Photo

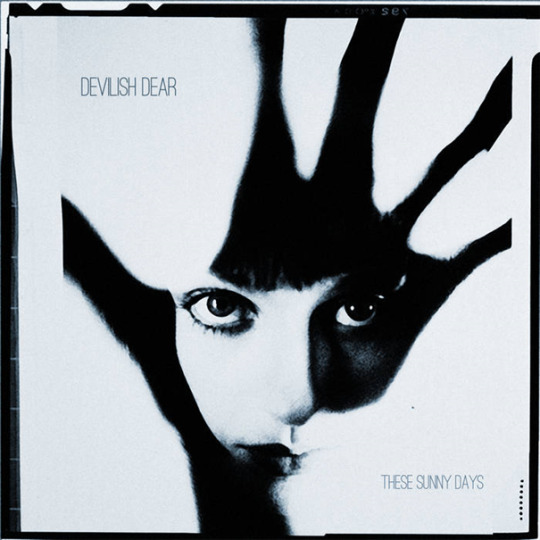

DEVILISH DEAR - THESE SUNNY DAYS (2017): 9/10

Okay, so this album really has fuck all to do with progressive rock but I don’t give a shit cause this may be the best album I’ve heard this year and seeing as how it's still 2017, I want to talk about this Brazilian shoegaze band that released its debut album this year. Actually, while there isn’t much stylistic overlap between shoegaze and prog rock, their historical developments are somewhat similar when you think about it. Both were treated with disdain by most music press outlets for their perceived elitism, and both faded away during the rise of more hard-rocking and accessible genres (punk rock in the case of prog, and grunge in the case of shoegaze). And just like the old classic prog bands, shoegaze artists are now making a comeback twenty years after the genre’s original decline, with bands such as My Bloody Valentine, Slowdive, Ride and Lush all having reunited (at least temporarily) and releasing new original material at some point in the past five years. Devilish Dear, led by guitarist, drummer, keyboard player and composer Braulio Jorge, may at first seem like a typical exponent of this shoegaze revival, but this appearance is deceptive, as this group definitely makes an effort to stand out among its peers.

The opening track, the brief “Face Without Eyes”, illustrates what style this band is going for. First of all, they’re not holding back on the shoegazing: the music on this album is drenched in countless overdubs and reverb effects in addition to ambient sound effects on a few tracks, to give a true wall-of-sound experience. Second, the vocals, provided by Michelle Modesto, manage to perfectly walk a tightrope between dream-like and imposing; to get an impression of what Modesto sounds like, imagine a slightly more assertive Elizabeth Fraser with a lower voice and a cute Latin American accent. But the most important thing that sets Devilish Dear apart from its competitors is their harmonic language, with major seventh chords and strange progressions all over the place to add an element of unpredictability. This is used to greater effect in "Time To Live A Little" which is actually a full-length song (isn't it relaxing to finally deal with a band that mostly makes songs of 2 to 3 minutes instead of 30-minute opuses?). One might even hear jazz influences emanating from these chords (in fact, I did write a jazz arrangement for this song and tried to have the band I’m in perform it, but convincing sane humans to play a jazz arrangement of a shoegaze song is sadly a more daunting task than I anticipated).

The title track, which comes in between the two aforementioned songs, is instrumental and is a more traditional riff-based shoegaze track, although it does have a 7/8 rhythm, unusual for the genre. It also has a gloomy, bittersweet feeling to it in spite of its title. “3 AM” on the other hand is a really strange track, not only in terms of its melody and chords, but also its arrangement. The lead instrument here is a synthesizer instead of a guitar, and this combined with the robotic drum pattern and the electronically altered vocals give the track an electronic feel that somehow still manages to be compatible with the shoegaze aesthetic. After two minutes it fades out into a bunch of noise before leading into “Pointless Status”, which starts off as an ominous march-like tune but then ends up as a slightly altered reprise of the theme from “3 AM”, this time with the guitar on top. This is followed by "This Isn't Happiness" another instrumental which is based on a moody synth melody, around which Jorge constructs a landscape of different melodies on his guitar and keyboards.

“Handstand” is the only track that feels unnecessary, being yet another instrumental reworking of the progression from "3 AM" and "Pointless Status" without anything particularly interesting being added. Finally, “I Wanna Do It”is the track that feels the most out-of-place, as it's essentially a techno march dominated by synthesizers and drum machines without a guitar in sight, although it still adheres to the overcrowded production and gives off the same hypnotic effect as "3 AM". At 6 minutes, it does slightly overstay its welcome, but if you sit through it you'll be rewarded with a bonus track (assuming you downloaded the album, and why wouldn't you? It's free) called "Mad Future": a brief sequence of distorted guitar chords which may be the most upbeat track on the album.

This album really hit a note with me, and I strongly encourage you to check it out if you're interested in alternative rock, electronic rock, wall-of-sound production or throwbacks to the early nineties. Listen to it here and be enlightened.

Best song: 3 AM

1 note

·

View note

Photo

REUBEN GINGRICH - BLUE ISLAND (2017): 8/10

Well, this isn’t progressive rock! Well no, it’s not, but… isn’t it close enough? I mean, progressive rock came into existence when rock musicians tried to escape the constraints of rock music by taking influence from jazz while jazz fusion came into existence when jazz musicians tried to escape the constraints of jazz music by taking influence from rock. Among other things, but you get the idea, and now that I have an excuse to review this album, let’s dive right into it. Or rather, let’s dive right into the ocean and resurface on Blue Island.

Reuben Gingrich is a drummer and drum teacher from Los Angeles who has been uploading videos to YouTube since 2006 and gradually built up a small fanbase before he embarked on a number of online collaborations and eventually released his debut solo album Blue Island earlier this year. Even though Gingrich serves as official band leader and writes most of the songs, the music on this album is not really drum-centric. Gingrich keeps down the beat with great skill, but the most prominent player on the album is keyboard player Andrew Lawrence, who plays most lead parts and solos on his square wave generator (although guitarist Samuel Mösching and saxophonist Corbin Andrick also supply a solo here and there) in addition to using his array of synths and pianos to create a ton of background layers. Also, a lot of tracks have the reverb all the way up and incorporate nature sound effects, as if to actually give off the impression of a remote blue island in the middle of the ocean.

Almost all songs on the first two thirds of the album are solid jazz fusion offerings, from funky synthy jams such as “Emerald Flames” and “Awaken” to more ethereal piano-led tunes like “Sun” and “Kokedera”. A particular standout is a cover of the song “Secret Of The Forest” from Chrono Trigger. The original already had a jazz-like cadence and chord progression, so this version sounds pretty close to the original. Lawrence and Andrick also both play shining solos on it that very well accentuate the song's mysterious and melancholic mood. Definitely check it out if you're at all interested in video game songs being recreated with live instruments.

But the real treats of the album are when Gingrich’s band is joined by other online musicians with whom he’d already collaborated in the past. The aforementioned "Emerald Flames" features YouTube-based bassist MonoNeon, a fascinating virtuoso who manages to assume lead position in certain parts of the song and even plays a shred solo on his bass guitar during the bridge. It's surpassed only by "Mystique", a funny fast-paced groove which features B.C. Manjunath on 'Konnakol' vocals, which is more or less the South-Indian equivalent of scat singing. Ever wanted to hear Scatman John take it away on a fast-paced jazz tune?... Well, I suppose you could also hear the actual Scatman John do that if you wanted to, but this is the next thing that comes close.

Sadly, the album is not entirely free of filler: the final three tracks are pretty much dispensable. "Moon Machines" and "Beyond The Future" are both rather pointless and unimpressive improvised pieces, and "Hope" is a cover of the eponymous track by the Mahavishnu Orchestra that's only two minutes long. While I normally welcome any homage to John McLaughlin, there are dozens of more interesting Mahavishnu songs that Gingrich could have picked to finish the album on a high note. So kind of a weak ending, but thankfully, the tracks on this album that leave me underwhelmed are all pretty short and innocuous, so the rest of the album more than makes up for them. Overall, Blue Island is an excellent addition to any jazz fusion collection and shows that the genre is still far from dead even this far past its heyday.

Listen to the album here and check out Reuben's YouTube channel here.

Best song: MYSTIQUE

0 notes

Photo

YOWIE - SYNCHROMYSTICISM (2017): 7/10

Man, we’ve really gone mellow, haven’t we? A review of an album full of happy love songs, following one about an album full of quiet dream and folk music? Let’s pick something harsher this time. Let’s talk about music more inaccessible than Franz Kafka’s castle and more dissonant than two bloodhounds trying to sing Bohemian Rhapsody, and made by a band whose name is a homophone of Japanese gay porn.

Man, we’ve really gone mellow, haven’t we? A review of an album full of happy love songs, following one about an album full of quiet dream and folk music? Let’s pick something harsher this time. Let’s talk about music more inaccessible than Franz Kafka’s castle and more dissonant than two bloodhounds trying to sing Bohemian Rhapsody, and made by a band whose name is a homophone of Japanese gay porn.

Math rock has always sort of struck me as a genre that came into existence through the same sentiments and mentalities that once drove progressive rock, yet doesn't want to be associated with the latter out of fear of being associated with the negative stereotypes and prejudices held towards prog rock by some people (not to say that there aren't clear stylistic differences between the two genres, of course). Bands that fall under the math rock moniker can be roughly divided into two subcategories: the more well-known of these blends indie and/or emo rock with complex rhythms and time signatures and is represented by bands such as This Town Needs Guns and American Football. The other is more influenced by noise music and seems to be mostly explored by Japanese bands. Yowie (consisting of guitarists Jeremiah Wonsewitz and Christopher Trull and drummer Shawn O’Connor), despite being from Missouri, definitely falls into the latter category, and is about where you end up if the music of Conlon Nancarrow is too commercial for you. It’s easy to mistake the band's first album, Cryptooology (from 2004), for nothing but random, freely improvised noise. However, if you listen to their second album, Damning With Faint Praise (released as late as 2012; yes, this band is notorious for prolonged bouts of inactivity in between albums), it becomes more clear what they’re actually doing. The supposed random noise of Cryptooology is actually meticulously composed and played with the utmost precision. The screaming dissonant harmonies, the nigh impossible to follow rhythms that change at lightning speed, every bit of it is carefully planned out. Damning With Faint Praise departs from the same principle but has a little more mercy on its audience: the songs are more clearly divided into identifiable sections, and, unlike the last album, one of the two guitar players is relegated mostly to the bass register so that it’s more easy to detect what each instrument is doing. The result sounded like a refinement of the old formula, and yielded an album with a notably distinct and very intriguing sound.

So how much further has Yowie evolved with Synchromysticism, released five years after the band's previous album? Well... not that much further, sadly. This music is still extremely complicated, virtuosic and atonal, but if you listen to it right after Damning With Faint Praise there's not much that will catch you off guard. Like all of Yowie's albums, Synchromysticism is short, only consisting of five tracks that together make up slightly over 30 minutes, so the band does make an effort to avoid throwing too much at its audience at once, but still even I can't deny that if you listen to the whole thing in one go, it'll eventually start to sound a tad monotonous unless you pay exceptionally close attention to everything that's going on.

There is however one truly remarkable aspect about Synchromysticism which sets it apart from its predecessors and which certainly surprised me when it finally occurred to me: some of these songs are actually... catchy. Tell me you don't want to dance to the 3/4 beat of "The Fourth Wall Will Not Protect You", and tell me the menacing 7/8 melody of "Absurdly Ineffective Barricade" isn't infectious as all hell! It takes a very specific kind of talent to make the highly intricate and experimental music that Yowie makes, but it takes a whole different kind of talent to add an element of immediate memorability and 'toe-tappability' to a melody that's so ugly by conventional standards. More than any other song on this album, this one proves that Yowie is certainly no one-trick pony. If they keep up making each consecutive album slightly more listener-friendly at their current tempo, I imagine they'll end up at their own Love Beach approximately in the year 2286, so don't give up hope, ye faint-of-heart music lovers! This band will eventually give you what you're looking for.

Speaking of evolution, one thing I find amusing about this band is the progression of their song titling habits, from Cryptooology's gibberish names with three syllables at most ("Towanda", "Talisha", etc.) to this album's overlong and nonsensical titles such as "The Reason Your House Is Haunted Can Be Found On This Microfiche". And while I'm meandering about the album's non-musical aspects: I think the album cover looks gorgeous and its intricate web-like pattern is a perfect analogy for the music found within, but to be fair, it's still surpassed in awesomeness by the cover of Cryptooology, which actually showed the Bigfoot-like creature from Australian folklore from which the band takes its name (yeah sorry, they're not actually named after Japanese gay porn).

In conclusion, while I think Damning With Faint Praise is more original and a more technically accomplished product, Synchromysticism is still an impressive achievement and has merits that shouldn't be overlooked. Listen to it here if you dare.

Best song: ABSURDLY INEFFECTIVE BARRICADE

0 notes

Photo

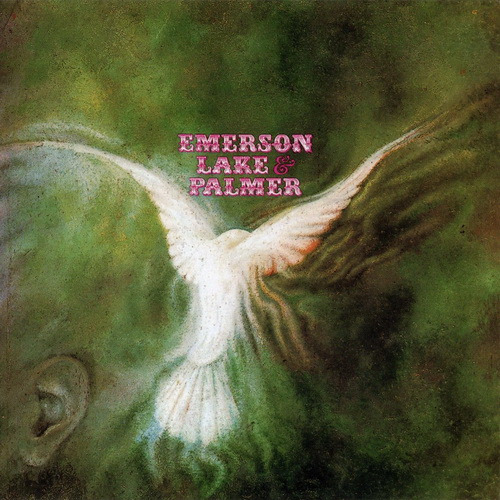

EMERSON, LAKE & PALMER - LOVE BEACH (1978): 4/10

Yeah! How do you like that album cover? What the hell happened? Okay, time for a little history lesson. Remember how the band used an orchestra on the previous two albums? Well, one day Keith said to the other guys: “Hey, wouldn’t it be a great idea if we took an orchestra with us on our next tour?” And… well, to be honest, it actually was a great idea. Artistically, at least. Backing up the old and the new ELP hits with orchestral arrangements resulted in some outstanding performances that were captured on the live album Works Live, which I heartily recommend to anyone who's interested in the band. Financially however, this was a really bad move. Paying the musicians and transporting their equipment was such a financial strain that the band would inevitably lose money unless they sold every last seat at every venue. And they didn’t succeed at that because the popularity of progressive rock as a whole took a nosedive in the late seventies. The genre's emphasis on complex rhythms and structures, esoteric concepts and instrumental virtuosity became more and more associated with snobbish elitism and was rejected by the new generation, which instead flocked to the more approachable, raw and rocking sound of punk rock bands such as the Sex Pistols, who regularly mocked progressive rock bands as part of their performances, with their famous “I hate Pink Floyd” t-shirts, and their burning of Yes and ELP records on stage. In addition, the music industry itself changed around this time and became far less receptive towards experimental music than it had been throughout the decade.

So, to make a long story short, ELP were in a bad spot in 1978, and were further plagued by deteriorating personal relations between the band members, as well as conflicts with the record company which demanded a hot-selling record. Love Beach was made in a desperate attempt to reach out to a new audience: it’s made up primarily of a bunch of lightweight pop songs but also throws in a few progressive-sounding tunes to please their old audience. The result, predictably, pleased no one at all and made ELP the laughing stock of the music world. Even the band members themselves have frequently mocked it. What else could they do? This album is just too easy to mock. Just look at it! Even the liner notes hardly say anything about the music and mostly just talk about how much fun the band had on the Bahamas, where the album was recorded.

I mean, you can tell that there are some creative problems when a singer has trouble trying to make the third line on an album fit within the meter. At the same time, Keith changes his synthesizer tones from otherwordly and ominous to sickly sweet and sappy, and Carl plays an awkward drumming part that never seems to get off the ground. And despite all of that, I still have to count “All I Want Is You” among the better songs on here, because it shows at least a wee bit of classical influence and of the old production style (and to be fair, this is hardly worse than Greg’s pop stuff on Works, Volume 1).

However, things very rapidly go off the deep end with the title track and “Taste Of My Love”, which are basically guitar-led cock rock anthems that have Greg singing oversexed smut that would make even Gene Simmons blush with embarrassment (Oh, I almost forgot: all of the lyrics on this album were written by Peter Sinfield, who originally rose to fame by supplying King Crimson with his hallucinatory texts about 21st century schizoid men and rusted chains of prison moons, and who just five years earlier thought up the apocalyptic machine warfare themes for Brain Salad Surgery. Now he writes such lovely slices of poetry like “I’m gonna love you like nobody ever loved you; Climb on my rocket and we’ll fly”). Anyway, these songs are far too tame instrumentation-wise to appeal to the general sleaze-rock crowd, and far too simplistic to not infuriate anyone expecting to hear the ELP of old: Keith’s synthesizer parts feel like they were added to these tracks more out of obligation rather than because they actually contributed something of substance to the music.

“The Gambler” goes for a comedic mood again, but really overstays its welcome with its generic female backing vocals as well as some shitty ukelele and some equally shitty harmonica to spice up the pill. Oh well, at least it has some funny keyboard playing. And "For You" ... well, that one's actually alright. Unlike the rest of the album, it's more melancholic and reflective than sappy and jolly, and it has some nice echoey guitar playing, too. I couldn't care less about the "rocking" coda though (in quotes because it just sounds kind of torpid).

In contrast to the first side of the LP, the second side holds tracks that are basically bones thrown toward the band's traditional audience. The first track on here, "Canario", is also not bad. It's another classical cover (of a piece by Joaquín Rodrigo) that still sounds overly sweet and kinda cheesy but at least it has some dang energy which is sorely missing on the rest of the album, particularly on the next track, where things get really murky when the boys try to pen one more epic multi-part suite in the old prog style, called “Memoirs Of An Officer And A Gentlemen”. Don’t expect another “Tarkus” here: this whole suite is just a big toss-off. Almost the whole thing is in the same key and the same plodding tempo, and it sticks to the same disgustingly cheerful atmosphere that dominates the rest of the album. Furthermore, the lyrics try to sound really grandiose and world-shattering but, when taking the utterly banal subject matter into account (a soldier falls in love with a nurse but oh no she died the end), just come off as pathetic. But worst of all, Keith's keyboard playing feels completely sterile and forced throughout the whole thing, and there's no impressive synth solo to hear for miles around. The final movement, "Honourable Company", is a gradually intensifying march that's obviously intended as a rewrite of "Aquatarkus", but it has no climax and just ends up sounding like really bad theme park music (I apologize if I overuse this analogy in my reviews but I really can't think of a better thing to compare it to. Do you remember waiting in line for an Indiana Jones ride and hearing some super-cheesy tune for the grand, magical adventure you're about to go on? Yeah, that's the one ). Not even the gratuitous Chopin quotations help bring the suite to life or anything resembling life.

Oh, I'm sorry. I must come across as angry right now, but honestly, the spectacular stupidity of this album makes it impossible to actually hate or get angered by. The incompatibility of Emerson, Lake & Palmer with their newly created popstar image, combined with the unconvincing manner in which they pursued this new direction, makes Love Beach one of the most hilariously ham-fisted and ill-conceived products in the history of mainstream rock music. So just don’t take it too seriously. Don’t look for quality here. Just let the stupid sink in and have a blast.

Allmusic's original review of this album consisted of just one sentence which read: "A record that ELP released only because they owed it to their original label, and that's all one needs to know." I suppose it’s a mystery whether the band just wanted to make a few dollars and please Atlantic Records or if they actually wanted to make a turn in this direction, but in any case, the album flopped both commercially and critically. Now reviled by their former fans and belittled by their enemies, the trio finally called it quits and went their separate ways.

Best song: eh, I guess it's probably CANARIO

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

An interview with Dani Lee Pearce

In 1992, when Frank Zappa was described by Nicolas Slonimsky as “the pioneer of the future millennium of music” because of his ground-breaking work with the Synclavier, one of the world's earliest digital audio workstations, Zappa immediately disavowed that title, convinced as he was that this technology would never catch on and would eventually go lost. Today, 25 years later, this way of composing and producing music is utilized by countless talented artists across the world, armed with nothing but a computer. One of the most exciting underground musicians who uses the technology that Zappa once helped popularize is Dani Lee Pearce. Since she started releasing music under her current name in January 2015, she has completed six albums covering a wide variety of genres, and is currently working on a seventh album. Her original album trilogy, consisting of the instrumental albums Dani Lee Pearce, Dépayse and Kelvin, was released in the first half of 2015 and combined elements of chiptune, progressive rock and experimental music. From then on, she has released a number of vocal albums that draw more inspiration from pop and folk music, starting with Notes Of A Nervous Little Pixie in March 2016 and following it up with Petrichor, which was released exactly one year ago today. Her most recent album, Dandilionheart, was originally released in February of this year and was later remastered and re-released in July. As a fan of her work, I was honored to have a chance to speak with Dani about her oeuvre and her plans for the future.

Let's start with a somewhat clichéd question: Which musical artists do you feel your latest three albums have been most influenced by?

It's quite difficult to narrow it down to just individual artists in a lot of respects. Music itself, in all the nuances and idioms it contains, tends to influence my work in at least one way or another. A lot of times I suggest or hint towards things that people probably wouldn't expect. Individual artists are there in some places, but I actually find it a lot more fun to have people try to guess what my music could be influenced from. Whatever gets guessed for a particular song is usually correct.

Can I make a guess?

Go ahead.

The continuous driving rhythm, slightly droney nature and stream-of-consciousness style vocals on the track "Dandilionheart" (or at least the first part of it) reminded me of Talking Heads. Am I far off?

Nope. Pretty much if you say "this reminds me of this" I will go "Yes" every time. I listen to music all the time of all genres and all of it gets worked into my psyche and inevitably comes out into the music somehow when I'm writing it. I may subconsciously be working in things I don't intend at any given time during the process.

From 2016’s Notes Of A Nervous Little Pixie onward, all of your albums have contained vocals. Is making vocal music something you had wanted to do ever since you started releasing music under the Dani Lee Pearce moniker, or did this desire come later?

Earlier than that, like, 2013 at least, back when I made music under the name Kansas City 7up. My earliest recorded attempt was a song I never finished called "The Midnight Seer" from 2014, but ultimately shyness and a lack of the right equipment prevented this from happening sooner. After Kelvin I made a solid pledge to myself that my next album would have me singing because it would add an important and essential element to my music, and any new music I made would be saved until I could get that to happen. That's part of why the gap of time between Kelvin and Nervous Little Pixie was as long as it was.

Which do you usually write first: a composition or lyrics?

That depends on what I think of first, although generally these days the words come first, in a rough form, since I will usually come up with things I want to say but not yet in any particular order how I want to say them. The music then helps me to establish a metric and pattern for how I will fit my vocals into the song in a way that works, which will in turn help me to revise the song and add things to it to make it gel. I try to work on each element independently because I like the challenge of creating music that surprises me in regards to the words I'm writing it for. Some of the things I've been working on recently are like that. It very much helps to keep my music fresh and unique to me. By contrast, all of my current albums were mostly music first, words second. Some songs took years to write proper words to, like "Tell Me I'm Cute Again Cause I Forgot", which previously existed with 3 different sets of lyrics before I finally settled on the current set. It's a more difficult way of working now but I will occasionally still try making a song that way for fun, since it enables some great creativity.

I'd like to talk about your album Petrichor, which is approaching its first birthday at the time of this interview: When you created the album, did you set out to make a concept album from the start, or was it an idea that came into play while you were working on it?

The album came in many embryonic forms when I was first developing it. At first it was going to be an album called The Many Lives of Maypole, and it was going to document the life of a young girl with queer parents and her friendship with a child who later comes out as trans who has much more angry conservative parents. I was going to write a book in addition to an album of music to go along with it, and while only one song ever came out of this incarnation, the idea of an album + accompanying book stayed, and I later wrote "🌙🌙🌙", which I haven't gotten to publishing yet, to go along with Petrichor, containing poetry that elaborated upon the concepts of that album.

After Maypole it was then called The Giving Of Violets, an album which would have been about a capitalism-induced apocalypse that forces society to start over on a much better path, this time fully embracing LGBT rights among other things, as people are now more free to explore their identities gender and sex wise. The title is derived from a lesbian custom in the 50s where women would give each other violets to declare their love for one another, which in the story would be readopted as a gesture of affection. A good chunk of what would eventually be the finished album was written during this time, with early versions of "From Young Unknowing Eyes" "I Hope It Doesn't Rain" "Silver Tree’s Mixtress", "Twig Parade" and "Lute-Bird Calls" being put down in a test sequence, along with "Down In Evergreene", which was already done, and what eventually became "Give You My Earth" on Dandilionheart.

Some time later I had an anxiety-induced epiphany and spent a period of time very withdrawn in a quiet space only listening to quiet music, and I thought of an idea for an album of "whispersongs", very quiet music with whispered spoken word of very simple poems accompanying it. The project would have been called Rest Easy Love, and that's where I came up with "This Tree". This was the beginning of me writing poetry for a period of time, which eventually led to the writing of "Over My Wall" and "The Hill of Mist" as well. The Giving of Violets was dropped since I felt I could make the concept stronger, and later an album called The Scarlet Sky With Anais was developed but never fully finished. The song that eventually became "Monsters and Rainclouds" was listed as the final song of an album that also contained songs that would later become "Periwinkle Death", "Tell Me I'm Cute Again Cause I Forgot" and "Burning Pearls". "Down in Evergreene" was listed again also.

The actual concept began to develop around this time when I met three very important people: The first was a musician named Izzy Unger Weiss who met me for the first time at a birthday picnic, and the first thing we ever did together was sit down and play guitar. They introduced me to more worldly sensibilities both in their music and aesthetic, which began in me a more forthright interest in what I like to call "personal occult", which is essentially like a redefining of monsters, demons, spirituality, magic, the construction of the universe, etc. all on one's own terms, either casually or otherwise. Izzy did that to an extent, at least I could sense it, I'm not entirely sure if she would say the same but that's largely what my brain tends to produce for answers regarding it. Izzy was also overall a big musical influence at the time and made me more interested in learning guitar and writing guitar-based music. I'd later design a couple of album covers for her own music and eventually we may even collaborate on something.

The second person I met was Never Angel North, an agender independent author who was and still is writing an anthology of fiction collectively titled Sea-Witch. At that time the first volume was written but not yet released. Never's writing is unlike anything that's really been written in regards to fiction or poetry, especially in a queer/trans context, as it constructs an entire world inside of a living, breathing, feeling sea monster and the inhabitants who worship a meteor to whom they pray "may she lay us waste". The writing is at once emotional, intimate, sexual, terrifying, harrowing, ecstatic, decadent and mordant, but in all respects is absolutely brilliant and it completely redefines ones view of the world, of life, of gender, of quite possibly everything. It was being introduced to Never's writing and Never hirself that I became more open to the idea of constructing a world of my own in a similar fashion.

The third person, Jade Eklund, I met through Never, and she showed me through her own art how I could make this possible. Here was someone who practically lived and breathed their art which largely revolved around spiders and a recurring central character known as the Spider Queen. You'd enter her room and the walls would be covered in drawings ranging from spiders to seeing eyes to otherworldly presences, and she had filled out several notebooks of things that she had written stream-of-consciousness, and continued to build upon her mythology by doing the same on Facebook. We traded notebooks the first couple times we saw each other to get to know each other a bit, and she would draw/write surreal things in my notebook that inevitably influenced Petrichor's content, specifically the character of YESSAND the Masquerader King. I began writing poetry and concepts stream-of-consciousness in my own right, making up my own mythology taking inspiration from all three of these people and making frequent references to them in the process as I did so. This carried over into the eventual songwriting of Petrichor, and the creation and completion of the remaining songs.

"Monsters and Rainclouds" was at one point a song written specifically for Never, referencing a lot of elements of hir writing, and snippets of things Jade wrote in my notebook, which contained unfinished lyrics for Petrichor's songs, found their way into "Masqueraders" and the background voices of "Lute-Bird Calls".

Well damn, I was planning to ask some more follow-up questions about the story, the role of Jade Eklund (whom you credited in the album's description on Bandcamp) and even the voice samples on "Lute-Bird Calls", but you've already answered everything I could ask about the album. I'll be sure to look into the works of the other artists you mentioned just now.

I’d like to talk about your latest album now: Dandilionheart. In contrast to Petrichor, which is an epic, prog-like concept album, Dandilionheart is a collection of avant-garde pop songs that seem to be only loosely connected thematically, much like Notes Of A Nervous Little Pixie. Was it a relief to be able to write self-contained songs again or is it actually easier for you to write music when you have an overarching concept to work within?

Concepts are actually quite difficult because you become restrained within one world of thought, and if you want to make it work you can't stray too far from it. Petrichor is a satisfying work but it was stressful to have to write about one thing for 8 months. Some of Dandilionheart's songs I actually began writing in tandem with that album, just to give me another outlet for other ideas at the time. So I would say that yes, I actually have more fun with individual songs than anything else, and I will probably continue writing in that context. I'm someone whose mind always wanders to different places at different times, so it's important for me to have a variety of ideas going because it feels more free to me. In that respect Dandilionheart was quite nice to make.

There’s another difference I’ve noticed between the two albums: On Petrichor, the vocals are quiet and dreamlike throughout, whereas on Dandilionheart they have a more prominent and more powerful presence. Is this the result of a conscious decision or simply a natural consequence of you becoming more confident about using your voice and getting more familiar with the recording process, et cetera?

I was very confident with my voice when it came around to Dandilionheart and in a lot of places I get really into the song and just let loose, try things with it that I hadn't tried before. "Let Me Remind You" is currently home to the highest note I've ever sung for example. In some ways it is conscious as well because I always try to make albums independent from each other, like making films without visuals. I largely let the music decide what my voice will do though, and the music was definitely a departure. The fact that I actually sing loud is another indicator, I had never really done that before this album.

Let’s go back once more to the 13-minute title track of Dandilionheart. As you can probably tell I'm intrigued by the process by which specific music gets developed, and if I’m correct, “Dandilionheart” (the song) is the longest track out of your latest musical trilogy. Did you set out to create a track of such length before writing it, or did it naturally evolve into what it ended up being?

The project file name for the song is "something maybe", which indicates that when I started this I didn't even know if it was going to turn into anything substantial. I was largely at the time playing around with the sample from what became the end of "Galaxy Owl" just to see for fun if I could take it anywhere and the more I developed the piece the more it kind of took on a life of its own. Specifically the section right before the lyrics was when I got the first inkling that the song would become what it ended up becoming. I realized three minutes in that it sounded thematically linked to a composition I had written in 2013, so I ended up stringing that (the "let all the rain come down" section) together along with another composition I had written in Sept. 2016 (the "goddexx bless" section) on the basis that they all shared a similar drive and tempo. When I got them all together and listened to it back I was dumbfounded at how perfect all the pieces sounded together, and then I had my song. I knew it was special and I knew I had to make it the title track from then on, and the lyrics were later written to fit the best I could with the sound.

Do most of your songs come into existence through something along the lines of what you just described?

Sometimes, yes. "Masqueraders" happened the same way only with one additional section. I don't think I've quite written anything else in exactly this way, but I do still find uses for old unused compositions I have lying around.

What is the biggest challenge you encounter when composing music?

I don't really face any incredibly big challenges in the composing bit itself except for sometimes finding uses for a composition, because sometimes I will write something but not have any particular idea what to do with it yet. I think my biggest challenges actually come in producing/mixing a track properly, which I am always very persnickety about.

I think also, at least today, it's trying to figure out how I want to do a song that I have lyrics written for. The number of approaches I could take is very broad and it's hard to find a direction that I think fits my words the best. I'm dealing with that situation presently for one song.

I think you've told me in 2015 that your first three albums were made primarily using FL Studio. Do you still use this or have you switched to a different workstation in the mean time?

Dani Lee Pearce was actually also partially made with Ableton Pro when I was in college ("You For You Four Ich", "Every Clock Is 3 Minutes Behind"), and with a Casio Keyboard ("Animated Tattoo"). Otherwise yes, FL Studio is still my weapon of choice. At this point I visualize my songs as project files within that DAW and can make an instrumental up in under an hour at times. I don't anticipate that I'll change from it at any time soon since I'm so familiar with it and can work with it so efficiently.

Like you said, in your original album trilogy from 2015, there were a few tracks that were played on a keyboard, and “Moth Girl” was originally recorded on acoustic guitar but was later rerecorded using a DAW when you reissued your latest album. Do you still use any physical instruments in your recordings, and/or do you plan on using physical instruments in the future?

Of my yet-to-be-released work I have one song that does in fact have me playing guitar, and another song in which I have had someone record guitar for me. One of my girlfriends is also going to be contributing guitar to my music eventually, and at some point I plan to record myself playing clarinet for some songs, as that is the one instrument I have proficiency at.

Is there anything else you’re willing to disclose about what we can expect from you in the future?

More surprises. And more ways to convey them.

I can’t wait.

I’m nearing the end of my question list now. Can you recommend to anyone who reads this interview two artists who deserve far more attention than they’re getting right now?

Rumor Milk is a very good musician friend of mine from Canada who gets very little attention for her work but she has a voice that has made me well up in tears multiple times. She is very talented and it would mean the world to her if more folks would check out and support her music. Chase Milo Reid is one of the first trans musicians I ever met when I came to Portland homeless and I've watched him perform live and develop as a talent in amazing ways. He's another who I think is worth people's attention and he would also very much appreciate additional support.

Finally, if you’ll allow me to ask one more clichéd question: what advice would you give to other aspiring musicians?

Don't listen to advice intended for aspiring musicians given by musicians who are no longer aspiring. Let your soul do the talking. Let it dig into itself and find what makes it you, and turn that into art. Allow yourself to be raw and wild. Change it however you wish. Don't change it at all. However you do it, just make something, anything. And most importantly, make a fucking shitload of it.

Thanks immensely for your time; I've thoroughly enjoyed this interview. I'll be sure to check out all the artists you brought up and I'll be sure to use the word "persnickety" as much as possible now that I've been introduced to it.

I've very much enjoyed doing this! Thank you very much for your interest in me, it helps me to remember that I'm doing something that reaches people.

_____

Dani’s music can be found here and here. You can read my review of Petrichor here.

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

DANI LEE PEARCE - PETRICHOR (2016): 9/10

Who's ready for a blast from the past? The first article I ever wrote for this cute little album review series was one about the self-titled debut album by Dani Lee Pearce, which I published exactly one year after the album's release. At the time I felt compelled to write a review out of disappointment with the lack of attention for an album whose intelligently written and produced music intrigued and inspired me. Therefore, I believe it's appropriate to repeat this principle now, a year and a half later, writing a review for Ms. Pearce's fifth album, which was released on the 8th of November 2016 and which has brought me even more joy, inspiration and endearment.

The last time we saw Dani Lee Pearce on this blog was in 2016, when only three albums credited to her name had been released. Her debut album, which I covered at the time, was a collection of proggy instrumentals in a chiptune-ish environment. Petrichor, released a year and a half after her debut, was still produced entirely by digital means (except for the vocals) but certainly cannot be called electronica by its normal definition. The chiptune and synthpop elements are now mostly gone, and although synth- and other keyboard-like instruments still dominate the sound, the instrumentation on this album notably adheres more to rock conventions, with sampled guitars, percussion, strings and woodwinds, and of course Pearce's vocals, which have been featured prominently on all of her albums from 2016 onward. The music instead takes more influence from folk rock and dream pop and overall sets up a gentle, pastoral mood. The songs themselves are also more traditionally structured, with more recognizable verses and choruses, and aren't based on very fast or unusual rhythms.

On the other hand, the harmonies are still lovably eccentric and still reveal Dani Lee Pearce's idiosyncrasy, and most of the melodies are very catchy. And here's a fact that ought to please any fan of progressive rock (as well as discourage anyone who's thinking about accusing the artist of "selling out"): Petrichor is a 90-minute long concept album centred around an epic storyline with fantasy and science fiction themes. This story isn't too keen on revealing itself: the description on Bandcamp is quite convoluted and uses a lot of obscure jargon, while the lyrics are generally cryptic and leave a lot open to personal interpretation. To the best of my understanding, the story is a series of vignettes that together paint a picture of a mystical fantasy world, the people that inhabit it and the conflicts that take place in it. In any case, the lyrics themselves are well-written and don’t resort to clichés, and they’re sung in a dreamlike, almost whispering tone that fits both the music and the images being described. The only exception to this vocal style is “Masqueraders”, a hilarious tune which I can only assume to be dedicated to a group of space pirates and which is sung in a fittingly malicious manner (I especially like the first couple of verses, which reveal that the Masqueraders in question are pirates in more than one meaning of the word).

The other vocal tracks in the first half of the album range from passable to stunning. The album opens with "... And The Leaves That Fell That Day There", a folkish ballad that's dominated by samples of chimes and acoustic guitars and features a nice instrumental bridge featuring an electronic string orchestra. "I Am The Sand Girl" is a delightfully catchy pop song with a quiet, soothing coda ("This Tree"). "Over My Wall" is a really strange but also really cool little tune with an odd melody and a singing performance that slowly devolves into arrhythmic mumbling throughout the song's duration. That just leaves "From Young Unknowing Eyes", an organ- and glockenspiel-led ballad with a not too interesting chord progression, as the only track in this category that just sort of passes by unnoticed whenever I listen to the album.

However, the track that makes this first half shine most of all is an instrumental: “Purity And Disarray”. The melancholic chord progression, the distant-sounding Mellotron-like strings and the distorted, slightly detuned electric piano melody together create an impression of wandering alone lost in space, endlessly searching for something that can't be found. Two other instrumentals ("The Ember Leaf" and "The Lone Survivor") are more straight-forward and not as memorable but still good.

Now, while “Purity And Disarray” is probably my single favourite track on the album, I actually think the album’s second half is more consistent than the first overall. The only track on it that does nothing for me is “The Hill Of Mist”, which is little more than a lengthy ambient soundscape accompanied by electronically altered voices (although the lyrics, which seem to describe a euthanasia ritual, might be the most beautiful on the album). The tracks that surround it are excellent: "Down In Evergreene", the album's lead single, is another beautiful folk ballad and "Where The Ashes Go" is a wonderful ethereal instrumental with a koto sample as its lead instrument. The next track, "I Hope It Doesn't Rain When I See You Today" puzzles me to no end. It's a dreamy, lullaby-like tune that's really overly sweet and sentimental, yet it somehow works and is genuinely moving. For me, at least. Call it a guilty pleasure if you want.

From this point onward in the album, the story seems to focus around one specific character and set of occurrences, which makes all of the remaining tracks directly connected to each other thematically, and, appropriately, they all segue into each other as well. This suite (if you will) seems to be the album's pièce de résistance. We first get three more proggy instrumentals: the solemn, organ-led "Silver Tree's Mixtress", the playful "Candy Necklaces", and the cheery, optimistic "Twig Parade". This is followed by "Lute-Bird Calls", which is technically instrumental but features samples of people talking and reciting poetry excerpts, so I guess the proper term would be semi-instrumental? In any case, the song is little more than a melody being repeated over and over again, but the excellent production, the multiple melodic trinkets and background instruments and the dreamy, reverby vocals help bring the already great melody to life and create a truly beautiful atmosphere. Finally, the majestic, dream-poppy "Monsters And Rainclouds" serves as a climactic showstopper before the brief "Cast Your Sleep Spell" closes the album with the same chime noises that it started with.

The individual songs on Petrichor are strong enough, but listening to the album in its entirety has a strange effect on me that's hard to put into words. The progression of the story corresponds perfectly with the way in which the music has been ordered and paced, and together creates the feeling of a journey: After listening to the full album, thinking back to the first track feels similar to thinking about the moment you got up in the morning before you went on a long travel by plane or car. Off the top of my head, the only other albums I can think of that give me the same feeling are Genesis’s The Lamb Lies Down On Broadway and National Health’s debut album. It's an album that makes you feel like something meaningful was accomplished by the end, and if you take it in as a whole you too can hopefully overlook the few weak spots that are bound to appear on an album of this length, and be enchanted by the magic of the music and the world it's created.

Best song: “PURITY” AND “DISARRAY”

Listen to the album here. Seriously.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

EMERSON, LAKE & PALMER - WORKS, VOLUME 2 (1977): 6/10

(Originally posted on 17 October, 2017)

The second Works album (released eight months after the first one) is really strange. It feels even less like a coherent whole than its predecessor, because Works, Volume 2 is less a real album and more a collection of outtakes. Most of the tracks on this record feel like they could have fit in perfectly on Works, Volume 1 and were even recorded at the same time but didn’t make the cut (presumably because they ran out of disc space with that one). Other tracks even hail back to the sessions for Brain Salad Surgery, including a track called… “Brain Salad Surgery”. Finally, “Barrelhouse Shakedown” and “I Believe In Father Christmas” had previously been released as solo singles by Keith and Greg, respectively, and appear here without any alterations. For this reason, Works, Volume 2 is often dismissed as a throwaway or stop-gap album, but while I think it’s certainly quite pedestrian compared to ELP’s earlier work, I still think such a classification is unfair. Like Volume 1, this album is just a mixed bag of moments that are bound to bore you and moments that are worth your time (many of which even exceed most of Volume 1 in beauty).

This album isn’t strictly divided into separate parts for each band member but most of the tracks still feel like they’re courtesy of one specific musician rather than the band as a whole. For example: “Watching Over You” and the aforementioned “I Believe In Father Christmas” are clearly Greg’s songs: both are relatively straight-forward pop numbers, but they're actually better than what he put on Works, Volume 1: they’re less dragged out and they’re a lot more sparsely arranged, which actually helps make them seem more authentic (at least in comparison to the bombastic, out-of-place orchestral arrangements which made the banal pop stuff like “Lend Your Love To Me Tonight” seem all the more pathetic). “Watching Over You” is basically just a gentle acoustic guitar ballad; certainly no “From The Beginning”, but still good enough and not pretending to be more than what it is.

“Bullfrog” and “Close But Not Touching” were written by Carl and follow the same big band jazz style as on “Food For Your Soul” from the last album. Both take influence from military march tunes, with “Bullfrog” sporting a snare-heavy main theme with a catchy main melody played by Carl himself on the marimba, and “Close But Not Touching” opening and closing with a Yankee Doodle-like flute theme. Carl also hands a solo spot to his fellow band members on both tracks: Greg plays a mad guitar solo on “Close But Not Touching”, and on “Bullfrog” Keith plays a synth solo with the same steel drum-like tone as on “Karn Evil 9”.

Now, Keith is the only one whose contributions here differ notably from those on the last album: There’s no classical music here. Instead, he plays a bunch of cute ragtime tributes on honky-tonk piano with a brass section backing him up, including a cover of Meade Lux Lewis’s “Honky Tonk Train Blues” and his own “Barrelhouse Shakedown”. Finally, he plays a really nice version of “Show Me The Way To Go Home”, another hit song from the 1920s (which you may recognize from the movie Jaws), although Greg manages to steal the show on that one with a lovely vocal performance.

All of the remaining songs do feature the boys working more together as a group, but this time there’s not that much to say about them, so it’s like a complete reversal of Volume 1. Out of the songs taken from the 1973 sessions, “When The Apple Blossoms Bloom In The Blah Blah Of Your Bleepity Bloop” is just a pointless jam, while “Brain Salad Surgery” is pretty funny, though probably a little too inessential to be featured on the album which was named after it. But all of the other tracks are completely forgettable: some generic blues stuff, an orchestral version of “Maple Leaf Rag” (why?)… Let me just end by saying that if you want to see a completely different side of these musicians, you might find this album quite interesting and enjoyable, but if you want to hear more grandiose prog in the vein of “Tarkus” or “Karn Evil 9”, don't bother with this album because it doesn’t have what you’re looking for.

Although the Works albums aren’t bad, they clearly present a band in crisis: a band that can no longer agree on a unified vision or direction, but also cannot manage to truly excel in the new directions pursued by the individual band members. And as much as it pains me to admit it, these two albums may also illustrate the inherent limitations of Emerson, Lake & Palmer as a unit. When you think about it, all of the previous studio albums followed a certain formula: a number of (usually lengthy) prog epics with emphasis on synths and organs, along with some rocky adaptations of classical compositions and at least one introspective Greg Lake ballad. That’s not to say of course that they didn’t make truly great music within this formula; Brain Salad Surgery arguably marked the perfection of the formula. However, the moment when the band tried to escape from this formula was the moment when they set their own downfall in motion. ELP would only go downhill from here on, as was painfully evidenced by their notorious follow-up album which I’ll hopefully discuss soon. Prepare for a riot.

Best song: a tough call but it’s probably BULLFROG

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

EMERSON, LAKE & PALMER - WORKS, VOLUME 1 (1977): 6/10

(Originally posted on 17 October, 2017)

Knowing that a masterpiece such as Brain Salad Surgery would be hard to top, Emerson, Lake & Palmer wisely decided to go on a hiatus for four years before making a grand, unexpected comeback in 1977 by putting out two albums simply entitled “Works, Volume 1” and “Works, Volume 2”. These albums did not exactly meet public expectations, to say the least, and were met with befuddlement more than anything else. So let's get befuddled together and dive right into them. The first of these opuses is a double album, with three LP sides that are dedicated to solo works by each band member, and one final side featuring the band as a group. It’s a wacky collection for sure, but it’s also very incoherent and, sadly, just not very exciting most of the time.

Emerson’s side is entirely occupied by a fully classical piece for piano and orchestra (the London Philharmonic, in case you’re interested), simply titled “Piano Concerto No. 1”, and I have very mixed feelings about this concerto. When I first found this album in 2012, I was thoroughly impressed with the band’s courage and unwillingness to compromise that allowed an album featuring an 18-minute classical piece to be published by a major rock music label. Even now I think it’s hilarious to have a track called “Piano Concerto No. 1” on a rock album. I also have to credit the concerto for being one of the musical pieces that opened me up to classical music as a whole. However, now that I’m looking back on it with more knowledge of classical music, I must say that the composition itself is really nothing special. It’s got a few tasty parts, such as the opening fugue and the more aggressive segments in the final movement that somewhat resemble Stravinsky’s early ballets, but the majority of it just plods along through a quasi-pleasant atmosphere with no interesting melodies, harmonies or rhythms in sight. Hell, even the piano playing isn’t that impressive most of the time. Some parts of this sound like the background music you might hear while walking through Disneyworld. Fun fact: Keith originally wanted Leonard Bernstein to conduct the orchestra on this track, but Bernstein refused because he thought the composition was too primitive. Ouch.

Greg Lake’s side is definitely worse, though. It seems like Greg was already getting tired of working within the band as the songs he contributed to this album try to create an image of him as a pop/soft rock superstar, but frankly, they’re all pretty mediocre, and if they didn’t feature Lake’s voice, I wouldn’t know what to praise them for. They all sound very cheesy, but not really in a funny way. There are some standard love songs (“Lend Your Love To Me Tonight”, “Nobody Loves You Like I Do”), some stuff that goes for a more melancholic vibe (“C’est La Vie”), but it’s all just way too generic to be truly enjoyed. “Hallowed Be Thy Name” almost stands out due to Lake’s slightly more aggressive delivery as well as the cautiously dissonant orchestral backing, but it still doesn’t make up for crap like “Closer To Believing”, which sounds like the intro theme to a bad 1950s sitcom. What is it even doing here? Leave overblown gospel anthems to Peter Gabriel please, Mr. Lake; he can write them a lot better than you.

Thankfully, the second disc is a lot better. For starters, Carl Palmer’s side is probably the most listenable of the solo sides. There are a few more classical adaptations here, but it’s mostly dedicated to a number of jazz jams: “L.A. Nights” and “New Orleans” are clearly rock- and blues-inspired (and even feature Eagles guitarist Joe Walsh) while “Food For Your Soul” is more influenced by big band music. They’re not terribly exciting but at least fun to listen to (even though “L.A. Nights” slightly overstays its welcome). “The Enemy God Dances With The Black Spirits” is better, but that’s mostly courtesy of the orchestra rocking out to what is basically an unaltered Prokofiev composition with some drums added on top. There’s also a cool orchestral version of “Tank” from ELP’s first album, which for some odd reason omits the drum solo (it’s got a nice oboe solo, though). Come to think of it, even though Carl’s drums are mixed quite loudly throughout his contributions to this album, he doesn’t really plays solos here, except for a couple of brief spots in “Food For Your Soul” and his (pretty dispensable) pitched percussion arrangement of a Bach piece (“Two Part Invention In D Minor”).

So it’s no surprise then that the ‘group side’ is, overall, the most accomplished part of the album. Out of all songs on Works, Volume 1, “Fanfare For The Common Man” comes the closest to recreating ELP’s old style. Aaron Copland’s composition of the same name is here turned into two fast, bouncy, catchy themes that bookend another absolutely furious synth solo by Keith on his newly acquired Yamaha GX-1. As for the lengthy “Pirates”, I think it’s only a partial success. First of all, I think it’s admirable how well the band managed to combine the orchestra and the rock band in a perfect synthesis. However, the composition itself is split about evenly between exciting parts and parts that just sound a bit dumb. While not as bad as on Emerson’s Piano Concerto, the orchestration on here, for a large part, still sticks to the cheesy generic ‘Hollywood’ style, so that it’s hard for me to listen to this without imagining some corny water show about pirates in a large theme park. Then again, maybe that was the intent? I mean, the lyrics sure seem to treat the whole pirate concept as a joke, but then on top of that you have this epic sprawling classical/rock fusion happening. I really don’t know what the intent was here and I doubt the band knew either, but whatever. A for effort, guys.

So anyway, while I’d say the positive moments on Works, Volume 1 overall outweigh the negative ones (seriously, listen to that Fanfare), it just doesn’t make for a very good listening experience when you try to absorb it all in one go. I mean, I like albums that incorporate vastly divergent styles and genres, but I do want the quality of the music to be consistent, at least!

Best song: FANFARE FOR THE COMMON MAN

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

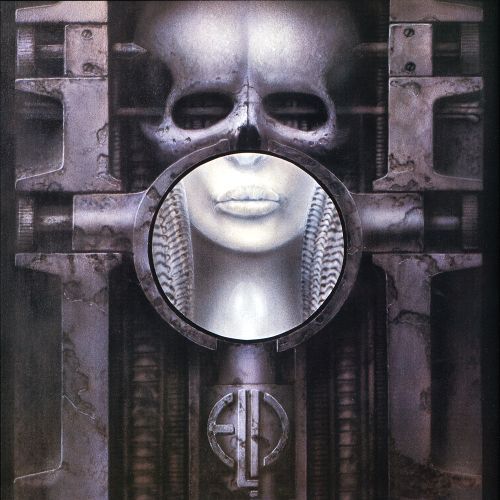

EMERSON, LAKE & PALMER - BRAIN SALAD SURGERY (1973): 10/10 (A rating I reserve for truly outstanding albums)

(Originally posted on 3 September, 2017)

Now this is better! Brain Salad Surgery more or less adheres to the same pattern as Tarkus, with an epic, prolonged centrepiece backed up by a number of shorter songs. Only this time it is a far more consistent product with virtually no weak spots at all, and the band has also gained a better understanding and handling of both their instruments and the capabilities of recording in a studio.

The opening track, “Jerusalem” illustrates the shift in tone perfectly: it’s a bombastic album opener that’s meant to kick things off in the same way as “The Endless Enigma” on the last album, but it’s more concise, more fast-paced and lively (in contrast to the snail’s tempo at which “The Endless Enigma” crawls along) and, most notably, far better produced: the organs sound a lot sharper and militant (the result of numerous overdubs) and, most importantly, the synthesizer has at long last settled comfortably in its role as lead instrument: instead of being used exclusively as a flashy novel solo instrument, it is here allowed to enhance and spice up the beautiful main melody. The classical composition on which “Jerusalem” is based (a choral song by Hubert Parry) pretty much sounds like what the band was trying to imitate when they recorded “The Endless Enigma” so I suppose it’s only fair that they’d put the original in the spotlight as well.

“Jerusalem” is followed by “Toccata”, another classical adaptation, though you probably wouldn’t immediately guess because of the track’s high-tech and electronic feel. Once again, Keith is the main star. Carl gets to rock out on his timpanis and tubular bells and Greg is even allowed some muted electric guitar playing in the quiet middle section, but for the most part it’s a merciless onslaught of keyboard manoeuvres set to a complex martial rhythm, with the organ providing an ominous background to the aggressive synth playing on top of it. At one point the track even breaks down to show off Carl’s set of electronic percussion, producing sounds such as police sirens and other synthesized noises.

Well, that one may be a little too over the top. Luckily, the two tracks that follow serve as a peaceful intermission after that little bout of musical insanity, and while they’re not as essential as the rest of the album, they’re still worth the price of admission. “Still… You Turn Me On” is this album’s Greg Lake ballad; probably not his best but still very soothing. Keith plays some lovely accordion on it, too. And “Benny The Bouncer”, the first in a series of ragtime tributes by Keith, has to be one of the most hilarious tracks these guys ever made, with Greg singing a silly tale of a bar brawl in a fake cockney accent along with muted drums and, of course, some excellent honky-tonk soloing.

But no matter how good these songs are, they still feel like afterthoughts when compared to the album’s pièce de résistance, which is the lengthy “Karn Evil 9” suite: a half hour-long composition, divided into three “impressions” (one of which is further divided into two parts), describing an apocalyptic scenario of a dystopian futuristic society being destroyed by a war between humans and machines (that’s something else I should mention: the lyrics on this album are actually competent [though that’s not that much of a surprise since they’re now written by former King Crimson lyricist Peter Sinfield rather than the band members themselves]. They convey the fantastic, intriguing images you’d expect from such a grandiose concept quite well, and steer clear of the embarrassing clichés that plagued the band’s earlier lyrical efforts. It still comes close to word salad [perhaps even brain salad] at times, but it’s imaginative word salad). To even begin listening to this monster must be a daunting prospect for any… Nah, who am I kidding? If you’re crazy enough to still be reading these reviews you must be crazy enough to derive some enjoyment from this.

The first impression (which was originally split into two parts in order to make it fit on the LP) starts off as a fast, determined, organ-dominated tune lamenting the soullessness and the mechanization of the fictional world, before turning into an even faster tune which is styled like a series of circus announcements, showcasing items from past societies that were lost and mocking the technological accomplishments of the future. The second part of the impression begins with the famous “Welcome back my friends to the show that never ends”, which is followed by one the most badass organ solos in Keith’s career (if you want to be impressed further, look up a video of a live performance of this song: while Greg is having fun on his electric guitar during this part, Keith plays the bass track on his synthesizer while simultaneously soloing on his organ with his other hand).

The second impression is instrumental, and is mostly centred around Keith’s keyboard playing again. For once, he goes back to his old trusted Steinway piano, leaving his organ completely untouched and only using his synthesizer to imitate a steel drum in a jam-portion of the song. The piano parts together constitute one of the most intricate and demanding compositions Keith ever wrote, going from a very fast-paced part to a slow, brooding, ominous section which gradually grows more ferocious before leading to a restatement of the opening theme, and finally into the synth-heavy third impression, a threatening march-like tune depicting the man-machine war.

The funny thing is, from a purely compositional viewpoint, many parts of this album aren’t even that much of a step up from Trilogy. I’ve thought hard and long about why exactly Brain Salad Surgery fills me with so much more satisfaction than its predecessor, but I’ve finally concluded that the production is really the one aspect in which Brain Salad Surgery truly shines, and which sets it apart from the band’s earlier efforts. The boys really put care into creating a diverse set of arrangements and different sounds for this album: the orchestral percussion on “Toccata”, the accordion and harpsichord on “Still… You Turn Me On”, the piano solo in the middle of “Karn Evil 9”, even the synth tones are far more diverse and fresh in comparison to Trilogy. And the songs themselves are more intricately layered and made up of far more separate tracks, too. I discover something new with each consecutive listen. Something I noticed only recently is the 1920s-esque piano which is hidden in the background of the first impression of “Karn Evil 9” and kicks in once Greg Lake sings about “Alexander’s ragtime band”. I love albums that keep surprising me no matter how many times I listen to them. Brain Salad Surgery has an admirable number of surprises up its sleeve, and I hope it can surprise me for many years to come.

Best song: KARN EVIL 9

1 note

·

View note

Photo

FUSE - STUDIO (2016): 8/10

(Originally posted on 2 August, 2017)

Fuse is not really a band, but a “musical collective” from the Netherlands consisting of two violinists, a violist, a cellist, a double bassist and a percussionist (Respectively: Emma van der Schalie, Julia Philippens, Adriaan Breunis, Mascha van Nieuwkerk, Tobias Nijboer & Daniel van Dalen). Essentially, they’re a small chamber orchestra. They’ve had some TV performances and enjoy very modest recognition in their home country, but are virtually unknown outside of it. A shame, because their debut album, Studio, recorded (indeed inside a studio) and released just a year ago, is really noteworthy and offers something of interest for a lot of different people.

True to their name, Fuse fuses a lot of different genres. This album runs the gamut from classical music to minimalism to jazz to folk music to country and even contains a dash of progressive rock. And despite the obvious classical background and training of the musicians involved, they are knowledgeable and respectful towards the musical disciplines they touch, and manage to throw in some jazz- and rock-style improvisations and solos in the mix for everyone to nudge their posterior to. Most of the songs on this album are covers, and the other songs were written by composers who were specifically commissioned by the band… or ensemble, whatever. But while there sadly may not be a skilled composer among the musicians themselves, they sure manage to show us what they are good at on this album.

The album starts off… Well, kinda drab. We first get a cover of Nils Frahm’s “Hammers”, slowed down to make it sound like a standard classical mourning piece, but it goes on for a little too long, and the composition on its own is just not very strong and loses its magic without the speed and the timbre of Frahm’s original. But really, this opening track is just not representative of what the rest of the album sounds like. There are a few more slow tracks based on solo piano pieces, some classical (Shostakovich’s “Prelude 10”) and others more jazzy (“Matthew’s Piano Book 9”), but they’re not very long and they aren’t what makes this album stand out.

The meat of Studio are the more energetic tracks, heralded by the group’s take on Dave Brubeck’s “Blue Rondo À La Turk”; one of the best versions of that song I’ve heard, and I’ve heard a lot of different versions. Structurally, it’s quite close to Brubeck’s original, but it also takes a page from the famous version by the Nice, in that it adds its own flair of rock-like extravagance and energy. Violinist Julia Philippens rocks the house down during the song’s jam section, and the Eastern European folk-inspired intro and ending sections (added specifically for this version) are a delight. This folky vibe can also be heard on the cover of Frank Zappa’s “Echidna’s Arf”, a song notorious for being particularly difficult to play even by Zappa’s standards, but the musicians magnificently work their way through the song’s many different movements.

The album doesn’t let up after that either, and after the aforementioned Shostakovich cover, which serves as a quiet interlude, comes the group’s country homage “Attaboy” (a jolly good song, I say, and I’m not even a fan of most country music). This is followed by Mikrokosmos 149 (a piano piece by Béla Bartók that is here turned into a jazz jam complete with a double bass solo by Tobias Nijboer), the more subdued “Vector”, and finally “Mister Black”, which features some badass cello solo spots by Mascha van Nieuwkerk, and an even more badass violin solo by Philippens, during which she hooks up her instrument to a wah-wah pedal (the album’s sole moment of electric amplification).

The album ends with “Recitative À La Baroque”, which is pretty short and almost unnoticeable. It feels more like an epilogue than an appropriate ending to the album. So again, it doesn’t give a good representation of the rest of the album, but at least you’ll already have had the chance to enjoy the rest of it when you hear it.

I just realized that this is one of only two reviews I've written for this site of albums whose authors are still active, so I should probably leave a link to their site and more specifically to the page that features some links to where you can buy or listen to this album. You're welcome.

Best song: BLUE RONDO À LA TURK

0 notes

Photo

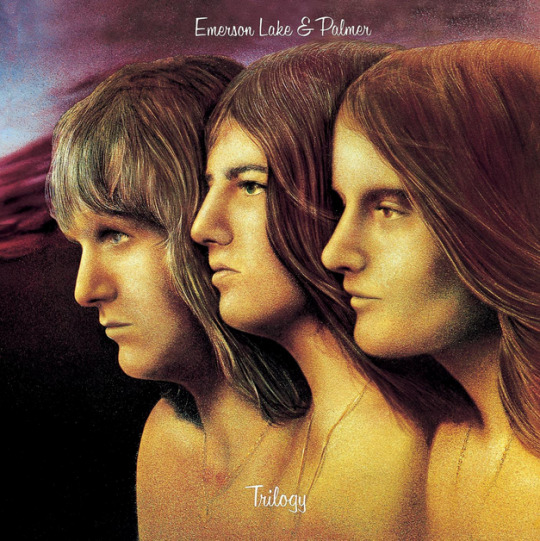

EMERSON, LAKE & PALMER - TRILOGY (1972): 6/10

(Originally posted on 23 July, 2017)

Alright, so that break was a little longer than I’d hoped, but honestly, it’s not as easy to come up with things to say about some albums as it is for other albums. Case in point: Trilogy, while not bad, is certainly not an essential entry in Emerson, Lake & Palmer’s discography and covers very little new ground. It also has one of the worst album covers I’ve seen so that doesn’t help the situation any. Sigh… How far we’ve strayed from the giant armadillo tanks of yore…

Instead of having one giant long-winded epic track, the band this time decided to have three slightly less giant ones (“The Endless Enigma”, “Trilogy” and “Abaddon’s Bolero”) in addition to some shorter songs: another Greg Lake ballad (“From The Beginning”), another joke track in the tradition of “Jeremy Bender” (“The Sheriff”; although this time the band put a lot more effort into creating a less generic and more complex melody, so that it doesn’t feel like a throwaway. It’s also got some funny lyrics and you can hear Carl Palmer say “shit” when he screws up his drum solo at the start, so check it out), and another synth-dominated cover of a classical piece (“Hoedown”, originally by Aaron Copland). The only other track that’s under five minutes is “Living Sin”, which is pretty forgettable, and Greg Lake puts up a low grumbly voice on it which is just kinda ugly. Skip it!

Unfortunately, the epics generally don’t work quite as well as on the preceding albums. All three of them are around eight minutes long but most of them don’t really seem to have enough musical ideas to support that runtime. I suppose “The Endless Enigma” works well enough as a bombastic album opener, and it helps that the musicians are all still in top form and having a blast (I especially enjoy the little piano and bass fugue in between the two parts of the suite), but the chorus is just not as memorable or energetic as that of similar songs the guys made before and after. I’m also not a fan of the title track. It starts off as another Greg Lake-dominated ballad, but not a good one: it's just sappy, with Keith offering a minimal piano background and Greg occasionally trying out a falsetto and failing. The lyrics don't help matters either ("We tried to lie / but you and I / know better than to let each other lie / The thought of lying to you makes me cry" [Thank God they hired someone else to write lyrics for them on the next album...]). The song then leads into a sort of cool jazzy jam before ending with a jolly fast-paced part that’s still a little boring. The problem is not even just that the melody sucks, but mostly it’s how monotonous the arrangement is. I think Emerson uses the same synth tone throughout 90% of the album.

If you ask me, there are only two tracks that really justify this album’s existence. One is “From The Beginning”: while it follows the same format as “Lucky Man” (an acoustic guitar ballad with a synthesizer solo), it feels far less banal and more introspective. Plus, the synth solo is a lot less extravagant and fits the song much better, whereas on “Lucky Man” it seemed to come out of nowhere and felt really out of place.

My favourite track however is “Abaddon’s Bolero”, which is indeed a bolero: a melody is repeated again and again over a simple military march rhythm, with new layers being added every time. Remember what I said about Keith’s synth sounds not being diverse enough on this album? Well, on this track he makes up for it and pulls everything he can out of the instrument, starting with a barely audible flute-like tone and eventually ending up with a vast array of different sounds and melodies that all play simultaneously, like a synthesized orchestra (complete with fake trombone glissandos!). I realize that the song’s repetitive nature could just as easily drive you up the wall, though. Ah well, I would never claim that this sort of music (or really, any sort of music) is for everyone. Give it a chance, is all I can say.

Best song: ABADDON’S BOLERO

0 notes

Photo

NATIONAL HEALTH - D.S. AL CODA (1982): 8/10

(Originally posted on 18 February, 2017)

After the release of Of Queues And Cures, National Health was joined by cellist Georgie Born and bassoonist Lindsay Cooper, who had played guest roles on the album and had previously been John Greaves’ bandmates in Henry Cow. One can only dream of what sort of material this miniature chamber orchestra would be capable of producing, but it sadly wasn’t to be: frustrated with the band’s consistent lack of success, Dave Stewart finally decided enough was enough and pulled the plug on his involvement with the project in order to join Bill Bruford’s band. The band fell apart after this: Miller, Pyle and Greaves managed to reunite with Alan Gowen for a few more tours in 1979, but there was no more desire to record a new album beyond that

This changed in 1981, when Gowen died of leukaemia at the age of 33. In order to commemorate him, Stewart, Miller, Pyle and Greaves reunited one more time to record an album featuring a number of Gowen’s compositions. The resulting product was released as the final National Health album in 1982.

D.S. Al Coda is much more a product of its time than its predecessors. The production style is more monotone and definitely shows some 80s influence, with Dave Stewart’s synthesizers dominating the sound (rather than his usually wide variety of different keyboards) while the more exotic instruments are far less prominent than on the last album (Elton Dean and Jimmy Hastings show up on saxophone and flute respectively on a few tracks, but that’s about it). Even Pip Pyle’s drums are electronically enhanced, as was the standard at the time. This move is accentuated by the first track, “Portrait Of A Shrinking Man”, which is atypical for National Health, to say the least: a slightly funky yet melancholic groove prominently featuring a fretless bass and a horn section. It’s more or less similar to what bands like Weather Report were doing at the time, which for this band’s standards isn’t too exciting but it’s still fun to listen to, and the main melody is really catchy too.