Text

Using hip hop to battle South Sudanese marginalisation in Melbourne

Hip hop has come out of Black communities in North America, from around the late 1970s. The genre was an underground counter-culture movement, which addressed issues such as racism, police violence, drug use and poverty. Hip hop was largely inaccessible for middle class White Americans, in that it employed the use of Black vernacular English, the musical style itself was new and radical, and the venues in which it was played were mostly Black. As the movement grew and gained support from outside the African-American community a decade later, hip hop remained a Black dominated art form, and many Black hip hop artists have been able to put their messages about marginalisation and oppression of the Black communities in America out into the public in a big way. This publicity has contributed to public awareness of inequality and the mutual appreciation of the genre has contributed to breaking down race barriers in the US. Hip hop music has created accessible avenues for marginalised and disadvantaged Black youth, especially from the ghettoes of North America, to pursue artistic careers in a racist society which excluded or exploited Black artists. The success of hip hop music in the maintenance of Black artists’ ownership of their own music in such an environment is partially due to it’s counter-culture origins. Hip hop began outside of the acceptable conventions of music according to the (White dominated) Western music industry.

Marginalisation of Black communities and devaluation of Blackness is also a huge issue in contemporary Australia. With Australia’s history of attempted Aboriginal genocide which extends into the present day indirectly through the unjustifiably large number of Black deaths in custody[1] which are only increasing, to the disparity in health conditions and living standards for Aboriginal Australians and Non-Aboriginal Australians. Media representations of Blackness provide a surface level representation of the ways in which Blackness is devalued in Australia. South Sudanese are portrayed in Australian media as outsiders, violent and unwilling to adapt to Australian society[2]. There are four main representations of South Sudanese-Australian people in Australian Media: as refugees; (male) perpetrators of violence; (female) victims of violence; and as “recipients of Australia’s generosity”[3]. All of these identities are constructed as alien to Australia. Large numbers of media reports conflate South Sudanese people with violence, suggesting that South Sudanese have an intrinsic violent nature[4]. In addition, media representing ‘Sudanese violence’ reports included instances and footage of violence committed by people from backgrounds other than Sudanese, as well as reporting of Sudanese ‘gang violence’ in cases where South Sudanese are the victims of violence perpetrated by other races including White people[5][6]. This demonstrates that these media representations are inaccurate constructions. Further, these representations are used as justification for discriminatory policy such as the 40% cut in the numbers of African asylum seekers accepted by Australia. The Minister for Immigration stated that this cut was because African asylum seekers “don’t seem to be settling and adjusting into the Australian life as quickly as we would hope”[7]. Beyond negative constructions of Blackness, there is an absence of South Sudanese Australians portrayed in any type of every-day, normal, or positive representations[8]. Alex Hargreaves calls these portrayals, such as soap operas and game shows, ‘genres of conviviality’[9], and people from non-English-speaking backgrounds are not portrayed in soap operas as normal, every-day people[10]. This adds to the construction of Sudanese Australian’s as strangers, different, and not regular Australians[11].

In a Dialogue Theatre performance (an explanation of Dialogue Theatre process can be found here) by 5 members of the Melbourne South Sudanese community in March 2017 at Metrowest, Footscray, a few key concerns of the community were discussed. The actors generated the content of the performance through discussion and workshops with each other, and attempted to capture different viewpoints within their community to present a holistic view of different concerns. The actors conveyed concerns about the negative representation of South Sudanese in Australia as intrinsically violent and unwilling to contribute to Australian society. The actors represented the ripple effects of police violence and targeting of young South Sudanese in Melbourne, which has been documented in the literature[12]. They represented in their performance the frequency of beatings their children experienced at the hands of the police, to the extent where children had normalized this occurrence and did not want to ‘make a big deal’ of it. The actors also represented the contradiction of the Australian legal system felt by some parents, which threatens to remove their children if they employ physical discipline, yet ‘law enforcers’ such as the police, regularly physically assault their children[13]. Furthermore, policy makers and media have attributed alleged South Sudanese violence and supposed South Sudanese law-breaking to the inability of South Sudanese parents to effectively discipline their children[14]. The significant difference in Australian and South Sudanese family legal systems and practices means that South Sudanese parents can find themselves unable to implement parenting techniques which do not conflict with Australian law[15]. While some South Sudanese parents have altered their parenting styles to accommodate for the new host culture and legal practices with significant success[16]. However, this approach exacerbates one of the other central concerns represented by parents in the Dialogue Theatre performance: the fear that children will lose their South Sudanese culture, and the need to preserve and practice their culture to prevent this.

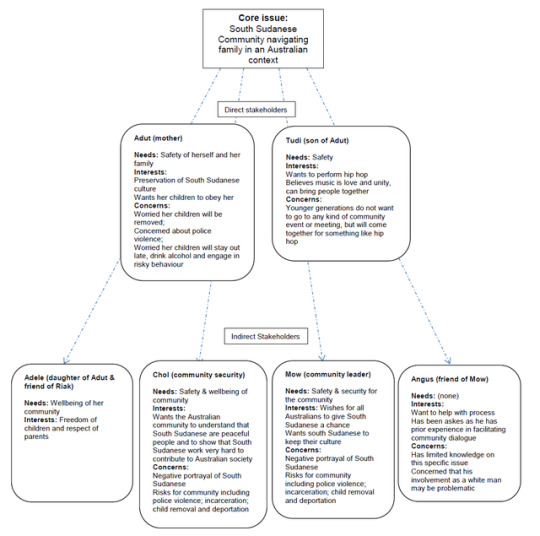

This tension was partially represented by the central conflict of the performance. (A conflict map representing the key concerns of each character can be found here). A young rapper requests to perform at a community fundraiser event. However, his request is rejected by older generations who condemn hip hop as a bad influence, and instead want the fundraiser to only involve traditional Dinka music and dance. When he and his friend conspire to perform hip hop regardless, a public conflict breaks out. However, hip hop music and programs have the potential to address many of the issues highlighted by these actors, including concerns of cultural corruption.

A potential solution to the structural problem of negative media representations is the development of community hip hop programs in the Melbourne South Sudanese community. For the characters Chol and Mow, a central concern was promoting a positive image of South Sudanese communities and spreading accurate information. Hip hop programs facilitate communication between migrant and host cultures across language barriers as well as communication barriers as a result of trauma[17]. While many messages conveyed in mainstream American hip hop involve drug use, hyper-sexualised video clips and law-breaking, contemporary South Sudanese Melbourne rappers are trailblazing their own genres of hip hop which promote positive representations of their communities[18], such as Melbourne’s Ur Boy Bangs. If supported by the community and provided with sufficient resources, a hip hop community could mobilize young South Sudanese to promote positive representations of their communities. One such example is the organisation Desert Pea Media, who have produced many indigenous hip hop videos from remote areas in order to “create important social and cultural dialogue”[19]. Another example of the ways in which music and arts programs can assist in countering the negative portrayal of South Sudanese in mainstream media is the project Good Starts Arts. This project provided young Sudanese Australian women an opportunity to rewrite inaccurate, racist reporting on the murder of, Liep Gony[20]. The project provided complexity to the reductive construction of Sudanese Australians by the mainstream media[21].

Hip hop music provide positive Western representations of Blackness for young South Sudanese within a new alienating culture[22]. In Awad Ibrahim’s article titled ‘Becoming Black: Rap and Hip-Hop, Race, Gender, Identity, and the Politics of ESL Learning’, he discusses the way in which Black migrants from mostly Black countries to countries where Whiteness is common and normalized, are suddenly placed in a context where they are primarily viewed as ‘Black’, and “the antecedent signifiers become secondary”[23]. They “enter a social imaginary … in which they are already constructed, imagined and positioned and thus are treated by the hegemonic discourses and dominant groups, respectively, as Blacks”[24]. In the face of negative or absent representations of South Sudanese and in Western media, positive representations of Blackness are extremely important[25]. Some of the strongest positive Western representations of blackness can be found in rap and hip-hop[26].

Hip hop programs assist young South Sudanese in the acculturation process[27]. For young people who have experienced trauma and war, it can be much harder to integrate into a new society for a number of reasons, but “both the literature and Sudanese refugees themselves highlight refugee recovery as primarily a social process”[28]. Creative music projects and music programs have been shown to greatly assist social integration, building social networks and re-creating social identities[29] [30]. DIY (do-it-yourself) hip-hop is one way for young (ex)refugees to create opportunities, produce and construct meaningful identities and to promote and spread positive messages to other African (ex)refugee youth[31]. Creating visible identities which other South Sudanese and African (ex)refugee youth will be able to recognise and identify reduces their risk of isolation and builds social networks to bridge the severe lack of support networks for young African refugees arriving in Australia[32].

The development of hip hop communities are excellent ways to mobilize young South Sudanese (ex)refugees. In the South Sudanese Dialogue Theatre performance, the character Tudi expressed concerns that young South Sudanese do not want to come to community meetings or events, thus reducing their participation and involvement in South Sudanese culture. This is a major issue identified by the character Adut, who wants South Sudanese children to learn about and participate South Sudanese culture. While Tudi expresses that he does not want to sing in Dinka, this does not prevent hip hop programs being run in conjunction with older generations who can provide cultural content. There is also potential for strengthening of inter-generational relationships with reciprocal resource sharing in this way. Ibrahim discusses the benefits of hip hop on ESL learning, and one of the issues identified within the Dialogue Theatre was the increasing language barrier between parents and children.

Hip hop programs run by South Sudanese and African (ex)refugees should receive more funding in Victoria due to the proven outcomes. The success of the Dialogue Theatre format in generating dialogue and strengthening relationships between younger and older generations of South Sudanese in Melbourne has demonstrated some of the benefits of collaborative arts programs for combatting some of the adversity the South Sudanese community faces in Melbourne. Furthermore, funding and support should be provided for South Sudanese hip hop performances, including addressing the gap in high quality musical criticism for South Sudanese hip hop.

[1] Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody1998, Council for Aboriginal Reconciliation

[2] Nunn, C 2010, ‘Spaces to Speak: Challenging Representations of Sudanese Australians’, Journal of Intercultural Studies, vol. 31, no. 2, pp. 183-198.

[3] Nunn, et. al., p.186

[4] Nunn, et. al.

[5] Nunn, et. al.

[6] Windle, J 2008, ‘The racialisation of African youth in Australia’, Social Identities, vol. 14, no. 5, pp. 553-366

[7] Andrews 2007 cited in Windle et. al., p.553

[8] Nunn, et. al.

[9] Nunn, et. al., p.184

[10] Nunn, et. al.

[11] Nunn, et. al.

[12] Windle, et. al.

[13] Levi, M 2014, ‘Mothering in transition: The experiences of Sudanese refugee women raising teenagers in Australia’, Transcultural Psychiatry, Vol. 51, no. 4, pp. 479-498.

[14] Levi, et. al.

[15] Juuk, B 2013, ‘South Sudanese Dinka customary law in comparison with Australian family law’, ARAS, vol. 34, no. 2, pp. 99-112.

[16] Levi, et. al.

[17] Marsh, K 2012, ‘The beat will make you courage: The role of a secondary school music program in supporting young refugees and newly arrived immigrants in Australia’, Research studies in Music Education, vol. 34, no. 2, pp. 93-11

[18] McCulloch, S 2013, ‘Portrait of Riak’, un Magazine, vol. 7, no. 2, viewed 21 April 2017, http://cargocollective.com/scottmcculloch/Portrait-of-Riak

[19] Finlayson, T 2017, ‘About Desert Pea Media’, Desert Pea Media, viewed 21 April 2017, http://www.desertpeamedia.com/desert-pea-media/

[20] Nunn, et. al.

[21] Nunn, et. al.

[22] Ibrahim, AEKM 1999, ‘Becoming black: Rap and hip-hop, race, gender, identity and the politics of ESL learning’, TESOL Quarterly, vol. 22, no. 3, pp. 349-369.

[23] Ibrahim, et. al.

[24] Ibrahim, et. al.

[25] Ibrahim, et. al.

[26] Ibrahim, et. al.

[27] Marsh, et. al.

[28] Westoby, P 2008, ‘Developing a community development approach through engaging resettling Southern Sudanese refugees within Australia’, Community Development Journal, vol. 43, no. 4, p. 486.

[29] Ibrahim, et. al.

[30] Marsh, et. al.

[31] Wilson, M J 2011, ‘Making space, pushing time: A Sudanese hip-hop group and their wardrobe-recording studio’, International Journal of Cultural Studies, vol. 15, no. 1, pp. 47-64.

[32] Wilson, et. al.

0 notes

Video

youtube

Riak (Melbourne) - What’s My Name

Melbourne based rapper Riak played the character Tudi (also a rapper) in the South Sudan United Dialogue Theatre piece performed on March 26th at Metrowest, Footscray.

0 notes

Text

‘The accident of art and Ur Boy Bangs’

William Stanforth provides a rare piece of genuine critical review on Melbourne rapper Ur Boy Bangs (Bangs) in overland magazine: ‘The accident of art and Ur Boy Bangs’.

“The track is confusing from an artistic standpoint, as it parodies US gangsta rap culture while looking like a serious attempt at creating rap music. ‘Take U to Da Movies’ upholds the egocentric rap aesthetic, yet the subject (Ur Boy taking a girl to the movies, paying for the popcorn and so on) is endearing and oddly polite.”

The lyricism along with the absurdity of the video (Bangs performs in front of green-screened JPEG images of city skylines, expensive cars, Australian cash and so on) could be the reason for its traction online.”

“Like many other viral videos, the success of ‘Take U to Da Movies’ had an accidental element. Deng explained, ‘It was an experiment; I wanted to work out how green screen [also known as chroma key compositing, a post-production filmmaking technique] worked, and Bangs had the idea for the images. I didn’t know anything about YouTube.’ Deng felt the popularity of ‘Take U to Da Movies’ was due to its simplicity. ‘There is no technology where I come from and I wanted to do something simple, something people could relate to. Some people find it funny and some just try to work out how we did it.’”

“The truth is that it doesn’t matter if you think ‘Take U to Da Movies’ is a good example of rap music or not. It doesn’t matter if it was intended as a parody or if it was meant to be serious (or somehow both). There is no longer a point in discerning the intention of a creator in the post-postmodern world. What is important is working out why one music video speaks to a global audience and countless others fall through the cracks. It is not arbitrary. My guess is that what Ajak Chol and Ez Eldin Deng are doing resonated because it represents a new honesty in art, a realness that’s far from the egotistical laughter of a talk show host that modern culture is likely to leave behind.”

0 notes

Video

youtube

This is one of Bangs’ first hits - Take you to the movies (2009).

Despite the fact that most of Bangs’ critics assume he is not self-aware of his art (see youtube comments and internet discussions as well as patronising media reporting around the Jimmy Fallon/Bangs incident), Bangs often writes lyrics which are intentionally in contrast to common subject matter for popular American rap. He says “I’m just trying to stick with what I started with. Trying to be nice, trying to be respectful. People write about cars, necklaces and money, how they’ve got more girls and I’m like, "okay, anything else? Anything new you could write about?" No one ever thought of writing a song about taking a girl to the movies.”

However, there are a few pieces of genuine critical review. Scott McCulloch’s ‘Portrait of Riak’ for unMagazine in 2013, and William Stanforth’s ‘The accident of art and Ur Boy Bangs’ for Overland in 2015 provide some starting points for critique, however both articles are written by white men. High quality critique from South Sudanese, (ex)refugees and migrant diaspora is needed to gain a deeper understanding of this genre.

This song gained lots of media and public attention when it was played on a famous talk show in the US - the Jimmy Fallon show - on the ‘do not play’ segment. During the show, bangs was ridiculed for his lyrics and style. Bangs repsonded with a cover of his own song ‘Take you to the movies’, with new lyrics direced at Fallon: ‘Do not watch’

0 notes

Text

South Sudan United

A South Sudanese Dialogue Theatre performance on the 19th and 24th of March at Victoria University and West Space respectively represented some of the key concerns of the Melbourne South Sudanese community. 5 South Sudanese actors wrote, workshopped and performed their work in conjunction with an experienced Dialogue Theatre practicioner. See the event description here. The central conflict revolves around younger and older generations of South Sudanese Australians who were not born in Australia, represented by the characters of Adut (the mother), and Tudi (her son). While Tudi wants to perform hip hop at the community fundraiser, his mother Adut wants him to participate only in Dinka music and dance. When he and his friend conspire to perform hip hop at the fundraiser anyway, a public conflict breaks out. However the performance involves many other issues facing the South Sudanese community in Melbourne, such as police violence, tensions between cultures and laws, and racism.

0 notes

Photo

Conflict map of South Sudan United Dialogue Theatre performance

0 notes

Text

Portrait of Riak

Scott McCulloch critiques the music of Riak and diaspora rap, hip hop and poetry in his article, ‘Portrait of Riak’. MucCulloch says of rapper Riak and other South Sudanese diaspora hip hop artists that they are “dispelling their experiences as urban refugees and migrants”, and “Most of these outfits adhere to an unabashedly DIY ethos — all writing, playing, recording and making their videos themselves — which in turn has created an enigmatic genre of experimental Diasporic rap”

“Helplessly scattered and broken both on the page and when performed, Riak’s flow sits outside most rap styles — including those of his contemporaries. This leaves him in a tenuous and perplexing position: on the periphery of a peripheral culture.”

McCulloch compares Riak’s style and (for many) inaccessibility to earlier rap movements: “Atmosphere and feeling are in the blood of this music. It is not without antecedents: in 1994, Triple 6 Mafia self-released the cassette, Smoked Out Loced Out. A dazzling evocation of blackness, the album utilises avant-garde techniques of repetition and analogue tape-loops”.

This cassett came out of “the first African-American neighbourhood in the United States to be constructed and controlled by African-Americans ... While stylistically very different, Riak and his community are doing a similar thing”

0 notes

Text

Becoming Black

Ibrahim discusses the process of becoming Black during the migration process from mostly Black countries such as African countries to mostly or White-centric countries such as Canada and the US.

Ibrahim notes that while previously his identity was defined by others as based on interests and attributes unrelated to a specific idea of ‘blackness’. But in the process of migrating to a predominately white country, young Africans for instance are forced into a constructed identity as ‘Black’, and “the antecedent signifiers become secondary to … Blackness” (Ibrahim, 199, p.354). African immigrants and refugees to predominantly white countries such as the US, Canada and Australia “enter a social imaginary … in which they are already constructed, imagined and positioned and thus are treated by the hegemonic discourses and dominant groups, respectively, as Blacks” (Ibrahim, 1999, p.351). Fanon (1967 in Ibrahim, 1999, p.353) discusses the way in which black individuals are “overdetermined from without”. The type of predetermined representation is defined by overwhelmingly white media and politicians, while black voices and black definitions of black identities are glaringly absent (Nunn, 2010). The Commonwealth Office of Multicultural Affairs found that the Australian media does not represent the diversity of Australia (Nunn, 2010). There is an absence of South Sudanese Australians portrayed in any type of every-day, normal, or positive representations (Nunn, 2010). Alex Hargreaves calls these portrayals, such as soap operas and game shows, ‘genres of conviviality’ (Nunn, 2010, p.184), and people from non-English-speaking backgrounds are not portrayed in soap operas as normal, every-day people (Nunn, 2010). This adds to the construction of Sudanese Australian’s as strangers, different, and not regular Australians (Nunn, 2010). Forced to identify with ‘blackness’ in the context of being ‘other’ due to their non-whiteness, young African immigrants look to positive representations of blackness (Ibrahim, 1999). Some of the strongest positive representations of blackness, constructed by black people themselves, can be found in rap and hip-hop (Ibrahim, 1999).

0 notes