Photo

Week 10 (6/3-6/7)

In the midst of becoming extremely busy with watering in the increasing temperatures and weeding summer annuals that are trying to take over all of the cultivation sites, I participated in my first seed harvest this week. Our Plectritis brachystemon (Shortspur seablush) is indeterminately scattering seed now as it reaches the end of its life, and the weed cloth around it is covered with seed at various stages of maturity. This week I took a broom and swept between and underneath the vegetation to collect the seeds which have been dropped, and then spread them on a tarp in our farm’s barn so that they will have the chance to dry over the next couple weeks.

0 notes

Photo

Week 9 (5/27-5/31)

I was able to visit two more native plants growing operations this week. The first was the Center for Natural Lands Management South Sound Prairies Conservation Nursery in Olympia, Washington. This is the largest native plants farm I have seen yet- we were able to visit 4 separate cultivation sites where they had an extensive operation for growing native plants for seed and research. Like the Mt. Pisgah nursery in Albany, this operation prioritizes the minimization of their long-term environmental impact by using herbicides and pesticides as an absolute last resort and using mulch as opposed to weed cloth to reduce their plastic consumption. I appreciated their commitment to cultivating an agroecosystem as habitat. Their operation was very much research oriented, but they also produce a massive amount of seed each year.

The other site I visited was the Portland Metro Native Plant Center. This center’s purpose is to assist in restoration and preservation project within the Metro area’s land base, but they are not a seed producer. They have a couple acres of cultivated plants for research on growth needs and habits to inform restoration projects. My favorite part of this farm was observing their cultivation method for forest understory species. Functioning as a forest farm (within agroforestry definitions), they have planted beds of plants in the understory of a Douglas-fir stand. I found this extremely interesting! Although it does minimize their production capabilities, planting these understory species within this stand of trees creates the microclimate that would otherwise be created with the use of shade cloth. Since the purpose of the farm is largely to conduct research, I can see how this method can help the farmers to understand the plants they are working to preserve. It was very thought provoking for me to think about the potential to design a farm around the habitats certain plant species prefer.

0 notes

Photo

Week 8 (5/20-5/24)

This week I had the opportunity to step away from farm management activities for a bit to observe some other native plants growing operations in the area. The first stop was the Friends of Buford Park and Mt. Pisgah Native Plants Nursery in Albany, Oregon. This farm was unique in its small size, but high diversity of cultivated species. They had over 120 species in production for seed collection on just a few acres of land. Many of their plants were being grown in small plots or raised beds. They emphasized their desire to minimize their use of herbicide or pesticides, which is an issue that is up for debate amongst all native plants growers. I appreciated the farm manager’s perspective and desire to cultivate an agroecosystem that functioned like habitat instead of a sterile environment. Although the choice may entail more work or funding resources, I think it’s important to acknowledge the lasting environmental impacts of some agricultural tools and methods. Native plants nurseries are in the business of preservation and restoration, so it should make sense that they seek to minimize the need that in the future, their cultivation sites will not function as safe habitat or healthy ecosystems themselves.

After the tour at Mt. Pisgah, I helped lead a tour of the IAE farm. I valued this experience since it helped me grow skills in the area of farming no one tells you that you need to be good with- public relations and communication. I explained our methods, the land use history, and the reasons that we are cultivating the species we are cultivating.

We ended the day by touring the Corvallis Plant Materials Center. This operation is different from ours and the Mt. Pisgah farm because it is funded by the National Resources Conservation Service- which means, more research and more funding. I was very excited to see this operation and to learn about the work they do, since it is on such a different level of native plants cultivation than I have witnessed up until this point. While the Corvallis PMC farmers no longer cultivate native seed as their primary objective, they still conduct valuable research on native plants cultivation. My favorite plots were their pollinator seed mix test plots and their Castilleja levisecta (golden paintbrush). I have always wondered about the cultivation of Castilleja sp. due to the fact that many members of that genus are hemi-parasites, and must be grown in the presence of a plant which can function as a host plant. At the Corvallis PMC fields, they grow C. levisecta and Eriophyllum lanatum together for this purpose. I learned that the E. lanatum is first planted, and then followed by the planting of the C. levisecta, I was also fascinated by their pollinator seed mix plots, where they were experimenting with various mixes of pollinator host plants to use for restoration or the establishment of pollinator support gardens. They planted small plots of variations of the same seed mix together in the same area, and it was so interesting to see the differences in growth, plant interactions, and pollinator presence in all of the various plots.

0 notes

Photo

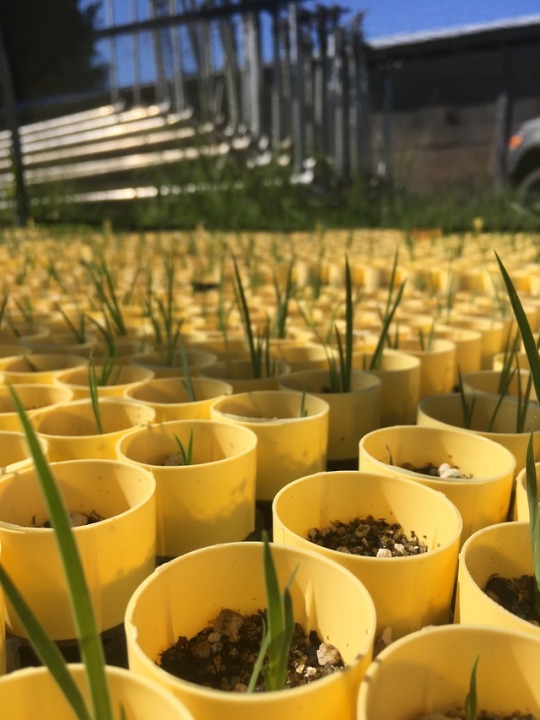

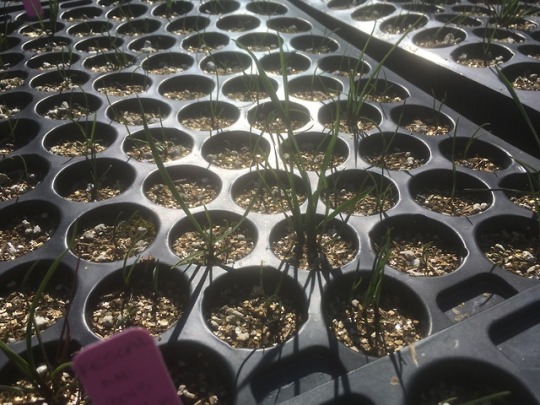

Week 7 (5/13-5/17)

I spent a lot of time this week working in the farm’s shadehouse, tending to the youngest plants under my care. I was busy thinning plugs of Sidalcea nelsoniana (Nelson’s checkermallow) as well as tending to the watering needs of Iris tenax (Oregon iris) and Festuca california (California fescue). The greatest task of this week has been to thin the S. nelsoniana plugs, which were planted in the fall and then placed in cold storage through the winter to simulate cold stratification. I assisted in the removal of more than 30 plug trays from cold storage a couple weeks ago, and have been caring for them since. The seeds germinated less than a week after removal, and so now the priority is to thin the plugs to no more than 2 plants to limit competition and ensure better outcomes for these plugs. These plugs will not be planted at the farm for seed, but will be sent out for a restoration initiative. In addition to my time in the shade house this week, I also got a day of field work. I assisted in an inventory project to collect data on the presence of Viola adunca at Nestucca Bay Wildlife Preserve. The Institute for Applied Ecology led plantings of V. adunca- an endangered plant species as well as host plant for several endangered butterflies- in the early 2000s, and the purpose of this inventory project was to discern the success of the restoration planting. We set up transects and walked them throughout the restoration site, counting each V. adunca plant along the transect.

0 notes

Text

Week 6 (5/6-5/10)

This week’s priorities were centered around weeding beds and applying fertilizer at the field. Using a device composed essentially of a shoulder bag with a crank and wheel at the bottom which open up to broadcast material, I fertilized the entire field with chicken manure pellet fertilizer. I applied 200 lbs of this 4N-3P-2K fertilizer across the field in order to help remedy some of the nutritional imbalances in our soil that we learned of after reviewing soil tests that were done earlier this year.

0 notes

Photo

Week 4 (4/22-4/26)

After a full week of damage control after the floods last week, it was back to business as usual and I was tasked with two more transplantations. At another raised bed site, I planted plugs of Lupinus oreganus. These transplantations are a little different and experimental in that there are already 6 beds of young L. oreganus plants at this site which were planted through direct seeding. The transplants I put in were to fill in any empty areas where germination did not occur. The experimental aspect of this job comes in the fact that L. oreganus is known to not tolerate transplantation well- there is always foliage loss and survival rates are low. However, in a controlled environment, the organization is interested in seeing how many of these transplants will thrive. I did the same type of transplantation at the field, where I planted plugs of Lomation nudicaule in two beds that were direct seeded in the fall. All of the plugs I planted were cultivated in a greenhouse over this winter.

0 notes

Photo

Week 3 (4/15-4/19)

This week’s farm priorities revolved around damage control. As a farmer, you are intimately connected to weather cycles and natural land processes- and you acknowledge that the majority of them are well out of your control. Two important qualities in a good farmer are adaptability and calm under pressure- two qualities I had to develop this week. We spent the majority of this week tending to the field after the Willamette River, which is less than a mile west of the farm, flooded after heavy rains compounded with normal spring snowmelt greatly elevated the water levels in the river. When I first saw the field once the roads were accessible again, I felt extremely stressed and worried. Not only was there a massive amount of damage done to the weed cloth that was installed between every row in the field, but we had just planted plugs of Ranunculus occidentalis and Lupinus oreganus, and I was very concerned about overwatering and root rot, as well as the transfer of herbicides from other fields here at the Oregon State University Botany & Plant Pathology farms that could potentially harm some of our sensitive native plant species. I spent a great amount of time re-positioning and securing weed cloth, and also removing debris from the field. We will see in the coming weeks what this event will have caused in the field, and I sincerely hope that our prairie and alpine plant species will not mind being a little soggy for now.

0 notes

Photo

Week 2 (4/8-4/12)

This week, I spent my first week working with the organization’s raised bed cultivation sites planting transplants of Erigeron decumbens, Willamette daisy. This plant is a listed endangered species, and is threatened by habitat loss, successional encroachment by trees and shrubs in its preferred prairie habitat, competition with invasive plants, and inbreeding within its own species due to small population sizes. There is already a half planted bed of E. decumbens at this site, but the other half needed to be filled in with plugs. We planted the plugs 1 foot apart in rows of four and five. Moving forward this season, I will need to closely monitor these transplants, as they will be experiencing shock due to the transplantation, and will need to be frequently watered since the raised beds dry out quickly.

0 notes

Photo

Week 1 (4/1-4/5)

This first week on the farm, we got right to work with planting. The first task was to fill 6 rows with Ranunculus occidentalis, Western buttercup and another 2 rows with Lupinus oreganus, Kincaid’s lupine. Both species can be found in meadows here in Willamette Valley, but are very different in their growth habits, commonality, and how we must grow them in a farm setting. R. occidentalis is a common, hardy perennial forb- it is a plant you will see growing in high-disturbance areas, and is known to be a tough plant that can withstand a good amount of agitation. L. oreganus, on the other hand, is a threatened plant species in Oregon- it is sensitive to disturbance and has very specific water and light needs. This species is at risk due to habitat loss, competition from both invasive species, successional encroachment from woody plants, and genetic swamping during the hybridization that occurs between L. oreganus and other lupine species. We planted both species in rows lined with weed cloth, using a planting tool called a pottipuki. A pottipuki tool is composed of a long tube with handles at the top and a pedal which opens a pointed beak at the bottom of the tool. This beak, when pressed down in to the soil, creates a planting hole when you step on the pedal and open it. You then drop a plant plug, removed from its plastic container, in to the tool, pull it up and out of the planting hole, and then move on to the next area where a plant needs to be. Another person follows behind the person operating the pottiputki and fills in the planting hole with soil and the planting process for an individual plug is complete. We planted the R. occidentalis in single rows, and the L. oreganus in double rows within each bed. With the double rows of L. oreganus, we were much more meticulous with determining planting depth, distance (between plants as well as from the weed cloth), and alignment. We installed strings along the bed to direct our planting line, and measured exactly 5 inches between each plant before planting to ensure that everything was aligned in order to ease our usage of a combine to harvest seed.

1 note

·

View note