Text

How Traditional Publishing Works for Short Stories

You’ve written a short story and want it to reach readers, but you’re tired of combing through contests. Don’t worry—there’s a path to traditional publishing for short stories and you can follow it to build your writing resume with these steps.

1. Polish Your Work

Reviewing your story before submitting it is crucial. One or two typos may not disqualify you from getting accepted for publishing, but it could make the publisher pause.

Read through your work out loud to catch the tiny line edits that our eyes often skip over.

Ask a friend or family member to read it. A fresh pair of eyes on your work is priceless!

Use a text-to-speech reader to catch typos. You may hear the spelling errors more clearly, so try a site like this one: https://www.naturalreaders.com/online/

You can also use the spell check within your preferred writing software. It may not catch every spelling or tense-usage error, but it’s still helpful.

2. Research Publications

Longer manuscripts would normally look for publishing houses or imprints, but short stories just need publications.

Imagine the publishing world as an umbrella. Publishing houses are the fabric of the umbrella and imprints are the metal arms making the fabric extend. Imprints are subsections of publishing houses. Publications are like the stem and handle of an umbrella. They’re mostly independently owned, so that’s where you’ll find things like:

Literary magazines

Literary Journals

Ezines

Some are run by small groups of people who love making things like short-story anthologies and others will be professionally run magazines or journals with wide distribution. Your work may qualify for all of these publications depending on the length, topic, and what each publication is looking for.

3. Submit Your Work

Personally, I think finding the right places to submit your work is the most challenging part of publishing any story. There are an overwhelming number of places to consider. You might never learn about all of them!

Luckily, I’ve found a few tools to streamline the process.

Chill Subs is my current favorite site to find publications seeking short stories. You can find their site here: https://chillsubs.com/

This is what their homepage looks like—I’m breathing a sigh of relief just seeing it that encouraging welcome!

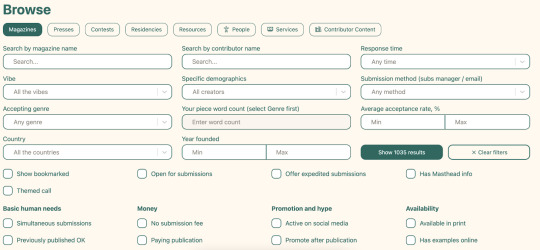

Once you make your free account (which is what allows you to track your submissions, results, etc.), you’ll find this page when you’re ready to start browsing:

It may seem like a lot, but selecting publication types and finding places that specifically want things like a spooky vibe or a quick response time makes submitting your work so much faster.

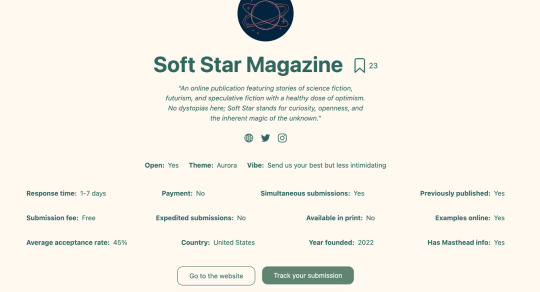

Just below this browsing section, you’ll find a list of publications if you just want to select a few without the filters. Here’s a screenshot of the first one I found:

There’s a great summary of the magazine and everything you need to know, like the facts that they have a super fast response time, don’t require a submission fee, and even their acceptance rate!

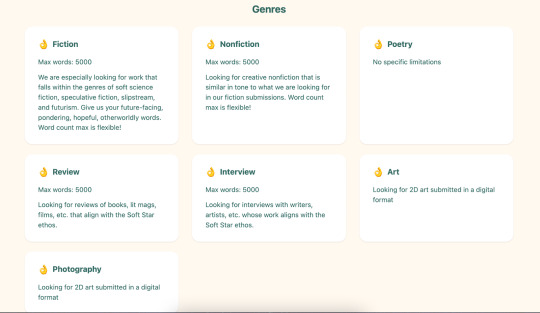

If you scroll further down under a publisher, you’ll find other invaluable information like:

Normally, you’d have to find all of these things by searching a publication’s website and recent published work. It would take much more time and you might not find what you’re looking for (I struggle when I’m too tired or distracted). Chill Subs will connect you to publications super quickly and easily, without charging a dime!

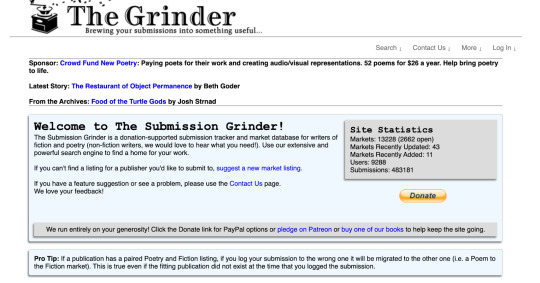

Next, I also like The Grinder, which you can find here: https://thegrinder.diabolicalplots.com/

Here’s what their homepage looks like:

This site is better for people who are more data driven! Right beneath the top of their homepage, you can automatically see the stats for The Grinder users who recently got accepted or rejected. At the time that I wrote this post, the people in the screenshot below had numerous rejections. I find it encouraging to see stuff like this because it’s a reminder that rejections happen to everyone. It’s just a matter of finding the right place for your work!

If you select “Search” on the top of the homepage, you’ll get a dropdown menu for things like searching for fiction or poetry submissions, plus publishers listed in alphabetical order.

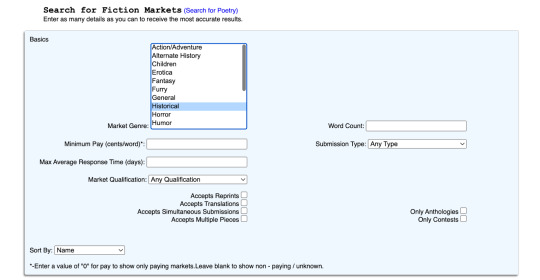

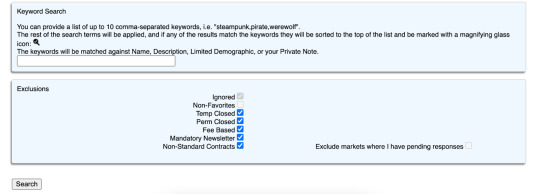

For the purpose of this post, I’ve selected “Historical” as my imaginary story I’d like to submit. There are many other genres in the box if you keep scrolling. Here’s what the start of this process looks like:

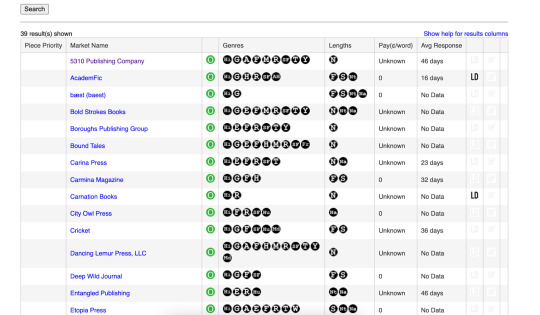

Hit “Search” and this comes up:

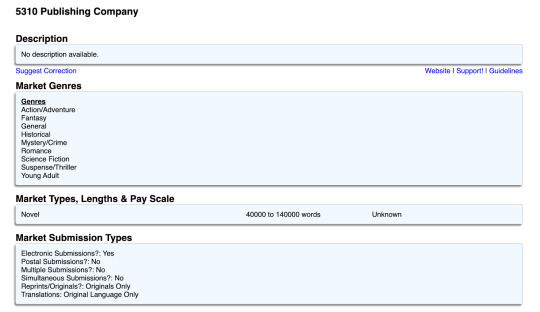

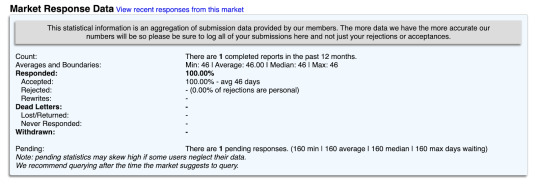

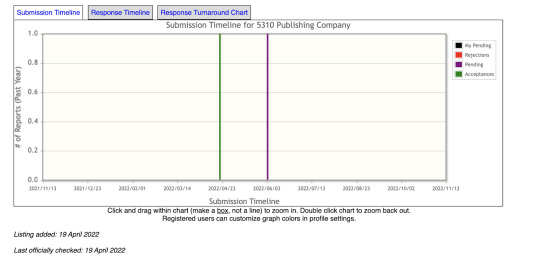

Right away you’ll see what each place pays, which genres and lengths they accept and their response time. I’ve clicked on the first publisher and found this data:

Enjoy using the charts and data to gauge where your stories should go! There are many publications working with The Grinder, so there’s tons to search through as you get a feel for what’s out there.

Other potential places to submit your work:

Submittable: https://manager.submittable.com/opportunities/discover (You’ll need to have submitted to a contest that uses Submittable to make an account, but the Discover tab has many publications organized by closest deadlines.)

Your university literary journals (if you’re a university student—most only accept work from students enrolled in that school, but it’s a major perk if you’re paying tuition because you won’t have to pay to send your work off!)

Local literary journals (many only accept work from writers who live nearby, which narrows down your competition).

4. Keep Track of Your Submissions

If you’re submitting more than one or two stories at a time, it’s best to keep a spreadsheet that tracks your submissions. As your writing career continues, you’ll always be able to reflect on which stories you submitted and where they went. It’s a great way to see how your writing has grown and note which publications you liked the most/had the most success with.

My submissions spreadsheet contains labeled columns for things like:

Date of submission

The story’s title

The page length/word count

The genre

The publication mae

The publication type

URL of publication if applicable

Final date of submissions

Date of notice if one is given

Potential prize money if applicable

Rejection or acceptance when notified

Some places only want unpublished writers, but most only want stories that haven't been previously published or placed in contest results. Keeping track of which stories receive prizes/publications makes it much easier to submit qualifying works in the future.

5. Evaluate Your Publishing Contract

Many publishers require writers to sign a contract so the legal reality of the transaction is clear to both parties. This happens for both short stories and long form work. You’ll have to review things like:

Allowing them to have print rights (typically worldwide because things are published online)

Allowing them to publish your picture and bio that is usually included in the submission form

Allowing them exclusivity (you may need to wait a specific time period before submitting the same story to other publishers/contests or selling it on your website)

Agreeing to author’s warranties (this means you agree that you wrote the story, it isn’t plagiarized, it isn’t libelous, and you don’t want it to be public domain)

Agreeing to a termination clause (the publisher typically reserves the right to terminate your publication contract for things like discovering plagiarism, getting sued for libel, if you sell the story to another publication within their exclusive time frame, etc.)

Agreeing to a reversion of rights clause (you’ll get all of the above rights to sell/submit the story if the publisher doesn’t get your story published by the deadline included in your contract)

Agreeing to payment terms (if you’ll be paid based on how many magazine copies are sold, based on your word/page count, or if you’ll get a flat fee). Also, how you’ll get paid (in installments, within a time frame after publication, via direct deposit or check).

A big thing to note—if a publisher doesn’t include a reversion of rights clause, they essentially want to lock your story within their publishing company permanently. You’ll never get the rights back for submitting or publishing it elsewhere. That includes if you write a collection of short stories and want to publish an anthology—you wouldn’t get to include the story taken by the original publisher.

It’s very important to know your rights as a writer before submitting.

You can read more about contract details over at Writing Cooperative.

And you can always look through Writer Beware, which tracks scams and legitimate publication opportunities.

-----

Hopefully this helps you get started with your next venture in getting published! The process doesn’t have to feel as confusing as it often does. Best of luck! 💛

299 notes

·

View notes

Text

Conflict: Method and Meaning

When I write stories, and I'm not emotionally decompressing something awful, and I'm not satisfying some sadism through breaking fictional characters' hearts and minds, then it's odd to hear that conflict is the central feature of every story.

There should be another word for it, but because there isn't I want to expand the definition of the term conflict in this context. Story conflict can be a curiosity about a world that the central character or the reader doesn't know. It can be everything or something about that world that the central character doesn't know, even if they're not curious. There can be a conflict that gets that character started with living through the story, but by the end the only resolution is character development from a state that previously wasn't the obvious problem in the first place. There can be the conflicts between two equally true and valid tenets that cannot coexist, but, here they are in the same story, ready to crash into each other. There can be the more classical conflicts: exile, betrayal, rebellion, disaster, bereavement, and so on.

One distinction I heard and liked is that if the central character is a shining-armoured knight errant from a fairy tale, then the external conflicts can be dragons while a character's internal conflicts are knightly ordeals or vigils (but the former I have only read in Tamora Pierce's Lioness Quartet, and the latter in George R.R. Martin's A Song of Ice and Fire.)

The dragons are what happens in the story, or the plot conflict.

The ordeal, or the vigil, is why the story has any meaning.

That's a rudimentary understanding of story conflict. It is something that I've found helpful, and can go through the motions of constructing a complete story around the resolution to the central conflict.

Beyond that rudimentary, though, I tend to think in two contradictory bits of advice. The first is to develop the story around a strong central theme, to have a clear idea of what you want to say with this story. The second is not to do that, because a heavyhanded message removes the nuances and complexities that give a story momentum and pizzazz. If you truly do have a drive towards the theme that you're planning then that's going to make its way in there even if you don't plan it. It's going to barge in at every opportunity and seep between the cracks in the walls.

When it comes to troubleshooting writer's block or a dry spell in creativity, any of these might work.

I might start out excited by what I simply think is a nifty story idea, like "What if a haemophiliac royal prince was turned into a vampire?" or, "What if the myth of Galatea ended as tragically as the myth of Tithonus?" and deep personal issues start to show between the lines.

I have to believe those are the themes and conflicts that make a story work. As Ernest Hemingway said of writing, there's nothing to it, "All you do is sit down at a typewriter and bleed."

0 notes

Text

(excerpts from Story Structure 102 by Dan Harmon)

The Rhythm Of Psychology

Your mind is a home, with an upstairs and a downstairs.

Upstairs, in your consciousness, things are well-lit and regularly swept. Friends visit. Scrabble is played, hot cocoa is brewing. It is a pleasant, familiar place.

Downstairs, it is older, darker and much, much freakier. We call this basement the unconscious mind.

The unconscious is exactly what it sounds like: It's the stuff you don't, won't and/or can't think about. According to Freud, there are dirty pictures of your mother down there. According to Jung, there are pipes, wires, even tunnels down there that connect your home to others. And even though it contains life-sustaining energies (like the fuse box and water heater), it's a primitive, stinky, scary place and it's no wonder that, given the choice, we don't hang out down there.

However, your pleasure, your sanity and even your life depend on occasional round trips. You've got to change the fuses, grab the Christmas ornaments, clean the litter box. To the extent that we keep the basement door sealed, the entire home becomes unstable. The creatures downstairs get louder and the guy upstairs (your ego) tries to cover the noise with neurotic behavior. For some, eventually, the basement door can come right off its hinges and the slimy, primal denizens of the deep can become Scrabble partners. You might call this a nervous breakdown or psychotic break, it doesn't matter. The point is: Occasional ventures by the ego into the unconscious, through therapy, meditation, confession, sex, violence, or a good story, keep the consciousness in working order.

This is the rhythm of psychology: Conscious-unconscious-conscious-unconscious-etc.

The Rhythm Of Society

Societies are basically macrocosms (big versions) of people, only instead of "consciousness," a society's upstairs is "order," and its basement is "chaos."

Whereas the health of an individual depends on the ego's regular descent and return to and from the unconscious, a society's longevity depends on actual people journeying into the unknown and returning with ideas.

In their most dramatic, revolutionary form, these people are called heroes, but every day, society is replenished by millions of people diving into darkness and emerging with something new (or forgotten): scientists, painters, teachers, dancers, actors, priests, athletes, architects and most importantly, me, Dan Harmon.

Societies are macrocosms of people in another way: Eventually, they die. There is competition between different societies. The losers are eaten and the winners reproduce.

Like people, societies become neurotic and can eventually break down when they make the mistake of thinking the downstairs shouldn't exist. America is a terrific example of this, as our fear of the unknown continues to create more unknowns and more fear. It's now punishable by bombing to have a problem with America's bombing policy. In a human being, the equivalent would be diagnosable as symptomatic. Our basement is brimming with creepy crawlies, the pressure on the door is building. There has never been a bigger need for heroes and they have never been in such scarcity.

One of two things is going to happen. Someone's going to open that door and go down there, or that door is going fly off its hinges. Either way, social evolution will not be cheated of its rhythm and it's going to get sloppy. We all know it. We all walk around with that instinctive understanding in our unconscious minds.

The rhythm of society: Order-chaos-order-chaos-etc.

0 notes

Text

DPS-Inspired Extemporaneous Thoughts: Return to Instinct

An English class in high school taught me the following advice: don't use adjectives, adverbs, or verb forms of 'to be' in your writing.

I figured out why later on. Overall, it was good advice. 'Walked slowly' could be worded with more efficiency by writing 'ambled' instead, or by keeping the verb and deleting the adverb. That same image could be described more creatively by comparing the pace of the character to a glacier. To follow this advice turned abstract and vague information into clear, vivid, specific imagery. It lent me valuable skills.

I don't always follow that advice. It's not some religious edict. I can't stop thinking in lengthy compound sentences.

The standards set by that advice are good and useful.

A pitfall that I noticed, though, is coming to value the rules over substance.

That's what I find freedom from, at the part of the movie when John Keating tells his students to rip the page out of their textbooks that maps every poem on a coordinate plane. Instead of repeating the opinions and arguments made within those parameters—an example, I'm thinking, is "the ballad of Tam Lin is imperfect in form as the nature of a ballad, but has immense cultural significance as a counterpoint to distressed damsels of many other fairy tales"—the course focuses on reminding the students that they're allowed to dislike a poem at all, or to like a poem, and who knows they could even wonder why and maybe the answer will sometimes be that the perfection of form is catchy.

There should be as many reasons for each students' like of a poem as there are students, or even the same student caught at different moments.

Analysis of form or of the poem's interaction with society are steps two through twelve.

When step one, exploring the personal response and what that says about one as a person, when that gets left out, then I'm likely to think that the rest has no foundation.

Do you know yourself enough to check your own motives?

Can you consider the situation clearly?

Is this analysis or criticism in good faith?

If the answer is no to any of the above, then there's nowhere constructive to take a discussion about an artistic work.

0 notes

Text

DPS-Inspired Extemporaneous Thoughts: John Keating was Collateral Damage

Writing prompts don't usually work for me, especially for fanfiction of source material that I'm not over the moon about. It just so happened this month that I caught a story idea from...a prompt for a fandom that I'm not over the moon about. Guess what, I'm going for it.

But I wondered why I'm not more into the source material. I like being familiar enough with the Dead Poets Society movie that I can sit through a whole video essay about why it's the best example for how to construct queer readings. I can understand the New-England-boarding-school-prepster aesthetic appeal. It has its moments that support a thematic argument, like the quirky teacher's "art is what makes life worth living" speech, and the students breaking curfew to sit in the cave and read poems and make a world for themselves, or the students standing on top of the tables at the end.

When I first watched it, though, and even now, the stories of the students and the teacher seemed very disconnected from each other. There was something underdone about it, some lack of momentum, so I got the sense that it didn't come close to fulfilling its dramatic potential.

But maybe I didn't know that I was expecting something else, and I can't even point to something else to say what I was expecting. The screenwriter, Tom Schulman, spoke in 2013 at the University of California in Santa Barbara about how he based the characters of Knox Overstreet and Neil Perry on people that he grew up with. The script itself was his own spec-work, and he'd had to defend it against changes that were supposed to make the story more marketable. All that considered, along with how many people do hold it near and dear, the loosely-affiliated subplots and slice-of-life level of plot tension could be features rather than flaws.

Since I'm not a boarding school boy from 1959 Vermont, I can't say that what makes it great is its realism, but from my own pessimism I do think that's a highlight. If I could hone in on the most main of main characters, there would be three: Mister Keating, who introduces the main thematic conflict; Neil Perry, whose character development makes the plot happen; and Todd Anderson, who gets caught up in a plot that makes his character development happen. Charlie "Nuwanda" Dalton, Meeks, Pittsie, Knox and Cameron all add something crucial to the story, but I say the main thread is spun from three characters.

And they don't overcome the odds. As I wrote for the title of this entry, Keating introduced powerful ideas but even a direct suggestion (for Neil to speak honestly with his father) is outright rejected and spirals completely out of Keatings' hands. Neil is as self-possessed as an emotionally abused son can be, up until the very end, but he burns bright and burns out and does not prevail against the social pressures in his life. Todd loses two people that changed his life for the better, and the only consolation is that not even the loss of them can undo their changes. It's dreadfully unsatisfying, but that is what I find the movie captures best. I can appreciate it for being a Memento Mori of original thought. Even if all these students are from wealthy enough families that they can attend an exclusive boarding school, for all the privileges they have in this environment and the world, if they don't conform because they'd rather be human or something then they are going to lose. It shouldn't be that way, but I wouldn't like the movie as much as I do if it were completely aspirational and escapist. If even these skinny white boys from wealthy families can't be people—explorers, artists, true friends, (and, on occasion if not by default, sixteen-or-seventeen-year-old purveyors of cringe problematicism c.1989) or literally alive—because of the extremely repressive society that they're in...Then what does that forebode for the rest of us? How have we been doing since 1989, or 1959 for that matter?

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Does Researching/Writing Historical Fiction Count as Historybounding?

I hated history at school because it was so abstract: "date of event, name of important historical person, learn by rote". History is much more interesting to me when it's about the material culture at the time: culinary history, architecture, clothing, technology, aesthetic sense, and so on. I take that lens to settings such as Ancient Mesopotamia, Minoan Crete, Heian-era Japan, Prohibition-Era United States...a few others in between, and then I usually lose interest after the 1920s. Wake me up when the 80s ends.

0 notes

Text

Narrative Psychology

Bruno Bettelheim has become a notorious figure. He was the worst combination of misguided and authoritative at the time (1967) that he was publishing his writings about autism. Different sources that I have looked up cannot seem to decide if Bettelheim had truly suffered in and survived a concentration camp as he claimed. Finally, his writings about the psychological value of fairy tales are allegedly plagiarized by him from Julius E. Heuscher's "A Psychiatric Study of Fairy Tales" (1963 publication, revised in 1974).

It remains the following case, whether it was originally Heuscher's or Bettelheim's, that my mind keeps going back to whenever I endeavor to analyze fiction media—because it still rings so true to me:

In Rapunzel we learn that the enchantress locked Rapunzel into the tower when she reached the age of twelve. Thus, hers is likewise the story of a pubertal girl, and of a jealous mother who tries to prevent her from gaining independence—a typical adolescent problem which finds a happy solution when Rapunzel becomes reunited with her prince. But one five-year-old boy gained quite a different reassurance from this story. When he learned from his grandmother, who took care of him most of the day, would have to go to the hospital because of serious illness—his mother was working all day, and there was no father in the home—he asked to be read the story of Rapunzel.

At this critical time in his life, two elements of the tale were important to him. First, there was the security from all dangers in which the substitute mother kept the child, an idea which greatly appealed to him at that moment. So what normally as a representation of negative, selfish behavior was capable of having a most reassuring meaning under specific circumstances. And even more important to the boy was another central motif of the story: that Rapunzel found the means of escaping her predicament in her own body—the tresses upon which the prince climbed up to her room in the tower. That one's body can provide a lifeline reassured him that, if necessary, he would similarly find in his own body the source of his security. This shows that a fairy tale—because it addresses itself in the most imaginative form to essential human problems, and does so in an indirect way—can have much to offer to a little boy even if the story's heroine is an adolescent girl. These examples may help to counteract any impression made by my concentration here on a story's main motifs, and demonstrate that fairy tales have great psychological meaning for children of all ages (...) irrespective of the age [and gender] of the story's hero.

As a layperson only qualified by liking to read and write fiction, I like analyzing fiction. I like to pinpoint and map its forms, the techniques made use of within the medium, the intention of the author or collaborators, and observe how that meaning changes in the context of different audiences.

What I find does get lost in all that analysis, though, is each person's relationship to the work having a more complicated and interesting reason for it—that cannot reliably be judged on sight by what someone has a fiction-media interaction with. It's not even automatically my business, and of course I'm going to judge harmful patterns of behavior harshly—but I find a collective forgetting of a crucial idea: to approach with curiosity a difference in interpretation of a fictional work is sometimes worth a try.

Now let's make a drinking game of future posts getting hashtagged with "this is not one of those worthwhile times, holy helicon what a bad take" and "i am telling on you to my therapist".

0 notes