Text

Book Review: "The Effective Judicial Prosecution of Systemic Political Corruption: Italy" (Manzi, 2018)

Source: 'Mani Pulite,' Investigation in Italy Film (1992)

Before populists Silvio Berlusconi and Matteo Salvini came into the political landscape of Italy, there was a hidden, dirty system running rampant through the political parties and actors. The system was a corruption system that would later put nearly every national politician in Rome in handcuffs. This investigation was called “Clean Hands,” and as the name implies, it was the purification of the Italian political landscape and the fall of the “First Republic” of Italy after 50 years of governance.

Luca Manzi, the author of “The Effective Judicial Prosecution of Systemic Political Corruption: Italy,” is an Italian writer and media consultant. This text is considered a dissertation, but the dissertation is organized into chapters. Manzi’s thesis for this dissertation is an analysis of how Italy effectively promoted the judicial persecution of the top political actors on the grounds of corruption. Also, how egalitarian governance positively affects judicial professionals’ conviction rates, legal knowledge, and collaboration among each other.

Manzi states that there are two types of judicial governance: bureaucratic and egalitarian. Bureaucratic governance is essentially where only a few judges have the power to make policies and decisions on cases. In a bureaucratic governance, there is little to no room to learn or change judicial precedents. The older, high-rank officials make all decisions with no advice from lower-ranked judges or prosecutors. Egalitarian governance is “an organizational structure that requires an assignment of all cases that are related to the same criminal issue to a group of judiciary professionals, treating each other as peers and handling the workload and information together,” (Manzi, 2018). Egalitarian governance focuses on collaboration and the learning process, where younger or lower-ranked judiciary professionals can learn how to accurately prosecute complex criminal issues, such as corruption. Prior to the 1970s, the Italian judicial system had bureaucratic governance, until Milan and Turin's courthouses started moving towards egalitarian governance.

The author develops his theory by breaking his dissertation into chapters. He first starts off the book with what exactly he is going to be analyzing. Manzi gives a run-down of the political system and judicial system of Italy, as well as how long corruption has been seen in Italy. Manzi also brings in opinions from other scholars on why they think Italy was able to successfully prosecute high-powered politicians and prominent businessmen, such as Della Porta, Pederozli, and Nelken. Finally, Manzi defines what he called judicial effectiveness. In the next chapter, Manzi organizes his theory, while labeling his dependent and independent variables for his analysis of different regions in Italy. The third chapter is where Manzi defines key terms for his argument, such as “flattening” and “hierarchical” judiciary systems, as well as a history of the “First Republic,” leading up to the Clean Hands investigation. The next chapter focuses on the case studies of Rome and Milan as they go through the learning process of egalitarian governance, as opposed to the old hierarchical system. This is where the book showcases how Milan and Rome are different in terms of egalitarian governance, the professional relationships between judiciary actors, and why Milan was more successful in the persecution of the Clean Hands suspects than Rome was.

This book has extreme importance to a political concept brought up in class. We’ve spoken plenty about the corruption in many countries with populist actors. In Germany, political parties and businesses are the most corrupt institutions (Transparency International 2013). Donald Trump had continually abused his power as the executive leader of the United States by having the government pay him over $1.5 million for the Secret Services’ use of a private plane during a campaign, as well as receiving an unlimited amount of donations from wealthy individuals and corporations- reportedly more than $107 million and some of that money is unaccounted for (Berger, Kennedy, Pilipenko, 2018). As this book shows, Italy is no different. The leader of the then-Socialist Party, Mario Chiesa, had been arrested on charges of corruption for accepting a bribe from a company manager. This arrest was the start of unraveling the corruption system that involved nearly all national political parties, politicians, and businessmen. Throughout this analysis, there are many times the author points out that the Italian judiciary system found out about the corruption system but, due to the hierarchical structure of the courts and the superior judges not getting along with lower-ranked and younger judges, refused to do anything about it. This was in large part due to the professional and close relations with the high-rank judges and national politicians. It is not until the Milanese and Turin courts “flatten” their judicial structure that the corrupted politicians are given justice for their crimes.

The diffusion from hierarchical, bureaucratic governance to egalitarian governance was a crucial part of the Clean Hands investigation. In Milan, the state prosecutor, Mauro Gretsi, was the first Italian judicial professional to implement egalitarian governance. His subordinates described Gretsi as an “enlightened conservative,” as he would hold regular meetings with the prosecutors working in his office, (Spataro 2011) and listened to what his subordinates suggested. Gretsi took the suggestions he received seriously, so much so that when a younger prosecutor suggested a terrorism judicial team, Gretsi created it. This caused, what Mainwaring and Perez-Linam called, the “demonstration effect.” The demonstration effect is defined as “when there is a successful prosecution of a specific criminal issue in one jurisdiction that might promote an increase in the number of trials for the same criminal issues across jurisdictions,” (Mainwaring and Perez-Linam, 2013). Essentially, the demonstration effect is like the domino effect, where one courthouse does something, and the rest will follow.

Well, everyone except for Rome. Manzi argues that the “hierarchical judiciary structure of professional relationships within key judicial players in Rome can prevent effective prosecution of complex criminal issues,” (2018). In Rome, working in the prosecutor’s office or in the court system was very hostile for younger or low-ranked judiciary actors. The higher-rank judges had full control and power over the low-rank judges and rarely let the low-rank judges give suggestions on cases. This, in turn, creates plenty of unknowledgeable judges presiding over cases and high-ranked judges a sense of dictatorship in the judicial system. For example, when members of a left-wing terrorist group, the Red Brigades, were tried in a courtroom in Turin, the group claimed that they had kidnapped and killed Christian Democracy's leader, Aldo Moro in 1978. Moro lived in Rome, as did the rest of the national government officials. Even with the clear indication that the Turin case and the murder case in Rome were connected, there was no willingness by Roman high-rank judiciary officials to get justice for the slain Christian Democracy leader, even with objections from the lower-rank officials. Rome continued with its hierarchical structure to keep the national politicians happy, even if it meant turning a blind eye to murder or corruption in national politics.

The Clean Hands investigation was the most polarizing scandal in Italian history. The investigation revealed a secret society, political and mafia relations, and political corruption all the way to the federal level. The arrest of Mario Chiesa was the flame that lit the fire. The main prosecutor for the investigation was Antonio Di Pietro. He had been involved in this investigation from the start. Once Chiesa testified, Di Pietro realized how intricate this corruption system was. Chiesa testified stating which companies he received money from and mentioned several socialist politicians who had given him bribes as well. On top of that, he describes the rules and functions of this corruption system and incriminates several of the system’s members. After Chiesa’s testimony, a “prisoner’s dilemma” began, in which many politicians and prominent businessmen came forward stating they were a part of the corruption system to receive less of a penalty, or dodge corruption charges altogether (Della Porta 2001). Cooperation in this investigation was always rewarded.

The implementation of egalitarian governance helped this investigation to achieve the highest level of judicial effectiveness. One of the prosecutors, Colombo stated that he had “accumulated a significant amount of expertise in the effective prosecution of financial crimes, expertise which he had shared with other participants in the judicial network,” (Manzi, 2018). This governance also helped judges collaborate with each other without fear of expressing their own opinion on the matter. The implementation of egalitarian governance has a lasting impact on judicial professionals in terms of collaboration, knowledge, and successful prosecution.

I believe this book achieves its goal of analyzing how Italy effectively promoted judicial persecution of the political actors involved in the Clean Hands investigation. By comparing case studies in Rome and Turin/Milan, it shows an extreme difference in what egalitarian governance can do for the judicial system and their prosecutions of complex criminal matters. In Milan and Turin, implementing egalitarian governance helped prosecutors and judges to find the most intricate corruption scandal in Italian history, as well as the knowledge and ability to fully persecute these politicians of the law, due to their collaboration with each other. In Rome, the hierarchical structure limits what the judicial professional can learn and prosecute, as it is only the high-ranked officials that are allowed to express opinions and make the decisions. There is a clear indication through these case studies that egalitarian governance gets the judiciary actors the best results in terms of persecutions, convictions, legal expertise, and collaboration.

0 notes

Text

Book Review- From Rhetoric to Reality: The policy and practice of women's rights in Italy (Montoya-Kirk, 2005)

Source: Andrew Medichini | AP

Italy is best known for its beautiful architecture, scenery, food, and wines. The country is also known to have a strong connection with the Vatican, making its societal norms more traditional than the rest of Europe. One conservative value many Italians share with the Catholic Church and the Pope is the traditional role of women as domestic workers, the denial of abortion and contraceptives, and turning a blind eye to violence against women. Celeste Montoya-Kirk, a political science and gender studies professor at the University of Colorado Boulder, has taken it upon herself to analyze the women’s rights legislations of Italy compared to western Europe and internationally. Here, we find that even though Italy’s women’s rights policies are exemplary compared to the rest of the world, the implementation of said policies has tarnished Italy’s status as the most progressive in women’s reproductive rights. Montoya-Kirk has written a handful of texts consisting of women’s rights, feminism, and how certain countries compared to the rest of the world in terms of women’s rights policies, making her an ideal scholar to analyze such a topic. The text is named ‘From rhetoric to reality: The policy and practice of women’s rights in Italy,’ published in 2005. The text is a dissertation written in a book form, with six chapters.

There are three main themes of this dissertation. The first theme is that the author argues that the formation and creation of women’s rights policies are not a good measure of improved gendered discrimination and women’s rights because these policies are being created for other reasons, not to see the improvement in women’s rights. For example, many countries, including Italy, have passed women’s rights policies so that they are conforming to the global norms found in other countries. Another major theme in this book is women’s rights policy legislation. Women’s rights legislation in Italy is, as Montoya-Kirk puts it, exemplary compared to the rest of Western Europe. Italy has passed anti-discrimination laws, as well as positive action policies and reconciliation provisions (Montoya-Kirk, 2005). Reproductive rights policies allow for the creation of state-provided family planning counseling, free contraceptives, and free abortions for several reasons. Violence against women in Italy has become more comprehensive in terms of domestic abuse, sexual assault, sex trafficking, and marital rape policies. Italy has become relatively progressive in terms of women’s rights policies, especially with the Catholic Church’s heavy influence on the government and society. The third theme of this reading is that even though Italy has passed progressive women’s rights policies, the implementation process of these policies is not exemplary. The implementation of these policies is deemed “inconsistent and problematic,” (Montoya-Kirk, 2005). For example, Law 903 was passed in December of 1977. The law was named “Equal Treatment for Men and Women as Regards Employment.” This legislation put Italy in compliance with the European Union’s Equal Pay and Equal Treatment Directives. This is a prime example of a country creating a women’s rights policy due to global norms- not because they want to see change. This act prohibits any discriminatory acts because of a person’s sex, marital status, and pregnancy. Though this law was a good starting point for equality in the workplace, the law is “vaguely written and provides loopholes for interpretation,” (Collins, 1992). The themes of this article are that the creation of women’s rights policies does not always mean society has completely fixed gender discrimination, even if the country- like Italy- has exemplary policies.

The dissertation developed its theory and arguments in a unique way. She begins by defining women’s rights and feminism. She then begins to explain the framework for women’s rights policy, including how social norms frame women’s rights. Montoya-Kirk also introduces her data and sources before starting her in-depth analysis of Italian women’s rights and policies. Once she has defined and explained how she framed her work, she begins a cycle of history behind each women’s rights issue (employment rights, abortion/contraceptive, and violence against women), the types of different policies for each women’s rights issue, how the international, European, and Italian sphere deals with the women’s reproductive rights agenda, and finally what policies Italy has implemented to better employment rights for women, abortion and sex education, and violence against women. Each chapter in the book looks at one specific women’s rights issue and continues the cycle explained above at the start of each chapter, using other scholars and other data to verify and justify her claims.

This text helps us understand how social norms affect social and public policies. Italy has close connections with the Vatican, which tends to have very conservative views on women’s rights like abortion and contraceptives. The Catholic Church, along with Christianity and Islam, believes sexual intercourse should only be between a married couple- specifically heterosexual couples. On top of this idea, the Church also argues there should be no use of physical contraceptives during sex. Abortion was written in the first penal code of the Italian Republic as murder, which took after the Catholic Church’s view as abortion is murder. On top of this, Italy has created state-run family planning centers that can provide safe and free abortions, as well as contraceptives. However, there are limitations to abortion. Abortion is only legal for the first trimester of pregnancy. After the first trimester, the only reason a woman can get an abortion is if she is at serious risk physically or mentally. The woman must submit a request for an abortion to the state-run family center or go to a primary care physician. 7 out of 10 primary care physicians and gynecologists in Italy refuse to perform abortions, which is an issue when there are only 3,000 state-run family centers in Italy (NBC, 2016). The close bond of Italian citizens, government, and the Vatican cause the societal morals of Italy to take over instead of the public health of pregnant women. Italian culture also heavily emphasizes family, with the mother at the center of it. Women in Italian culture are seen as maternal and need to be protected. They are valued as homemakers, not as a worker.

Another reason this text is important is this text helps us understand the effects political parties in power have on policies involving women’s rights. For example, during the Olive Branch Coalition, led by Romano Prodi, there were massive amounts of change and progress for the women’s rights movement. For example, more women were elected to office, women were put in charge of important ministries like the Home Office, Health and Social Affairs, and the Minister of Equal Opportunities. Then, when Italy rescinded back to Berlusconi’s leadership, there was a decrease in progress for this movement. Berlusconi disbanded the National Commission for Equality and Equal Opportunities, which was a major committee dedicated to spreading awareness of inequality in the workplace. The dissertation helps to show how social norms, political parties, and Italian culture affect social and public policies.

I do believe this book achieves its goal of finding out if progressive women’s rights policies showcase improve gender discrimination and women’s reproductive rights. Though Italy has some of the most progressive women’s rights policies in Western Europe, the country has not been able to implement the policies effectively. This failure to implement has caused Italy to fall behind in terms of gender policies in the rest of Europe.

I believe the book adds value to understanding important issues. Societal norms play a massive role in how society views a certain social/public policy or issue. Due to the largely Catholic, patriarchal society Italy has, many Italians believe that women’s rights issues are not a prominent or urgent issue to fix. Abortion is one of the most controversial women’s rights issues in terms of these social norms, as the Catholic Church and its active followers argue that an embryo is a human soul that needs to be protected by the evils of abortion. Another way this book adds value to these issues is using comparing Italy to other European countries and European Union policies. The comparison of these countries to Italy helps portray Italy as exemplary in the creation of women’s rights legislation but also portrays Italy as a poor implementer of these legislations. Finally, another important issue this book helps add value to is the length of time Italian women, and women in other countries as well, have been advocating for their rights. The first feminist wave was in the late 1800s, with the second and much more aggressive wave in the 1970s. During the 1970s, women across the world advocated for their right to equality, their right of choice, and their right to not be discriminated against. To this day, nearly 130 years later, Italian women and other women have been fighting to get the same pay wage as their male counterparts, to be seen as equal to their male counterparts, and for their right to choose what they can do with their body or how they want to parent (or even have) their kids.

The strength of this book is how well organized and in-depth the book is written. With sections clearly labeled with titles that provide a brief overview of the section, it is easy to understand and interpret what is being analyzed. The depth of this book is, I argue, its greatest strength. The author not only looks at Italy’s women’s rights legislation, organizations, and politicians, but also investigates the European Union’s women’s rights legislation as well as international women’s rights legislation so the reader can fully grasp just how exemplary Italy’s women’s rights legislations are. Also, the breakdown of each type of approach to women’s rights issues and definitions of each helps the reader fully understand what exactly feminism, abortion, women’s rights, violence against women, and employment in the workplace truly are.

The weakness of this book is that it gets repetitive in terms of how it's organized. The need for defining each women’s rights issue the author talks about, the approaches she is going to take in analyzing it, and the repetitive use of the same scholars make it hard to stay focused on the reading.

This book was well-crafted and impactful. Like I said above, the way it is organized is very helpful and well-crafted- even if it is repetitive. This book was impactful as it gave me more positive insight into Italy’s politics and society than the populist leaders of Italy have shown me. The fact that Italy is one of the most progressive in women’s rights legislation was a breath of fresh air compared to the constant corruption, crimes, and racism seen by populist leaders like Matteo Salvini and Silvio Berlusconi.

Overall, this book was well written, well defined, and analyzed crucial parts of Italy’s women’s rights policies and movements. The use of European Union policies to demonstrate how Italy is considered progressive compared to other countries in the EU and the comparison of different political parties and their effect on women’s rights legislation helps to better understand Italy, its societal norms, political differences, and religious background.

0 notes

Photo

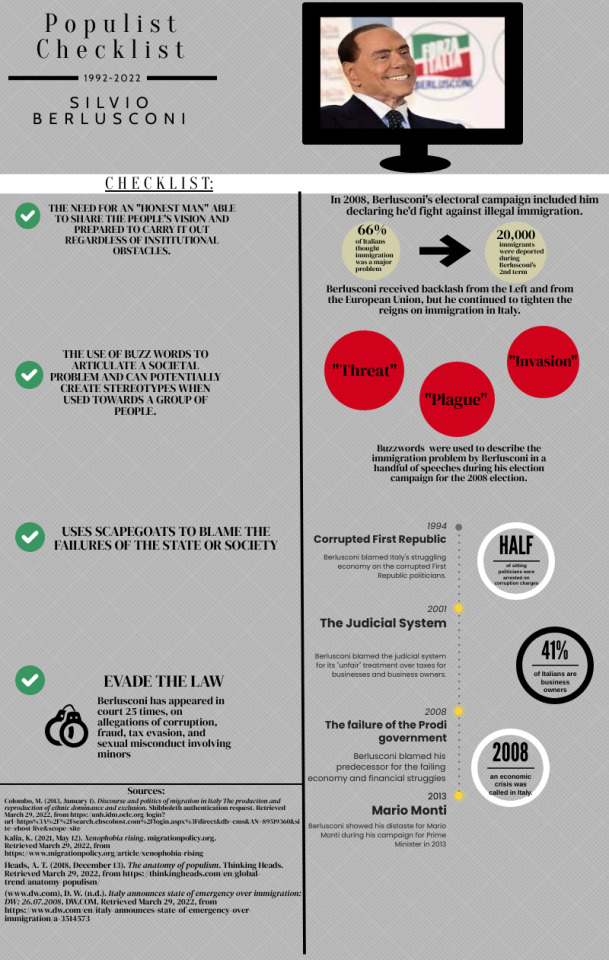

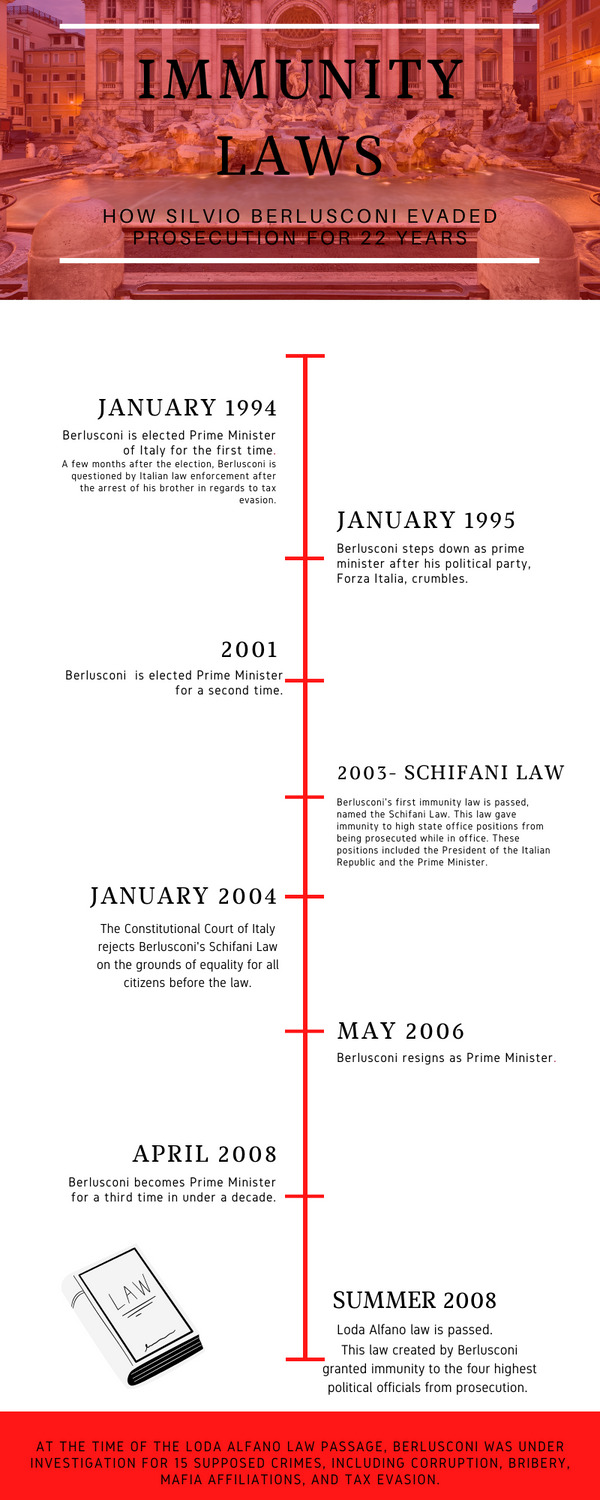

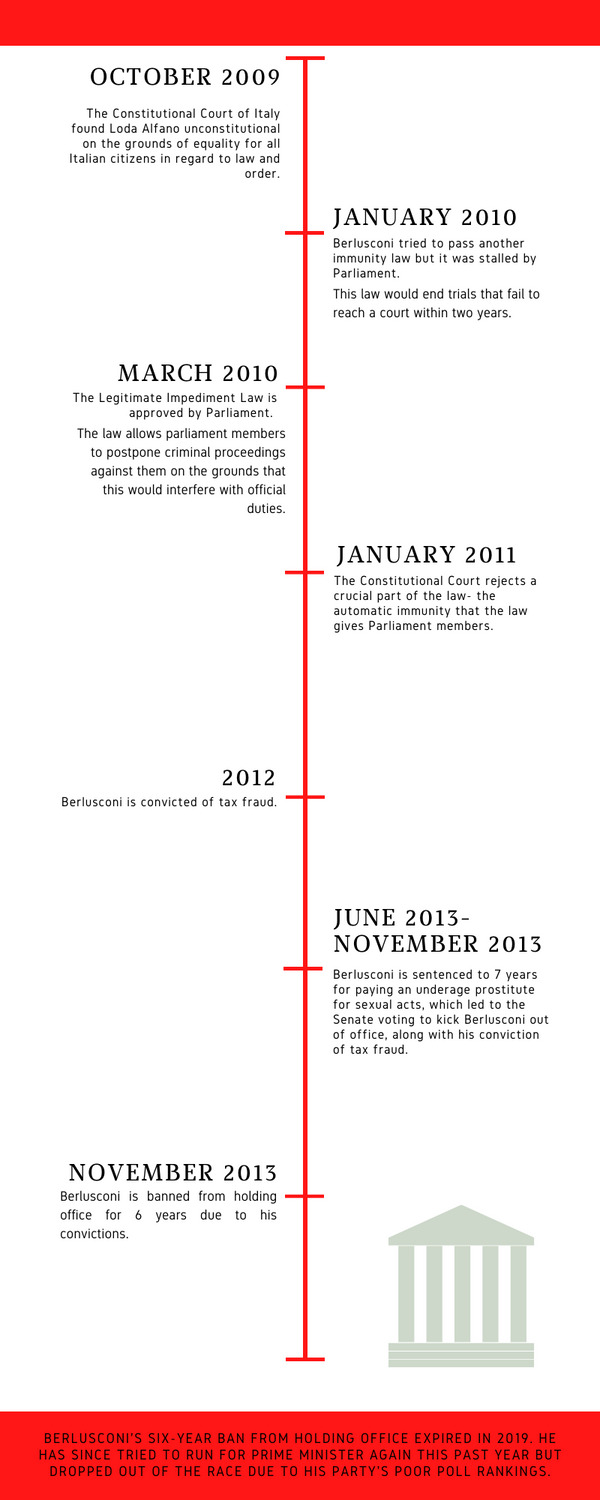

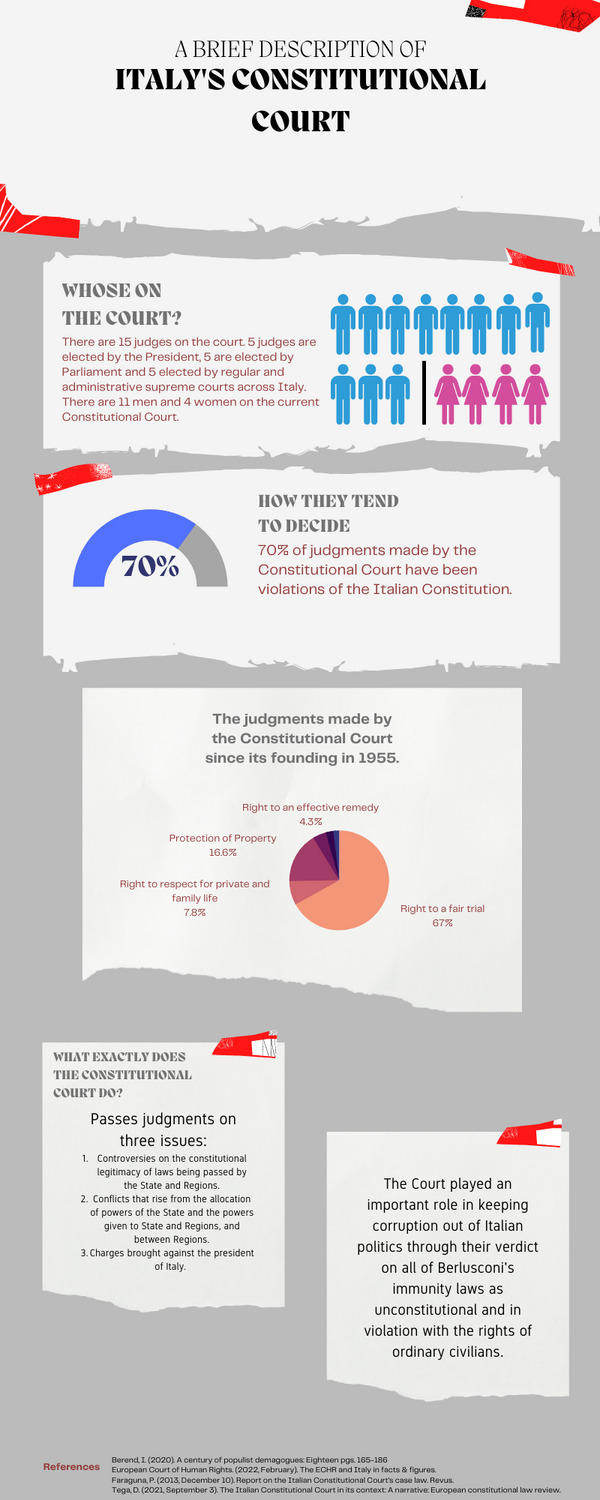

Timeline infographic of Silvio Berlusconi attempting to create laws that benefit himself and not others.

0 notes

Text

Scandal-Ridden Former Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi to Run for President in 2022

Source: REUTERS/REMO CASILLI

Silvio Berlusconi is a media tycoon turned former prime minister of Italy. His political track record is nothing less than mediocre. Scandals, corruption, fraud, and convictions riddle his political portfolio. But, he's back from house arrest and medical problems to once again run for prime minister of Italy this year.

Silvio Berlusconi was an Italian media tycoon turned prime minister He was prime minister for three terms: 1994-1996, 2001-2006, and more recently 2008-2011. The political group he belongs to is Forza Italia, which he founded in 1994. Berlusconi became a real-estate developer, earning a pretty hefty fortune by the 1970s. He created the cable TV company, Telemilano in 1974. In 1980 he established Canale 5, Italy’s first-ever commercial television network. When he founded Forza Italia in 1994, it was coined a conservative political party. That same year he was elected prime minister. Though that didn’t last long, as the Northern League decided to launch an investigation into Berlusconi’s business empire. Berlusconi stepped down as prime minister in 1994 but stayed on in a caretaker capacity until 1995. Once the investigation had ended, Berlusconi was convicted of fraud and corruption, but the verdicts would eventually be overturned.

Despite all of his legal issues, Silvio managed to remain the leader of Forza Italia, where he promised tax cuts, more jobs, and higher pensions. Due to these promises, he was elected prime minister again in 2001. But, after facing massive criticism from his constituents over sending troops to fight in Iraq and Italy’s struggling economy, once again Berlusconi stepped down.

He ran for reelection again in 2006 but lost to Romano Prodi. Then, two years later, Berlusconi ran yet again and won. He was then a member of a different political party, the People of Freedom, which was a center-right political group.

Berlusconi just couldn’t seem to stay away from more scandals during this third term. In 2009, Berlusconi was reportedly involved in a sex scandal, including alleged involvement with a minor. In 2011, he was ordered by the Italian government to stand trial for his alleged solicitation for sex from a 17-year-old prostitute, but it was dismissed.

Due to the Euro economic crisis in 2011, many politicians urged Berlusconi to step down as prime minister, which he obliged on November 12th.

Forza Italia and Berlusconi relied heavily on the use of media campaigns, particularly in television. Italy is a “television-centered” country, which means Italian citizens often consume news and media on a TV screen instead of other forms of digital media. This is a strategic, planned out tactic done by Berlusconi to get his messages and rhetoric to a massive amount of people, as he knows that majority of Italians watch TV for their news and information. It also helps that Berlusconi owns two of the biggest, most popular television networks in Italy. These media campaigns, and Italians knowing Silvio Berlusconi due to his huge level of success in the business world, is what helped Berlusconi and Forza Italia come to power in just a year after the political party was formed in 1993.

When Berlusconi first introduced his new political party in 1994, he gave a speech that showed he was already appealing to the people: “...that of uniting people, in order at least to give Italy a majority and a government that is up to the job of meeting the most deeply felt needs of ordinary people.” (Berlusconi, 1994). Berlusconi showed early on his populist ideologies, where he is a leader of the people to fight the evil of the old government and other coalitions in Italy.

Berlusconi continually pushed to use his political parties, Forza Italia and the People of Freedom, as a step stool for power. Like we have seen with George Wallace, populist actors tend to not want political change but political power. Populists tend to run campaigns based on what they know the people want to hear and will get them votes. Berlusconi was a media mogul who knew how to use media and speeches to get his popular vote up, manipulating the system and the people he claimed to care for.

Berlusconi wanted a strong reform of government, wanting Italy to move from a parliamentary system to a semi-presidential system, build a higher election threshold, abolish the Senate, and downsize the Chamber of Deputies. All these reforms would offer the prime minister more power than the parliament and would allow himself to have more power, in a typical populist fashion.

The construction of ‘vox populi’ consists of two processes, (1) the populist leader’s separation from the corrupted elites and (2) the populist’s connection to the people (Mudde and Kaltwasser, 2017). Berlusconi displays his separation from the elites through his speeches and rhetoric during his campaigns. He considered himself a “self-made billionaire who would sweep away a rotten political class and bring his business skills to running the nation” (Sylvers, 2018, paragraph 4). He identifies that he is a billionaire but is running for the prime minister not because he wants power or money (because he already has both) but because he wants to help get rid of the corrupted politicians that are controlling the Italian government. He sets himself apart from the other elites in government because he is a skillful businessman who can help Italy out of its economic recession and run the nation successfully.

In the Mudde and Kaltwasser reading, they spoke on how entrepreneurs were common but mostly ignored populist leaders. This story is depicted as the successful businessman, who had family fortunes, becoming the voice of the common people (Mudde and Kaltwasser, 2018, 70). The Berlusconi family is the sixth richest family in Italy, with $7.8 billion to their name. We also see this in Donald Trump, who is a successful business mogul with generational wealth, who played on the “true people’s” unhappiness with the Obama administration. Mudde and Kaltwasser argue that, though the entrepreneur-populist is not always easy to get votes, the populists use their construction as a political outsider to win votes (Mudde and Kaltwasser, 2017, 71).

Berlusconi also shows his connection to the people in many different ways. He says he is “the authentic voice of ordinary Italians struggling with high taxes and bureaucracy and dismissed- including many in the foreign media- as communists” (Sylvers, 2018, paragraph 4). Berlusconi argued he would lower taxes for everyone and reform their government, as spoken about early, through relieving the power the Senate has on Italian lawmaking and giving more power to the people’s votes. He also promised to create more jobs for the struggling Italians.

As a media tycoon, Silvio Berlusconi had a tight grip on the Italian media outlets. He owns Italy’s top three national TV channels. With that much power over the media, it surely affected the outcome of some of the elections he’s won.

According to Open Society Foundations, Mediaset and Rai (both owned by the Berlusconi family) control about 90% of the national audience and advertising revenue shares. With this massive amount of the population watching the TV channels, it’s easy to see why Berlusconi has been so successful in politics. And in controlling the media. As spoken about in the media landscape brief, it is not uncommon for populist actors in Italy to attack, threaten, and sue the media. Berlusconi, having built his fortune through the media, has tried extremely hard to put a muzzle on opposing news corporations to avoid scrutiny or from ruining his reputation, especially during campaign years. In 2009, Berlusconi sued the left-leaning, La Repubblica for libel over their publications of ten questions for Berlusconi and his relationship with a minor. Also in 2009, the Italian parliament (and Berlusconi) approved a government proposal to re-instate the criminal offense of insulting public officials (Pavli, 2010). This is a direct violation of freedom of speech in Italy.

Berlusconi also uses media to his advantage. Berlusconi recently announced he will be running for prime minister again in January of this year. Using his media channels, the channels have been promoting his “presidential ambitions, highlighting his qualities and achievements, and ignoring blemishes” (Jones, 2022) such as his legal troubles. His family-owned newspaper, Il Giornale ran an advertisement that said “Who is Silvio Berlusconi…who better than him?” that described his qualities, such as being a good and generous person, a friend of the world, and having no enemies. As well as the populist sentiment of a self-made man for all Italians. Berlusconi, also, hopped on the bandwagon of Instagram back in 2015, where he posted nearly 60 posts on the first day. As an older man, he is trying to get the attention of the younger generations, like the former prime minister Matteo Renzi.

Silvio Berlusconi has a long record of populist sentiments, law-breaking, and empty promises. With the presidential election in Italy coming up later this year, Berlusconi will try to win so he can run for another term, making it 5 terms as prime minister.

0 notes

Text

An Open Letter to the Anti-Immigrant Populist Party of Italy

Credit: Lega Nord, 2018

Dear Matteo Salvini and the Northern League,

Hi, Matteo and fellow Northern League supporters, I’m Kayla DeMarino and as an Italian-American, whose great-grandparents fled Italy back in the 1920s, I always wondered why they left Italy. Italy always seemed so beautiful and rich in history. The grand architecture, the amazing artwork, the delicious food all pointed to a rather delightful place to live. That was until I stumbled upon the populist party that is the Northern League. The anti-immigration laws you had put into place when you, Matteo, were deputy prime minister and the anti-immigration rhetoric that is spewed with hatred by yourself, and your racist party is honestly quite shocking.

Do you think less of Muslims? Because your policies say so. You made it compulsory for Muslims to celebrate rites in Italian, not their own language (which was not made compulsory for any other religions in Italy). You also made it mandatory to get a permit for the construction or enlargement of mosques. Moving away from Muslims, let’s talk about Romany Gypsies because I can tell you and your followers love them! You banned the construction of Romany traveler camps, even when these sites were not illegal, which means you discriminated against a group based on their ethnicity. You also instated Respingimenti, or the ‘rejection’ of boatloads of mainly African immigrants, which in February 2012 was ruled a violation of Article 3 of the European Convention of Human Rights. Yikes…

Now let’s break down some of your policies and rhetoric for anti-immigration. According to a Pew Research study, ¾ of the Northern League members say immigrants are a burden to the Italian economy because they “take” Italians’ jobs (Pew Research, 2018). Quite honestly, I’ve had a lot of practice with this argument over if immigrants “take jobs” or not since I lived through four years of the Trump administration. Simply put, thanks to a study conducted by Egidio Riva and Laura Zanfrini, the jobs immigrants get are the jobs natural-born citizens do not want to do. That is, the farming, the manufacturing, the cleaning, the hospitality sector (which you should be grateful for since tourism is the only thing keeping your economy running, might I add), and the long-term care. Or in other words, the low-skilled jobs of Italy (Riva, Zanfrini, 2013, 2). On top of that, your aging population, since so many of the young adults of Italy want out of your populist country, have contributed to the labor shortage, so you should be thankful these immigrants are willing to work in your country to keep your horrific, broken economy afloat. Immigrants entering Italy are taking jobs that none of the natural-born citizens want, therefore they are not stealing “your jobs,” they are taking the jobs that are always hiring.

Next from the Pew Research study, about 7-in-10 League supporters believe that immigrants increase the risk of terrorist attacks in Italy, including 59% who strongly believe immigrants increase the risk of such attacks (Pew Research, 2018). With over half of the Northern League supporters believing that immigrants increase terrorist attacks, this causes serious safety concerns for immigrants in Italy. If you did look at the breakdown of who was entering your country as Michelle Groppi did, you would find that majority of “Muslims in Italy are first-generation, male immigrants from North Africa who have come to Italy to seek work.” (Groppi, 2017, para. 4). Most Muslims coming to Italy are here with the intention to work, not because they are planning a terrorist attack. Moreover, according to a survey done by the author, “81% of surveyed Italian Muslims claimed to love Italy and its culture,” (Groppi, 2017, para. 5). With such a high number of Muslim individuals happy with living in Italy and the Italian way of life, there is no reason to raise concern and instill fear for safety in the Italian population, like Salvini and the Northern League do.

But let’s not also forget, before you blame immigrants for terrorism, the history of homegrown terrorists in Italy. First, there are the Red Brigades. The Center for International Security and Cooperation at Stanford University says the Red Brigades are “a far-left extremist group of communist militants of the late 1970s and 1980s,” (Center for International Security and Cooperation). This group carried out violent attacks on right-wing politicians, factories, law enforcement, and other symbols of capitalism and state repression. Next, there’s the New Order and Black Order, who, according to Kenneth Langford, are far-right terrorists in Italy (Langford, 1985). The New Order and Black Order had carried out wide-scale bombings targeting train stations, government buildings, banks, and anti-fascist rallies. Third, and certainly, the most frightened group of individuals for homegrown terrorism in Italy, is a political party. The Counter-Extremism Project found that Forza Nuova is a far-right political party that is described to be ultra-nationalist, conservative, and neo-fascist (Counter-Extremism Project, paragraphs 14-20). This political party, which is allowed to run in elections, capitalizes on the issues of a weakened economy and the arrival of refugees from the Middle East by committing high-profile acts of violence. So, Italians know, the government even knows, this political party commits acts of violence on immigrants yet still allows the party to run for offices. Homegrown terrorists seem to be more of a threat than terrorists from the Middle East or other countries. These homegrown terrorists, your own Italians that you are trying to protect, are the more violent and have higher acts committed in your country, yet you are more concerned about being openly racist to Middle Eastern over this situation.

The arguments Matteo Salvini and the Northern League are using to spread their anti-immigration rampage do not hold up well against a counterargument. To claim that immigrants are stealing jobs from Italians is plain wrong and is propaganda and misinformation. The jobs these immigrants take are low-skilled, low-paying jobs, which Italians don’t want. Natural-born Italian citizens are a bigger threat in the aspect of terrorism than immigrants, Muslims. Italy allows a political party, who are labeled as’ terrorists,’ to run in elections and are given a platform to project their ideologies on. None of Italy’s issues are at the immigrants’ fault. On the contrary, the Italian government and the Italians’ failure to manage their economy correctly are what cause these economic, social, and political problems. This spread of misinformation is dangerous for everyone in Italy. This rhetoric causes large spikes in violence against immigrants. This also is dangerous for natural-born citizens, as they are not getting reliable, truthful information from the people who they should be able to trust, their government. So, Matteo, I think you need to find a different focus in your political party and for when you campaign because the anti-immigration stance is getting old. And, I now understand why my great-grandparents left Italy, it was because of politicians like you.

Best,

Kayla DeMarino

0 notes

Text

Italy's Political Landscape

Source: Reuters

Italy is the only Western European Democracy to see such a high level of support for populist actors. After the complete crumble of what Italians call “The First Republic,” there was a 40% jump in votes for populist political parties in the Italian general election in 2018. The First Republic was the period from 1948 to 1994 when Italy began creating its own democracy. To understand the political landscape of Italy, it’s crucial to look at Italy’s modern political history, the main populist actors, movements, and parties, and how they challenge rights-based democracy.

Up until 1919, Italy was ruled by a constitutional monarch or an authoritarian ruler. In 1919, Italians were introduced to an electoral system. This system allows citizens of Italy to vote for which political parties get placed in parliament. The creation of the electoral system allowed Italy to closer reach a parliamentary republic.

Between 1945 and 1994, two major political parties dominated: the Christian Democracy and the Italian Social Movement. From 1983 to 1991, a coalition was formed with the Socialists, Republicans, Democratic Socialists, and the Liberals. A coalition is essentially a parliament of advisors, each from different political parties. In 1994, Silvio Berlusconi became prime minister. In 2013, there was the Democratic Party, the Left Ecology of Freedom, the People of Freedom, the Northern League, the Five Star Movement, and the Civic Choice. Finally, in the 2018 elections, there were only three remaining political parties: the Northern League, Forza Italia, and the Five Star Movement. The current government Italy has is a parliamentary republic. Italy’s coalition government allows for many different political groups to have a chance at representation in the Italian parliament, causing quick turnover in political parties represented in the parliament.

In Western Europe, Italy has the largest amount of populist actors and ideologies. Four active political parties are populist or have populist tendencies. The parties are the Five Star Movement, the Northern League, Forza Italia, and the Brothers of Italy.

The Northern League is one of the most prominent populist parties in Italy currently. It is a right-wing populist group led by Matteo Salvini. Their stance on immigration, as well as their feelings towards political and institutional elites, is what coins them as populists. Another prominent populist party in Italy is Forza Italia, led by Silvio Berlusconi. This party’s negative feelings towards political and bureaucratic elites, and the elites’ stances on immigration, are why they are considered populist as well. Both these groups believe that immigration must be halted because it affects the “true Italians’” way of life and culture, or, in populist terms, “the people’s” way of life.

When talking about how populism can challenge rights-based democracy, we can look at the Northern League’s reign in 2008. Berlusconi, the prime minister at the time, limited how Muslims could practice their religion. Berlusconi made it mandatory for Muslims to celebrate their religious activities in Italian, but no other religion had to abide by this rule. He also targeted Romany Gypsies by banning the construction of traveler camps, which is an example of discrimination based on someone’s ethnicity/culture. Berlusconi also went as far as trying to limit freedom of the press and freedom of speech. He would influence what should be shown on mediums, such as TV and radio, to make sure it painted a positive picture of his party and himself. If a journalist didn’t listen, he would pressure the superior of the journalist to fire them and would often sue these journalists. Overall, populism can affect rights-based democracy through the suppression of basic freedoms every individual in Italy has, as written in the Italian Constitution.

Populism in Italy has to do with the political landscape, the political instability, and the sheer number of populist leaders in the political parties of Italy.

0 notes

Text

Anti-Immigration Rhetoric in Italy

Photo Credit: Sylvia Poggioli, NPR

Anti-immigration sentiments have been on the rise for the past ten years in Italy. Mostly to blame are the populist political groups who spread this hateful anti-immigrant rhetoric. Parties such as the League, Brothers of Italy, and the 5 Star Movement have, in the past decade, focused their attention on these “criminal” immigrants coming to ruin Italy for true Italians. The media also plays a valuable role in the spread of anti-immigrant information, as well.

Anti-immigration rhetoric causes rifts in Italian society. Many Italians believe that these immigrants are “stealing” true Italian jobs. Unemployed Italians are even more likely to believe these anti-immigration sentiments. The unemployed blame immigrants and the European Union policies for their situation, they also blame center-left parties for failing them. COVID-19 has also helped heighten anti-immigration agendas. Matteo Salvini, Giorgia Meloni, and other populist actors in Italy have used the pandemic to call for tightened borders and blame immigrants and tourists for bringing the virus into Italy. Salvini wants to go as far as closing all of Italy’s borders, especially because of the continued fighting in Syria, which has created 1 million refugees- with all of them heading to Europe. The panic created by populist actors and the media have created a serious rift in Italian society, with Italians worried that all immigrants are dangerous and sickly.

Ever since Matteo Salvini stepped in as leader of the Northern League in 2013, there has been a severe uptick in anti-immigration sentiments amongst the Italian population. 35% of Italians in 2018 named immigration as one of the two most important issues facing their country, which is up 18% from 2014. Pew Research goes as far as to say 51% of Italians see immigrants as a burden to this country. Matteo Salvini, during his 14-month stint as deputy prime minister from 2018-2019, wanted to create a division between true Italians and the ‘outsiders.’ He achieved that goal once he placed his decrees in place. Salvini describes that the true Italian is a heterosexual, Catholic household where the father works, and the mother takes on a domestic role. This kind of rhetoric affects any immigrants or tourists in Italy. Salvini describing all migrants as ‘criminals’ creates this ideology that, even if the migrant is legally allowed to be in the country, they will still face discrimination, a hard time assimilating, and often, violence.

Opposing politicians have accused Salvini, Meloni, and other right-wing populist leaders of creating propaganda around anti-immigration policies that have clearly contributed to creating a climate of hostility and legitimizing racist violence. For example, a young male migrant was attacked by a group of Italian teenagers after he refused to give them a cigarette. It was justified by the Italian population because he was a ‘criminal’ immigrant who was “probably” illegal anyways. The type of rhetoric politicians uses while speaking on critical societal issues can affect how the majority views the societal problem. By creating this idea that all immigrants are ‘criminals’ and ‘dangerous,’ native Italians will start to view them as such.

Media plays a crucial part in fueling this anti-immigrant fire. Berthin Nzonza, president of Turin-based NGO Mosaico Refugees- an organization run by and for refugees arriving in Italy- makes a valid point. He claims that ever since the populist party, the Five Star Movement, first entered the Italian Parliament, the media has portrayed refugees as the “cause of evil,” covering them with accusations of infecting the nation and stealing jobs. Then, when Italy was hit with COVID-19, the media claimed-at first- those migrants were “immune” to the virus. That quickly changed to migrants being “carriers” of COVID. This kind of media coverage helps to paint immigrants as dangerous, spreading fear throughout the peninsula. This kind of marginalization reflects a long history of propaganda against refugees in Italian media.

One of the top right-wing media outlets in Italy, Il Gionarnale, is owned by the Berlusconi family since 1977. Silvio Berlusconi is the ex-prime minister of Italy and was the leader of Forza Italia, a right-wing populist group. Having such a prominent figure in Italian media become the prime minister is sure to cause the media to portray Berlusconi’s anti-immigration views in a positive light especially when it’s his own media brand reporting the story.

National media outlets in Italy, also, create these “symbolic internal borders,” by portraying a negative image of refugees that is specifically linked to security issues for the country, developing asylum seekers as a social problem that must be fixed.

Media plays a huge factor in the spread of anti-immigrant rhetoric. Since one of the most prominent media owners was prime minister, it would be difficult, and most likely, career-ending if a journalist or media outlet published a story supporting immigration and asylum seekers, as the government and Berlusconi would slap the journalist or media outlet with a civil lawsuit, causing the individual or the company to pay millions in reparations and legal fees.

Populist actors, also, have a huge effect on anti-immigration rhetoric. For example, the Northern League’s stance on immigration is what coined them as populists. They believe that immigrants are hurting Italy and true Italians, as they are taking away their jobs and are dirty criminals. In 2010, only 1 in 5 Italians see immigration from the Middle East, Africa, and Eastern Europe as a good thing, or 20%. Populist actors, such as Salvini, try to create a rift in Italian society to get their anti-immigration ways heard. They instill fear in native Italians about immigrants so they can profit off the fear and cut off borders. By doing so, they would lose many economic and social benefits, such as GDP, taxes, and probably the most important, tourism. Why would anyone want to go to a country where there is no cultural diversity?

Overall, anti-immigration policies and rhetoric are extremely prevalent in Italian society. This kind of rhetoric only hurts Italy. With many of the younger population of Italy moving out of Italy, they should be happy that refugees want to come and live in Italy. The media acts as a gatekeeper in Italian media, they decide what they want people to know, and what they don’t want people to know. This is dangerous, as censoring your own people will not help grow the country, as Italy so desperately needs after their recession and the pandemic. Populist leaders try to draw a rift in society, create the true Italians vs. immigrants/refugees, which promotes more violence in the country and helps populist actors gain the one thing they really want. Power.

0 notes

Text

Italian Media Landscape

Italy’s media landscape is ranked 46th in the World in Reporters’ Without Borders’ 2018 World Press Freedom Index. There is a great deal of control that the Italian government has over the Italian media and very little separation of state and media. There is also very little press freedom and many challenges for journalists to overcome. Part of the challenges and the little press freedom in Italy is due to the populist actors, who play major roles in the Italian government, even becoming prime ministers.

Italy is a “TV-centered” country, according to Shehata and Stromback’s Political Communication article. This means citizens would rather consume news and media on a television screen than through physical newspapers, or even the Internet. In fact, the number of Italian citizens that use the Internet is lower than any other country and their digital infrastructure is less developed.

Politics and journalism go hand-and-hand in Italy. There have been many instances where journalists enter the political field and politicians become journalists. An example of this is Silvio Berlusconi, who was a media tycoon turned prime minister. He was also a major populist actor for Italy. With politics playing a huge role in journalism and news reporting, there is no autonomy in the media. Italian media is easily influenced and supports whoever is in power due to the punishment the journalists would receive if they wrote something portraying the current government negatively. The state also plays the role of owner, regulator, and funder to the media. An example of this is the Italian Public Service Broadcasting- it is owned by the Treasury Ministry. There is little separation of politics in the Italian media.

Being a journalist, or working for any type of Italian media outlet, is a dangerous job. Due to the large mafia presence in Italy, and their close ties to the government, they are one of the biggest threats to free media in Italy. There are nearly 200 journalists who receive around-the-clock police protection because of threats and violence from the mafia. The main political parties of Italy tend to have a strong influence over the media. Journalists opt to censor themselves due to pressure from politicians. This violates press freedom, even though the government isn’t directly telling journalists to not post a certain article, the journalists know the repercussions if they were to post something controversial. This also infringes on the journalistic moral and ethical codes, that journalists should have the right to post what they want, to keep their people in the know.

There are many challenges that Italian media face when it comes to the lack of press freedom and the grip the government has over the media. Populist groups like the Five Star Movement and the Lega have begun to use social media to speak to their followers, and to discredit journalism on these platforms, using the Trump’s administration “fake news” as the excuse. Because of this, journalists were cut out of the information cycle and lost their watchdog role.

Another challenge journalists and media outlets face is that Italian newspapers receive government funding, yet in the past decade, direct and indirect support for news organizations has fallen. In 2007, the news organizations would receive 170 million euros, in 2017, it fell to 62 million euros. These cuts will threaten the existence of many news outlets, especially small, locally operated news outlets. The IPI also stated that also a 2019 budget law was put into effect, which is supposed to gradually reduce public money for media outlets over the next three years. There will be no money left by 2022.

Finally, the last increasingly hard challenge journalists and the media face are libel laws. One of the greatest difficulties faced by journalists in Italy is the frivolous slander lawsuits. These lawsuits force journalists to spend a great deal of money, time, and energy into defending themselves, while also running the risk of having to pay damages because of a potential mistake that was in good faith. Defamation is a criminal offense in Italy, which allows journalists to face up to 6 years in jail. There are also civil suits that lead to self-censorship because journalists want to avoid these lawsuits issued by the government. This results in the loss of information and diversity of reporting for audiences. According to Stefano Corradino, director of the Italian Press Freedom Organization, says these lawsuits are, “a form of preventative intimidation in respect to journalists. They ask for millions in euros of compensation not to make money, but to discourage journalists from doing their jobs.”

There are many challenges journalists and media outlets face, whether it be political, economically or legal repercussions, which diminishes the quality of the news for citizens.

The relationship that the Italian media has with populist actors has major turmoil. One example of this relationship is when Silvio Berlusconi was prime minister. Berlusconi is a media tycoon turned prime minister. He was prime minister four different times (1994-1995, 2001-2006, and 2008-2011). Berlusconi is a member of Forza Italia, a major populist group in Italy. Berlusconi used populism to create this illusion that journalists and the media were “the elite,” trying to project these fake narratives to make himself and his party look bad, and then made “the people,” the hardworking, native Italians whom the media was trying to brainwash. Berlusconi often used defamation lawsuits on journalists or anyone that opposed his government, and often got fired and had to pay the government money. He was also known for indirect censorship, where he would suppress or hide information, like his sex scandal in 2008. The relationship between the media and the populist actors of Italy is seen clearly through the example of Berlusconi. He used “the people” to create this depiction of the media as the “Bad guys,” or “the elites.”

The media landscape of Italy is very different from the United States and other 1st world countries. Italian populist politicians have a lot of power in the Italian media. They slap them with libel lawsuits, they speak ill of some of the top journalists in Italy, which often leads to losing their jobs, and take away quality journalism and reporting just because something doesn’t portray the government in the right light. Populism plays a huge role in these issues, as many populist leaders paint the media as the “bad person,” “the elites.” They create this idea that the media is evil and doesn’t want what is best for their country. But they just want to be able to do their job without any repercussions.

0 notes

Text

Special Issue Brief

Dan Henson, Piazza Venezia, Credit: Getty Images/iStock

For nearly ten years, Italy’s economy has been stagnated. The economy has not expanded, but the debt keeps racking up. Then, in 2018, the official start to a recession occurred. Since then, COVID-19 made it nearly impossible to recover, but with a new prime minister- an old banker- many Italians feel that he will help them out of this hole that’s been dug for ten years.

Italy is now in the longest recession they’ve seen in twenty years. The economy has been contracted for the last six consecutive quarters and for nearly a decade, has remained stagnated. Unemployment is at more than 11% and is 36% for Italians under 25. The government had ceased operations of 2.2 million companies due to the COVID-19 lockdown. This left 7.4 million employees without a job. This matters because it directly affects everyday and average hard-working Italians. Many Italians have lost their jobs during COVID-19, with unemployment being well above 11%. This is due in part to the massive amount of beatings the tourism sector of the economy took, leaving businesses unable to keep their accommodations open and pay their employees, therefore they had to be let go. Since many people lost their jobs, they’re going to unemployment payments for support, but Italy has already been in debt prior to COVID, so they don’t have the money to pay these unemployed individuals. So, they then ask for loans from the EU or other countries, further putting them into debt. This economic system is not sustainable and will cause the third-largest economy in Europe to collapse, leaving the people helpless.

This economic crisis affects many groups of people in Italian society. All self-employed people and people on a temporary contract are facing the brunt of this. All employment sectors, besides construction, are weak, especially, those in the services sector. Each government official who has failed to pull Italy out of debt also sees this affect their rankings in the polls for the next election. Mario Draghi, who was recently re-elected, is the only Italian prime minister to actively put policies in place that haven’t backfired on the economy.

Though, with many people affected by this crisis, there are some individuals who believe this crisis cannot be the cause of the current political leader. Adriano Cozzolini, an Italian journalist, writes on a blog that the recession has nothing to do with the current government, but everyone should blame the systemic failures of the political-economic model that has been built for the last four decades. “Many of Italy’s economic problems were long-standing, including a high number of problem loans on its central banks’ balance sheets, combined with decades of slow growth.” There were many individuals who opposed whom to blame for this issue.

The media in Italy was closely monitored by the government when the news broke that Italy was in a recession. The government didn’t want any misleading or false information to get spread around- not that it would because nearly half of Italians don’t trust the media. If the government found out about misinformation, they were subjecting the journalist to public humiliation, calling them out for spreading lies and “fake news.” This urged the company to come forward and fire any journalist who misspoke, to save the media company’s reputation. This is a typical populist government at work, against the media and willing to control them any way they can.

The populist actors during this economic crisis have redirected the blame from themselves to the European Union, less extreme Italian politicians, and Italy’s economic-political model. They claim that they, “the people”, did everything in their power to keep this from happening, but since other political figures refused to withdraw from the EU and start their own currency, this is the aftermath of that. The “elites” were the EU, the less extreme politicians, and the economic-political model that has been built for the past 4 decades.

The biggest social issue that is concerning the Italian people today is the state of their economy. A five-year-long recession, failure to grow, a pandemic, and populist leaders all contributed to the current state of Italy’s economy.

0 notes