Text

Making Oncology Accessible in Nepal

By SAURABH JHA, MD

In this episode of Radiology Firing Line Podcast, I speak with Bishal Gyawali MD, PhD. Dr. Gyawali obtained his medical degree from Kathmandu. He received a scholarship to pursue a PhD in Japan. Dr. Gyawali’s work focuses on getting cheap and effective treatment to under developed parts of the world. Dr. Gyawali is an advocate for evidence-based medicine. He has published extensively in many high impact journals. He coined the term “cancer groundshot.” He was a research fellow at PORTAL. He is currently a scientist at the Queen’s University Cancer Research Institute in Kingston, Ontario.

Listen to our conversation here.

Saurabh Jha is an associate editor of THCB and host of Radiology Firing Line Podcast of the Journal of American College of Radiology, sponsored by Healthcare Administrative Partner.

Article source:The Health Care Blog

0 notes

Text

MedPAC’s Latest Bad Idea: Forcing Doctors to Join ACOs

By KIP SULLIVAN, JD

At its April 4, 2019 meeting, the staff of the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC) asked the commission to discuss a very strange proposal: Doctors who treat patients enrolled in Medicare’s traditional fee-for-service (FFS) program must join an “accountable care organization” (ACO) or give up their FFS Medicare practice. (The staff may have meant to give hospitals the same Hobbesian choice, but that is not clear from the transcript of the meeting.)

Here is how MedPAC staffer Eric Rollins laid out the proposal:

Medicare would require all fee-for-service providers to participate in ACOs. The traditional fee-for-service program would no longer be an option. Providers would have to join ACOs to receive fee-for-service payments. Medicare would assign all beneficiaries to ACOs and would continue to pay claims for ACOs using standard fee-for-service rates. Beneficiaries could still enroll in MA [Medicare Advantage] plans. (p. 12 of the transcript)

The first question that should have occurred to the commissioners was, Are ACOs making any money? If they aren’t, there’s no point in discussing a policy that assumes ACOs will flourish across the country.

But only two of the 17 commissioners bothered to raise that issue. They asserted that Medicare ACOs are saving little or no money. Those two commissioners – Paul Ginsburg and commission Vice Chairman Jon Christianson – did not mince words. Ginsburg said ACO savings were “slight” and called the proposal to push doctors into ACOs “hollow” and premature. (pp. 62-63) Christianson was even more critical. He said the proposal was “really audacious,” and that no “strong evidence” existed to support the claim that ACOs “can reduce costs for the Medicare program or improve quality.” (pp. 73-74) Ginsburg and Christianson are correct – ACOs are not cutting Medicare’s costs when Medicare’s “shared savings” payments to ACOs are taken into account, and what little evidence we have on ACO overhead indicates CMS’s small shared savings payments are nowhere near enough to cover that overhead.

But Ginsburg and Christianson might as well have been talking to a wall. The other 15 commissioners had no comment. In fact, the majority of them said ACOs are saving money for Medicare and endorsed further consideration of the staff’s suggestion that doctors should have to choose between joining an ACO or never again billing the FFS Medicare program.

The only other objection offered at the meeting came from commissioner Marjorie Ginsburg. She noted that under the staff’s proposal beneficiaries would have to enroll in an ACO (currently beneficiaries are assigned to one without their knowledge), and they would have to suffer financial penalties if they saw providers outside of their ACO. But, she warned, that will be “a really hot-button issue and we have to be extremely careful in how we present this going forward or we’re going to get hammered.” (p. 88) Yet even Ginsburg said punishing doctors who didn’t join ACOs was worth further discussion.

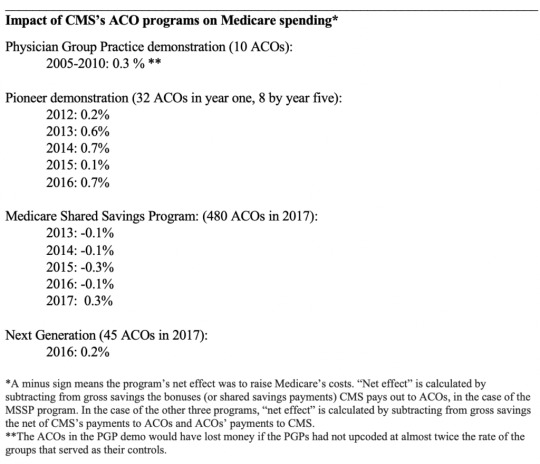

Four ACO programs, same results: No savings

As the table below indicates, the four ACO programs the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) has established since 2005 have had almost no impact on Medicare spending. [1] The four programs have raised or lowered Medicare’s net spending by only a few tenths of a percent. Please note that three of the four programs – the Physician Group Practice (PGP) demonstration (which ran from 2005 to 2010), the Pioneer ACO demonstration (2012 to 2016), and Next Generation demonstration (it began in 2016) – exposed ACOs to two-sided risk, that is, to the risk of sharing losses as well as savings. Only the Medicare Shared Savings Program (MSSP), a permanent program that began in 2012, exposed ACOs only to upside risk (the chance to make money). I point this out because ACO proponents seek to excuse the poor performance of the MSSP by claiming MSSP ACOs are not exposed to downside risk (the risk of losing money). The best known proponent of this evidence-free explanation is probably Seema Verma, Trump’s CMS administrator. MedPAC also promotes this notion. But as the table indicates, exposure to downside risk makes little difference. The three two-sided-risk programs performed only a few tenths of a percent better than the MSSP has.

Sources: For the PGP demo, see p. 64 of Evaluation of the Medicare Physician Group Practice Demonstration.

For the Pioneer, MSSP and Next Generation programs, see Tables 8-6, 8-3, and 8-7 respectively of Chapter 8 of MedPAC’s June 2018 report to Congress. The 2017 figure for the MSSP program is from slide 9 of a presentation to MedPAC at their January 2019 meeting.

ACO proponents have not been happy with these results. But rather than concede the ACO isn’t working, they have argued there is something wrong with the way CMS measures ACO savings and losses. They say CMS’s use of historical rather than concurrent control groups renders CMS’s estimates of savings and losses inaccurate. If CMS would use concurrent controls, they say, ACOs would look better.

I won’t get into the gory details of this claim. [2] All you really need to know is that research using concurrent controls produces the same underwhelming results – ACOs still save only a few tenths of a percent. For example, the study of the PGP demo that produced the measly three-tenths of a percent savings (see table above) used concurrent controls. Similarly, a study of the MSSP by J. Michael McWilliams using concurrent controls reported a seven-tenths-of-one-percent savings for 2013-2014 (my calculation based on data reported in Table 2, p. 1712), while the National Association of ACOs reported a three-tenths-of-a-percent savings for the MSSP for 2013-2015 (see slide 9 in this presentation by MedPAC staff at the commission’s January 2019 meeting).

No margin, no mission

So if Medicare ACOs are breaking even for Medicare, or are at best cutting Medicare’s costs by half a percent net, that means the average ACO is receiving about half of that tiny savings in the form of shared savings payments, i.e., somewhere between zero and a quarter of a percent. And that in turn means the average ACO is losing money. Our commonsense tells us that has to be true because we know no human enterprise can operate without at least some overhead costs, and the overhead costs incurred by ACOs have to be a lot higher than one-fourth of a percent.

So, you ask, how high are Medicare ACO overhead costs? Surely after 14 years and four ACO programs, CMS, the ACO industry, and health services researchers have published research on this issue. Wrong. The only information we have are occasional statements by MedPAC, based on nothing more than a few interviews with ACO managers, that ACO administrative costs total approximately 2 percent. MedPAC informs us, moreover, that this number does not include extra services given to patients by ACOs in their (largely futile) efforts to cut net Medicare spending. Those two numbers together – administrative costs plus the cost of additional services delivered directly to patients such as educational and transportation services – may well exceed ten percent of total Medicare Part A and B spending attributable to some or most ACOs. [3]

Even if ACO overhead is just 2 percent, what possible rationale is there for continuing the ACO experiment, much less for forcing doctors to choose between joining an ACO and giving up their FFS Medicare practice? There is none.

Learning from the crash of lead balloons

How do we explain MedPAC’s obtuse behavior?

Unfortunately, this problem is not peculiar to MedPAC, it’s just more visible within MedPAC because, unlike the numerous other institutions that endorse evidence-free health policy, the commission’s deliberations are public. MedPAC’s dysfunctional thinking reflects habits of thought generated within the larger culture created by the managed care movement decades ago (for a longer discussion of this culture, see pp. 154-170 of my article with Ted Marmor). These habits of thought – a preference for abstraction, frequent use of labels designed to manipulate rather than inform (i.e. “accountable care”), and a cavalier attitude toward evidence (i.e., no interest in ACO overhead costs and misrepresentation of research on ACOs) – are rarely challenged by MedPAC members, in part because experts who don’t exhibit these habits of thought are rarely appointed to the commission. And on the infrequent occasion when those habits are challenged by one of the commissioners, no discussion ensues.

The commission’s failure to discuss Jon Christianson’s unvarnished criticism of ACOs at its April 4 meeting is a good example. In addition to asserting that ACOs are not saving money, he warned his fellow commissioners that ACOs are even less likely to work today than five years ago because of the rapid consolidation of the system. He cited the recent “Aetna-CVS kind of vertical merger, [and] all of the horizontal mergers that we’ve seen in the hospital industry.”(p. 76) The response? Crickets.

Because MedPAC has been such a prolific endorser of evidence-free health policy fads (pay-for-performance [P4P], incentives to buy electronic medical records, “medical homes,” ACOs, punishment for “excess readmissions,” etc.), it is conceivable the commission’s devotion to orthodoxy will eventually be undermined by reality – by a string of undeniable failures of programs MedPAC recommended. MedPAC’s endorsement of P4P in the early 2000s and its subsequent retraction of P4P for individual doctors (as opposed to groups) illustrates this possibility. In 2015, Congress accepted the advice of MedPAC and other managed care proponents and enacted what may be the planet’s largest P4P program – the doomed Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) (it was part of the MACRA law). At that point, MedPAC resembled the dog that caught the car. They had what they had been recommending for over a decade, and now it didn’t look like anything they could use. After a long delay, MedPAC voted (on January 11, 2018) to urge Congress to repeal MIPS.

Was the MIPS vote an aberration? Let us hope not.

Kip Sullivan is a member of the Health Care for All Minnesota advisory board and of the Minnesota chapter of Physicians for a National Health Program.

Footnotes

[1] The table does not list two smaller ACO programs run by CMS – a demonstration for dialysis centers, and a one-ACO program for Vermont known as the Vermont All-Payer ACO Model demonstration.

[2] In this footnote I’ll introduce the reader to the main issues raised by those ACO proponents who argue that CMS’s use of historical controls is not as accurate as research using concurrent controls. I’ll begin by noting, as I did in the text, that this argument can’t explain the paltry three-tenths-of-a-percent savings for the PGP demonstration. CMS used a concurrent control group in that demo.

For the three post-2012 programs (Pioneer, MSSP, and Next Generation), CMS has used historical control groups against which to measure ACO success or failure. CMS constructs these control groups first by assigning Medicare beneficiaries to ACOs based on which primary care doctors Medicare beneficiaries saw during a three-year look-period, that is, the three years preceding the performance year. CMS then calculates the expenditures on these assignees during the look-back period and, after making several adjustments including building in an increase to reflect inflation during the performance year, sets a target for the performance year. Thus, the assignees during the three-year look-back period serve as the controls for the performance year.

The critics of CMS’s method allege that CMS’s historical controls don’t adjust ACO performance to take account of confounding factors as well as concurrent control groups would. Why this should be so is never explained clearly. Both forms of controls have advantages and disadvantages. The estimates derived with the use of concurrent controls may be inferior because the construction of concurrent controls introduces serious confounding factors which are not introduced by historical controls and which are difficult to measure accurately. The most serious of these is the necessity of changing the pool of beneficiaries who were in the ACOs during the time period studied. McWilliams, for example, altered the real-world pool of ACO assignees (the experimental group) by making up his own assignment algorithm – an algorithm that differs substantially from the one CMS uses.

A second serious defect in concurrent-control studies is their use of CMS’s real-world shared savings payments to ACOs to calculate the net savings or losses. What is the logic of calculating gross savings or losses using a pool of assignees that was different from the real-world pool, and then using only the real-world data on CMS payments to ACOs to calculate the net?

[3] The 2 percent figure for ACO overhead (the percent of Part A and Part B spending attributed to an ACO that is eaten up by the cost of administering the ACO) has appeared in at least two MedPAC documents – the transcript of the September 11, 2014 MedPAC meeting, and MedPAC’s June 2018 report to Congress.

According to the transcript of the September 2014 meeting, then-commissioner David Nerenz asked MedPAC staffer Jeff Stensland if “we know anything about” ACO “overhead.” Stensland replied, “[P]eople we talk to and the data we have seen, it looks like maybe 1 to 2 percent of your spend, that that’s what they’re spending on their ACO to operate it….” (p 133). Stensland concluded, “[I]f you averaged everybody [that is, all ACOs] … the share of savings … that they get is going to be less than their administrative costs….” (p. 144)

MedPAC’s June 2018 report to Congress stated: “Our discussions with ACOs suggest their administrative costs, in contrast to those of MA plans, are close to $200 per beneficiary per year,” or about 2 percent of the $10,000 it costs Medicare to cover Part A and Part B expenses.

But judging from the way the June 2018 report described “administrative costs,” that 2 percent estimate is way below total ACO overhead – administrative costs plus the costs ACOs incur to finance the interventions they hope will reduce Medicare spending. Here’s how the June 2018 report described administrative costs: “ACOs do not have the costs of advertising, enrolling, negotiating contracts, and paying claims. Their administrative costs include the expense of setting up and managing the ACO, which should include data analysis and reporting quality measures.” (p. 236) That definition obviously excludes other ACO-related costs, notably the cost of services delivered directly to patients that are supposed to reduce billable Medicare services. These additional services require hiring new staff, such as nurses and social workers and cab drivers, or changing the job descriptions of existing staff.

What might those additional services cost? Again, we have almost no information. We get some idea of how extensive, and expensive, these services can be by examining a list of such services provided by Partners Healthcare Systems’ ACO (the second-largest of the 32 original Pioneer ACOs) to 4,000 of its sicker assignees. I extracted the list below from RTI International’s 2010 evaluation of Partners’ “care management program” (CMP). According to a 2017 report by John Hsu et al., that program constituted most of the interventions Partners’ ACO financed in its futile attempt to save money for Medicare. Here is the list:

“Eleven nurse case managers [each of whom worked with about 200 patients] who received guidance from the program leadership and support from the project manager, an administrative assistant, and a community resources specialist” (p. 7);

“a social worker to assess the mental health needs of CMP participants” (p. 6);

“a mental health team director, clinical social worker, two psychiatric social workers, and a forensic clinical specialist (M.D./J.D.), who follows highly complex patients with issues such as legal issues, guardianship and substance abuse” (p. 10);

“a pharmacist to review the appropriateness of medication regimens” (p. 6);

“home delivery of medications five days per week” (p. 7);

“a nurse who specialized in end-of-life-care issues” (p. 7);

“a patient financial counselor who provided support for all insurance related issues” (p. 7);

“The clinical team leader provided oversight and supervision of case managers” (p. 8);

“The medical director provided oversight and day to day management of MGH’s [Massachusetts General Hospital’s] CMP….” (p. 8);

“MGH developed a series of clinical dashboards using data from the MGH electronic medical record …, claims data, and its enrollment tracking database” (p. 8);

“MGH provided [200] physicians with a $150 financial incentive per patient per year to help cover the cost of physician time for [CMP-related] activities” (p. 8);

“a designated case manager position to work specifically on post discharge assessments to enhance transitional care monitoring” (p. 9);”

“a data analytics team to develop and strengthen program’s reporting capabilities” (p. 10); and

numerous housing, transportation and other “support services” and “community services” (p. 6) that RTI described only vaguely.

Article source:The Health Care Blog

0 notes

Text

Now More Than Ever, the Case for Medicaid Expansion

Sam Aptekar

Phuoc Le

By PHUOC LE, MD and SAM APTEKAR

A friend of mine told me the other day, “We’ve seen our insured patient population go from 15% to 70% in the few years since Obamacare.” As a primary care physician in the Midwest, he’s worked for years in an inner-city clinic that serves a poor community, many of whom also suffer from mental illness. Before the Affordable Care Act (ACA), the clinic constantly struggled to stay afloat financially. Too often patients would be sent to an emergency room because the clinic couldn’t afford to provide some of the simplest medical tests, like an x-ray. Now, with most of his patients insured through the Medicaid expansion program, the clinic has beefed up its staffing and ancillary services, allowing them to provide better preventive care, and in turn, reduce costly ER visits.

From the time Medicaid was established in 1965 as the country’s first federally-funded health insurance plan for low-income individuals, state governments have only been required to cover the poorest of their citizens. Before the ACA, some 47 million Americans were uninsured because their incomes exceeded state-determined benchmarks for Medicaid eligibility and they earned far too little to buy insurance through the private marketplace.

The ACA reduced the number of uninsured Americans by mandating that states increase their income requirement for Medicaid to 138% of the federal poverty line (about $1,330 per month for a single individual), and promising that the federal government would cover the cost to do so. However, in a 2012 decision, the Supreme Court left it to the states to decide if they wanted to increase their Medicaid eligibility. If they agreed to adopt Medicaid expansion, the federal government offered to cover 100% of the increased cost in 2014 and 90% by 2021.

Medicaid expansion and non-expansion states. Source: Kaiser Family Foundation

Given the demonstrable health benefits of Medicaid expansion in Kentucky, it may come as a surprise to hear that Governor Matt Bevin has implemented work and volunteer requirements for Medicaid beneficiaries in an attempt to significantly reduce the number of eligible Medicaid applicants. Echoing an argument made by opponents in the fourteen states that remain unexpanded and the several others who are introducing similar measures to rollback signups, Governor Bevin claims that even though federal funds will foot the overwhelming majority of the cost, increased Medicaid enrollment will cost state taxpayers billions of dollars.

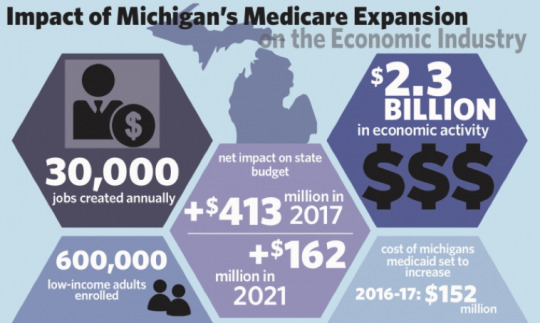

However, data from states that have already expanded suggests this claim is statistically unsubstantiated. In Montana, for example, Medicaid expansion cost the state $24 million in 2017, but saved them close to $25 million by decreasing the uninsured rate, ultimately “leaving Montana with a surplus of $700,000” in the 2017 fiscal year. Arkansas and Kentucky, two original expansion states, accumulated enough savings from the first two years of expansion to cover the costs until 2021 on their own. We see a similar story in Michigan, where a state-wide studyby a team of researchers at the Gerald School of Public Policy “confirms that federal funding for Medicaid expansion offers states a fiscal benefit through reduced state spending on Medicaid-covering services and a macroeconomic benefit through increased economic activity…”

Impact of Medicaid Expansion in Michigan. Source: Michigan Daily

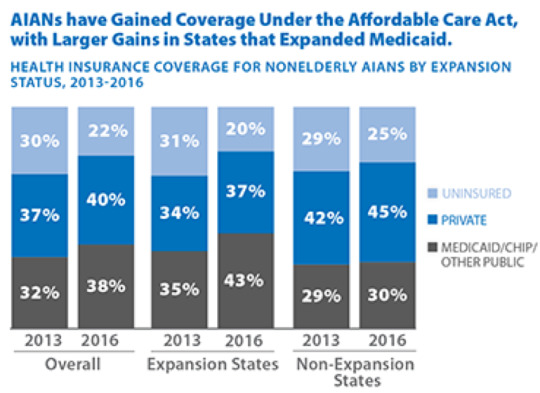

For American Indians and Alaska Natives (AIAN), the implications of Medicaid expansion are particularly high. In states that have adopted expansion, hospitals and clinics under Indian Health Services, the federal program offering healthcare to enrolled tribal members, have significantly increased the number of patients they treat with health insurance, allowing them to bill for services that had been previously uncompensated. The augmented revenue from compensated care has allowed these hospitals and clinics to increase their personnel and offer services that have been long denied. In Montana, for example, Native Americans represent only 8% of the population, but 16% of residents covered under Medicaid expansion, laying a particularly heavy burden on AIAN communities if expansion were rolled back or cut altogether.

Native American Insurance Gain after Medicaid Expansion. Source: Kaiser Family Foundation.

By any meaningful metric, the ACA has transformed the landscape of care for the poor and underserved. The evidence is clear: Medicaid expansion is not only morally responsible, but also fiscally verified. As a study by the Brookings Institute concluded, “The strong balance of objective evidence indicates that actual costs to states so far from expanding Medicaid are negligible or minor, and that states across the political spectrum do not regret their decision to expand Medicaid.” If the best healthcare at the lowest cost is truly the goal of lawmakers, then accepting the ACA’s offer to have the federal government finance no less than 90% of the increased cost of expansion is a proven step forward. However, fourteen states continue to refuse the deal and other states that have expanded, such as Arkansas, Montana, and Kentucky, have introduced measures that attempt to roll back Medicaid eligibility.

Physicians and other healthcare providers living in the fourteen states that have yet to expand or in those rolling back eligibility have the political capital to influence voters and state legislatures. It is our responsibility as clinicians to vocalize support for measures that have proven effective for the communities we serve. Now more than ever, facing an administration actively cutting Medicaid enrollment, we must resist efforts to deny our patients access to their healthcare, and raise our voices for further expansion of health insurance coverage for all.

Internist, Pediatrician, and Associate Professor at UCSF, Dr. Phuoc Le is also the co-founder of two health equity organizations, the HEAL Initiative and Arc Health.

Sam Aptekar is a recent graduate of UC Berkeley and a current content marketing and blogging affiliate for Arc Health Justice.

This post originally appeared on Arc Health here.

Article source:The Health Care Blog

0 notes

Text

Patient-Directed Access for Competition to Bend the Cost Curve

By ADRIAN GROPPER, MD

Many of you have received the email: Microsoft HealthVault is shutting down. By some accounts, Microsoft has spent over $1 Billion on a valiant attempt to create a patient-centered health information system. They were not greedy. They adopted standards that I worked on for about a decade. They generously funded non-profit Patient Privacy Rights to create an innovative privacy policy in a green field situation. They invited trusted patient surrogates like the American Heart Association to participate in the launch. They stuck with it for almost a dozen years. They failed. The broken market and promise of HITECH is to blame and now a new administration has the opportunity and the tools to avoid the rent-seekers’ trap.

The 2016 21st Century CURES Act is the law. It is built around two phrases: “information blocking” and “without special effort” that give the administration tremendous power to regulate anti-competitive behavior in the health information sector. The resulting draft regulation, February’s Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (NPRM) is a breakthrough attempt to bend the healthcare cost curve through patient empowerment and competition. It could be the last best chance to avoid a $6 Trillion, 20% of GDP future without introducing strict price controls.

This post highlights patient-directed access as the essential pro-competition aspect of the NPRM which allows the patient’s data to follow the patient to any service, any physician, any caregiver, anywhere in the country or in the world.

The NPRM is powerful regulation in the hands of an administration caught between anti-regulatory principles and an entrenched cabal of middlemen eager to keep their toll booth on the information highway. Readers interested in or frustrated by the evolution of patient-directed interoperability can review my posts on this over the HITECH years: 2012; 2013; 2013; 2014; 2015.

The struggle throughout has been a reluctance to allow digital patient-directed information exchange to bypass middlemen in the same way that fax or postal service information exchange does not introduce a rent-seeking intermediary capable of censorship over the connection.

Middlemen

Who are the middlemen? Simply put, they are everyone except the patient or the physician. Middlemen includes hospitals, health IT vendors, health information exchanges, certifiers like DirectTrust and CARIN Alliance, and a vast number of hidden data brokers like Surescripts, Optum, Lexis-Nexis, Equifax, and insurance rating services. The business model of the middlemen depends on keeping patients and physicians from bypassing their toll booth. In so doing, they are making it hard for new ventures to compete without paying the overhead imposed by the hospital or the fees imposed by the EHR vendors.

But what about data cleansing, search and discovery, outsourced security, and other value-added services these middlemen provide? A value-added service provider shouldn’t need to put barriers to bypass to stay in business. The doctor or patient should be able to choose which value-added services they want and pay for them in a competitive market. Information blocking and the requirement for special effort on the part of the patient or the physician would be illogical for any real value-added service provider.

In summary, patient-directed access is simply the ability for a patient to direct and control the access of information from one hospital system to another “without special effort”. Most of us know what that looks like because most of us already direct transfer of funds from one bank to another. We know how much effort is involved. We know that we need to sign-in to the sending bank portal in order to provide the destination address and to restrict how much money moves and whether it moves once or every month until further notice. We know that we can send this money not just to businesses but to anyone, including friends and family without censorship or restriction. In most cases today, these transfers don’t cost anything at all. Let’s call this kind of money interoperability “without special effort”.

Could interoperating money be even less effort than that? Yes. For instance, it’s obnoxious that each bank and each payee forces us to use a different user interface. Why can’t I just tell all of my banks and payees: use that managing agent or trustee that I choose? Why can’t we get rid of all of the different emails and passwords for each of the 50+ portals in our lives and replace them with a secure digital wallet on our phone with fingerprint or face recognition protection? This would further reduce the special effort but it does require more advanced standards. But, at least in payment, we can see it coming. Apple, for instance gives me a biometric wallet for my credit cards and person-to person payments. ApplePay also protects my privacy by not sharing my credit card info with the merchants. Beyond today’s walled garden solutions, self-sovereign identity standards groups are adding the next layer of privacy and security to password-less sign-in and control over credentials.

Rent Seekers

But healthcare isn’t banking because HITECH fertilized layers upon layers of middlemen that we, as patients and doctors, do not control and sometimes, as with Surescripts, don’t even know exist. You might say that Visa or American Express are middlemen but they are middlemen that compete fiercely for our consumer business. As patients we have zero market power over the EHR vendors, the health information exchanges, and even the hospitals that employ our doctors. Our doctors are in the same boat. The EHR they use is forced on them by the hospital and many doctors are unhappy about that but subject to gag orders unprecedented in medicine until recently.

This is what “information blocking” means for patients and doctors. This is what the draft NPRM is trying to fix by mandating “without special effort”. This is what the hospitals, EHR vendors, and health information exchanges are going to try to squash before the NPRM becomes final. After the NPRM becomes a final regulation, presumably later in 2019, the hospitals and middlemen will have two years to fix information blocking. That brings us to 2022. Past experience with HITECH and Washington politics assures us of many years of further foot dragging and delay. We’ve seen this before with HIPAA, misinterpreted by hospitals in ways that frustrate patients, families, and physicians for over a decade.

Large hospital systems have too much political power at the state and local level to be driven by mere technology regulations. They routinely ignore the regulations that are bad for business like the patient-access features of HIPAA and the Accounting for Disclosures rules. Patients have no private right of action in HIPAA and the federal government has not enforced provisions like health records access abuses or refusal to account for disclosures. Patients and physicians are not organized to counter regulatory capture by the hospitals and health IT vendors.

The one thing hospitals do care about is Medicare payments. Some of the information blocking provisions of the draft NPRM are linked to Medicare participation. Let’s hope these are kept and enforced after the final regulations.

Competition to Bend the Cost Curve

Government has two paths to bending the cost curve: setting prices or meaningful competition. The ACA and HITECH have done neither. In theory, the government could do some of both but let’s ignore the role of price controls because it can always be added on if competition proves inadequate. Anyway, we’re in an administration that wants to go the pro-competition path and they need visible progress for patients and doctors before the next election. Just blaming pharma for high costs is probably not enough.

Meaningful competition requires multiple easy choices for both the patients and the prescribers as well as transparency of quality and cost. This will require a reversal of the HITECH strategy that allows large hospitals and their large EHRs to restrict the choices offered and to obscure the quality and cost behind the choices that are offered. We need health records systems that make the choice of imaging center, lab, hospital, medical group practice, direct primary care practice, urgent care center, specialist, and even telemedicine equally easy. “Without special effort”.

The NPRM has the makings of a pro-competitive shift away from large hospitals and other rent-seeking intermediaries but the elements are buried in over a thousand pages of ONC and CMS jargon. This confuses implementers, physicians and advocates and should be fixed before the regulations are finalized. The fix requires a clear statement that middlemen are optional and the interoperability path that bypasses the middlemen as “data follows the patient” is the default and “without special effort”. What follows are the essential clarifications I recommend for the final information blocking regulations – the Regulation, below.

Covered Entity – A hospital or technology provider subject to the Regulation and/or to Medicare conditions of participation.

Patient-directed vs. HIPAA TPO – Information is shared by a covered entity either as directed by the patient vs. without patient consent under the HIPAA Treatment, Payment, or Operations.

FHIR – The standard for information to follow the patient is FHIR. The FHIR standard will evolve under industry direction, primarily to meet the needs of large hospitals and large EHR vendors. The FHIR standard serves both patient-directed and HIPAA TPO sharing.

FHIR API – FHIR is necessary but not synonymous with a standard Application Programming Interface (API). The FHIR API can be used for both patient-directed and TPO APIs. Under the Regulation, all patient information available for sharing under TPO will also be available for sharing under patient direction. Information sharing that does not use the FHIR API, such as bulk transfers or private interfaces with business partners will be regulated according to the information blocking provisions of the Regulations.

Server FHIR API – The FHIR API operated by a Covered Entity.

Client FHIR API – The FHIR API operated by a patient-designee. The patient designee can be anyone (doctor, family, service provider, research institution) anywhere in the world.

Patient-designee – A patient can direct a Covered Entity to connect to any Client FHIR API by specifying either the responsible user of a Client FHIR API or the responsible institution operating a Client FHIR API. Under no circumstances does the Regulation require the patient to use an intermediary such as a personal health record or data bank in order to designate a Client FHIR API connection. Patient-controlled intermediaries such as personal health records or data banks are just another Client FHIR API that happen to be owned, operated, or controlled by the patient themselves.

Dynamic Client Registration – The Server FHIR API will register the Client FHIR API without special effort as long as the patient clearly designates the operator of the Client. Examples of a clear designation would include: (a) a National Provider Identifier (NPI) as published in the NPPES https://npiregistry.cms.hhs.gov; (b) an email address; (c) an https://… FHIR API endpoint; (d) any other standardized identifier that is provided by the patient as part of a declaration digitally signed by the patient.

Digital Signature – The Client FHIR API must present a valid signed authorization token to the Server FHIR API. The authorization token may be digitally signed by the patient. The patient can sign such a token using: (a) a patient portal operated by the Server FHIR API; (b) a standard Authorization Server designated by the patient using the patient portal of the sever operator (e.g. the UMA standard referenced in the Interoperability Standards Advisory); (c) a software statement from the Client FHIR API that is digitally signed by the Patient-designee.

Refresh Tokens – Once the patient provides a digital signature that enables a FHIR API connection, that signed authorization should suffice for multiple future connections by that same Client FHIR API, typically for a year, or until revoked by the patient. The duration of the authorization can be set by the patient and revoked by the patient using the patient portal of the Server FHIR API.

Patient-designated Authorization Servers – The draft NPRM correctly recognizes the problem of patients having to visit multiple patient portals in order to review which Clients are authorized to receive what data and to revoke access authorization. A patient may not even know how many patient portals they have enabled and how to reach them to check for sharing authorizations. By allowing the patient to designate the FHIR Authorization Server, a Server FHIR API operator would enable the patient to choose one service provider that would then manage authorizations in one place. This would also benefit the operator of the Server FHIR API by reducing their cost and risk of operating an authorization server. UMA, as referenced in the Interoperability Standards Advisory is one candidate standard for enhancing FHIR APIs to enable a patient-designated authorization server.

Big Win for Patients and Physicians

As I read it, the 11 definitions above are consistent with the draft NPRM. Entrepreneurs, private investors, educators, and licensing boards stand ready to offer patients and physicians innovative services that compete with each other and with the incumbents that were so heavily subsidized by HITECH. To encourage this private-sector investment and provide a visible win to their constituents, Federal health architecture regulators and managers, including ONC, CMS, VA, and DoD would do well to reorganize the Regulations in a way that makes the opportunity to compete on the basis of patient-directed exchange as clear as possible. As an alternative to reorganizing the Regulations, guidance could be provided that makes clear the 11 definitions above. Furthermore, although it could take years for the private-sector covered entities to fully deploy patient-directed sharing, deployments directly controlled by the Federal government such as access to the Medicare database and VA-DoD information sharing could begin to implement patient-directed information sharing “without special effort” immediately. Give patients and doctors the power of modern technology.

Adrian Gropper, MD, is the CTO of Patient Privacy Rights, a national organization representing 10.3 million patients and among the foremost open data advocates in the country.

Article source:The Health Care Blog

0 notes

Text

Health in 2 Point 00, Episode 77 | ATA19, Cityblock, & Microsoft HealthVault

Today on Health in 2 Point 00, Jess and I are in New Orleans at the ATA Annual Conference. In this episode, Jess asks me about my takeaways from the conference, Cityblock’s $65 million raise, and Microsoft HealthVault shutting down. In terms of virtual care, it seems that there’s been low adoption of telehealth visits—but things are on the cusp, with lots of companies doing interesting things and with CMS expanding Medicare Advantage coverage of telehealth services. —Matthew Holt

youtube

Article source:The Health Care Blog

0 notes

Text

Announcing the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Social Determinants of Health and Home & Community Based Care Innovation Challenges

By DIANA CHEN

The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF) has partnered with Catalyst @ Health 2.0 to launch two innovation challenges on Social Determinants of Health (SDoH) and Home & Community Based Care. As a national leader in building a culture of health, RWJF is inspiring and identifying novel digital solutions to tackle health through an unconventional lens.

Health starts with where we live. As noted in Healthy People 2020 social determinants of health are, “conditions in the environments in which people are born, live, learn, work, play, worship, and age… [that] affect a wide range of health functioning, and quality-of-life outcomes and risks.” For example, children who live in an unsafe area cannot play outside making it more difficult for them to have adequate exercise. Differences in SDoH heavily influences communities’ well-being and results in very different opportunities for people to be healthy.

Despite our knowledge on SDoH, the current healthcare system utilizes care models that often fail to take into account the social and economic landscape of communities– neglecting factors such as housing, education, food security, income, community resources, transportation and discrimination. Little progress has been made on incorporating SDoH into established health care frameworks. Healthcare providers and patients alike either have limited understanding of SDoH or have limited opportunities to utilize SDoH knowledge. RWJF established the “Social Determinants of Health Innovation Challenge” to find novel digital solutions that can help providers and/or patients connect to health services related to SDoH.

Home and community-based care is also important to enable Americans to live the healthiest lives possible. In-patient and long-term institutional care can be uncomfortable, costly, and inefficient. Digital health solutions in the home and community offer opportunities for care that better suit the patient and their loved ones. For example, innovations such as remote patient monitoring (RPM) have created new care models that allow the providers, caregivers, and patients to manage care where a person is most comfortable. RPM serves as a reminder that technologies in the home and community offer alternatives methods to engage the patient, increase access to care, and receive ongoing care. Therefore, RWJF is launching the “Home & Community-Based Care Challenge,” to encourage developers to create solutions that support the advancement of at-home or community-based health care.

The ultimate goal of both challenges is to foster innovations that help people live healthier lives and promote healthier, more equitable communities.

The challenges have two phases. In Phase I, innovators submit tech-enabled solutions addressing the challenge topic. Judges will evaluate the entries and the top five teams who will move onto Phase II. The five semi-finalists will be awarded $5,000 each to further develop their application or tool. Three finalists will be chosen at the end of Phase II to compete at a pitch event! They will demo their technology in front of a captivated audience of investors, provider organizations, and members of the media at a prominent health conference. Judges will select the first, second, and third place winners live. The grand prize winner will be awarded $40,000 for first place, $25,000 for second place, and $10,000 for third place.

With $100,000 in total prizes for each challenge and a number of promotional activities, we strongly encourage innovators to pre-register for the challenges and be notified when the applications open.

Check out the challenge websites below to learn more and make sure to pre-register for the RWJF Social Determinants of Health Innovation Challenge and/or the RWJF Home & Community Based Care Challenge to be notified when applications open on April 29th and submit your digital solution by June 7th.

To learn more about the Social Determinants of Health Innovation Challenge, click here. To pre-register for the challenge and receive the latest updates, click here.

To learn more about the Home & Community-Based Care Challenge, click here. To pre-register for the challenge and receive the latest updates, click here.

Diana Chen is a Program Associate at Catalyst @ Health 2.0. She supports international innovation programs to facilitate partnerships between healthcare organizations and innovators.

Article source:The Health Care Blog

0 notes

Text

ONC & CMS Proposed Rules – Part 4: Information Blocking

By DAVE LEVIN MD

The Office of the National Coordinator (ONC) and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid (CMS) have proposed final rules on interoperability, data blocking and other activities as part of implementing the 21st Century Cures Act. In this series, we will explore ideas behind the rules, why they are necessary and the expected impact. Given that these are complex and controversial topics open to interpretation, we invite readers to respond with their own ideas, corrections and opinions.

____________

When it comes to sharing health data, the intent of the 21st Century Cures Act is clear: patients and clinicians should have access to data without special effort or excessive cost. To make this a reality, the act addresses three major areas: technical architecture, data sets and behaviors. Part two of our series looked at how APIs address technical issues while part three covered the new data requirements. In this article, we delve into information blocking. A companion podcast interview with ONC expert Michael Lipinski provides an even deeper dive into this complex topic.

Information Blocking Comes in Many Forms

The Public Health Services Act (PHSA) broadly defines information blocking as a practice that is “likely to interfere with, prevent, or materially discourage access, exchange, or use of electronic health information.” The overarching assumption is information will be shared though the Act does authorize the Secretary to identify reasonable and necessary exceptions.

The proposed rules focus on “technical requirements as well as the actions and practices of health IT developers in implementing the certified API.” Information blocking can come in a variety of forms. It can be direct and obvious (“No you can’t have this data ever!”) or indirect and subtle (“Sure, you can have the data, but it will cost you $$$ and we won’t be able to get to your request for at least 12 months.”). The proposed rules are designed to address both. This passage illustrates some of the concerns:

“Health IT developers are in a unique position to block the export and portability of data for use in competing systems or applications, or to charge rents for access to the basic technical information needed to facilitate the conversion or migration of data for these purposes.”

It’s worth looking at examples of the proposed remedies. Here is an example that addresses anti-competitive behavior:

“Developers of health IT certified to this criterion would be required to provide the assurances proposed in § 170.402, which include providing reasonable cooperation and assistance to other persons (including customers, users and third-party developers) to enable the use of interoperable products and services.”

Another example is the Electronic Health Information (EHI) Export requirements intended to:

“…provide patients and health IT users, including providers, a means to efficiently export the entire electronic health record for a single patient or all patients in a computable, electronic format.”

These remedies provide an “exit ramp” designed to make it much easier for patients or an entire health system to change from one health IT application (typically an EHR) to another. This reduction in “switching costs” should reduce barriers to innovation and competition.

Meta-Information Blocking

While we tend to think of information blocking as solely affecting the exchange of data, open discussion and sharing of information about performance is a cornerstone of performance improvement and safety. Contractual “gag” clauses, IP concerns and other legal issues have led to meta-information blocking by limiting information exchange about system performance. As the proposed rules note, “These practices result in a lack of transparency around health IT that can contribute to and exacerbate patient safety risks, system security vulnerabilities, and product performance issues.”

These concerns are addressed directly by the Cures Act requirements, stating that:

“…a health IT developer, as a Condition and Maintenance of Certification under the Program, does not prohibit or restrict communication regarding the following subjects:

The usability of the health information technology;

The interoperability of the health information technology;

The security of the health information technology;

Relevant information regarding users’ experiences when using the health information technology;

The business practices of developers of health information technology related to exchanging electronic health information; and

The manner in which a user of the health information technology has used such technology”

Exceptions: When is Information Blocking not Information Blocking?

The expectation is that information will readily and easily flow but the rules also identify seven common sense exceptions – situations when this is not feasible or would be counter-productive. Three overarching policy considerations guided the development of these exceptions: they should advance the overall aims of the Act, reduce uncertainty about whether specific activities would constitute information blocking, and be tailored to limit their impact to reasonable and necessary activities.

These first three exceptions “address activities that are reasonable and necessary to promote public confidence in the use of health IT and the exchange of EHI. These exceptions are intended to protect patient safety; promote the privacy of EHI; and promote the security of EHI.”

The next three, “address activities that are reasonable and necessary to promote competition and consumer welfare. These exceptions would allow for the recovery of costs reasonably incurred; excuse an actor from responding to requests that are infeasible; and permit the licensing of interoperability elements on reasonable and non-discriminatory terms. “

The last exception, “addresses activities that are reasonable and necessary to promote the performance of health IT. This proposed exception recognizes that actors may make health IT temporarily unavailable for maintenance or improvements that benefit the overall performance and usability of health IT.”

Enforcement

Having rules and clarity is of limited value without enforcement. There is ample evidence that achieving robust interoperability in health care won’t be completely voluntary. Getting organizations to pay attention to and follow the rules requires meaningful enforcement. ONC’s certification authority combined with CMS’s conditions of participation provides a powerful set of carrots and sticks. When it comes to information blocking by certified health IT developers, ONC may ban a health IT developer from the program or terminate the certification. The law also authorizes the Inspector General of the Department of Health and Human Services (DHS) to investigate any claim and impose fines of up to $1,000,000 per occurrence. CMS proposes to require providers to attest to compliance and to publicly report organizations that are not in full compliance. CMS is considering additional enforcement mechanisms as well.

Summary

Information blocking–practices that interfere with the access, exchange, or use of electronic health information–comes in many forms that can be obvious or subtle. It can occur as a result of incompatible technology, limited data sets or stakeholder behaviors. ONC and CMS have crafted an interlocking set of requirements, definitions and enforcement mechanisms to address the root causes of information blocking. The expectation is that, with a few specific exceptions, information will flow in ways that enhance patient care and promote competition and innovation. The hope is that this will result in better care at lower cost, delivered in ways that are more pleasing to patients and providers alike.

Dave Levin, MD is co-founder and Chief Medical Officer for Sansoro Health where he focuses on bringing true interoperability to health care. Dave is a nationally recognized speaker, author and the former CMIO for the Cleveland Clinic.

Article source:The Health Care Blog

0 notes

Text

Why Is the USA Only the 35th Healthiest Country in the World?

By ETIENNE DEFFARGES

According the 2019 Bloomberg Healthiest Country Index, the U.S. ranks 35th out of 169 countries. Even though we are the 11th wealthiest country in the world, we are behind pretty much all developed economies in terms of health. In the Americas, not just Canada (16th) but also Cuba (30th), Chile and Costa Rica (tied for 33rd) rank ahead of us in this Bloomberg study.

To answer this layered question, we need to look at the top ranked countries in the Bloomberg Index: From first to 12th, they are Spain; Italy; Iceland; Japan; Switzerland; Sweden; Australia; Singapore; Norway; Israel; Luxembourg; and France. What are they doing right that the U.S. isn’t? In a nutshell, they embrace half a dozen critical economic and societal traits that are absent in the U.S.:

· Universal health care

· Better diet: fresh ingredients and less packaged and processed food

· Strict regulations limiting opioid prescriptions

· Lower levels of economic inequality

· Severe and effective gun control laws

· Increased attention when driving

When it comes to access to health care, the 34 countries that are ahead of the U.S. in the Bloomberg health rankings all offer universal health care to their people. This means that preventive, primary and acute care is available to 100% of the population. In contrast, 25 – 30 million Americans do not have health care insurance, and an equal number are under insured. For 15 – 18% of our population, financial concerns about how to pay for a visit to the doctor, how to meet high insurance deductibles, or cash payments after insurance take precedence over taking care of their health. Lack of preventive care leads to visits to the emergency rooms for ailments that could have been prevented through regular primary care follow-up, at a very high cost to our health system. Note: We spent $10,700 per capita in health care in 2017, more than three as much as Spain ($3,200) and Italy ($3,400). Many Americans postpone important medical operations for years, until they reach 65 years of age, when they finally qualify for universal health care or Medicare. Lack of prevention and primary care, health interventions postponed, and the constant worry that medical costs might bankrupt one’s family: none of this is conducive to healthy lives.

Who has not heard of the fabled “Mediterranean diet?” Rich in seafood, vegetables, olive oil and nuts, with little or no room for packaged and processed foods, it leads to lower rates of cardiovascular diseases and diabetes. Healthy dietary habits help propel Spain and Italy to the top of the Bloomberg health rankings, but they are not the only nations to eat well among the top 12 listed in the study: Israel is also a Mediterranean country, and its habitants’ culinary habits have a lot in common with those of countries bordering the Roman “Mare Nostrum.” They all share an abundance of high fiber and low-fat foods with plenty of the vegetables, fruits, organic products, and oily fish so good for weight control. And then there is Japan, 4th on the Bloomberg study, which can boast of legendary and centuries-old food traditions emphasizing balance, variety and freshness of ingredients. One very tangible result of all these culinary traditions is a much lower rate of obesity than in America. Obesity leads to a number of potential causes of premature death such as heart diseases (the leading cause of death in the U.S.), diabetes and kidney ailments. It is unfortunately a well-known fact that adult obesity in the U.S. exceeds that of most countries in the world, including all those ahead of us in the Bloomberg health rankings. About 40% of adults in the USA are obese, with a body mass index (BMI, a measure of a person’s weight relative to her or his height) above 30. In Spain, only 25% of adults have a BMI above 30; that percentage is 20% in Italy; and a remarkable 5% in Japan. The causes for obesity in America are well known: A poor diet, with too much consumption of packaged and processed food; too many fast food meals; and low levels of exercise due to excess driving caused by an urban sprawl absent in Europe and Japan. Bad diets are also a symptom of the growing economic inequality in the U.S. Fresh, natural and organic products are high-priced relative to packaged and processed alimentation: As a result bad nutrition affects disproportionately those at the bottom of our socio-economic pyramid, with very negative health consequences. Let’s now look at health crises that appear to afflict our country more than other developed economies. The first one that comes to mind is the opioid epidemic, now officially a national emergency. The U.S. accounts for 4% of the world’s population, but 27% of the world’s drug overdose fatalities, with 47,000 people dead from overdose in 2017. Why? Americans use more opioids than any other developed country: According to the United Nations International Narcotics Control Board, daily opioid use is twice as high in the U.S. as in Germany, the largest European economy. The difference is higher still with the nations ranked at the top of the Bloomberg Index: Italy; Spain; Iceland; Japan; Sweden; Norway; Israel; and France consume between 10% and 20% opioids per capita relative to the U.S. One of the main reasons is that physicians in the U.S. are much more willing to prescribe opioids to their patients. In particular, American doctors routinely prescribe insurance reimbursed opioids for chronic pain. In contrast, Japanese health insurers will not cover opioid consumption unless used in surgery at the hospital. In Europe, opioids may be reimbursed outside surgery but are generally prescribed by specialists rather than primary care physicians, and in hospital settings, a very controlled environment. The pharmaceutical industry is also much more regulated outside the U.S. Advertising for drugs in Europe is severely limited when not prohibited outright. In our country, thanks to their enormous and successful lobbying efforts, pharmaceutical companies are free to promote their products endlessly. American doctors prescribe 50% of the opioids consumed for use at home, according to the Center for Disease Control and Prevention: Prescribing opioids is easy, and takes little time for overburdened primary care physicians who may see as many as 30 patients per day. The much loved Japanese doctors calling on their patients at home have more time to engage in a more personal discussion with their patients, which might lead to a longer-term therapy alleviating pain without drug prescription. In Europe as well, physicians work with their patients to promote overall good health, nutrition and wellness, as alternatives to remedial drug use.

In another crisis, less remarked-upon than opioid abuse, we have experienced recently an alarming rise in suicides in the U.S. The number of suicides in our country rose 30% since 2000, reaching 43,000 deaths in 2017, or 13 per 100,000 people. This tragedy is afflicting disproportionately those in mid-life, between 45 to 54 years of age. It did not use to be this way; remember the stories about high rates of suicide in Nordic countries relative to ours? Yet, during the last 15-20 years, suicide rates fell in other developed countries, particularly in Europe: According to the World Health Organization (WHO),suicide rates are now at 5 per 100,000 in Spain, or less than half than in the U.S. In Denmark and Norway this rate is now at 9, and it is 11 in Sweden, all below ours. Are there explanations for this tragedy? This is obviously a very sad and sensitive topic, much beyond the scope of this article, but a number of studies have looked at economic and social causes for this affliction. Some evidence points to the weakening of the welfare safety net and social norms in the U.S. regarding mutual aid as one of the causes for this increasing despair in our population. Other studies blame widening income inequality, a distinctively American trend among developed nations: The Gini Index measuring inequality has risen to 0.4 in the U.S., versus 0.27-0.3 in European countries and Japan. Then there is the widespread availability of firearms in the U.S., with over 24,000 suicides per year in the country being committed with guns. On the other hand, all the top 20 healthiest countries in the Bloomberg study share a strong safety net, low economic inequality, and strict gun control laws. It is impossible to write about the lower life expectancy in the U.S. relative to the rest of the developed world without mentioning the 40,000 gun deaths we suffered in 2017. About 60% of these were suicides; and 40% homicides, or 4.4 deaths per 100,000 habitants. This is the one negative indicator where we are not two or three times worse than other developed economies, but an order of magnitude worse—10 times or more. According to the WHO, gun related homicides per 100,000 habitants total 0.47 in Canada; 0.15 in Denmark; 0.07 in Iceland; 0.06 in the United Kingdom; 0.04 in Japan; and 0.02 in Singapore. Clearly, the lack of gun control laws in our country leads to an actual national health emergency.When baby boomers were growing up, many enjoyed vacations in Europe. One frequent story told by our vacationers was the mortal danger of European roads, foremost in Italy, France and Spain. In contrast, European visitors to America marveled at the safety of our highways. Forty years later, these trends have inverted:U.S. road mortality reached 40,000 fatalities in 2017, representing 12 deaths per 100,000 habitants in our country, versus an average of 9 in Europe. According to the WHO, Italy is now at 6; Japan below 5; Spain below 4; and world road safety pacesetters Netherlands, Sweden and the U.K. at around 3. What are we doing wrong relative to these other countries? Here are a few hypotheses: Lower front seat belt use; higher rate of driving under influence; driving licenses available to 16 old youths, versus 18 elsewhere; and an increase of speed limits up to 85mph in some cases, in a country that has historically maintained very strict speed limits, at 55 mph in most places. The two leading causes of U.S. deaths are heart diseases (614,000 in 2017) and cancer (592,000). Respiratory diseases come next (147,000), with strokes representing 133,000 deaths. This is fairly typical among developed nations, although our rate of heart diseases is much higher than average—caused by the diet issues we saw above. What makes us unique among our economic peers is our high rate of accident casualties (136,000 in 2017) and suicides. These no longer make the top ten lists of causes of deaths in other developed countries.

With life expectancy declining in America during the last two years—a very undesirable type of “exceptionalism”—it is high noon for the U.S. public: We need to demand much more of our politicians, that they approve new laws giving us universal health care (e.g. though Medicare for All, with a public option available to everyone who wants it); stricter regulations of pharmaceutical companies; gun control; and a fairer economy. Individually, we also need to recognize the crucial roles of a healthy diet and wellness in a long and enjoyable life. Most medical professionals agree with these priorities, which are necessary to bring us back in line with developed world health statistics.

Author of “Untangling the USA: the Cost of Complexity, and What Can Be Done About It,” Etienne Deffarges has counseled, created, and invested in countless organizations during his professional life as a management consultant, business executive, and entrepreneur.

Article source:The Health Care Blog

0 notes

Text

Financial Toxicity is Hurting my Cancer Patients

By LEILA ALI-AKBARIAN MD, MPH

As news of Tom Brokaw’s cancer diagnosis spreads, so does his revelation that his cancer treatments cost nearly $10,000 per day. In spite of this devastating diagnosis, Mr. Brokaw is not taking his financial privilege for granted. He is using his voice to bring attention to the millions of Americans who are unable to afford their cancer treatments.

My patient Phil is among them. At a recent appointment, Phil mentioned that his wife has asked for divorce. When I inquired, he revealed a situation so common in oncology, we have a name for it: Financial Toxicity. This occurs when the burden of medical costs becomes so high, it worsens health and increases distress.

Phil, at the age of 53, suffers with the same type of bone cancer as Mr. Brokaw. Phil had to stop working because of treatments and increasing pain. His wife’s full time job was barely enough to support them. Even with health insurance, the medical bills were mounting. Many plans require co-pays of 20 percent or more of total costs, leading to insurmountable patient debt. Phil’s wife began to panic about their future and her debt inheritance. In spite of loving her husband, divorce has felt like the only solution to avoiding financial devastation.

Sadly, as healthcare costs rise, more Americans find themselves in similar situations. The United States spends more on healthcare than any other nation, without better results. Uncontrolled costs waste money and may be worsening the health of cancer patients. An astounding 30 percent of advanced cancer patients reported financial distress higher than physical or emotional distress. In these cases, the cost of care was literally more toxic than the effects of cancer or cancer treatment.

Yet, oncology care can be delivered for far less money. The American Society of Clinical Oncology found that the costs of treating metastatic colon cancer in Washington State vs. British Columbia was double in the US compared to Canada, with similar outcomes. American doctors provide some of the highest quality medicine in the world, but the associated costs are neither affordable nor sustainable.

Much of this financial toxicity could be eliminated with a single payer system. Such a system would reduce the administrative costs associated with the ‘business of medicine’ — costs accounting for 25 percent of American healthcare charges. Additionally, small companies would not be responsible for expensive healthcare benefits, and citizens could endure job change more safely. A single payer system would also allow medical providers to get paid appropriately for services, but industry CEOs could no longer inflate costs in a market that profits from the sickest and most vulnerable Americans.

Healthcare as a private enterprise is hurting people like Phil and his wife. It is increasing the suffering of cancer patients. The Canadians have proven that the same care can be delivered at half the cost. It’s time to put politics aside and move forward with a similarly designed system, with the goal of improving the health of Americans without the toxic burden of medical debt.

Dr. Leila Ali-Akbarian is a Public Voices Fellow and a primary care physician who practices Cancer Survivorship and Palliative Care at the Banner-University of Arizona Cancer Center.

Article source:The Health Care Blog

0 notes

Text

Six Health-Focused Fixes for SNAP

By CHRISTINA BADARACCO

The $867 billion Farm Bill squeaked through our polarized Congress at the end of last year, though it was nearly derailed by arguments over work requirements for SNAP recipients. That debate was tabled after the USDA crafted a compromise, but it is sure to continue at the state level and in the next round of debates. While Republicans tend to favor work requirements and Democrats tend to oppose them, here’s something both sides can agree on: SNAP should help Americans eat healthy food.

The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP)—formerly known as food stamps—provides financial resources to buy food and nutrition education to some 40 million low-income Americans. Costing taxpayers almost $80 billion per year, the program serves Americans across the spectrum of ages, ethnicities, and zip codes. Simultaneously, we reached a deficit of almost $800 billion in 2018. So how can we ensure this at-risk population of Americans can access nutritious food and better health outcomes within the confines of our current resources?

Studies have proven time and again how participation in SNAP reduces rates of poverty and food insecurity. And the program has improved substantially in recent years, with recipients now using debit-style cards to buy groceries and receiving increased benefits at thousands of farmers markets across the country.

Despite these clear benefits, SNAP dollars often don’t support healthy diets. In fact, a 2015 study determined that SNAP participants had poorer diets, with more empty calories and less fresh produce, than income-eligible non-participants. In 2017, another study found that participants have an increased risk of death due to diet-related disease than non-participants. The authors reported that the discrepancy might be partly caused by individuals who think they have high risk of poor health and/or struggle to pay medical bills are more likely to put in the effort to enroll in and redeem SNAP benefits. A recent survey of Americans across the country showed that foods purchased using SNAP benefits were higher in calories and unhealthy components, like processed meat and sweeteners, than those purchased by non-participants of the same income level.

What’s going on? As a dietitian, my previous work with low-income patients at a prominent Boston hospital opened my eyes to the numerous barriers many of them face in following a healthy diet. My role involved counseling patients ever-so-briefly on improving their diets and checking boxes on a computer screen to send them on their way to receive their nutrition assistance benefits.

Many low-income residents live far away from high-quality grocery stores and farmers’ markets, and lack a consistent or safe way to get there. They can’t afford some of the most nutritious and fresh foods, and/or lack time to prepare meals from scratch. So, they end up getting the most calories for their dollar by eating energy-dense fried fast food or frozen foods, ready to fill a hungry belly at a moment’s notice. Indeed, the SNAP allotment falls just above $2 per person per meal (for the highest earning single person). This population has a higher risk of being overweight and sick because unhealthy food is cheaper and more widely available. But the reason why diet and health are in many ways worse among recipients compared to others at a similar income level warrants further study; indeed, this is an area that researchers continue to investigate.

Moving forward, we need to ensure that SNAP helps struggling Americans eat food that is actually good for them and promotes good health, supporting family life and preparation for the working world. Here are six suggestions for future farm bills:

Prescribe produce. Because the majority of SNAP households have at least one member on Medicaid or the Children’s Health Improvement Program (CHIP), integrating a healthy food prescription program and more robust nutrition education for these recipients as part of Medicaid could better promote shared health outcomes. The bipartisan Food is Medicine Working Group, founded in early 2018, was instrumental in integrating language about a pilot produce prescription program into the recently-passed Farm Bill. That pilot can yield real data about the health benefits of such programs, which can then be expanded based on justifiable outcomes. Connecting health and nutrition via enrollment in federal programs provides a unique opportunity to drive progress.

Make shopping safe. Given that public health research has shown strong associations between community violence and food insecurity, attempts to increase food access must focus on improving safe access. Farmers’ markets and healthy corner stores receiving funding through the Healthy Food Financing Initiative (HFFI) can be incentivized to open at police stations or schools, with built-in added security to allow families to use their benefits.

Leverage purchasing power. Expand funding for food hubs through the Local Food Promotion Program to support centralized purchasing of healthy staples for SNAP recipients within concentrated communities of beneficiaries to lower marginal costs and increase access. Food could be distributed to community centers via a model like a community supported agriculture (CSA) or meat share.

Incentivize healthy eating. It’s possible to improve diets without substantially increasing costs by expanding incentives for buying healthy foods and adding disincentives for unhealthy foods. Thousands of farmers’ markets currently offer double dollars incentive programs—funded through Food Insecurity Nutrition Incentives (FINI) and/or philanthropy—so expanding this beyond farmers’ markets could make a huge impact.

Connect growers and eaters. Better connecting SNAP recipients to urban agriculture or community gardens can address the lack of understanding among Americans about where and how food is grown while also promoting local food production. This could involve expanding the jurisdiction of the Food and Agricultural Service Learning Program (FASLP) beyond children to include adults using SNAP.

Teach food literacy. SNAP-Ed can be a valuable tool to teach basic nutrition to recipients, but is wholly underutilized and should focus on teaching more hands-on cooking skills to people without basic food literacy. This is critical at a time when Americans spend less time than ever preparing food. Emphasizing or incentivizing programming in teaching kitchens—perhaps in existing schools or community centers, where families can receive a meal and learn hands-on skills—may translate to improved home cooking skills.

Debates over the next Farm Bill are sure to be as contentious as the last. But policymakers across the political spectrum can agree that our tax dollars should support better health and nutrition for SNAP recipients. Implementing these solutions can improve the diets of SNAP recipients, with a longer-term benefit of boosting health and reducing healthcare costs. That will require better cooperation across programs, creativity on the part of state agencies administering these programs, and reprioritizing programs and dollars to support health outcomes.

—

Christina Badaracco is a registered dietitian who writes regularly about food, agriculture, and public health. She is the co-author of The Farm Bill: A Citizen’s Guide (Island Press, 2019).

Article source:The Health Care Blog

0 notes

Text

The Next Frontier: Clinically Driven, Employer-Customized Care

Health systems and employers are bypassing insurers to deliver higher-quality, more affordable care

By MICHAEL J. ALKIRE

Employee health plan premiums are rising along with the total healthcare spending tab, spurring employers to rethink their benefits design strategy. Footing the tab, employers are becoming a more active and forceful driver in managing wellness, seeking healthcare partners that can keep their workforce healthy through affordable, convenient care.

Likewise, as health systems assume accountability for the health of their communities, a market has been born that is ripe for new partnerships between local health systems and national employers in their community to resourcefully and effectively manage wellness and overall healthcare costs. Together, they are bypassing traditional third-party payers to pursue a new type of healthcare financing and delivery model.

While just 3 percent of self-insured employers are contracting directly with health systems today, dodging third parties to redesign employee benefit and care plans is becoming increasingly popular. AdventHealth in Florida announced a partnership with Disney in 2018 to provide health benefits to Disney employees at a lower cost in exchange for taking on some risk, and Henry Ford Health System has a multi-year, risk-based contract with General Motors.

The notion of bypassing payers is attractive for employers, especially on the back of consecutive cost increases they and their employees have swallowed over the last several years. Payers have traditionally offered employers rigid, fee-for-service plans that not only provide little room for customization, but often exacerbate issues with care coordination and lead to suboptimal health outcomes for both employees and their families. Adding to this frustration for employers is the need to manage complex benefits packages and their corresponding administrative burdens.

The direct-to-employer model is necessary, but hard to get right

In a direct-to-employer contract, a health system partners with an employer to create a customized health plan that is based on predictable outcomes and provides healthcare services that span the continuum of care, from primary care and inpatient stays to rehabilitation. These arrangements allow employers to work directly with health systems to share in the cost and quality gains that come from improved outcomes. One major pro is that the health system owns the employee health data, unlike in managed care arrangements.

While today’s claims data is often held ransom by third-party payers, direct-to-employer plans create actionable insights for providers. The increased transparency into claims information enables health systems to deliver the most appropriate care using evidence-based practices. This allows them to digitally monitor at-risk employees; easily measure, track and compare progress; and engage in more coordinated care practices to improve outcomes and reduce variation and waste.