Video

youtube

The Infinited Fiber Company has built a technology that recovers the cellulose from cotton and transforms it into new, cotton-like textile fibres with added-value properties like improved colour uptake and antibacterial properties.

Our patented technology takes piles of trashed textiles that would otherwise be landfilled or burned and transforms them into brand-new premium-quality fibers for the textile industry. While we currently focus on using cotton-rich textiles, the beauty of our technology is that it can also turn other cellulose-rich materials – old newspapers, used cardboard, crop residues like rice or wheat straw – into the same fantastic fiber.

We break waste down and capture its value at the polymer level, giving it new life as Infinna™ – the unique textile fiber that looks and feels like cotton and is known scientifically as cellulose carbamate fiber.

Our technology is ready, proven and available for licensing. We’re also boosting our own capacity and preparing to build a commercial scale factory in Finland. We’re excited to be working with like-minded partners to make textile circularity an everyday reality.

https://infinitedfiber.com/our-technology/

0 notes

Video

youtube

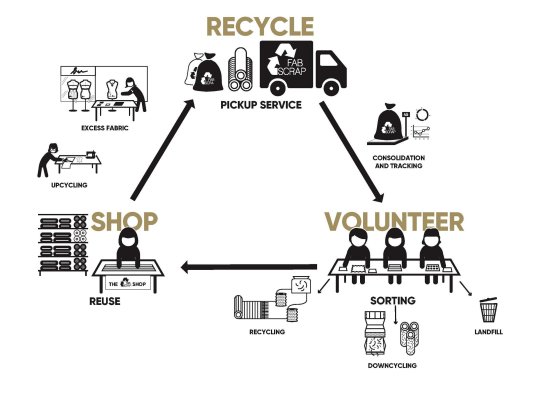

Jessica Schreiber founded FABSCRAP in 2016 to take on the fashion industry’s textile waste problem. Jessica was inspired to start FABSCRAP after working at New York’s Department of Sanitation. To date the nonprofit has partnered with more than 500 fashion brands to rescue more than 500,000 pounds of fabrics from going to landfills. FABSCRAP gives designers and brands a place to recycle fabric scraps, cuttings, headers, mock-ups, samples, overstock bolts, production remnants, and any other unwanted excess fabric that might come about during the creation and manufacturing process.

https://fabscrap.org

0 notes

Text

Waste flows Myra J. Hird

Paul Crutzen’s term ‘Anthropocene’ marks an unofficial yet widely accepted geological time scale designating the point at which human activity has intersected, in its significance and magnitude, with planetary geological forces. Crutzen initially located the beginning some two hundred years ago, but now places “the real start of the Anthropocene” on a specific date: July 16, 1945 – with the Trinity detonation and its fallout, radioactive waste. Whether nuclear fallout or carbon dioxide, waste has become the signifier of the Anthropocene, inaugurating the only epoch that centralizes humans.

Mary Douglas’s (1966) influential theorization of waste as “matter out of place” initiated a generation of studies focused on the complex ways in which purification practices – defining certain things and people as waste to be excised – form and stabilize communities. Industrialism, capitalist economies, and neoliberal governance mean that this expurgation is now global in scale and topography (Spaargaren, Mol and Buttel 2006; Dauvergne 2008). One characteristic contemporary waste is its proclivity to move, to transform, to flow (Gille 2010). Critically examining how and why waste flows politically, economically, culturally, symbolically, socially, and materially offers important insights into our past, present, and possible future relationship with waste, the environment, and our species.

These analyses share an appreciation for waste flows as complex networks of socio-cultural and bio-geological processes. For instance, neoliberal governance seeks to manage waste as a techno-scientific concern that leaves circuits of mass production and over-consumption undisturbed (Gregson and Crang 2010). Managing waste suggests it is definable (things count or do not count as waste); relatively stable; and amenable to ‘fixing’ practices (such as landfilling, recycling, dumping, and incineration) that isolate, immobilize, and control waste.

However, waste flows are always contingent, uncertain and temporal. Not only does waste at times exceed its mundane cultural, economic, and symbolic governance (Hird et. al. in press), but waste may physically leak, spill, seep, corrode, slip, collapse or explode, contaminating groundwater, soil, the atmosphere, and organisms (Hird 2013; Gabrys 2009). “Trash may dissemble the truth of its being by presenting itself as [an] immaterial, innocuous substance divorced from the relations to physicality” (Kennedy 2007: 162) but in actuality, bio-geological processes are always already actively involved (Clark and Hird 2014; Hird 2012, 2013). The millions of people who live in and on dumpsites and survive by directly handling waste, or who live downstream from waste’s fallout are acutely aware of waste’s proclivity to materially flow (McGovern 1995; Lepawsky and Mather 2011). According to Ulrich Beck, this is what it means to live in a “risk society” in which complex technological innovations created as solutions “contain the seeds of new, more difficult problems” (2009: 113). Or as Brian Wynne reminds us of waste repositories such as landfills, these are sites where “…natural processes and human interactions are jumbled together in complex and widely variable ways, making a badly structured and, indeed, indeterminate behavioural-technical risk-generating system” (1987: 1).

The Anthropocene marks an epoch of permanently temporary waste deposits left for imagined futures to resolve. Experts estimate landfill longevity in terms less than two hundred years. Incineration fly ash is often landfilled, adding concentrated toxic heavy metals to leachate and clogging landfill pipes; thereby undermining attempts to control leachate flow. Freezing mining waste “in perpetuity” signifies an epoch in which the responsibility for waste is abdicated to future generations. This projection, however, already manifests in the present: global warming is melting the permafrost supposed to keep mining waste frozen in Canada’s north, and bacterial exuberance transforms landfill waste into new entities scientists cannot anticipate (Hird 2012, 2013).

We are not so much leaving behind our waste for some imagined future humanity to decipher our history, as we are bequeathing a particular futurity through a projected responsibility for the toxicity, contamination, and resource depletion our epoch created. Waste, therefore, introduces a paradox: the Anthropocene marks humans’ significant re-assemblage of the planet at the same time that it puts an end to any lingering sense to human exceptionalism.

https://discardstudies.com/discard-studies-compendium/#Wasteflows

0 notes

Photo

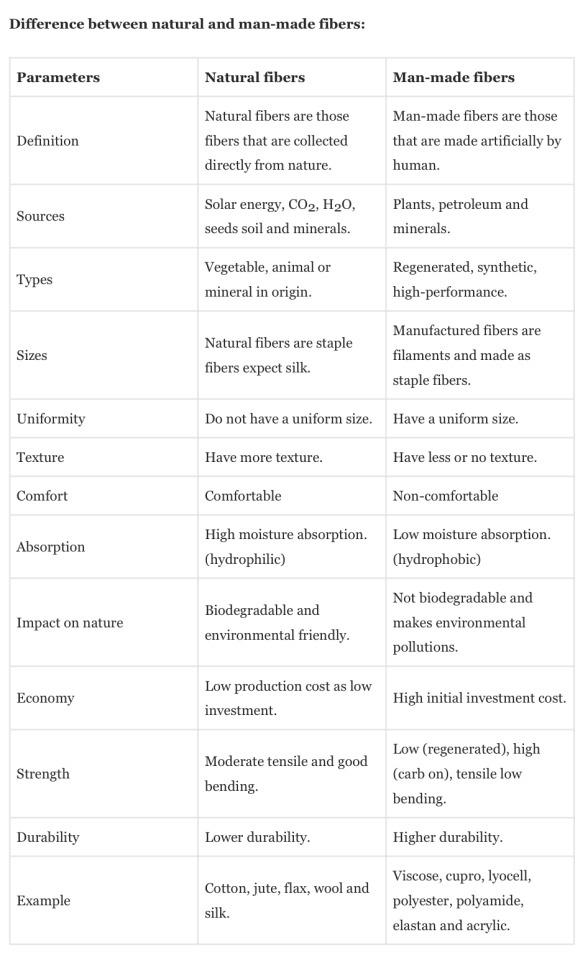

Worn Again Technologies’ has created a technology that can separate and recapture polyester and cotton from blended materials. So if you have a blended cotton-polyester garment, the cellulose from the cotton and the polyester can be extracted and recovered back into raw materials that are close, quality-wise, to virgin materials.

https://wornagain.co.uk

0 notes

Photo

The Rememberme project by German designer Tobias Juretzek involves a process of dipping around 13lbs worth of discarded clothes into resin and compressing them into a mould. The result is a sturdy chair with smooth edges in a myriad of colour options. The collection, which also includes a Rememberme table, is inspired by the memories associated with clothing and preserving things we wear during significant life events.

“Rememberme Chair wants to achieve more than pure functionality. Instead of being a dumb servant, it tells an individual story. Every chair is unique through its material and gets its own expression. The characteristics of the clothes thereby convert to a language. Clothes carry numerous adventures and stories. The chair transports these to a new expression. This illustrative exposition invites the spectator to exciting stories.”

Tobias Juretzek

http://studionito.com/studio_nito_rememberme_chair.html

0 notes

Video

youtube

Transforming used textiles into eco-friendly bricks. This is FabBRICK's approach to preventing waste.

Clarisse Merlet the architect behind this project.

https://www.fab-brick.com/fabbrick-english

0 notes

Photo

The Waste Action Plan for a Circular Economy Action Plan (2020-2025)

Traditionally, waste policy has tended to focus on how we treat the waste we produce and how to achieve the right balance between waste recycling, recovery and disposal

Waste policy can no longer be about the narrow consideration of how to treat the waste we produce, implicitly based on a linear or take-make waste consumption model that cannot be sustained how we consume materials and resources, how we design the products that households and businesses use, how we prevent waste generation and resource consumption and how we extend the productive life of all goods and products in our society and economy.

According to the circularity gap report 2020, material consumption has trebled from 26.7 billion tonnes in 1970 to 92 billion tonnes in 2017. Half of total greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and more than 90% of biodiversity loss and water stress come from resource extraction and processing

By 2050, we will need three planet earths to meet our resource demands in a business as usual scenario. Meeting climate targets requires a transformation in the way we produce and use goods transition away from fossil fuels towards renewables and supplemented by energy efficiency measures can only address 55% of emissions.

45% comes from making things. Therefore, making less ‘stuff’ or making ‘stuff’ with fewer resources - the essence of the circular economy

It identifies 7 key product value chains: electronics and ICT; batteries and vehicles; packaging; plastics; textiles; construction and buildings; and food, water and nutrients

The overarching objectives of this action plan are to:

• shift the focus away from waste disposal and treatment to ensure that materials and products remain in productive use for longer thereby preventing waste and supporting reuse through a policy framework that discourages the wasting of resources and rewards circularity;

• make producers who manufacture and sell disposable goods for profit environmentally accountable for the products they place on the market;

• ensure that measures support sustainable economic models (for example by supporting the use of recycled over virgin materials);

• harness the reach and influence of all sectors including the voluntary sector, R&D, producers / manufacturers, regulatory bodies, civic society; and

• support clear and robust institutional arrangements for the waste sector, including through a strengthened role for Local Authorities (LAs).

The EU has the ambition of achieving climate neutrality by 2050, decoupling economic growth from resource use while maintaining long term competitiveness and leaving no one behind the European Commission proposes that the EU needs to accelerate the transition towards a regenerative growth model that gives back to the planet more than it takes, advances towards keeping resource consumption within planetary boundaries and strives to reduce its consumption footprint and double its circular material use rate in the coming decade.

Textiles

The measures set out below will focus on our current understanding of the textile waste stream within the State as well as principles for future direction of textile management.

We will:

• Develop separate collection framework proposals that take account of the potential global impacts of the international trade in used textiles and in consultation with existing collection operators.

• Review regulation of textile collection banks to ensure compatibility with SDGs.

• Support improved data on the nature and extent of the used textile stream.

• Ban textiles from the general waste bin, landfill and incineration.

• Promote eco-design for clothing and textiles in collaboration with Irish fashion designers and retailers.

• Support an education and awareness campaign around textiles as a theme of SDG 12 Sustainable Production and Consumption.

• In 2021, establish a short-term textile industry action group that identifies opportunities to:

• capitalise on the value (jobs, economic and resource value) of textiles present in Ireland, including reuse and preparation for reuse and also recycling; and

• explore options to improve future circularity in textiles including the potential for introducing Extended Producer Responsibility schemes for textiles.

• Over the medium to long-term, examine the potential role of economic instruments (e.g. levies) on ‘fast fashion’ which could also support higher value indigenous producers by reducing the cost differential.

0 notes

Photo

EPA STUDY REPORT: Nature and Extent of Post-Consumer Textiles in Ireland (2021)

This study was commissioned by the Environmental Protection Agency to determine the nature and extent of the current consumption of new textiles and generation of post-consumer textiles in Ireland and reviews the current systems used to collect textiles for reuse, recycling and disposal.

According to the European Environment Agency in 2019, the supply chain pressures from textiles is the fourth highest for use of primary raw materials and water, after food, housing and transport, and the fifth highest for greenhouse gas emissions. Measures for textiles explicitly feature in the revised Waste Framework Directive – notably requiring Member States to set up separate collection for textiles by 2025, to encourage the re-use of products and the establishment of systems promoting repair and re-use activities.

The report makes recommendations to improve separate collection of post-consumer textiles, to facilitate and encourage more reuse within Ireland, to foster more repair of textiles, and to take longer-term steps towards more sustainable consumption and use of textiles.

The study identifies the following initial recommendations to set Ireland on the path towards a circular textiles framework:

There is a pressing need to obtain better data on the flows and fate of post-consumer textiles. For both textiles that are ‘waste’ and textiles that are not waste, as Ireland moves towards the circular economy model, it is important that the flows of all post-consumer textiles are understood.

Waste prevention and sustainable consumption must be introduced in this sector. This could include measures such as green procurement; reducing fashion-driven personal consumption; increasing reuse; facilitating repair; and at end of life, favouring reuse/recycling over disposal.

Targeted educational campaigns are required to raise awareness for the public on sustainability issues as raised in this report.

Separate collection of textiles in Ireland needs to be significantly improved, particularly at the domestic level which is the major source (around 67,000 tonnes per year of clothing, other textiles and textile packaging in the municipal waste stream). This should be underpinned by better information for the public on textile recycling.

In conjunction with improved collection methods, there is also a need to locally develop capacity and outlets to manage post-consumer textiles. For example, there is a need to explore strategies to maximise sales via existing outlets, as well as upcycling, downcycling and recycling opportunities.

Increased reuse within Ireland will benefit Ireland’s skill profile, create opportunities for training and employment, and in the longer-term foster innovation in circular economy design.

Additional regulation of textile banks should be considered – potentially through a code of conduct operated by the charities regulator.

International best practice examples are useful and provide guidance, however, local pilot-projects are required to understand how novel measures might be suited to the Irish context.

Going forward, the findings and recommendations from this study will inform future consultations and measures identified in Ireland’s Waste Action Plan for a Circular Economy to support the requirement for separate collection of textiles by 2025 and to improve circularity in textiles in Ireland.

https://www.epa.ie/publications/circular-economy/resources/nature-and-extent-of-post-consumer-textiles-in-ireland.php

0 notes

Photo

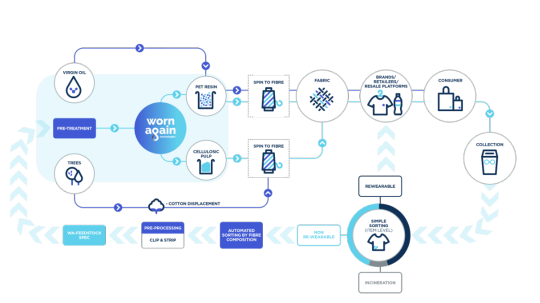

EU strategy for sustainable and circular textiles 2021

The EU strategy for sustainable and circular textiles addresses the production and consumption of textiles, whilst recognising the importance of the textiles sector. It implements the commitments of the European Green Deal, the new circular economy action plan and the industrial strategy.

Textiles are the fabric of everyday life - in clothes and furniture, medical and protective equipment, buildings and vehicles. However, urgent action is needed as their impact on the environment continues to grow. EU consumption of textiles has, on average, the fourth highest impact on the environment and climate change, after food, housing and mobility. It is also the third highest area of consumption for water and land use, and fifth highest for the use of primary raw materials and greenhouse gas emissions.

By looking at the entire lifecycle of textile products and proposing actions to change how we produce and consume textiles, the Strategy presents a new approach, addressing these issues in a harmonised manner.

Objectives

The strategy aims to create a greener, more competitive sector that is more resistant to global shocks. The Commission's 2030 Vision for Textiles is that

all textile products placed on the EU market are durable, repairable and recyclable, to a great extent made of recycled fibres, free of hazardous substances, produced in respect of social rights and the environment

”fast fashion is out of fashion” and consumers benefit longer from high quality affordable textiles

profitable re-use and repair services widely available

the textiles sector is competitive, resilient and innovative with producers taking responsibility for their products along the value chain with sufficient capacities for recycling and minimal incineration and landfilling

Actions

The Strategy lays out a forward-looking set of actions. The Commission will

set design requirements for textiles to make them last longer, easier to repair and recycle

introduce clearer information on textiles and a digital product passport

empower consumers and tackle greenwashing by ensuring the accuracy of companies’ green claims

stop overproduction and overconsumption, and discourage the destruction of unsold or returned textiles

harmonise EU Extender Producer Responsibility rules for textiles and economic incentives to make products more sustainable

address the unintentional release of microplastics from synthetic textiles

address the challenges from the export of textile waste adopt an EU Toolbox against counterfeiting by 2023

publish a transition pathway by the end of 2022 - an action plan for actors in the textiles ecosystem to successfully achieve the green and digital transitions and increase its resilience

0 notes

Video

youtube

Scientist Veena Sahajwalla experiments with new recycling processes and ideas about how to save waste from landfill. Inspired walking the streets of her Mumbai neighbourhood as a child, Veena observed almost everything was reused and "nothing was wasted". This can-do attitude shaped her engineering career and sowed the seeds for some ground-breaking ideas, including making steel from car tyres. Now she's unveiling her latest invention, a "micro factory" that creates building materials and tiles from waste textiles and glass. It’s a revolutionary concept. But will it work outside the lab?

0 notes

Photo

The rise of polyester as a material used in the textile industry has been key driver in the surge in fast fashion retail industry since the 1990′s. Globally, polyester is the most dominant man-made synthetic fibre, with a share of around 77% in total production and consumption of man-made fibres.

Systems for textile-to-textile recycling are in development but most recycled polyester is currently still made from plastic bottles.

The PET used in fabrics by the fashion industry was invented in 1941 by John Whinfield and James Dickson, two chemists in the UK who developed PET in response to the invention of nylon a few years earlier. Chemical manufacturing giant DuPont purchased the rights to their invention, known as Terylene at the time, and eventually developed their own version, Dacron, in the early 1950s. This endorsement by DuPont, along with the fact that the key ingredient petroleum was readily accessible in the middle of the 20th century, opened up the use of PET to the fashion industry and started the trend of using polyester in clothing.

1 note

·

View note

Video

youtube

Global Fibre production in 2020 | Textiles Exchange Report

68.2% Synthetic Fibers (Polyester 52%)

32.7% Plant Fibres

6.5% Manmade Cellulosic Fibres

1.7% Animal Fibres

The global fibre production has almost doubled in the last 20 years from 58 MT in 2000 to 109 MT in 2020. Global fibre production likely to rise 34% by 2030.

0 notes

Video

youtube

Buying less and season-less clothing

Currently only 1% of textiles is recycled in to new clothing. The lack of technology to recycle materials is considered a factor as garments made from a mix of materials are harder to recycle than mono materials. While major fast fashion brands are developing new technologies to recycle their post-consumer textiles, many argue that a technological solution will never be enough to deal with the level of textile waste currently being produced globally.

The underlying problem comes back to levels of overproduction and overconsumption. Too much clothing is produced and bought regardless if it is eco-friendly or not. Buying clothes every four weeks is relatively new. Before the 90′s designers made clothes for two fashion seasons per year. Now fashion retailers put out clothing in as little as every two weeks, driving down prices and quality and increasing waste going to landfill and incineration.

0 notes

Photo

A close-up from Gr.gory Chatonsky and Dominique Sirois’s installation Telofossils, 2012. Courtesy of Xpo Gallery

0 notes

Photo

Media artist Gr.gory Chatonsky’s Telofossils (2013), a collaboration with sculptor Dominique Sirois and sound artist Christophe Charles, picks up on this context of technologies, obsolescence, and fossils. The exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Taipei, Taiwan, focuses on the slow, poetic level of decay that characterizes technopolitical society and nature. The “future archaeologist” perspective that Chatonsky summons with immersive affective moods created in the exhibition’s installations is akin to Manuel Delanda’s figure of the future robot historian that gazes back at our current world emphasizing not the human agency of innovators but the agency of the increasingly automated and intelligent machine (as part of the military constellation). The future archaeologist in Chatonsky’s installations and immersive narrative is a displacement of the human from a temporal perspective (the future) and from the Outside (alien species)...

Indeed, for Chatonsky, the double role of technology becomes understood through future as a fossil: in his words, “they participate to the exhaustion of our planet but they also constitute traces of our existences.”...

Hence the fossils of the future are the ones we live among, and in this speculative fiction, the extrapolation of current technopolitics is returned to us via memories of the future. This link of present and the forthcoming is implicitly there in any kind of an apocalyptic future scenario.The question is, why are we imagining now such postextinction futures, worlds that are mediated and in medias res—a mediated technological future?

The notion of the fossil is a hint at a future grounded in dysfunctional technology: indeed, similarly as in new insights in technology and repair studies, we need to be able to rethink the modernist fantasies (also visible in the historical maps of past imaginary futures in paleofuturism) of technology as clean, smooth, and progressing and replace such with the primacy of the accident.

Jussi Parikka,. A Geology of Media. University of Minnesota Press, 2015

0 notes