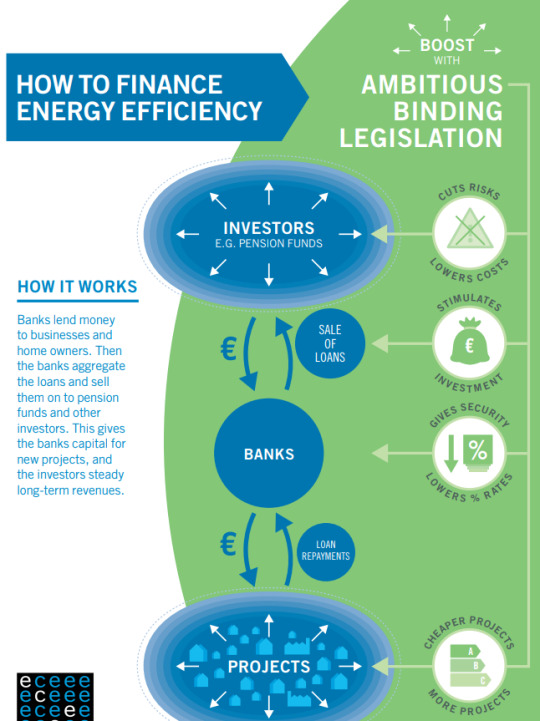

Text

1 note

·

View note

Text

Les Bases [Saint-Denis-sur-Richelieu] par Écorce architecture écologique

- -

« La conception architecturale des volumes s’inspire des anciennes maisons environnantes, en privilégiant la sobriété par la symétrie et la séparation fonctionnelle. Un volume bas et délicat accueille les espaces de nuit, tandis qu’un volume plus haut et prédominant démarque les espaces de vie.

Nous avons également incorporé et réinterprété des éléments singuliers et représentatifs de ce contexte, tels que les cheminées au toit et les jeux de volumes.

Le projet a été conceptualisé selon les principes de passivhaus, atteignant un taux de changement d’air à l’heure de 0.27 CAH@50Pa et en tirant parti des avantages bioclimatiques tels que l’orientation solaire et la ventilation naturelle. Les ouvertures ont été soigneusement conçues pour optimiser la luminosité naturelle sans provoquer de surchauffe.

L’aspect écologique a été mis de l’avant par la construction d’une enveloppe hautement performante, avec une isolation supérieure de 30 % par rapport au code de construction, ce qui permet d’atteindre un score de 47 sur l’échelle du Home Energy Rating System. Cela signifie que Les Bases est 53 % plus efficace sur le plan énergétique qu’une habitation standard neuve. De plus, des principes tels que la charpente avancée, qui réduit la quantité de structure nécessaire à la construction tout en maximisant l’isolation, et l’utilisation d’une dalle monolithique sur le sol, permettent de réduire l’empreinte carbone du projet, son impact environnemental et de garantir sa durabilité et sa résilience pour les années à venir. La résidence est en voie de certification LEED de niveau platine. »

- -

Architecte : Emerick Duquette

Photographe : Maxime Brouillet

Constructeur : Noveco Entrepreneur Général

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Last year, troubled by the seeming intractability of these problems, I began looking for solutions outside the United States. Could the answer be rent control, as in Berlin? It might have seemed that way a decade or so ago, before investors and new residents began pouring into the city, causing land values to quintuple; now, despite rent-stabilization laws, even the apartments that no one else wanted to buy 15 years ago are huge moneymakers. Many residents with affordable rental contracts are locked into them because it would be too expensive or competitive to move. Frustrated by the housing squeeze, tenant organizers recently put forth an “expropriation” measure, which called for landlords with more than 3,000 units to sell their holdings back to the government at below-market prices. In a 2021 referendum, 59 percent of Berliners voted in favor of it, but it’s not clear whether it will ever be implemented.

Could the answer be loosening zoning restrictions, as Tokyo did in 2002? That has certainly helped. In 2014, there was more home construction in the city than in all of England. Since then, home prices have stabilized. Tokyo is largely celebrated as a model by YIMBYs (members of the “yes, in my backyard” movement) because they like its market-driven approach to housing abundance. They often point out that the city builds five times as much housing per capita as California. But Japan is a very different market because of its earthquake risk: Because regulatory codes and mitigation technologies are ever improving, structures often fully depreciate within 35 years. Older homes are often undermaintained because there’s little expectation that any investment might be recaptured upon resale; they’re thought of like used clothing or cars — you resell at a loss.

Auckland, New Zealand, might seem like a more applicable example. In 2016, the city, which has one of the most expensive housing markets in the world, “upzoned” 75 percent of its residential land, increasing its legal capacity for housing by about 300 percent in an effort to encourage multifamily-housing construction and tamp down prices. In areas that were upzoned, the total number of building permits granted (a way of estimating new construction) more than quadrupled from 2016 to 2021. As intended, the relative value of underdeveloped land increased, because it could suddenly host more housing, and the relative value of units in densely developed areas decreased, tempering sky-high prices. But there are limits to what upzoning can do. Often the benefits of allowing greater density are captured by developers, who price the new units far above cost. It doesn’t offer renters security or directly create the type of housing most needed: affordable housing.

That’s what differentiates Vienna. Perhaps no other developed city has done more to protect residents from the commodification of housing. In Vienna, 43 percent of all housing is insulated from the market, meaning the rental prices reflect costs or rates set by law — not “what the market will bear” or what a person with no other options will pay. The government subsidizes affordable units for a wide range of incomes. The mean gross household income in Vienna is 57,700 euros a year, but any person who makes under 70,000 euros qualifies for a Gemeindebau unit. Once in, you never have to leave. It doesn’t matter if you start earning more. The government never checks your salary again. Two-thirds of the city’s rental housing is covered by rent control, and all tenants have just-cause eviction protections. Such regulations, when coupled with adequate supply, give renters a level of stability comparable to American owners with fixed mortgages. As a result, 80 percent of all households in Vienna choose to rent.

The key difference is that Vienna prioritizes subsidizing construction, while the United States prioritizes subsidizing people, with things like housing vouchers. One model focuses on supply, the other on demand. Vienna’s choice illustrates a fundamental economic reality, which is that a large-enough supply of social housing offers a market alternative that improves housing for all.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

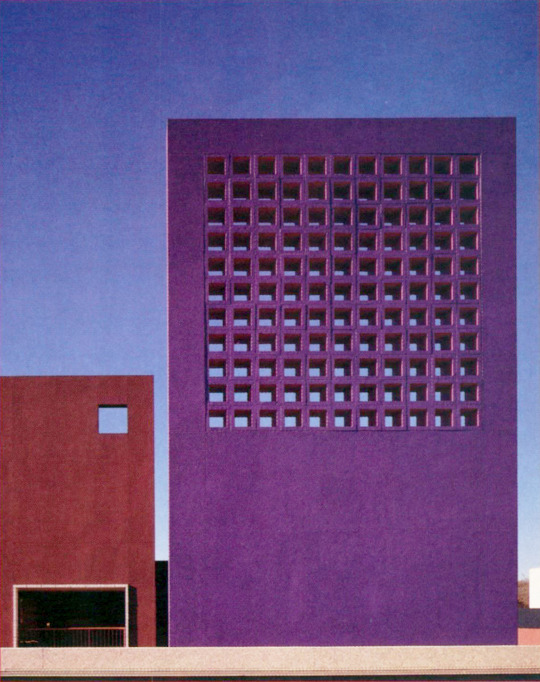

Legoretta Arquitectos, Solana Complex, Westlake, Texas, 1985

507 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Josef Albers, City,

Musée d'Art Moderne de Paris, 2021

61 notes

·

View notes

Photo

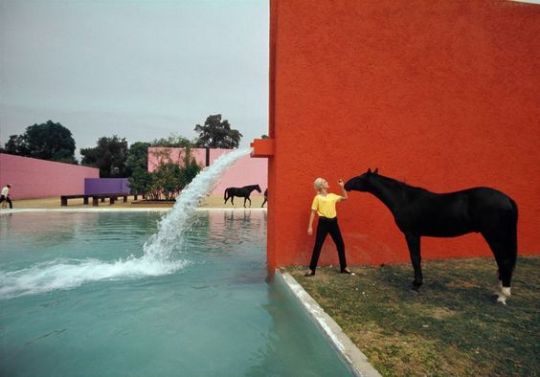

Rene Burri

Mexico City. Cuadra San Cristóbal. 1969. Los Clubes (1966-68) by Mexican architect Luis Barragan.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Situé au cœur de Baie St-Paul, l’Hôtel La Ferme se veut un vaste complexe hôtelier composé de cinq pavillons inspirés des bâtiments de ferme d’autrefois. Chaque pavillon offre une architecture, un décor ainsi qu’une ambiance particulière rendant hommage au patrimoine culturel et historique du lieu.Un des grands défis de ce projet était de créer un lieu mémorable et dynamique, à l’image même du client, ancien dirigeant du Cirque du Soleil. Lieu de diffusion de la culture Québécoise, de l’art et artisanat local, lieu de séjour et de passage, lieu d’échange et de partage, l’hôtel se devait aussi d’être bien reçu dans sa communauté d’accueil constituée entre autres des Petites Franciscaines de Marie et de la population de Baie-Saint-Paul. L’image projetée ainsi que l’échelle du projet dans le paysage étaient donc critiques pour l’acceptation du projet et son appropriation par la communauté.

Parti architectural

Le plan directeur repose essentiellement sur le morcellement, en plusieurs pavillons, des différents éléments programmatiques afin de permettre une meilleure expérience du lieu, tant sur le plan du paysage que des espaces intérieurs. Cet éclatement volontaire du programme a aussi permis de réduire considérablement l’échelle du projet, favorisant une meilleure intégration dans le contexte historique et naturel la ville de Baie-Saint-Paul. Le concept « d'espace entre », c'est-à-dire tout ce qui se passe, se vit et se voit entre le bâti, est ici exploité de manière allégorique. Ainsi, chaque pavillon, par sa localisation sur le site, son orientation et sa forme offre une expérience unique au visiteur, stimulant ainsi sa curiosité et son intérêt à revenir au pôle de la ferme afin d'expérimenter une autre chambre, une manière différente d'habiter le site.

Outre leur caractère pavillonnaire, les bâtiments implantés sur le site se veulent de facture contemporaine. Leurs volumes, simples et épurés, rappellent certains traits de l’architecture vernaculaire. À titre d'exemple, soulignons les grandes portes de granges rouges en acier qui coulissent le long de la façade principale du pavillon d’entrée et qui animent le projet. Les principaux matériaux utilisés sont naturels, soient le bois et l’ardoise du Québec. Posée sur des murs verticaux, ils donnent une texture et une couleur au projet qui contribuent à son intégration au paysage.

Pavillons

Le pavillon principal, baptisé la Ferme en mémoire de la ferme Ambroise-Fafard qui occupait le site avant d'être incendiée en 2007, se retrouve en avant-plan du complexe hôtelier. Sa façade dynamique et translucide devient, en quelque sorte, la vitrine du projet sur la communauté, permettant aux passants et visiteurs de deviner les activités qui se déroulent à l'intérieur. S'élevant sur trois étages et composé de trois corps de bâti disposés de manière à délimiter une cour intérieure, ce pavillon rappelle l'échelle et la configuration de l'ancienne ferme, élément majeur de la mémoire collective locale. Exposée à la lumière du soleil et orientée face au fleuve, la cour intérieure se veut le coeur du projet, un noyau autour duquel s'organisent plusieurs espaces publics tels que le foyer, la salle multifonctionnelle, le restaurant, la gare et le marché public.

En plus des principaux espaces publics, le pavillon la Ferme comprend deux blocs de chambres. Plus traditionnel, le premier secteur est niché au niveau supérieur du pavillon, profitant d'une proximité avec les différents services de l'hôtel. Abondamment fenêtrées, les chambres de ce secteur permettent à l'usager de vivre pleinement et simultanément l'architecture et le paysage. Le deuxième secteur de chambres se situe pour sa part au-dessus de la gare desservant le site et propose une toute autre expérience aux usagers. Ceux-ci peuvent louer une place dans l'une de ces chambres pouvant être partagées par quatre usagers. Le caractère collectif de ces chambres se veut donc à l'image d'une clientèle de voyageurs actifs, à la recherche d'une ambiance particulière, définie par les occupants eux-mêmes.

Les autres chambres de l’hôtel sont réparties dans quatre pavillons différents sur le site du pôle de la ferme. Dans cet esprit, l’usager est amené à bien vivre le site dans son cheminement aux chambres. Pour aller à sa chambre, le visiteur déambule à l’extérieur et expérimente le terrain, ses vues extraordinaires sur les montagnes et le fleuve, sa végétation, ses grands trottoirs de bois. Cette expérience de dépaysement, à l’image du lieu, permet au visiteur d’utiliser ses sens et de vivre en osmose avec le paysage. Les quatre bâtiments, soit le Clos, le Moulin, la Bergerie et la Basse-Cour, offrent des expériences diversifiées et propres à chacun d’eux. Le Clos propose une ambiance monastique, le Moulin par sa configuration en hauteur, s’ouvre davantage vers le paysage et offre des suites plus luxueuses. Quant à la Bergerie et la Basse-Cour, l’ambiance y est plus familiale par la proximité du SPA, des aires de jeu et de repos de l’hôtel situées en dessous. C’est donc dans la diversité des ambiances que les chambres de l’hôtel du Pôle de la ferme se définissent. La matérialité de celles-ci est également une référence pour les usagers au concept du projet par l’utilisation de matériaux naturels et bruts. Les planchers sont en bois et en céramique et les éléments de mobilier intégré et d’architecture d’intérieur sont en bois brut afin que le design global de la chambre soit en relation avec l’architecture des bâtiments du projet.

0 notes

Text

https://thewalrus.ca/why-is-canadian-architecture-so-bad/?fbclid=IwAR1UeEc02olvoME6FxiXXhVh5euEPW2w9FUx6g1u9K3yR1NkkVr1vpS3bHY

Even the United States has more compelling architecture than Canada, particularly in its big cities. Chicago’s gorgeous Millennium Park, for instance, was the result of a public-private partnership that relied heavily on the philanthropic sector. Wealthy individuals, as well as foundations and other organizations, pitched in $220 million (US) for the park and an adjoining arts theatre—almost half of the total cost of the project. Its most recognizable feature, a $23 million bean-shaped mirrored sculpture, was privately funded through donations. In Canada, philanthropy is most generous toward hospitals, schools, and the arts.

He disagrees that Canadian architecture is uniformly ugly, although he does call a lot of it “mediocre.” Still, he points out that there are pockets of excellent design that partly redeem us. And some cities do a good job of highlighting the natural landscapes abutting the built environment. Some even take design risks. “You have tiny little rinky-dink towns in Quebec that are building beautiful libraries, performing-arts centres, and often with relatively young firms,” he tells me.

“But,” he continues, “I think Canadians—and this is something that sort of drives me nuts, and I think it’s not just particular to [architecture]—we’re just a bit passive, right? I mean, you could say the same when it comes to the environment. We’re really not doing that much for the most part, and Canadians aren’t really demanding that their politicians do very much either.”

There’s a lot of truth in Livesey’s estimation, but I suspect our commitment to accepting “good enough” isn’t merely about a lack of empowerment or abundance of ignorance. It’s also about our Kafkaesque procurement processes and how our local governments often hand cities over to private developers. Fundamentally, though, it represents our aversion to risk. Why rock the boat when something “safe,” functional, and cheap will suffice?

We can’t even blame the weather for our approach to design. Norway has cold winters too, but it has somehow managed to create an innovative movement where structures are built or renovated to produce more energy than they consume (called “energy-positive building”). And the buildings are beautiful too.

Not here, though. “The predominant approach to the design and construction of buildings across Canada has been ‘build cheap, maintain expensive,’” write Ted Kesik, Liam O’Brien, and Terri Peters in a 2019 design guide for multi-unit residential housing.

In many instances, “build cheap” also means “build ugly”—not because good design necessarily costs more but because we have conned ourselves into believing that it does. In reality, good design simply means making more creative choices with the money you have—something that is simply beyond the capacities and capabilities of the people with the rubber stamps. In many ways, our devotion to fiscal conservatism has caused us to settle for buildings that don’t meet even the most basic standards of environmental responsibility. Kesik et al., in their guide, lambasted building designers for allowing a generation of drafty, poorly insulated public housing to be built.

While Livesey isn’t so cynical to think that Canadian architecture as a whole is a chore to look at, he sees many newer private-sector buildings suffering from similar ailments: too much glass, cheap building envelopes, subpar insulation, uninspired design. Canada’s downtowns are still stuffed with cranes piecing together gleaming towers with floor-to-ceiling glass—a design choice that sucks up excessive amounts of electricity in both the summer and winter months. Private developers push for this kind of design because it is relatively easy and inexpensive to construct; it almost always get approved by cities; and when combined with cheap materials, it is the quickest way to get returns into the pockets of promoters and investors.

These motivations come at a cost. In 2014, the CBC reported glass panels falling off the facades of newly built condo and hotel towers in downtown Toronto, including the Shangri-La luxury hotel, where the most basic room goes for a minimum of $575 a night. In another Toronto high-rise, tenants contend with wildly fluctuating water temperatures seemingly due to improperly installed valves. Then there’s Vancouver’s enduring leaky condo crisis, in which tens of thousands of homes built in the 1980s and 1990s have been flagged for water leaks.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Landscape with a Sunlit Streamca, 1877

Charles-François Daubigny

433 notes

·

View notes

Text

https://www.facebook.com/9539797771/posts/10159152497992772/?d=n

Projet BERRI [Montréal] par La Firme

- -

« Les traditionnels triplex de Montréal sont rarement arrimés aux réalités contemporaines, notamment en matière de division des pièces, de luminosité et de fluidité de l’expérience quotidienne. Leur transformation exige donc un travail particulièrement complexe et minutieux au moment de dessiner les plans.

Cet espace de 1000 pieds carrés est dorénavant à l’image de ses propriétaires : un lieu moderne et épuré, où les enfants, les livres et une passion pour la cuisine sont à l’honneur.

La transformation d’une grande pièce en deux chambres pour enfants, l’aménagement d’un vestibule japonais (genkan), l’addition d’une fenêtre jumelle dans une cuisine métamorphosée et le grand geste d’ébénisterie modelant les armoires et les étagères en merisier parcourant salon, salle à manger et cuisine, ajoutent élan et rangement à cet environnement plutôt étroit.

Dans la cuisine, on note l’îlot en granit servant de comptoir et de coin-repas ainsi que le bloc sur mesure tout en inox brossé constituant à la fois l’impressionnant comptoir, l’évier et le dosseret.

Pour la salle de bain, la céramique de la douche à l’italienne propose un motif personnalisé inventif. Clin d’œil rétrofuturiste, la pharmacie manifeste son éclat avec un élégant halo orange cadrant le meuble dont l’intérieur, tout aussi orange, tranche avec le vert enveloppant de la pièce.

Dans ce rez-de-chaussée profitant de nouvelles divisions, les contrastes s’expriment entre choix de teintes et de matériaux, créant des agencements et des rappels participant à l’harmonisation de l’ensemble. On note que la Firme signe entre autres le banc et le porte-manteau du vestibule ainsi que les lampes de chevet de la chambre principale. »

- -

Photos : Ulysse Lemerise Bouchard

0 notes

Text

Cultural supports make B.C. Indigenous housing project a real home

For a few nights after she moved into a Victoria housing complex this past August, Theresa Gibbons slept with her door open, unaccustomed to having space to herself.

Ms. Gibbons, 53, has been homeless for much of the past decade, during which she stayed in “pretty much every shelter in Victoria.”

“When you get into shelter mode, it’s really hard to get out of that mindset,” Ms. Gibbons said in a recent telephone interview from Spa’qun House, a modular housing project for Indigenous women who are experiencing or at risk of homelessness.

“So the door was a big deal – some of the people who moved in were like, ‘Oh yeah, I’ve got my own bathroom, I’ve got a door I can close.’

“But living with 60 to 70 people for six or seven years, it can be a little unnerving with it being quiet.”

Adjusting to the quiet, and a door she can close, is part of a bigger journey for Ms. Gibbons – and part of an overall approach to health and housing at Spa’qun House.

Billed as the first of its kind in B.C., the project provides culturally supportive housing. The model includes elements typical of B.C.s existing supportive housing projects – meals, counselling and round-the-clock staffing. But it also features cultural elements such as access to traditional foods, land-based healing programs and regular visits from elders.

The province put up $3.8-million to build and launch the project, which opened in August and is run by the Aboriginal Coalition to End Homelessness Society (ACEH), with support from Vancouver-based Atira Women’s Resource Society.

Although relatively small, with 21 units, it has a big ambition: to showcase a housing model that gets people off the street but also provides a sense of identity and, through that, a route to healthier lives.

Spa’qun House grew out of an earlier, three-year project involving ACEH and several agencies that focused on a “priority one” group. These were people with high needs, including mental-health and addiction issues, who had been banned from Victoria housing or shelter services for disruptive behaviour, including violence. There were 74 people in the pilot project, 20 of whom were Indigenous.

The project highlighted gaps when it came to Indigenous housing needs, particularly those of women fleeing violence, ACEH director Fran Hunt-Jinnouchi said.

“I, like many people, probably drove through our city and assumed that our Indigenous people are being taken care of,” Ms. Hunt-Jinnouchi said. “I have since come to learn that the specific group or target population that we are now focused on is almost doubly marginalized, because Indigenous housing has very much focused on affordable or family and low-income housing.

“That does not open the doors up to any of the people we are working with.”

That group includes people who live with chronic medical issues, have a history in the criminal-justice system and may have been dependent on the shelter system for years, even decades. A referral process involving provincial housing agency B.C. Housing and various housing providers came up with 95 candidates for spots at Spa’qun House. Twenty-one were selected.

Ms. Gibbons said she became homeless after she couldn’t afford to pay her rent and was evicted. Health problems and the deaths of several close relatives over a short period compounded her problems. She had back surgery for spinal stenosis in February.

Of Cree descent, she said she was not raised with strong cultural ties and is currently trying to learn more about her heritage.

“They [Spa’qun House] are bringing in traditional things and I’m grateful for that. Because it’s the start of a learning point for me, for possibly [learning about] my background.”

Ms. Gibbons said she is focusing on regaining her mobility and hopes to return to work with SOLID, a Victoria drug users’ group with whom she was a peer counsellor before her operation.

ACEH designed Spa’qun House with an eye to developing a “decolonized harm-reduction framework.”

As Ms. Hunt-Jinnouchi describes it, that framework – still evolving – would incorporate culture, language and healing and, ideally, a path toward recovery.

“The housing is just the first step … their Indigenous self, their cultural self, needs to be ignited and nurtured and supported,” she said, adding that culturally supportive housing, in and of itself, is not enough.“

If we do not provide pathways to healing and recovery … we are just kind of prolonging the inevitable in a warm setting. And that is not enough. It should not be enough in society, whether you’re Indigenous or non-Indigenous.”

Still in its infancy, Spa’qun House has had to pull back on programming and visitors because of COVID-19. But the residents – referred to as family members – are adjusting, getting used to doors that close and beds they can return to each night.

Juanita Valdez, who grew up in Victoria and said she has lived outside and in shelters for the past few years, said she appreciates being able to keep pets – she has two birds – and is becoming accustomed to living inside and having a regular routine. Ms. Valdez, 34, describes herself as Coast Salish.

Asked what she hopes for a year from now, she pauses for a long moment and then says she is taking things day by day.

“It’s been pretty successful, coming back to life,” said Ms. Valdez, who likened years of homelessness and heavy drug use to sleepwalking or waking nightmares because sometimes she would be awake for days at a time.

“It’s that kick I was looking for – so I am glad I was awakened, and now I am living my days from morning to night.”

1 note

·

View note

Text

0 notes