Text

July 31

Increasingly the feeling I am not where I am. A deepening feeling. Immense pressure on a shallow surface. A mezzotint. Intaglio of an imaginary prison.

Feelings from Utah. A glimpse while crouching above the tile. Marbled linoleum. The feeling of distance from that time of life, then trying to recover it. Not the life, the feeling. Because a feeling of distance used to define me. The distance from Provo to Point of the Mountain. From there to Salt Lake. Saturday mornings, pink tint of dawn drawn across a place that was not home but was not far from home. The interval between who I was and who I would say I was. Real affection in the Avenues. It still felt new to be away. A belt of mist on Timpanogas. Answering the phone, affirming I’m OK. Clicking of insects in the trees in the dark. Being able to go back is not the same as going back.

“Life, in fact, is unable to identify with the signs that represent it and can exist only as lack and absence, since in its unpredictability it far exceeds the geometric possibilities of language that can only give an idea of it” (Olvera). But perhaps it is enough to give an idea, a sense. For to give a sense is to give a truth. Benjamin says that truth resists being projected into the realm of knowledge, where knowledge is possession and a system of acquisition. Knowledge is acquired, truth is represented, self-represented, immanent as form, which is a shape, a sense, where form is a “revelation which does justice.” When Benjamin associates truth with essence, and essence with idea, he must be thinking of Idea as eidos. Form here is the same as idea. Idea and form (the real, which is, for the Mannerist, ideal) pre-exists. It exceeds the geometric possibilities of language, which can only give a sense. Which can give a sense.

When Achille Bonita Oliva describes this excess, it is presented in a deviating light, made to feel like failure, overcorrection. According to Oliva, giving a sense is not adequate, is tangential. But the line that Benjamin takes turns truth into a sense. The truth is a given, an idea, a given idea. A giving of a sense.

This is what Sam O says that Melville does when he writes his diptychs, his paired sketches. Between two monads, across the gap or hinge, content that was (is) not there proliferates. For Melville, the form of the diptych is a form of association, associations that multiply, manifold. Two becomes many, more than can be accounted for. Melville’s doubled pairs draw on the energy of “overstatements, exaggerations, volatile jokes, a delight in similitudes and inversions, [which] invite viewers and readers across the borders again and again, encouraging a perverse urge to construe.” Elsewhere O says this is why Melville liked art prints and print production. The print, and especially prints made by Piranesi of his imaginary prisons, are “suggestive,” where to “suggest,” as O points out, etymologically implies “contact with what has been ‘brought up from below.’” The imaginary prisons of Piranesi, are, for Melville, generative patterns that support “the convergence of precision and suggestion, the eloquence of repetition, the distinctive physicality and even violence of technique.” The “far other delineations” that the whale skin gives. The marble in the linoleum.

Far other delineations. The outcome when an idea (a sense, a feeling) is given. The feeling of a feeling that is truth, form, shape, outline. And outline only. A sketch. A draught. A draught of a draught. The copestone left to posterity. There is a posterity.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

[London]

On my last day in London, I elect to journal in the morning, then visit the Tate Britain (chasing some sketches and watercolors by Severn; I saw a number of these at Keats’ house yesterday), then later to the V&A museum with Rebecca.

On the way to the Tate, I took the Queen’s Walk. Got a glimpse of the psychic presence of the Thames for Londoners, as changeful as it is, and wide and used in commerce. Bookstalls and graffiti caverns of Southbank. Saturday promenaders.

I spend most of my time at the Tate with Turner and his impressionistic vortices of light and spaciousness and disaster—an artist whose work has come up often during the course of the Melville conference at King’s, since Melville had an affinity for Turner’s work, and it is further speculated that during is 1849 trip to London Melville even visited Turner’s private gallery. I have made some of my own claims about the lessons Melville gleaned, though at a number of degrees removed, from Turner. In particular, I’m interested in how Turner (and Ruskin) infiltrated American culture and calibrated the efforts of native artists like Cole and Frederick Church. Turner, of course, was affected deeply by Lorrain. Associations of influence abound, which is always a point of interest for me.

A few notes on what I saw in Turner. Known for his history, landscape, and marine paintings (seascapes). A lot of variety in prospect and execution. What is the conjunction in Turner’s mind between these subjects? Landscape as history? The sea as a promontory for human events? I saw Turner’s oceans as inhuman in their outlook—or perhaps, on the other hand, deeply human, so composed as they are of light and air and color, while at the same time implacable and violent. Buoys and shipwrecks. Sea monsters. Disruption, repudiation, or erasure of human form and vantage point. There is still a song to sing beyond mankind, Celan might say, and I paraphrase. Many of Turner’s works would be considered unfinished. The aesthetic appeal of the draft. Yet, historically, this is an artist who appeared to be preoccupied with the downfall of empires, painting and repainting Carthage, Rome, etc. (also Britain, though not in remission). In other words, there is something suspended about Turner’s paintings, something underway, even though inevitable, or marked by a sense of temporal onslaught. Is this Tolstoy’s view? Hegel’s? Wreck and glory. Accretion and light. As with Lorrain, setting up corridors of attention, multiple vanishing points. Conflict or dialogue between the historic-mythic and the daily (as in the hazards of shipping) in Turner, something I admire and want to reproduce in my own work. In his execution, many different stylistic structures: striation, domes, embankment, fanning, rigging. His paintings of Napoleon and Nelson. His paintings of Louis-Phillipe and his arrival and disembarkation, set side by side, as if a diptych, but what was his aim showing these two scenes from the same day of one event? What transpires between arrival and disembarkation? What changes sensibly? Feats of engineering inspire a mood. Love the painting with a view from the Vatican, his depiction of Raphael overlooking Rome, though it is a fictional Rome, multiple points in time layered over one another. Framed by pictures in frames, as well as still life, decoration, implements of craft, and so on. I want to think much further on this work. A small exhibit on Constable, who valorized staying at home as an artist as opposed to traveling, because this is what gave the Dutch their “originality.” Liked looking at Constable’s “Opening of the Bridge at Waterloo.” As with Turner, this is the homespun creation of a British epic vernacular, celebrating the deeds of the British people as if they were myth or classical history. Classic views and ambitions modulating Englishness.

Saw some Blake, too. His “Spiritual Form of Nelson,” as if a single man could orchestrate or machinate the chaos of something like war. He finds his rebuke in Tolstoy. Or perhaps this is the cause of Nelson’s nakedness, vulnerability.

Walked a long walk to the V&A and saw upon arriving an exquisite work by Rachel Kneebone: a column of lower-body parts, arranged in altar panels, legs and genitalia in coral like formation, iterative, replicating, duplicating, human limbs in aggregate organic conquest for space. The mitosis of desire as history. Dantean. “399 Days.” Other items. Monumental wall tombs of Venice conceived in response to the lack of soil for burial. Altarpieces depicting martyrs. The huge Cast Court, and the 19th century interest in copying and electrotyping the great examples of world art. I got to see a massive, true-to-scale cast of Michelangelo’s David, which I was not expecting. An apparent vogue for replicated art, a part of British self-curation of excellence? Along these lines, enjoyed learning more about the pre-Raphaelites and Gothic revivalists, and the nationalist intentions involved with this. Got a satisfying dose of mannerist work—for instance, a pair of ewers ornately adorned with a thick hide of mythic figuration, whose form blurs infinitely with decoration. The mutual subsumption of form in decoration is my favorite aspect of mannerist stylistics. I have to think more about the nautilus shell, decoratively and subtractively embossed, then carved with detailed entomological images—poised between a wonder of nature and an artwork. Various laceworks (flounce with sun and crown motif), ornate instruments, for instance the bass mandore, made of softwood and pearwood. The note in the Wurzberg cabinet: “this cabinet has been completed in the winter months and we would like to go elsewhere, for little meat and a great deal of cabbage and turnips have driven us out of Wurzburg. We ask him who finds this note to drink to our health and if we are no longer living then, may God grant us eternal rest and salvation. This 22nd day of October in the year 1716.” Some of the works of Morris, and the repeating patterns of his wallpaper, his love of the willow. The prevailing sense throughout my visit that I am audience to the treasures of the Western world. Much of human ambition and passion and idiosyncrasy on display.

On our walk home, Rebecca and I find 25 Craven street, which is where Melville lived in 1849. We said goodbye under his sign, and it was a fitting conclusion to the trip.

A short reflection on the trip as a whole, as I fly from Heathrow to JFK:

In the search for continence and continuity, to dwell in a place is an important part of establishing an epistemological framework. To come to know in the world, one has to be located somewhere in that world, so viewing by the principle of parallax. This is what Turner deprives his viewers of in his masterful, anchorless seascapes. I have carried Thoreau with me as a kind of unacknowledged patron saint during my travels, and he above all voices with characteristic stridency the benefits of laying local foundations, digging out the earth with your own hands to build your own hearth. But there is another perspective obtained in travel, especially for an American going eastward. On this trip, I saw glimpses of the receding geology of history—the strata of sediment upon which the present is built. I am obliged to dig, yes, but to core or tunnel to build a home is to miss out on the cross-sectional perspective that is afforded by leaving home and looking back at it (and yourself) from a distance (even a Cassandralike distance). In England and France, the landscape of time and history is uneven, channeled through or carved out in places to reveal an underlying geomorphic theater. The lesson is that we live out our lives and our happiness in ruins, the kind that Hubert Robert painted, peasants and pastorals still flourishing and living out their lives in the shadowy receded bay of empire. What I witness during travel are these principles of uneven flux and combined, combining metamorphosis. More particularly, I have observed and given myself a crash course in two cultures: the life of the Londoner and the life of the Lyonnais. With regard to the former, I have observed the costs and benefits of the “global city,” the over-densification or hyper-distillation of history, the ensuing memory overload that the urban landscape seems to register. When you have wealth, you have the future, and when you have the future, you have no need of either present or past, since the past is a positive frangible antique and the present is a dream space for visions of the future, which can, exposed to the versatility of human invention and fancy, be or become anything. In the global city, there is history everywhere, but no sense of locationality or historical sympathy. Temporally, the global is provincial and provincializing. In Lyon, I found a marginal or secondary city. An echo city. A younger sister. The ways in which the blind savage event gets registered in the relative backwater. Binaries are exacerbated or put into relief here. The hill that works, the hill that prays. The labor revolution, the intellectual revolution. Vichy and de Gaulle.

The highlights: many poignant experiences at the foot of masterpieces of art, new and old—the fragments of the parthenon, the Portland vase, Schoendorff’s painting, Janet Cardiff’s figuration of Tallis’s motet, a morning with Turner; the panoramas and vistas I encountered—views of Lyon from the Gallo-Roman ruins, from Fourvière, and of London from Parliament Hill in Hampstead; beautiful gastronomic experiences—the soul-sharpening, distillating dinner at Oxford, the Lyonnais lunch; finding vortices of time and tide—the grave of Milton, the Bartlett School of Architecture. Feeling extremely small, vulnerable, fragile in the face of all this. Ludicrously anachronistic. I cherish the micro-transformation I have experienced: from a turn toward the epic to a turn toward the elegaic. That is, from scope and scale to witness, though sometimes that testimony does not come through in words, but in the breaking of the will and the body.

/

final thoughts on Absalom, Absalom!

What I read abroad is a decision I leave up to the place and the experiences I have in it. In this case, while reading the Jameson article in the London Review of Books on my flight to Heathrow, I encountered a quote from Faulkner’s Absalom, Absalom!, describing the somatic mechanism of remembering. In this passage, that description is framed by and spliced into a fragment of narrative discourse (“Once there was—”), and the ensuing deconstruction of memory into mere or simple experience of substance and embodied interaction with that substantial materiality, as opposed to some reservoir that exists in abeyance, held back, but is not triggered but instead is activated on the basis of desire and need and body and the rememberer’s presence vis-a-vis other presences. Memory is not had, memory is summoned. But it is summoned by no conscious agency, for agency so configured is not conscious, for the agent is a collocation or confluence of forces, for the person and the agent has their ipseity in inertia, in movement and movement’s redirection by embankment and sluicegate. If there is one category that is eroding for me it is the category of agency. The question of free-will once resided in a theological register, but now the question of free-will must be framed with respect to economics and complexity and intersubjectivity. Less a hierarchy (or tree), than a rhizome.

As I see it, the main dramatic scope of Faulkner’s book has to do with the effects of witness and the transfixion or arrowing through time of human action. It is about the ways in which we fate or doom each other to “backwaters of catastrophe.” Just as the sun distills and hyperdistills on the first page of the novel, so the light and shadows cast by individuals distills and hyperdistills through time and space. No one is being or entity in this novel, but commonwealth. In this way, the book was apropos of travel in England and in France, where the question of commonwealth and social living finds voice more often than in the United States—and it is a disturbing notion that American access to this question might have to be through the gate of the Civil War and the shuddering trauma of that event as it continues to propogate or to hyperdistill. “Maybe nothing happens once and is finished.”

Wisteria appears and appears in this book, mote by mote, and it grows not by principle of root and light but by principle of progressive revelation. Progressive revelation as garlanding, and the garland as an icon of listening and of crowning, and what is crowning but a breaching, an emergence. Flourish as realization. The phenotype of events. Faulkner talks about the “forced blooming” of certain characters, particle by particle into the gloom. And of course, the effects of this forced blooming are wrought on us by others, others are that sunlight that goads the seed, and Quentin is that impacted stamp of earth where a seed was put, a minute deviating hyperdistillation, and it is in Quentin that the reader sees the irrevocable soul-damage of witnessing and then also the attempt with language, that meager and fragile thread, to reconcile though the effect is only to further trammel and trammel also others in the marionette and fated netting.

This is a book of astonishing historical vision and is my gatekeeper into the south: a hinge that was given me by travel to the UK and to France, and the vertigo I felt there when I tried to feel the transfixion of the arrow of deeds as they pierce me through time through a place.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

[London]

What follows is a description of thoughts and sights from the 26th to the 30th of June.

The hybrid forms and architecture of London has a psychic effect on me. I have a sense of historical saturation and velocity, at deep odds with one another. Every corner and close and cranny of the city is a time-and-stone vortex. Notice the skyline’s deliberate repudiation of symmetry, and unintentional repudiations of all kinds that we make by forgetting, by advancing in space. Boats, however, still need to tack laterally to dock, and you can see the ancient seats of the ferrymen tucked still between the banks and the Greek bistros. As an American, and perhaps all Americans have felt this way, all I have is vicarious geology—though this seems, too, to infiltrate cultures of my longstanding earthly presence, like England. Notice that the Thames river once was more permeable to city and vice versa. During the 1850s. Whales found in the Thames, chased and killed. Notice as I cross bridges in the morning that the levels of the Thames have fluctuated since last night. A dynamic, responsive entity. A nonhuman vein through this hyperrational framework of glass and steel and history. The new situations that arise each day in clusters and bunches. Smell of particle board across from St. Le Mary. Man playing a sheng.

I appreciate the green spaces in this city that have been commissioned in the ruins of pastoral architecture. Chapels or cathedrals like Greyfriar’s and St. Dunstan’s in the East have been transformed into public gardens in the aftermath of the blitz. Flower beds and growboxes are arranged where pews and pillars used to stand before the bombing-out. Incindiary violence has lifted the carved roses and climbing clematis off the columns of the churches and realized them into life. Violence as the catalyst for proliferation. Part of the “Pastoral reorganization measure.” Ruin as trellis, but for growth of what kind? What grows in these spaces, apart from plant life? Memory?

I visited John Milton’s grave, which is fringed by a fragment of the ancient London wall. It is completely hedged in by commercial development; the London wall has been re-walled-in. You have to cross a sky-bridge and pass a Pizza Express to get to St. Giles-without-Cripplegate, which is where Milton is interred, along with Martin Frobisher, the 16th century explorer. Oliver Cromwell married here. When I arrive at the church, musicians are preparing for a performance. There are pots of herbal tea and instant coffee on folding tables. Book sale shelves. Outside, there is a brick terrace or esplanade where the church yard was once. Willow branches stir across the mortared surface, gravestones have been displaced and laid almost as tiles in raised areas of the terrace. Many of them have been almost completely effaced. I stood over them and bent to clear away the moss and bird droppings, looking for Milton. I understand he is at the foot of the chancel steps, but I don’t realize, until asking a passing vicar, who, over her pastoral collar and garments, is wearing a crepe, floral print robe, that a chancel is inside the chapel, and I snap a photo of Milton’s headstone, on which a musicians in purple Converse sneakers is standing.

Nearby you have John Keats’ birthplace at the Hoop and Swan, a pub now called Keats at the Globe. It is adjacent now to a Harpal or anti-aging, Clinic. Skincity. Hormone optimization therapy. Chemical peels. Microneedling.

A brief visit to the London museum, where they host an exhibit on the torch mechanism for the most recent olympics and the London stone. I realize here that I don’t care about prehistory. I care about history, which means I must care about historiography above all else.

I meditate on “finance poetics.” Mine is an inherited world of speculation. Values are created and sustained discursively, as opposed to on a gold standard. As a poet, or an elegizer, do I not speculate on someone else’s glory, immortality, when I write of other writers, and their influence on me?

I visit Regent’s Park with Katie, who I met at Luxembourg last summer. After some difficulty finding one another at the Baker Street station, we meet at a tennis club in the park. She tells about her research on Joseph Paxton and the Victoria amazonica, a massive Guyanese lily and an icon of the performativity of empire in the Victorian age. We talk about the role of the academic and our shared sense of anxiety (about youth, family, future) in a garden of roses in the sun.

After visiting with Katie, I stop in at the Bartlett School of Architecture, where there is a summer show of student work on display. A several-story gush of architectural models, the delicacy of of their balsa and cardboard, their extruded printing material. Video games and VR. Supersaturators. Building skin. Preservation, intervention, and augmentation using Venice and Hamburg. Habitable space within territory. Data landscapes. Artificial experience of human sensitivity at high altitude in the Andes. Meaningless specificity. Spontaneous and ordered structures juxtaposed. Coliving lifestyles. It is a completely overwhelming experience, alienating. I am forced to consider my anachronistic place in the world, and, young as I am, confront the sense that I have no control or influence over the future or built environment that I will inhabit.

Overheard at Fabrique, two, young British women speaking, very quickly: “Ethics aside, all jobs have an unethical element.”

I am thinking about paintings I have seen by Hubert Robert, who depicts pastoral and rural folk living among the ruins of bygone empires. In whose ruins do we live?

I meet Rebecca at the Cheshire Cheese. Hung from the rafters of the pub, porcelain, pottery, tankards, decorated with scenes and clusters of berries.

Notice the droves of bicyclists, the cyclist superhighway, some wearing face filters to block out the exhaust and pollution.

I visit the Poetry Library, but in order to do so, I have to elbow my way through a massive (high school? university?) graduation ceremony at the Southbank Center. Wealth, youth. Somewhere buried or deep or high above all this a library of poetry. I notice a girl with an infinity symbol on her neck, Sam Smith sneakers. The elevator doubles as an art installation that sings out the floors as you ascend. In the poetry library, an exhibit on Piers Plowman. “Fair field full of Folk” is an apt description of London.

The Melville conference has begun, at King’s College London. Old faces. I learn about Melville’s relationship with the painter Turner, and Turner’s pictures of whalers. Art in the age of ironclads. Criticism’s agency is abstract. “Historically dense but deliquescent”—said of the work of an artist who presented on Melville’s experience in mid-century London. His talk at the British Library, where I wrote for a while. This artist spoke of Admiral Horatio Nelson, his relics, on his clothing the wax and sweat and blood-stains. “Compassion has real consequences.” Luciano says “Melville studies is concerned with world-making.” At one presentation, the phrase “slow violence,” and the question, at what point is violence narrativizable, and thus visible? I feel the work of writing and poetry is to narrativize forms of slow violence in the world.

The first night of the Melville conference, I have dinner with Christine at the Samuel Pepys pub. We talk about contemporary life and poetry, and the deeds we feel we need to accomplish to assuage guilt in the dying empire. Maybe the best we can do is reciprocate need and fulfillment of need among others. The question becomes not what to do, but what to do with my complicity (agency). Networks comprised of navigating complicity and compassion.

The astonishing warped column at One Blackfriars. Leviathan. I consider that true, old wealth insures itself, buttresses its existence against time. Apart from these massive high-rises filled with million-dollar real-estate, what are the new monoliths of civilization? Are they financial, speculative? Can a scheme be an edifice? Can an algorithm? Are there abstract forms of monument? What is glory now? I feel like the Cassandra of Bankside: blind, baffled, eclipsed by visions of the future that are beyond my powers of articulation. In fact, there is a stone sculpture of Cassandra’s face at the NEO bankside development, in a sculpture garden. An icon of my stay.

With Hutch and his son Gabe, I get to see the Globe’s production of Twelfth Night. The reconstructed Globe has a roof made of a special kind of fire-resistant thatch. The play is a true spectacle. Bright and bombastic and fast-moving, Vaudeville. Scottish drag and disco as the costume setting. At its heart the text seems to concern itself with the indirection of love as an epistemology, the epistemology of competing desires. “I wish you were what I would have you be.”

A visit to Hampstead and Keats’ House, or, more properly, Charles Brown’s house. Enjoyed looking at his marginalia in Burton and Spenser. Enjoyed reencountering the painter Joseph Severn and his devoted friendship. On the green outside the house, I sat beneath the plum tree under which it was purported Keats wrote “Nightingale.” Here, Keats’s Beechen green and shadows numberless, lush with summer. Elsewhere on the green, wrestling schoolchildren, practicing lines from Romeo and Juliet. Along the landscaped border: Queen of Night tulip. Gingko. Forest pansy shrub. Inside the house, sparse artifacts, decorative fake fruit. Enjoyed looking at some of Severn’s watercolors, those he painted on the crossing to Rome. Looked at the Regency-era plumbing and rain-catching. Looked at Severn’s marvelous brooch. Saw that perhaps Sosibios vase is the vase in question in the “Urn.” In a neighboring library with a beautiful stained glass-dome, saw a handbook for gardeners called “Enemies of the Rose.”

Rebecca and I afterward got lunch (several slices of bread at a bakery for me), and ate in and wandered through Hampstead Heath. A truly breathtaking view of Parliament Hill. Rebecca told me a story about her search for breadfruit, which Melville describes in Typee, and all the people she met on her search for this food.

Afterward we went to the National Portrait Gallery. Some notes I took: Alone in the problems of her responsibility. Other faces in a portrait (especially artificial ones); Counterposed figures, group portraits; Charles Ricketts, oblique profile, hands in rags, ascetic beard, dewdrop flowers, Roman numerals; Late Victorian, pre-Raphaelites; Hallam Tennyson with hoop rolling stick; Launching chains, ocean steamship “Great Eastern”; Textures and personhood; Direction of gaze, angle of posture, head; Details from the dresses of Elizabeth of Bosnia, Elizabeth I; Samuel Pepys holding his own composition in hand; Milton’s girlish fairness; To have a living person as a “muse”; “Enjoy the luscious landscape of my wound, but hurry! time meets us and we are destroyed”; The death of Earl of Chatham by Copley, naval wallpaper, Christological trauma, adoration, public perception / reaction / grief / decorum; Somerset House Conference; Sute of russet satten and velvet welted.

While I wait for Beth Schultz at Trafalgar square, I read some Faulkner, and the line: “Maybe happen is never once but like ripples maybe in water.” In front of me, Nelson’s column, Nelson facing away. A melancholy girl at the fountain, orange hair, listening to music with earbuds, sitting very still.

Met with Beth at the Edith Cavell memoiral monument. I’m working with her on an anthology of poetry about Moby-Dick. Went to a cafe, restaurant, wine bar called Notes. Beth is charming, and exudes an admirable love of life and generosity of intellect. We spoke of poetry, friendship and pleasure parties, and our lives. I feel suffused with good will. On our way back home, she stops at a shop filled with Japanese treats and deserts, and we reminisce on similar treats during the Tokyo trip.

On the last day of the conference, we went to Oxford. Took charter buses. On the way, from the freeway, seeing the charred column of the Grenfell tower. Nearby, a building advertising “imperial thinkspaces.” We were given a quick tour of Oxford campus, which is ancient and infused with a solemn sense of monumental knowledge. Strange grotesque or gothic faces adorn the corners, cornices and walls on the building exteriors. Features as feature. I have several wonderful conversations, including with respected Melville scholars. They are kind to speak to me. During dinner, which featured gorgeous (though surreal—something contrived about the anachronistic portraits and samplers of wealth to which I am being exposed) prelude music by Schubert, I sense myself locked in with intense focus to the conversations in which I participate. The menu: Sesame marinated tuna and ginger salad, pickled leek and baby corn, soy dressing. Three pepper marinated rib-eye of beef, heritage carrot puree, tender stem broccoli, crushed potatoes and spring onion. Strawberry soup, lemon verbena jelly, mint sorbet and honey madeleine. Baliol mints. Truly a treat. Good will felt by all.

1 note

·

View note

Text

[London]

Back now in London. Began the morning (at 3:45) with an Uber to Part Dieu, where I saw a fight break out between two Eurotrash lotharios, skin-tight shirts, stonewashed skinny jeans, man-purses, pumas. One of them dismantled a trash can and tried to brain the other with it. A companion tried to hold them off, then surrendered, and sat with his head in his hands.

Airport security, and its muffled choreography, is one of the sure signs of empire in decline.

Most of the morning was an attemp to stay awake.

Once I landed, I wandered through Borough Market, saw the old Winchester Palace with its freestanding rose window wall, saw the old site of the Globe theater, saw the old apartment John Keats lived in with Henry Stephens when they were studying as doctors at Guy’s Hospital, who helped Keats compose the first line to Endymion: “A thing of beauty is a joy forever…”—and then went to LSE Bankside to check into the dorm room where I’ll be staying for the next week. It is directly across from the Tate Modern, which I can wander into whenever I have the impulse. An exquisite piece by Janet Cardiff: 40 speakers arranged in a circle, each playing the individually recorded voice of one singer in a 40-part motet singing a Tallis choral work called Spem in Alium. You could listen to any voice you cared to up close, appreciating the full contours of its individual role in the unity of the song. A truly immersive, architectural experience. Loved Lenore Tawney’s Lekythos, a linen weaving, distended, frayed and sparse, in the shape of a narrow-necked Greek vessel. Mediums describing mediums. For art to seek to attain the status of the vessel. Noriyuki Haraguchi’s “Airpipe C,” swooping canvas shaped like a jet engine, the jet being what Haraguchi cites as the breakthrough moment at which point he came to understand the “true nature of creativity.” Aesthetics and industry (and war).

Then walked toward the Moleskine store across the Thames for some new journals, enjoying the hybrid archiecture of the city, the hard, exoskeletal, bristling lines of London’s speedways, the baroque domes of its past. London looks good in the overcast, the Thames roughened by wind. It is as if, after Lyon, I have returned to an entirely different city.

After purchasing some notebooks, I go on a note-taking spree, recording overheard conversations (about fox and pheasant-hunting), wondering do we still do big things, thinking about sustainability and its cult. Saw sculptures of Cassandra in the courtyards of apartment complexes.

Enjoyed pawing through cheap art books at a shop across from the Tate. Hid a few books on the Dutch and Flemish masters that only I can find if I decide to buy them later. Another sure sign of an empire in decline: that one of its citizens, a young man of 25, should love the Dutch and Flemish masters, baroque merchant class that they represented.

The redeeming function of being a parent and having a child: the new question in your heart: what kind of world and fortune am I leaving behind, now that I leave behind a child also?

Early sleep.

0 notes

Text

[Lyon]

On Saturday, the day before I leave Lyon, I decide to pursue a real lyonnais meal, having failed in this attempt the night before, winding up after a long search for a dinner in my price-range at Le Churchill, a PMU bar, run by a husband and wife, foreigners themselves, who encouraged me to get the “American” sandwich, though instead I asked for the ciabatta and sausage, and was sorely disappointed by the soft ciabatta, meager sliced meat, butter and pickles, and tried to mitigate my disappointment by calling the evening’s meal the meal of one who lives and works in this place, for whom a sandwich is a pretense for fuel, though I am precisely a tourist, and not even remotely a local. My plan is to do lunch at Comptoir du Vin, and so I write in the morning (after walking around the neighborhood, a lunette for breakfast at the bakery, airy texture of powdered sugar) and then read for a while at the terrace overlooking the city beside the Gros Caillou, a local landmark: a large rock purportedly deposited there by a glacier from the nearby alps. It serves as a symbol of the annexation of Croix-Rousse into Lyon and of the perserverence of the inhabitants of Lyon. It was unearthed during the construction of the funicular system, a slanting, upward climbing tram-system, over 150 years old. This location is also where Jean Moulin was intercepted by the Gestapo, then tortued to death and thus martyred for the French resistence.

Lunch at the Comptoir was delicious. I was served a plat du jour: saucission cuite, a traditional lyonnais dish, comprised of simple, staple components: hot lyonnais sausage, roasted potatoes, carmelized onions, butter, parsley, and an oiled salad of fresh greens and garlic. Served with a side of bread. Since I was first in for lunch that afternoon, the server (dressed in a t shirt and shorts) had to cut anew into a big canoe of bread. The windows of the restaurant were decorated with a yellowed skein depicting clusters of grapes and cups of wine. A man enjoying a cup of rosé at noon at the bar when I arrived. Disco plays in the background.

After lunch I walk to the Musée des Beauxs Arts for a second look at “Hymne 1967-69” by Max Schoendorff, thus consecrating and sealing the day as a day of indulgences. I took my computer along so that I could write about the painting there in front of it. Encountering it again was not as moving as before, but I stayed with and studied the piece for about an hour, listing words or phrases that came to mind as I looked at it: Reticulation. Remission. Bundling. Bone deposit. Bone growth. Sliced salmon. Embroidery (Salmon embroidery). Nodule. Shroud. Coral. Nude. Pectoral. Meridian. Apotheosis. Skin-bound. Canalization. Clotting. Bowel. Skin-toned. Reflective. Self-reflexive. Dove immolation, imbrication. Angel hoof. Cuspid. Calcification (Cusp calcification). Water damage. Flange. Baboon. White bat breast. Thrapple. Tress. Trestle. Aorta. Pulmonary. Sojourn. Cardiac. Melting foil. Candy wrapper. Lozenge. Styrofoam. Haunch. Development. Dewlap. Raw angel. Gristle. Cartilage. Crotch panorama. Tissue. Cottonmouth. Bifurcation. Swan webbing. Carotid. Corrupt. Cormorant. Nereid. Trot. Nemotode Kingdom phylum class. Lipid. Fatty acid. Nucleic. Blood iris. Femur. Tibia. Emulsification. Pulchritude. Aural. Emote. Lilith. Adamic. Pagoda. Tenterhook. Tenting whorling. Effluvium. Fluvial. Torso. Loophole. Lunged. Torrid. Torpid. Turgid. Flaccid. Taffeta. Liver. Megafauna. Megaflora. Buildup. Snout. Osprey. Thaumaturgy. Edify. Eddy. Glut. Rugrat. New Year. Breastbone. Clavicle. Soothsayer. Judith. Pelvic. Pubic. Tastebud. Rosebud. Lick. Mouth. Corpuscule. Crepuscular. Miltonic. Cilia. Croupe. Flute. Fluting. Pearling. Marbling. Chambering. Corruscate. Maidenhead. Blaspheme. Blooded. Blastocyst. Tumescent. Tumor. Floodgate. Noogie. Hot ear. Napalm. Flavinoid. Fistula. Foment. Zygote. Amergris. Rib light. Deterritorialization. Reterritorilization. Salvo. Salvific. Slaver. Feedback. To skin. Gladiola. Begonia. Peonie. Vulva. Silken. Silk worm. Desiccate. Roil. Dragon. Onyx rooster. Emergence. Scalene. Vector. Oak-bred. Parakeet. Fluency. Predator. Celiac. Gluttonous. Emperor. Later, overlooking the city in the shade of the theater ruins, I wrote the following prose fragment after the painting:

oak-bred, silkspun a kingsfold of calfsears, then fever-eared though hand-draped, though these too shall marble off the breast, the pectoral meridian, for we self-suffer, as in turn in and in, reticulate, tenting the crotch, fluting the carotid, a floodgate of floodgates, yet the part in the father’s hair was a part too in that veil, nodule-brocaded, his father a rumors-of-war-lord, coveter of that that was already his, and so by law of spandrels his son’s own cross-walling, cusp calcifier, his inheritance a bonespur and a flaccid aegis, unflagging ear drum

Looked at some of the other contemporary art I didn’t see at the museum earlier in the week. Enjoyed also the Vases de Beauvais by Horace Bieuville, beautifully glazed with a crystalizing lapis lazuli.

Also today saw the old site of the Condition des Soies, whose portal archway has in iron relief branches of mulberry and little wriggling silkworms.

Thyme added to green tea.

0 notes

Text

[Lyon]

After writing on Thursday, I went out along the riverside to read with the sunset, day after the solstice as it was. Strong wind off the Rhône, skipping or flagging across the ear. Lots of young people out, kids that look no older that 16 drinking cases of European beer in the parks and playgrounds that hedge the river. I sit by the Passage du College and read my Faulkner until the light too much dims. Maples everywhere, shedding, you can hear them shed in rattling strips as you walk, and some of the maples are sprayed with graffiti and shed that, too.

The next morning I plan a long walk into some of the hinterlands of Lyon, which is my wont, and walk through Parc de la Tête d’Or on my way out to Parc de la Feyssine, with the intention of going further, into the great swathes of green space my map shows. In Tête d’Or, I visit the Isle of Memory, which is dedicated to the 10,000 dead Lyonnaise in various 20th century wars. Pass through a submarine tunnel to get there. A heavy statue of men and women carrying a slab with billowing draped cloth. A revealing sign dedicated to the fighters who died for France “en Afrique du Nord, 1952-62,” referencing the Algerian war (though pointedly not validating it by calling it such). Parts of Lyon, indeed, were constructed to house les Pieds-Noir, French refugees displaced by the Algerian liberation. This is a sign of Southern France.

I leave the park looking for food, drift across the campus of the Institut National des Sciences Appliquées de Lyon, then into the Tonkin neighborhood, a quarter of the Villeurbanne city, “limitrophe de Lyon.” As a suburb of Lyon, it was established in 1894, the same year as the Exposition universelle, internationale et coloniale, and as a result its streets and quarters are named after French colonial capitals, Tonkin being an example, a city in Vietnam. It developed a working class suburb, a texture maintained today. I find myself wandering through a what seems at time a hospital clinic campus, a primary school, a market square, all blurred under the banner of social housing. I have a croissant and fruit at a cafe that feels like an outpost in the middle of an interlinked domestic sprawl. Strangely intimate to be there, and thus totally defamiliarizing. After my dégustation, I pass by the Esplanade de l’Europe Jean Monnet which features a surreal rubble sculpture of ruined, fragmented, monumental statues called “La Fontaine des Géants.” Monnet is considered one of the founding fathers of the European Union and has been called the Father of Europe. Curious pairing of the statue with the Esplanade so named. Monnet was also charged by de Galle in the post war years with modernizing France. Everywhere the postmodernist working class blocks of apartments and housing.

Back into the green spaces in the north. Parc de la Feyssine. I sat beside the water to read. Such an aquamarine, almost chlorinated color to the Rhône, quite unlike the choppy brown of the Thames. It is good to have this diptych of rivers to consider. The water, while not clear, is vibrant and pure looking, and I recline on the smooth white stones that comprise the beach. Bathers. People tanning. Yet company is sparse. I imagine the scene from Camus’s The Stranger, in which an act of arbitrary violence occurs beside just such a placid body of water, and I imagine for a while what that kind of incursion, flooding in then out as fast, might feel like if it were to happen to me. I take the tram out to the Musee Gadagne, which is dedicated to the history of Lyon. A Gallo-Roman settlement, it eventually became the pet urban project of Charlamagne, who placed a bishop in charge of governing the city. Lyon, off the beaten track, ebbed and flowed along the more turbid course of empires and regime change, sometimes forgotten, “sans roi, sans duc, sans prince.” At other stages of its development, it was a city known for its production of playing cards and harpsicords. Points of connection to my walk from tramstation to the museum, where I passed a clavicord shop and saw in the window a deck of playing cards called, translating the French, “patience cards.” Stained glass of the poetess Louise Labe. Noseless bust of Henri the 4th, my favorite historical king, who also exercised his dominion over the city in impressive ways. Henri and Marie de Medici married in Saint Jean Cathedral, which I visited afterwards and saw through that lens. More exhibits on looms and weaving. Learned that in the 20th century, the mayor of Lyon, Herriot, in power for almost 50 years, commissioned the desing of major amenities and social housing, including in the factory city of Villeurbanne, through which I had drifted earlier in the day.

At the cathedral Saint Jean, a beautiful astrological clock, ornate and multi-tiered.

And throughout the day, the tolling fated stream in Absalom, Absalom, set in the backwaters of catastrophe, a vision of the rending of agency from the hands of those alive in marginal areas, post-catastrophe, and the small quakes that continue to echo through those lives. I find myself strongly identifying with the character of Rosa Coldfield, described as being “Cassandralike.”

0 notes

Text

Day 7

A good and a complete day. In the morning, I cast about the neighborhood for bread, brought some home, and made, with butter, my breakfast and my lunch out of it. As I was out, I explored further the crooked, beautiful montées in my neighborhood, the 1st arrondissement, which is known as les pentes, or the “slopes,” of La Croix-Rousse, the north hill: “the hill that works,” as opposed to “the hill that prays,” Fourvière hill. Respectively, these appellations refer to the silk industry and workshops in the north and the large basilica on the west hill. The montées throughout Lyon are long, steep staircases that crimp and pivot like squash vines. They seep with extensive, elaborate, and often sentimental scrawls and cornucopia of graffiti. On my way home today, coming from the Fourvière neighborhood toward La Croix-Rousse, there is painted on the wall of the stairs a series of questions, written separate of each other: “Oui ou non?”; “Ce qu’il y a à voir?”; “Qui cherches-tu?”—yes or no?, what is there to see?, who are you looking for? With the first question, an echo of the judgement of Paris.

Views on my way home from Place Bellecour. The red roofs and tall chimneys of the skyline, and glimpses of the Rhône.

I wrote all morning and left the house around noon for the Maison des Canuts, a small museum that details the tradition of silk weaving in the city. I learn about the Condition des Soies in Lyon, a process of standardizing silk weight and pricing. An apparatus called a talabot was developed as a kind of dry oven in which silk pods were desiccated for a period of time and then weighed. The scales and oven double. Propaganda posters instructing French farmers to plant mulberry trees on the borders of their fields, in order to increase silk production. Many of the looms I saw use punchcards that control the placement of machine-run needle and thread. To create fabric, machines employ a dynamic dimensional grid of weights, pulleys, shuttles. How to make gold thread. A brief exhibit on Pasteur’s role in sericulture, or silk farming. The jacquard loom, and the rise of the “luddite,” a group of English textile workers who worried their craft would be replaced by machine automatization and rose up against the machines in the 19th century. Curiously, the jacquard loom employs the same punchcard system that eventually developed into the first computer. During the 1830s, at least two violent revolts by the canuts, usage of the traboule, a type of passageway associated with Lyon and devised to transport silk products. Facilitated quick movement from the top of the hill to the lower portions. These rebellions, precipitated by price fixing quarrels, were among the first organized worker uprisings of the industrial revolution, and even involved a weekly eight-page newspaper. After looking at looms, I followed an extensive traboule, from the top of La Croix-Rousse to the bottom, passing through numerous domestic courtyards on my way. A flag woven by the canuts in 1831 reads: “Live working or die fighting.” Hugo describes the revolutionary spirit of the 30s by comparing Paris to Lyon: Paris, the city of thought, experienced a civil war; Lyon, a city of labor, experienced a servile war.

Caught in a trap by the Musée des Beauxs-Arts. Read for a while in the hot courtyard. Looked at the extensive Rodin collection: bodies entangled and sprawled in anguish: “Paolo et Francesca ou couple damné”, a sculpture of Narcissus dead, “The temptation of Saint Anthony”: a naked woman sprawled sensuously over the huddled body of a monk. It is difficult to tell apart the postures of despair, anguish, ecstasy, and death. I had a hard time looking at the antiquities in the museum. I have zero affinity for Egyptian artifacts. Nothing could be more boring to me. However, the detail of drinking birds and grapes on a lead Roman-Syrian sarcophagus was a foothold. A beautiful Bavarian bas-relief tableau of the last judgement. I resolve that epic and scope might be the only aesthetic worth pursuing and thinking about right now: “The Palingenesis of Society” by Chenavard; the massive Rubens depicting an angry Christ, Saint Dominic and Saint Francis preserving the world from his wrath. Two important discoveries in the museum: 1st, a favorite still-life of mine, Mignon’s “Bouquet of Cat and Mousetrap,” reminding me that the pursuit of hunger can engender precipitous (ecological) collapse; 2nd, perhaps my favorite piece of art on the face of the planet: Max Schoendorff’s Hymne (1967-69). I have never seen a more moving portrayal of the human body, and its capacity for the elision of flesh and abstraction. A panorama of the figurative, spliced with textures of coral, gold, desire, cat’s-mouths, marbling, foil, enamel, stomach-lining, flesh abstracted, nereids, nematodes, ribonucleic reticula, butcher-slabs, sex, the pubic, the pelvic, exposed hanging meat, Francesca and Paola: a maelstrom of materiality. A textural epic. I would pay to go look at it again. Schoendorff was a lyonnaise painter, it turns out.

Next I make my way up to the basilica, picking up ingredients for dinner along the way: salad components and a pain au chocolat. I eat the salad, deconstructed, in front of the basilica on Fourvière, which has the most incredible, exquisite view of the city. Truly one of the most superb vistas I have ever seen. The cathedral is staggering as well. So many carved wings. The whole edifice is in flight, yet dense and encrusted all over with detail. Such density of detail, enshrinement in it. I tour it twice, and look at the spectacular mosaics of the cult of Mary and the deliverance of Lyon by Mary, time and again. Priests carrying buildings in their hands, a piecemeal city.

I walk home, enjoy the smell of the cooling summer heat.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Day 4, 5, 6

I have been unable to find time to write for three days. I have written, but not in a diary. After seeing the National Gallery in London on the 19th, and after looking there at the anonymous Flemish painting “Cognoscenti in a Room Hung with Pictures,” I have been eager to work on a world that takes after that piece. I am compelled by the desire that has precipitated it, an epistemological thirst. It is a painting that wants to be several paintings; it tries to contain, index, profile. If each painting inside this painting is a logic and a world, this work worlds itself with these as its lineaments, acknowledging the work of art as more than subject matter: as matter itself. Art retro-architects reality. “Cognoscenti” is essentially a form of praise, too, showcasing the virtues of appreciation, abundance, knowledge, and the limits of knowledge. I want to write a series of embedded essays that work chiastically through world, into art, and back into world again, showing the ways in which transferences redeem the real. Mediation is reality—or rather, reality is always already mediated.

I will return to the National Gallery. I have to take this slowly. Monday the nineteenth begins at Abney Park, a cemetery in the Hackney borough in which I am residing. I am brought here by a book I’m reading called “Lights out for the Territory” by Iain Sinclair. My new unofficial handbook to the city. It perverts the figure of the flaneur into that of a stalker. My walks are like Sinclair’s in this: anxiety, hunger, and paranoia gyring into each other, a sense of non-belonging, voyeurism. I am here to observe, subvert, contain, vivisect. Sinclair’s walks through Hackney take him to Abney, where he notices a spray-painted pyramid-and-eye symbol scrawled in an unused non-denominational chapel at the heart of the park. I’m there before nine and it’s already broiling, one of the hottest days on record since the 70s. The inside of the cemetery is overwhelmingly green, dense, clotted with grave stones. Arborists and wood-cutters haul machinery through the overgrowth. What is overgrowth and what is undergrowth and what is a memorial to the dead is impossible to disentangle or set straight. Everything strays here. Death is no straightforward terminus. Indeed, one of my favorite aspects of Abney were the signposts scattered throughout identifying the various trees on site. The signs record the curious and mazy longevity of silver birches, common ashes, service trees of Fontainbleue, and horse chestnuts, among others, as though offering veiled metaphors for grief and earthbound afterlife: “SILVER BIRCH (Betula pendula, planted around 1930) / This tree appears to have been struck by lightning about 30 years go. It is not know exactly where this avenue of birch trees was planted, but birch rarely live more than 100 years. Lightning is the most likely cause of the long wound down the north side of the tree. You can see decayed wood inside, with fungi and beetle holes. Healthy wound wood has grown around the cavity but it is so big and deep the tree has been unable to seal the gap. The tree remains healthy and should live for another decade or two.” From the trees of Abney I learn that the material for our dearest metaphors are present already in the fabric of our lives.

Other things about Abney: the chapel is the oldest non-denominational church in Europe. The carved stone urns partly draped with veils. Extras of these piled beside a Simplyloo. The Egyptian style entry columns.

A long walk to the National Gallery, as the tube is unexpectedly expensive. I pass over canals, Kingsland graffiti, vertiginous mash-ups of architectural history and new construction. On Stoke Newington high-road, Arabic men drinking red coffee from tiny glass cups in front of bars and barbering establishments. Memorials displaced by bombs in the Barbican. Ornate underpasses. Smithfield wholesale market, whose sprawling industrial galleries are tastefully domed with glass and hinged with arcade glass. I have lunch at Fabrique. Ham sandwich on rye. Live flowers in glass milk jars on the tables. London Review of Books Cake Shop later on for afternoon refreshment. At last, two hours later, the National Gallery. A room full of still life floral arrangements, stray curves, diagonal axes. Closed peonies in shadow. I am an anachronist and miss in today’s world the understated ambition on display; again, the desire to contain all, the burgeoning thrust of the catalogue, the encyclopedia, the enlightenment era reach and grasp. The transparent wing of a dragonfly laid over a half-concealed leaf laid over a panted leaf on a vase. Palimpsest. My attention turns to the other museum visitors. A woman on a bench, having unconsciously adopted a Marian pose, arm over her backback, eye-shadow, Adidas, double rings on her wedding finger. Repose, in the gallery. Turner, Dido building Carthage: construction, development, empire, the empire of scope. The return again and again the judgement of Paris. This pairs well with my interest in Enlightenment era observational painting: anxiety regarding accuracy, discernment. Are these available to us? Is the illusion of possible accuracy even available anymore? I feel Cassandralike, intuiting a dark truth, completely bereft of a capacity to speak it or even explain it to myself. Agamemnon gets murdered off stage. What is mine is not knowledge but an inarticulate shriek in the shape of knowledge.

A beautiful painting by Meindert Hobbema called The Avenue at Middelharnis. Arbors, cranes in the backdrop, husbandry. Order (arrangement) and its derangement—that is, its warping. Hobbema excised two trees from the foreground of his painting to clear up the sky, giving it visual priority. You can see evidence of this on x-ray. Elsewhere: shipping scenes, ports, fleets. Trade and spectacle and confluence. Claude Lorrain, his lit backgrounds and shaded foregrounds: a curious sense of closure, lateness. Beautiful work by Beuckelaer: his four paintings make up a group illustrating the four elements: Earth, Air, Fire and Water. The elements communicated by way of market scenes as frame narratives for Christological imagery. Densely layered. The main event or subject as peripheral (in both cases). The Ambassadors. Again, epistemological ambition. Measurement, efficiency, death. Despite wayfinding technology: memento mori, pushed into the periphery to see the skewed skull rightwise. In many of these paintings of Christ and martyrs, the body is there to suppurate, gush, anoint.

At the end of the day, a long walk through St. James park and alongside Buckingham palace. Dinner on the steps of Westminster Cathedral, a beautiful striped, squarely Venetian building across from the malls near Victoria Station. The apartment buildings nearby match this decorative scheme. I listen to the nearby sounds of the wind in the maple, a roundabout with mopeds and bikers at its foot. Westminster has exquisite marbling on the interior, like being inside a shell discovered on a beach, creamy and lit from the outside in.

The next morning I call an Uber to get to Victoria station at 5 in the morning. The stillness and quietude of his Prius. I navigate to Gatwick and onto my first Easyjet to Lyon. I admire the Saint Expury TGV station for the structural integrity of its concrete arches and lattices. Once in the city, I take lunch at Ludovic B.—a restaurant about halfway through my walk toward Parc de la Tete d’Or. They’re confused at first but ultimately amenable when all I want is bread and cheese: with sweet balsamic reduction a demi Saint Marcellin, which has a pungent, good, bitter, indoors (interior?) taste. Again the sound of maple leaves beside a primary school as I leave the restaurant—refreshed, amorous for this place—and make my way toward my AirBnB beside the Rhône. At the park, where I linger until 2 pm, check in scheduled for 2:30, I walk through a fin-de-siecle wrought-iron greenhouse. Superheated. Camellias, the emblematic flower of romanticism, immortalized by Alexandre Dumas in his novel the Lady of the Camellias. Polynomial and Riemann equations graffitied in the public bathrooms.

I chat (in French!) with my AirBnB landlord while he finishes cleaning the place. He teaches literature at a university in Paris. We talk about my upcoming entrance at North Carolina and he points out that the study of American literature is one without any intertexts, so young and new as a literary epoch. The apartment is perfect. Windows with a rotting balcony overlooking the massive, wide celadon Rhône river. Multiple rooms to myself. Fourth floor. I leave to explore in the afternoon: the excruciatingly steep and winding upward staircases, the two hills of the city, old stonework built into the mountainside, the narrow pastel-colored riverside buildings wedged into each other. Stone reclining chairs by the waterfront, where I read for a while. A girl next to me is paging through Levinas in paperback. Saupers pompiers practice their diving in scuba gear in this summer heat. I wander through galleries and ateliers, trying to get a feel for the city, feel through its shirt to its skin to its spine. I follow signs toward Parc des Hauteurs. Ascend endlessly in 90 degree humidity. Like a pilgrim to a temple. Continued on into my misdirection, upward, plateauing, discovering the ancient Gallo-Roman theater ruins. Labyrinthine stone passages. Boys playing in their corridors. Sprays of summer flowers, purples and whites where grass springs between the ancient stones. Torpid bumblebees. A magnificent view of the city, its white buildings. Musicians practicing for the evening entertainment below, the drifting sound of saxophone, piano. Old heat of a late afternoon. I sit and read Faulkner and think on the vista and realize I may be experiencing a perfect and golden moment. Sometimes my ambling pays off. I buy bread and butter and a viennoise on my way home, dine in.

The next day—today—Lyon was less forthright with me. I started the morning at the mall, a dead hive experience, looking for a cheap t-shirt to get me through the day. I hadn’t planned for Europe’s heat wave. I went west, away from old town, until noon, and found Lyon in commercial merchant squalor. I walked through an indoor market, the smells of fresh fish, bread, doggish smell of hard sausage. Swallows all day, urgent cries overhead. Delighted by the high-pollarded avenues of trees I see from time to time—like the stilt legs of Dali’s surreal elephants. Into and out of cathedrals on my way: these are spectacular to look at, and each different in its own way (its own light), but curiously similar and banal, too. You tire after a while of vaults and stained glass. Women everywhere with hand fans—quaint. Back toward the river near 11 am. Shallow pools, a biker dragging through slowly them in rings, a wood boardwalk, strange metal plaques drilled onto 450 meters of the wood pontoon ramp. Research reveals it is an art installation by Philippe Favier called “J’aimerais tant voir Syracuse.” The wood ramp reminded Favier of an infinite “table d’orientation”—a semi-circular table you might find at an overlook or panorama. He came up with a series of literary terms for fantastic or fabulist places, inscribed these in metal plaques, and drilled them into the surface of the wood. Others, on their own accord, have added their own. La piscine du Rhône nearby, 60s style, space-needle architecture. Took a street lined with Arabic food shops and stores where you can buy traditional Muslim dress. The pastry-shops feature glittering caverns of tiny gem-like confections, glazed and square as ornate snuff-boxes. Purchased a pear tart for lunch and ate it in the courtyard of the old ESSM (École du service de santé des armées de Lyon-Bron). There, you can find a museum on the resistance and deportation. I wasn’t originally planning to visit, but I felt compelled, as I usually do when visiting France, to understand the complex European relationship with the second world war. Especially enlightening to learn that Lyon was included in Vichy France. Old propagandistic images of Petain. Narratives of racism, exclusion, turmoil. As if the shroud of Turin, a fragment of the parachute used by Jean Moulin to drop secretly into Southern France, where he was tasked by de Gaulle with uniting the resistance. An exhibit on the extensive food rationing in Vichy France. The ration stamps called “tickettose d’angoisse”—or “anxiety tickets,” for fear of losing them. Petain encouraged his populace to grow their own food. Steep increase of home gardens during the war years in places like Lyon. The countryside encouraged to donate excess to the cities.

Above all, the important lesson from the museum and today is how crucial the medical industry has been in Lyon. I get the impression there has been some kind of mandate to this end, and near the Grange Blanche later in the day I discover an austere statue of a robed woman with a sword and sheaves of wheat standing on a plinth that reads: “À la gloire du service santé,” which translates: to the glory of health services. The plinth features a frieze of figures at work nursing and ministering to the sick. At the Musée des Confluences, I encounter a “fermenteur Frenkel,” a large vat with clamps and dials used in the process of vaccine production. By way of prelude, the accompanying plaque informs me that Lyon has been backed by a long tradition of health and veterinary institutions, which led to this flourishing of the health industry in the 19th century. During the war, the ESSM was dismantled of its military status by Germany, but continued educating young men in the medical arts. Grange Blanche, which is near the Lumiere institute (more on this in a moment), is a veritable etoile of specialized hospitals.

Another industry central to the development of Lyon is silk production. My plan is to dedicate today to learning more about Lyon’s canuts, or silk-weavers. At the Musée des Confluences, I see large taxidermy displays that catalogue the components of the industry: large white braids; fat, gold-translucent moths; cocoons in various stages of unraveling. Also at the Confluences, which is where I go after the Centre, I also see a fiberoptic wedding dress, fringed with light, woven using Brochier technologies, which have been adapted from the original Jacquard loom types. The dress making technique was designed for the Olivier Lapidus haute couture fashion show in 2000, and the present artifact was made in 2014 by Mongi Guibane. Jacquard loom technology was used to develop the punchcards that supported the development of the computer and film industry.

In all, the Musée des Confluences is astonishing, and often painful to look at. Its exhibits are dizzyingly ambitious in scope. Permanent exhibitions include: “Origins, stories of the world,” “Species, the web of life,” “Societies, the human theatre,” and “Eternities, visions of the beyond.” The attempt here is to track a story of the world—a dubious aspiration, given the rigid warping porosity of historiography. The methodology here for engendering an epistemic experience is completely indiscriminate, much like the old-fashioned, original museums or curiosity cabinets. Indeed, there is a temporary exhibit at Confluences regarding the acquisitive spirit—a display of cabinets, carnets, colonization, observation, exploration. The latter exhibit teaches me that museums of natural history in France were often the outgrowth of imperial activity in colony nations—a strategy for understanding, and thus subverting, containing local populations and epistemes. I am overwhelmed here. Nothing is stable. I can’t concentrate on anything I see. A vast display of varieties of microscopes, magnifying glasses. Equally vast the glassed-in case of beetles, butterflies, shells of all kinds. I am desperate to concentrate, to core down to the heart of one of these objects. My mind does not operate on the basis of this kind of expansivity. I am wrecked by the curatorial attempt here to encompass all the world and all of human understanding—a cross-sample that asks its visitors to ask themselves: is there a duty to remember? A good question. I remember thinking on my walk today back to the conversation I had with my landlord, Thierry. We assume that literature is intended to amuse, entertain, or educate. But I think we forget the preservationist function of the medium, too. To safeguard in language language itself, the means of transmission of human learning and love. I can think of no holier obligation. This doesn’t mean just writing—this means writing in a tradition. I am sick and tired of literary peers who have no regard for the acquisition of or immersion in tradition, since this is the most important task for any artist. What you have to make or say is only possible as it relates to a long history of expressive force.

At the end of one of its permanent exhibits, a plaque declares: “The objects and specimens preserved in the museum’s stores and show in this exhibition constitute our common heritage. They are inalienable—they cannot be assigned or sold.”

Objects of note at the Musée: a Volva volva shell—a false cowry—unwrapping like a lily bulb, or a twist of angelic candy; a simple microscope designed by Dutch astronomer and physicist Christian Huygens, high performance, easy to use, made and engraved by Jean de Pouilly for wealthy clients. The privatization of accuracy for amusement’s sake.

The museum was designed to look like a crystal and a cloud by Coop Himmelb(l)au, Austrian studio known for deconstrutivist architecture.

After the museum I walk out to the point of confluences, where the Rhone and Saone flow into. It was originally a trafficked port area. The point hosts a submerged rail track for offload. Concrete pillars indicate incoming ships to pass “Gauche” and “Droite” (left and right). Now the area is under heavy construction, a rebuilding phase intended to urbanize the area. The regional governmental seat is nearby. Construction of apartments and other highrises. A mall.

I do a crash course in public transit and leave for the Lumiere Institute, which I learned about in a temporary exhibit at the Confluences on the Lumiere brothers, pioneers of the cinema and film industry, and lifelong locals of Lyon. Developers of a special dry plate for making photographs in the late 19th century. The institute used to house a factory for manufacturing these, and the brothers created their first film by recording end-of-day closing-time at the factory doors, the workers squeezing out, back into the world of their lives. The brothers, as the museum points out, were dyed-in-the-wool industrialists. There is something tautological about the development of this new medium: their first film (and so the first cinema experience) is an outcome of photographic plate development at the Lumiere factory. Later this factory would be converted into a studio production space. Here, the subject of film is film’s production; then the film eventually colonizes and magnifies the industrial context that produced it. No wonder the Best Picture Oscar goes every year to a film about film.

Watching early Lumiere films, I get the sense that what the brothers sought was movement, sheer motion. Their narratives were simply frameworks or pretexts for acrobatics, destruction, rising dust, consequence.

I eat a raw ham sandwich with goat cheese and sun-dried tomatoes in a little margin of grass near Grange Blanche. Delicious and sweet. On my way home, I stop at Place Bellecour (featured in a Lumiere film, as well as the Centre on resistance and deportation), then walk home from the Hotel de Ville. Music in the streets. Solstice is always la Fete de la Musique in France. For the last three years, every 21st of June I have been in France, where the streets at night fill with discos and trumpeters and opera soloists.

0 notes

Text

Day 3

St. Paul’s, the Portland Vase, the Elgin Marbles. Out by 8 on a Sunday morning. Hot by the door, especially at the door. Walked through Dalston, down Kingsland High Street. Kingsland—old royal hunting territory? So far living off of a Werther’s Original and a “British” apple from a Sainsburys. A minaret. The Threepenny Opera—its facade and pediments: “Progress” and “More Light / More Power.” Moorgate—once gave access to the moor that stretched along the northern side of the city. During the Roman period, the Walbrook stream maintained the area’s drainage, but the City Wall, built in AD 200 interrupted natural drainage and caused the formation of a large marsh outside the Wall. A small gate built. 16th century attempts to drain the swamp. Lay it out in walks and avenues of trees. Ceremonial entrance constructed. Wall destroyed, gate destroyed. 1817. The banking district. Building corridors, false pillars, Doric, Corinthian, Double. Gothic screens, jamb statues. The pediment frieze of the Royal exchange with a headress of highrises, cranes bristling behind it. Scooped nautilus-like swerve through Tivoli corner: “The bank made this way through Tivoli corner for the Citizens of London, 1936.” Security cameras peering down through the oculus of the cut-corner.

St. Paul’s. Site once of St. Paul’s cross, “whereat amid such scenes of good and evil as make up human affairs the conscience of church and nation through five centuries found public utterance first record of it is in 1191 AD it was rebuilt by Bishop Kemp in 1449 and was finally removed by order of the long parliament in 1643 this cross was reerected in its present form under the will of HC Richards to recall and renew the ancient memories.” When does the public imagination turn toward the past, toward ancient memories? To reevaluate, reorient. We don’t need this function today, because there are no common values, and so nothing to erode or improve. There are no common reference points, no St. Paul’s crosses. Inside, a breathtaking exhibition by Gerry Judah, twin three-dimensional, jack-like crosses, memorials for war dead, encrusted as though sunken, ruined anchors, with the coral growth of time. Nelson in St. Paul’s. London’s predominant populace is the brave war dead—time’s beggars, they beg our glory and honor, but there is none of that to give, for they have been replaced by success and lifestyle. The deep present. The stream. I sit for part of a sung matins service. Combined adult and children’s choir, stalls lit with little orange lamps. To build a cathedral, in which a person’s highest thoughts are given space to rise and extend! Spatiality of worship, aspiring forms of attention. Such a profusion of material—of dark wood paneling, blue and gold domes, smooth marble, certain slants of light depending on the time of day from the clerestory. Look up in the dome and there is a contextless scene of sweeping robes, sails, transpiring between columns and archways painted to be there. Angels in the spandrels. Wandsmen and stewards.

To Fabrique bakery. Cardamom pastry and rye roll with butter, the butter served me in a celadon espresso cup. Read Thoreau and listened to the employees speak Swedish. Went to Skoob afterward, looking for Faulkner and Hardy. Picked up Absalom, Absalom (how do we comes to terms with what the blind savage event does to us? Quentin’s historical imagination: “He would abrupt (man-horse-demon) upon…drag house and formal gardens violently out of the soundless Nothing.”) Also purchased Lights out for the Territory by Iain Sinclair as a stopgap guide to London. Begins in the punk sludge of Dalston, where I’m living, late nineties—a hunt for the “‘open field’ of semiological excesses on the wall” / “There’s nothing tangible…to photograph; lifting his camera would be like trying to stuff fog into a bottle.” A book whose narrator is trying to work through his “thirst for texts” in and of an urban landscape…

Walking: allowing the fiction of an underlying pattern to reveal itself. So he says. And Thoreau looks for “sympathies” between the “color of the weather-painted house and that of the lake and sky,” a “pretended life…[that] builds a causeway to its objects, that sits on a bank looking over a bog, singing its desires.” Thoreau and I seek sympathy. Sinclair seeks it too, but calls it language, London talking to itself through texts, “the continuity of rage.” Any continuity is a form of sympathy. To recall and renew the ancient memories.

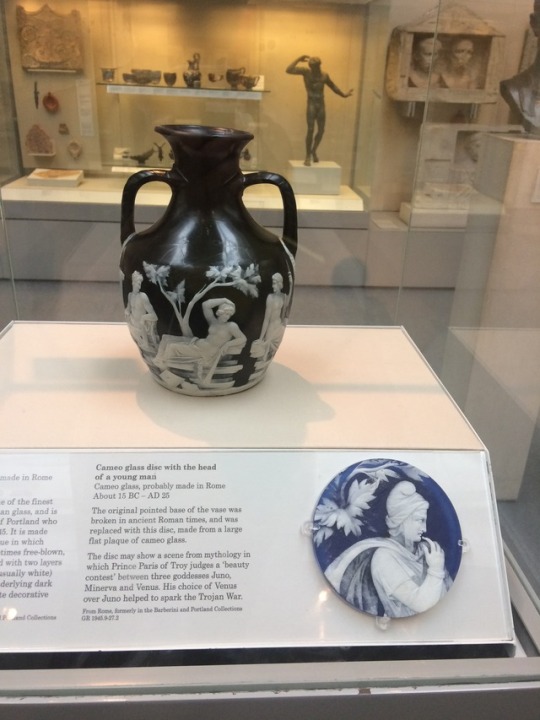

To the British Museum, sweltering inside on this hot day, up to the British landscape paintings—“places of mind” as the exhibit description calls them. “Relationship of parts cannot be analyzed / some inner design of very subtle purpose.” What is the purpose of a landscape, a relationship of parts, a linear pattern as a sense of place? Ravilious’s Wannock Dew Ponds, manmade hollows in South Downs. Patterns of hills, buildings, harbors reflected on port water gave Mackintosh the inspiration for his long, dark, slatted furniture forms. Whistler, Thames at Battersea, breathtaking grey wash where the direction of water staining renders a Thames waterline. Ruskin’s study of ivy—few better subjects to study than Ivy, says Ruskin. Nash noticing form in the seawall at Romney Marsh. Also: transport jars, amphorae for oil, wine, proof of trade in perishable goods between Cyprus and its neighbors. Excitement at locating another, different jar: the Portland Vase, which Keats looked at (inspiration for “Ode on a Grecian Urn”?): Roman cameo glass, soda-lime-silica, blue beneath white, the white then carved into, subtracted to produce fine shroud-like limbs of the marriage of Peleus and Thetis (some believe), abandoned mantles, seduction scene with a viper in the lap, mature peach trees subsiding to laurel. A black void is hidden underneath. We subtract to get at it, and our subtractions render us form, presence, figure. Subtract down to the plane of absence to offset presence; dimension and depth as sponsored by recession. Attritive progress: Faulkner’s wisteria. Paris and his judgement a replacement base for what once was a tapered base adorned with rural scenery. This latter replaced by the image of a young man choosing.

Nearly wept at the Elgin Marbles, while listening to Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring. Fragments of time and form, the pebble beach of our shared heritage. The pediments of the Parthenon. Demeter and Persephone. Hestia, goddess of the hearth. Though missing faces and heads, these figures are seemingly startled, disturbed by action we cannot see. Head and shoulders of the sun god Helios emerging with his chariot from the sea at dawn. Repose of the boy-figure of the river Ilissus.

Things to research further. Erasmus Darwin and Blake collaboration called The Botanic Garden, which features the Portland Vase. Why did Doubleday commission a water color of the fragments of the vase when it was broken by a drunkard in the 1840s?

A Tesco dinner of stale bread and dry couscous in the Russell Square park. Sitting rings of long-limbed pretty young people picnicking and making blithe conversation. What brings them here, with their red tennis shoes and bottles of wine?

1 note

·

View note

Text

Day 2

Air travel, Dalston, and the Thames. During my layover in JFK, I found myself lingering in front of a number of art exhibits in the terminal. Something surreal about encountering in a terminal, in front of a McDonalds, a bony ceramic work reminiscent of so many radiolarians called “History of Time,” comprised of 70 hand-sculpted segments. Indeed, in the hermetic environment of an airport, the scales of time and history seem wholly incongruous, asynchronous with those by which we measure ourselves on a day to day basis. An airport is a place made timeless and placeless, while still fully defined by spatio-temporal exigencies. I have heard airports called borderlands before. In today’s world, it feels wrong to call them that—that is, when there are so many true borderlands, true zones of subduction and blurred histories and identities, where people live out their lives.

I finished my new issue of the LRB and tear out a quote from Faulkner that Jameson makes in his article on Garcia Marquez:

“Once there was—Do you mark how the wisteria, sun-impacted on this wall here, distills and penetrates this room as though (light-unimpeded) by secret and attritive progress from mote to mote of obscurity’s myriad components? That is the substance of remembering—sense, sight, smell: the muscles with which we see and hear and feel—not mind, not thought: there is no such thing as memory: the brain recalls just what the muscles grope for: no more, no less: and its resultant sum is usually incorrect and false and worthy only of the name of dream.” (Absalom, Absalom)