Text

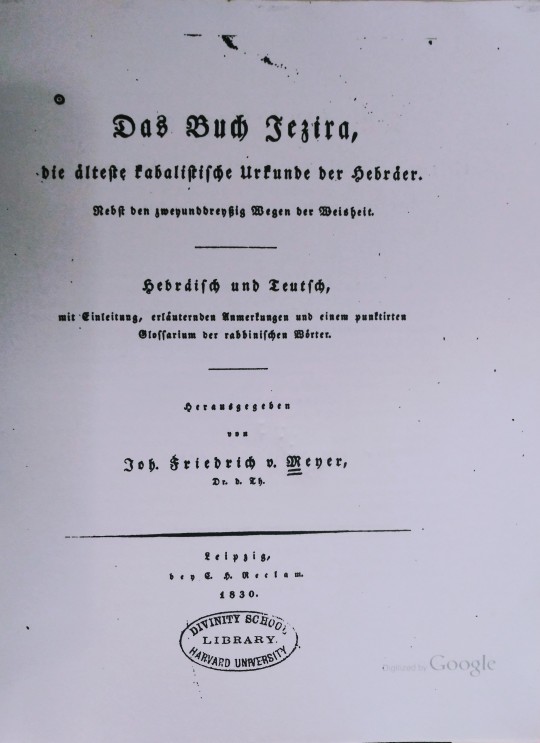

Das Buch Jezira, die älteste kabalistische Urkunde der Hebräer, Nebst den zweyunddreyßig Wegen der Weisheit. /Hebräisch und Teutsch, mit Einleitung, erläuternden Anmerkungen und einem punktirten Glossarium der rabbinischen Wörter. Herausgegen von Joh. Friedrich v. Meyer, Leipzig: C.H.Reclam, 1830.

[The Book (Sefer) Yetzirah, the Oldest Kabbalistic Document of the Hebrews, along with the Thirty-Two Paths of Wisdom./ Hebrew and German, with Introduction, Commentary, and Glossary of Rabbinical Terms by Joh. Friedrich Meyer, Leipzig: C. H. Reclam, 1830.]

This is the book that German philosopher G.W.F. Hegel mentions as forthcoming in his concise entry on "Kabbalah and Gnosticism" in his three-volume History of Philosophy (on this tumblr post below).

Meyer's translation of the Sefer Yetzirah was the first translation into a European vernacular language. Prior to 1830 it had only been known in Latin and Hebrew. ---SJT

******

The American, Isador Kalisch, whose translation of Sefer Yetzirah in 1877 was the first in English, translated the following paragraph from Meyer's 1830 German preface.

"This book is for two reasons highly important: in the first place, that the real Cabala, or mystical doctrine of the Jews, which must be carefully distinguished from its excrescences, is in close connection and perfect accord with the Old and New Testaments; and in the second place, that the knowledge of it is of great importance to the philosophical inquirers, and can not be put aside. Like a cloud permeated by beams of light which makes one infer that there is more light behind it, so do the contents of this book, enveloped in ob scurity, abound in coruscations of thought, reveal to the mind that there is a still more effulgent light lurking somewhere, and thus inviting us to a further contemplation and investigation, and at the same time demonstrating the danger of a superficial investigation, which is is so prevalent in modern times, rejecting that which can not be understood at first sight." ––Joh. Friedrich v. Meyer, 1830 (trans. Rabbi Isador Kalisch, –Studies in Ancient and Modern Judaism, New York, 1928, 345-346).

1 note

·

View note

Text

Hashish in Berlin:

An Introduction to Walter Benjamin's Uncompleted Work On Hashish

Paper read at the Walter Benjamin Congress, University of Amsterdam, 1997: Scott J. Thompson.

*****

O braungebackne Siegessäule

mit Winterzucker aus den Kindertagen [1]

This motto beginning Walter Benjamin's Berlin Childhood Around the Turn of the Century and appearing in a slightly altered form in Berliner Chronik has its origins in Benjamin's experiments with hashish, as Gershom Scholem and the editors of Benjamin's Gesammelte Schriften have noted. The "golden leading strings" [2] of childhood and the attempt to recapture their magic are interlaced throughout Benjamin's writings and experimental notes on hashish, opium and mescaline. As he expressed it in the mescaline protocol recorded by Dr. Fritz Fränkel in Paris on 22. May 1934, "The first experience the child has of the world is not that the adults are stronger, but rather that it cannot conjure."[3] In Benjamin's novella "Myslowitz - Braunschweig - Marseilles: Story of a Hashish Rausch" (1930), the narrator's hashish vision transforms a man in a restaurant into the image of a young boy in an Eastern European town. [4] In the essay "Hashish in Marseilles" (1932), a young boy on an electric tram is transformed into the sad child, Barnabus, from Kafka's The Castle. [5] In "Crock Notes" (1932), the opium smoker and hashish eater are said to "playfully exhaust those experiences of the ornament which childhood and fever made us capable of observing." [6] In the protocol to the hashish experiment with Gert and Egon Wissing in March 1930, Benjamin recorded the following:

I was not very attentive to what Egon said because my hearing immediately converted his words into the perception of colorful, metallic glitter which coalesced in patterns. I made this understandable to him by comparing it to the knitting patterns which we loved as the beautiful colored plates in Herzblättchens Zeitvertreib [Darling's Diversions] when we were children. [7]

In a more recreational experiment with the Wissings on 7. June 1930, Benjamin saw Gert transformed into "a slender boy in black attire." [8] When Egon Wissing supervised Benjamin's experiment with hashish and the opiate Eucodal on 7. March 1931, he noted that "toys or colorful children's pictures thrust themselves to the foreground again and again." [9] In the session of 18. April 1931, supervising doctor, Fritz Fränkel, noted Benjamin's extremely childlike sensitivity to color and wordplay, particularly his "remarkable number of diminutives." [10]

In his attempt to regain the child's magical power of conjuring by availing himself of Dr. Ernst Joël's invitation to become a test subject in a series of loosely monitored hashish experiments, Benjamin was able not only to independently evaluate the findings of Baudelaire's Artificial Paradise, which he told Ernst Schoen in 1919 would be required to appreciate the book, [11] but was also able to explore that root of his philosophical intentions, which Theodor W. Adorno has described as an ability "to render accessible by rational means that range of experience that announces itself in schizophrenia." [12] In his essay "A Portrait of Walter Benjamin," Adorno drew attention to the concept which unites the magic of childhood with "mental derangement," when he wrote that "The rebus is the model of [Benjamin's] philosophy." [13] The playful disorientation of the rebus and the delight in the sudden spark that ignites the mind with its solution are keys to Benjamin's concept of "profane illumination." Given Benjamin's mania for collecting children's books and books by the "mentally deranged," to which Scholem has attested in his essay "Walter Benjamin," [14] it is logical that he would have taken advantage of an opportunity to explore substances the experimental value of whose attendant rausch was described by his old acquaintances, Ernst Joël and Fritz Fränkel, in their article "Der Haschisch-Rausch" in the following manner:

Without proposing a blanket identification of spontaneous psychotic episodes with the phenomena observed in these experiments, we nonetheless maintain that an experimental way of penetrating abnormal states exists here, which allows us to investigate how far the individual can deviate from the norm, and to determine which psychotic symptoms in general are within the realm of the normal individual. The rausch provides a remarkable yield of sympathetic understanding for pathological symptoms (compulsion, schizoid behavior, delusions, incoherence, etc.). One acquires a new understanding for the mythic and the mystical. As for the alterations of particular qualities or the lack of such alteration, first we must identify the qualities in the norm, if the conditions of normal psychic processes are to be disclosed by pathological modification. [15]

Though they do not employ the term in their article, the concept of the psychotomimetic, a substance the ingestion of which is said to imitate or simulate a psychosis, supplies the operative paradigm in Joël and Fränkel's "experimental psychopathology," which they understood as both an attempt at "a total comprehension of altered psychic life" [16] and as a necessary corrective to the mechanistic psychopharmacology of Emil Kraepelin's school. It is important that we understand Joël and Fränkel's theoretical presuppositions if we are to bring an informed reading to Benjamin's experimental protocols and the extant writings which testify to what remains of that uncompleted book on hashish, once described by Benjamin in a letter to Scholem on 26. July 1932 as "ein höchst bedeutsames Buch" ["a truly significant book"]. [17]

In his pathbreaking book Du Hachich et de l'Alienation mentale [Hashish and Mental Illness] (1845), Jacques-Joseph Moreau (de Tours) [1804-1884], the doctor who introduced hashish to Charles Baudelaire and the Club des Haschischins, suggested that psychiatry could benefit by comparing hashish experiments with the symptoms of the mentally ill. [18] This idea was adopted by Emil Kraepelin (1855-1926), father of psychopharmacology, when he called rausch "Irresein im kleinen" ["derangement in miniature"]. [19] The Kraepelinian method however, according to Joël and Fränkel, failed to comprehend the entire human being, because it mechanistically severed partial functions of the psychic life, which were then altered by psychopharmaka and subjected to behavioristic testing. In this important respect, Jöel and Fränkel's critique of Kraepelin was related to Benjamin's critique of the Kantian concept of experience.

In his early treatise "On the Program of the Coming Philosophy" (1917), Benjamin had called into question the Kantian concept of experience based on Newtonian physics, describing it as "view of the world of the lowest order." [20] Against Kant's Enlightenment mythology, Benjamin offered anthropological and psychological evidence of alternative realities outside the Kantian purview.

We know of primitive peoples of the so-called preanimistic stage who identify themselves with sacred animals and plants and name themselves after them; we know of insane people who likewise identify themselves in part with objects of their perception...we know of sick people who relate the sensations of their bodies not to themselves but rather to other creatures, and of clairvoyants who at least claim to be able to feel the sensations of others as their own. [21]

The cognizing subject of Kantian philosophy was called "a type of insane consciousness." [22] Against the Enlightenment worldview of the Protestant burgher, Benjamin posited a coming philosophy which would reclaim the cosmic rausch possessed by the human being of antiquity. In his later essay "Surrealism: The Last Snapshot of the European Intelligentsia" (1929), this cosmic rausch and its materialist, anthropological "profane illumination" were to be appropriated by the proletariat in the coming seizure of power.

Some scholars have seized upon the Surrealism essay to downplay Benjamin's interest in psycho-pharmaca. The concept of "profane illumination" is stressed as an awakening from a rausch, which is all-too-often characterized as a "narcotic trance," [23] despite the fact that cannabis and mescaline are not narcotic. The "profane illumination" of the rebus, however, presupposes an initial disorientation and sense of being puzzled. The problem with taking Benjamin's Surrealism essay as a definitive statement on rausch is that in so doing we overlook the fact that most of Benjamin's hashish, opium and mescaline experiments were written after 1929. Protocols V - X were conducted between March 1930 and May 1934. In November 1930, "Myslowitz - Braunschweig - Marseilles" appeared in the journal Uhu. During the spring of 1932, the more theoretical Crock Notes were written in Ibiza, and in December 1932, "Hashish in Marseilles" appeared in the Frankfurter Zeitung. Then there are the passages on hashish in the Passagen-Werk. Nor may we forget that Benjamin had first told Scholem that "even my experiences while under the influence of the drug" were a "worthwhile supplement" to philosophical investigation. [24]

Other scholars, such as Gershom Scholem, Susan Buck-Morss, Sándor Radnóti, Norbert Bolz, [25] have been much less reticent to admit the extent of Benjamin's hashish investigations. In her Origin of Negative Dialectics (1977), Susan Buck-Morss went to far as to assert that:

...the insights induced by drugs were not insignificant to Benjamin's theoretical endeavors. His notion of the subject-object relationship which lay at the heart of his theory of knowledge bore the stamp of these sessions and characterized the particular nature of his empiricism. [26]

Despite these less reticent scholarly remarks about Benjamin and rausch, a book length study of these writings has not appeared, and although these writings have been available in German for twenty-five years, "Hashish in Marseilles" is the only work of this nature by Benjamin which is available in English. Were one to substitute "Benjamin" for "Baudelaire" and Über Haschisch for Flowers of Evil in the following passage from Benjamin's letter to Max Horkheimer [6. January 1938], one would discover an apt analogy to the status of these writings in Benjamin scholarship. Voicing his displeasure with what he perceived as their bourgeois limitations, Benjamin characterized the Baudelaire scholarship of his day in the following words:

The mark of Baudelaire commentaries is that, in all fundamental aspects, they could have been written the same way had Baudelaire never written Flowers of Evil. They are, in fact, challenged in their entirety by his theological writings, by his memorabilia, and above all by the chronique scandaleuse. The reason is that the limits of bourgeois thinking and even certain bourgeois ways of reacting would have had to be discarded - not in order to find pleasure in one or another of these poems, but specifically in order to feel at home in the Flowers of Evil. . . [27]

Having been able to feel "at home" in what remains of Walter Benjamin's uncompleted book on hashish, a new breed of Benjamin research-activists have begun to examine this material in depth. As Hermann Schweppenhäuser noted in his essay, "The Propadeutics of Profane Illumination," "like the micrological explorations that typify his philosophizing as a whole, [Benjamin's] experiences of rausch bring to light surprising finds." [28]

--Scott J. Thompson

San Francisco, July 1997

------------------------------------------------------------------------

Notes:

[All links to www.wbenjamin.org as The Walter Benjamin Research Syndicate have been inactive since 2016]

[1] "O brown-baked victory column with winter sugar from children's days" appears with the altered line "With children's sugar from the winter days" in Berlin Chronicle, trans. Edmund Jephcott in Reflections, NY, Harcourt, Brace, Jovanovich, 1978, p. 27. The original poem which was inspired by hashish appears in Über Haschisch, ed. Tillman Rexroth, Frankfurt a.M., Suhrkamp Verlag, 1972, p. 142: "Im berliner Nebel/ Gottheils Berliner Märchen:/ Oh braungebackne Siegessäule/ Mit Nebelzucker in den Wintertagen/ Französische Kanonen überragen/ Mein Fragen. /Barbarossa 1771" [In Berlin fog/ Gottheil's Berlin Fairy-tale/ Oh brown-baked victory column/ with frosted sugar in winter days/ above my questions spire/French cannon fire," in On Hashish, trans. S. Thompson, San Francisco, 1996, p. 105 <http://www.wbenjamin.org/translations.html>Cf. Gershom Scholem's afterword to Berliner Chronik, Frankfurt a.M., 1970, p. 132, cited in GS IV/2:973 and GS VI:798.

[2] Friedrich Hölderin, "Dichtermut" [Poet's Courage] and "Blödigkeit" [Timidity], cf. Walter Benjamin, Selected Writings, Vol. I: 1913 - 1926, ed. Marcus Bullock & Michael W. Jennings, Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard Univ. Press, 1996, pp.21-22; GS II/1: 105-126.

[3] On Hashish,op. cit., p. 91; Über Haschisch, op. cit. p. 130; GS VI: 608.

[4] GS IV/2:729-737; 1075; cf. also Über Haschisch, op. cit., pp. 41-42; On Hashish, op.cit., p. 9; As the editors of the Gesammelte Schriften have pointed out, Benjamin borrowed this vision of the schoolboy in Myslowitz from Ernst Joël's hashish protocol of 11. May 1928. The boy in the vision was none other than Benjamin himself. Cf. GS VI: 577; Über Haschisch, pp. 90-91; On Hashish, pp. 50-51.

[5] GS IV/1:415; Über Haschisch, p. 53; On Hashish, p. 19.

[6] GS VI: 603, 824; Über Haschisch, p. 57; On Hashish, p. 22.

[7] GS VI:588; Über Haschisch, pp. 107; On Hashish,p. 66.

[8] GS VI:592; Über Haschisch, p. 112; On Hashish, p. 71.

[9] GS VI:593; Über Haschisch, p. 114; On Hashish, p. 73.

[10] GS VI:598; Über Haschisch, p. 122; On Hashish, p. 82.

[11] Benjamin, Briefe I, ed. G.Scholem & T.W.Adorno, Frankfurt a.M., Suhrkamp Verlag, 1978, p. 219; The Correspondence of Walter Benjamin, trans. M.R. & E.M. Jacobson, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1994, p. 148.

[12] Theodor W. Adorno, "Benjamin the Letter-Writer" in On Walter Benjamin, ed. Gary Smith, Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1991, p. 329.

[13] Theodor W. Adorno, "A Portrait of Walter Benjamin" in Prisms, trans. Samuel & Shierry Weber, Cambridge, Mass., MIT Press, 1967, p.230.

[14] Gershom Scholem, "Walter Benjamin" in On Jews and Judaism in Crisis, trans. W. Dannhauser, NY, Schocken, 1976, p. 175; cf. also Neue Rundschau , 76, Jahrgang, 1965, p.3.

[15] Ernst Joël & Fritz Fränkel, "The Hashish-Rausch: Contributions to an Experimental Psychopathology," trans. S.Thompson [Walter Benjamin Research Syndicate: <http://www.wbenjamin.org/contrib_1926.html>, San Francisco, 1997]; it originally appeared in Klinische Wochenschrift, 5:1707,1926. Benjamin opened "Hashish in Marseilles" with a long except from this article.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Walter Benjamin/Gershom Scholem, Briefwechsel,ed. G.Scholem, Frankfurt a.M., Suhrkamp Verlag, 1980, p. 23; Correspondence, op.cit., p. 396.

[18] Bo Holmstedt, "Historical Survey" in Ethnopharmacologic Search for Psychoactive Drugs, ed. D.H. Efron, B.Holmstedt & N.S. Kline,U.S. Dept. of Health,Education & Welfare, 1967, pp. 4-9.

[19] E.Joël & F.Fränkel, op.cit.

[20] Walter Benjamin, "On the Program of the Coming Philosophy" in Benjamin: Philosophy, Aesthetics, History, ed. Gary Smith, Chicago, Univ. of Chicago Press, 1989, p.2; GS II/1:159.

[21] Ibid., p. 4; GS II/1:161-162.

[22] Ibid., p.5; GS II/1:162.

[23] Cf. Peter Demetz, "Introduction" to Reflections, trans. E.Jephcott, NY, Harcourt,Brace, Jovanovich, 1978, pp. xx, xxxi; Herman Schweppenhäuser, "Propadeutics of Profane Illumination," trans. L.Spencer, S.Jost, & G.Smith in On Walter Benjamin, op.cit., pp. 35-36; Richard Sieburth's interpretation of profane illumination in "Benjamin the Scrivener" [in Benjamin: Philosophy, Aesthetics, History,op.cit., p. 18] would divorce it from its propadeutics altogether, characterizing altered consciousness as "private avant-garde narcosis." John McCole [Walter Benjamin and the Antinomies of Tradition, Ithaka, NY, Cornell University Press, 1993, pp. 225-227] expatiates on Benjamin's accusations that the surrealists had an "entirely undialectical conception of intoxication" and not surprisingly find little value in "narcotic ecstacies." The list could be greatly expanded.

[24] Correspondence, op. cit., p. 323.

[25] See "Walter Benjamin's Hashish Experimentation: Remarks from Selected Secondary Sources," on the Walter Benjamin Research Syndicate website, op.cit.

[26] Susan Buck-Morss, The Origin of Negative Dialectics,New York, The Free Press, 1977, p. 126.

[27] Correspondence,op. cit., pp. 549-550.

[28] Hermann Schweppenhäuser, "Propadeutics of Profane Illumination," op. cit., p. 35.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

[Caption reads in English: “Forbidden bird.” Doodle drawn by Walter Benjamin during one of his drug experiments, some time between 1927 and 1934. From Walter Benjamin, Gesammelte Schriften, vol. 6 (Frankfurt a.M.: Suhrkamp Verlag, 1985, 617. ]

Included in REVERIE FOR RADICALS: Walter Benjamin and Experimental Psychopathology in the Weimar Republic, 1927 - 1933, by Scott J. Thompson.

************

Forthcoming: Regent Press, Berkeley, 2024.

https://www.regentpress.net/

____________________

0 notes

Photo

Front Cover of the 1st edition of Tales for Transformation, translated by Scott J. Thompson, San Francisco: City Lights Books, 1987. ISBN: 0-87286-211-9

Revised and expanded edition forthcoming from Regent Press, Berkeley, 2024.

__________

0 notes

Text

FROM ...HEGEL’S PHILOSOPHY OF HISTORY

Kabbalah and Gnosticism

[translation by Scott J. Thompson and online @https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/hegel/works/hp/hpkabala.htm]

Kabbalistic Philosophy and Gnostic theology are also occupied with the concepts of Philo. The first of these concepts is Being: abstract, unknown and nameless. The second is disclosure: the concrete which emanates from Being. The return to unity is also accepted to a certain extent, particularly with the Christian philosophers. This return, which is considered third, approaches Logos. [1] According to Philo, Wisdom [Sophia] is the teacher, High Priest, which leads the third back to the first, and thus to the vision (hóros) of God.

Kabbalistic Philosophy

Kabbalah is called the secret wisdom of the Jews. Much has been fabled concerning its origins, and much of it is enigmatic. It is said to be embodied in two books: the Sefer Yetzirah (Book of Formation) and the Sefer ha-Zohar (Book of Splendor). The Sefer Yetzirah is the same primary book which has been attributed to Rabbi Akiba. A completed edition is soon to appear from Herr von Meyer in Frankfurt. [2]

There are ideas in the book which lead into Philo to a certain extent, but they do so in a very enigmatic way, and are presented more for the Phantasie. It is not as venerably ancient as is claimed by those who revere it, for they suppose that Adam was given this heavenly book as a consolation for his fall. It is an astronomical, magical, medicinal, prophetic brew. An historical pursuit of its traces indicates that it was cultivated in Egypt.

Akiba was born soon after the destruction of Jerusalem. In 132 A.D. the Jews revolted against Hadrian with an army of 200,000 men. The Rabbis were also active in the revolt. Bar Kokhba had passed for the Messiah and was flayed alive.

The second book, Sefer ha-Zohar, is said to have originated from a pupil of Rabbi Simeon b. Yochai. He was called the Great Light, the Spark of Moses. Both Sefer Yetzirah and Sefer ha-Zohar were translated into Latin in the 17th Century. [3]

In the 15th Century a speculative Israelite, Rabbi Abraham Cohen Herrera, also wrote a book Puerto del Cielo (The Gate of Heaven) which is connected to Arab and Scholastic philosophy. [4] It is an enigmatic mixture, but the book does have foundations which are universal [allgemeine Grundlage]. The best within it travels along a conceptual path similar to Philo. There are certainly some genuinely interesting determinations of a fundamental nature [Grundbestimmungen] in these books, but they tend to lead to enigmatic fantasizing. In the early history of the Jews one finds nothing concerning the notion of God as Being of Light, or of an opposition between light and darkness (seen as a struggle between good and evil); one finds nothing in early Jewish history on good and evil angels, or of the rebellion of evil, its damnation and sojourn in hell; nor anything concerning the future world judgment over good and evil, and the corruption of the flesh. In these books of the Kabbalah the Jews first began to develop their thoughts about their reality and to unveil to themselves a spiritual, or at least spirit-world, whereas they had previously been absorbed in the mire and self-importance of their existence and in the preservation of their people and race.

Concerning the particulars of the Kabbalah, the following can be said here: the One is declared the principle of all things, for this is the primeval source of all numbers. Just as the totality of numbers is itself no number, in the same way God is the foundation of all things, Ain Sof (without limit). The emanations associated with Ain Sof proceed from this first cause through contraction of that original boundlessness; this is the hóros (boundary) of the first. In this first single cause everything is preserved eminenter, not formaliter but rather causaliter.

The second main point is Adam Kadmon, the first man, Keter, the first generated, highest crown, the Macrocosmos- Microcosmos, to which the emanated world is connected as the flux of light. Through further emanation the other spheres become the circles of the world, and this emanation is represented as a stream of light. Ten streams of light issue from the primal source, and these emanations, Sefirot, compose the pure world of Azilut (world of divine emanations), which is itself without variability; second, the world of Briah (world of creation), which is variable; third, the formed world of Yetzirah (the pure souls which are deposited in the material, the souls of the stars; the pure spirits are further differentiated as this enigmatic system proceeds); and fourth, the established world of Asiah (world of activation), which is the lowest vegetative and sentient world.

Gnostics

Fundamental notions similar to those of the Kabbalists constitute the determinations (Bestimmungen) of the Gnostic theology. Herr Prof. Neander has given us an erudite collection of the Gnostics, which he has explained in detail. Some of these forms accord with those discussed above.

One of the most outstanding Gnostics is Basilides. According to Basilides, the first is the unspeakable God, theós arretos, the Ain Sof of the Kabbalah, which as tó ón, o ón [Being] is nameless ('anonómastos), and immediate, as with Philo.

Second is noús (spirit, mind), the first born, Logos Sophía (Wisdom), the active dynamis (power) which differentiates more precisely into justice (dikaiosyne), and harmony (eiréne). These are followed by further developed principles which Basilides calls Archons, the heads of the spirit realms. A central issue in this schema is again the return, the soul's process of clarification, the economy of purification, oeconomía katharoeon, from the hyle (materia). The soul must return to Sophía and harmony. The primeval essence contains all perfection within itself, but only in potentia; the spirit (noús), which is the first born, is only the first manifestation of what is veiled, and created beings can only obtain true justice in harmony with it through connection to God.

The Gnostics, for example Markos, call the first the unthinkable, anennóetos, and even non-existence, anoúsios. It is that which proceeds into the determinate, monótes. They also call it the pure stillness, sigé (silence). From it proceed Ideas, angels and the aeons. These are the roots and seeds of the particular fulfillment: lógoi (words), rízai (roots), spérmata (seeds), plerómata (plenitudes), karpoí (fruit); and each aeon contains its own world within itself.

According to other Gnostics, for example Valentinus, the first principle is also called Aeon or the unfathomable, the primeval depth, the absolute abyss, bythos, in which everything is sublimated (aufgehoben) before the beginning (proárche) or before the Father (propátor). Aeon is the activator. The transition or unfolding of the One is diáthesis (arrangement), and this stage is also called the self-conceptualizing of the inconceivable (katálepsis toú akataléptou), which we have encountered in Stoic philosophy as katálepsis (grasping, conceiving). These concepts are the Aeons, the particular diáthesis, and the world of the Aeons is called the pléroma (plenitude). The second principle is called the hóros (boundary), the development of which is to be grasped in contraries, the two masculine and feminine principles. The one is the pléroma of the other, and the plerómata (plenitudes) emanate from their union, syzygía. The union is the foremost reality. Each opposite has its own integral complement, syzygos; the sum of these plerómata is the entire world of Aeons all together, the universal pléroma of the bythos (abyss, depth). The abyss is thus called Hermaphrodite, the masculine-feminine, arrenóthelys.

Ptolemaios attributes to the bythos two pairs (syzygous), two arrangements or dispositions (diátheseis) which are presumed through all existence: will and thought (thélema kaí énnoia). Colorful forms and ornamentation then enter into the picture. The essential determinate is the same: abyss and unveiling. The manifestation as a descent is also dóxa (splendor), Shekhinah of God, Sophía ouránios (heavenly wisdom), which refers to the vision of God (horasis toú theoú): dynámeis agénetoi (uncreated force), “the light about him flashes brilliantly” (ai péri autón oúsai lambrótaton phos apastráptousi), the Ideas, lógos, or pre-eminently the name of God (tó ónoma toú theoú), the name of the many-named God (polyónymos), the Demiurge, i.e., God's appearance. All of these forms pass into the enigmatic. In general, the fundamental terms of these different Gnostic theologies are the same, and at their core is an attempt to conceive and determine what is in and for itself. I have mentioned these particular forms in order to indicate their connection to the universal. Underlying this, however, is a deep need for concrete reason.

The Church repudiated Gnosticism because it remained in the universal, and grasped the Idea in the form of Imagination, which then opposed the actual self-consciousness of Christos in the flesh, Xpristós én sarkí. The Docetists say that Christos had merely an apparent body and an apparent life. The thought was a cryptic one. The Church stood firmly opposed to this in favor of a definite form of the personality, and it adhered to the principle of concrete reality.

******

Notes

1. Hegel is referring to the Neoplatonic triad of moné (Being or 'abiding'), próodos (the procession from the cause) and epistrophé (the return to the cause). - SJT

2. Das Buch Jezira, die älteste kabbalistische Urkunde der Hebräer (The Book Yetzirah, The Oldest Document of the Hebrews). Published by Johann Friedrich von Mayer, Leipzig, 1830.

3. Hegel is referring to the volume Liber Jezirah. Qui Abrahamo Patriarchae adscribitur, uno cum commentario Rabi Abraham Filii Dior super 32 Simitis Sapientiae a quibus liber Jezirah incipit. Translatus et Notis illustratus a Joanne Stephano Rittangelio. Amsterdami 1642. [For a more complete bibliography of Sefer Yetzirah, see Sefer Yetzirah Bibliography] - SJT

4. Regarding Herrera, Gershom Scholem writes the following in his encyclopaedic Kabbalah (1974): “Abraham Herrera, a pupil of Sarug who connected the teaching of his master with neoplatonic philosophy, wrote Puerto del Cielo, the only kabbalistic work originally written in Spanish, which came to the knowledge of many European scholars through its translations into Hebrew (1655) and partly into Latin (1684).” In another context Scholem mentions Herrera's rôle in the discussion of Spinoza and Kabbalah: “The question of whether, and to what degree, the Kabbalah leads to pantheistic conclusions has occupied many of its investigatior from the appearance in 1699 of J.G. Wachter's study Der Spinozismus im Judenthumb, attempting to show that the pantheistic system of Spinoza derived from kabbalistic sources, particularly from the writings of Abraham Herrera.”

In the context of Hegel's short entry on kabbalah, the following passage is worth quoting from Herrera's book Puerto del Cielo (included in a Latin translation in Christian Knorr von Rosenroth's Kabbala denudata: “Adam Kadmon proceeded from the Simple and the One, and to that extent he is Unity; but he also descended and fell into his own nature, and to that extent he is Two. And again he will return to the One, which he has in him, and to the Highest; and to that extent he is Three and Four” (Kabbala denudata I, Part 3, Porta coelorum, ch. 8, paragraph 3, p. 116). - SJT

––trans. Scott J. Thompson

0 notes

Photo

Joachim Sartorius, “Still Life With Basket of Glasses” in HÔTEL DES ÈTRANGERS, trans. by Scott J. Thompson, San Francisco: fmsbw press, 2021, p. 18.

54 notes

·

View notes

Photo

hans magnus enzensberger, “interrogating a vagrant” (”befragung eines landstürzers,” Suhrkamp, 1957), trans. by Scott J. Thompson, in FOUR BY TWO: Elsewheres: Scott J. Thompson/klipschutz, Summer 2015, (design by J.Gaulke), Smithburg MD, San Francisco, CA 2015.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

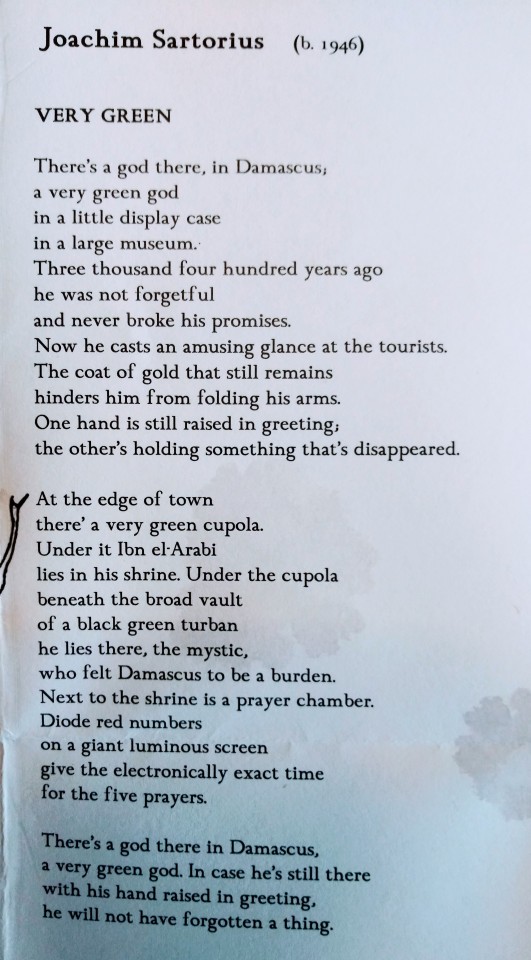

“Very Green” (”Sehr Grün”) by Joachim Sartorius, translated by Scott J. Thompson, from FOUR BY TWO: Elsewheres, Scott J. Thompson/klipschutz, Smithburg MD, San Francisco, CA, Summer 2015. Originally in HÔTEL des ÈTRANGERS, Köln: Kiepenheuer & Witsch, 2008.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

“Tortoise” by Syd Barrett, 1963. Reproduced in THE LYRICS OF SYD BARRETT, Foreword by Peter Jenner, Introduction by Rob Chapman, London: Omnibus Press, 2021, p. 18.

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The LYRICS OF SYD BARRETT, Omnibus Press 2021.

1 note

·

View note

Text

[Back cover quote: "Then --as though it could be used, as though it were for art -- I plant a grain of doubt

in your porous heart, and observe how everything that was small stretches out and everything else evaporates."]

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Joachim Sartorius, HOTEL DES ETRANGERS, Bilingual edition translated by Scott J. Thompson, San Francisco: fmsbw press, 2020. ( front cover) [Published on Jimi Hendrix's Birthday, Nov. 27]

1 note

·

View note

Photo

The Eight of Wands - Swiftness [Alacrity] – THOTH TAROT

Mercury in Sagittarius = The Quicksilver Messenger in the Archer’s House of Mutable Fire

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Coming back into print ON DEMAND – J.W. von Goethe, TALES FOR TRANSFORMATION [Alchemical Tales], trans. Scott J. Thompson, San Francisco: City Lights Books, 1988.

Photo above: The front cover of the 2nd edition

1 note

·

View note

Photo

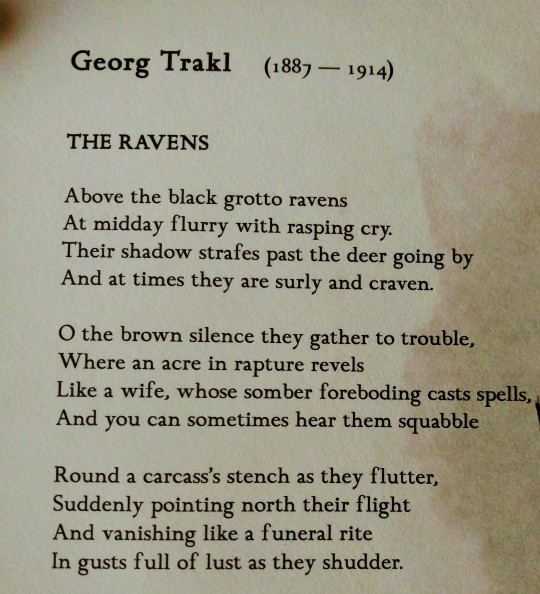

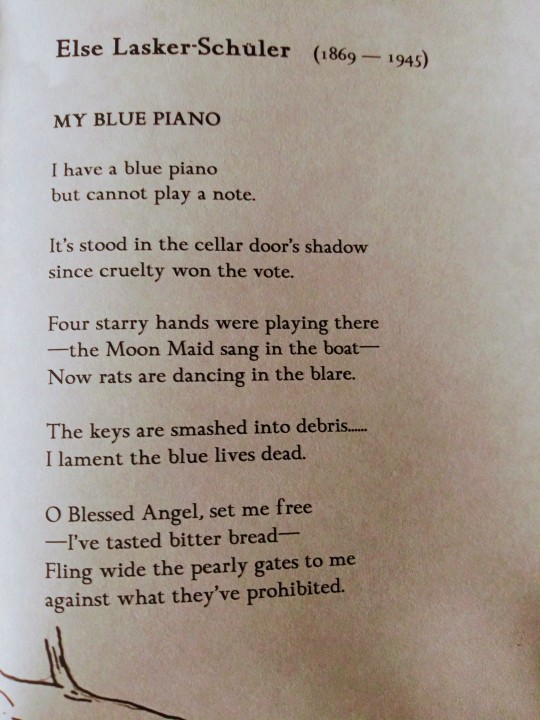

Georg Trakl: Sleep

[”My Blue Piano,” “The Ravens,” “Sleep,” trans. by Scott J. Thompson, FOUR BY TWO, Smithsburg, MD/ San Francisco CA, Summer 2015 – illustrations & design, Jeremy Gaulke

2 notes

·

View notes