Text

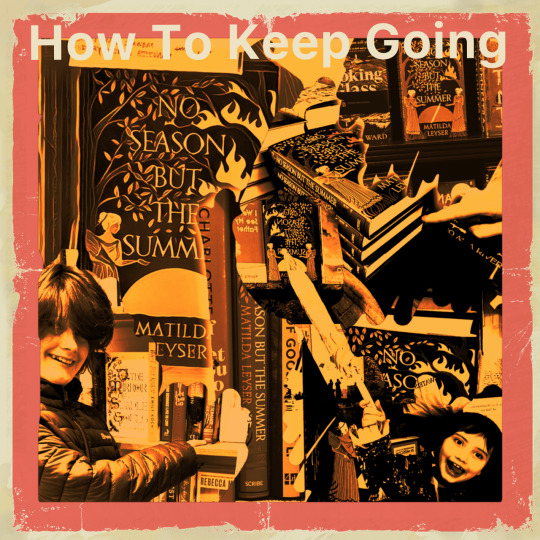

MY BLOG IS MOVING! and a blog on How to Keep Going, in the aftermath of anything

I have written 92 blogs, to date. I just counted, because I am slowly sifting and sorting through them, to transfer them over to my new website, which will house them from now on. 92 blogs, but today I feel wobbly about whether I can write this – the 93rd. It’s the first since I became an Author, published a book, and so, of course, as soon as I have this apparent entitlement granted – official legitimacy to write – I doubt that I deserve it or can do it. Proof, if ever I needed it, that self-doubt is a lifelong condition, and that however much acceptance I am given, or even accolades, I will still find a way to wriggle back out to the margins, to claim outsider status, because- truth be told – that uncomfortable place is where I feel most at home.

But there is another dynamic at play here as well, which is to do with finding myself an outsider, not only to the self-assured mainstream, but to my own work, which is out there now, in Waterstones. I can go in and buy it as if it had nothing to do with me (I did this yesterday) which in a way it doesn’t anymore. I spoke at the book launch of how much it felt like a boat launch – a goodbye party, as the boat-book sails off into the world without me, and I am meant to stand on the shore, to watch and see how it fares. But I don’t like the anxious checking – on Instagram, Amazon, Goodreads – the wait to see if it will get reviewed, make a long list, a short list, win a prize, whether it will ’make it’ at all. And I don’t like the sense of emptiness that follows this achievement – the almost inevitable anti-climax: ‘And now what?’

(My book in Waterstones)

So I stand, and hold onto my doubt – that old, uncomfortable, comfort blanket, and wonder whether or not I can write another blog. I wonder, in fact, if I can ever write anything good ever again. And this is also a familiar feeling. I recognise it of old – I just finished a novel dedicated to my mother, but this doubt reminds me of my dad.

My father suffered from a kind of creative hypochondria – as if he was always on the point of losing his powers. He was a German Jewish refugee who escaped to England in 1936, at 16, and was fortunate enough to find his way to Oxford University. An outsider who deeply valued his insider status – a mirror of me, in the next generation, an insider, who values her outsider-ness. He became a medieval historian, but not the dry and dusty kind- he prided himself on his prose, at the same time as being desperately offended once when someone alluded to his ‘purple passages,’ as if his work were all surface flourish. But whenever he finished a piece of work, he would worry as to whether he could ever produce another of equal merit. He published one book – Rule and Conflict in an Early Medieval Society – a scholarly work, never destined for the bestseller charts, but he’d check on its sales in the only way available to him, this being a pre-internet age: he would go into Blackwell’s and count the copies on the shelf. He studied, lectured, wrote for forty years, and worried for all forty of them as to whether he would lose it, or ever make it. When, at the age of sixty-four, he was given a professorship, he finally had at least one worry-free moment: “I’m it!” he told a colleague, by way of sharing the news. And, having become ‘it,’ he died a few years later.

(I don’t have many photos of my father - he is the one in the middle with the impressive eyebrows, that stayed black even when the rest of his hair turned grey)

It strikes me now, as I recognise the same angst at work in myself, as a very male kind of anxiety – ‘How did I do? Was I good enough? Will I be able to do it again?’ – as if each creative act were singular and climactic – a one shot deal – rather than cyclical and iterative. Which is all very well, to lean into these reassuring biological narratives, but I have just turned 49, and my biology and cycles are becoming increasingly irregular and unpredictable. So, I am wondering how to keep going, what other stories I can find to help me, and if there is a less exhausting, worrisome way to move on in the aftermath of publication.

It is both wonderful and difficult that, as a mum to two high needs children, neither of whom are currently at school, stopping is not an option. Motherhood is one long aftermath – which is surely part of the picture in post-natal depression. The birth – the great happening – is just the beginning. The rest of everything after, involves carrying on. Tonight, my daughter needed help to barter with the tooth fairy – can she keep her tooth and still get a silver coin? Can I write a note to ask? My son wanted support with emailing a video game company, keen to offer them feedback on their demo of Street Fighter 6 (good, but it’s too easy to spam the ranged moves, apparently). These things, and others – many much more gruelling than writing notes to fairies or reviews for games- must be done daily, nightly, and they have helped me develop a kind of ‘keeping going’ muscle, which, like the heart, simply keeps contracting, come what may.

On the whole, I am grateful that I have this stubborn reflex to keep going, keep writing, and that because of it, I have begun to learn two things, of which I need to remind myself now. The first is that it is worth accepting almost any commission – notes to tooth fairies, emails to game companies – I will take them, write them all. It is even worth writing rubbish, especially when I am feeling rubbish – depressed, scared, angry, ashamed – you name it, if I start writing it, then perhaps, one day, the good stuff may turn up. And the second thing is that the good stuff does turn up. It always turns up, eventually. It’s like on stage, when doing an improvised scene, you don’t need to make trouble happen – it will come and find you. Drama, story, just has a way of happening.

This law – stuff turns up, story happens – makes me think of my favourite kind of stall at the annual fair I went to as a child in Oxford. Every autumn the fair arrived. It transformed St. Giles, so that it took me until adulthood to recognise it as the street down which my father walked to buy croissants and coffee. Many of the rides frightened me, but I loved the stalls that were festooned with cheap toys – huge inflatable hammers, colourful teddies, bubble blowers – and which promised, in large, painted letters: ‘A Prize Every Time’. There were two kinds – one where you were given a long-handled butterfly net, and in the centre of the stall, a cloud of ping pong balls miraculously hovered. You only had to catch one ball to win a prize. And then there was the ‘hook a duck’ kind – a bamboo pole with a silver hook on the end, and a pond on a pedestal with yellow ducks, numbers on their sides, hooks in their heads, bobbing about, waiting to be lifted clear of the water.

I like the ordinariness of this image. The tackiness. The idea that the secret to creative resilience could be summed up with ping pong balls blown upwards, or rubber ducks drifting in a pretend pond. It gives me a certain steadiness in the face of this vulnerable post-publication time, and in our era of constant online showcasing, feedback, and never-ending worry. The prize may be a cheap plastic toy – not the Booker or any other literary wonder- but it is somehow lovely to know that you’ll get one every time. It helps me know that’s it’s not over. It helps me to move on from standing on the shore, looking out for a sighting of the book, like an anxious parent beside the carousel – to use another fairground image – waiting to spot my child on its next rotation. It helps me look beyond to the bigger picture of this merry-go-round earth.

So look, here I am, nearing the end of my 93rd blog, which I thought I couldn’t write. And, “Look,” I want to tell my father, “You needn’t worry – some works do well, others not so much, life happens, trouble shows up, the world as we know it may be ending – but story keeps unfolding. There is always another ping pong ball to catch, yellow duck to hook – a prize every time.”

And here are your questions – your prizes- to take away this month:

How do you keep going in the aftermath of something? It could be anything – a piece of work, but also a birthday, any point in the calendar to which you have been heading and then it’s over, and you hadn’t thought about this time, but now it’s here…..?

What keeps you steady? Gives you resilience? What are the prizes you can win every time, every day?

And if you want to keep reading these blogs – because I will keep writing them – stuff will turn up – please sign up to my mailing list on my new website, where they will live from now.

1 note

·

View note

Text

What’s Your Dreamhouse? Or What do you House in your Dreams?

'I should say: the house shelters day-dreaming, the house protects the dreamer, the house allows one to dream in peace.’ Gaston Bachelard

Our house is on sale. It says so on the post by the gate, that appeared overnight like some strange, thin, straight-trunked tree - a bright, new front garden growth, beside the blossoms.

We have only had two viewings so far. The estate agent said it would be better if we were out when he and the ‘viewers’ came round. I rushed about the house, putting away the clothes that are usually draped over the bed-ends, straightening pillows, laying a patterned cloth over an especially grubby section of carpet, hoovering, mopping, stacking the papers on the desk into a rectangle of order, making the house cleaner and tidier than it has been the whole time we have lived in it. I both dread it and take a perverse satisfaction in the artifice of it: it makes me think of putting on make-up (which I rarely do), or posting social media images that present us all as gorgeous (which I never do) - smiling kids, blue skies, neat lawns, lovely house, perfect life.

Because it’s all about the look, isn’t it? They are called ‘viewings’ after all. Not hearings - that’s a different procedure altogether. Not touchings. And yet of course those other senses come into play. Because we have done our share of ‘viewings’ ourselves, round properties that we might buy, and we don’t only look. We feel. The atmospheres of the different houses we have viewed have been extraordinarily potent. There were the ones on sale as the result of a separation - half the furniture gone, half still in place. The beds, not made in haste - left intact for weeks. A walk-in wardrobe, still full of a woman’s shoes. And then there were the ones on sale because the owner had died. Freezing cold rooms. A hole in the floorboards. A wonderful opportunity for renovation, the agent said. There was the one, too, that was brand, sparkling new - never been lived in - all gleaming glass, and a polished marble breakfast bar that hadn’t witnessed any breakfasts.

It is a very strange thing - to be shown around a stranger’s house, to let strangers look round ours, to consider selling, or buying the rooms through which we walk. It makes me think about the relationship between the house and the life that fills it, how intimate this is, how hard it is to separate them. I watch my daughter, playing on an iPad app that enables her to buy and furnish a new house for a family of rabbits, and I think of friends who indulge in ‘property porn,’ who go on Rightmove just for the hell of it, because they like to look at houses they will never buy. I think the attraction must be to do with this close relationship between the house and the life it holds, or how, as Bachelard puts it, ‘the house shelters day-dreaming,’ and so a new house invites a new dream. That’s the game, as we view houses: we have to try to look into the middle distance, past the soft furnishings, to dream into what it might be like to live there.

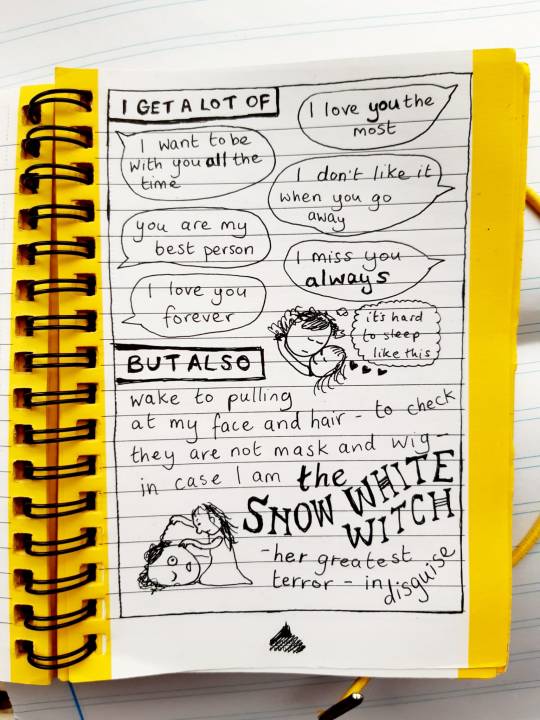

Meanwhile, my daughter is grappling, not with daydreams, but nightmares. She has a roof over her head. She lives a privileged, sheltered life. And yet she is terrified that the wolf might be at our door, or even in her bedroom. That she could be cut, maimed, or changed in some terrible, irreversible way. That a witch might come to take away her smile. Or worse. that I might be the witch or the wolf in disguise. She lies on top of me, the lights blazing at 3am because she can’t bear the dark, wide awake, quaking, raising her head to check on me, to check I haven’t transformed to reveal my true, awful identity. And no matter how many times I tell her she is safe, that neither I, nor any wolf, witch or other creature wants to harm, she feels terribly exposed.

Image by Zoe Gardner @limberdoodle

I don’t know if it is because we are moving that these fears have started to take hold of her with such intensity. I am sure it is part of it, but I think it is also the age she has reached, where she is struggling with the whole dichotomy of the real and the imagined, the house and the dreams within it. By day, she puzzles over whether unicorns are real. I am fascinated by her reasoning. She says they could be real but possess a potent magic that renders them invisible. But if this is the case, she is surprised the magic never wears off - why don’t we get an occasional glimpse of one? Or, even if their magic were infallible, why don’t we bump into them, and wonder what has hit us? Or might their magic be powerful enough to make them, not only invisible, but immaterial as well? In which case could we walk through them, without noticing? All those rooms, full of furniture, that walk-in wardrobe, full of shoes, could also house a unicorn. I love this. And she may be right - I mean, consider how many magical, mythical beings, with the power to be both unseen and untouchable, could flit about the world? But like the clunky, over-thinking adult that I am, I ask,“How about if unicorns are imaginary, but that imaginary things are as powerful as real things?” She doesn’t like this suggestion. And, while I might go on about the potency of dreams by day, at 3am when she is quaking, I too find myself falling back on the old: “It’s just a story. It isn’t real. There are no wild wolves in the UK,” - as if the wolf’s lack of reality were enough to undermine its status as a terrifying beast. As if denigrating the imagination could solve it. Ha. It doesn’t work - why do I keep repeating it?

I suppose because it’s everywhere. The idea of the real and its regal status, its unbelievable sense of entitlement - except we all believe it. Even when we know it’s fake. Even when we know the brochures of the houses are made to look glossy, and that a life in this or that property won’t simply, by association, be shiny with promise. We know how adverts work, but they still work on us. Everything asserts that the real and the imaginary are segregated, can be clearly differentiated, and at the same time everything relies on and uses/ abuses the fact (the hard fact) that actually their relationship is extraordinarily porous - that the two are threaded through and through each other, and through us, and that dreams are what reality relies on for its sovereignty.

So, what to do? How to navigate the houses, the viewings, the unicorns and the wolves? The outer walls, and the inner dreams, and horrors? I feel like I have been wrestling with this question ever since I was my daughter’s age and had my own night terrors. Mine were of worms in the bed - they might have softer mouths than wolves but they can still munch through you.

I think Mothers who Make has been one of my attempts to answer this troubling question. Because it takes two things that are pitted against each other and yet intimately linked - motherhood and making, care and creative practice, sheltering and dreaming - and attempts to explore how it might be to give them equal value and visibility. Is it possible to see the bright bedroom, and the invisible unicorns, and the imaginary wolves? And not to make them all the same - not to eradicate difference (that’s another MWM tenet) - but to recognise that they each have a valid, particular place in this world, and a profound effect on us, and that they fold back and into one another? A mother’s arms can be a solid place of shelter, a space to rest and dream, and at the same time the idea of ‘mother’ is a kind of dream too, which is part of why I could be a witch while I am in the role. I still remember the shocking moment of realising, once when she took her glasses off, that my mother was a real person who had a life, long before I was born, and was still, to some people, Henrietta, and not ‘Ma,’ which is what I used to call her - a name that itself came from a story book.

So I am not ‘just a mum.’ And the wolves are not ‘just make-believe.’ I think a dream can shelter you, and a house can haunt you. And when I prepare our house for the next viewing, tomorrow morning, although I will still make an effort to tidy up, I might deliberately ask a unicorn to stand, in full view, in the middle of our living room, which our prospective buyers may not see or feel, but they might sense her, pawing the carpet, adding real value to our property.

And you?

What’s the house of your dreams?

What are the dreams in your house?

Where do you find shelter? Inside which walls, or under what images? Within whose arms?

How do you view everything?

And can your viewing be far-reaching enough, close in enough, to see or sense the lot - the whole awe-full regal, real weave of it? The soft furnishings – life’s rich tapestry.

P.s. And if you want to buy our house, let me know. It’s very nice and it comes with a free unicorn.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

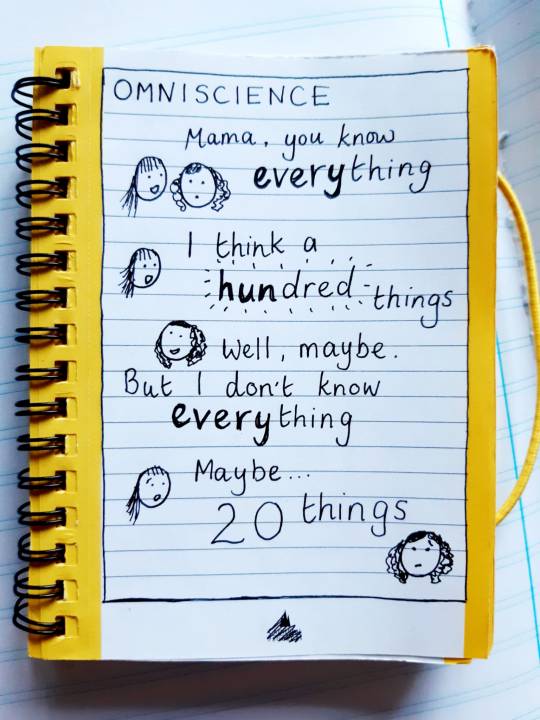

All the Things I Do Not Know

image by Zoe Gardner @limberdoodle

“I know that! You’ve told us that about a zillion times!”

This tends to be my son’s response to any information I relay. The literature instructs me that it is particularly important for neurodivergent children to have advanced warning as to what is going to happen in their days, but -

“I KNOW MUM! I do have ears!” is generally my son’s exasperated reply to my solicitous sharing of what he can expect of the day/ week/ year ahead. He is 11 but he says he has reached teenage-hood already, and duly rolls his eyes and groans, at how his mother never has anything of interest to say.

So, it came as rather of a shock to us both when, recently, it transpired that I had failed to tell him something of massive importance.

In the next six months we are aiming to move house. My son knows this - we’ve been talking about it for over a year. Plenty of build-up. He’s been positive about it. He’ll get his own bedroom - a space to store his precious collection of Nintendo and PS games. And last week we began looking at houses.

“Do you have a property to sell?” the estate agent who met us asked with a lip-sticked smile.

“Yes. Though we haven’t put it on the market yet,” I answered.

And my son, who does indeed have ears, heard.

Cut to, half an hour later, and we are stood on Oxted High street while he hurls abuse at me, accuses me of ruining his life, and of lying, because - here’s the nub of it - he hadn’t realised that in order to buy a house, we needed to sell our current one, and I hadn’t told him. I hadn’t told him because it never occurred to me, he didn’t know. But, from his point of view, that’s no excuse.

“I’m so sorry, love. I had no idea….”

“ ‘Sorry’ isn’t good enough! You think that little word is enough to make up for a whole year’s worth of lies!”

My son is very articulate, even, or especially, when triggered. A local shop-owner comes out to check if we are okay. I tell the concerned man we are, and go on listening to my son’s tirade, on the pavement, in the cold.

My daughter is the same. If I make a mistake, if I misinform her of anything - last time it was where I had stored her socks - I am a liar. No matter how many times I explain that lying is intentional and that I never intended to mislead my daughter as to the whereabouts of her socks, or deceive my son as to the ways of the property market, or hide from him our privileged but nonetheless limited budget, still from their point of view, if they didn’t get the correct information, then I have uttered falsehoods and deserve the full blast of their wrath.

For my children, both the sock and the house-selling incident are over. They have recovered and moved on. But, as is so often the case as an adult, like some slow, awkward giant, lumbering in their fleet-footed wake, I haven’t. Part of me is still standing on Oxted High St, hands in my pockets, head down, feeling the awful guilt and sadness of having failed to understand the extent of my knowledge and the limits of my son’s. I am still thinking it over, writing it down, figuring it out here with you.

Knowledge comes in so many different shapes and forms, and - as happened with me - you can stop knowing that you even know something, lose complete awareness of your privilege and power, and therefore fail to recognise the responsibility that comes with it. My daughter has begun asking ‘where babies come from’ - the facts of life- that knowledge to which, historically, culturally, so much weight is given. The fruit at the centre of the garden of Eden. It’s strange – there’s so much awkward self-consciousness around that particular branch of knowledge. And once you know, self-consciousness is meant to be the price you pay for knowing it. I’ve answered my daughter’s questions. She is only six, but I couldn’t see any reason to withhold the information. She didn’t seem too bothered. She thought it sounded rather gross and shrugged it off. No more self-conscious than before. But this recent experience with my son, of my not knowing what he didn’t know, has made me wonder what other kinds of knowledge I should wake up to owning and sharing - a different, more stringent kind of self-consciousness. What should I know to tell? What, if anything, should I consciously withhold?

The day before the Oxted High St incident, I submitted an application to do a practice-as-research PhD- a way, I hope, for me to write a second novel (the first comes out this April). In my application I had to relay what ‘gaps in knowledge’ my research proposal will address, or what ‘new contribution to knowledge’ I will make. As if there were an elaborate edifice of the stuff that humanity has been slowly building up for centuries, whose gaps must be adroitly plugged, and/ or whose turrets must be built yet higher, and higher until…..until I don’t know what. Until it all comes crashing down around us, which seems to me what is already happening, which is ironically why I feel a sense of urgency about writing another novel- not to contribute to our collective stash of know-how, but rather to open space for how much we don’t know, for how we haven’t got a clue. Which is also why, when the estate agent tells me, ‘The schools round here are wonderful,’ my heart sinks, my son scowls, because the whole education system, from key stage 1, through to PhDs, is based on stacking up knowledge, and I don’t see how my fiercely self-directed son will find a place in such a smugly knowing system.

As a creative, I am very comfortable with not-knowing. Even used to swaggering about it slightly, to highlighting its centrality in my PhD application. I work with Improbable. I married one of the artistic directors and had his kids. We are a company whose roots and core practice lie in improvisation, so ‘not-knowing’ is the gig, it’s the way everything and anything unfolds: listen; offer up, in the moment, what you know, acknowledging how hopelessly limited this is; let go of it; listen again. That’s the mantra. That’s the practice. But as I mull on this, and as I think back from art to life, and from the company to the kids, as I consider what I know, and what I tell, I arrive at a shocking truth.

You see, since my son accused me of lying to him for over a year, I have started making different kinds of lists in my head.

The list of the things I know I know. (Short)

The one of things I don’t know I know. (Indefinite - growing longer)

The one of things I don’t know I don’t know. (Completely blank, but infinite)

And then, the one that stops me in my tracks:

The one of things I know I don’t know.

The items on this list I do not tell. I try not to say out loud, even to myself. But now I have got this far I will have to name a few of them.

I know, I do not know:

When I will die and how.

When my children will die, and how.

If they will be happy before they do.

What the world will be like for them when they become young adults, in ten, in twenty years.

These things have come up. My son has told me - via WhatsApp, which he finds more comfortable as a way of sharing scary truths - that he is afraid of me dying, of anything happening to me or his dad, is worried he may never be happy. And I haven’t told him I don’t know the answers to his worries. Not when he is so close to panic anyway. Not when he is in tears. Not when he is, literally, throwing up with fear.

So I lie. I do what my mother did to me when I was little and I asked her the same. I pretend I know. For now. And I withhold, what seem to me to be the far more terrible, terrifying facts of life than where babies come from. It’s not how we arrive that’s hard to share. It’s how we leave, and what we might endure before we do- the things we do not know.

I cling, of course, to the first list - the shortest one - of the things I know I know:

That I love my son and daughter. That I always will. That I’ll do whatever I can to support them, which, mostly, doesn’t mean telling them what I know.

“I KNOW MUM!” is, as I said, the response I usually get if I do.

Because mostly the children do already know what I have to say. Or if they don’t, they will have a better time finding out for themselves anyway.

So, I think my job as a mother is, probably, after all the same as my Improbable one, the same as my approach to my creative work: to listen, to offer, in the moment, what I know, acknowledging how limited this is, and to continue to hold space for the awful, stunning, wondrous, unending list of things that I don’t know.

Hopefully, if I do that, the house-hunting will go a little smoother next weekend. But I’ll have to wait and see….

And in the meantime, here are your questions for the month:

What do you know to tell?

What do you withhold?

And how do you move around, work with, the things you cannot know?

You can answer as a mother or carer. You can answer as a maker or creative. And it is okay- more than okay – not to know.

3 notes

·

View notes

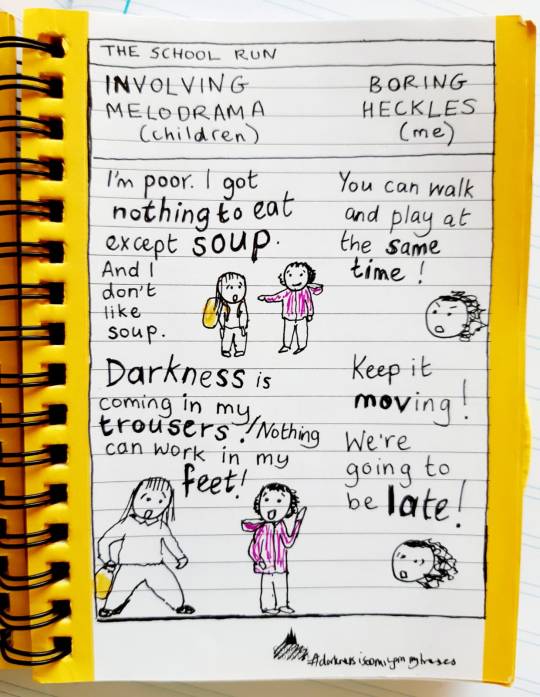

Text

LOOKING for CREATIVE COMPANIONS, MENTORS and PLAYMATES FOR OUR NEURODIVERGENT CHILDREN

What This Is:

This is a job notice, with a difference.

It’s different because it is for more than one job, so if you apply you get to say what kind of work you are interested in doing. You will, in part, be making up what the job is – it’ll be a collaboration.

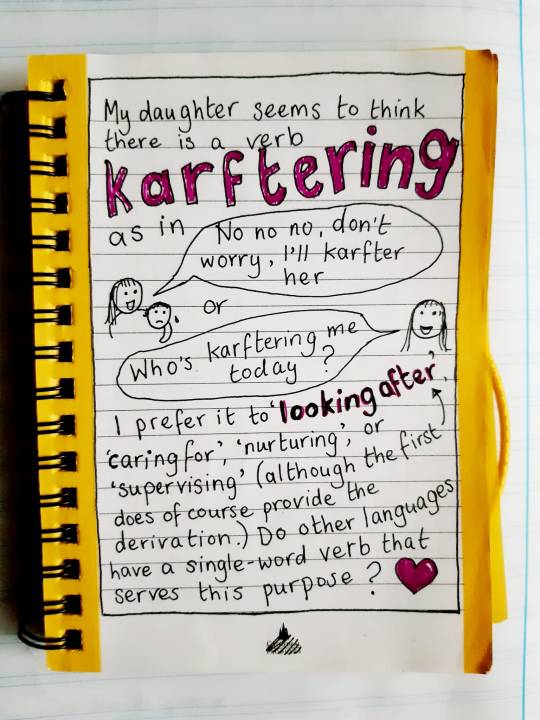

It’s different because I am trying to re-invent some language here – I don’t like the usual words used: childcare, babysitting, nannying, tutoring… I want to make some other words and ways. Maybe you can help me find them, or even better BE them.

The Situation:

We are a family of creatives – theatre-makers, writers, performers, artists, leaders, visionaries. We - that’s my husband Phelim McDermott and me, Matilda Leyser run Improbable and Mothers Who Make. We make theatre shows, operas, books, conversations, and other things happen in the world.

We have a 10 year old boy (nearly 11) and a six year old girl. Our son has a diagnosis of ‘high-functioning autism’, PDA and dysgraphia (the PDA means he hates being told what to do and the dysgraphia means he struggles with spelling and writing but is great at reading). Our daughter hasn’t earned any labels yet, but maybe one day she will. They are both fiercely creative, intense and challenging in all the best – and sometimes hardest - ways.

From January neither of our children will be at school. We will be based near Richmond in London, but at times traveling to Sussex and Kent. As a family we are in transition. We are trying to move towards Kent to found a creation centre there, and an alternative self-directed learning community. You can read about this project here: https://www.improbable.co.uk/the-gathering

While we do the work and research needed to move our vision forwards, to move houses, and to move our lives on, we are looking for a range of different people to come and engage with our children in diverse, creative ways, between January and July ’23 and possibly beyond…...

Our Children:

Here is some more about each of our children and what we, and they, are looking for:

Our son loves: gaming (platform games like Mario and fantasy RPGs); Dungeons and Dragons; Warhammer; comics; drawing; drama/ acting; jokes; pizza; farting; Lord of the Rings and Harry Potter.

He dislikes: being controlled or told what to do, or being persuaded to do something by a jolly, jaunty adult; boredom; noisy groups; nagging; spiders; chewy bits in meat; romantic bits in movies; racism; the Tories and environmental destruction. He wants to make a difference to the world.

For our son we are looking for: friends, especially people with whom he can chat about video games and the things he loves; a cool drawing teacher – he likes doing detailed pictures of fantasy characters; acting lessons; stage combat coach; someone who could teach him to touch type in a fun way; a teacher for video game-creation, coding and animation.

Our daughter loves: colours; hairdressing; costume design; fairies; magic; horses; cats; baking chocolate cakes; acting out and telling stories; singing and dancing; swimming; the rain; glitter and slime-making. She can also, she says, be quite tough.

She dislikes: being bossed about or told off; Steiner gnomes; boredom; when balloons fly away; being too hot; spiders; big dogs.

For her we are looking for: friends and play mates; artists to do messy and beautiful artwork/ making with her. She is also very keen on learning to read and write in a fun way and on doing maths. She wants to play at being at school, without having to be at school.

The Practical Stuff:

We are not necessarily expecting someone to be able to look after both children at once (I struggle with it, and I am their mum!). They have such different needs and interests at present, we are keen to meet each child where they are as far as possible.

The hours for these roles are flexible. The pay is to be negotiated, depending on what you are offering, but we’ll pay you properly. No particular previous experience is required – what is much more important is that you understand us and connect with us and our children. The only requirement is that you are DBS checked or willing to get a DBS check done.

So, if you are drawn to any of the roles or activities described above, please get in touch and tell me which and why. Please specify:

- Which child you want to support and how.

- Your availability and ideal hours of work.

- Two references.

Please write to me (Matilda) at: [email protected] by Dec 23rd st ‘22

If we are interested in meeting you, we will get back to you by January 8th at the latest to arrange a time for us to connect.

More Info:

You can read more about us and our situation through my blogs. Here are three which feel particularly relevant:

- On our vision for finding/ founding an arts-led learning community: https://www.improbable.co.uk/posts/the-gathering-what-nowa-call-for-more-cluesand-collaborators

- On the Problem with Childcare and a Lonely Hearts Letter for a Community: https://matildainmotion.tumblr.com/post/697097462606872576/the-problem-ofchildcare-and-a-lonely-hearts

- On Transitions: Help from Cookie the Chicken and a Hopi Elder. https://matildainmotion.tumblr.com/post/701894227217580032/transitions-helpfrom-cookie-the-chicken-and-a

0 notes

Text

TRANSITIONS: Help from Cookie the Chicken and a Hopi Elder

Mural on our living room wall by Tenar McDermott

Transitions.

One of those things that are meant to be famously hard for kids, especially for neurodiverse and/ or highly anxious ones, like mine happen to be.

And there are so damn many of them. The day - just an ordinary day - is full of hundreds of thresholds, little shifts and changes. Sleeping to waking. In bed to out. Night clothes to day clothes. Bedroom to bathroom. Upstairs to downstairs. Inside to out. Outside to in the car. Out the car to into school. And that list just covers up to 8.30am (and names my daughter’s least favourite transitions of the day). The other top three toughest transitions in our household, all of which can take hours and involve huge emotions, include:

Hungry to fed.

On screen to off screen.

Waking to sleeping.

And the strategies listed in all the parenting literature that are meant to help?

Routine. Strong predictable patterns.

To allow plenty of time.

To give early warnings. Count downs.

Music, songs, soundtracks …..

….which are all, I am sure, wise in many instances, but in our case don’t do much or can even escalate matters. Whenever I start giving my kids ‘early warnings’ they scowl at me and tell me to go away and shut up, because - let’s face it - I am just being the bringer of bad news. I am letting them know that change is coming. It’s on its way in half an hour. In fifteen minutes. In ten. In five. It’s nearly there. And if I then start to sing, or put on a soothing or upbeat soundtrack, that doesn’t help either. Not anymore. They know what I’m doing. I used to put on ‘Mah Nah Mah Nah’ from The Muppets in the mornings but they cottoned on. I might as well put on The Imperial March (Darth Vader’s entry tune – actually, I have tried this a few times), as all I am doing is letting them know that the thing they are dreading is nigh, and they don’t want to hear it. Who would?

I know I don’t want to hear it. Or rather I do - I want some kinds of change - I am longing for them, but not the sad, ending part. That part of the transition is horrible. And right now, everything in my life is in that phase:

I have just finished writing my novel. It’s over. And the next book has not yet begun.

We need to move house. I don’t yet know to where.

We need to move schools. I don’t yet know to which, or if we should start our own learning initiative.

My mother is recovering from pneumonia- the long phase in my life where she cared for me, and then helped with the children is shifting into the phase where I care for her.

The children aren’t little anymore, but they also aren’t big.

Oh, and I am peri-menopausal. Not yet an elder. But definitely not a younger now either - my years of a regular cycle are done.

Many endings then, but they are slow and messy. Sad and muddy. Like the weather. Not invigoratingly cold, or ablaze with tremendous autumnal hues. Not dying in style. But mild and wet. It’s pissing down as I write this and I might have to go out into the dark shortly to rescue the hens who have their coop perilously close to the river. My phone just buzzed with a flood warning.

My daughter wants to be inside the warm, dry cosiness of a new chapter already - to skip over the transition. She knows we need to move house, but she hates my mentioning it - she says it makes her too sad and she gets cross the moment the topic comes up. She wants to be already in the bit where the moving is done and she has a bedroom all of her own with pink, purple and gold painted walls, a bunk bed with a slide down from bed to floor and a cat basket in one corner for a kitten, called Sodie, who will be white, with a black spot over one eye.

Well, yes.

I’d like that too.

But even in Harry Potter (to which we are re-listening, over the bedtime threshold, courtesy of Stephen Fry) the transitions are hard. Disapparating (vanishing and reappearing elsewhere in an instant) is painful. Even when using magic, you can't avoid it - change hurts.

Especially when you don't yet know what you are going towards.

Especially when there is just the soggy, muddy, undignified ending part and the new thing, the next one, hasn't started yet. It's vague. An idea only. A fantasy. Or a complete unknown.

Rereading this I realise there are far more huge and terrifying transitions people undergo than the ones we are facing, couched as we are in a high degree of privilege. My father fled Nazi Germany at 16, having no idea what he was heading towards. Nowadays the number of people seeking refuge is only going up, with the water levels. Fleeing all they know. Going to towards everything they don’t.

But if inside every transition, however tiny, is hidden the same combination of sadness and fear - grief at what is being left, and terror of what is coming - I am not surprised my children howl and resist it with all their might.

What might help us? Since the official parenting tools I am meant to employ aren’t doing the job right now. Not in the tiny shifts, or in the big ones. And I feel downhearted. And scared. As the rain pours down outside.

So far, I have found two things that help:

Cookie the Chicken and a Hopi elder.

First, Cookie.

Cookie is not one of the hens out in the dark, currently at risk of drowning.

No. Cookie, lives in a little soft, pale blue hand-stitched pouch, on a pink thread. Cookie is there at the school gates to greet my daughter in the morning. If I manage to ease her from sleeping to waking, from in bed to out, from night clothes to day, from bedroom to bathroom, from upstairs to down, from inside to out, from outside to car…IF I make it as far as Cookie, waiting at the school gates, I know the rest of the transition will go just fine. My daughter will hop and skip over that final threshold into school, with Cookie by her side, or hanging round her neck, no backward glance.

Cookie comes to my daughter, care of one of the quiet hero’s of this chapter of our lives, who I will be very sad to leave when it does finally come to an end - the Wellbeing Lead at my children’s school. What I love about Cookie, (and the Wellbeing Lead) is that she is what I call ‘a threshold guardian.’ She does what all good threshold guardians do - she gets on with her own clucky business. She nibbles at chocolate chip cookies, sews seeds, and the other morning she even had a little chick, but she doesn’t bat an eyelid (if she had any), or drop a feather, in patronising concern for my daughter as she steps over the threshold. She doesn’t bring news of the doom of change, or promise glorious golden bedrooms or cute kittens to come. She is just there, at the point of transition.

I wrote a piece years ago called ‘Angels in Doorways’ which was about these threshold guardians. I wrote it at a time, long before parenthood, when I found it hard to leave the house. It helped me to think of these figures, stretched in the doorways like great webs, not doing very much, but making all the difference in the world. If you are old enough to remember him, the shopkeeper, of the magic costume shop in the children’s TV series Mr Benn is another example of just such a guardian: he’d quietly appear, beside Mr Benn, at his elbow, when it was time for the transition back to ordinary life. No warning. No countdowns. No soothing music. No questions. He was just there. Without fail.

So Cookie, who is there to help my daughter, also helps me. We all need a Cookie in our lives, I think. Pecking at biscuit crumbs, clucking in her little bag, while change comes.

And then there’s the Hopi elder…..

I’ve come across this quote a few times, and as I was listening to the rain outside, waiting for my son’s breathing to change to the slight rasp of sleep, wondering whether I need to head down the hill to rescue the actual hens, it came to mind again:

“There is a river flowing now very fast. It is so great and swift that there are those who will be afraid. They will try to hold on to the shore. They will feel they are being torn apart and will suffer greatly. Know the river has its destination. The elders say we must let go of the shore, push off into the middle of the river, keep our eyes open, and our heads above the water. And…see who is in there with you and celebrate. At this time in history, we are to take nothing personally, least of all ourselves.”

I find this oddly relieving. Terrifying, yes, but also relieving.

It is relieving that it contravenes the (perfectly sound, often untenable) parenting advice to sustain clear routines and rhythms, to respond to flux and change by trying to keep as much as possible stable and orderly. Because more and more I find myself wanting to do the opposite. To let myself and the kids break the rules, undo the rituals, eat on the sofa, draw on the walls, leave the dishes in the sink, stay up late, as if it were a special occasion, a carnival, a party. Sometimes I do these things, sometimes I don’t, but even acknowledging the impulse somehow helps me through the changing days. Actually, the one from this list that has most notably occurred of late is the drawing on the walls: what began, when we first moved in, as small illicit scribbles in a corner, done furtively by my daughter- then a toddler with a crayon- and which I vigorously expunged, has bloomed rapidly in recent months to become great figures meandering unchecked across the dining and living room walls. There are so many of these – all either girls or cats – that they do in fact look like a group in transit. They remind me of the graffiti on school desks – evidence that we were once here, and that we won’t be soon.

The Hopi’s advice also lifts me out of my small story, of books and houses and schools, and wakes me up to the fact that what I am experiencing isn’t actually personal - it’s a huge global shift. Transition is a condition of life, but it particularly describes the age through which we are living. I know the world is changing - can hear it in the hardness of the rain outside - I do not yet know how things will unfold. None of us do.

Every two hours, through the night, I get up and check on the government’s ‘flood alerts’ page - there is a graph of the river Medway’s water level near me. The black line shoots upwards at an alarming rate, reaching 1.36 metres at 1am but by 3am it has levelled off. The hens, for now, can stay tucked up in their coop.

And Cookie is there to meet my daughter in the morning.

All is well.

And much is ill.

My mother, convalescing, listening to Radio 4, tells me the news is bad.

No way round it. Change is coming. As the Hopi elder says, and as Michael Rosen tells us in We’re Going on a Bear Hunt,’ there’s no way round it. No way under it. No way over it. Got to go through it. So I will gather up the hens, the children, my mother, my husband, and push off from the shore, and along the way I am deeply thankful for the Cookies, the angels, the quiet shopkeepers of the magic costume shops, for accompanying us, across the threshold of this time.

How about you?

How do you weather the transitions, in your lives and in the world?

What are your strategies? Who keeps you company?

Or - to put it more prosaically - how the heck do get yourself, and the kids, out of bed in the morning?

Image by Zoe Gardner @limberdoodle

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Problem of Childcare and A Lonely Hearts Letter for a Community

Image by Zoe Gardner @limberdoodle

It’s taken me a long time to admit this, but- here goes: I have a childcare problem.

It’s like this: I am the primary carer for my two children. They are 6 and 10. My husband is away, working flat out between now and December. He is quite often away, quite often working flat out. My mother - the indomitable Granny - has been an incredible source of support and continues to do her best to help with the kids, but she is 81, currently very unwell and, much to her dismay, nowadays her iPad is often considered to be a more desirable companion than her. To make matters a little more challenging, school- that institution which serves as a reliable form of childcare for so many – has not been working out well for my son so he is now at home, full time. My daughter goes to school, rather reluctantly, but only for the mornings. Meanwhile, I have work to do: I have an initiative called Mothers Who Make to run; I have The Gathering to lead, which is a project with Improbable, to find the company a home, and found a new creation centre; I’ve one novel to get published, a second one I want to write, and there’s a couple of shows to be made too. So, all in all- sometimes - I could do with some support with the kids. Of late, Granny’s iPad, or my son’s Playstation - one screen or another - have become my fall back. I don’t see screens as the source of all evil, but I would like there to be other options, other people, in my children’s lives. As I said- I have to face it- I have a childcare problem. I also, however, have a problem with childcare.

Even the name irks me. The way it takes two things that have minimal status - children and care - and tacks them together, as if to tidy them away together in their own discreet corner, where they won’t bother anyone. But then that is, more or less, why the term was invented - to have a name for the special new corners where children would be kept while their parents worked. It’s a fairly recent invention. Although the task of looking after children is as old as the human race, the need to make the activity into an abstract noun, a thing, not attached to a person, like a parent, isn’t. In the UK, the first nursery was opened in 1816, for the children of cotton mill workers. And now, two hundred years on, what bothers me, is how it has become such a dominant term, how it tends to monopolise the conversation around what it is to be a parent who is doing other work, besides the full-on work of parenting. How a creche, or good childcare, is often identified as the golden answer that is going to solve everything, make our lives easier, our important work feasible, our flourishing ambitions attainable. As if, in short, the children are a problem to be solved, to be swept out the way, in as convenient and as affordable a way as possible, so that our path is clear once again, and we can proceed, to all intents and purposes, as if we had never had them. I am proud of the fact that my children continue to be a highly inconvenient presence in my life, day and night. I am grateful that they continue to trouble and disturb me. One of the first MWM’s blog I ever published, back in 2015, was about this - about how the conversation around childcare tends to corroborate the strong cultural trend that values professional work over and above the work of parenting, and that segregates the two, to ensure that, in the workplace at least, children are neither seen nor heard, and that even their parents are not heard referring to them.

I suppose I am grumpy about, and quietly resisting, the fact that childcare is necessary. I am grumpy about living in an industrial, capitalist, divisive, isolating culture where care is not a given, but where you have to pay other people to do it. And if you do it yourself, unpaid, you are ‘just’ being a mum, which is seen as a demeaning and boring task. On a certain level, paying someone to care seems like a contradiction in terms, because all the things that make care truly caring, rather than merely perfunctory, are things that, famously, money can’t buy - kindness, warmth, connection, love. Which is not to say that there are not some phenomenal people out there, who do truly care, working as childminders, in nurseries, and other settings. However, in paying for childcare we are, essentially, paying for someone to stand in for the friends and family that are, for many of us, sadly absent from our lives. We are forced to buy into a culture, that I would like to change - so, for the most part, owing to my grumpiness about the need for it, I haven’t used any childcare. I have stubbornly avoided it. I am well aware that my stubbornness is, in itself, a privilege - most people simply have no choice. But I have been able to bring my children with me to work and/ or rely on the one family member who is around - Granny - and/ or rely on screens. Which is all very well - wonderfully high-minded of me - but the fact is that, sometimes, I don’t have anyone to look after the kids.

I have made a few, rather feeble attempts to address this problem over the years. When my son was much younger, once or twice I tried to find and pay someone to help, but things didn’t go too well. One time my son ran away from the very lovely person who was meant to be looking after him, and on another occasion, with a different lovely person, the relationship ended with my son point-blank refusing to speak to them. I tried a little nursery for a term but he never settled. He managed a creche for a whole ten minutes once - I found him hiding in the toilets, when I hurried back to pick him up. This was before my son had earned the title of ‘neurodiverse,’ and so the world saw him as simply extra-inconvenient. None of this helped in shifting my sullen attitude towards the issue of childcare. But there was one hopeful thing: I remember I was inspired by the brilliant, and radical approach of another creative carer, P Burton Morgan, director of Metta Theatre, who drew directly on their community of actors and other creatives within their circle, to hang out with their son when they needed support. I too tried to grow a small group of friends and colleagues around my son, which worked to a point, but I never got very far with it. And then my daughter came along, and we moved out of London, and all my efforts to find some other support with the kids fizzled out. However, I think it might be time for me to have another go, to see if there is a way both to solve my childcare problem and my problem with childcare. I am wondering if I can re-invent some of the language and processes around it. I think, rather than advertising for a childminder, or a nanny, or going to an agency to see what I can find, I want to write a lonely hearts ad, because, in essence, that’s the problem. That’s all of our problem - the village or community around us, that isn’t there. In essence, my children and I are lonely.

I’m going to try it right now - My Lonely Hearts Ad. Here it is (written in collaboration with the children):

Creative, eccentric, neurodiverse family seeks support and community, specifically……

Boy, aged 10, likes Dungeons and Dragons; Warhammer; fantasy RPG video games; comics; drawing; drama; jokes; pizza; farting; Lord of the Rings and Harry Potter.

Dislikes being controlled; boredom; noisy groups; nagging; spiders; chewy bits in meat; romantic bits in movies; the Tories and environmental destruction.

Seeks friends; people to play games with; a cool drawing teacher; acting lessons; stage combat coach, and a teacher for video game-creation.

Girl, aged 6, likes horses; being happy; colours, clothes; toys, baking marble cakes; a good tree to climb; playing ‘abandoned kitty’ and ‘cat and dog;’ bath bombs; swimming; the rain; glitter; magic, and Harry Potter.

Dislikes being bossed about, or told off; gnomes; boredom; when balloons fly away; being too hot; big dogs.

Seeks a horse-riding teacher, a kitty; a horse and a chihuahua.

Woman, aged 48, likes her husband; her children; writing; dancing to hit songs that her kids have outgrown; big questions; myths; poems; bookshops; certain kinds of theatre; trees; heights; wild swimming.

Dislikes horror movies, even slightly scary movies; losing notebooks; the YouTube videos of people doing game talk-throughs that her children love; other kinds of theatre; housework; peri-menopausal fatigue; the idea of childcare.

Seeks creative friends, mentors, and/ or teachers for her children; an amazing cleaner; a deeply trustworthy and wise doctor/ healthcare practitioner; collaborators to set up an alternative arts-led learning community in Kent.

(N.B. In the same family, there is also: a man, aged 59, likes theatre, dislikes working as hard as he is, seeking some time off. And a granny, aged 81, likes her grandchildren, red wine, radio, dislikes yappy dogs, being cold, uncertainty, seeking some stability. As I write this the man is at work and the granny is in bed, so I couldn’t consult them about the full contents of their lonely hearts ad.)

If you think you might be the one, or one of the ones, or know one of the ones, we are seeking, please get in touch. You can post below or write to: [email protected]

You can also respond to this by sharing your own family lonely hearts ad, your own notice of need. Together we could start a childcare revolution - not a new idea, but rather a slow recreation of a very old one- a community of care.

0 notes

Text

My Haunted Housewife and Your Summer Commission

Image by Zoe Gardner @limberdoodle

As a child, I was good friends with a boy who lived further down our street. He used to come round and try on dresses from our dressing up box. I was a tom boy, so I donned the dresses less than he did. Despite the fluid gender play this suggests, one day my four-year-old boyfriend, told me that he wanted to marry me, but there was one condition: I mustn’t keep house like my mother. His house was immaculate. Ours was not. I declined his proposal. However, the man I did marry would, to be honest, also be quite glad if my house-keeping style were less like my mother’s.

My mother is an amazing woman, and an invaluable Granny, with many incredible qualities, but a sense of order isn’t one of them. She was once stopped for speeding, and when the policeman asked her what she did for a living, my mother replied that she was a housewife, at which my sister, from the back seat, piped up ‘You’re not a housewife!’ Apparently, like my first boyfriend, in my sister’s estimation, my mother didn’t do enough of the things that housewives are supposed to do to qualify for the role.

A housewife. I also feel I don’t qualify for the role and am not sure I want to. But I have chosen to be the full-time carer for both my children and am able to do this because my husband supports us financially. So there have been many times, over the last decade, when my husband has been out at work and I have been back home with the kids, in the house. If asked by a policeman, or anyone else, I would never describe myself as a housewife – nor would my husband - but somehow the title haunts me still. I find it uncomfortable. So uncomfortable in fact that, four years ago, I rearranged our lives to escape the ghost of it altogether: the children and I moved out, to live with my mother. My husband and I became separate but not separated. I retained the title of ‘wife’ whilst leaving the house. Wife-in-another-house, felt easier than being a haunted housewife. There were other factors involved in the move as well - a school for our ND boy, and a new place for my mother to live, after she had made the courageous decision to pack up the ramshackle house in which we all grew up- but my fear of housewifery was certainly part of the mix.

What is interesting is that in making the move, I did not escape any of the labour of housekeeping - the tidying, cleaning, cooking, caring - the only change was in my status, or my idea of it. I feel this forcibly right now, because this summer, for the next few weeks, I am again sharing a house with my husband. We are in Stratford Upon Avon where he is directing a huge show with the RSC- My Neighbour Totoro, which tells the story of a father and his children moving into an old, haunted house in need of cleaning, while the wife is away in hospital. Today, so far, in the lovely and spotless house, with cream-coloured carpets, the RSC have lent us, I have folded clothes, put on the next wash, unloaded the dishwasher, carried out the rubbish, made breakfast, written the day’s shopping list, while my husband has been out in rehearsals. I want, in the long term, to live under the same roof as him again – being separate but not separated has been hard, and painful - so it’s time, I think, I faced my housewife-ghost, time I stayed put in the house, instead of running from it.

Housewife. What’s my problem, really? Put some good music on, and the cleaning/ tidying/ cooking are fine. Not my forte, but I can get into the groove and can appreciate the results of cleared space, of a greater sense of order. I read The Invisible Actor when I was young and single, and I still like Yoshi Oida’s proposition that sweeping, clearing and caring for a space is a vital part of a creative practice. But somehow, as soon as these practices are placed in relationship to a husband, who is outside the house, in the world, doing creative work that is paid, that pays in fact for the house itself, some part of me freezes, fights, or runs screaming. Oh, and there is the childcare too - the main job which my mother did do, which I do too, but which is somehow invisibilized within the term ‘housewife’ as if it were more important to look after the house than the children within it. Or does the term not describe the work done, the care taken, at all, so much as merely the location of the role - a wife inside a house?

I decided to look up the history of the word.

I discovered that ‘wyf’ in Old English, meant woman, but not necessarily wife, while ‘hus’ was a dwelling or shelter. So, in its origins, the term means ‘a sheltering woman’ - a woman in charge of a dwelling, not one trapped within it. It actually describes a leadership role. I read further.....

“Originally, hussy was a shortening of the Middle English husewif, "housewife." Through the 1500's, hussy came to mean "any woman or girl," and by the 1650's it meant "an improper woman or girl.”

(from https://www.vocabulary.com/dictionary)

From this I understand, at last, what haunts me. It’s because of this slippage in meaning, the way the same root word for a woman, can slide and take on opposing connotations. It’s because alongside the current, modern usage of the word ‘housewife,’ which has narrowed to mean, not any woman, but a wife- a respectable, tidy, proper one, inside a property - there is the ghost of this other meaning, other woman, the improper one, the loose, dirty hussy. Behind my haunted feeling, is the hidden sense that if I don’t do a good enough job at the tidying, I too will have slipped, have sullied myself, and even that I could then be in danger of losing my house, place, shelter. Because, as my four-year-old boyfriend already understood, how I keep house is, or was, in some way, a reflection on the kind of woman I am - proper or not. (Incidentally, he grew up to become a lawyer, who helped my mother sell her untidy house).

But this slippage of sense is an invitation, as much as it is a trap. It reminds me how much meanings can change, how none of these roles are as fixed as I imagine them to be. I know this. I know that sense and status are not set but shift constantly. Like housework, they are never done, never over. They are a process - in motion. And since I am not, in truth, that great at cleaning, I am never going to get rid of the ghost of the huswyf/ hussy by dusting. I cannot mop or wash my way towards agency. No, the thing that will make it possible for me to reclaim or re-make new meanings, in the house, in the world, as a wife, woman, hussy, mother, is making - making stuff, having a creative practice, which at the moment, for me, is writing. So, as well as unloading the dishwasher and folding up clothes, this morning I have also sat down and written this.

This is essential work. It is unpaid but it is not a luxury. Making is a privilege but only in the same way that having enough food is a privilege, having water (let alone a dishwasher!), having a shelter - it is a fundamental privilege. I think again of when I went on Woman’s Hour to talk about Mothers Who Make exactly four years ago- just when I was fleeing the ghost of the housewife role in fact - and of that final, fatal question which Jenny Murray posed: “But do any of you actually make a living from your making?”

I felt the need, in the moment, to be polite - to acknowledge the very great privilege of being supported by my husband - and then regretted it at once. I mean, I said that, on Woman’s Hour?! On Wyf Hour?! On the programme to which, I imagine, women up and down the country listen as they unload their dishwashers. I wrote a blog immediately about what I wish I’d said instead, about how I wish I had questioned the question. Four years on, I am still answering Jenny Murray in my head, and my reply has grown, if anything, more vehement: “No!” I say, “I’m not making a living, not making any ends meet. But this does not mean my making matters less. Because I am a huswyf. A shelter-woman. I am sheltering lives and stories. I am making meanings meet. I am house-keeping - keeping the house safe for all it holds. And although this work is unpaid, it is, at least in part, up to me, and up to you, Jenny Murray, what status it is given.”

When I first got funding- the first time I was paid to make anything - the money was a pittance. What was much more precious was the status that came with it and the sense that someone else had told me that I, my creative work, was worth it, was worthy. It changed my sense of self, from an improper waif and stray, to a valid artist, from a hussy, to a woman with a place and purpose.

Status is dynamic and interactive. Money is too, actually - see the stock market. It is all one big game of choosing what we - individually and collectively - are willing to believe in. You can’t change your status on your own - it’s relational. But you are not alone. That is the whole point of Mothers Who Make - to let you know that you are not alone. I am here. Along with hundreds, thousands of others. We can help to give each other status, and we must, because no one else is going to do it. And it can be as simple, as powerful, as a change of name, of meaning, from a housewife to a sheltering-woman, or whatever reframing works for you. I think of the turnaround implicit in Lenka Clayton’s brilliant initiative ‘An Artist in Residency in Motherhood,’ - a way to make the pram in the hall, the wife in the house, not an obstruction to creative practice but the site of it.

This blog is a passionate plea, then, to myself to reframe how I think about unloading the dishwasher, and about writing this. I do not want to exorcise my ghosts but rather consciously to welcome them back in - to clear a space for both the housewife and the hussy, and my husband, because I don’t want anyone left out in the cold, anyone left alone. And it is a passionate plea to you, to value, to validate your need to make, whether or not you are getting paid for it, whether or not you have other paid work. It’s essential. I don’t have a load of money to dish out (I’m working on getting it - I promise!), but for now I do have a strong sense of your worthiness. I want to commission you. MWM wants to commission you. To permission you. To give you the permission to take your need to write, paint, sew, dance, film, play, run, sing, make, seriously.

So here are your questions, and instructions, for the month- serious ones:

What would you like to be commissioned to do? If you were given a pot of gold to make something this summer, what would you make?

Here - take that pot. It’s yours. You can afford it. You can afford the time. The effort. You can’t afford, and the world, (as in the world and his wife), definitely can’t afford to undervalue your work any longer. It is a disregard for care, for careful house-keeping, for the kind of leadership described by the old meaning of the word ‘huswyf’ - a woman in charge of a dwelling - that has resulted in our disastrous treatment of our collective dwelling, the earth. It is a disregard for care and creativity that is leaving us all, increasingly, unsheltered.

Like I said, it is essential work.

So, I want to commission you, to ‘permission’ you to do the work you want to do. Starting now. This summer.

One condition, that has everything and nothing to do with your ‘housekeeping’: let me know what you are going to do with your commission. Post below or come to a Mothers Who Make meeting.

Right, now I’d better go and get the kids dressed and hoover the cream-coloured carpet.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Don’t be Attached to the Results...

Once upon a time, fifteen years ago to be precise, I stepped into the rehearsal room of a company called Improbable. I was nervous, but Phelim McDermott, one of the Artistic Directors, told me that I only had to do four things. They were:

1) To turn up.

2) To pay attention.

3) To tell the truth.

4) To be open to the outcome - i.e not to be attached to the results.

That was it.

During rehearsals, that’s all I had to do.

Also in life, apparently, that’s all I had to do.

Reader, I married him. Phelim that is. And had two children with him.

Be open to the outcome…..

Becoming a wife and a mother was the result of that Improbable show - a happy outcome. But that fourth instruction is still the one I find the hardest to follow.

The instructions aren’t actually Phelim’s. They’re from Angeles Arrien’s work, The Fourfold Way, which draws on the Native American medicine wheel. I feel fairly confident about the first three - not that they aren’t challenging, ongoing practices, but that I have a sense of what each requires of me - how to be present, how to listen deeply, how to speak what’s true without judgement. But that fourth one? Not being attached to the results? Right now, in both my mothering and my making, this feels tough. My son is ten, about to leave his current school and start a new chapter of his life. Meanwhile, my novel is being prepared for publication. After a decade of harbouring both - a boy and a book - I am looking outwards with them, taking stock, focussing on the results, and I know I am attached to how they go - how can I not be?

First, to illustrate, let me tell you a story about the boy:

My son is autistic. He loves Dungeons and Dragons, and fantasy video games.

‘Warriors of Destiny’ by Riddley McDermott

He has been saving up to buy a Virtual Reality headset. Last week he bought it, but when we got it home, it turned out he needed a camera to go with it - the man in the shop had failed to tell him this. My son decided to return the headset and get his money back. He wanted to complain - complaining in public is something of a speciality of his. So off we went, back to CeX.

When my son was four or five his ability to go up to the lady behind the desk at Kew Gardens and let her know how deeply unhappy he was that the children’s play area was closed, was challenging, eccentric and kind of cute. As we went into CeX, I felt the increased pressure of his increased years - a different age, a different set of expectations. To cut a long speech short, my son did fine. I did not. He went up to the counter and launched in, gesticulating wildly, looking more at his own furious reflection in the perspex screen, still up from pandemic days, than at the non-plussed shop assistant stood behind it. But I felt panicked as I watched him, watching himself, being watched. I wanted to explain his behaviour, to mediate, apologise - I even tried to do so, at which my son waved me away. In that moment, part of me felt ashamed of him, of how he is, and then even more ashamed of myself for this. In that moment, I felt caught - attached to the results, anxious about how my son is turning out.

Afterwards, I did not want to read my pc parenting books, extolling the virtues of unconditional love (I have a shelf of them). I wanted some gruesome myths, scary fairy tales - the ones in which parents are horrible: disappointed or critical, competitive or jealous, the ones in which the mother gazes at the mirror to check who is the fairest and the best. And I wanted, too, the stories about monstrous children, about mothers who give birth to minotaurs, or pigs, or Cyclopes. I wanted these stories because they made me feel less alone, helped me know that - yes, this too is the territory of parenthood. The dark, difficult and, at times traumatic territory of expectations, of wanting certain results, for our children, for ourselves, which feels taboo because I have been raised and want to raise my children under the flag of freedom, of loving them exactly for who they are, openly, always.

Meanwhile, parallel to the story of the boy, is the story of the book:

Because when I came back from CeX, hungry for horrible myths, I found an email waiting in my inbox asking me to fill in ‘an author questionnaire’ about my novel, which, as it happens, is also a story of parenthood, based on a myth. The questionnaire came from the marketing department of the publisher, and it included questions like: ‘What inspired you to write this book?’ And ‘Are there any personal experiences which informed the work, about which you would be willing to talk?’ I dutifully typed my answers into my laptop but as I did so, a strange feeling stole over me. Because however accurate I tried to be, however much I tried to tell the truth of how and why I wrote the book, I could sense my meanings being changed by the context. I was having to tell everything backwards, as if I had always been working towards this point, when actually the whole blundering ten-year experience of writing it has been surprising, messy and difficult. But the effect was impossible to escape, like some fairy tale transformation of mud to gold, frog to prince, whatever I wrote, it felt glorified, solidified, because it was in support of the publication, the grand outcome - the result on which it all hangs, to which I am so fiercely attached.

So, there we have it.

Two very different moments: one in CeX with my son, trying to take his headset back, the other involving me, with my author questionnaire, trying to help sell my book, but in both instances, I felt hot and bothered about the outcome.

An outcome is often just that, I realise, a moment of coming out, of turning outwards. Both the complaint, and the questionnaire, involved a transition across a threshold, from a private place to a moment of contact with the outside world. And what occurs in that transition feels almost like a chemical reaction. Like a pot being put into the oven to be fired, or conversely, like a red-hot metal spoon being plunged into cold water to be set- it’s the moment when things harden. And the hardening is both an act of protection, something which maintains the shape of the object, keeps it intact, and an act of presentation, of pride, something which enables it to be put on display, seen, admired. And it’s inevitable - this moment of things hardening.

I go back to the advice I received in that Improbable rehearsal room - the instruction was not to avoid the result. It wasn’t even, “Don’t care about the result.” The advice was only not to be attached to what it is. Not to fix beforehand on what or how it should be.

But there is always a fixing, a firing, a hardening - that’s what I felt, in the shop, in front of my laptop, a fixing, which was the result itself coming into form. And I think this is what has confused me. The hardening is necessary, unavoidable. But what we can do, perhaps, is not to fixate on the fixing, not to harden around the hardening, but somehow to remain fluid, able to move, even as things set.

One more story, about the boy:

He has only three days of school left now. Last Friday I was invited, along with other parents, to come in and watch his class sing some songs, recite poems, and play recorder music - an end of term presentation. While the rest of the class obediently sang, recited, played, my son stood among them, saying nothing, grinning, but every now and then pulling crazy faces, or making dramatic gestures, some of which related to the words and music being shared, and some of which did not.

I watched him, entertaining himself, wanting to entertain us, managing the situation in his own way, and on this occasion, I didn’t want him to be any different to who he was, is. But I was acutely aware of how he looked to the outside world, of how the outside of him appeared- a weird, disruptive child, with special educational needs. And as I listened to the recorder music that my son wasn’t playing, I was surprised to find myself crying. I wasn’t disappointed. I didn’t want him to be joining in. I was crying because I had understood something: I reached for my bag, found a stubby pencil and the back of a receipt and wrote down this:

There’s always an inside story.

Even or especially at the outcome stage, even whilst everything around you is hardening into results, there is always an inside story. Not like a journalist relays it. Not an exclusive news story. Something much more subtle and secret. A soft, unfolding, slippery, weird, disruptive thing.

This thought helps me, at last, fifteen years later, understand how I might remain open to the outcome, unattached to the results. I believe it has to do with attending to the inside story, as the results come out. And I think it is a practice that will send me round again to the beginning, back to step one, to simply showing up, to listening, to telling the truth. It’s like that fourth instruction is nothing more or less than an arrow which points back to the start. It feels like a children’s game of Grandmother’s Footsteps. You stand on the starting line, you pay attention to the Grandmother’s back, you creep forwards. And then, when she turns round you have to freeze. This is the moment you are seen, judged. You go statue-still, fix your position - it’s part of the game. But an equally intrinsic part of the game is the wobbling, breathing, teetering that happens inside the moment of fixing. Grandmother sees this: “You’re moving!” she says- and sends you back to the start. And that’s not a failure. It’s the only result that matters - that you are staying in the game, beginning again. Turning up. Listening. Being true. Taking another tiptoe step.

And on it goes.

I want to try to remember this as I go through the next year, of publishing my book, of home educating my son (which will actually involve going out of the home with him into new environments, having new encounters). Because I know there can be so much pain in the hardening. The stories surrounding the results - who my son should be, how I want my book to be received - are powerful. It is so easy to become set in stone, a hard reflection in the glass, the fairest and most miserable of them all, hardened against my children, my work, myself. It is so easy to forget the inside story.

But the results are never more than a fired pot, a cooled spoon- one outcome, outline, the cast of one moment in time – nothing to which I need attach. They can be sloughed, like a snake’s skin, and left behind. Meanwhile, the inside story is always there - soft, flexible, alive - it wants to slide away, showing up where it can, listening, telling you, me, the children, its wise, true, slippery tale. Once upon a time…..

So here are your questions for the month:

Can you name a moment when you have been fixed on the results?

For yourself? For your children? For your work?

And then can you name, in each instance, what the inside story was?

What was the slippery thing, that was waiting to show up, and tell its tale?

P.s. And now, as I write, it is my son’s last day, and yesterday he went for a walk with his class and they found a frog, which they called Amber - I was wondering what image might go with this blog and here she is - the slippery inside story herself, better than any prince.

Amber the frog, photo: Marianne Romeo

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Antidotes for Post-Natal (or any other kind of) Depression and Some Helpful Fairies

The Fairy of Beauty, by Tenar McDermott

Whilst Jubilees and jubilation are on the UK’s official agenda as the month begins, whilst honours are announced and cheering is expected, I am feeling down. I feel it in my chest - a dull, blunt weight. I don’t believe, when I think of the many present troubles in the world, that I have any right to this feeling. I can identify a few reasons for it, but they seem either absurdly trivial, or even that they should be cause for celebration, not depression. Here they are:

-The children and I have made it to the end of all seven Harry Potter books.

-My son will soon have made it to the end of his time at his present school.

-Twenty-five rejections and one offer later, I have a potential book deal for my novel.

I should be feeling elated. Grateful.

I can do the gratitude, but the elation eludes me.

The frightened tension and fierce exhilaration involved in the act of letting go are over (see last month’s blog). Four years ago we moved to this house so that my son could attend the Steiner school near here and so that I could write my novel. These things are done. We finished Harry Potter - the magic is over. This chapter of our lives is ending. And yet things have a habit of carrying on - a well-known difficulty when grappling with any kind of grief. The clocks don’t stop.

I think I know what this is.

Post-creative depression.

I didn’t suffer from post-natal depression. But I might have. I felt it near. Months of waiting for this moment, and now here it was - I had a baby - and it was hard. I was meant to be happy, and yet I mainly felt exhausted, anxious, lost and leaky. Everything was leaking - eyes, breasts, womb, sense of self. I, my body, had done a phenomenal thing - grown a whole person, birthed them over a five-day labour- but it turned out that making a life wasn’t the main event after all. Now I had to care for it. Now I had to be a responsible, capable adult day and night. Now I had to be mum.