Photo

The children’s television show Tsum Tsum is a series of shorts that features characters from every corner of the Disney franchise. These shorts can be interpreted as advertisements disguised as entertainment. The narrative elements of each short (although insubstantial), convince the viewer, most likely. a child, that they are watching a story play out that includes all their favorite characters, except now the characters are all bean shaped, tiny, and squeak instead of speak. However, the shorts are likely more effective at selling the accompanying plushies than engaging children audiences in meaningful, creative narratives.

0 notes

Photo

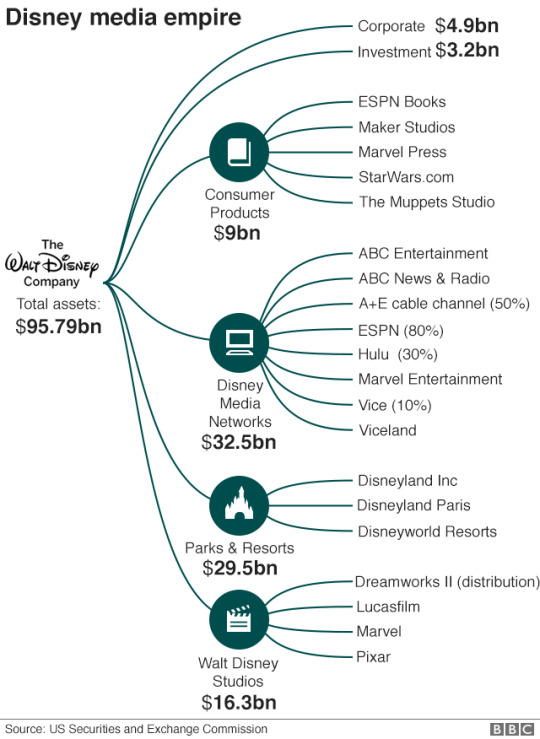

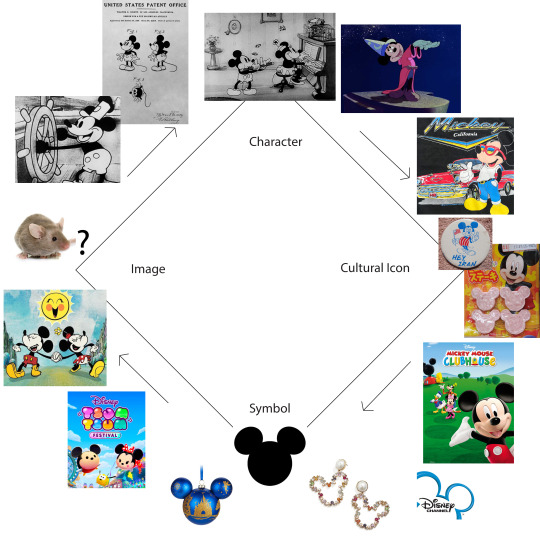

Mickey Mouse as a symbol continued: The distillation of Mickey Mouse down to the silhouette of his head marks the final transformation in this evolution of an anthropomorphic animal character. This basic shape, one large circle to represent the head and two adjoining smaller circle to represent the ears, has come to represent so much more than a simple cartoon mouse. This symbol represents a multi-billion dollar media conglomerate that owns and operates (or has a substantial amount of stock in) the following notable networks and studios: Pixar, Lucasfilm, Marvel, ABC, ESPN, and Hulu (BBC). In fact, Disney is one of the six mega media conglomerates in the U.S.

0 notes

Photo

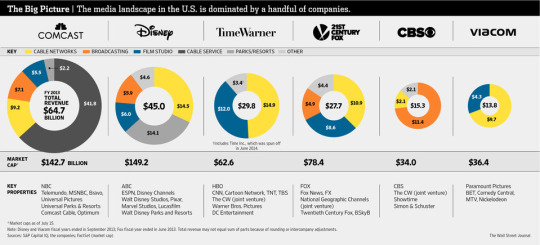

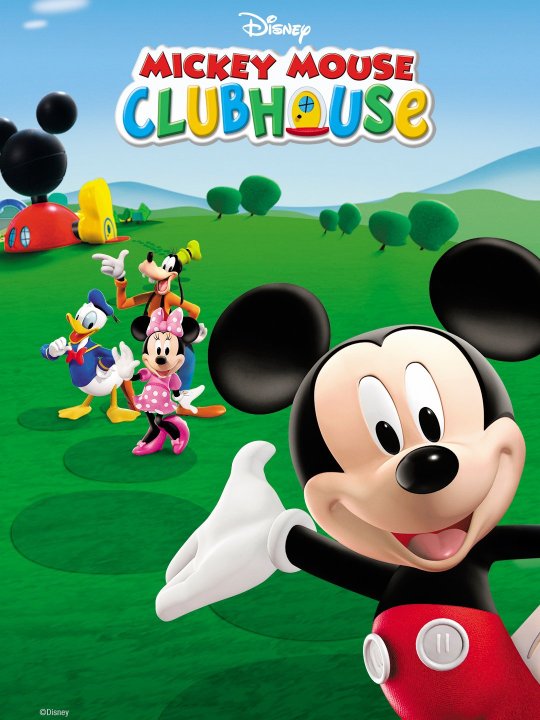

In order to map out the evolution of the Mickey Mouse character, I have created this graphic in which other anthropomorphic characters can also be contextualized and situated. Each stage within the cycle is defined below.

Image: The image stage of an anthropomorphic character’s evolution is the source material for the initial design. The image stage is not one image but a vast collection of images that, together, communicate the intended message/emotion/aesthetic the designer has in mind. Separate, these images lack context, personality, a personal name, a voice, and a manufactured individuality. The image or idea of a mouse (as the supposed source material for Mickey Mouse) does not signify any specific situation (except, perhaps the natural habitat of mice), it does not signify personality, dislikes or likes, it does not have a personal name, it cannot speak as a human can. The image of the mouse, and most other animals, is vulnerable to the industries of advertising and entertainment in that it functions as a blank slate (at least in the eyes of humans during the anthropocene) that character designers can impress an almost endless variety of personalities and situations onto in an attempt to create a palatable individual for mass consumption. The reason animals are so vulnerable to these industries is because humans too often deny animals individuality and autonomy; they become the ideal vessel for new, compelling, profitable characters.

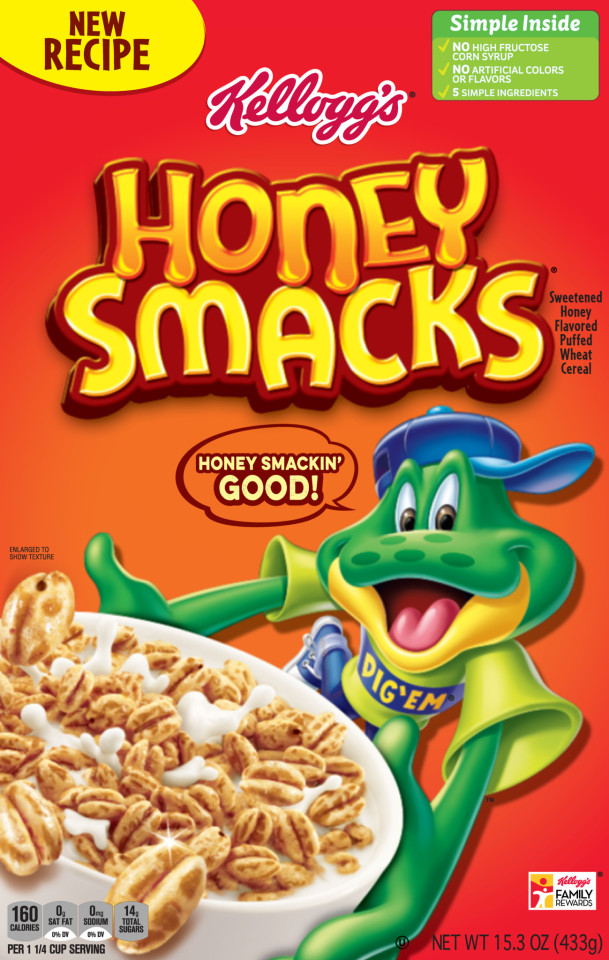

Character: As consumers, we are much more familiar with the character stage of this evolution. This stage entails what you might expect to come after the stage described above; the character has a specific context, individuality, some level of autonomy, predictable behavior, a name, and likely, some way to communicate. A character, however, is not culturally ubiquitous enough to be translated into any and all alternate contexts that diverge from its own original environment. Let’s compare the Cookie Crisp mascot “Chip the Wolf” with Honey Nut Cheerios’ mascot “Buzz the Bee”.

Cultural Icon: A cultural icon, in the context of anthropomorphic animal characters, is a character that has gained a sufficient amount of cultural ubiquity to be copied and pasted onto almost any product (related or not to the original product) and increase the popularity and sales of that product, all owed to the recognizability and/or popularity of that character. “Buzz the Bee” just makes it into this category, evidenced by the unrelated products its images appear on. This evolution is due, in part, to the enduring and effective ad campaigns of Honey Nut Cheerios over the years. On the other hand “Chip the Wolf” does not evolve beyond the “character” stage. “Chip’s” lack of recognizability may have to with The Confusing Cookie Crisp Mascot History in which the mascot changes from a wizard named “Cookie Jarvis”, to “Cookie Crook” and “Cookie Cop”, to “Chip the Dog”, and finally to “Chip the Wolf” in 2005 (Cookie Crisp Commericals - 1977 to 2001). These mascot changes occurred over the course of 28 years, from 1977 to 2005. Whereas “Buzz” first appeared in 1979 and has remained the same anthropomorphic bee character ever since, although he was not given the name “Buzz” until 2000. “Mickey Mouse” has been around long enough and gained an arguably unprecedented amount of cultural ubiquity to be transformed from just an anthropomorphic animal character into a full-fledged cultural icon. This transformation is made clear through all the previous examples of unrelated products that broadcast his image, as well as the appropriations of his image for various propaganda campaigns. But Mickey Mouse does not quit there.

Symbol: This stage of the evolution of anthropomorphic animal characters is indicated by 1. the ability of the character to retain its recognizability when reduced down to its most essential parts (the Mickey Mouse head and ears, for example) and 2. for that reductive image to symbolize more than just the character, but rather, represent entire corporations, countries, political movements, or countercultures. More on this kind of super power in later posts.

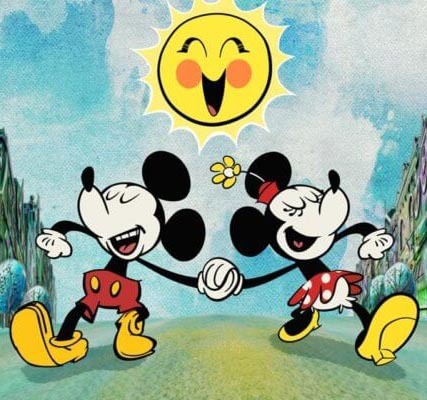

Back into image: This part of the cycle, the space between symbol and the initial image, is a little more tentative than the rest. I would argue that more contemporary shows that feature Mickey Mouse such as Disney's Tsum Tsum and Mickey Mouse indicate a shift toward the original image of Mickey Mouse. The first example, Tsum Tsum, is a collection of comical shorts that usually “star” Mickey Mouse, but also feature every other character in the Disney franchise, from “Dumbo” to “Chewbacca”, from “Mike Wazowski” to “Spider-man”. These shorts reduce all the characters that Disney owns down to their essential parts and tell cute, mostly nonsense stories in which there is no dialogue, only squeaking. More on this insanity later. The second example, simply titled Mickey Mouse, ditches the CGI animation of Mickey Mouse Clubhouse and opts for the more nostalgic two dimensional animation characteristic of the original shorts of the 30s, like The Picnic. This particular Mickey Mouse reboot also represents the characters closer to their original proportions and simplifies the details of their facial features and hands. Another notable reversion is the return of Minnie Mouse’s flower hat rather than her classic pink or red and white polka dot bow. These shows do not return to the original image of “mouse”, but rather, function as a composite for the entire evolution of the character as they return to original design constructions or become extremely over-simplified to enhance their cuteness.

Notes on diverging patterns of the cycle: This cycle does not explicitly play out sequentially; there are likely many examples of character evolutions that diverge from this cycle. They may be adapted into symbols before they can transition into cultural icons. Or they may start as symbols and work their way around. This “cycle” theory is merely a student’s observation of specific patterns in the transformations of popularized anthropomorphic animal characters.

0 notes

Photo

4 continued. An example of anthropomorphic animal characters being deployed as extremely effective advertisements is the onslaught of “cereal mascots” popularized in the 20th century. These characters are arguably less iconic than Mickey Mouse but still deeply recognizable. The commercials featuring these characters make up an essential element of the cereal ad campaigns; without them, these characters lack personality and do not entice the consumer to the extend that a moving, speaking character does. The narrative element of each commercial (the Trix rabbit always just missing out on the Trix cereal, for example) further cements the character (whether it’s a colorful toucan, a bright yellow honeybee in an orange t-shirt, or a large tiger in a red bandana) in the minds of the viewers. The animation of these characters is the fundamental catalyst that transforms them from character into cultural icon.

Videos:

Cocoa Puffs Commercials Compilation Cuckoo Bird

2002 - 2013 Nestle Cookie Crispies Cereal Chips Collection of Adverts

Trix All Commercials 1990s-2000s

Frosted Flakes- Tony the Tiger

Honey Smacks Cereal Commercial 1989

Froot Loops Commercials Compilation Cereal Ads

Cheerios Commercials Compilation Honey Nut Cereal Ads

1 note

·

View note

Photo

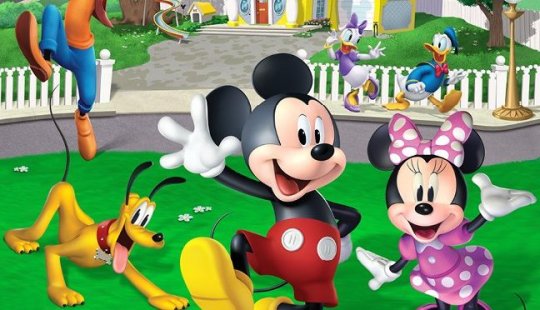

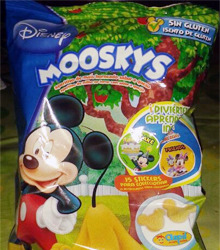

4. In 2006, Mickey Mouse and the gang were adapted (yet again) for a children’s show on Disney Channel, “Mickey Mouse Clubhouse”. This evolution of the Mickey Mouse character continued to accumulate recognition and introduced the next generation (my generation) to the Mickey Mouse franchise. This particular show is made for young children and functions similarly to “Dora the Explorer” in that the characters “talk” to the children watching, ask them questions and wait for them to “respond”. This element of children’s television creates the illusion that the viewer can interact with the characters on screen and effectively manufactures a more tangible relationship between the child and the characters. So, when children see Mickey or Minnie on a can of soup or a bag of chips, those items become more desirable and increase the likelihood of parents buying that product for their children.

Humanoid characters can achieve this too. About one year ago, I saw “Anna” and “Elsa” Campbell’s soup being sold at my local grocery store. I was confused... Would the noodles be “princess-shaped”? The soup cans did not disclose that information. Regardless of noodle shape, humanoid characters seem to be less effective in advertisements than their anthropomorphic counterparts. A possible cause of this perceived insufficiency may have to do with representation; how many children, out of all the children who will see the ad or the product, relate to a highly specific humanoid character like “Anna” or “Elsa”?

Humanoid characters as vehicles for both entertainment and subsequent advertisement pose a few problems. In many cases, these characters are made to represent a specific race or ethnicity, whereas a character that is racially ambiguous might be deemed “too confusing” to the prospective audience or, more likely, to the character designers themselves. Anthropomorphic characters sidestep this “problem” of representing people of different race and ethnicities. Although anthropomorphic characters offer this sidestep, there are many characters that are clearly made to represent a specific race. Mickey Mouse is one of those characters. Mickey is clearly animated with white, human-like skin, along with Minnie and Goofy. Racializing anthropomorphic characters is not anomalous. More on this in later posts.

Another problem is the representation of gender, which can both enhance the effectiveness of the ad and tank it. Because of the way children are socialized into the gender binary in America, many products (soup cans and animated feature films alike) target either boys or girls. The way character designers signify if their product is for boys or girls is through moderate to extreme feminization or masculinization. Anthropomorphic characters have the flexibility to be designed as either, or remain somewhat androgynous. A few signifiers of feminization in anthropomorphic animal characters are: pronounced eyelashes, accessories like bows and flowers, a pink and purple color palette (regardless of the actual color of the animal), and sometimes feminine clothing or anatomical additions like breasts. Hyper-masculinized characters can often be spotted armed with some kind of weapon, wearing armor or “boy” clothes, and represented with a combination of a green, blue, black, and red color palette. To be clear, these are large generalizations of patterns in the children’s entertainment and advertisement industry, however, their pervasiveness is worth noting here. Targeting products towards different demographics is a tried and true advertisement strategy, but what happens when the products aren't feminized or masculinized?

A children's show like Peppa Pig does not feminize or masculinize its anthropomorphic characters to the extent of either of the examples above. How does keeping anthropomorphic characters androgynous effect the ratings of the show and the sale of accompanying toys and other products? I’ve found that, when shows are designed to target an older audience of children, the characters within those shows gain more and more feminizing or masculinizing characteristics, while entertainment for younger children tends to avoid these hyper-fem/masc designs.

In brief, the design and interpretation of anthropomorphic animal characters is much more flexible than that of humanoid characters. Anthropomorphism allows designers to sidestep race and gender identification, or take those identifiers to their extreme, often resulting in offensive caricatures. Either way, this specific flexibility proves effective and profitable in the entertainment and advertising industries.

0 notes

Photo

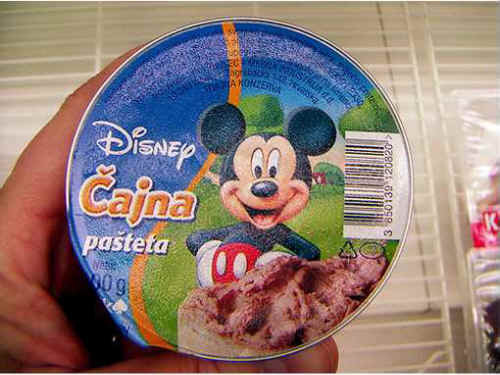

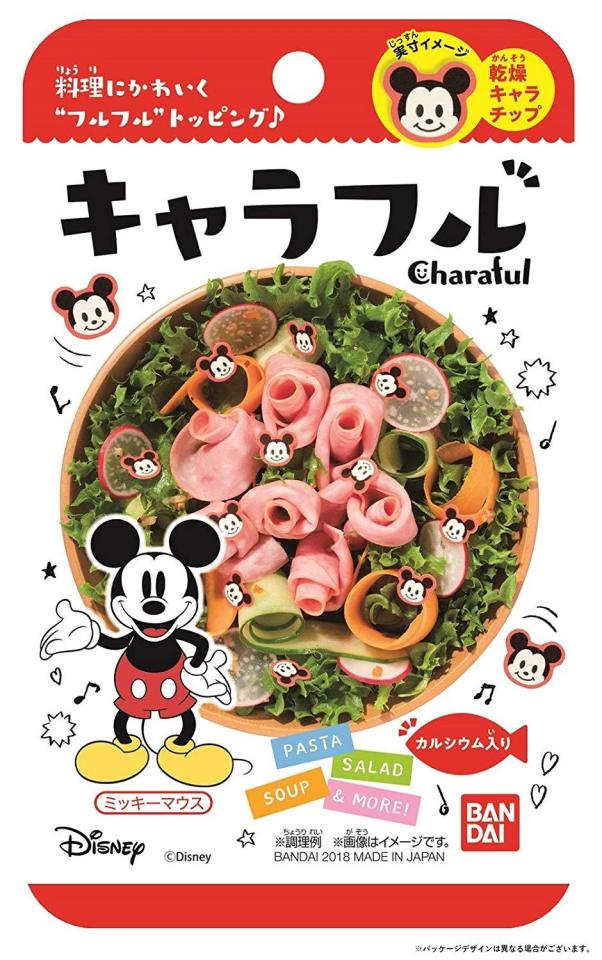

3 Continued. Along with being used as political propaganda, Mickey Mouse’s image has been copied and pasted onto food products all over the world. A little bit less concerning, perhaps, but still somewhat eery. Most often the food item is manufactured to resemble Mickey Mouse’s head shape, but sometimes the connection between the product and the Mickey image is more subtle or completely removed.

Mickey Mouse, and other extremely recognizable anthropomorphic characters like him, further blur the line between contemporary entertainment and advertisement. At a certain point, it becomes difficult to distinguish one from the other. Do television shows and movies featuring Mickey Mouse ever function as one extended ad? Do narrative commercials ever function as entertainment, or at least attempt to feign the qualities of entertainment? How does placing an image of Mickey Mouse (or any other anthropomorphic equivalents) onto a package of food increase the “entertainment” factor in the consumer’s experience?

More on how anthropomorphic characters are the ideal form or candidate for blurring the line between entertainment and advertisement in the posts to come.

0 notes

Photo

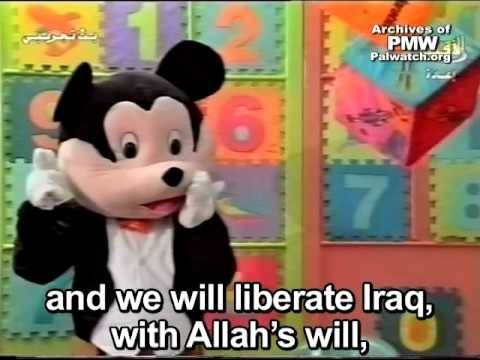

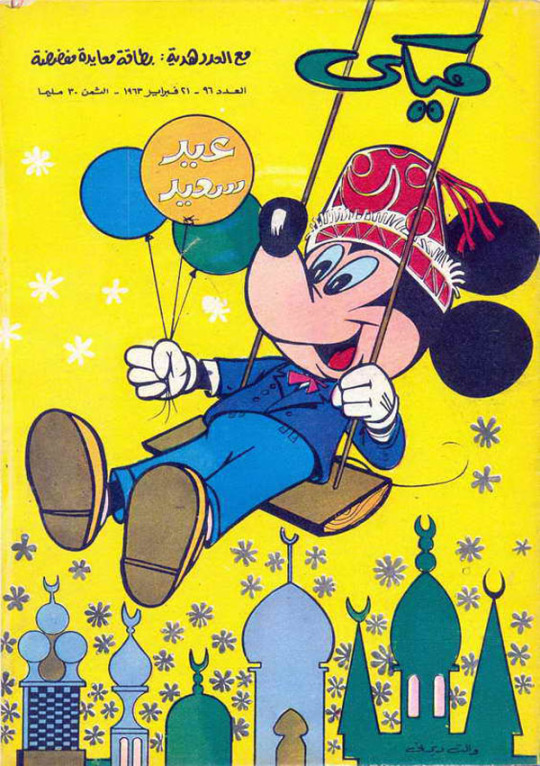

3 Continued. In addition to being stamped with contexts outside of the character’s original written narrative, Mickey Mouse has been co-opted for political propaganda.

Content Warning: Anti-semitism, simulated/suggested violence, and islamophobia

The top three images are from a children's television show, Tomorrow’s Pioneers, which aired from April, 2007, to October, 2009 on Al-Aqsa TV in Palestine. The show features an 11 year old girl, Saraa, and her co-host “Farfour”, in which they perform skits that represent and criticize the Israeli occupation of Palestine. “Farfour” the mouse speaks in a high-pitched tone, and is clearly a Mickey clone. On the show, Farfour often expresses anti-Semitic and anti-western sentiments and has been criticized as “a recruitment tool for Hamas”(Observer) by political analyst Hani Habib. Eventually, Mickey Mouse/ Farfour is beaten to death by an Israeli interrogator and is revered as a martyr. You can read more about Tomorrow’s Pioneers here and here.

The “Hey Iran” Mickey Mouse images were most likely manufactured and dispersed in the early 80′s following the Iranian Revolution (1978-1979) which saw the Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi overthrown and the Pahlavi dynasty terminated, as well as the Iranian Hostage Crisis and the 1979 Oil Crisis.

The image of Mickey Mouse as a symbol of Western/American culture (and subsequently settler colonialism and imperialism for many) has been co-opted to this day to spread political messages in many countries, with many differing values and goals in mind.

sources:

Zoepf, Katherine. “In Palestinian Territories, Tragedy Made for Children's TV.” Observer, Observer, 13 July 2007, observer.com/2007/07/in-palestinian-territories-tragedy-made-for-childrens-tv/.

Laramie, Charles. “U.S. and Israel Are Wagging the Dog.” Rutland Herald, 25 May 2019, www.rutlandherald.com/opinion/perspective/u-s-and-israel-are-wagging-the-dog/article_0ae2f727-fd73-5aea-a4f2-360e86c7c07f.html.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

3. After Fantasia, Mickey Mouse began the transformation from mere animated character into cultural icon. Let’s take a look at the first image, a Mickey Mouse T-shirt listed as “vintage 80s”. The blue jeans, a white t-shirt with the sleeves rolled up, red, quasi-aviator sunglasses, and a red, chrome-plated sports-car with a license plate that reads “2-cool”. Put a red bomber jacket on him, pop the collar and Mickey Mouse is now James Dean in Rebel Without a Cause. This image drips with Americana. So what’s the point? Mickey Mouse was developed by Americans so he is an American character. But that’s not all there is to it. At this point in time, Walt Disney’s character “Mickey Mouse” had evolved to be an extremely recognizable vessel of sorts to be impressed with different circumstances or cultural contexts, what I will refer to as “stamping”.

As Mickey Mouse accumulated more recognizability across the globe, he was able to be “stamped” with more and more cultural contexts, usually (but not always) resulting in derogatory caricatures. More on this in upcoming posts.

0 notes

Photo

2. Fantasia took Mickey’s character in a whole different direction. The 1940 animated musical is regarded as a turning point in the history of animation. It is one of the first extremely successful, full length, animated films that committed to incorporating sound and music as an integral element. Fantasia features Bach's "Toccata and Fugue in D Minor," Tchaikovsky's "The Nutcracker Suite," Dukas's "The Sorcerer's Apprentice," Stravinsky's "The Rite of Spring," Beethoven's "Sixth (Pastoral) Symphony," Ponchielli's "Dance of the Hours," Mussorgsky's "Night On Bald Mountain" and Schubert's "Ave Maria". A cinematic triumph of its time, Fantasia cemented Disney’s “Mickey Mouse” character into the American psyche. In fact, the first search results for “fantasia” describe the film as “a vehicle to enhance Mickey Mouse's career”. This film marks the beginning of a transformative cycle from image, to character, to cultural icon, to symbol (and sometimes, back into image), that I will explore in the posts to come.

On another note, although Fantasia veers away from the slapstick violence that permeates the shorts of the 30s, the film retains the practice of extreme feminization and sexualization of certain characters. I hope to explore this topic of sexualization further through characters such as “Lola Bunny” (Space Jam , 1996), “Roxanne” (A Goofy Movie, 1995), “Lola” (Shark Tale, 2004)... The list goes on. I also plan to discuss overt feminization in tandem with and separate from sexualization tropes.

16 notes

·

View notes

Photo

1. In the 30s, Mickey Mouse was used as a vehicle to tell mostly silly, charming, short stories appealing to an economically devastated American audience. However, most shorts of the 30s are sprinkled with violent slapstick (which is tolerable because the victims of the violence are just animals), overt gender stereotypes and prescriptive heteronormativity, and anthropocentric representation of animals. In this short alone, Mickey and Minnie drag Pluto on a leash behind their car (also anthropomorphic), Minnie has trouble keeping her skirt over her underwear when dancing with Mickey (while getting plenty of smooches in), and lastly, a hoard of “wild” animals steals the pair’s picnic food. This last example gets at something larger I want to discuss throughout the blog; what differentiates our anthropomorphized animal icons from other animals? Furthermore, because I know we’ve all thought about this, how does an anthropomorphic mouse own a dog as pet (who is only a little bigger than him), while also having another dog, who happens to wear clothes and speak, as a friend? What is the difference between Goofy and Pluto? Following the pattern of Disney’s animal character development, it would seem that the ability to wear clothes, speak, live in homes rather than holes in the ground or trees, and have white gloved hands (derived from minstrel show traditions which often included racist caricatures), transform an anthropomorphic animal into the human surrogate of the story. On the other hand, animals that are not animated to be bipedal, lack the ability to speak, do not wear clothes, and are “un-gloved”, retain their “animal-ness” and are not given the autonomy of the human surrogate animal characters.

0 notes

Photo

1. Mickey Mouse in “The Picnic”, 1930

2. Fantasia, 1940

3. Vintage T-shirt, 1980s

4. Mickey Mouse Clubhouse, 2006-2016

5. Mickey Mouse Symbol

5. “Mickey Mouse” in TsumTsum, 2014-present

6. “Mickey Mouse” in Mickey Mouse, 2013-2019

The images above illustrate the evolution of Mickey Mouse from an image, to a character, to a cultural icon, to a symbol. This evolution illustrates shifts in cultural values over the course of the past 100 years as well as animation technologies.

0 notes

Text

Frame Animation, Mickey Mouse, and the Age of the Anthropocene in America

The history of the moving image is long and varied and has roots in many different cultures. Animation is just one chapter in that history. Before the invention of photography became mainstream and relatively more accessible, there was an abundance of optical “toys” that exploited the phenomenon of the persistence of vision. This phenomenon is an optical illusion of sorts; it describes the eye’s unconscious behavior of retaining an image in the brain even after it is “gone” or removed from view. Persistence of vision is what makes devices like the phenakistoscope and the zoetrope so effective in convincing the eye that one still image replacing another, replacing another, and so on, is a moving image, rather than a collection of similar drawings.

After the invention of photography, film and animation evolved alongside each other to become what they are today; the most abundant and popular medium for advertising and entertainment. There is something so convincing and compelling about this mode of simulating reality, especially animation. Animation brings inanimate objects to life, gives animals and plants and other organisms voices, thoughts, and ideas, and is especially good at manufacturing relationships between the viewer and those characters that do not exist outside of the frame. Animation can convince a child that they need five more lego sets. It can transform the image and the idea of a lion, a bear, and even a mouse into an iconic character that millions (possibly billions) of individuals relate to and sympathize with.

The character ‘Mickey Mouse’ will serve an appropriate entry point into this broad topic of anthropomorphism in advertising and entertainment:

How has the character Mickey Mouse evolved over the decades? How do these evolutions signify cultural shifts? How has this particular animated, anthropomorphized mouse been transformed from a playful, children’s character into a symbol of a multi-billion dollar media conglomerate recognizable by silhouette alone across the globe? How do Mickey Mouse and similar characters continue to blur the line between entertainment and advertising?

0 notes

Text

Introduction

This blog is intended to analyze the history of the anthropomorphism of animals, plants, and other, non-human organisms in the context of advertising and entertainment in the 20th and 21st centuries. The strategy of anthropomorphism in advertising and entertainment (and sometimes propaganda) will be explored as a symptom of the Anthropocene, and, by extension, the Capitalocene.

Some questions this blog seeks to consider:

How and why are anthropomorphic animal characters especially effective tools for advertising?

How are anthropomorphic plants (and other organisms) less (or, in some cases, more) effective in advertising when compared to anthropomorphic animals? Why?

Is the practice of anthropomorphism a “natural” characteristic of human behavior? How long have human cultures been anthropomorphizing? What was the purpose then and how has it evolved?

How is anthropomorphism in entertainment and advertising a result of intentional “color-blindness”? In other words, how does replacing human characters with human-like animal characters protect creators from being criticized for choosing to represent one race or ethnicity over another?

How effective is the practice of anthropomorphism in dismantling anthropocentric values surrounding non-human organisms. Rather, is anthropomorphism effectively propagating and maintaining those anthropocentric views?

How does anthropomorphism maintain the Capitalocene? Is the practice of anthropomorphism intrinsic to both epochs?

How might divorcing mass media (advertising and entertainment) from the practice of anthropomorphism challenge the values of the Anthropocene and the Capitalocene? What are our alternatives moving forward?

1 note

·

View note