Text

Two Small Brecht Translations on Memorials and Statues

From Journeys into Modernity

After the great wars, my work was discovered in the vault of a fascist national library alongside other ‘degenerate literature’. An equestrian statue of me was erected on a children’s playground. I hurried along to see it.

On the whole I was satisfied with the statue. The artist had chosen to portray me with a friendly expression, which I heard had been requested in the commission. I understood that this was an honour: recognizing my friendly attitude towards coming generations.

“But why a horse?” I asked my companion.

“It indicates he dates back to antiquity,” was his answer. “And between us, there is yet another reason. Horses are completely extinct. The statue was intended to kill two birds with one stone, insofar as it also preserved the form of this animal in memory.

Undated, probably circa 1940, Werkausgabe, Vol. 19, pp. 425-426

On the conjunction of lyric poetry and architecture

A historical inquiry into the effects of art would without doubt conclude that all new effects in art appear together with transformations of consciousness, and indeed arrive together with the transformations in the economic-political base of human society.(Scenes of recognition from antiquity point to commerce and to military campaigns, just like the ‘oedipus complex’)

There are long-term consequences. Weighty experiences, which are built into “inheritances”, still trigger reactions, which are fading away, slowly, centuries later. And in a weaker, changed form, the novelties in the communal life of people are present: feudal types of relations are passed to the proletariat and the bourgeois, and so on.

The photography of the Russian Revolution - not only that of 1917, but also that of 1905 - displays a peculiar literarisation of street scenes. Cities, and indeed villages, are littered with sayings as though they were symbols. With broad brushes, the conquering classes write their opinions and slogans on conquered buildings. “Religion is the opium of the masses” is scrawled on churches. And on other buildings there are other instructions for their use. On demonstrations shields bearing inscriptions are carried; at night films appear on the walls of houses. In the Soviet Union, this literarisation has been naturalised. The year-round demonstrations, both regular and for special occasions, have formed a tradition. The working masses developed a particular type of sense of form in their emblems. At the great Mayday demonstration in ’35 I saw a beautiful emblems of a textile factory (made of white wool), narrow, lightly fluttering flags of a new form, fantastic representations of political enemies, and many slogans upon transparent banners, so that at any one time many of these slogans and pictures were visible. The qualified lyric poetry of the Soviet Union has not kept pace with the development of this mass art. The beautiful stations of the Moscow subway have enormous marble walls, which could so easily bear poems that would describe the heroism linked to their production by the population of Moscow. The same is also true for the cemetery for great revolutionaries in the Kremlin. And with the scientific institutions, sports stadiums, theatres. Their inscription could greatly elevate lyric poetry. It is their task to sing the deeds of the great generations, and to preserve their memory. The development of language from here contains its finest impulse. That those words that stone will bear have to be so carefully chosen, and will be read for a long time, and always by many people at the same time. Competitions would spur lyric poetry on to new achievements, and later generations would receive, together with the buildings, the instructions and the writings of their builders.

1935 (Werkausgabe, Vol. 19, pp. 387-388)

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Towards Pure Machines: A Benjaminian Footnote

As a young man Edgar Allen Poe wrote an essay debunking the Mechanical Turk. The famous machine had been built by Baron Kempelen in 1769, and by the end of the century it was owned by Johann Nepomuk Mälzel, who after touring it through central Europe, sold it and moved on to other ventures. By the mid-1810s Mälzel had patented the metronome. Although his patent would be contested in court, he established, by way of a machine, the intellectual rights to the measure and regulation of musical time. Mälzel also invented the panharmonicon, a mechanical orchestra. He collaborated briefly with Beethoven, who composed a piece for the contraption, while the entrepreneur created ear-trumpets to aid the great composer’s failing hearing. Yet this relationship also ended up with a court case, as Mälzel absconded with his panharmonicon and gave unlicensed performances of Beethoven’s work.

Ever the showman, Mälzel went on to repurchase the Mechanical Turk, and took it to the United States, touring it in performances. This was the context in which Poe saw the machine. Poe took cues from the likes of William Brewster (discoverer of polarized light, and inventor of the kaleidoscope, leading to a craze in 1817 and another subsequent struggle over patents). Brewster had suggested that the Turk was operated by a dwarf in the eleventh of his Letters on Natural Magic Addressed to Walter Scott. Yet unlike the enlightenment thinkers who aimed to explain away the impossibility of illusionistic effects into a mechanistic materialism, Poe was concerned otherwise. His detective-like unravelling of the Turk was aimed at the machine’s social mystery. He abhorred “the most general opinion in relation to it, an opinion too not unfrequently adopted by men who should have known better.” His deduction took aim less at the illusory quality of the machine than the apparently spurious authority of its mystery.

Poe’s essay established two possible solutions: that the Mechanical Turk was a “pure machine”, whose movements were untouched by human agency; or, that its moves were regulated by a “mind”. In propounding the latter, Poe unintentionally went on to describe a third term: the contortion of the body of the chess-player, William Schlumberger, who was concealed within the machine.

Walter Benjamin would adopt the image of the Mechanical Turk in his final work, ‘On the Concept of History’ as an allegory for history. Benjamin knew Poe’s works, as they had been translated by Charles Baudelaire. The gaslit streets of ‘The Man of the Crowd’ became the decisive image in Benjamin’s theorisation of the flâneur as noctambulist. Baudelaire also included the essay on the Mechanical Turk, under the title ‘Le joueur d’échecs de Maelzel’ in his 1857 translation Nouvelles Histoires extraordinaires.

Benjamin makes an amendment to Poe’s argument – and although this amendment is crucial to his revolutionary thought, it has been widely ignored. In Benjamin’s text the Turk “is to win all the time. It can easily be a match for anyone.” Contrarily, Poe noted that “the Automaton does not invariably win the game.” But he notes, “were the machine a pure machine this would not be the case – it would always win. The principle being discovered by which a machine can be made to play a game of chess, an extension of the same principle would enable it to win a game – a farther extension would enable it to win all games – that is, to beat any possible game of an antagonist.”

Already in Benjamin’s aphorism a dialectical reversal is staked: the hunchbacked dwarf of theology is said to be “in the service” of the apparatus called historical materialism. The machine is not some prosthesis in the service of theology’s “mind”, but rather theology has become, as Marx put it, an appendage to the machine. Yet Benjamin’s glorious and catastrophic resolution to this greatest of all ideological problems is not some vague, Romantic humanism, nor secessionism hypothesizing some other history in which the worker simply is not trapped within the machine. Instead, Benjamin proposes his own version of a “pure machine” characterised precisely by the contortion, invisibility, and anonymity within it. Theology is granted not an idea but only a stature, a posture, and an ugly physiognomy that must remain hidden.

Poe had misunderstood the machines of his time. Babbage’s Difference Engine was considered to replace the calculating of the human mind. Yet technologies of the 19th century were of a specific kind because the minds of men were concentrated on, and calculating, one thing only: the extraction of value from the labour of others. The purest of pure machines were hybrids and monsters, already worked up out of labour, and voraciously enclosing more.

This gives a clue to the peculiar visage of the Turk. Poe remarks looks like a human but does not look human. Perhaps he is a man from someplace else, persistently in the pursuit of leisure, but always set to work, forced to play out somebody else’s fantasies. So too with the world of commodities that present all-too-human desires dislocated from their bodies, already too broken in their making. So what do they make? What do we make? Sometimes entertainment, spectacles before the grand crowd. But the vision – the true vision – is otherwise. For it is broken, fragmented, half-seen from the inside and set to work at the endless game. Benjamin understood that perhaps in every moment every commodity is made and remade, but just so are made and remade the powers of destruction. That is to say, in the regulation of the time of production, so too is produced a truly historical time, whose only measure is the force of destruction, legible in the ruin of the hidden and the anonymous. This is no sublime vision. But it is with those powers, accumulated in contortion and innervation, as the human becomes the most impure of pure machines, that the game will always decisively be won.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Away with all your monuments - Thoughts on Holocaust Memorial Day from 2020

Away with all your monuments. Yet today, again, we are compelled to monumentalise. It is the 75th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz. Little liberation it was: of the 1.3 million Jews sent there, over a million were murdered. The resistance failed. What does the compulsion to monumentalise feel like? Screens everywhere littered with stories of quiet bravery in the face of fascism. Faith in the promise that history could have been otherwise. Tales of fortitude picked up like golden tickets by all those officials, who happily assure us that should fascism ever threaten again they would be on the right side. And what were those who died like? Some were good people, others bad. Some were communists, some not. Some were Zionists, others not. Some resisted. Some collaborated. Most were broken before death. And resistance often meant a quicker death too. Ultimately it made little difference, because they alike were murdered. And although many brave people across Europe risked everything to save Jews, to rescue them and smuggle them across borders, many others did nothing.

I'm scared by these stories, that deal in separating good from bad, the resistor from the collaborator. The horror of Auschwitz is of indifference. Among the victims of the Holocaust the compulsion to resist was the very same as the compulsion to collaborate. And if the lesson that is learned is that every Kapo deserved his own execution, it is no lesson at all. Today I am remembering those who, as well as resisting, did not resist, could not resist, resigned, gave in, handed over their brothers and sisters, parents, children, and comrades to fascists and were nonetheless murdered. It is a grizzly thought but one we cannot do without. Today I am remembering those who survived and who nonetheless were far from angels, whose lives were blighted and who continued to blight the lives of others. Because to become victims of fascism did not make them good either. This is not to say that those who brought the message of what happened, that those who were spared and fought to stop us forgetting, were no good.

The compulsion to monumentalise means that Auschwitz has become some fatal star of morality. The industrialised murder of Jews, of Roma, of people with disabilities, of gay people, of communists, has become an opportunity for the great and the good to distance themselves from evil. It is feel good and blindness. It has become a festival of comfort and of peace. Peace we need and comfort we do not. In making sacred the victims it remakes them into sacrifices, whether or not they were spared.

I think of the words of the great philosopher Gillian Rose, who talks about “the sentimentality of the ultimate predator” in thinking about the film Schindler’s List. She wrote, “Schindlers List betrays the crisis of ambiguity in characterisation, mythologisation and identification, because of its anxiety that our sentimentality be left intact. It leaves us at the beginning of the day, in a Fascist security of our own unreflected predation piously joining the survivors putting stones on Schindler’s grave in Israel. It should leave us unsafe, but with the remains of the day. To have that experience, we would have to confront our own fascism.” It is one of the bravest thoughts.

Today fascism again threatens. It threatens in the middle of our culture of sacralised victims. The fascism of our time has more than it would like to admit in common with the compulsion to monumentalise. It stands opposite and as mirror image of the saintly victim, as the accused. It says, “if the victim does not need to question whether they are good or bad, if their victimhood is sovereign, then I have no need to take their accusation seriously, and have no need to confront my own fascism.” But we do not need our victims to be good for the demand for justice to be righteous. Indeed justice can illuminate the world only in the redemption of those who were not already good, not already saints, not already sacralised by what was done to them. And justice does not recognise the goodness of those who were compelled to resist, as others failed. So today I resist as I affix my memory to those who did not resist. Away with all your monuments. Only then can we confront fascism, without prematurely celebrating (already 75 years too late) our anti-fascism.

(I put this up, now a year later, because I haven’t had time to write something new this year.)

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

All of capital will put on its liberal mask, and claim it is glad to be done with that man. The rich and the powerful will, for a few short weeks, pretend to rejoice with “normal folk” in their relief. But we should never stop asking, “in whose interests did he govern?” There are some who will say he governed only out of self interest, that a single ego ruled the world, and that nobody else was responsible. But the rich and the powerful, those who profiteered, those who made careers in the opinion of opposition when not opinion but force was needed, those who benefitted from the murder of black people, and those who benefitted from the scandal of the murder of black people - they will soon all go silent. Breathe your sighs of relief all you like; Trump ruled, and was allowed to rule, because autocracy and protectionism, race war and violent policing, anti-immigrant sentiment and sinophobia, the myth of profitable all-American production was of benefit to the most wealthy and powerful strata of society. He was allowed to rule because flirtations with fascism by those who call themselves liberal are a perennial aspect of the ideology of Coastal neo-liberalism, while they blame its violent excrescences, its paranoia, and its racism on those who it dupes with the economic promises of manufacture and the social promises of ethnonationalism. Things might change a little: Biden and Harris will probably be more friendly to the new monopolists, the centibillionaires, while appeasing the mere billionaires with scavenging from whatever new war in the Middle East they design. It is all very bleak.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Election and Stupidity

I am glad the election is over, because through the weeks of opportunism, integrating myself into the campaign, I have watched myself getting stupider. It has felt like lopping off, day by day, each organ of perception. Sometimes the cause of communism calls for this type of self-barbarisation: but it's also worth trying to take hold of the fucking blunted dullness that induces. It is difficult to tell if what I'm writing comes out of the stupidity or my resistance to it. Probably both.

I spent a lot of the last five weeks mixing campaigning with listening to the audiobook of The Golden Notebook. That great work of communist splitting, now remixed, now split again. Since the results came in lots of people are talking about "political education" and "community organising". I consider these to be empty concepts. They are cries of people who have realised that there is something missing in what they thought they were doing right - but those people are worst of all to find out how to fill that emptiness. I am not a vanguardist, but I will make claims for the communist avant-gardes. For histories that are for us and only us (in some secret compact between all generations). That there are these most extraordinary of works that are ours - and lots of us have our own communist canons and countercanons. I think everyone should read or listen to Lessing. Or pick up some Jelinek. Go grab some Aime Cesaire, or some Rene Menil. Go to the Blake exhibition at the Tate - and maybe a few hundred of us can go all at once and refuse to pay to go in, and we will explain that they can't stop us because Blake was a communist. Recite some Rimbaud or Ulrike Meinhof. Get with the Latin American communist poets like Huidobro or Vallejo. Perform some Brecht for your children. Go pirate some Pasolini or some Fassbinder or some Petri.

And it's not just things of the past. There continues to be this feverishly exciting, virtuosic communist production. Here's just some things I loved this years that changed how I saw the world, changed how I acted: Sophie Lewis' Full Surrogacy Now; all of Anne Boyer's writing; And all of Sean Bonney's too; Verity Spott's Click Away Close Door Say; Caspar Heinemann's Novelty Theory. And these are just people close to me, my friends and loved ones, because this fucking torrential underground is as full with the living as it is with the dead. There is so much more.

And these are - in the end - all quite simple things, often made in stolen hours or years. Simple at least compared to the world that we are collectively and perversely producing and reproducing together, with communism the perversion of the perversion (far better and more beautiful and more painful and more forceful than the negation of the negation.) We have to think the world as well, sometimes as simple as a crystal yet so full of tenderness. And that's what all these great communist avant-gardists were capable of, just as Marx was - even if in them and in their work the crystal is sometimes cracked.

Maybe that’s why I don’t like “community organising” or “political education” - because in how programmatic or awfully practical these proposals are they stamp out everything I’ve learned from these torrents of communist virtuosity. They are as mediocre as they sound, and resigned too. Someone’s gonna come on here and accuse me of intellectualism. Please instead fuck off.

What once excited me about Corbynism was the promise of a politics that wasn't just about some people in Parliament: the promise of a changed politics that changed the world, and within which the relations between politics and the world would also be changed. I think that's true for a lot of other people too. And that is long in the past now. By 2017 Corbynism was set on a course of mere parliamentarianism: the tasks established for its popular base nothing more than cheerleading through Twitter about how great they thought it all was, or reading opinion polls like tea leaves, as enthusiasts for their own good fortune. Or even worse the task became a type of collective introversion in which the committed ones built ever more baroque policy castles in the air, veritable King Ludwigs of social democracy. The two processes are conjoined: the first in which historical action is exchanged for mere spectatorship; the second in which politics is exchanged for policy, the means of social transformation exchanged for toying with the various fantastic imagined ends. What was rancid in the project was that their collective dreams - yes dreams - were things like "Keynesian deficit spending" and "a reorganisation of the benefits system" or "better public transport." And I don't decry it easily, because these are things really would help lots of people to survive who will be horribly murdered, who will suffer brutality, whose cries will be silenced. But also these are shit dreams compared to COLLECTIVELY BUILDING A WORLD OF FREEDOM, EXPLODING PAST INJUSTICE INTO HAPPINESS, THE SHAPES OF FIRE, THE UNBABBLING OF LANGUAGE INTO TONE THAT KNOWS NO PURITY OR IMPURITY, REVELATION OF THE BEAUTY OF THINGS INTHEMSELVES, THE RECONCILIATION OF NATURE AND HISTORY, THE ANNIHILATION OF CLASS SOCIETY, GLORIOUS ILLUMINATION, THE FORCE THAT STRIKES DOWN THE POWERFUL, THE END OF ALIENATION, PERPETUAL BLISS etc.

And I mean yes this is stupid and sloganistic, a sort of golden calfism that is no good without knowing at the same time that each and every one of these are diverted through the most fragile and difficult particularities of lived experience - as much through that with which we give each other strength as through how we oppress and destroy each other. And the tension is finding how other people do these things, try to say them, how we as a collective fail to be collective.

But you know how stupid it makes us not to even dream these things, not to be even lightly touched by them in every moment (or not to be able to perceive that we are already lightly touched by them). The communists disdain to conceal their views and aims. One of the worst things that can come of us is to be fooled by our own opportunism. I am slowly going to try to make myself and those around me less stupid than I have been and would like friends and comrades to help. This isn’t about Enlightenment or Bildung. This isn’t about finding agreement or any more doxasticism in this world where opinion and its parasitic monopolies has overflowed truth. It is about struggle and negativity. It is without ends. And all force to us.

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Notes to Sean Bonney (1969-2019)

The great ruse of our political epoch: Cameron, Osborne and Clegg, and their crows in press, scorched a set of oppositions in the minds of the people. The whole of society encapsulated in an image of “workers versus shirkers”, “strivers versus skivers.” The great tragedy of our political epoch: the Labour movement, the left, and the social democrats took the bait of these laminated ghouls. They responded simply by saying that there were no skivers: instead there was a worthy working class, labouring away ever harder, and getting ever poorer. They said the whole thing was a myth, that the shirkers were a phantom, a chimera, a scapegoat, an image invented by evil overlords to turn the working class against itself, leaving it prone to the ideologies of reaction. The labour movement talked instead only about the working poor, or the unemployed who wanted always to get back to a good job, on a good wage, forever and ever.

Few resisted the ruse, but Sean Bonney was one of them. Perhaps it was because Sean himself was a skiver, a drunk, a scoundrel, a villain, an addict, a down-and-out, a fuck up. More likely it was because of his deep political intuition and understanding. For him, the politics of class warfare was never about worthiness; it was never about what the working class deserve at the end of a hard day’s work, but instead its crucible was the hatred of the social conditions that pummelled people, silenced them, boxed them in, boxed them up, oppressed them, made them suffer. This politics was uncompromising because it understood that any compromise was a failure: there is no weekend that redeems the week, no pension that makes good on the life wrecked by the conformity and unfreedom of work.

I like to think of Sean as the thing that terrified those Tories most, as one of those beautiful creatures who so absolutely threatened them that they had to transfigure him into a phantom. His poetry too was one with this politics in this. Every line is written in solidarity with the shirking class, a class whose underground history crawls and stretches backwards, a perpetual dance, an unending squall, as anonymous as it is enormous. If Sean was a skiver he was also always hard at work, undertaking an immense labour of compression, in order to make that history heard. And this furious labour was quick and angular, because it always came with some sense that history was, already, ending. As a singular voice that resisted the ruse, his writing is one of the most important political efforts of our time.

o scroungers, o gasoline

there’s a home for you here

there’s a room for your things

me, I like pills / o hell.

***

Since hearing of Sean’s death I have been thinking a lot about what I learnt from him. Learning is maybe a strange way to look at it. Because Sean’s poetry was not really so complicated. He stated unambiguous truths that we all knew and understood. Just like Brecht’s dictum in praise of communism: “It’s reasonable, and everyone understands it, it’s easy […] it is the simplicity, that’s hard to achieve.” This was the plane on which we met. All of us, Sean’s friends, comrades, loves, beloveds, others we did not know who all were invited, all in this common place where we know how simple these truths are, even if none of us were able to express them with such concision as Sean – even if we were all somehow less rehearsed, less prepared, less audacious. And suddenly I know it was a common place he made, wretched and hilarious.

***

So communism is simple. But running beneath all of Sean’s work was an unassuming argument, from which I have learned so much. Although argument was not his mode – his poems were always doing something, accusing but never prosecuting – an argument is there, even if it was exposed as a thesis in its own right. It is something so simple, easy, and so obvious that it barely seems worth saying. Sean’s poems made an argument for the enduring power of French symbolism – for a power that surged through history in the spirit of that movement. No surprise for a poet who rewrote Baudelaire and Rimbaud. But constantly a surprise to a world that thought that mode already dead, a world no longer animated by the literary symbol, nor transfixed by the resurrection any such symbols could herald. His writing followed the traces of this hyperhistory that wrapped around the world and back, from the high culture of decolonial revolutionism back in to cosmopolitan centre where bourgeois savages feast greedily on expropriated wares; into the dark sociality of the prison, and out again into every antisocial moment that we call “society”; sometimes making the earth small within a frozen cosmos ringing out noise as signal to nobody and everyone; sometimes bringing the whole cosmos in crystalline shape (sometimes perfect, sometimes fractured) as the sharpest interruption within the world - every poem charting a history stretched taut between uprisings and revolts. He knew the rites of symbols, the continuing practices with which their political power could be leveraged.

Sean was one of the few untimely symbolists of our time. His poems are full of these things: bombs, mouths, wires, bones, birds, walls, suns, etc - never quite concepts, never quite images, never quite objects, but pieces of the world to be taken up and arranged, half exploded, into accusations; treasured as partial and made for us to take as our own, a heritage of our own destruction, at once ready at hand, and scattered to the peripheries on a map of the universe, persistently spiralling, in points, back to the centre, some no place.

But if Sean was a symbolist, if he was attentive to its fugitive history, a slick and secret tradition of the oppressed, then this was also a symbolism without any luxuriant illusion. It is a symbolism in which all knowingness has been supplanted with fury and its movements. Sean’s poems are spleen without ideal. They have nothing of the pointed, almost screaming, eternal sarcasm of Baudelaire when he ever again finds the body of his beautiful muse as white and lifeless cold marble, utterly indifferent to the desirous gaze. There is no such muse, no callous petrified grimace, half terrified half laughing, ancient enough to unseat Hellenism itself - although there is beauty still but it exists otherwise, amid a crowd, darkened and lively. When I think of Sean’s monumental work I imagine an enormous bas-relief of black polished marble jutting out from some monstrously disproportioned body, angled between buildings. This great slab flashing black in the white noise of the city. This great slab as populous as the world. Flashing black and seen with the upturned gaze. There is no oppression without this terrified vision that sees in ever new sharpness the oppressor.

When you go to sleep, my gloomy beauty, below a black marble monument, when from alcove and manor you are reduced to damp vault and hollow grave;

when the stone—pressing on your timorous chest and sides already lulled by a charmed indifference—halts your heart from beating, from willing, your feet from their bold adventuring,

when the tomb, confidant to my infinite dream (since the tomb understands the poet always), through those long nights in which slumber is banished,

will say to you: "What does it profit you, imperfect courtisan, not to have known what the dead weep for?" —And the worm will gnaw at your hide like remorse.

***

I haven’t explained what I learnt. I ask the question, What does it mean to find the late nineteenth century stillborn into the twenty-first? Why should these febrile years, from 1848 to the Commune have been so important? What was Sean leveraging when he recast our world with this moment of literary and political history? And what was he leveraging it against? I have a sense that what was important to Sean was a sense of mixedness. There were those who would read these years, after the defeat of revolution, as a dreadful winter of the world. There were those who saw only society in decline. “Jeremiads are the fashion”, Blanqui would say while counselling civil war. And then there were those for whom arcades first provided an extravagant ecstacy of distraction and glitz. These were the years of monstrocity, from Maldoror to Das Kapital. These years of the great machines that chewed up humans and spat out their remains across the city, of great humans who chewed up machines and made language anew. These years in which the fury of defeat burnt hot. These years of illumination. These years where gruesome metallic grinding and factory fire met the dandy. Few eras have been so mixed, so utterly undecided. No era so perfect to carve out the truly Dickensian physiognomy of Iain Duncan Smith. This was neither the stage of tragedy nor comedy, but of frivolous wickedness and hilarious turpitude. The world made into a barb, and no-one quite knowing who is caught on it. The great progress. The great stupidity. Street life. The symbol belonging to this undecided realm.

Marx was famously dismissive of that “social scum” the Lumpenproletariat, who he described at the beginning of this period as “vagabonds, discharged soldiers, discharged jailbirds, escaped galley slaves, swindlers, mountebanks, lazzaroni, pickpockets, tricksters, gamblers, maquereaux, brothel keepers, porters, literati, organ grinders, ragpickers, knife grinders, tinkers, beggars — in short, the whole indefinite, disintegrated mass, thrown hither and thither, which the French call la bohème.” Marx saw in these figures, in their Bonapartist, reactionary form, a bourgeois consciousness ripped from its class interest and thus nourished by purest political ideology. But if he could excoriate the drunkenness of beggars, Marx failed to appreciate its complement: the intoxication of sobriety of the working classes, the stupefaction in methodism, their imagined glory in progress. Wine, as the beggars already knew, was the only salve to the social anaesthetic of worthiness and the idiotic faith in work.

If Sean were here I’d want to talk to him about this learning in relation to a fragment by Benjamin, which he wrote as he thought about the world of Baudelaire; this world of mixedness of the city constructed and exploded, and the people within it subject to the same motion:

During the Baroque, a formerly incidental component of allegory, the emblem, undergoes extravagant development. If, for the materialist historian, the medieval origin of allegory still needs elucidation, Marx himself furnishes a clue for understanding its Baroque form. He writes in Das Kapital (Hamburg, 1922), vol. 1, p. 344: "The collective machine ... becomes more and more perfect, the more the process as a whole becomes a continuous one — that is, the less the raw material is interrupted in its passage from its first phase to its last; in other words, the more its passage from one phase to another is effected not only by the hand of man but by the machinery itself. In manufacture, the isolation of each detail process is a condition imposed by the nature of division of labor, but in the fully developed factory the continuity of those processes is, on the contrary, imperative." Here may be found the key to the Baroque procedure whereby meanings are conferred on the set of fragments, on the pieces into which not so much the whole as the process of its production has disintegrated. Baroque emblems may be conceived as half finished products which, from the phases of a production process, have been converted into monuments to the process of destruction. During the Thirty Years' War, which, now at one point and now at another, immobilized production, the "interruption" that, according to Marx, characterizes each particular stage of this labor process could be protracted almost indefinitely. But the real triumph of the Baroque emblematic, the chief exhibit of which becomes the death's head, is the integration of man himself into the operation. The death's head of Baroque allegory is a half-finished product of the history of salvation, that process interrupted — so far as this is given him to realize — by Satan.

I won’t pretend to know all of what Benjamin means here but I have some idea. And those last sentences terrify me. Modernity begins with a war that is a strike, one that repeats through history. And the shape of this strike, this war, this repetition, is the shape of detritus of production interrupted. We shift perspective and the machine is revealed as other than it was once imagined: it is not some factory churning out commodities, but a world theatre of soteriology. An exchange takes place: the half-finished product for the half-destroyed body. Although what is created (albeit as a “monument to the process of destruction”) is some monstrous combination of the two. One and the same seen with two different perspectives, and the two perspectives separated by the distance between the promise that production will be interrupted, in rhythmic repetition, and the force of the machine that completes the product, kills the body into it, sealing death perfectly within the commodity, as its catastrophe. This distance, a tropic on the edge of the end of the world, is Hell.

This is a lot. But maybe it gets close to what I learnt. That all those bombs, mouths, wires, bones, birds, walls, suns, etc were for Sean the emblemata of our political times. These are the monsters, half-finished, half-human, half-machine, the bird interrupting itself with a scream a silent as the cosmos once seemed. I don’t know if they are to be taken up as weapons in the battle for salvation, or as mere co-ordinates on the map of hell. But they are certainly potent, and set here in commitment to redemption, for the work of raising the dead. Sean’s writing was always ready for this task, in constant preparation, and in constant interruption. Its angles quickly pacing between the two.

This has become theologically ornate. But perhaps something of the point is clear: that in the symbolic realm of Sean’s language are staked the great theological and materialist battles of our age. He had to deep dig into our time for that, furrow and dig so deep that he found the nineteenth century still there, crawling everywhere, right up to us. And all of this was set, furiously, against a more everyday view that production has all but disappeared from sight: society fully administered slips across screens with nothing but a sense of speed and gloss. His poetry decries, digs into, a laminated world with which we are supposed to play but in which we are never supposed to participate, never mind to get drunk, see the truth, raise the dead, even now as they slip away ever further through the mediatized glare.

***

Are we not surrounded by those who cast spells? Sorcery is the fashion, if only for the blighted, the meek, the poor, the oppressed. And it would be easy to mistake what Sean was writing for just another piece of subaltern superstition; promising mighty power for as long as it remains utterly powerless and otherworldly. But this is not right. Seans symbols are not just any old sign, or signal, or sigil. They are not arcana, but materials taken to hand out of the dereliction of the present. They are certainly magic, just as Sean was certainly a seer. But this is a materialist magic, a fury, a joy. They are not drawn from some other mystical world, but from this one. And his magic was to suspend them between this world and the next, between law made in the mouths of a class who hated him, and justice. He saw more deeply than most of us dare, and invited us along. Invited everyone along, including the dead who will rise, even if we have to dig and dig and drag them out of the ground and through the streets, to show the world what streets are really for. Here in this common place, between buildings, together. This is the place of magic, for riots, for burning cars; here a wall, there a blazing comet. Let his poetry dance on, and we will dance on too.

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

Oppression and Persecution

A central problem of radical politics today is the confusion of oppression with persecution. Often the malign volition of the oppressor has been elevated to the highest question of why and how oppression happens. The fact that oppression operates upon a subject that increasingly recognises itself as an individual (or that oppression operates through the processes of individualisation), leads to the fallacy of believing that the oppressor must be an individual too. Political analysis is truncated in the Nietzschean or Schmittian ideological nonsense that the oppressor and oppressed, the friend and the enemy, are in some way mirror images, similarly constituted, equal partners in the terrible dance. The subject-centric thought cannot help but see only subjects everywhere. It leads ultimately to a sort of thinking that seems doomed to paranoia, in which oppressors appear only as gremlins and tormentors, creatures of sheer unhinged force without real interest, heartless and brutal. With the diagnosis of evil and the acknowledgement of antagonism the analysis concludes. This misinterpretation of material disadvantage as persecution is also the point at which elements of the new far right has most effectively appropriated left narratives. Surely a straight line may be drawn between the madness of Judge Schreber, who feared mystical rays causing his feminisation, and the online incel who takes up arms against the innocent women he claims have slighted him. Yet his fantastical theory of persecution made universal is truly not so far from what some left politics has become.

At the same time, real material conditions of persecution have lost their moral force. Every moment of supreme indignity is supposed to be explained away with sociological judgement. The young black man who is picked on by police, stopped and searched, framed and fitted up, week after week, is invited to accept "institutional racism" as an explanatory panacea. The woman degraded by men in her workplace and refused equal employment or wages, the asylum seeker deported and separated from their family, the benefits claimant who is “sanctioned” by a bureaucrat, are asked to hope that an account of “structural oppression” will adequately describe what they experience. The society that has lost all shame about its brutality expects its victims to feel no shame either, permitting no responsibility, while robbing people of the vital force in the demand for social transformation in their lives. The disenchantment implied by the sure-footedness of these theoretical abstractions is nothing but the devaluation of the subjective moment of suffering and indignity.

None of this is to say that we should conclude the analysis of society with either a theory of oppression or one of persecution. But in such a situation, it is worth asking whose interest is served by this sort of ideological confusion, in which subjects have already become objects and objects have already become subjects. This hocus-pocus conjures a cloud over the broken middle, obscuring any thinking of the transformations from subject to object and from object to subject as social processes. It condemns us on the one hand to be endlessly frustrated lunatics pointing fingers at the ever-fading mirages of evil overlords, and on the other hand to be mere scientists offering a steely gaze at our own collective demise.

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Language of Boris: Part 2

“Prison spaces”

Boris Johnson chose to announce his flagship “law and order” policies in the Mail on Sunday, a paper in which comment tends from “lock them up and throw away the key” to “bring back hanging”, with every brutal fantasy of corporal punishment getting a frequent airing too. Johnson made a promise of an extra “10,000 spaces in our prisons”. This curious euphemism is meant to highlight funding going towards a half-crumbling, half-privatised prison estate, within which prisoners are subject to all manner of abuse, violence, neglect, and overcrowding. “10,000 spaces in our prisons” sounds like the rare pleasure of being able to afford a house with a spare room. But the political calculation is otherwise: that Johnson can make himself popular with several million people by promising to send tens of thousands of other people to prison. Only, to promise of future incarceration of so many people, who have not yet committed any crimes, looks a little too much like promising some ritual sacrifice to ward off the evils of the present. As though the goat will appreciate a new shiny altar as it’s led to its death.

“The Public”

Alongside a programme of expanded mass incarceration, he announced the extension of stop and search powers across over 40 cities in an attempt to soothe the public’s worries about increases in knife crime. There he wrote,

“I want the criminals to be afraid – not the public.”

The division is stark. “Criminals” and “the public” are held firmly apart. Separation is the entire logic of this juridical strategy: criminals must be distanced from the public not only rhetorically but in reality too. It is a carceral logic, one that wagers on punishment over remedy, while knowing that the most severe punishment - the most gratifying punishment it can offer to those who yearn for “law and order” - is excommunication from the body politic.

Such a sentence also contains three dubious implications: firstly that on committing a crime you can expect not to be considered a member of the public, and that politicians no longer have any duty to serve you; secondly, only those who are not criminals themselves can be expected to be protected from crime, or to have their fears addressed by the state; and thirdly that those subject to the force and violence of these expanded tactics are already “criminals”. The last of these suggestions is particularly spurious given that the powers being offered to police officers allow stopping and searching a person “whether or not he has any grounds for suspecting that the person or vehicle is carrying weapons or articles of that kind.”

Policies such as this are not about making the public less afraid, but more afraid. Throughout his campaign to become Prime Minister, Boris falsely proclaimed knife crime as the core violence in our society. The effect was to make middle class rural and suburban white people afraid of young black urban boys and men. He reinvented the “folk devil” of black urban youth, in order to terrify people who live miles away from any urban centre, and who have little understanding of the everyday lives of people who inhabit them - lives as much full of joy as hardship, as full of striving as of difficulty, as full of fruitful collectivity and solidarity as they are subject to forces of division and competition. It’s the same as how, during the Brexit referendum, fear of immigrants was whipped up in those places where no immigrants live.

Yet victims of knife crime are not middle class white suburban Daily Mail readers, but instead predominantly young urban boys and men, most of them people of colour, poor, deprived, brutalised by society and the state, living in a world in which any aid and support has been cut away. Far from protecting young black urban boys, who are truly the victims of knife crime, far from making their lives safer, this policy will embolden racist police officers and institutionally racist police forces to attack them. Precisely those who need protecting are cast through presupposition as “the criminals” and not “the public.” All the while those middle class white folk will feel a little safer. But they don’t feel safer because they are less afraid: they feel safer because they are more afraid, and can now proclaim that something is being done about it. Never mind if that something is arbitrary violence, surveillance, harassment and criminalisation of racialised sections of the public, who are already the true victims of the violence whose fear they adopt. Never before has vicarious feeling been so craven. Like the old image of a person looking from safety out of their window at the violence of a storm, Boris’s exercise in bourgeois sublimity aims not to alleviate fear but to politicise it.

And this is without mentioning that as a police tactic “stop and search” not only does not work, but has a monumentally chequered history. These powers have long been used by racist police officers and institutionally racist police forces to target and harass young black people. The section 60 powers that are to be used more frequently were (apparently) designed as a response to violent crimes involving weapons, but 97% of stops made under the act result in no prosecution for charges involving violent crimes or weapons. By far the most arrests after a search are for minor non-violent crimes, and even more stops and searches result in no action at all. At present black people in England and Wales are 40 times more likely to be stopped and searched by the police than white people are.

The expansion of Section 60 powers has its own dubious history. The act has slippery wording in which its powers can be enforced in “any locality” in which violence has occurred or is likely to occur: during the riots in 2011, caused by the arbitrary police killing of a young black man in Tottenham, a section 60 was put in place across the whole of London (the largest area over which such an order has been put in place.) Expand the definition of “locality” enough and you can always map an area in which some violence has taken place. Then bring out the white hordes, holding brooms aloft triumphant, and say to the police, “go forth and brutalise.”

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Language of Boris: Week 1

"Golden Age”

On 25 July 2019, Johnson set out his plans in his statement on priorities for the government. The conceit of his speech was to shuttle between the pragmatics of policy and governance, via panegyrics to optimism and a can-do attitude, to an image of Great Britain in 2050. This is the date when, according to current plans, the UK’s net carbon emissions will be reduced to zero. His speech closed,

There is every chance that in 2050, When I fully intend to be around, though not necessarily in this job we will look back on this period, this extraordinary period, as the beginning of a new golden age for our United Kingdom.

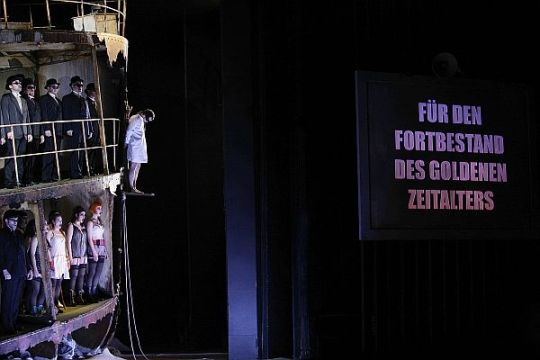

The irony is lost on Johnson: that the image of a “golden age” has always furnished societies that see themselves in decline. The golden age is an image projected back from the wreckage of a fallen, broken world. And so just as Johnson elevates his moment of election, he presages the catastrophe to come. Brecht knew this irony best: during the finale of The Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny, as the city of cartels and rackets collapses, as crooks escape and the innocent are damned by a drunken God, there enters a crowd. The people stomp out a herald of a new authoritarian order, bearing placards: “FOR THE EXPROPRIATION OF OTHERS”; “FOR LOVE”; “FOR THE VENALITY OF LOVE”; “FOR PROPERTY”; “FOR THEFT”; FOR THE WAR OF ALL AGAINST ALL”; “FOR THE FREEDOM OF THE RICH”; “FOR COURAGE IN THE FACE OF THE WEAK”; “FOR THE ENDURANCE OF THE GOLDEN AGE.”

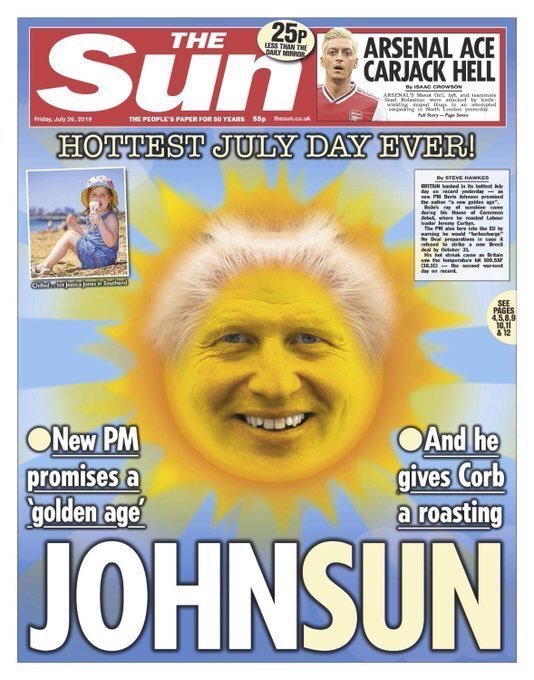

Perhaps Johnson evokes something more everyday though. This is a golden age of a golden man: fair in complexion, with a signature head of blazing yellow hair. The Sun adopts the line: its front page headline reads “JOHNSUN” depicting the new prime minister as the face of the sun, like the baby from the Teletubbies, beaming across the sky on the hottest day of the year. The opportunity to reiterate the paper’s title, to prove that it is their prime minister, is not missed. It was the oldest image of a golden age, that given by Hesiod in the Works and Days, that described it as time of in which a race of golden people lived. But by the time of Plato such an anatomic image had become untenable. In the Cratylus dialogue, Socrates argued that those who lived in the golden age were not described as as a golden race because they were truly golden in visage, but because they were good and fine. Johnson, openly deceitful and ignoble, machiavellian and brutish, could never be described as good and fine, nor wise and knowing, as Socrates continues. So roll back Plato and Socrates, back to the older racial implication, where blond hair and a fair face are the guarantors of righteousness and a world of plenty.

“Talent”

“We will also ensure that we continue to attract the brightest and best talent from around the world”: To describe a person or a set of people as “talent” has a very specific set of meanings in British English. It is not the same as describing someone as talented, or saying that they have talent, or even that they have a particular talent. Calling someone “talent” is part of a grammatical formation peculiar to the dialects of the highest upper classes (perhaps the only other word that suffers this fate is “wit”, invoked only by one upper class person convivially describing another.) The grammar involves a ricochet, firstly from a human attribute to an abstract noun, and then back as a concretion, in which this “talent” describes the whole of a person. Perhaps this motion is why describing people as “talent” has a sexual aspect too, especially when uttered in the plummy accents of the ruling classes. “Talent” means people with prominent sexual features. But we know that it isn’t the protuberances that the ruling classes love; instead what excites their libidos is the abstraction. Not least when the very notion of “talent” is designed to discover such an abstraction as naturally embedded within the body of the person thus described.

“Recovery”

“to recover our natural and historic role as an enterprising, outward-looking and truly global Britain, generous in temper and engaged with the world”: It used to be said that the sun never sets on the British Empire. 35 years since its end, nearly half of the British population remains proud of British colonialism, from the slave trade to Bengal Famine, while less than a quarter regret this history. No wonder then that Boris could help but fantasise its restoration, with every brutality recast as generosity. Such is the British character.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Fed up” and “Disappointed”: A Political Portrait of the UK

Half the population is "fed up." To express being "fed up" means to be a middle aged man, and to shout a lot (so lots of fed up people, who are neither men nor loud nor middle aged have no way to express what they want in public.) Often you are fed up because you have bad wages, or your business wasn't profitable, or because they stopped you beating up your wife and children. Sometimes you're fed up because you're not allowed to hate Johnny Foreigner any more (even though you did lose your job when new people moved to your town.) You're fed up because the NHS isn't working and no-one listens to you, but you are sure that people should be listening to you. You know that being "fed up" is all you can do to change things. And at least shouting makes you feel better. You shout because you know you're right, just like Jeremy Clarkson or Piers Morgan knows he's right, because other people are wrong. Why is no-one listening?

The other half is "disappointed." To be disappointed also means to be middle aged, or to be a millennial who dreams of being middle aged. You are disappointed mainly because of what the "fed up" people have done to you, and often because of how the "fed up" people express themselves. But nonetheless you'll still take their rent (paid for with housing benefits), increase it every year, and let the "fed up" people take the flack for the increasing cost to the public when they are called "scroungers". You are disappointed by the service at the NHS but you might have health insurance with work. You are disappointed because you worry about how the future might stop your children excelling, but you don't give a thought to other people's children left behind (just like you were disappointed when your kids only got into their second choice school, but you did nothing to change the system in which some people had to go to bad schools. No wonder, your kids will be fine even if you have to bring in a private tutor to help them a little.) You are disappointed because, when you think really hard about what a good person you are, and how you deserve all you have, you can only imagine how unkind those who have less than you must be. You are disappointed at them being fed up. Why can't they just hold a banner or sign a petition? You think a lot about how you could never be that unkind. You are disappointed that the world is unfair, but you are certain that it isn't your fault. You would never hate foreigners, but all the ones you know are well off. Why would anyone hate them? They're good and kind people too. You are disappointed that people are less worldly than you because they don't speak French, but you wouldn't learn even a word of Turkish to speak to your neighbour.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Conversation with David Panos about The Searchers

The Searchers by David Panos is at Hollybush Gardens, 1-2 Warner Yard London EC1R 5EY, 12 January – 9 February 2019

There is something chattering. Alongside a triptych a small screen displays the rhythmic loop of hands typing, contorting, touching, holding. A movement in which the artifice strains between shuddering and juddering. Machinic GIFs seem to frame an event which may or may not have taken place. Their motions appear to combine an endless neurotic repetition and a totally adrenal pumped and pumping tension, anticipating confrontation.

JBR: How do the heavily stylised triptych of screens in ‘The Searchers’ relate to the GIF-like loops created out of conventionally-shot street footage?

DP: I think of the three screens as something like the ‘unconscious’ of these nervous gestures. I’m interested in how video compositing can conjure up impossible or interior spaces, perhaps in a way similar to painting. Perhaps these semi-abstract images can somehow evoke how bodies are shot through with subterranean currents—the strange world of exchange and desire that lies under the surface of reality or physical experience. Of course abstractions don't really ‘inhabit’ bodies and you can’t depict metaphysics, but Paul Klee had this idea about an aesthetic ‘interworld’, that painting could somehow reveal invisible aspects of reality through poetic distortion. Digital video and especially 3D graphics tend to be the opposite of painting—highly regimented and sat within a very preset Euclidean space. I guess I’ve been trying to wrestle with how these programs can be misused to produce interesting images—how images of figures can be abstracted by them but retain some of their twitchy aliveness.

JBR: This raises a question about the difference between the control of your media and the situation of total control in contemporary cinematic image making.

DP: Under the new regimes of video making, the software often feels like it controls you. Early analogue video art was a sensuous space of flows and currents, and artists like the Vasulkas were able to build their own video cameras and mixers to allow them to create whole new images—in effect new ways of seeing. Today that kind of utopian or avant-garde idea that video can make surprising new orders of images is dead—it’s almost impossible for artists to open up a complex program like Cinema 4D and make it do something else. Those softwares were produced through huge capital investment funding hundreds of developers. But I’m still interested in engaging with digital and 3D video, trying to wrestle with it to try and get it to do something interesting—I guess because the way that it pictures the world says something about the world at the moment—and somehow it feels that one needs to work in relation to the heightened state of commodification and abstraction these programs represent. So I try and misuse the software or do things by hand as much as possible, and rather than programming and rendering I manipulate things in real time.

JBR: So in some way the collective and divided labour that goes into producing the latest cinematic commodities also has a doubled effect: firstly technique is revealed as the opposite of some kind of freedom, and at the same time this has an effect both on how the cinematic object is treated and how it appears. To be represented objects have to be surrounded by the new 3D capture technology, and at the same time it laminates the images in a reflected glossiness that bespeaks both the technology and the disappearance of the labour that has gone into creating it.

DP: I’m definitely interested in the images produced by the newest image technologies—especially as they go beyond lens-based capture. One of the screens in the triptych uses volumetric capturing— basically 3D scanning for moving image. The ‘camera’ perspective we experience as the viewer is non-existent, and as we travel into these virtual, impossible perspectives it creates the effect of these hollowed out, corroded bodies. This connects to a recurring motif of ‘hollowing out’ that appears in the video and sculpture I’ve been making recently. And I have a recurring obsession with the hollowing out of reality caused by the new regime of commodities whose production has become cut to the bone, so emptied of their material integrity that they’re almost just symbols of themselves. So in my show ‘The Dark Pool’ (Hollybush Gardens, 2014) I made sculptural assemblages with Ikea tables and shelves, which when you cut them open are hollow and papery. Or in ‘Time Crystals’ (Pumphouse Gallery, 2017) I worked with clothes made in the image of the past from Primark and H&M that are so low-grade that they can barely stand washing. We are increasingly surrounded by objects, all of which have—through contemporary processes of hyper-rationalisation and production—been slowly emptied of material quality. Yet they have the resemblance of luxury or historical goods. This is a real kind of spectral reality we inhabit.

I wonder to myself about how the unconscious might haunt us in these days when commodities have become hollow. Might it be like Benjamin’s notion of the optical unconscious, in which through the photographic still the everyday is brought into a new focus, not in order to see what is behind the veil of semblance, but to see—and reclaim for art—the veiling in a newly-won clarity.

DP: Yes, I see these new technologies as similar, but am interested in how they don't just change impact perception but also movement. The veiled moving figures in ‘The Searchers' are a strange byproduct of digital video compositing. I was looking to produce highly abstract linear depictions of bodies reduced to fleshy lines, similar to those in the show and I discovered that the best way to create these abstract images was to cover the face and hands of performers when you film them to hide the obvious silhouettes of hands and faces. But asking performers to do this inadvertently produced a very peculiar movement—the strange veiled choreography that you see in the show. I found this footage of the covered performers (which was supposed to be a stepping stone to a more digitally mediated image, and never actually seen) really suggestive— the dancers seem to be seeking out different temporary forms and they have a curious classical or religious quality or sometimes evoke a contemporary state of emergency. Or they just look like absurd ghosts.

JBR: In the last hundred years, when people have talked about ghosts the one thing they don’t want to think about is how children consider ghosts, as figures covered in a white sheet, in a stupid tangible way. Ghosts—as traumatic memories—have become more serious and less playful. Ghosts mean dwelling on the unfinished business of the past, or apprehending some shard of history left unredeemed that now revisits us. Not only has no one been allowed to be a child with regard to ghosts, but also ghosts are not for materialists either. All the white sheets are banished. One of the things about Marx when he talks about phantoms—or at least phantasmagorias—is much closer to thinking about, well, pieces of linen and how you clothe someone, and what happens with a coat worked up out of once living, now dead labour that seems more animate than the human who wears it.

DP: Yes, I’ve been very interested in Marx’s phantasmagorias. I reprinted Keston Sutherland’s brilliant essay on how Marx uses the term ‘Gallerte’ or ‘gelatine’ to describe abstract labour for a recent show. Sutherland highlights a vitalism in Marx’s metaphysics that I’m very drawn to. For the last few years I’ve been working primarily with dancers and physical performers and trying to somehow make work about the weird fleshy world of objects and how they’re shot through with frozen labour. I love how he describes the ‘wooden brain’ of the table as commodity and how he describes it ‘dancing’—I always wanted to make an animatronic dancing table.

JBR: There is also a sort of joyfulness about that. The phantasmagoria isn’t just scary but childish. Of course you are haunted by commodities, of course they are terrifying, of course they are worked up out of the suffering and collective labour of a billion bodies working both in concert and yet alienated from each other. People’s worked up death is made into value, and they all have unfinished business. But commodities are also funny and they bumble around; you find them in your house and play with them.

DP: Well my last body of work was all about dancing and how fashion commodities are bound up with joy and memory, but this show has come out much bleaker. It’s about how bodies are searching out something else in a time of crisis. It’s ended up reflecting a sense of lack and longing and general feeling of anxiety in the air. That said I am always drawn to images that are quite bright, colourful and ‘pop’ and maybe a bit banal—everyday moments of dead time and secret gestures.

JBR: Yes, but they are not so banal. In dealing with tangible everyday things we are close to time and motion studies, but not just in terms of the stupid questions they ask of how people work efficiently. Rather this raises questions of what sort of material should be used so that something slips or doesn’t slip—or how things move with each other or against each other—what we end up doing with our bodies or what we end up putting on our bodies. Your view into this is very sympathetic: much art dealing in cut-up bodies appears more violent, whereas the ruins of your abstractions in the stylised triptych seem almost caring.

DP: Well I’m glad you say that. Although this show is quite dark I also have a bit of a problem with a strain of nihilist melancholy that pervades a lot of art at the moment. It gives off a sense of being subsumed by capitalism and modern technology and seeing no way out. I hope my work always has a certain tension or energy that points to another possible world. But I’m not interested in making academic statements with the work about theory or politics. I want it to gesture in a much more intuitive, rhythmic, formal way like music. I had always made music and a few years back started to realise that I needed to make video with the same sense of formal freedom. The big change in my practice was to move from making images using cinematic language to working with simultaneous registers of images on multiple screens that produce rhythmic or affective structures and can propose without text or language.

JBR: The presentation of these works relies on an intervention into the time of the video. If there is a haunting here its power appears in the doubled domain of repetition, which points both backwards towards a past that must be compulsively revisited, and forwards in convulsive anticipatory energy. The presentation of the show troubles cinematic time, in which not only is linear time replaced by cycles, but also new types of simultaneity within the cinematic reality can be established between loops of different velocities.

DP: Film theorists talk about the way ‘post-cinematic’ contemporary blockbusters are made from images knitted together out of a mixture of live action, green-screen work, and 3D animation. I’ve been thinking how my recent work tries to explode that—keep each element separate but simultaneous. So I use ‘live’ images, green-screened compositing and CGI across a show but never brought together into a naturalised image—sort of like a Brechtian approach to post-cinema. The show is somehow an exploded frame of a contemporary film with each layer somehow indicating different levels of lived abstractions, each abstraction peeling back the surface further.

JBR: This raises crucial questions of order, and the notion that abstraction is something that ‘comes after’ reality, or is applied to reality, rather than being primary to its production.

DP: Yes good point. I think that’s why I’m interested in multiple screens visible simultaneously. The linear time of conventional editing is always about unveiling whereas in the show everything is available at the same time on the same level to some extent. This kind of multi-screen, multi-layered approach to me is an attempt at contemporary ‘realism’ in our times of high abstraction. That said it’s strange to me that so many artworks and games using CGI these days end up echoing a kind of ‘naturalist’ realist pictorialism from the early 19th Century—because that’s what is given in the software engines and in the gaming-post-cinema complex they’re trying to reference. Everything is perfectly in perspective and figures and landscapes are designed to be at least pseudo ‘realistic’. I guess that’s why you hear people talking about the digital sublime or see art that explores the Romanticism of these ‘gaming’ images.

JBR: But the effort to make a naturalistic picture is—as it was in the 19th century—already not the same as realism. Realism should never just mean realistic representation, but instead the incursion of reality into the work. For the realists of the mid-19th century that meant a preoccupation with motivations and material forces. But today it is even more clear that any type of naturalism in the work can only serve to mask similar preoccupations, allowing work to screen itself off from reality.

DP: In terms of an anti-naturalism I’m also interested in the pictorial space of medieval painting that breaks the laws of perspective or post-war painting that hovered between figuration and abstraction. I recently returned to Francis Bacon who I was the first artist I was into when I was a teenage goth and who I’d written off as an adolescent obsession. But revisiting Bacon I realised that my work is highly influenced by him, and reflects the same desire to capture human energy in a concentrated, abstracted way. I want to use ‘cold’ digital abstraction to create a heightened sense of the physical but not in the same way as motion capture which always seems to smooth off and denature movement. So the graph-like image in the centre of the triptych (Les Fantômes) in this show twitches with the physicality of a human body in a very subtle but palpable way. It looks like CGI but isn’t and has this concentrated human life force rippling through it.

If in this space and time of loops of the exploded unstill still, we find ourselves again stuck in this shuddering and juddering, I can’t help but ask what its gesture really is. How does the past it holds gesture towards the future? And what does this mean for our reality and interventions into it.

JBR: The green-screen video is very cold. The ruined 3D version is very tender.

DP: That's funny you say that. People always associate ‘dirty’ or ‘poor’ images with warmth and find my green-screen images very cold. But in the green-screened video these bodies are performing a very tender dance—searching out each other, trying to connect, but also trying to become objects, or having to constantly reconfigure themselves and never settling.

JBR: And yet with this you have a certain conceit built into the drapes you use: one that is in a totally reflective drape, and one in a drape that is slightly too close to the colour of the greenscreen background. Even within these thin props there seems to be something like a psychological description or diagnosis. And as much as there is an attempt to conjoin two bodies in a mutual darkness, each seems thrown back by its own especially modern stigma. The two figures seem to portray the incompatibility of the two poles established by veiled forms of the world of commodities: one is hidden by a veil that only reflects back to the viewer, disappearing behind what can only be the viewer’s own narcissism and their gratification in themselves, which they have mistaken for interest in an object or a person, while the other clumsily shows itself at the very moment that it might want to seem camouflaged against a background that is already designed to disappear. It forces you to recognise the object or person that seems to want to become inconspicuous. And stashed in that incompatibility of how we find ourselves cloaked or clothed is a certain unhappiness. This is not a happy show. Or at least it is a gesturally unsettled and unsettling one.

DP: I was consciously thinking of the theories of gesture that emerged during the crisis years of the early 20th century. The impact of the economic and political on bodies. And I wanted the work to reflect this sense of crisis. But a lot of the melancholy in the show is personal. It's been a hard year. But to be honest I’m not that aligned to those who feel that the current moment is the worst of all possible times. There’s a left/liberal hysteria about the current moment (perhaps the same hysteria that is fuelling the rise of right-wing populist ideas) that somehow nothing could be worse than now, that everything is simply terrible. But I feel that this moment is a moment of contestation, which is tough but at least means having arguments about the way the world should be, which seems better than the strange technocratic slumber of the past 25 years. Austerity has been horrifying and I realise that I’ve been relatively shielded from its effects, but the sight of the post-political elites being ejected from the stage of history is hopeful to me, and people seem to forget that the feeling of the rise of the right has been also met with a much broader audience for the left or more left-wing ideas than have been previously allowed to impact public discussion. That said, I do think we’re experiencing the dog-end of a long-term economic decline and this sense of emptying out is producing phantasms and horrors and creating a sense of palpable dread. I started to feel that the images I was making for ‘The Searchers’ engaged with this.

David Panos (b. 1971 in Athens, Greece) lives and works in London, UK. A selection of solo and group exhibitions include Pumphouse Gallery, Wandsworth, London, 2017 (solo); Sculpture on Screen. The Very Impress of the Object, Gulbenkian Museum, Lisbon, Portugal [Kirschner & Panos], 2017; Nemocentric, Charim Galerie, Vienna, 2016; Atlas [De Las Ruinas] De Europa, Centro Centro, Madrid, 2016; The Dark Pool, Albert Baronian, Brussels, (solo), 2015; The Dark Pool, Galeria Marta Cervera, Madrid, 2015; Whose Subject Am I?, Kunstverein Fur Die Rheinlande Und Westfalen, Düsseldorf, 2015; The Dark Pool, Hollybush Gardens, London, (solo), 2014; A Machine Needs Instructions as a Garden Needs Discipline, MARCO Vigo, 2014; Ultimate Substance, B3 Biennale des bewegten Blides, Nassauischer Kunstverein, Wiesbaden, (Kirschner & Panos solo), 2013; Ultimate Substance, CentrePasquArt, Biel, (Kirschner & Panos solo), 2013; Ultimate Substance, Extra City, Antwerp, (Kirschner & Panos solo), 2013; The Magic of the State, Lisson Gallery, London, 2013; HELL AS, Palais de Tokyo, Paris, 2013.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Left-Wing Antisemitism” Reconsidered

About two years ago I posted about how to spot “left-wing antisemitism.” I have now, after quite a lot of consideration, decided that my previous analysis was theoretically weak. So here is a reconsideration - in which I make an argument for adopting an account of populist and elitist antisemitism instead.

I dislike the phrase "left-wing antisemitism". Or at least the conjunction of "left-wing" and "antisemitism" comes too easily. Certainly one can identify the difference between a populist antisemitism and an elitist one: on the one side social theory that asserts the inherent unfreedom of society, due in most part a sort of conspiracy theory antisemitism that imagines the world, capital, and the media run by Jews keeping the rest of the population in check; on the other a social theory that asserts the inherent freedom of society, a commitment to the laissez-faire, which nonetheless is perpetually worried about the alien influence of Jews and the capacity of Jews to abuse their privileged status as Jews to undermine that freedom, whether by fomenting revolution or through undermining the principles of free and fair exchange. But the differentiation that we normally make between left-wing and right-wing does not so easily map on to populist and elitist antisemitism. Rather, the difference in bourgeois society between "right-wing" and "left-wing" centres essentially on the "Jewish question": that is, the question of how a Jew can live in a bourgeois society; what protections and privileges a supposedly universal society should afford Jews; whether the preservation and protection of the particularity of Jewry necessarily undermines the state's universal character. This is to say that the "Jewish question" (and this is where Marx's analysis is quite correct) occurs only in a society that is fundamentally unreconciled in regard to the relationship between universal and particular. To be either "left-wing" or "right-wing" as positions in bourgeois politics is to presuppose what is unreconciled: it is to push either for the universal or the particular while recognising the other.

That might sound a bit abstract but it can be fleshed out a little. Normally we talk about "right-wing" or "left-wing" as being an argument about whether we have a small or a big state. The right wing thinks that the state should make minimal incursions into people's lives, and thinks that freedom is best preserved where that freedom is asocial in character, where it asserts "freedom to stand against the state" as an element of precisely what the state is; while the left wing thinks that they state should be big in order to guarantee, for everyone, a certain type of social freedom: a "freedom in the state" in which the citizen must nonetheless participate fully. So the traditional right-wing position on the "Jewish Question" is to assert the Jew's right to practice Judaism in private, to be Jewish in private, so long as this private Jewishness does not threaten to overturn the state as such; while the left-wing position on the "Jewish Question" tends to assert that the Jew, just like everyone else, is free to do as everyone else is, but at the same time must at certain times give up his or her Jewish character in order to participate in that freedom: for the Jew to separate himself off from society is for him to condemn himself to a state of unfreedom, or to sanction state punishment for his a- or anti-sociality.