century was viewed as an alcoholic drink. It was a better alternative to the alcohol that the Quakers were still selling during that time. Its arrival in Britain and other European countries underscored its medicinal value. The Quakers played a crucial role in capitalism that helped the spread of cocoa and chocolate in Europe. Their financial muscles made it possible to exploit the market to their advantage and then show that they made a profit. Cadbury began advertising chocolate as the absolute best after securing one of the best chocolate and cocoa making machines. The product was similar to that found in the market, but the organization had discovered that marketing was a critical aspect of capitalism. It made investments in marketing incentives to increase its value in the market and brand appeal. It was not long before other organizations discovered the same formula and began to venture into the market (Off, 2006). However, Cadbury’s still stood out in the market because it had clever packaging to ensure that it would increase its sales volume. This meant that the company was able to maintain its market position.

References

Henderson, P. (1997). Cocoa, Finance and the State in Ecuador, 1895-1925. JSTOR, 169-186.

Off, C. (2006). Bitter Chocolate(The New Press,2006). In C. Off, Cocoa on Trial .

Robertson, E. (2009). Chocolate, Women and Empire.

0 notes

Photo

Chocolate Factory: Technological Revolution

People across the world love chocolate, but very few people know how it came into existence. Ghirardelli is the second oldest chocolate producing company, only Baker’s chocolate company is older than Ghirardelli. Ghirardelli was founded in 1852, considered as one of the wealthiest Italy-American citizen, he launched his company as a manufactory and sales shop in Portsmouth Square. According to (Lawrence, 2002), the company combined the sale of chocolate and candy with liquors as its sole function. It was during the post-civil war years that made San Francisco a business hub where different businesses thrived but he had no competitor in the chocolate business. As a result of the favorable prevailing business conditions in San Francisco, the company grew and expanded its business operations.

In the 1920s, with increased demand for advertising and a strong economy, the company was able to appeal its presence to children through its brand’s sweet taste. For most people across the world, what was called chocolate was actually, a beverage made from coarsely ground cocoa beans obtained from the cacao tree. According (Brenner, 1999), by the time of Christ, the cacao tree had already reached the Aztec civilization in Mexico, where it was believed to be as a divinely inspired gift. The Aztecs community considered it a special plant and as valuable as silver. In essence, the demand and the need for tastes and better quality of chocolates led to innovation.

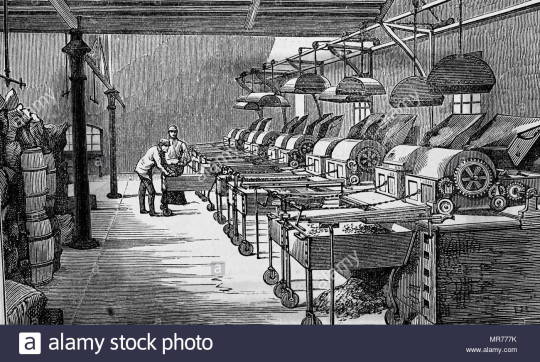

According to (Snyder, Olsen, & Brindle, 2009), the production of chocolate involved grinding roasted beans on a stone slabs surface known as metates where the resulting output would be a solid mass formed into small cakes and tables called chocolate. The ancient manufacturing process resulted in a chocolate that had different flavor and quality features. Therefore, it was completely important to find new ways to produce chocolate that suited different tastes and preferences. The Aztec method of chocolate production started with collecting the beans from the farm and sorting them through the sieving method that would then remove dirt, stones etc. The beans then would be subjected over smokeless fire and stirred as the heat dried the beans.

During the process, the bean shells would be loosened. The warm beans would be cracked by an iron roller to loosen the shells. It was important not to under-roast the beans since they would produce a bitter flavor. The roasted beans would be placed in a mortar and ground into coarse liquor which would be ground further with an iron roller with wooden handles. During that time, there was a need to develop mills which would help in the grinding process. However, it is not clear what powered the mills; water or human labor. The hot paste would then be poured into molds, allowing them to cool down. Different ingredients such as sugar, cinnamon and vanilla would be added to form chocolate pastes or bars.

Across Europe, the Aztec production process was used and only a few changes such as heating the beans to extremely high temperatures. The milling process was the most labor intensive process, therefore it was important to find new ways of improving the process. Milling equipment was necessary to enhance commercial production of the chocolate. It was therefore important to research how to improve the milling process and improve production for commercial purposes. The demand for the chocolate was growing and therefore, the manufacturers had the reason to improve their production. In 1729, Walter Churchman started an improved manufacturing process where he built a water engine to power his stone mills. With the increase in demand, different production lines had to envision how to make quality chocolate and at the same time minimize production costs (Snyder, Olsen, & Brindle, 2009). Cailler became the pioneer in mechanizing the steps in the process.

Drinking chocolate remained popular in the 19th century and the determination to resolve some of the resulting difficulties such as bitterness led to the discovery of other chocolate by products. In the Ghirardelli Factory, they used to hang the beans held in a cloth and subjected it to heat. Allowing the butter to drip and produce low fat cocoa solids. Butter became the by-product which was used in making cosmetics as a fat. As a result of low fat cocoa powder, the Ghirardelli Company improved in its sales. The butter press procedure became a trade secret (Snyder, Olsen, & Brindle, 2009). Throughout the years the bitter flavor in chocolates became a manufacturing problem, Aztecs tried to do alkalization where they mixed wood ashes with chocolate, due to its complexity, a majority of the manufacturers declined to adopt the process. Fundamentally, it was important to develop better systems and equipment for the roasting, grinding and mixing chocolates so as to meet the ever growing demand in the market.

In conclusion, the demand for chocolate grew over the years. The ancient and primitive methods of production would then get outdated. The need for better quality and efficiency kicked in and innovation for better machines in the roasting, grinding, milling and mixing became important and the involved companies across huge tried find ways to improve production. The evolution from stones metates to automated steel became a reality.

References

Brenner, J. G. (1999). From Bean to Bar. In J. G. Brenner, The Emperors of Chocolate Press (pp. 91-146).

Lawrence, S. (2002). The Ghirardelli Story . JSTOR, 90-115.

Snyder, R., Olsen, B. F., & Brindle, &. L. (2009). Chocolate, History, Culture and Heritage . In R. Snyder, B. F. Olsen, & &. L. Brindle, From Stone Metates to Steel Mills .

0 notes

Photo

Chocolate in Colonial Times: Cocoa Production in the Americas

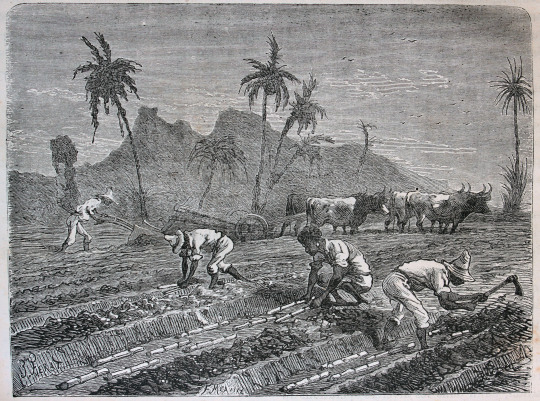

Ferry (1981) discloses that in the 15th century, the Caracas did not have enough human resources or mineral sources that would sustain its economy. According to a report released by the royal treasurer to the kin, it indicates that the Caracas started to engage in economic activities, selling agricultural products such as tobacco and wheat. Tobacco became a principal export which was then followed by wheat flour and small amounts of sugar. Cotton cloth from animal hides was also an export product which was obtained from privately owned cattle. Tobacco and hides were exported to Spain and the other items to Cartagena. On the other hand, Caracas’s imports consisted of dry goods, wine and African slaves who would then work in fields. They often paid these items with their hides, tobacco, cotton and some “cacao.” Cacao was used in the batter trade, a plant which would later revolutionize the Caracas economy.

Ferry (1981) notes that little information was available about the existence of the cacao. In the 17th century, cacao does not appear in the Caracas’ history. It was then assumed that the first plants or trees were planted by the Natives and African laborers who were under the command of Europeans. According to Ferry, in 1607 the cacao became an essential tool of trade in Caracas. In essence, it therefore seems that the boom created by the plant would not have been a result of newly planted trees, considering the difficult labor, implying that the cacao would have been native to the region. Therefore, this paper examines cacao and its impact in the Caracas economy.

Ferry (1981) asserts that it is not clear whether the first cacao to be exported from Caracas was from the indigenous lands or from the groves which were planted by the African slaves. It is important to note that during their importing activities, they received African laborers who would then be used in the agricultural fields as forced labor under the command of Europeans. Cacao then became an important plant in the Mexican economy since its growers in the encomienda system would sell their beans at reasonable prices and then later purchase slaves. According to (Walker, 2009) the proceeds obtained from cacao sales would then be used to fund the purchase of African slaves, who then would offer cheap labor to the farmers. Although, the arrival of the slaves enhanced the Caracas economy because of cheap labor, it destroyed innocent lives of the families of the slaves which further destroyed their society at large. It is also evident that during the early years, a small number of the encomenderos with grants benefited.

In the late, 16th century, the Caracas economy became vigorous and cacao became one of the most used tools of trade. According to (Pinero, 1988), the vibrant economic activities in the Caracas led to the establishment of the Caracas Company in the 1728 making cacao as the main economic activity in the region. With the advent of the Caracas Company and given monopoly powers to export cacao to Spanish markets and ensure that there were no contrabands. Pinero (1988) notes that due to the influence of the cacao, all other factors of production were now shifted from other staples such as tobacco to the production of the cacao. With all energy shifted to cacao production, several domestic and foreign linkages developed; fiscal and forward demand linkages.

Pinero (1988) in his examination realized that the forward linkages proved to be weak where 1% of the total cacao exports were sent to Spain markets in processed form, implying that there were private shipments that benefited from the company, against its establishment ideals. In principle, the production of chocolate in the Caracas was of no value to the economy since only a few people benefited. The fiscal linkage was also weak since it contributed little to the Caracas economy. Though it collected substantial amount of revenues through duties, the government did not receive higher revenues.

In conclusion, though the economy of the Caracas lacked necessary human and agricultural resources in the 16th century, Caracas was able to identify the cacao plant as a form of payment for imports. The plant later was commercialized through creating Caracas Company which would have the monopoly to process and produce cacao for export purposes. The company reaped high profits in the trade but this did not translate to high government revenues. This happened because the company would then avoid or pay lower duties on the cacao shipments to Spain and involve in the contraband business.

References

Ferry, R. J. (1981). Encomienda, African Slavery, and Agriculture in Seventeenth-Century Caracas. JSTOR, 609-635.

Pinero, E. (1988). The Cacao Economy of the Eighteenth-Century Provience of Caracas and the Spanish Caracao Market. JSTOR, 75-100.

Walker, T. (2009). Establishing Cacao Plantantion Culture in the Atlantic World. In T. Walker, Chocolate: History, culture and Heritage (pp. 543-557).

0 notes

Photo

Chocolate in Colonial Times: Consumption Patterns in Europe and America

The history of chocolate dates back to 1777 when Captain Moses Greenleaf introduced chocolate to his army. Later, English colonies in North America were introduced to chocolate leading to the broad penetration and consumer revolution in the 18th century. Although chocolate was prevalent among indigenous people in South and Central America, Spanish explorers led to the migration of chocolate to Europe and other British colonies. In the 18th century, there was a widespread use of chocolate in America and Europe for either personal consumption or other diplomacy matters (Walker, 2008). Chocolate was widely used and an essential part of the military diet during the colonial period. Chocolate drinks gave soldiers the energy required to fight and carry out their responsibilities.

The preparation of chocolate was done in specifically designed pots. The preparation often began with the grating of chocolate into the pots whereby other flavors were added to adjust tastes. Some common sweeteners included vanilla, cinnamon and rose water. Other variations of chocolate for the army included wine chocolate. Additionally, Mayan experts in cacao beverages later introduced the flavoring of chocolate with vanilla and achiote (Walker, 2008). The different recipes and preparations of chocolate were based on the tastes of different groups of people such as, Indigenous American communities and Europeans.

American colonies were introduced to chocolate by the Spanish when it arrived in Florida in 1641. Cocoa became a major American colonial import as it was appreciated by all individuals from varying social classes. The wide spread use of chocolate led to the provision of the drink as rations during the American revolutionary war and even as payment to some of the soldiers (Loveman, 2013). Among the factors that led to the growth in popularity of chocolate was a letter by Thomas Jefferson to John Adams claiming that chocolate was superior for nourishment and health when compared to coffee and tea. In around 1670, chocolate made landfall in Boston leading to a rise in demand and fast spread of chocolate use. Colonial chocolate was characterized by large bricks based on the technique and technology that was available at the time. Mills were used to grind the bricks into smaller particles. The chocolate was then sold in boxes.

The introduction and widespread use of chocolate in Europe was preceded by the stumbling of the Europeans in Mesoamerica. Cocoa beans were common currency among the indigenous groups in America. The introduction of chocolate in Europe led to widespread popularity and increased the demand. Rise in demand saw Europe looking into its colonies to increase their supply of cocoa (Margarita & Quentin et al, 2019). Europeans spread cocoa plantations into the Philippines among other colonies leading to the establishment and growth of the cacao industry.

Cocoa consumption patterns in Spain are associated with the Spanish hot chocolate. The flavor was developed after the introduction of cocoa in Europe where European palates were discontented with the traditional chocolate recipes. Their variety of hot chlorate was prepared using sweeteners such as cane sugar and cinnamon. The development of varying recipes led to the development of fashionable chocolate cafes in cities across Europe. The consumption patterns of cocoa in the colonial times was influenced by different cultural factors. However, the prevalent use of cocoa in contemporary society was fuelled by consumption patterns in the colonial times.

References

Loveman, K. (2013). The Introduction of Chocolate into England: Retailers, Researchers, and Consumers, 1640-1730. Journal of Social History, 47(1), 27-46. Retrieved October 4, 2020, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/43306044

Margarita de O. & Quentin P., et al. (2012). CHOCOLATE II: Mysticism and Cultural Blends. Margarita de Orellana.

Walker, T. (2008). Cure or Confection? Chocolate in the Portuguese Royal Court and Colonial Hospitals, 1580-1830. Chocolate: History, Culture, and Heritage. 561-568. 10.1002/9780470411315.ch41.

0 notes

Photo

Chocolate Encounters: Mexicas and Spaniards

Norton (2006) reveals that despite its incredible prevalence in the modern-day world, chocolate was at one time considered a delicacy in some parts of Mesoamerica about 1,000 years ago. The researcher explains that the cacao tree derivative was first used among the Mayans and the Aztecs; a fact that explains why the plant is considered one of the defining elements of their cultures. Such contextual observations present multiple questions on the manner in which chocolate became so widespread and popular. The current review undertakes an exploration of the manner in which chocolate permeated European societies and the ways in which cacao created a dynamic relationship between Old World and New World cultures.

To appreciate the manner in which the Old World fostered chocolate interactions with the New World, Earle (2012) explains that one must undertake a deeper review of the historical contexts that led to the ‘internationalization’ of the cacao product. In the text The Columbian Exchange, Rebeca Earle considers the voyages of Christopher Columbus to the New world as a significant event that led to the delivery of the first cacao beans to Europe. The scholar explains that even though the coffee beans suffered neglection, Columbus insisted that the resulting drink was divine and had the ability to minimize fatigue and enhance body resistance against diseases.

The history of chocolate can be classified into three distinct phases as revealed by Nikita Harwich in her book Histoire du chocolat. In Nikita’s perspective, the first phase of the history of chocolate encompasses the beverage of the deities by reviewing the particular value of chocolate and its commercialization from Soconusco to Izalcos and finally, Venezuela. On the other hand, Nikita considers the “The Industrial Horizon” as the second evolutionary phase of chocolate which increased the availability of the product both in geographical horizons and presentations.

The assimilation of chocolate from the Mesoamerican region to European societies such as Spain was initially met with a lot of resistance. As revealed by Norton (2006), the Spaniards hated the taste of chocolate the first time they met it in areas such as Mexico. The scholar explains that such reasons greatly reveal why the visitors from Europe adopted innovative ways of enhancing the taste of chocolate by adding sugar.

Chocolate gained its popularity in the European region after the cultures of the Old World and those of the New World had started to mingle and clash. As revealed by Nikita (2013), the intense commercialization of chocolate presented an avenue for effective diffusion of this product from the New World to the Old World. Norton (2006) explains that while Spain started gaining its position as the world’s major consumer of cacao products, the production centers in Latin American areas begun to lose their ground in a steady manner. Earle (2012) explains that instead, the major areas of demand shifted to the north of the Pyrenees then crossed the Atlantic.

In conclusion, the exchange of chocolate from the Old World to the New World resulted from the historical interactions established among the populaces of these two regions. In particular, the classical voyages made by Christopher Columbus had a strong effect in the internationalization of chocolate. However, people in the Old World were faced with the obligation of incorporating a few innovative mechanisms to ensure that the products suited their tastes.

References

Earle, R. (2012). The Columbian Exchange. In The oxford handbook of food history (pp. 341-357). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Harwich, N. (2013). Histoire du chocolat. Desjonquères Editions.

Norton, M. (2006). Tasting empire: chocolate and the European internalization of Mesoamerican aesthetics. The American Historical Review, 111(3), 660-691.

0 notes

Photo

Chocolate Origins: The Cacao Tree and Mesoamerican Ancestors

Chocolate finds a household name as one of the most intriguing delicacies in global history. Prufer and Hurst (2007) explain that even though chocolate originated from the Amazon forest, its acceptance in other cultures has made it a staple of civilization all over the globe. Reents-Budet (2006) demystify that the Mesoamerican ancestors enjoyed cocoa nearly 4,000 years ago. Effective scholarly works such as Edgar’s The Power of Chocolate has presented convincing evidence that Ancient Mesoamericans could have domesticated the cocoa tree from as early as the fourth and the fifth centuries AD.

Reents-Budet (2006) considers the Olmec village of El Manati as the earliest source of evidence on the patterns of cocoa consumption all over the globe. In the source The Power of Chocolate, Edgar reveals that archaeological materials such as broken pieces of ceramic pots collected in the El Manati village tested positive for the presence of theobromine; a chemical marker used to identify the presence of past cacao. Scientifically, the cacao tree is a member of the genus Theobroma which in Edgar’s translation represents the phrase “food of the gods”. Such a premise reveals why Prufer and Hurst (2007) explain that the cacao plant is strongly associated with a range of prestigious and ceremonial initiatives throughout the Mesoamerican region. The researcher demystifies that in historical literatures such as Vuh; one of the most adored Maya books of creation, cacao is considered as one of the food materials that God adopted when creating the first human. Such a premise explains why cacao is adopted as an element of identity and rites of passage in these communities (Prufer and Hurst 2007).

To date, archeological evidences has shown remarkable findings on the history of chocolate usage over the years. As revealed by Edgar (2010), the discovery of traces of cacao in the Pueblo Bonito ceramic remains along the Chaco Canyon was an important discovery in understanding the prevalence of cacao in the Mesoamerica context. The scholar explains that the identification of cacao in the Pueblo Bonito flower vases gives a clear indication of the intensive trade relations that transpired between the Mesoamerican region and the southwest of the United States about 4000 to 5000 years ago. In The Power of Chocolate, Edgar demystifies that the vases containing theobromine depicted some levels of similarities in their geometric motif to the Mayan items adopted in the practices of holding cacao. Such a premise greatly reveals that there are tendencies that the cacao used in these days was in liquid form as it showed the ability to soak in the ceramic vessels put to use.

Most research works heavily derive the history of cacao usage among human societies from diverse pieces of archaeological evidences. Prufer and Hurst’s Chocolate in the Underworld reveals that a small bowl holding cacao seeds was discovered from a southwestern Belize remote case in 1995. The scholar demystifies that the seeds formed an essential part of the sophisticated funerary sacrifices that were buried with the decapacitated human remain. In their view, Prufer and Hurst (2011) believed that the burial contexts must have dated back to the 5th and 4th centuries AD; an element that depicted the seeds as the oldest intact archaeological extractions in the Mesoamerican region.

In conclusion, chocolate occupies an essential part in the human society. Historical pieces of evidence have revealed that the ceremonious cacao beans have formed part of the human race for over 4000 years. In particular, scholarly evidence considers the Mesoamerican region as one of the most significant points of origin of the cacao tree. However, cultural diffusion contributed to the distribution of the cacao seeds and products across the globe, mystifying their origins until historians and researchers began studying the origins. As we have seen, cacao has been around far longer than the modern forms we see today. The cacao bean played a pivotal role in Mesoamerican societies and serves to establish a more comprehensive context of the culture within those societies.

References

Edgar, B. (2010). The Power of Chocolate. Archaeology, 63(6), 20-25.

Prufer, K. M., & Hurst, W. J. (2007). Chocolate in the underworld space of death: Cacao seeds from an early classic mortuary cave. Ethnohistory, 54(2), 273-301.

Reents-Budet, D. (2006). The social context of Kakaw drinking among the ancient Maya. Chocolate in Mesoamerica: A cultural history of cacao, 202-223.

5 notes

·

View notes