Photo

THE LAST GASP: SCUMMING IT IN THE FEW BARS IN AMERICA WHERE YOU CAN STILL (SECRETLY) SMOKE

‘If and when you stumble upon a bar you can smoke in, you know you're among true degenerates. I mean that positively.’

We’re such stoners that 4/20 isn’t just a day, it’s an entire week. And it’s not just weed we love, it’s the act of smoking and everything even loosely related to breathing in toxic fumes — whether that’s chain-smoking cigarettes, vaping Juuls, suffocating a rack of ribs, or hell, even committing arson! Welcome to our exploration of all things smoke.

When Brendan, a 34-year-old in Chicago, wants to pull endless cigs under the roof of a dingy bar, he knows exactly where to go: Richard’s.

Somehow, despite Illinois state laws barring smoking indoors for more than a decade, Richard’s skates around the issue. Some incorrectly theorize that they’ve established the bar as a “smoking club,” and thus, found a loophole in the law. Others just say it’s a “cop bar,” so they’re allowed to do whatever they want.

When I ask a bartender at Richard’s, she flatly tells me, “We don’t allow smoking in here,” and that “it’s illegal to smoke anywhere indoors in the city.” Richard’s grouchy bartender has former Surgeon General C. Everett Koop to thank, who in 1986 released a report titled “The Health Consequences of Involuntary Smoking,” which detailed the litany of health issues that can arise from secondhand smoke. To that end, here’s a fun video on the dangers of smoking and secondhand smoke, if you’re not already familiar:

The same year, the Americans for Nonsmokers’ Rights became a national group, putting pressure on politicians to pass smoke-free workplace laws. And so, slowly but surely, public places like airlines and government buildings began to ban smoking. Next, starting in the early 2000s, several states followed California’s lead in passing state-wide legislation that bans people from smoking cigarettes in any enclosed workplaces — including bars and restaurants.

While there isn’t yet a federal ban on smoking indoors, 28 states now have total bans on smoking in all-indoor workplaces. Another 12 states have bans, but with exemptions carved out for things like number of employees, whether it’s a private club or the percentage of profit the business makes from food. Illinois, however, is among the states that’s banned smoking indoors outright. Yet the patrons still smoke away. And if you don’t believe me, take it from yelpers Rachel, Maddie and Christopher:

Smoking at Richard’s is a pretty well-known secret in Chicago, perhaps making it an apt defense against the burgeoning population of yuppie apartment complexes filled with bougie young business bros too scared to take public transportation downtown. Basically, Richard’s, a stone’s throw from Chicago’s business district, stands as a dirtbag’s port in a gentrification storm. “There’s fewer and fewer true dive bars in Chicago these days, and Richard’s is the truest dive bar experience around,” says Brendan, a frequent patron. “It’s scummy, smoky, the patrons look like they haven’t left in 20 years, and if you’re not a regular, you’ll feel a little out of place, which is what you’re supposed to feel. It’s perfect for the last stop — when you get to the point in the night when everything tastes the same anyway, spend $3 on a shitty beer and smoke away.”

For Brendan, the thrill of smoking in Richard’s isn’t about doing something technically illegal, “[it’s] more like when you go to a fancy dinner and it feels extra special because you only do it a few times a year. For some reason, you’re still allowed to smoke in there — they even sell cigarettes! But you get excited, and really go all out. Like, you smoke way more. Way, way more. When you can smoke in the bar, it’s such a novelty that you basically chain smoke until you feel like shit.”

Brendan was in college at the University of Illinois in Champaign-Urbana on January 1, 2008, when the smoking ban was passed. “They banned smoking in bars at the stroke of midnight,” he recalls. “Even if the scent of smoke hung in the air from years of indoor smoking, [after the ban] it was a pretty stark contrast — coming home only kinda smelling like smoke than feeling like it had soaked into your bones.”

As a nonsmoker, I’ve never understood the appeal of smoking in bars, and going to places like Richard’s is a nightmare for me. My clothes stink. My throat and eyes burn. And my precious runner’s lungs go into overdrive trying to hack out the impurities. But for guys like Brendan, who’ve “paired smokes with beer since college,” it’s like “donuts and coffee, just a million times worse for you.”

“It’s some weird alchemy,” he tells me. “I’m a big shitty beer guy. Busch Light basically tastes exactly like the color it is, mild and relatively flavorless with a little bit of bitter tang. A Camel Light stands in such stark contrast. So you have a mildly bitter, cold fluid sitting on your tongue and washes down your throat, then there’s this intensely bitter smoke that just fills your entire fucking face.”

Even though Brendan makes a point of seeking out smoking bars in his world travels — “Outside of Japan, most places I’ve traveled in the U.S. and internationally have banned smoking in bars, but if and when you stumble upon a bar you can smoke in, you know you’re among true degenerates. I mean that positively” — he doesn’t miss being able to smoke in every bar. “If you want to smoke, you should do your best not to make other people suffer because of your (admittedly) pretty gross habit,” he says.

What happens, though, if you work in a bar where people smoke?

A 38-year-old woman named Meredith tends bar at a “small dive” in Connecticut, another state where smoking indoors is strictly outlawed. When she got the job, the bar’s owner directed her to allow smoking inside the bar “so long as it isn’t too busy,” she tells me, adding that the owner himself “always smokes inside.”

For the most part, patrons “don’t chain smoke or take advantage,” but when she works, she tends to smoke more herself. “I don’t smoke in my home,” she says. “So I tend to smoke more at [the bar], even more than other jobs because I don’t have to wait for a break to light up.” According to a study published in The British Medical Journal, Meredith’s increase in smoking isn’t an outlier. In what the study deems “socially cued” smoking, the study found that of the smokers who patronized bars and clubs that allowed smoking, “70 percent reported smoking more in these settings and 25 percent indicated they would be likely to quit if smoking were banned in social venues.”

Though Meredith doesn’t mind that her bar allows smoking, and says it wouldn’t be a deciding factor in taking another job, she does admit that there “are no good parts” about working in a bar that allows smoking. “People are usually happy when they find out they can smoke inside,” she says, “but I hate that I smoke more when I’m there, and it can turn off non-smokers.”

Since Meredith’s bar isn’t working within a loophole, employees are asked to hide all smoking paraphernalia when the cops come. “If the cops come, everything is put away,” she says. “But they’ve never said anything about the smell or smoke when they’ve been here. Otherwise, we keep ashtrays put away when they’re not in use and have fans that ventilate pretty well.”

When people try to “get away with smoking” during busy times, Meredith has to send them outside. “For the most part, they’re respectful when I remind them of the rules, but I’ve had people get mad about having to go out. One girl even called the owner when I asked her to go out, and he told her she had to listen to the bartender.” Plus, Meredith adds, “One of our best regulars doesn’t like smoke,” she says, “so most people know to go outside if he’s at the bar.”

Nicole Bournival is another bartender at a smoking bar: The Rimmon Club, a small spot in Manchester, New Hampshire. She doesn’t smoke herself, but the place is a smoking bar through and through. Bournival explains that smoking in bars is outlawed in New Hampshire, but The Rimmon Club was “grandfathered in” and allows smoking by claiming to be a private smoking club that’s not technically “open to the public.” “If you’re a club member or member’s visitor, you’re allowed to smoke. You just have to be signed in if you’re a guest, and to become a member, it’s $40 for the first two years and $30 every two years after,” Bournival explains. A self-proclaimed “sassy bartender,” Bournival says she “wouldn’t fit very well in the public bars, so I tend to stick to the private ones, where you can be a little rough around the edges.”

For Bournival, who says she hasn’t noticed any health issues with regards to secondhand smoke, the worst part is coming home smelling — especially after cleaners release the layers of cigarette toxins that deposit on various surfaces at the bar. “You go home smelling like an ashtray!” she tells me. “Otherwise, it doesn’t really get to me health-wise. It’s just annoying with stinking up my hair and clothes. But I don’t really notice it while I’m at work. It’s only when I get home that I tend to notice it.”

“Of course, there are people who complain, as people complain about everything these days,” she laughs, “but some people choose not to come in because of it, and that’s okay. Sometimes husbands or wives come in without their significant others because they don’t like the smell. But for the most part, it’s not too bad. We do have smoke eaters around the club in several different spots, so it does cut it down.”

Stephanie Litzinger has tended bar at an Eagles Club in Indiana for more than two years now. Though Indiana has “strong anti-smoking laws in effect,” per the American Lung Association, the state still allows smoking in private clubs, such as her Fraternal Order of Eagles Club. “It isn’t something I could do forever,” she says. “I’m 30, and I get coughs more often, for sure. I also swear my skin looks way more dry than it did when I started.” Litzinger says she smokes along with customers because she doesn’t want them to think she’s judging them. “You want your bartender to act like a built-in friend when you come in, especially when you stroll in solo,” she says. “So I end up smoking way more than I do at home. When I have a couple of days off in a row, I barely smoke, because I’m so over the smell and taste of cigarettes.”

As for how much people smoke in Litzinger’s bar, she says “most people have two packs on them — one of the packs already open by the time they’ve gotten there. They go through that one and put a good dent in the other one by the time they’re a few in. It’s easy for me to track as I throw away their empty packs and continuously dump their ashtray.” She adds that while regulars say they wouldn’t come back to the bar if they couldn’t smoke, “I hear more from other people, though, that they won’t come in because of the smoke. I think smoking bars drive away a lot of potential business.”

That said, Litzinger enjoys how smoking allows her to categorize different customers:

“Business people that have a little bit of a wild side will come in, steer clear for a few beers but inevitably end up bumming one from whomever they end up chatting with after all of the ‘Where ya from?’ questions.”

“You have the blue-collar, hard-working guy who comes in after work with an off-brand pack. He tips the same amount each time — two or three bucks. Sits at the same spot, not a gold mine but consistent.”

“You have the half-pack, pierced tatted kids. They smoke 100s, typically menthols, and have tons of half-smoked cigs in their pack. They dig change out of their pockets for the pool table, may throw a dollar or two in the jukebox and casually try to mooch for drinks.”

“Then you have the Virginia Slim Karens. They puff out of the side of their mouths, and their haircuts resemble a Pomeranian. They act superior but are very lonely inside.”

“Finally, there are the cigar smokers. They typically stink the most — and cleanup is harder — but they have money and love to show it.”

Aside from people watching, The Rimmon Club’s Bournival says there are other good things about working in a smoking bar — mainly that it’s different. “There aren’t many [smoking bars] located in the city, so people who enjoy smoking like and notice that when they come in, [so] it helps them to become members at our bar.”

“Still, if people ask me for a butt (seeing I don’t smoke), I tend to moon them,” she warns. “That’s the only butt I carry on me.”

0 notes

Photo

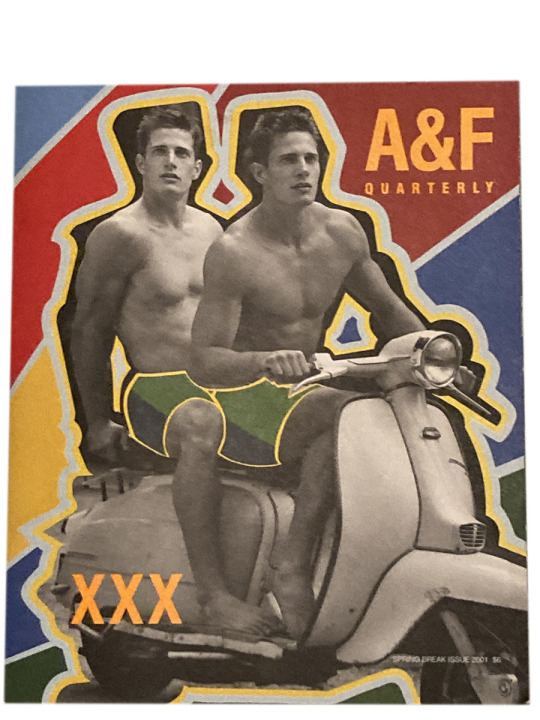

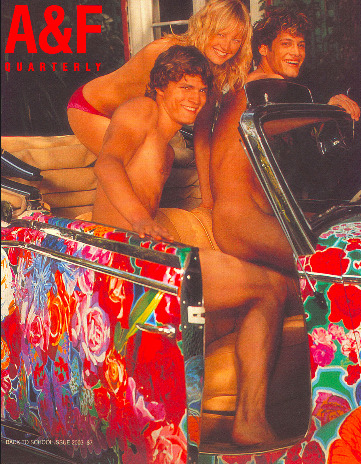

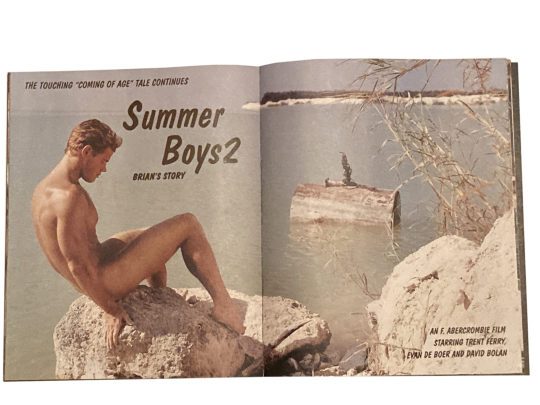

SEX, LIES AND CHEAP COLOGNE: AN ORAL HISTORY OF ABERCROMBIE & FITCH’S SOFTCORE PORN MAG

The story of how an oversexed, strangely intellectual magazine by a polo shirt brand completed the improbable task of changing the course of sexuality in America’s malls, homes and moose-print boxers

Abercrombie & Fitch CEO Mike Jeffries was a shrewd businessman, but he didn’t always make the best decisions. Between the blatantly racist T-shirts he signed off on, the child thongs he called “cute” and the series of public statements he made admitting that his brand intentionally excluded anyone who wasn’t “cool” and “good-looking” with “great attitudes and a lot of friends,” it’s no wonder that he spent the majority of his reign at Abercrombie in hot water. (For the uninitiated, Abercrombie made what fashion writer Natasha Stagg calls “sexy versions of the clothes kids already wore to school: T-shirts and jeans, stuff you could toss a football in or throw on the grass if everyone decided to go skinny-dipping.” More importantly, as she writes in her book Sleeveless, it was “for those who were casually peaking in high school.” It, meanwhile, peaked in the 1990s.)

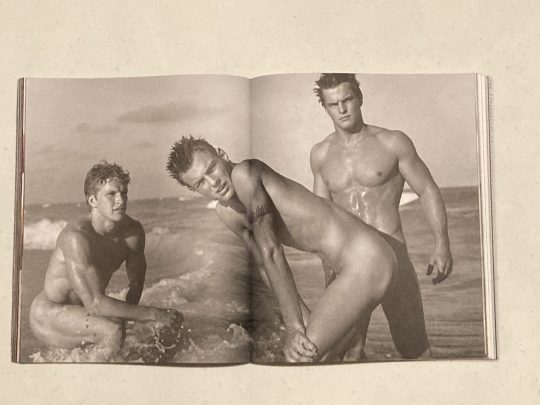

An exception to Jeffries’ questionable CEO-ing would be A&F Quarterly, the glorious, controversial and questionably pornographic “magalog” he created at the height of the brand’s popularity in 1997 in order to connect “youth and sex” to its image. Woven in amongst surprisingly thoughtful interviews with A-list humans like Spike Lee, Bret Easton Ellis, Rudy Guiliani and Lil’ Kim was a cascade of naked photos from photographer Bruce Weber which showed nubile youngs in various states of undress. They were frolicking, they were caressing and they were deep in the throes of experimenting with types of sex that — at the time — had never been portrayed by mainstream brands.

With issue titles such as “XXX,” “The Pleasure Principle” and “Naughty and Nice,” the Quarterly dove headfirst into the risque. During its 25-issue run between 1997 and 2003, it printed interviews with porn star Jenna Jameson, offered sex advice on how to “go down” in public and suggested — on multiple occasions — that its readers dabble in group sex. One issue published an article on how to be a “Web exhibitionist,” another featured a Slovenian philosopher barking orders to “learn sex” at school and big-dick Ron Jeremy even stopped by to talk about performing oral sex on himself and using a cast made from his own penis.

The actual Abercrombie clothing being modeled in the magalog was an afterthought, appearing in Weber’s photos as more of an impediment to nudity than an actual, purchasable item. The whole thing was, as journalist Harris Sockel put it in an Human Parts essay, “20 percent merch, 20 percent talk and 100 percent soft-core aspirational porn.”

None of this would have been vexing had a more adult-oriented brand been the ones hawking it, but Abercrombie & Fitch was — and still is — marketed toward suspiciously toned teenage field hockey players named Brett. Though he might have looked like a man in his big salmon-pink polo, Brett was but a child. Abercrombie was fond of saying its clothing was for college-aged clientele, but we all knew where its real haute runway took place — inside the crowded halls of every middle school in Ohio.

The Quarterly, too, was intended for college kids, and to prove it, Abercrombie shrink-wrapped it in plastic and sold only to those over 18 for $6 a pop. You could buy it as a subscription, of course, but it was more commonly found in-store, nestled alongside A&F’s cargo shorts and “thongs for 10-year-olds,” a questionable placement that prompted concerned parents, conservatives and Christians to accuse Abercrombie of sullying their children’s minds with impure thoughts.

As such, the Quarterly became the subject of a mounting number of boycotts, protests and controversies that some believe were responsible for its eventual demise. By the time circulation peaked at 1.2 million in 2003, it had been denounced by organizations like the National Coalition for the Protection of Children and Families, Mothers Against Drunk Driving, the American Decency Association, Focus on the Family, the National Organization for Women and, of course, the Catholic League.

Yet the outrage against the Quarterly was matched — if not exceeded — by its cult following, who found its frank portrayal of sexuality to be transcendent. Journalists, artists and the teens whose hands it fell into adored the magazine, and its rarity — plus its utter absurdity — makes it a sought-after collector’s item to this day.

At the same time, few people know about the Quarterly and even fewer realize what it meant to the generations of young people discovering themselves and their sexualities through the unlikely lens of branded content. As journalist Emily Lever puts it, “There’s no weirder way to learn about sex than to pick up a magazine by Abercrombie & Fitch — a brand for hot, mean mostly white kids who shoved you into lockers — but, I guess I’ll take it?”

This is the story of how an oversexed and strangely intellectual magazine by a polo shirt brand completed the improbable task of changing the course of sexuality in America’s malls, homes and moose-print boxers.

AND IN THE BEGINNING, THERE WAS ASS

The first issue A&F Quarterly debuted in June 1997. With 70-ish pages of full-color hard bodies, it was relatively tame compared to later editions, but it quickly became popular when Abercrombie’s nubile clientele realized it was a paper-backed portal into an adult world of sex, nudity and the kind of unbridled sensory hedonism their parents warned them about. As rumors of its legend began to spread, people began to wonder: What the hell is A&F Quarterly, and why is it printing ass for teens?

Emily Lever, journalist and chronicler of the Quarterly’s absurdist philosophical leanings: A&F Quarterly was an in-house magazine put together by Abercrombie & Fitch that published a who’s who of literati to accompany their images of young adult and teen bodies in order to hawk expensive distressed jeans and polo shirts to kids who would shove you inside a locker.

Alissa Quart, author of Branded: The Buying and Selling of Teenagers and director of the Economic Hardship Reporting Project: From what I recall, it had a Bruce Weber-y vibe — gorgeous young men and teens unapologetically objectified, a leering retro pin-up element, also sort of like the highly stylized, sexed-up, nostalgic 1980s and 1990s black-and-white Guess ads. Men — boys, really — were photographed without their shirts, elaborately muscled abs, sometimes naked.

Harris Sockel, in his Human Parts essay: [It was] Playboy crossed with Fratmen.com and a bit of Field & Stream. The Quarterly made my hormones do a kick line across my frontal lobe. I wanted to nibble the soy ink for snack until sunrise. To absorb it so deeply I sweat grey drops onto my pillow. To rip a page from that issue and fold it into a paper flower and stick it all the way up my ass until it came out my mouth.

Lever: Yeah, it was hot. But it was also extraordinarily literary. It featured big-time thinkers, writers and philosophers — stuff that was supposedly intended to expand your mind. It was way too high-brow for the average Abercrombie teen, and its existence made almost no sense given what the brand represented.

Savas Abadsidis, editor-in-chief, 1997-2003: There was nothing else like it. We were the first mainstream brand to combine playful, irreverent, intellectual content with sex and youth in this beautiful, high-art magazine format. Was it controversial? Sure. But it made the entire country take notice.

What they didn’t necessarily see, however, was what was going on behind the scenes. Not only were we the first brand to do this kind of advertising, we were also the first big brand to normalize gay culture for a mainstream audience, expose America’s youth to some of the era’s most progressive thinkers and use our platform to address sexuality in a useful, hands-on way. And you wouldn’t necessarily expect that from Abercrombie. That’s what made it so cool.

It all began in 1996. I was 22 and working at a temp job for a prominent New York architect who happened to be friends with Sam Shahid, a big-time creative director for Calvin Klein, Banana Republic and later, Abercrombie & Fitch. He was looking for an assistant. I had taken a deferment to go to law school and was looking for a job for that interim year, so I applied. I got in.

It was a horrible gig at first. Just awful, Devil Wears Prada-type stuff. I left crying many nights. But I had two things going for me. The first was that Abercrombie had a really small office in the West Village. Mike Jeffries, the president and CEO of Abercrombie, used to come in. He wore flip flops, had a desk made out of a surfboard and began each sentence with the word “Dude.”

Mike Jeffries, ex-CEO of Abercrombie & Fitch, speaking to Salon in 2006: Dude, I’m not an old fart who wears his jeans up at his shoulders.

Abadsidis: I didn’t know it at the time, but Mike was gay (I wouldn’t find out until much later). I think that was part of the reason why he and Sam — who was also gay — took me under their wing. They actually didn’t realize that I was, too — it’s not like we all sat around a bonfire at Fire Island and talked about how us gay guys were infiltrating Abercrombie — but that dynamic dovetailed nicely with Bruce’s photography for both the brand and the Quarterly, and it certainly set the tone for what was to come. I was grateful to get what amounted to an unofficial apprenticeship from both Mike and Sam, and eventually, they had me doing much more involved tasks than I was hired to do.

One of them was sitting in on important meetings. At the time, Mike was inviting all these different editors from magazines like Interview, Men’s Journal and Rolling Stone to come in and brainstorm ideas for what the Quarterly could be, but their ideas were flat. They felt like ideas coming from 45-year-olds writing for college kids, and I could tell Mike was getting frustrated by how little they seemed to grasp what he wanted.

One day in a meeting, one of the magazine editors threw out an idea. Without even acknowledging him, Mike turned to me. “Savas,” he asked. “What do you think about that?”

My mind raced — I could tell he was testing me. If I flubbed the answer, I’d be done. I briefly considered censoring myself, but then I thought better. What did I have to lose? I was young. Surely, I’d find another summer job. “I don’t think it’s a great idea,” I told him.

Apparently, that was the right answer. Mike practically threw the guy out of the room.

After that, I started to think more about what I’d want to see out of a magazine. I was just out of college as a French comparative literature major at Vassar, and I was super into that sort of 1950s-style Esquire journalism with the dapper closing essay. I was deep into The New Yorker, Interview Magazine, 1990s-era Details, MAD Magazine and 1980s pop star mags like Tiger Beat, too — those were all an influence. I also loved philosophy, social theory and comics. And graphic novels. You know — college stuff. Then it hit me: If the magazine was for people like me, why not get actual college kids — not 50-year-olds — to create our content?

I suspected my ideas were what they were looking for and knew they’d look fresh compared to what other editors were throwing out, so I decided to take a risk. I got up at 2 a.m. and typed out a 20-page proposal for what I thought the Quarterly should be. The next morning, I faxed a copy to Mike. I left another on Sam’s desk.

About a (very anxious) week later, Sam called me into his office and told me to pick up his phone. Mike was on the other line. As I reached for the receiver, he leaned over to me and said, “Who the fuck do you think you are?”

I didn’t even have time to comprehend what that meant before Mike’s voice was in my ear. “Congratulations, kid,” he told me. “You get one shot.”

Shortly thereafter, I was promoted from Sam’s assistant to the completely green, 23-year-old editor-in-chief of the Quarterly. It was a Jerry Maguire moment. I was thrilled and terrified at the same time.

They gave me a month to put together a staff and get the first issue out. Bruce Weber was named as its exclusive photographer — he’d already been shooting ads and campaigns for Abercrombie — and Sam was the creative director. As for me, I knew I’d need an editorial staff, and stat.

HOLY SHIT, THERE ARE NO LIMITS

Abadsidis quickly throws together a team composed of two college buddies, Patrick Carone and Gary Kon, who he describes as “pretty funny and stuff.” Carone became the only straight guy on the editorial side. Kon is Jewish and gay. The three of them vow to stay as true to the idealized college experience as possible with their content — even if it means chasing white whales.

Abadsidis: I can’t remember the exact starting budget, but it was upwards of a few million, probably much larger than most magazines get for their first issue! But our budget was also Bruce’s budget. He was getting advertising money, so we were well taken care of in that regard.

We weren’t really expected to turn a profit, though. That was never the point. Come to think of it, I don’t even think we tracked how much the magazine impacted clothing sales, although from what I can remember, clothing sales bumped up double digits every quarter after we launched (for a while, at least). [This statement is unverified.] But that didn’t matter: Our mission was just to set the brand image and make people aware of us. That was our version of success. We were also our only advertiser for a while, so we could get away with a lot of stuff that other publications couldn’t.

Gary Kon, managing editor, 1997-2003: When Savas offered me the job, I jumped at the opportunity. I’d already interned for Sam, and I’d have to scan hundreds of Bruce Weber images that he shot for Abercrombie as part of the job. And I fell in love with his work. It was the visual connection that seduced me. Weber’s photos were like a new Greek mythology; the men and women depicted in the photos were both idealized and sexualized. As a gay kid, who was pretty comfortable by that time in my own skin, I had no problem recognizing the eroticism in his work.

Abadsidis: Me, Gary and Patrick was definitely something special. I don’t think I’ll ever have an opportunity to create anything like that again. I was a huge comic book fan. If I had to describe it, it’s the closest thing I’ll ever come to Stan Lee’s Marvel comics bullpen. Pretty much everyone I hired was super unique. We weren’t all gay (maybe half of us were) but few of us really adhered to the Abercrombie image.

I think Sean came on in 2001.

Sean T. Collins, managing editor, 2001-2003: I was a little skittish about it at first because Abercrombie & Fitch represented everything I was not. They marketed, almost exclusively, to the lacrosse players that called me names I cannot repeat. It was very preppy, and that was not me at all.

I was alternative, maaan. I was a big fan of Nine Inch Nails. I wore a lot of black. A&F was everything I wasn’t, and in a way, everything that had tormented me as a kid. The irony of me working for them was palpable, but what I learned very quickly was that at the Quarterly, you could do anything that you wanted.

One of my first articles was an interview with Clive Barker, the writer and director of Hellraiser (he also wrote Candyman). Now, if you’ve seen Hellraiser, you can imagine just how far of a departure a sadomasochistic horror film was from Abercrombie & Fitch, but getting him to sign on was easy. He’s gay, and at the time, he was super ripped. I think he appreciated the extravagant gayness of the Weber stuff in particular. He was also a photographer, and his husband was, too. I think he recognized what was going on with the photography.

We had an unlimited expense budget, so I took him out for drinks at the Four Seasons. I talked to him for hours, and then he invited me to go back to his house and hang out and see his art studio. He had three mansions in a row on Sunset in Los Angeles, up in the hills. One for his office, one for his actual domicile and one that was a painting studio. I got to see that. I was just a 23-year-old kid. This was my first job out of college, and I felt like Cameron Crowe from Almost Famous. After that, I was like, “Holy shit, there are no limits.”

Kon: I have to credit Savas with pushing us to work without limitations. We were very lucky. At some point during my tenure, I realized that as long as we worked within our (sizable) budget, we had almost full autonomy. We could plan trips to Hollywood to shoot our favorite actors. We could travel to Thailand to reenact our version of The Beach. We could tag along to London or Rome or wherever Bruce was shooting the catalog. We could stroll into the office at 11 a.m. and work until 11 p.m.

Collins: If I wanted to talk to Bettie Page, the pinup model from the 1950s, they’d be like, “Okay, sure.” If I wanted to feature Underworld, my favorite electronic music band, it was, “Sure, go ahead.” It was total editorial freedom, which was so strange knowing how specific of a person the “Abercrombie type was.” I’ve been writing for two decades now, and I’ve never experienced anything like it since.

Abadsidis: Everyone wanted to be in it, too. At first, it was just indie musicians. But then, in the second issue, we snagged Lil’ Kim. That’s when I knew we’d made it big. She was into it — she loved everything about the Quarterly. A lot of people did. The whole high-brow/low-brow thing was really appealing, and the idea of going to college, reading good books, getting drunk and having sex felt uniquely nostalgic and fresh in the context of America back then. Clinton was getting impeached for getting a blow job. It was just a weird, puritanical time, and the Quarterly gave people a national platform to let their freak flag fly.

We had Rudy Guiliani, early Britney Spears, Paula Abdul. There was the New York issue where we talked about the Harlem Renaissance. Spike Lee — one of my idols — asked me if he could be in it. He’d done advertising, you know? I remember him being like, “Yo, this is the deal. I’ve got to give you mad props. This is the dopest thing out right now, advertising-wise.”

We had big-time philosophers and literary figures, too. They were great. We wanted to mimic the experience of being in college and having your mind expanded, so we got writers like Bret Easton Ellis and Michael Cunningham on board. There was a whole Sex Ed issue plastered with musings from Slovenian philosopher Slavoj Žižek, a friend of a professor’s from college. I believe Jonathan Franzen was in there, too.

Jonathan Franzen, award-winning novelist and essayist: I gave hundreds of interviews between 1997 and 2003, almost all of them at the request of various publishers. One of them must have thought it was a good idea to talk to A&F. The fact that I apparently did (I don’t remember it) signifies nothing except that I felt grateful to my publishers.

Collins: We got a lot of weirdos, too. John Edward, the guy who talked to dead people. Chuck Palahniuk, who wrote Fight Club. At the time, it didn’t have the meathead reputation that it does now. It was legitimately looked at as this piece of anti-corporate, anti-capitalist art, the irony of which was just delightful given that we were a capitalist brand trying to sell polo shirts and $90 ripped jeans.

Abadsidis: The only guy who refused an interview was Donald Trump! I have a feeling his 90-year-old secretary had something to do with it. Though we were technically a magalog and did belong to the brand, our stuff was just really visionary. David Keeps, who was the editor of Details at the time, always defended the Quarterly as a real magazine and publicly said that we were doing more innovative stories than most “real” magazines at a time.

ASPIRATIONAL HOMOEROTICS

It’s no secret that the photography and creative direction of Weber and Shahid contained homoerotic undertones. Irreverent, minimal and moody, it was suggestive without being literal, spinning entire storylines into a single frame. At the same time, it was too idealized to be “real.” The queerness that their photos showed was, as Collins puts it, “aspirational,” meaning that like the mostly white, ab-riddled models instructed to sell cargo shorts by taking them off, they didn’t necessarily represent the full reality of what queerness actually was.

Still, the photos that the Quarterly published during its seven-year run did more to normalize and represent queerness and non-monogamy than any other mainstream brand at the time — weird, considering that Abercrombie’s target market was hegemonic suburbanites whose parents bred genetically pure golden retrievers and had cabins in Vail. Without these photos, the Quarterly might have read more as a minor-league Esquire or Ivy League MAD Magazine, but with them, it became one of the least-discussed, most under-appreciated items queer history.

Collins: Our editorial content — which almost functioned as a parody of so-called “Abercrombie people” — was always accompanied by this extremely beautiful photography that was also extremely queer. But it was never explicitly so. It was all this nudge, nudge, wink, wink stuff. I don’t know how you could miss it, though. The homoeroticism was so overt.

Abadsidis: You’d have had to have been blind not to consider the imagery homoerotic (though, it was really in the eye of the beholder). We had the Carlson twins posing on the cover and riding a motorcycle. We had a drag queen named Candis Cayne. There was a lesbian couple kissing at a wedding.

Kon: David Sedaris, Gus Van Sant, Gregg Araki, Avenue Q, Stan Lee, Peaches, Fischerspooner… you could teach a queer theory class with everyone we featured.

Abadsidis: At the same time, we never labeled anything as “gay” or “lesbian” or “queer.” We never came out and said, “Welcome to our gay magazine!” and we never had a meeting where we were like, “Okay, guys, let’s figure out how to make this thing gay.” It was more nonchalant. The imagery implied it without saying it.

Hampton Carney, A&F Quarterly spokesperson, 1999-2003: The message we were sending was clear: “You do you, whatever that is. Have fun!”

Abadsidis: That was a very 1990s thing.

Collins: There was a specific brand of Abercrombie gayness that got shown, though. The word that they always used to describe Abercrombie as a brand was “aspirational.” They didn’t want to make it like an everyday, normal-people brand. They wanted it to be associated with money, glamour and that WASP-y aesthetic. So all the gay raunch of it was presented within the context of what appeared to be a very square, nuclear family: white, wealthy and secure.

At the same time, that was really when same-sex marriage was kicking off as a political issue. I think you can see a commonality in how Abercrombie was essentially making an argument that you could be a normie and also be gay. That was a newish thing at the time (though I’m barely an expert as I’m not gay myself). Still, I can’t help but see a resonance between coming up with this clandestine content that normalized being gay at the same time this big political fight that was brewing.

Maybe being more forward about it would have come across as “too political.”

Abadsidis: Part of me wishes we’d gone a little further with being more outwardly queer, but I don’t think the time was right. Maybe with a braver CEO — no one at the time was brave enough to take on queerness or gay rights as a mainstream brand, including us — and that’s why few people remember the Quarterly as the sort of transcendent queer thing that it was.

Kon: It’s never been credited as such, but the Quarterly is really an item of gay history. I don’t think we were pushing a “gay” or “metrosexual” lifestyle on people as much as we were showing that it already existed, even out in Middle America. Perhaps that’s what made people uncomfortable. We took that thread of counterculture and taboo that ran through the imagery and continued it into the editorial content. We dealt with topics like drinking, drugs, religion, politics and sex. Again, these are issues young people dealt with daily, but were rarely editorialized.

At Vassar, there was a yearly party called The Homo Hop. It was one of the biggest parties of the year and leaned on Vassar’s history as a women’s college. I bring this up because, on the night of my freshman Homo Hop, I was instructed that each student had to do something sexually that they had never done, and one drug that they had never done. It wasn’t that you had to be gay, but you had to experience something that was new and different. I think that translated well into the Quarterly. Yes, there were a bunch of gay guys writing and shooting and drawing images. But we were simply trying to expose Cargo Short Brett to ideas, images, artists, books, writers and directors that he may have never heard of before. Our shared experiences would become his.

Collins: It was culture jamming, really.

Abadsidis: It was also very “college” to be fluid or experimental without labeling it. I think it’s safe to say that college is one of the gayest places there is in life, maybe not sexually, but definitely in terms of having your mind expanded about different types of people.

Carney: I was in a frat. I’d see fraternity brothers streaking across campus together. It was never a big deal. There are a lot more people in the middle of either extreme of sexuality than people talk about. We’re not one and 10 — we’re one through 10, if you will. That kind of stuff has always happened on college campuses, and that’s the kind of mentality we had around sex. We just happened to editorialize it really beautifully.

Collins: There’s a Barbara Kruger print that reminds me of the mood we were trying to capture: It reads: “You construct intricate rituals which allow you to touch the skin of other men.” That’s basically what Abercrombie & Fitch was. It was an intricate ritual that allowed sunkissed lacrosse players to metaphorically touch the skin of other men.

Carney: You know what’s funny, though? It was never the gay stuff people had a problem with. It was everything else.

LET THE CONTROVERSIES BEGIN

For almost every moment of its seven-year life, The Quarterly was a controversial publication. Parents, politicians and conservative-types didn’t appreciate its no-holds-barred approach to rampant fucking, and they could not, for the life of them, understand how such an adult magazine was making its way into the hands of their precious teens (who were probably jacking off to dad’s Playboys long before the Quarterly came along, but I digress). There was approximately one year — 1997 — where the amount of people it pissed off stayed below a critical mass, but after a certain somebody published a story that vaguely suggested underage kids drink, it was off to the races.

Abadsidis: We got in our fair share of trouble with Christian groups and concerned parents right off the bat. Let’s take one of the earlier issues — I believe it was Summer of 1998. It was my story. Basically, I suggested that people could do better than beer and that they should “indulge in some creative drinking.” There was one drink I made up called the “Brain Hemorrhage” and a few others you could play a drinking game with. We also included a spinner insert people could cut out.

None of it had anything to do with driving, of course, but the issue was called “On the Road.” It was a sort of beat-focused, Jack Kerouac thing, so some people interpreted that as us promoting drunk driving (though we did nothing of the sort). Also, the kid on the cover was underage. He was 16, if I remember correctly. Mothers Against Drunk Driving (MADD) didn’t like that.

Karolyn Nunnallee, vice president of public policy for MADD: We had been really focused on underage drinking and had been instrumental in getting the country’s legal drinking age raised to 21. Then Abercrombie & Fitch comes out with this weird magazine that basically said, “Don’t go back to college drinking the usual beer. We’re going to show you a new way to drink.”

Not only did they have this drinking game, but they had recipes for these mixed drinks for young people to partake in. I was like, “Abercrombie & Fitch? Aren’t they in the clothing business?” What in the world were they doing? I mean, they were a high-end brand, not Walmart. Why would they take their focus off of clothing and put it toward alcohol? Were their clothes not good enough that year or something?

Needless to say, we weren’t happy with them. Curse words were handed out. We sent a letter to them and started a whole media campaign about it. We went on as many news media outlets as we possibly could with the story of how incensed we were.

Abadsidis: I was sure I was going to get fired over that. We had to remove the page with the spinner out of every single issue across the country. We apologized, of course, but it ended up backfiring against the protesters — that incident gave us so much publicity. It put us on the map. It also made us a target for conservative types. They hated us. After MADD, boycotts of Abercrombie started flaring up all over the place. That’s around the time we hired Hampton to do PR.

Carney: It was my job, at the time, to defend the brand. I’d go on talk shows like Entertainment Tonight or Today Show and explain away our latest controversy (there were a lot). It wasn’t hard, actually; each time, I’d give them what was more or less my go-to response: “It’s a beautiful publication intended for college-aged kids.” And that was the truth! It was way ahead of its time and was absolutely meant for people 18 and up.

Though not everyone saw it that way. The sex and nudity really got to people. A lot of them definitely thought we were making porn. That was the constant complaint: We were deliberately putting porn in the hands of young kids.

Lever: The Quarterly featured about the same level of nudity as a European yogurt commercial. Which is to say, a lot. It was a “clothing catalog” with almost no clothing. Of course [American] people thought it was pornographic!

Carney: Okay, sure — there were photos of like, six girls in bed with one guy and more than a few spreads that enthusiastically suggested naked non-monogamy — but it wasn’t porn. It was tasteful. And let me tell you — nothing we had in there was surprising to kids.

Abadsidis: The models ranged from 16 to 20. It was erotic. It was art. I don’t think there’s anything pornographic about the Quarterly unless you think that nudity, in and of itself, is pornographic.

Illinois Lieutenant Governor Corinne Wood did, apparently. In 1999, she called for a boycott of Abercrombie & Fitch because its “Naughty or Nice” holiday issue “contained nudity” and “even an interview with a porn star.” That porn star was none other than Jenna Jameson, who at the time was well on her way to becoming a household name. A so-called “child prodigy” occupied the neighboring page, sparking accusations that the Quarterly somehow intended to connect children to porn.

A cartoon of Mr. and Mrs. Claus experimenting with S&M across from the statement “Sometimes it’s good to be bad” didn’t help, nor did the “sexpert” who offered advice on “sex for three” and told readers that going down on each other in a movie theater was acceptable “just so long as you do not disturb those around you.”

The Illinois Coalition of Sexual Assault joined Wood’s boycott. Later that year, Michigan attorney general (and eventual governor) Jennifer Granholm sent a letter to Abercrombie complaining that the “Naughty or Nice” issue contained sexual material that couldn’t be distributed to minors under state law.

Carney: There were four states that tried to ban us after that. I remember Granholm. She was my arch-nemesis at the time — we really got into it. I respected where she was coming from, of course, but our whole thing was that we weren’t showing anything that wasn’t actually happening on college campuses. And I’d already made it pretty clear to the press that the magazine wasn’t for minors.

Also, it’s not like we were the only magazine talking about or showing sex. You could find all the exact same stuff in Cosmo or Playboy — it’s just that we were a clothing brand, and one whose major customer base just so happened to be teens and young adults. No one expected that from us. Brands weren’t “supposed” to be talking about sex period, let alone to teens and young adults. But we took it upon ourselves to pioneer a more open, honest view of it. That’s the wrinkle that made it so interesting.

We did come to an agreement with Granholm. We decided to wrap the magazine in plastic and make it available for purchase only to those over 18, that way, it’d be even more clear that we weren’t “selling porn to the underage.”

Kon: I believe it was one of the few times the company acquiesced.

Collins: Other than that, don’t remember getting any instruction from Savas, Mike or Sam to tone it down. It was kind of mutually assumed that we weren’t going to apologize for the sexual nature of our content. We knew we had to keep things sexy, as it were — that was our whole thing.

We weren’t deliberately trying to piss off people, but we were trying to push the envelope, and there was definitely an element of deliberate trolling of conservatives and Christian groups. It was a good thing if we pissed them off. It created the controversy that made the brand seem edgy and dangerous, which is what you want if you’re trying to appeal to young people.

Carney: We were also just showing real things that happened at college. And as anyone who’s been to college knows, it’s not just about reading and writing papers. It’s also about sex. Not only that, of course, but we’re sexual beings. We respond to images that are sexual. We were trying to take the stigma away from that and acknowledge that it’s not a bad thing to do.

But no matter how clear we made it, our stance on sex polarized people more and more. I could tell, because almost as soon as I started speaking on behalf of the magazine, strange things started to happen to me. I got stalkers. People left me messages saying I was going to hell and I’d have no afterlife. I got hate mail to my house. One person left a package containing their dirty, stained underwear at the front door of my apartment with a note saying they’d be “coming by later” to “talk to me about it.” I had to call the police on that one.

I was the face of the publication, so I got the vast majority of the harassment. But I didn’t mind. It was my job to take the fall, and I heard and respected every single person’s complaint and talked to them about it. Plus, for every message I got banishing me to hell, I got another from a journalist or a fan begging me to save a copy for them. People collected them. They really loved it, precisely because it was so sexual.

Abadsidis: Mike didn’t flinch about any of this stuff. He wanted to defend it because he could see it was working. We weren’t about to tone anything down (at the time).

Flash-forward to June 2001. The Twin Towers are still standing tall, tips are being frosted and Apple has just unleashed iTunes onto an unsuspecting populace. A&F Quarterly, now in its fourth year, is in hot water once again. Having survived a number of boycotts, lawsuits and controversies since its inception, it’s now in the midst of weathering another minor national conniption over its use of nudity.

Jeannine Stein, describing the Summer 2001 issue in an excerpt from a Los Angeles Times article called “Nudity? A&F Quarterly Has It Covered”: [It’s] explicit in ways that most catalogs and fashion magazines are not, and its use of male nudity is uncommon among general-interest publications. It features 280 pages of young, attractive men and women alone and together, in serious, romantic, sexual and party modes, wearing lots of A&F clothes, some A&F clothes and sometimes no clothes at all. Among the coffee-table book-ish photos by Bruce Weber is a man, covered only by a towel, surrounded by five women; a woman at the beach reclining body-to-body with three men; a back view of a naked man getting into a helicopter (we haven’t quite figured that one out yet); and a few topless females.

There are many naked butts and breasts.

Abadsidis: We also had photos of nude women in a fountain — which were inspired by Katharine Hepburn skinny-dipping at Bryn Mawr College — and a whole set dedicated to the Berkeley student that spent a day naked in class. It was par for the course for us, but even though we’d done the whole shrink-wrap and over-18 thing, people still felt it was too sexual for branded content.

In response, an unexpected alliance formed between cultural conservatives and anti-porn feminists to boycott Abercrombie & Fitch over the Summer 2001 issue of A&F Quarterly. According to Wikipedia, the offending issue included “photographs of naked or near-naked young people frolicking on the beach,” “top-naked young women and rear-naked young men on top of each other” and an “interview with porn star Ron Jeremy, who discussed performing oral sex on himself and using a dildo cast from his own penis.” Once again, Wood was at the helm.

David Crary, journalist, excerpt from a 2001 Associated Press article: Illinois Lt. Gov. Corinne Wood — a Republican who has been sparring with A&F since 1999 — announced the boycott campaign last week in Chicago. She has recruited a diverse mix of supporters more familiar with facing off against each other than with working together.

Wood, writing on her website in 2001: A&F is glamorizing indiscriminate sexual behavior that unsophisticated teenagers are not possibly equipped to weigh against the dangers of date rape, unplanned pregnancies and sexually transmitted disease.

Michelle Dewlen, president of the Chicago chapter of the National Organization for Women, speaking at one of Woods’ press conferences in 2001: It’s not a catalog. It’s a soft porn magazine.

Rev. Bob Vanden Bosch, head of Concerned Christian Americans, as quoted by the AP: It’s very important for people to get involved. The exploitation of sex and young people in A&F’s catalog isn’t only atrocious but also a psychological molestation of their teenage customers.

Quart: It was predatory in a few ways, really. One was that it confused the corporate identity of Abercrombie and the advertising with the editorial. It preyed on young consumers not understanding the difference between editorial content and sales content. Back then it led, I saw, to a way that girls were objectifying themselves and commodifying themselves. It ultimately led to boys also objectifying themselves and commodifying themselves — not to the same extent, but far more than they were when I started reporting Branded a little more than two decades ago.

I have the stats on the male body image dysmorphia at the time in Branded (which has only worsened). Then, male body shaming and “manorexia” was on the rise, for the first time on a mass scale. It couldn’t help for the most popular brand at the time to have a dedicated giant glossy magazine filled with pictures of male teenagers with zero body fat half undressed.

Abadsidis: I mean, sure, as much as any advertising does. It wasn’t like we were leading that charge. Any effect on self-image was certainly unintentional, but I do think it did make people want to be athletic. You definitely saw a lot of guys trying to look like that during that period, especially as time went on. If you look at the first few issues, the guys aren’t that built. Ashton Kutcher was actually in the second one — that was his first big break — and they get increasingly more cut from there. That whole era is when men’s body issues started to come out.

Lever: I’d also submit that all this was controversial because it was pre-internet. The internet mainstreamed sexual content in a way that makes A&F or other “scandalous” ad campaigns (like the 2003 Gucci ad with the model’s pubes shaved into the shape of a G) seem quaint, even obsolete. Like, do you remember that Eckhaus Latta ad a few years ago that scandalized people for five minutes because it showed people having real (albeit pixelated) sex? Neither does anyone else.

SLAVOJ ŽIŽEK TEACHES SEX ED

Always filled with philosophy, social theory and intellectually minded topics that likely soared over the heads of most Abercrombie consumers, the Quarterly outdid itself in the Fall of 2003 with its penultimate issue. A gorgeous romp of summer-spirited abandon accompanied by some delightfully incoherent, Dada-like musings from Slovenian philosopher Slavoj Žižek, it connected a “back-to-school” theme with a pretty clear directive to fuck. Yet, the information it presented was actually rather safe and tame, a reality which confused and irritated Quarterly staff. Their content was legit, so why was everyone up in arms?

Abadsidis: The “Sex Ed” issue was the second to last one that we did. It got some of the most criticism, and was supposedly the reason everything was finished. I literally had stuff in there cited straight from the University of Michigan’s freshman student handbook on sexual conduct, and it still pissed people off! Then, of course, there was Žižek.

Lever: Žižek identifies as a radical leftist. He’s very famous for his work on cultural theory and critical theory. He analyzes all kinds of topics in his signature, impenetrable — but also approachable — style. And when I think of him, I think of his very distinctive manner of speaking, that some people have described as being on cocaine constantly. But he’s definitely kind of a cult figure, a favorite of people who consider themselves highbrow, but also fun.

He’s really touted as the greatest anti-capitalist of our time, and yet, here he was, “sexually educating” the mean girls and boys of your high school, in a brand catalog whose entire goal was to ensnare young people for the purpose of selling them distressed jeans.

According to the magazine’s foreword, the editor wrote to Žižek and said this: “Dear Slavoj, enclosed please find the images for our back to school issue. We’ve never had a philosopher write the text for our images before, so write what you like. We’re looking for that Karl Marx meets Groucho Marx thing you do so well. Thanks, Savas.”

Abadsidis: I love Slavoj. He was friends with one of my professors from school. He only had 24 hours to write this, so we actually sent someone to London where he was to drop off the images we wanted him to write text for. They hung out for a day and then flew back with what he’d written.

Lever: It was basically a series of insane, absurdist ramblings pasted over really hot naked people.

Žižek, excerpt from A&F Quarterly’s 2003 Sex Ed issue: Back to school thus means forget the stupid spontaneous pleasures of summer sports, of reading books, watching movies and listening to music. Pull yourself together and learn sex.

Lever: I mean, that’s like the first episode of every teen TV show, where these three nerdy boys start high school and they’re like, “Okay, we’re going to be cool this year guys. We’re going to lose our virginities.” It’s very formulaic. But there’s more.

Žižek: The only successful sexual relationship occurs when the fantasies of the two partners overlap. If the man fantasizes that making love is like riding a bike and the woman wants to be penetrated by a stud, then what truly goes on while they make love is that a horse is riding a bike… with a fantasy like that, who needs a personality?

Lever: The “go learn sex at school” part really struck a nerve with conservatives. But I don’t think it was that transgressive. Fourteen-year-olds are receiving messages to have sex all the time — what did it matter if some Eastern European anti-capitalist was hitting them over the head with it through the pages of a polo shirt advert?

Abadsidis: Fox News got involved, if I remember correctly. That was one of the few times I actually got pissed off about how an issue was being covered. I mean, the information in there was handed out to students by an actual university. Half the issue was quotes from this really influential philosopher. But for some reason, people really took offense to the language of it. That whole year [2003] was just a bad one for us.

THE LAST HORNY CHRISTMAS

For its final trick, the Quarterly released a holiday issue featuring 280 pages of “moose, ice hockey, chivalry, group sex and more.” It had oral sex, group sex, sex in a river, Christmas sex and pretty much every other type of sex you could think of, all which followed an earnest letter from Abadsidis which read: “We don’t want much this year, but in keeping with the spirit, we’d like to ask forgiveness from some of the people we’ve offended over the years. If you’d be so kind, please offer our apologies to the following: the Catholic League, former Lt. Governor Corrine Wood of Illinois, the Mexican American Legal Defense and Education Fund, the Stanford University Asian American Association, N.O.W.”

But the issue didn’t really hit. By fall 2003, Abercrombie was involved in a number of lawsuits and protests related to exclusion and discrimination, which left people cold despite the inviting warmth of a crackling, fireside circle jerk (a Weber offering which, I’m told, can be found on page 88 of the final issue).

Cole Kazdin, journalist, writing in a 2003 Slate article called “Have Yourself a Horny Little Christmas”: The challenge for me, when masturbating with my friends to the nubile nudies in the Abercrombie & Fitch catalog, is trying not to think about serious things like racial diversity; it tends to kill the mood. But because most of the models in the catalog are white and because a lawsuit has been filed against the clothing retailer for allegedly discriminating against a Black woman who applied for a job at the store, it’s hard for the issue not to rear its nonsexy head. [In 2004, Abercrombie also agreed to pay $40 million to settle a lawsuit that accused the company of promoting whites over Latino, Black, Asian-American and female applicants.]

Collins: As a brand, Abercrombie did a lot of things that were quite gross. I’m sure you remember when they came out with these T-shirts with these racist stereotype characters on them. You would just see it in the catalog and just be like, “Jesus Christ.” It was awful and stupid and self-defeating, just tone deaf. And we just couldn’t figure out how no one at the company saw the problem with it.

Stagg, excerpt from Sleeveless: Kids in my high school wore shirts that read, “Wok-n-Bowl” and “Wong Brothers Laundry Service: Two Wongs Can Make It White,” accompanied by cross-eyed propaganda-style cartoons. If you weren’t part of the in-crowd (and white), A&F was oppressive. Non-jocks made their own anti-A&F T-shirts, using the brand as a catchall for exclusionary, competitive behavior and old-fashioned bullying.

Carney: That stuff was indefensible, really. Those were the darkest days of my job — listening to calls and reading letters about how offensive those shirts were. Even though the Quarterly was quite separate from the brand and we had no influence over what they did or what clothes they designed, we did still have to print their stuff at the back of the magazine. It was pretty uncomfortable.

Stagg: By 2006, Mike Jeffries’ most controversial public statement on sex appeal was really just saying what we were all thinking: “Are we exclusionary? Absolutely.” Those remarks were followed by lawsuit after lawsuit, mostly involving staffing discrimination. An announcement about the store refusing to carry anything over a size 10 reportedly marked a noticeable decrease in sales.

Abadsidis: There were a lot of underlying problems at the company. The amount of negative press Abercrombie was getting was getting silly. No matter what we did, we’d end up in the news, especially if it was related to the Quarterly. After so many bad news incidents, it just felt done, like its moment had passed. It was bound to crash at some point.

Gina Piccalo, excerpt from the Los Angeles Times: Clothing retailer Abercrombie & Fitch has pulled its controversial in-store catalogs after outraged parents, conservative Christian groups and child advocates threatened a boycott over material they said was pornographic. However, a company spokesman said the move had nothing to do with the public outcry. The catalogs were pulled to make room near cash registers for a new Abercrombie & Fitch fragrance.

Abadsidis: People like to think that the boycotts and Christian protests had something to do with it, but that wasn’t the case at all. By 2003, Abercrombie’s stock was low — something to do with ordering too much denim. The store was having negative sales for the first time. There was the line in the New York Times, who covered our demise, that Mike was “bored” with it.

Collins: We had no warning. We were all there one day, and the next, we were gone.

Lever: The Quarterly was a relic of a different time. I feel like it could never have been made after 2008 for so many reasons — economic, and cultural and political. It would just never fly. It was made before feminism pervaded everything, at a time where you could be completely flagrant about gross patriarchal shit and still get away with it.

It was kind of like this last gasp of a certain conception of what’s desirable — a very hegemonic coolness exemplified by white Ivy League frat kids who got fucked up the night before their philosophy class. That doesn’t have much currency anymore. Abercrombie kept that image on life support until its last gasp.

Now, 20 years later, what’s cool is not that. What’s cool is to have depression and ADD. The ideal is out. The real is in. And the Quarterly, having always existed in the liminal space between, is neither here nor there.

EPILOGUE

In 2008, Abercrombie resurrected the Quarterly in the U.K. for a limited-run special edition to celebrate the success of its European stores. The original team was reunited — Abadsidis, Shahid and Weber — with the hopes that Britain’s more “open-minded approach to culture and creativity” would provide a welcoming substrate on which to re-grow their original ideas of sexual liberation. The issue, “Return to Paradise,” was “more mature” than its American cousin. It was well-received — aside from the usual protests about sex and nudity — but it wasn’t continued.

Two years later, in 2010, the Quarterly was revived again, this time as a promotional element for Abercrombie’s Back-to-School 2010 marketing campaign, which bore the unfortunate title of “Screen Test.” The lead story Abercrombie put out on its website sounded like a cross between American Idol and a gay porn shot: “The staff of A&F Studios opens up to editorial to explain the steps the division takes to find new, young, hot boys. The cattle-call approach to herd young talent ends with the best of the beefcake earning a screen test that ‘could be the flint to spark the trip to the star.’”

Bruce Weber would be shooting, of course. This would become especially ominous after he was accused of a series of casting-couch style sexual assaults by 15 male models beginning in 2017. According to the accusations, he subjected them to sexually manipulative “breathing exercises” and inappropriate touching, insinuating that he could help their careers if they complied.

Arick Fudali, a lawyer at the Bloom Firm, which represents five of Weber’s alleged victims, declined to confirm or deny whether any of the alleged assaults happened on a Quarterly shoot. If they did, they’re not prosecutable as sexual assaults in New York. Because the states’s statute of limitations on reporting rape is only three years, anything that happened during the Quarterly’s run wouldn’t count toward a sexual assault charge (unless a minor was involved, which Fudali also declined to confirm).

No one I spoke with for this story remembers seeing, hearing or experiencing anything like what the allegations against Weber describe, but some expressed concern over how they might affect the legacy the Quarterly leaves behind. “The accusations are pretty grim,” Collins told me. “You feel for the people who are put in that position. People had power over them. It just makes you think, ‘Was any of this worth it?’ Not really, if people were getting hurt.”

As such, it’s difficult to conclude with definitive sign-off about the Quarterly’s legacy. Either it was a bastion of progressive and transversive sexuality that simultaneously trolled and nourished the very audience it sought to mine, or it was the product of darkness and pain. Either way, Sockel sums it up just right: “The Quarterly was discontinued in 2003, after the American Decency Association boycotted photos of doe-eyed bare-assed jocks in prairies and glens,” he wrote in his recollection. “It was nice while it lasted.”

42 notes

·

View notes

Photo

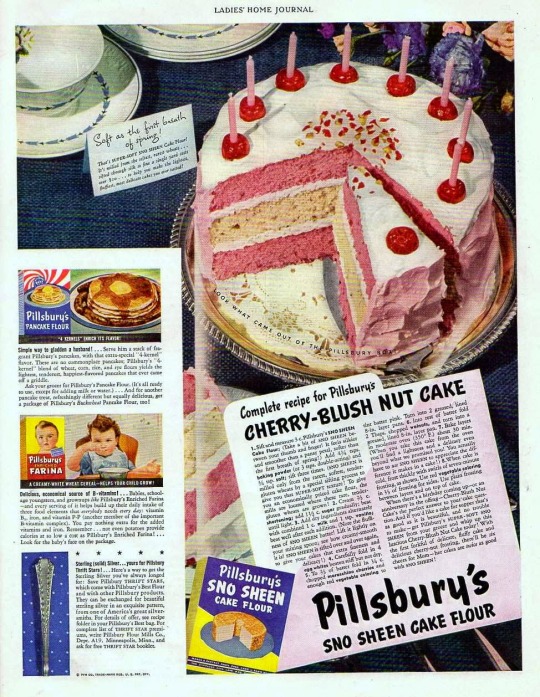

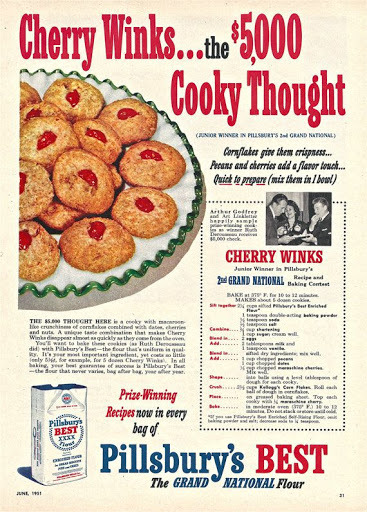

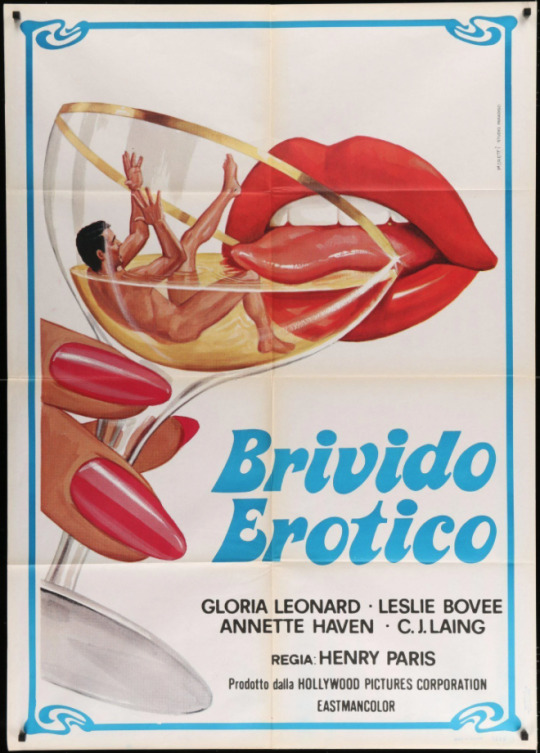

HOW THE MARASCHINO CHERRY BECAME A COMFORTINGLY TRASHY AMERICAN ICON

Just when did the syrupy, lipstick-red lynchpin of ice cream sundaes, 1970s fruit salads and throwback cocktails conquer the world (and your grandparents’ home bar)?

The cocktail cherry may be small, but it looms like a fiery red planet over the modern history of eating and drinking. Look, there it is, bobbing around in the rust-brown murk of a Manhattan; and, hey, there it is again nestled in the snowy peak of an ice cream sundae, lurking in the syrup-soaked folds of an upended can of fruit salad, or in your parent’s drinking cabinet, languishing in a sticky jar first opened at the dawn of the Clinton administration.

For more than 100 years it’s been the Zelig of the culinary world, beaming out from multiple places it probably shouldn’t be, inviting you to spear one with a cocktail stick, bite down and let your mouth flood with the unmistakable taste of… well, what exactly?

Not actual, fresh cherries, that’s for certain. No, the taste of a cocktail, glacé or ersatz maraschino cherry has nothing to do with the luscious, grape-like subtlety of real stone-fruit. Its impact on the palate — almonds and preservatives and a great, hallucinatory wash of artificial sweetness — is the flavor profile of a cherry as described by a drunken child. Something that, even way back in 1911, was railed against in a New York Times editorial as “a tasteless, indigestible thing, originally, to be sure, a fruit of the cherry tree, but toughened and reduced to the semblance of a formless, gummy lump by long imprisonment in a bottle filled with so-called maraschino.”

And yet, even though this resistance to the gloopy, synthesized commercialism those little red globules represent is at least a century old, the cocktail cherry abides as a cultural artifact. Not just in the post-Mad Men context of master mixologists hoarding artisanal Luxardo cherries or producing their own housemade varieties, but in studiedly kitsch, revivalist dessert parlors like New York’s Morgenstern’s Finest Ice Cream; and even, scattered throughout Quentin Tarantino’s Once Upon A Time… in Hollywood, garnishing the industrial-strength whiskey sours of one Rick “Fucking” Dalton.

“When you see a bright red one now, it’s like a bartender with a waxed moustache and sleeve garters,” notes Jared Brown, drinks historian and master distiller with venerated British gin brand Sipsmith. “It’s no longer just itself. It’s nostalgia and irony and humor.”

So how does something so ridiculous and occasionally reviled come to have such durable appeal? How the hell are they even made? And what, exactly, do bitter food standardization wars, embalming fluids and carcinogenic food dyes have to do with it?

Well, pour yourself a stiff Mai Tai, crown it with what may be your final ever cocktail cherry, and let’s chart the turbulent life, near-death and eventual resurrection of a near-indestructible American icon.

As with most convenience foods, the cocktail cherry story starts out innocently enough. Cherries stretch back to the prehistory of Europe and West Asia, and pretty much since that time, they’ve been notorious as the frail divas of the produce aisle — difficult to transport, susceptible to bruising and known to liquefy without refrigeration. And so, innovative orchard owners in the early 1800s — most notably the Croatian-born, Italian-based Luxardo family — started preserving at-their-peak cherries, both as an alcoholic liqueur and steeped in a boozy brine made up of mulched cherries, pits and sugar.

This was the Big Bang that gave us the maraschino, named for the sour, Marasca cherry variety that Luxardo made their own. It wasn’t long until these pickled fruits were infiltrating the U.S. as part of the wider mania for cocktails in the mid-to-late 19th century. (The original 1888 recipe for the martini, as Brown notes, called for a “cherry rather than an olive.”) But soon, that original, burgundy-hued Luxardo maraschino was joined by a whole Rothko color wheel of lurid U.S.-made knock-offs, soaked in cheaper preserving syrups.

One reason for this was pure cosmetics. “The first taste is with the eye, and in the days before social media, the maraschino cherry offered a huge visual bounce,” notes Brown. “Think of it resting in the brown tone of a Manhattan — it’s like a bright red beacon in the drink. [And so,] there was a need to get it as brightly colored as possible.”

Yet it’s also notable that the maraschino cherry’s turn-of-the-century ascendancy also coincided with the wider vogue for lab-made dyes, flavorings and additives that flourished in the pre-FDA era. (Relevant: This was also a time when, at the behest of nervous dairy farmers, margarine had to literally be dyed pink in some states to broadcast the fact it wasn’t butter.) “For many years, I’ve asked audiences at tasting events what maraschino cherries, grenadine and sloe gin have in common,” says Brown. “And the answer, of course, is nothing. Nothing! And yet, go back to my childhood and they were all the same color and flavor because they came from the same lab.”

Throw in the arrival of Prohibition in 1920, and the fact it meant fruit could no longer be preserved in alcohol, and other brining methods needed to be found. It was a team of Oregon-based scientists who, after more than five years of experimentation, realized that calcium salts could preserve the Northwest’s seasonal glut of fresh cherries, and also help them retain their firmness. What’s more, in the 1930s, this same team realized that if you bleached the cherries and then dyed them red (or green, or even, occasionally, electric blue) the vivid pop of color would be even more pronounced. At this point, the American “maraschino” — leached of its natural color, embalmed in synthetic preservative and flavored with almond-derived benzaldehyde — had mutated into something only tenuously related to its European forbearer.

The original maraschino farmers in Italy were — if you can believe this — not crazy about American producers using their name to hawk cloying, cherry-shaped candies the color of antifreeze. But by 1940, they had lost a long-stewing food standardization battle, when the FDA decreed that the name “maraschino” had now evolved beyond its original meaning and, to most Americans, meant the artificially flavored neon red scourge of the Luxardo family.

And so, in the wake of World War II, the cocktail cherry’s cultural dominance truly began; slotting into an additive-laced mid-century food landscape, they gleamed from Betty Crocker cake recipes, adorned every other drink at a newly established 1950s Tiki bar chain called Trader Vic’s, and even, come 1978, gave their name to a hardcore adult film called Maraschino Cherry. “I remember adoring them,” says Brown, recalling his 1970s childhood in upstate New York. “There was nothing better, when we were out at a restaurant, than getting a cherry on a little plastic cocktail sword.”

If anything they were even more adored in the U.K., where a collective, post-rationing proclivity for all things sweet only added to their appeal. Eccentric TV chef Fanny Cradock would place them on the top of troublingly phallic “banana candle” party concoctions, and in Only Fools and Horses — a beloved, long-running BBC One sitcom about a family of luckless grifters living in South London — it became synonymous with main character Del Boy and his fondness for gaudy drinks that represented a tacky sort of sophistication. Even when I was growing up in 1990s London, my parents — first-generation Nigerians who rarely drank — would always have a glowing container of what we knew as glacé cherries beside a long-opened bottle of brandy.

“You can’t underestimate the power of a good garnish,” laughs Alice Lascelles, drinks writer and author of Ten Cocktails: The Art of Convivial Drinking. “That Day-Glo cherry is something I associate very strongly with childhood and the idea of a grown-up drink, a celebratory drink.” This mixture of childishness — of innocence — and a more adult glamor seems to be at the heart of the cocktail cherry’s appeal throughout this period toward the end of the last century; they’re fruit with all the subtlety and unpredictability chemically extracted, an unapologetic hit of trashiness that appeals to both Chuck E. Cheese birthday party attendees and the kind of chain-smoking bar flies we all sat two stools from long before social-distancing measures required it.

But, of course, the cocktail cherry party came to an abrupt halt later in the 1980s. Partly, this may have been lingering scares over the occasional use of Red Dye Number 4 — a chemical colorant with some links to cancer in animal trials — in some preserved cherries, permitted because they were deemed to be “decorative” rather than a foodstuff. Also: There were unfounded rumors about formaldehyde being used as a preservative which, perhaps fittingly, just wouldn’t die.

Mostly, though, their waning was linked to the demise of the movement that first popularized them in the U.S. “The maraschino cherry collapsed precipitously along with the collapse of cocktails,” says Brown. “Suddenly, you weren’t finding anyone over the age of 10 lunging toward maraschino cherries, and what happened was people discovered wine, which eventually went into craft beer.”

At that point, in terms of the popular consciousness, cocktail cherries were mostly glimpsed at the fringes of culture, or within insalubrious bars with “C” hygiene ratings tacked to their windows. Then, inevitably, as the cocktail revival of the mid-2000s began in coastal cities, sailor-tattooed mixologists started looking into what preceded the neon cocktail cherries of their youth, and eventually rediscovered Luxardo’s original, burgundy-colored and naturally sweetened maraschinos.

“I remember I’d race [Milk & Honey founder and bartender] Sasha Petrosky and Audrey Saunders [of the Pegu Club] to a place called Dean & Deluca because it was the only place you could buy Luxardo maraschino cherries in New York,” recalls Brown about the frenzy during the craft cocktail boom. “It didn’t matter which one of us got there first; we would end up [dividing] them out until the next shipment.” Now, Brown reports, Luxardo is sending “palette-loads a week over” for import and he himself preserves around 200 jars of maraschino-style cherries a year to sell from his home in the English countryside. In 2017, Luxardo planted 2,000 new Marasca cherry trees in Northern Italy — taking their total to 30,000 — just to keep pace with demand.

The pendulum, after all those years of traffic light-red candied cherries, has swung back to something purer again. Yet, interestingly, the unnatural cocktail varieties haven’t disappeared. They’ve had their own rebirth, whether crowning old school cocktails at acclaimed, 1960s-inspired Detroit bar Hammer and Nail, or clogging social media feeds as part of author Anna Pallai’s Twitter account-turned-campy-coffee-table-hit 70s Dinner Party. “There’s a definite trend for kitsch that’s brought them back,” says Lascelles. “Instagram has helped as well, because they really pop in a picture.”

It makes sense that the current, extremely online moment — where almost everything can be both completely sincere and larded in multiple confusing layers of irony — would be the time when both these diametrically opposed approaches to cherry preservation would find room to flourish. They are, as Brown notes, “jubilant and ebullient at a time when humor and fun is something we are all desperate for.” It seems as plain as the unearthly red glow, beaming from the bottom of a filled coupe glass in the corner. Like that opened jar in your parents’ home bar, the cocktail cherry isn’t going anywhere.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

HOW FLAMIN’ HOT CHEETOS BECAME THE MOST AMERICAN SNACK

The most inspiring biopic to come out of Hollywood in the next few years won’t be about a politician or war hero. It won’t follow the life of a tortured artist or scientist. It definitely won’t be the Scorsese film where Jamie Foxx plays Mike Tyson. No, the flick that’s destined to nail us in the feels with a true-to-life story is Flamin’ Hot, a Fox Searchlight project based on the American dream of one Richard Montañez, the genius who blessed the world with Flamin’ Hot Cheetos — a snack we could no longer go without.

Montañez, if you didn’t know, immigrated to California from Mexico as a child and grew up helping to support his family by picking grapes. He dropped out of high school in the mid-1970s and took a job as janitor in the Frito-Lay factory in Rancho Cucamonga. As legend has it, an assembly line glitch one day produced Cheetos without their distinctive orange dust, so Montañez took some home to coat with chili powder, à la elote, or Mexican street corn. The experiment was so successful that he bought a $3 tie and presented his new recipe to executives.