Text

Black Men in Britain

Why is it I only feel English in the Caribbean, and a West Indian whilst in Britain? Why do those born in the West Indies arrive in Britain and only then discover themselves as West Indians? Why do blacks born in Britain cleave so much to the Caribbean, whilst those born in the Caribbean cleave to the ideals of ‘ Britishness ’ ? Why is it so dif fi - cult to be a black male in Britain? How does this cultural mishmash of identity have an impact on broader sociological issues? And, most importantly, what does it mean to be a black man in Britain?

RESEARCH - S.Selvon/ G.Lamming/ Sir D.Walcott/ P.Gilroy/ S.Hall/ K.Pryce/ M.Banton

Paul Gilroy, Stuart Hall, Ken Pryce and Michael Banton regarding the difficulties of blackness in Britain ... I recalled the fabulous novels I had read by Sam Selvon and George Lamming and the poetry of Sir Derek Walcott, who all reminded me of the heavy burden that manifold identities sometimes carry.

The historical experience of colonisation and subjugation and the contemporary experience of social, economic political marginalisation, led to a feeling of insigni fi cance and to an insularity that becomes unbearable because the goals and standards of success in the white world are de fi ned in ways which makes them impossible to achieve. (Fanon, 1967, cited in Bowling & Phillips, 2002:72)

Such ideas have seeped into relatively recent sociological debate. See, for example, Herrnstein and Murray (1994), who suggest that blacks are innately less intelligent than other racial classi fi cations, and as a result are predisposed to deviancy and ultimately criminality. All too frequently, an analysis of crime within sociological literature manifests a subtext that speaks of blacks as offenders, purely in relation to their engagement with enforcement agencies. This is an area of some concern for me as a lecturer in criminology and criminal justice, where I notice a number of modules with a speci fi c focus on ‘ black criminality ’ built into curriculum designs, a focus that has a negative impact on black students, particularly males.

When I fi rst get off the boat I was thinking that my brother would be there waiting for me dress up in top hat and thing, with a carriage, that will carry me to a big house with shag carpet and expensive ornaments. Nothing like that happen boy. London was colder than I ever dream a place could be. When I speak I see smoke – cold it was cold like that! A fella come meet us in an old truck, and take us to our new home. That night is in the bathroom I sleep – in a rusty bath pan amongst three other fellas. All the other places them in the house occupy. Boy I was shame. I get mammagise [fooled] into coming here and living like that, but what to do? (Cletus)

People are really afraid that this country might be rather swamped by people from a different culture. The British character has done so much for democracy, our land has done so much throughout the world, that if there is any fear that it might be swamped, people are going to react and be rather hostile to those coming in. (Margaret Thatcher, World in Action , Granada TV, 1978)

system. Although academic research and literary commentary conducted on blacks in Britain has a lengthy legacy, the main bodies of work that address everyday sociological issues of black life are limited. Consequently there is a chasm in the authoritative and effective investigation of black masculinities in Britain. This is of concern particularly as many of the texts that observe the everyday lives of black males habitually focus on black youth, and ignore black adult or middle-aged populations in Britain (Alexander, 2001; Gunter, 2010; White, 2017).

Complicit masculinity is commonly typi fi ed by the characterisation of the ‘ new man ’ – a male who openly displays his ‘ feminine side ’ and is said to be liberated from the con fi nes of patriarchy. Subordinate masculinity is frequently used to de fi ne homosexual men, and stresses that although homosexuality today enjoys a greater level of tolerance than ever, it is still at times highly stigmatised. But it is the last category, marginalised masculinity that will be the essential concern of this chapter. Marginalised masculinity, according to Connell (1987, 1995), is shaped by economics, social class and race, factors that, I will go on to argue, have had a profound effect on shaping the life course of black men in Britain.

This can be illustrated by the biological fetishism experienced by British Olympian Linford Christie, who, in the early 1990s, was subjected to unpleasant sexualised and racialised medialed discourses about the dimensions of his ‘ lunch box ’ (penis): Linford Christie is way out in front in every department and we don ’ t just mean the way he stormed to victory in the 100 metres in Barcelona. His skin tight Lycra shorts hide little as he pounds down the track. His Olympic sized talents are a source of delight for women around the world. ( The Sun , 6 August 1992) What makes this piece particularly distasteful is the fact that Christie ’ s achievements in track and fi eld were superlative, as he was (and still is) the only British sprinter to achieve gold medal status in all four major athletic competitions. 4 This rekindles Fanon ’ s keen observation about the fascination of black male genitalia, where the black male is not looked upon as a man but simply as a phallus: One is no longer aware of the Negro but only of his penis, the Negro is eclipsed. He is turned into the penis. He is a penis. (Fanon, 1967:70)

Monrose, Kenny. Black Men in Britain : An Ethnographic Portrait of the Post-Windrush Generation, Taylor & Francis Group, 2019. ProQuest Ebook Central, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/mdx/detail.action?docID=5899693.

Created from mdx on 2022-12-15 13:34:46.

0 notes

Text

Education System

Regarding gender, research reveals that black girls tend to outperform black boys and that a signi fi cant proportion of boys compared with girls complete compulsory school with few or no quali fi cations (Archer and Francis, 2007; Rhamie, 2007).

For black boys, research reveals that they are between four and 15 times more likely to be excluded than white boys, depending on the locality (Sewell, 1997; Department for Education and Employment, 2000a, 2000b) and black girls are four times more likely to be permanently excluded than white girls (Wright et al, 2005).

"Given the key role of education in facilitating social mobility, what does denying access to education through the process of exclusion say about social justice?"

"Parekh (2000) argues that education is a virtue in all democratic societies and serves as a gateway to employment for all citizens. Alongside social justice and social mobility, education is also seen as essential for encouraging greater social cohesion. Further, Parekh (2000) concludes that the British education system, though designed to meet the needs of its citizens, does not appear to equip a large proportion of young black people with the skills needed to achieve their full potential.

Indeed, as already discussed, Gillborn (2008) argues that educational ‘ race ’ inequality in the UK, particularly in relation to schooling, is a form of ‘ locked-in inequality ’ whereby the schooling system is seen to disadvantage young black females and males in two ways: through school exclusion and inequality of attainment. 2 What is therefore a major issue here is the implication of this form of locked-in inequality for social justice. This study represents not only a key issue regarding social identities and social justice in education but it links the discourse on the problematic relationship between ‘ race ’ and education that has framed UK social democratic policy since the 1960s with contemporary concerns with how young black people ’ s schooling experiences shape their transitions on leaving compulsory education. It is argued that a way of understanding the in fl uence of di ff erential experiences of transition for young black people is to examine the role of education. In particular, how school exclusion a ff ects their life chances and the nature of their transition."

"However, as Branglinger (2003) points out, ‘ the classical ideological “ American dream of social mobility ” combined with tales of “ school as meritocracy ” cause a range of students to believe that the playing fi eld is level and those who excel do so by virtue of natural talents while those who fail are lacking ’ (p. 7). As mentioned in the introductory chapter, the educational resources playing fi eld was constructed to create inequality between blacks and whites (e.g Ladson-Billings, 2006) but it would appear to remain unequal to this day (Roza and Hill, 2004; Education Trust, 2006; Ladson-Billings, 2006; Liu, 2006)."

Wright, Cecile, et al. Black Youth Matters : Transitions from School to Success, Taylor & Francis Group, 2009. ProQuest Ebook Central, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/mdx/detail.action?docID=465328.

Created from mdx on 2022-12-11 16:19:45.

0 notes

Text

Quotes that relate to black masculinity

For the past several decades, women have worked hard to redefine ‘femininity’ and ‘womanhood’, while ‘manhood’ has conceptually remained stagnant. According to Athena Mutua:

Essentially, as more African Americans join the ranks of the middle and upper classes, what we know of as Black Masculinity may eventually be called Working Poor Masculinity.

0 notes

Text

Hair Story

Black Hair in Bondage is a chapter that focuses on black hair during the torments of slavery and the lives Africans had to adopt in America. Byrd and Tharps begin the chapter discussing the fact that most Black Africans had been placed in the south of North America on plantation fields where they were forced to work 12–15-hour days seven days a week in the southern heat. Slave owners showed no compassion and would often work their slaves to death. During these times it was hard for the Africans to care for their appearance including their hair (Byrd and Tharps, 2001).

Many White people went so far as to insist that Blacks did not have real hair, preferring to classify it in a derogatory manner as "wool." Descriptions of Black hair in the early 1700s- in runaway slave advertisements, slave auction posters, and even the daily newspapers use this classification, almost as if by likening the hair to an animal's, Whites would be validated in their inhumane treatment of Blacks (Byrd and Tharps, 2001).

These early derogatory representations of Black people in runaway slave advertisements and slave auction posters haven’t disappeared from western media. The negative representations in the past were used to validate slavery. Now in modern times we see negative representations (although more subtle) hindering the progression of black people and their chances of success. Terms such as thug being used to describe black men who haven’t been involved in crime is common in American media. For example, Smiley, C., & Fakunle, D. (2016) state “political adversaries of President Obama such as Michelle Bachmann, Karl Rove, and Rush Limbaugh have referred to him as a “political thug.”

I think it’s important to remember that these derogatory representations based on African hair, skin and features have lingered for centuries. The whites Brainwashed Africans to think of themselves as worthless to make blacks easier to control. Darker skin and kinkier hair meant lower social status with lighter skinned blacks ranking higher. Over time blacks would attempt to straighten their hair to live better lives, all of this created a divide between dark and light skin blacks that still exists today.

The decision for many African Americans to wear their natural hair in afros in the 1960s and 70s was liberating. It's essential that we continue to celebrate black hair and its beauty to remove the negative connotations that kinky hair holds. That is what I aim to do with my etchings which will feature three black women showing off elaborate hair styles. The choice to use black women was because their relationship with natural hair is far more complex than the black male, and they’re still more likely to straighten their hair in the present day.

Reference:

Byrd, A. and Tharps, L. (2001) Hair Story. New York: St. Martin’s Griffin

Smiley, C., & Fakunle, D. (2016). From "brute" to "thug:" the demonization and criminalization of unarmed Black male victims in America. Journal Of Human Behavior In The Social Environment, 26(3-4), 350–366. https://doi.org/10.1080/10911359.2015.1129256

0 notes

Text

Rembrandt

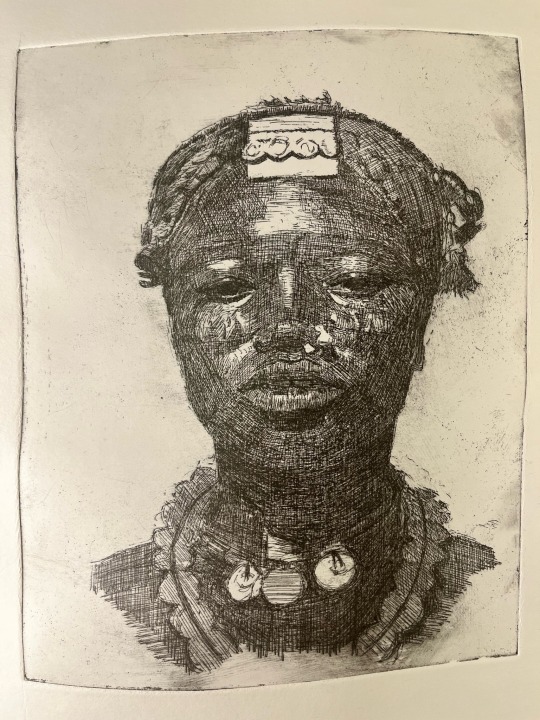

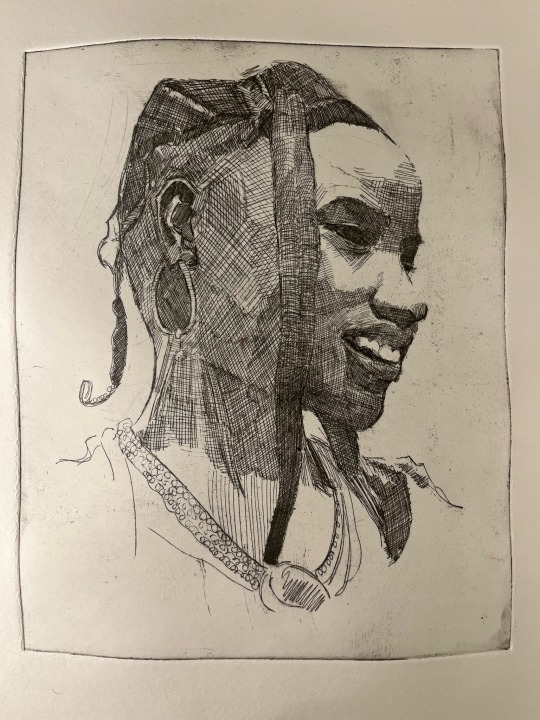

I’m researching Rembrandt as I have decided to create portraits of African people and their elaborate hairstyles to celebrate black hair in a medium that was predominantly used by Europeans... Etching.

An old master print is a work of art produced by a printing process within the Western tradition. The term remains current in the art trade, and there is no easy alternative in English to distinguish the works of "fine art" produced in printmaking… that grew rapidly… from the 15th century onwards…A date of about 1830 is usually taken as marking the end of the period whose prints are covered by this term (Wikipedia, 2022).

Old master prints are simultaneous with Slavery in Africa and it is interesting to see the depictions of Africans in this type of art. The 17th century and the age of Rembrandt was a time when etching became the normal medium for printmaking and “by the middle of the 17th century, slavery had hardened as a racial caste.”

An exhibition called Black in Rembrandts Time “tells the story of the black community in 17th century Dutch society and how the portrayal of black figures in Western art reveals much about attitudes to race”(DutchNews.nl, 2020). The exhibition aimed to destruct the idea that there were no free Blacks in Europe during this period. It’s rare to see masterfully painted portraits of Black people because these types of paintings were usually reserved for people of a higher class. However, the exhibition displayed realistic paintings that contrasted to the “negative, caricatured depictions of black people which came later” (DutchNews.nl, 2020).

The exhibition also displayed Rembrandt, Bust of a Woman, 1630. An etching of an African woman likely to be a neighbour that he asked to sit for him. The woman takes centre stage which is significant because often blacks in Rembrandt and peer’s work were seen as secondary figures. Unfortunately, the positive depiction of Africans in printworks is drowned out by drawings of slaves and the racist stereotypical caricatures that later became so popular in the West.

References:

DutchNews.nl (2020) Black in Rembrandt’s time: a myth-shattering exhibition on identity and truth. Available at: https://www.dutchnews.nl/features/2020/03/black-in-rembrandts-time-a-myth-shattering-exhibition-on-identity-and-truth/ (Accessed: 10/04/2022).

Wikipedia (2022) Old master print. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Old_master_print#17th_century_and_the_age_of_Rembrandt (Accessed: 10/04/2022).

0 notes

Text

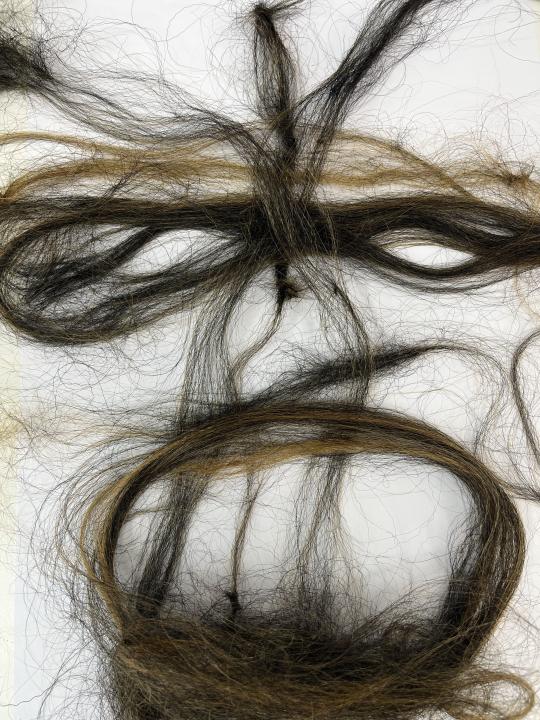

Sonia Boyce

Sonia Boyce is a “British Afro-Caribbean artist, living and working in London… Boyce's research interests explore art as a social practice and the critical and contextual debates that arise from this area of study” (Wiki, 2021). She was a part of the 1980s British Black Arts Movement that was “founded in 1982 inspired by anti-racist discourse and feminist critique, which sought to highlight issues of race and gender and the politics of representation” (TATE). Her work is formed by ideas concerning identity and culture, with her early works expressing her personal thoughts, feelings and questions.

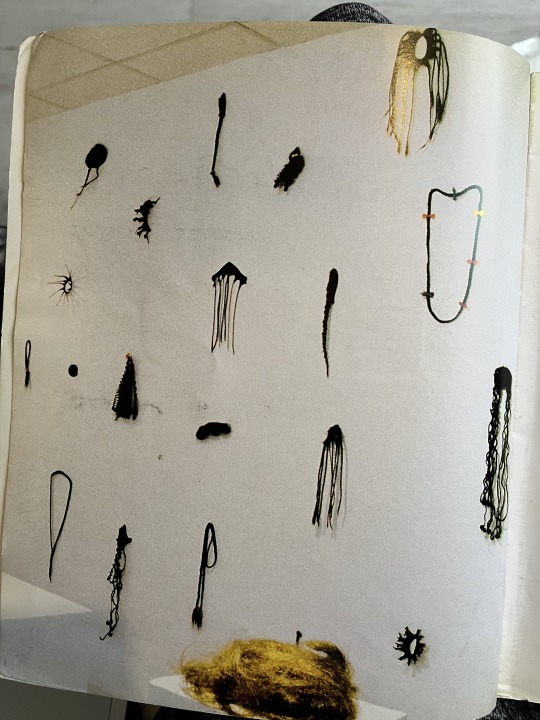

Sonia Boyce is an amazing inspiration for young (especially Black British) Artists. Her ideas and concepts give me different perspectives and provide me with new opinions regarding topics of identity. My current graphic design project is about the history of African hair, I was sure Sonia Boyce would have work that focuses on hair that would guide me for my own project. I came across her installation “Do You Want to Touch?” in Tawadros’ (1997) book that showcased her doodles with hair bought from Afro-Caribbean hair shops. Explaining the title, Boyce (2018) states that “Usually it can be a stranger coming up to someone wanting to touch their hair. It harks back to a very long memory of the African body being public property.” This is similar to Bell Hooks’ theory of eating the other which I touched on in a previous post where Western culture look at the African body as if it is something for their own consumption, they believe it is public property. This Western mindset is possibly what made colonising Africa easier to perform and justify.

The hair being detached from the head gives these sculptures an unpleasant visual contrasting to how people perceive a nice hair-do in the everyday. To respond to Do You Want to Touch? I will collect hair from shops like Pak’s and experiment with the hair using soft ground etching plates and rolling it through the press hopefully creating some sort of texture. I’ll also attempt to ‘doodle’ with the hair myself.

References:

Wikipedia (2022) Sonia Boyce. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sonia_Boyce (Accessed: 19 April 2022)

Boyce, S. (2018) 'Gathering a History of Black Women'. Interview with Sonia Boyce. Interviewed by Tate for Tate, 27 July. Available at: https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artists/sonia-boyce-obe-794/gathering-history-black-women (Accessed: 05 April 2022).

Tawadros, G. (1997), Sonia Boyce: speaking in tongues / Gilane Tawadros. London: Kala Press

Tate, BRITISH BLACK ARTS MOVEMENT. Available at:

https://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/b/british-black-arts-movement (Accessed: 20 April 2022)

0 notes

Text

Go West Young Man by Keith Piper

Keith Piper is a British artist who was a founder member of the ground-breaking BLK Art Group, an association of black British art students (Wikipedia, 2022). Looking at a few of his artworks I notice that he enjoys combining visuals and text/narrative. ‘Go West Young Man’ is a piece that demonstrates this and (Piper, no date) explains what brought the two together:

The concept for the work ‘Go West Young Man’ was initially triggered by an act of juxtaposing the notoriously graphic engraved plan of the English slave ship, ‘The Brookes’, first published in 1788 by the Plymouth Chapter of the ‘Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade’, with Horace Greeley’s evocative call of 1865 for white male settlement of the American Prairie.

Piper was fascinated by the tension between Horace Greeley’s optimistic call to go west with the harsh realities of the forced hauling and abduction of African peoples into the western hemisphere through the tragic ‘middle passage (Piper). The found image and text progressed into multiple versions with the earliest piece “produced in 1979 and displayed in the exhibition ‘Black Art an’ Done’ in 1981” (Piper). It then “developed into a computer animation produced using a ‘Commodore Amiga’ as part of the ‘Animate’ series funded by the Arts Council of England and Channel 4 in 1996” (Piper). In Piper’s animated video he demonstrates how historic racism of black people is evident in modern times, with a sequence of images beginning with the ‘engraved plan of the English slave ship’ to horrible images of slavery rolling into negative representations of the black male in modern media.

Graham Williamson’s established the visual link between the rave scene and Piper’s animation style. Williamson (2019) acknowledged that “rave was prone to appropriating concepts and styles from indigenous cultures: one of the longest-lasting rave festivals was called "Tribal Gathering." With this connection it is possible that Piper wanted people to understand that indulging in black culture doesn’t mean that you care about the long-lasting misery that black people have endured. Williamson (2019) concluded his review stating that a “drum 'n' bass album in a Mondeo's CD changer is not, it turns out, a method of reparation”.

Analysing ‘Go West Young Man’ made me realise how an initial concept can take time to be developed into a thorough visual display. Piper started the artistic journey with found image and text, and over the course of 17 years it developed into a 4-minute film that showcases the deadly joke that has stressed black people for 400 years. Keith Piper’s work relates to my topic of black representation because the work evolves around black identity and how black people are still treated and represented as other today.

References:

Wikipedia (2022) Keith Piper (artist). Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Keith_Piper_(artist) Accessed: (1 May 2022)

Keith Piper (no date) keith piper 'Go West Young Man'. Available at: https://keithpiper.info/gowestintro.html(Accessed: 1 May 2022)

Williamson, G. (2019) Go West Young Man 1996. Available at: https://letterboxd.com/film/go-west-young-man-1996/reviews/by/activity/ (Accessed: 1 May 2022)

1 note

·

View note

Text

Blaxploitation

My writing on black representation in comic books led me towards the genre of blaxploitation film that was heavily criticised for its negative representation of black people. It was a short-lived film craze that David Walker (2009, p. viii) suggests “is neither positive nor negative; it simply is what it is.” However, I aim to research the positive and negative impacts that this sub-genre of film had on the black community.

A major positive was that there was a huge increase of black representation on the big screen comparing to the decades before where the rare appearance of a black person was represented as mammies, uncle toms, sambos, coons etc. Sometimes the representation of a black person was played by a white person in blackface. These negative representations were replaced by “new archetypes, including drug dealers, pimps, and hardened criminals.” Walker (2009, p. x)

Another plus is that it launched the careers of many black actors and film directors who could then add new, positive perspectives in black films. Walker (2009, p. x) states:

Singleton’s Boyz N the Hood (1991) borrowed heavily from Cooley High. Keenan Ivory Wayans launched his directorial career with the blaxploitation spoof I’m Gonna Git You Sucka (1988). The films Training Day (2001) and American Gangster (2006), both starring Denzel Washington, are nothing if not expensive blaxploitation films. And the career of Will Smith, who has emerged as a major box office star, would not be what it is today if films like Superfly and The Mack (1973) had not changed everything.

The main negative and the core reason for criticism was stereotypical depictions of the main protagonists being pimps or convicts, misleading audiences to believe all black men were like this. This brought major backlash as critics wanted to see these characters become role models for communities. Personally, I believe the positives of the blaxploitation genre out-weigh the problematic stereotypes and it was a steppingstone for black creatives to burst onto the film industry scene. Although many claim that blaxploitation films only lasted 5 years, they have impacted popular culture, for example hip-hop, “A less obvious mutation ... which drew heavily from the mythology created by the films” Walker (2009, p. x)

Reference:

Walker, D., Rausch, A.J. and Watson, C. (2009) Reflections on Blaxploitation Actors and Directors Speak. Lanham: Scarecrow Press.

0 notes

Text

Pen and ink drawings of Ghanian women and their hairstyles

I noticed that most the women I drew were wearing their hair in a headwrap. I researched why and found out the history and symbolism behind it. “Originating from sub-Saharan Africa, these headwraps were initially worn by women during the early 1700s and often indicated their age, marital status and prosperity” (Sikaa, 2018).

The headwrap had opposite meanings in the United States and across Europe, where it symbolised slavery and servants, It later became associated with black women being depicted as ‘mammies’ (Sikaa, 2018). The start of the 20th century saw the introduction of the first chemical relaxers designed to straighten and grow natural black hair. While the method was highly criticised for encouraging European beauty standards, it became popular among African-American women and led to the headwrap taking on a much more functional use (Sikaa, 2018).

The durag was soon invented off the back of the headwraps popularity, men could now protect their new fashionable hairstyles and it has become a popular fashion accessory in the 21st century. The headwrap is a “proud symbol of identity and defiance” and it represents black intuitive expression amid oppression and slavery. In Africa today headwraps are used for functionality as well as fashion. It’s a stylish way to protect hair from the African heat.

References:

Sikaa, (2018) The Fascinating Story of The African Head Wrap. Available at: https://www.sikaa.com/blogs/blog/the-fascinating-history-of-the-african-head-wrap (Accessed: 15.03.2022).

1 note

·

View note

Text

Super Black & Black women in sequence

Super Black and Black Women in Sequence are two readings that focus on black comic book characters and how their identities responded to the social dynamics of the times they were published. Both readings analysed Black Marvel and DC superheroes as Nama (2011, P.4) states that they “speak to a broader audience and reach than alternative outlets”. The broader reach meant that the influence of these Black characters was extremely important in aiding shifts in equal rights and racial issues in American society. In this writing about Super Black and Black Women in Sequence I aim to; look at the representation of characters and relate them to their relevance to the social and political notions of their period. I’ll also analyse how Black Marvel and DC super-heroes reflected American culture and I will also compare the views that the two authors shared and examine whether they drew similar conclusions.

As younger children I believe we tended to take what we consumed from media at face value maybe not having the skills to decipher hidden meanings and symbols. Often as we get older, we re-read or watch some of our old-favourites and realise they were not as innocent as we once believed. This was the case for me and Tarzan when I researched Sonia Boyce and found her artwork From Tarzan to Rambo which articulated how racist stereotypes were prominent in Hollywood films. Nama (2011, P.10) touches on Tarzan when he states it, “reinforced real racial hierarchies by repetitively depicting whites as victors over black people and chronically portraying blacks as representatives of the forces of evil.” These negative representations of black people can subconsciously effect audiences to believe these stereotypes and impact the minds of young children. Young white children that watched Tarzan would feel superior to their black class mates leaving the black children to feel inferior. This has been backed up by “the doll tests” that were initially carried out in the 1940s the same period that Tarzan films were showing. By highlighting Tarzan, we can see how characters in media can have negative influences and why it was important that more positive black representations needed to appear.

Nama (2011, P.11) claims that in the late 1960s and early 70s “American pop culture began to shed its escapist impulses and boldly engage the racial tensions that America was experiencing” New superheroes such as DC Comics’ Green Arrow and Green Lantern took on new roles and were concerned with race related issues. Although these characters were white its still possible to identify the shift in attitude which reflected American culture of the time and they represented white American’s that had to question themselves in order to resolve racial injustice. X-Men were created by Stan Lee and Jack Kirby in 1963, Whaley (2016, P.106) writes that “Scholars… have interpreted the X-Men series as an allegory of the plight of Black Americans, Jews, sexual minorities, and other historically marginalized groups in the United States and abroad.” Professor X and Magneto often being dubbed as mouthpieces of Martin Luther King and Malcolm X we definitely start to see how these comics mirrored society. In 1976, writer Len Wein introduced the Kenyan-born mutant Storm, a positive black super-heroine who represented feminism “in her struggle as an African woman, as a team member, and as an eventual leader of the X-Men.” Whaley (2016, P.108). These characters questioned the problematic social constructs of America signifying that the late 1960s and early 70s was a time of positive change.

As well as Storm, Whaley drew attention to Nubia (introduced in 1973) and Vixen (introduced in 1981). Although these super-heroines were positive black representatives for young black comic book lovers, there were some fundamental issues relating to their origin stories. Whaley (2016, P.97) poses that:

the ethnic and geographic origins of the characters act as launching pads for a continual process of ethnic extraction from Africa to uphold Occidental or Western conceptions of Africa allowing readers the opportunity to gaze and graze upon Africa. While clearly situated to “eat the other”—to borrow metaphoric phrasing from bell hooks— African female comic book and graphic novel characters represent the contradictions inherent in many forms of popular culture. At different narrative and historical moments, Nubia, Storm, and Vixen work as ideological tools of American nationalism and colonialism. Yet, they paradoxically function as initiators of anti-colonialist political thought and action.

I believe Whaley is indicating that because these females are African it exaggerates the urge to fetishize these women by the Western audience. She used Bell Hooks’ theory of “eating the other” to back this up, a complex theory that questions if westerners commodify non-westerners for personal benefit. A Black-American female character would be far better suited to fight for racial equality in America than a character with full African descent. For example, Falcon the first African-American superhero to appear in comics was introduced in 1969 by Stan-Lee and artist Gene Colan. Nama (2011, P.73) wrote that “Falcon’s flight symbolized black social and economic upward mobility that was right in line with real-world changes.” The fact that he was African-American allowed him to display a complex narrative and was able to represent a successful black man that “climbed on up” in America. A character born and raised in Africa is unable to showcase the same message which is why Whaley (2016, P.119) claims that the use of “African characters create a safe distance of representational responsibility…to make claims to ethnic inclusion without the burden of US guilt.

Super Black and Black Women in Sequence analysed the key traits of the characters they focused on allowing readers to better understand the logic, symbolism and marketing behind their makings. I particularly enjoyed the in-depth review of Falcon in Super Black and when paired with the analysis of the three African super-heroines in Black Women in Sequence I noticed how Nama and Whaley actually make the same conclusions through different characters. Falcon being a good example of a complex origin story and his partnership with Captain America was a “politically provocative relationship” Nama (2011, P.69). Whereas the origins of Nubia, Storm, and Vixen make them “comic book blood diamonds” marketed in a way that offer a “newer, fresher, exotic ground” for Western commodification, but at the same time fighting against colonialist philosophy Whaley (2016, pp.97-119).

I think the main difference between the two readings was that Whaley looked closely at the representation of blackwomen. Its possible that she had read Super Black and noticed that more needed to be said on the representation of black females in comics and other visual forms. If the comics truly reflected the social issues of the time, we could agree that Black-American women were severely under represented and it is possible that the writers of these comics believed that having African female characters was good enough representation for black girls living in America.

I’m not a comic book reader so I never understood the important link between super-heroes and society. The first time I consciously noticed it was when Black Panther was due to release in 2018 and black communities around the world were excited to see a black superhero star in a massive Hollywood Blockbuster. Reading Super Black and Black Women in Sequence allowed me to recognise that positive diverse representation in popular culture is vital for empowering and can help to rid superiority complexes. This leads me onto a new topic of research regarding representation in the Hollywood film industry, where I will be focusing on blaxploitation.

References:

Whaley, D.E. (2016) Black women in sequence : re-inking comics, graphic novels, and anime. Seattle, [Washington] ;: University of Washington Press. ProQuest Ebook Central, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/mdx/detail.action?docID=4305962.

Created from mdx on 2022-04-15 11:02:54.

Nama, A. (2011) Super Black: American Pop Culture and Black Superheroes, Super Black. Austin: University of Texas Press. doi:10.7560/726543. ProQuest Ebook Central, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/mdx/detail.action?docID=3443565. Created from mdx on 2022-04-14 13:27:36.

0 notes