Text

(preview only*)

The audience for artists' moving image practices has grown extensively in recent years. Of course, the Internet has played a huge role in this. An ever-growing part of this audience is using the video-sharing platform Vimeo. This website was founded in 2004, just a year before YouTube, and since the beginning its peculiarity has been the support of high-definition videos. Compared to the Google-owned colossus, Vimeo represents a smaller presence on the Internet, the Alexa rank being 2 for YouTube and 131 for Vimeo.

For a lot of reasons which I won't discuss here, Vimeo is mostly used by professionals such as filmmakers, animators, motion graphic designers, but also by private companies and institutions, most notably the White House under the Obama administration. Artists working with moving image use Vimeo's services to upload their work, password-protect it and share it with festival programmers, curators and other professionals. They also publish teasers, trailers and excerpts of their works.

I can't tell you when (I wish I could), but out of this standard practice another quickly came: a lot of these artists started taking the password-protection off their works. By doing this, of course, the artists aim to reach a larger number of potential viewers. But this practice is linked to two common (and closely-related) film festival policies: in order to be considered for selection, the work submitted needs to be recent (with the limit usually being set as two years since its completion) and not publicly available online (that is, password-protected). For this reason, after their two-year festival tour, a lot of experimental films and videos were being set free from their passwords and released into the wild.

In this framework, one should also mention other interesting practices: when artists don't care about festivals and make their new works accessible to everyone, or when they finally publish their older works (sometimes remastered, sometimes never before released). There are also artists who come from the contemporary art world, whose works are represented and sold by galleries and shown in contexts other than those of film festivals. They too, for one reason or the other, are now playing the game of free online availability.

With an increasing number of interesting works made officially and freely available, a niche audience was born. One that is potentially growing—because the general interest in artists' moving image is visibly growing, but also because, within the demographics of artists' moving image fans, not everybody can easily attend festivals and visit galleries. Some live far from big cities, some can't move, some can't travel, some are still too young to travel. Not everyone has access to closed, selective online communities such as Karagarga. And I could go on with these examples for a while.

I recognise myself as part of that audience. As a fan, it's been a fascinating experience since I started paying attention to what was being made available online by the artists I liked. Between 2013 and 2014, I happily enjoyed the works of Portuguese artists João Maria Gusmão + Pedro Paiva both in physical exhibitions (at the Venice Biennale and at the IAC in Villeurbanne) and online through their Vimeo account, where one can watch a selection of digitised versions of their already iconic slow motion 16mm films.

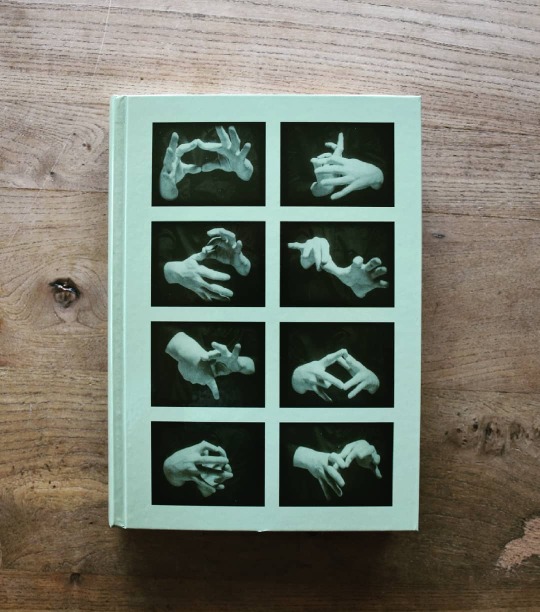

In the winter of 2016, I was discovering the contemporary North-American scene. Through blogs, newsletters and social media, names like Robert Todd, Margaret Rorison, Stephen Broomer, Dan Browne and Mary Helena Clark were popping up and there they were with their accounts full of previous works available to watch. I remember sitting at my desk, watching Mary Helena Clark's astonishing Palms (which, at the time, was the most recent work she had made available in its entirety) and feeling lucky to get to see such revealing work. It felt like a gift.

Whether it be purely strategical or emotional, releasing a piece of work online can be the easiest or the toughest decision to make for an artist. It can be the result of (quite a few) compromises: selecting only a few pieces to release, making them available for a limited time only, going back to password-protection because of the renewed interest of festivals in a certain piece. For a distributed or gallery-represented artist, the choice can be quite difficult. After all, we have to consider that nineteen years of Web 2.0 have taught us to use and share online contents in ways that can clearly clash with the traditional sense of authorship. In the case of this niche, it has become common practice to hold public screenings of pieces found on video-sharing platforms without asking for permission from the author. Surprisingly, this happens in contexts where a wide range of authorship regulations should normally be acknowledged, including film studies classes and exhibitions (See the Abounaddara / Triennale di Milano case).

In the winter of 2016, I was thus looking for a way to give something in exchange, to contribute to such a thriving exhibition of works. My contribution ended up being the online project The Moving Image Catalog. At first I only created a Facebook page where I posted links to videos. It gradually became a curated selection of works that attempts to link artists, practices and themes, in the form of a website, with a sort of index that was going to be a perpetual work-in-progress, and various social media pages. That was my small contribution—that, and the daily romantic act of (always) barely scratching the surface of this huge collection of works.

Growing up in a small town in northern Italy in the early 2000s, with almost no galleries and only three cinemas that showed only dubbed films (one of them was torn down to build an expensive clothes shop), being interested in moving images meant having to rent DVDs and watch TV, notably the RAITRE channel. RAITRE had and still has an all-nighter film programme called FUORI ORARIO, where one can catch the latest Lav Diaz, or a De Oliveira film, or a segment from an amazing and mesmerizing film whose author you'll never know (because the programmers like the idea of not presenting the segments). As FUORI ORARIO shaped generations of film lovers, my emotional attachment to moving images was also shaped by these nightly encounters in front of a small screen and not in a traditional screening room. Today, while I do prefer galleries and screening rooms to TV and computer screens, I consider the act of watching moving image works on Vimeo to be a highly aesthetic and emotional experience.

About a year ago, I was checking the Vimeo account of an artist whose work I love and who is very popular today. Going to festivals and screenings, one gets to watch the films made by this artist. I was browsing this particular Vimeo account because the said artist's work was being gradually made available for free watching. Due to the prolific nature of this artist, I often visit this account. So, I was browsing, and I noticed a change. Placed between parentheses, a brief expression is now added at the end of each title:

(preview only*)

The asterisk directs the viewer to a disclaimer message which appears in the info section below the player. This disclaimer is addressed to professionals who intend to screen the films in public events (festivals, lectures, classes etc.). The artist asks them to contact the distributor. By doing so, the artist warns us that the Vimeo link should not be used as such for a screening. Again, the addition of the said disclaimer speaks volumes about the decisions involved for an artist when it comes to showing work online.

But let's adopt the perspective of a viewer, and not the practical purposes of the artist. Even if one understands that the disclaimer is intended for a specific category of viewers - those who use Vimeo to select works to be shown in public events - one's experience can be thoroughly modified by this indication. I consider that the sentimental experience I normally have when I watch artists' moving image works on Vimeo is not one that can be described as the “preview only” of another, possibly better, experience, such as the public projection.

Which brings me to a few questions I've been asking myself, and which I now would like to ask you:

Is there an emotional hierarchy in the aesthetic experience of watching moving images? Is this hierarchy genre-related? Should public screenings still be considered the only true experience?

Are we, as artists, paving the way towards acknowledging online audiences as audiences in their own right, and as important as the audience at public events? Or are we just riding the online wave in the sole hope of reaching more physical screening possibilities?

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

After Le Grice: on inciting a new culture and infiltrating institutions A conversation with Malcolm Le Grice, A Coruña, June 6 2019.

Prelude

In May 2016 I was in London, at the BFI, to attend a special evening of performances by Malcolm Le Grice. An event so rare that I asked myself whether that would be my first and last chance to see Le Grice performing his iconic Horror Film 1 (1971). The evening programme also comprised Threshold (1972) and After Leonardo (1973), of which you can watch below eighteen fragments:

Three years later, the curators of (S8) Mostra de Cinema Periférico proved me wrong by inviting Le Grice (now aged 79) to A Coruña for a retrospective and a master class. The intensity of the retrospective last programme – composed of Castle 1 (1966), Berlin Horse (1970), Threshold and Horror Film 1, all presented in 16mm – moved the audience, some of them broke into tears. After performing Horror Film 1, Le Grice said that it was maybe his last performance of the piece, adding "I'm actually offering it to anyone else who wants to do it. There is a person in New Zealand, a woman, who does it, and I've given her all the materials for it, and she does it occasionally. She also does it with students.". The emotions of that evening are still violently pulsating, and all I can say is: I don't want to believe you, Malcolm. You'll perform again, and we will all be grateful for that.

After his master class at Filmoteca de Galicia, I sat down with him for a short conversation on his first book, academia and more.

* * *

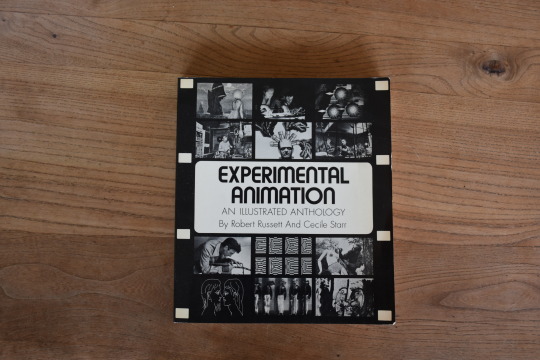

I would like to start this conversation by engaging with memory. I have with me a copy of your 1977 book Abstract Film and Beyond. Can you tell me something about the time when you were writing this?

Well, it's interesting because I was working on it for at least two years, I think, but mostly the writing was done in six months. But then nearly a year and a half was spent in editing and getting the publication done. Now, goodness, how do I get my brain back to what was going on then? First of all, I wrote the book because there were things which I didn't know. So I had to do real research into the early period of experimental cinema, which was Léger and Man Ray, and even Oskar Fischinger and Hans Richter, all of that. And not just abstract: my understanding of abstract is not the same thing as non-figurative. My understanding of abstract is when you draw out the properties and separate the properties from each other: that's abstraction. If you take the colour from the form, so you got an orange or whatever, and you take the colour away, you've got orange and you've got the form. And those are two abstractions. So, once you've abstracted, instead of putting back orange you could put back green, or blue, or whatever. That, for me, is for example what Matisse does in the Fauves. So, for me abstraction is not just about films with no representation. I took the interpretation that you could take films that had photographic images and they could still be abstract. So, Léger's Ballet mécanique, for example, is abstract.

Then, there was a polemical question as well, although it didn't play so heavily in this. A very important polemic at that time was to establish the British and the European artists in the experimental cinema, when it was completely dominated by the American. Because the Americans had a lot of developed artists, but they also had all the publicity system, they had promotion. You know, I talked about the CIA this morning, but actually, the CIA was promoting artists, as a cultural promotion. It's not true that I was cynical, because actually a lot of people involved in the CIA liked the work, they actually appreciated it. From the politics of American culture it was very important to make an establishment of the European work in a way that could be compared with (and compete with) the American work, so that polemic is in there.

I've always felt that Abstract Film and Beyond was more of an artist book than an academic one – I don't think you like the word academic. I see it as an artist book because the research you were doing, the type of questioning, has the urge of a creator, of someone who wants to understand something, reach a perspective, in order to keep creating. You've also inserted yourself, your artistic practice, in the book: you write, briefly, about your work, one can see reproductions of film strips from Little Dog for Roger and Berlin Horse, and also a picture of you performing Horror Film 1. Because of this aspect of your book, I wonder if you've ever been questioned about research rigour, in an academic context.

Not at all. I mean, there wasn't the same academic establishment then, that there is now. Now, a lot of publication is done in universities to make sure that your research rating is high. And that you could get your money for research. So it's a gain now. When I wrote this I didn't think of it being in the university at all, for me it was in the public domain, it wasn't for the university. In fact, there really wasn't any experimental film in the British universities at all, at that time. Even the art colleges, many of them didn't even offer degrees, they didn't offer a Bachelor of Arts or a Master of Arts, a lot of the art colleges simply offered diplomas, so there was no establishment of a research culture within the universities. That changed, and I was part of the change, because when I became Dean of Faculty [

at Harrow College in 1984, Ed.

] and then Head of Research [

at Central Saint Martins in 1997, Ed.

] it was at a time when first of all we established that art could be a subject for a bachelor's degree, that it could have master's degrees and that it could have doctorates. That didn't exist. By the nineties we were establishing all of that, the BAs earlier, and I was part of this because the money for teaching was going down and down, so the only way of making up the difference of the money in the university context, was to build your research funding. I got very involved, I was on the national committee for how to define research in the arts, and that committee then decided on the equivalences for research. After that, the universities that had art departments were able to apply to the government for research funding. Of course that made a big difference to the teachers mainly, because the research money went to the teachers for their research activity. Some of it went to students for PhDs, but the main amount was going to the teachers. So that didn't exist at the time this book was written. It was very naïve and very undeveloped. The awareness, the culture, was very undeveloped for experimental cinema and there was a sort of still uncertainty. The production money came from the British Film Institute or the Arts Council. The British Film Institute didn't have any understanding of experimental film at all, they brought me on to the committee of the production board of the British Film Institute [

from 1971 to 1975, Ed.

] and then I was the chair of the committee at the Arts Council, for artists' film and video [

from 1986 to 1990, Ed.

]. In that way, it was all about building up a basis for the culture.

You were creating tools for the future generations.

That's right, I don't think I'm making this up in retrospect. What I realised was that we needed a culture for this. We needed something more than individual artists trying to make films. We needed a culture. And obviously the focus for that culture, to start with, was the Arts Laboratory. It was more important than people realise. The Arts Laboratory in Drury Lane was the centre of counter-culture. But there was also the group who started the London Film-Makers' Co-op, they were all really cinéastes, not filmmakers, as far as I can recall, the only filmmaker in that group was Stephen Dwoskin. He was the only one, all the rest were all saying "Wouldn't it be nice if we had a film culture?". The London Film-Makers' Co-op was modelled completely on the New York's Film-Makers' Cooperative, but all the production idea came not from there, but from the Arts Laboratory.

In regard to building an experimental film culture, can you tell me more about the days at the Arts Laboratory?

It was me and David Curtis, we talked a lot about how to encourage and stimulate filmmaking, and David was very important in this. He dug up other artists and put on performances and various things in the Arts Lab. He was a very significant figure really, and he set a cinema up and really promoted experimental film. He and I were a lot together, it was he and I who really had the idea of a filmmakers' workshop. Then, he was always very supportive and he was working at the Arts Council as well. We were infiltrators.

You were injecting something new into the country's institutions - that were still not understanding what you were doing. Were you fully aware of the strategic possibilities given by this chance to infiltrate institutions like the BFI and the Arts Council?

There's something strange about the English: if somebody opposes, then what they try to do is not stop it but try to include it. I was a big, big critic, of the British Film Institute in relationship to contemporary and experimental cinema, so what did they do? They asked me to join the committee. So I'm infiltrating, and of course I don't say "Oh no, I'm not going to go in that committee". It's how the British at that time worked.

I would like to go back to Abstract Film and Beyond. Speaking in terms of research, of conceptual understanding: when you finished the book, do you recall of achieving something that you needed for your artistic practice?

The research and the thinking increased the intellectual content, the understanding, of what was going on. It is more analytical than it is theoretical, analysing what was going on in experimental film. I'm more of an analyst than I am a theorist. Peter Gidal is more of a theorist, I am a theorist, but mostly I'm looking at things and see how does this work, what's going on with it, what's actually happening.

Do you think that this analytical modus operandi is also reflected in your films?

I don't know, I think that's different. Again, Peter Gidal and I we've talked a lot over the years. One of the things I think we both agreed with is that none of us begin our work from theory, we always prefer a more spontaneous practice. Virtually none of the films that I made began from a theoretical position. The theory came as an analysis afterwards, by including what actually is now a very important essay, which is the Real time/space essay1. But Real time/space did not lead the work, the work led the concept. And, certainly for my part, I've always trusted an unconscious instinct as a filmmaker. Writing the book gave a stronger rationale to the work, but it didn't actually change the work. I would go and do things like Little Dog for Roger for example: you could not begin that from theory, there's no way. When I look at it, I now know that there's a common set of aesthetic notions that come from Little Dog for Roger, Birgit and Wilhelm Hein's Rohfilm and George Landow's Film in which there appear Sprocket Holes, Edge Lettering, Dirt Particles etc. When I made Little Dog for Roger I was not thinking of Rohfilm, I was not thinking about George Landow, I was making Little Dog for Roger, and I was making it in the same way I would make a painting. Only when I looked at it I would think "What's happening here? What's the difference between this and other non-materialist film practices?". It's still pretty much true that a lot of my filmmaking and videomaking comes out from the unconscious. I may have strategies of various sorts but [he pauses to think, Ed.]. There were a few films, the long feature-length films, which are Emily, Finnegans Chin and Black Bird Descending2, which address issues around narrative - they're works with a certain amount of theory-preceding-the-work, which was a bad thing. Fairly quickly after making them I said to myself: you're on the wrong track. You know, it was a big discussion going on at that time around deconstruction, narrative and feminism, with Laura Mulvey, who was a great friend of mine. Laura Mulvey and Peter Wollen shot one of their films in my kitchen.

The kitchen in Riddles of the Sphinx?

It's my kitchen in Harrow. There was a lot of that kind of cross-discussion and influence. And I was influenced by the debate about feminism, but in particular about the semiotics of cinema. But that was the only time, I think, in my filmmaking, where the theoretical got into the films ahead of the making. Also partly because I got a lot of money for those from Channel 4 and from the Arts Council, and you don't take as many risks, if you're working with a big budget. With a big budget you got a cameraman and a crew. I've looked at them recently, and they're not as bad as I think. But I realised that my earlier work was more in the right direction. So I then went back. That's when I started making short videos. I went back to saying "OK, I'm going to make short films, I'm going to respond to the material, I'm not going to take on that kind of wrong ambition".

1Malcolm Le Grice, Real time/space, Art and Artists, December 1972, pp 39-43.

2Emily - Third Party Speculation (1979), Finnegans Chin - Temporal Economy (1981) and Black Bird Descending: Tense Alignment (1977).

1 note

·

View note