Text

I have a new hobby

+fencing gesture drawings

275 notes

·

View notes

Text

It isn't the same but it is enough (x)

before y'all start coming for me, i promise eugene is alive and well

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

Harvard and Aiden from Fence by C.S Pacat and Sarah Rees Brennan! This artwork was inspired by this post by @loniereads and @engardemyheart

I saw it and just couldn’t resist. 😂

305 notes

·

View notes

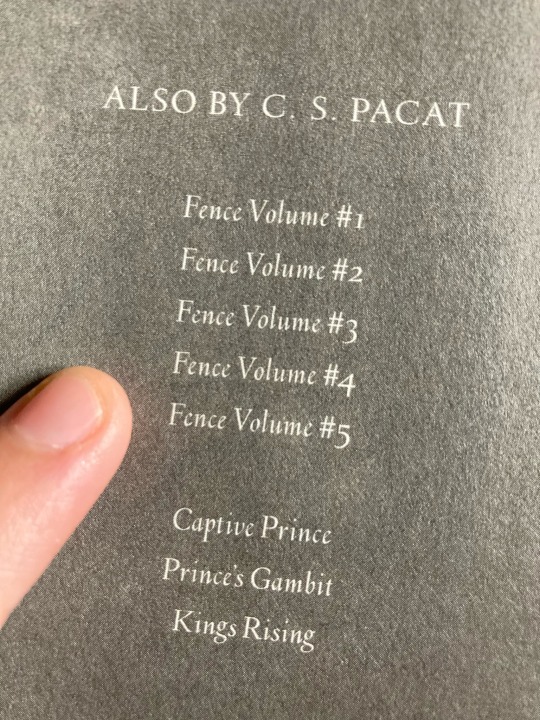

Text

so i started reading dark rise and i just realized-

where

is

it

137 notes

·

View notes

Text

happy anniversary to fence issue one release 😌🎉✨

122 notes

·

View notes

Photo

seiji katayama - golden boy

(been thinking about fence a lot recently so i drew him like those old serious portraits)

104 notes

·

View notes

Text

I’m in that place again where my love of Hot Fuzz is burning with the heat of a million suns, and it is mingling nicely with my love of Fence.

75 notes

·

View notes

Text

I looked at the panel where they shake hands after getting their fencing pins and said “but what if they kissed instead.”

Cred to Johanna the Mad

161 notes

·

View notes

Text

Day 3 of my favorite Nicholas Cox Facial Expressions

53 notes

·

View notes

Note

About your post about the bad autistic rep in the fence novels, can you tell me why it’s bad? No problem if you don’t want to, I know it’d take a lot of time and you shouldn’t have to educate other people

Hey friend! I’m always happy to talk about Fence, and honestly the only reason I didn’t expand more on this topic to begin with was because I was too low on energy/time and too high on frustration to actually collect my thoughts into a meaningful analysis. Which is why it’s taken me so long to respond to this ask.

A little disclaimer: people don’t need permission to enjoy the content they enjoy, but I do ask that they listen to autistic people on matters of autistic representation. You don’t need to be a part of a minority to spot harmful representation, but it can be less obvious to non-autistic people why Seiji’s autistic coding in the Fence novels is an ableist caricature of autistic people. Lastly, representation is a nebulous and many-layered thing, which I’ll speak more on in a moment, but it’s true that while every autistic person I’ve spoken to on the matter of Seiji’s depiction in the novels has been just as uncomfortable, upset, hurt, and angry as I am, there are sure to be those who feel seen by his characterization. I’m not saying they’re wrong, but I do think there’s an element of personal projection there—again, that’s not bad at all—but it’s worth considering, when looking at Sarah Rees Brennan’s version of Seiji, if he’s still Seiji Katayama or if he’s a blank slate you can project onto. Because there’s a distinction there and I do think it matters. But the bottom line is that I cannot speak for all autistic people, nor am I trying to. I’m just trying to explain where I’m coming from with my hurt, both personally and more objectively in terms of how it is harmful to autistic people through perpetuating stereotypes.

Let’s start with what is a stereotype? Why is it bad? If people relate to a stereotype, how can it be wrong or hurtful to have stereotypical representation? When discussing stereotypes, I always refer to the amazing words of Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie and her description of the single story. I would highly recommend you watch her TEDtalk, as it’s brilliantly, thoughtfully, and beautifully said. While the speech itself is geared toward culture, the concept of the single story also applies to various identities and disabilities really well.

Stereotypes come from similarities across a group of people—there are almost always shared experiences among cultures and identities and disabilities. Shared experience is part of building that community, and it can be a really validating thing to see other people going through the same things you are. However, human beings are not homogenous; even with shared aspects of identity or being, there is not anything aside from the label/identity/disability itself that will be true of everyone in that group. Still, there is nothing bad about shared experience.

The issue comes into play when those similarities are taken as the definition of that people. When you are only seeing one aspect of a group or a people, you begin to see them as nothing outside of that trait or collection of traits, and that’s the trouble. It dehumanizes people and shoves them into boxes they don’t fit. It erases their experience and claims that there is only a single story of this people, and by perpetuating it, you are erasing the actual people, replacing them with a single caricature. As Adichie says, “The single story creates stereotypes. And the problem with stereotypes is not that they are untrue, but that they are incomplete. They make one story become the only story” (00:12:54 – 00:13:16). Stereotypes begin as something true, but when that is the only thing you know of a group of people, you begin to see real-life people as nothing but the character from the single story you’ve been told of them. You’re not seeing people anymore, you’re seeing your own idea of who they must be according to you and your single story of them. So, while stereotypes might not be untrue, they are often unrecognizable.

Seiji Katayama in Fence: Striking Distance and Fence: Disarmed is unrecognizable. If Seiji in the comics had been depicted from the start as the obviously (and clumsily) autistic-coded character he was in the novels, I would still be upset about it. My skin would have begun to crawl, and I promise you I would have put down the very first volume with a sour taste in my mouth and never picked it up again. But, fine. If that was who Seiji was, depicting him as such in the novels makes sense. That would have been a one-to-one translation. That’s not the case. Seiji’s character was completely changed in translation from the comics to the novels, and the reason behind that incredible shift was this: Sarah Rees Brennan decided Seiji was autistic. That is what I find most hurtful and frustrating and clearly ableist about Seiji in the novels.

Here is a character who is sharp and mean and volatile. A genius in fencing and contentedly inept in people. Someone who clearly doesn’t always understand how other people are feeling but also doesn’t always care to understand. That’s what’s fun and interesting about him, and I believe it will also be satisfying to watch his character grow and start to care about how his words affect other people—though I doubt his sharp edges can ever be sanded away completely, nor would I want them to be. His blunt, harsh interactions with people are part of who he is and that’s one of the things about him that can easily be read as autistic. There are so many aspects of Seiji in the comics that can be read as autistic. Though I doubt it was intentional coding, there are definitely parts of his experiences that resonate with the autistic experience. The most obvious, of course, being his complete obsession with fencing and his disinterest in socializing. There are subtler ways, too, that his autism could be argued to present in the comics: his rigid routines, his specific and precise diet (though part of the fencing regime, it could also be seen as a sensory thing/safe food or a routines thing), his headphones that are used to block out noise (another sensory thing), wearing socks to bed (yet another sensory thing), his break downs triggered by ‘little’ things (that’s such an emotional dysregulation thing, which isn’t a diagnostic requirement of autism, but is a common symptom of autism spectrum disorder), even the way he interacts with both Jesse and Nick can be indicators (the obsession with Jesse to the point of seeing him in other people, and the complete disregard for personal space and boundaries when he's upset at Nick—just getting in his face or dragging him around and not getting why that's inappropriate/what other implications dragging someone into a closet might have).

But here’s the thing. Seiji’s autism in the books wasn’t based on Seiji’s character in the comics. It was based on the single story of autism. Seiji’s fixation with fencing is great to read as a special interest, carrying that over makes sense—special interests are all-consuming…but they’re not the only part of an autistic person’s personality. Since the comic hasn’t had time to actually give the characters too much context outside of fencing, I can let this one slide—though it would have been nice to see his personality expanded beyond fencing when there was actually the time and space to do it. That, however, is the only thing I can let slide. The way Seiji’s social issues were carried over was so crudely and demandingly done that I wince constantly whenever I think of him in the novels. As that’s just about the only other thing taken from the comic, let’s go into more detail on all the ways it was done to infantilize him, and, by extension, autistic people.

I know I’ve talked on this a lot, but Seiji isn’t exactly the sweetest pea in the pod, and I genuinely don’t know how some of the things he says could be read as anything but intentionally barbed and hurtful. Autism is really fun because there’s lots of different ways social interactions and cues can get lost in translation! Seiji’s a bitch, and, yeah, some of the shit he says is him genuinely not understanding why he doesn’t get to say that, and part of it is that he doesn’t care to understand because it doesn’t matter to him. We could have examined that side of his social issues rather than turning him into an infantilized autistic poster child who is clueless beyond any realism and who is too childlike and dumbly sweet to ever say anything mean, much less mean or be accountable for any of the shit he says that hurts people.

Autistic people are absolutely capable of being intentionally hurtful; we have the mental capacity to realize when something we are saying is mean, and we have the responsibility to learn how to interact with other people in a way that doesn’t hurt them, even when being anything less than bluntly truthful doesn’t come naturally. What I’m saying is the spin on Seiji’s social issues seen in the novels is much more about showing him to be autistic than about building him as a character, and it shows. I have said it before and I will say it again: fitting Seiji to autism instead of fitting that disability to who he is as a character is actually just prejudice. The things that make Seiji autistic should just be the things that make Seiji Seiji. It shouldn’t change him from who he is in the comics at all to write him as autistic—to do so is to say that he was not autistic enough, or not autistic in the right way, in the comics. Because the Seiji Katayama in the comics does not conform to the single story of autism, he was made to conform to it in the books, robbing him of authenticity and making him into another ableist caricature of autistic people.

It is unpleasant to see a character robbed of the autonomy to so much as be mean because he is autistic, and in general a really harmful mindset to hold toward neurodivergent people—remember that while our disabilities can explain behavior, they don’t excuse us of all wrongdoings and hurts we cause. The mentality that we should get away with everything just because we’re autistic is dangerous to both parties—it enables abusive behavior among abusive (in this case) autistic people, and it also dehumanizes and infantilizes autistic people by stripping so much as the ability and freedom to be unkind away from us.

But what’s worse by far is the fixation on sexual ignorance presented in the books. We really never dropped the gag of a missed reference to sex in the comics, dragging it out across both novels to such an extent that even the original joke is no longer funny. Because the novels took that joke and made it a core personality trait that was weirdly prominent. To emphasize the lack of understanding about sex and sexual relationships is just as weird as fixating on hyper-sexuality would be. But in conjunction with Seiji’s autism, it’s an even more unsettling fixation. Autistic people—and many other neurodivergent and/or disabled people—are so often seen as unable to consent to sex because we don’t count as fully cognitively aware and mature in the eyes of neurotypical and/or non-disabled people. And focusing so much on an autistic character’s complete inability to comprehend sex on any level is just really gross for the way it infantilizes him and makes Seiji seem even more sexless—which is an especially fun intersection with his identity as an Asian male, but that’s a whole other discussion. All the jokes about Seiji not understanding sex get old fast. At best, they’re tiresome slap-stick that make an autistic Asian-American boy the butt of sex jokes. At worst, they’re perpetuating harmful stereotypes that have a real-world impact on how society view and interact with people who they’ve been conditioned to see as incapable of having, comprehending, or consenting to sexual activity.

Now, it is worth noting that Nick is portrayed with similar ignorance to sex with the same cringey and frustrating imbecility played for laughs, and that their behavior is rooted in a canon throw-away joke. I’ve said before that Sarah Rees Brennan took that joke and ran in the completely wrong direction, but it can still be argued that it is canonical. In that case, then, more critical thought and empathy should have gone into how that joke was fit in with Seiji’s autism. Since both the autistic coding and the child-like understanding of sex (which is to say a complete non-understanding) are so heavy-handed, the pieces fit together in an entirely uncomfortable and harmful way.

Moving on to Seiji’s relationship with his parents. Autistic people do not always get wonderful, loving, and understanding parents or families who love them as if it were second nature, as easy as breathing. I know that. Turbulent relationships with families are a reality that a lot of people face—queer and disabled people especially. But here, again, is that single story. It is a given to non-autistic people that an autistic child will have parents who struggle to love them. It is only natural to see any parent who is (eventually) capable of trying to love their autistic child as a hero, as if loving your own child is special or brave just because they’re different. I dislike the relationship between Seiji and his father being held up as evidence for Seiji’s autism because it’s a point-blank admission that you think autistic children are hard to love and that the very attempt to love them is a profound act of bravery on any neurotypical person’s part. The following passage encapsulates Seiji’s relationship with his father and why it is such an unsettling one to set up between neurotypical parent and autistic child:

“You were such a distant kid,” said his father. “You always seemed so hard to reach.”

Seiji responded, startled, “I didn’t think you were trying.”

His father hesitated, then continued with an odd note in his voice: “We should have tried harder. We thought it would be easier to talk to you when you were older, and—it never was. It got more difficult instead. Love was always easy for me and your mother, and I suppose we believed that it would be easy with our child, too.”

…

Seiji had always known he was difficult to love. His father didn’t need to tell him that. (Brennan 318).

“Loving you wasn’t easy” is not something you should be saying to your kid. Seiji clearly internalizes it and believes he is at fault for being unlovable—for being different—for being, in essence, autistic. And here’s the thing, that is an idea autistic children are taught from society itself, through the media we consume to the reactions of people when they discover our autism or our strangeness, it is a message we already internalize, and it’s not a message I really care to see here in Fence. It’s not okay to not address that in this relationship. It’s not okay for Koichiro to put all the fault on Seiji for being hard to love and for them to both move on as if that’s a perfectly acceptable thing to say. It’s not okay for the only autistic character in the books to have such an emphasis on a relationship that boils down to this: Koichiro is an amazing father and a brave, kind man for being willing to try forging a relationship with his autistic son after 16 years of emotional neglect on account of his son being hard to love. Autistic people deserve better than this single story.

Again, I will admit that Seiji’s relationship with his parents is referenced in canon as being distant. But again, if you are going to code a character as autistic, it’s your responsibility to consider how you frame things. It is the glorification of Koichiro, the narrative patting itself on the back for what a good dad he is to the poor little autistic boy, that is especially grotesque. We focus more on Seiji’s relationship with his father than on any other parent involvement—which, from the comics, doesn’t make much sense. The reason we spend so much time with Koichiro is to emphasize how the default with an autistic child is not to love them. And while this may be something that resonates with many people, it is also upheld as the ultimate truth instead of just one truth among many, and “…that is how to create a single story. Show a people as one thing, as only one thing over and over again, and that is what they become” (Adichie, 00:09:17 - 00:09:29). Show autistic people and non-autistic people alike that autistic people are harder to love, and that is what they become. It’s always the autistic kids who have troubled relationships with parents, who are lucky for their parents just to love them. Either give Seiji good parents from the start or keep them as the neglectful parents they were implied to be, don’t give me half-assed redemptions that perpetuate the idea that autistic people are hard to love and should be grateful when thrown a bone.

Seiji as written in the novels is nothing but another version of the same story. Another Sheldon Cooper and Sherlock Holmes. Genius in one area, the butt of jokes for ignorance in others, robotic and awkward, excused of all inappropriate behavior. He is the same story of autism that we have seen a million times before, and he was completely altered in order to fit it. You have to do a lot of mental gymnastics and recontextualizing to make the novels fit into the comics, and for something that was meant to be built from the comics, it shouldn’t be so hard to see the one in the other. Seiji is an entirely different character in the novels, and if you read the comics again and change his every move and motive to add up to the boy he was in the books, you have to do a lot of leg work and a lot of squinting. To see Seiji as autistic, you shouldn’t have to do any of that. You shouldn’t have to rewrite his story to make him autistic. You should be telling and seeing his own story, and have autism be a part of it. Yes, stereotypes can stem from truth. Yes, there are autistic people much like the boy in Sarah Rees Brennan’s novels. No, they’re not wrong or harmful to the autistic community for fitting comfortably into the narrative the rest of the world expects to see in all of us. But that’s not Seiji. And if that’s the character you want to write or read, I don’t think Seiji Katayama should be the one you go to for it, because he is his own story of autism. Or he could have been.

There are so many ways to read and write Seiji as autistic. There are so many ways to have coded him as autistic without making him more ‘autistic’ than ‘Seiji’—more ‘autistic’ than human. He is nothing but his autism in the books, and it does a disservice to his character and to autistic people—our autism is a part of us, it is not the only thing we are. I do think the coding came from good intentions, but it was very poorly done and revealed a lot of implicit bias. The idea of Seiji being autistic turned into the reality on-page of an autistic caricature with the name Seiji Katayama scrawled across his forehead. If so much effort hadn’t gone into making Seiji so evidently and ‘classically’ autistic, he naturally would have read as more autistic by simple merit of being him. To intentionally code him as autistic, more care should have gone into looking beyond the typical qualities of autism you see everywhere in media (childish, robotic, stupid, incapable of understanding sex, mean but it’s okay because the baby doesn’t know better). Autistic people deserve to be picky about autistic representation. Just because the Fence novels gave us yet another single story of autism doesn’t mean we have to sing its praises because ‘There’s an autistic person in this book! What more could you want?’

I want more than what we got. I want better. I want a Seiji that doesn’t make my skin crawl to read. I want to be able to see the headcanon of autistic Seiji without cringing away. I’ve been in the fandom since 2018, and I never saw any headcanons about Seiji being autistic until this last year. Autistic!Seiji is very much a thing of the novels. And, on the one hand, it’s cool that people are on board with him being autistic…it’s just a little unfortunate, in my opinion, that he’s only been seen that way since being turned into a stereotype. So, if you only started reading Seiji as autistic after reading the novels, ask yourself why. And then ask yourself if the boy in the novels is still Seiji, or if he just matches the story of autism that you recognize.

Works Cited

Adichie, Chimamanda Ngozi. " Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie TEDGlobal 2009 The danger of a single story." ted.com, uploaded by TEDGlobal 2009, July 2009, https://www.ted.com/talks/chimamanda_ngozi_adichie_the_danger_of_a_single_story?language=en

Brennan, Sarah Rees. Fence: Striking Distance. Little, Brown and Company, 2020.

120 notes

·

View notes

Text

I started playing around with a sunset palette and don’t want to stop

77 notes

·

View notes

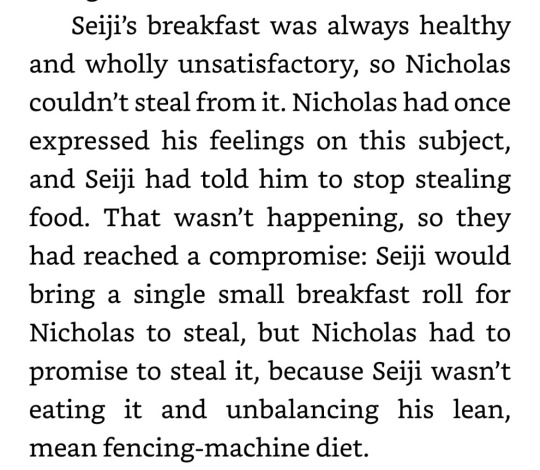

Text

- Fence: Disarmed

Hmm… where have I seen something like this before …

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

It’s like I can’t think of anything except for the boys

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

maybe now is not the best time to have an oh. moment, seiji??

bonus:

387 notes

·

View notes