#Far Humbler Halls {England}

Text

Tag Drop; Lucy Pevensie

#Gay & Golden Haired {Fc}#Big & Brave {Peter}#Tender Hearted {Susan}#Tempting Fate {Edmund}#Pillar Of Strength {Mum}#Courageous Heart {Dad}#Swift To Spring {Friends Of Narnia}#Knows Her People Safe {Narnians}#Dwells Beyond The Stars {Aslan}#Far Humbler Halls {England}#In Truth I Am The Least {Headcanons}#Circlet Of Bright Gold {Clothes}#Return My Care With Love {Narnia}#Thinks Twice & Thrice & Yet Again {Quotes}#Heavy On The Heart {Music}#Light Upon The Head {Likes}#Tears Wept In Silence {Wishlist}#The Faithful {Muse; Lucy Pevensie}#V; Pale Morning Sings#V; Been Blindly Deceived#V; Guess What’s Coming Next#V; Shifts One Way Or The Other#V; A Children’s Tale#V; Old Old Winds Blowing Back Round#V; Lead You Back To Me#V; Sing A Song For You#V; Night Explodes In Laughter#V; Way Your World Can Alter

1 note

·

View note

Text

History of Suffolk county’s architecture

The architecture of the county of Suffolk is a mix of colour and character, with timber-frame and flint, pargetting and thatched roofs, moats and chimney stacks

By Jenny Woolf

Scattered around the flinty-grey churches of Suffolk, you will sometimes see groups of brightly-coloured cottages, for all the world like flowers growing about the stumps of dark oaks. This contrast is typical of Suffolk, for this Eastern county has no quarries or brickworks, and its people have always collected bits and pieces with which to create their buildings. As a result, many Suffolk buildings are glorious jumble of flints from the beaches, rushes from the marshland, and clay and timber from the farms.

That is not to say that Suffolk lacks grand homes. There is Elveden Hall, where Angelina Jolie filmed part of Lara Croft: Tomb Raider, not to mention Framlingham Castle and Ickworth House. Yet somehow it is often the humbler homes that engage the emotions and delight the eye.

Just inside Suffolk’s southern border, Long Melford’s rambling village street is lined higgledy-piggledy with five centuries’ worth of typical vernacular houses. Some are plastered, some are timbered, and some boast the enormously tall chimney-stacks that betray their Tudor origin.

Five hundred years ago, those quaint buildings represented the last word in homes and warehouses for hard-nosed modern businessmen, for medieval Long Melford was a thrusting, busy place. Like many other Suffolk towns – notably beautiful Lavenham – it was built with money from the cloth trade, and it did very well indeed. In Lavenham, the beautiful timber-frame Guildhall of the Wool Guild of Corpus Christi still stands in the market place and is now under the care of the National Trust, with a museum and exhibitions on the medieval cloth industry.

There were around 30 weaving businesses in Melford, plus associated craftsmen like dyers who made pigments from the plants they gathered in the surrounding countryside. Yellows and greens came from nettles and cow-parsley, reds from ladies-bedstraw, and mauves from damsons and sloes.

Indeed, it was probably the dyers of Suffolk who first stumbled upon the idea of Suffolk Pink – an exquisite example being the pink cottages by St Mary’s Church in the village of Cavendish. The Suffolk Pink concept has now become so popular that a new variety of apple (discovered in Suffolk, of course) has been named for it.

Traditionally, though, it is a style of decoration: some have diamond-paned windows and oversailing upper storeys. Others are medieval moated halls, or cottages with low doors and steep thatched roofs. What they all share is their colour – pink. Shell-pink, rose-pink, geranium, even raspberry.

Centuries ago, these pink shades were created by adding natural substances to traditional lime whitewash. The cottager might perhaps stir in some elderberries – small black globes that release an amazing carmine red – or dried blood, or crumbled red earth.

Long Melford’s wealthy burghers also built the longest church in Suffolk – the amazing Holy Trinity. The size of a cathedral, it is as splendid inside as out. It contains, among other treasures, Suffolk’s largest collection of medieval glass.

Most of this glass commemorated the Clopton family, who lived in the village’s Kentwell Hall. A large brick mansion, Kentwell is essentially Tudor, with a Gothic centre block. Its latest owners insist that it is no stately home, just a family dwelling – albeit a very unusual one.

Kentwell has moats as well, and so do many smaller old Suffolk houses. By the 1500s, moats had become popular ornamental features and although many of Suffolk’s smaller moated houses are not open regularly to the public, although many offer private tours by arrangement. However, some have exquisite gardens which they do open during the summer months, such as those at Helmingham Hall, for example, home of the Tollemache family for 500 years. Here, there are two drawbridges which are pulled up every night as they have been since 1510, and the hall reverts to being an island, protected by its wide moat.

The historical gardens at moated Otley Hall, just north of Ipswich, are open by arrangement, and they include such curiosities as a croquet lawn and a nuttery. The gardens of nearby Heveningham Hall are also often open, and they contain many secret bridges and tunnels, as well as an elaborate parterre.

Parterres, popular in the 16th and 17th centuries, capture the curlicued decorative style of this period perfectly. They are hard to create, hard to maintain, and you cannot use them for much; so they made a perfect status symbol.

So, too, did the pargeting which became popular in Suffolk and adorned the walls of so many Suffolk houses. First seen around Henry VIII’s time, this elaborate custom-made plaster decoration has undergone something of a revival in recent years, although few modern displays can equal the best of the old ones.

In fact, gorgeous though pargeting looks, expert Tim Buxbaum believes that the craft developed partly as a way of covering up second-rate timbering or untidy new extensions on the outside of houses. “Coating the structure with a decorative coat of plaster was a good way to give an old building a new lease of life,” he says.

Buxbaum, who runs a conservationist architectural practice in Lower Ufford, draws special attention to the Ancient House in Ipswich, one of the finest surviving examples of pargeting in the country.

Commissioned in the 1600s by Robert Sparrowe, a widely travelled spice merchant, the house carries representations of Neptune with a trident, riding a sea-horse, St George and the Dragon, and Atlas carrying the world upon his shoulders – and that is just a fraction of its ebullient imagery.

Suffolk’s churches offer an exterior contrast to its ornate or colourful houses. One of the most famous Suffolk churches is Holy Trinity, Blythburgh, near the coast. It is full of light yet also shimmers with mystery. Inside, its wooden roof is covered in carved angels. Not far away, at Huntingfield, the rector’s wife, Mildred Holland, hitched up her skirts, climbed onto scaffolding and lay flat on her back for eight months in the 1860s to paint a stunning, Pugin-esque masterpiece of Victorian Gothic angels all over the ceiling.

In contrast, the parish church of St Peter and St Paul of Lavenham is typical of the wool churches of the county – completed by 1530. After visiting the church, stroll down the hill into the town, which has nearly 350 listed buildings. It’s regarded as one of the finest surviving medieval towns in England. Some parts of the town must still look much as they did when Elizabeth I made a grand state visit in 1578.

Indeed, when Robert Louis Stevenson visited Lavenham in 1873, he thought it looked, even then, like “what ought to be in a novel.” Now, of course, he would be imagining Angelina Jolie in a movie. Which all goes to show that times may change, but Suffolk does not.

Editor’s choice

Invitation to View allows small groups of visitors a great chance to see private historic houses which are not otherwise open

Constable and Gainsborough came from Suffolk and drew inspiration from the landscapes. Admire Constable’s unspoiled Flatford Mill near East Bergholt, with the Hay Wain’s famous Willie Lott’s Cottage. Visit the nearby National Trust museum and Gainsborough’s House museum in Sudbury which has a huge collection of the painter’s works.

The Great House (5-star), Lavenham: 15th-century restaurant with rooms on Lavenham’s Market Place, across from the Guildhall

The Suffolk Punch Trust in Hollesley: visitor centre and museum for these working horses with the longest written pedigree in the world

Theatre Royal, Bury St Edmunds: beautifully restored Georgian theatre, one of the earliest theatres in the country

The Swan at Lavenham (4-star), The Old Bar has a collection of memorabilia from American airmen stationed at Lavenham Airfield during World War II

Learn more about our Kings and Queens, castles and cathedrals, countryside and coastline in every issue of BRITAIN magazine

The post History of Suffolk county’s architecture appeared first on Britain Magazine | The official magazine of Visit Britain | Best of British History, Royal Family,Travel and Culture.

Britain Magazine | The official magazine of Visit Britain | Best of British History, Royal Family,Travel and Culture https://www.britain-magazine.com/features/history/suffolk-architecture/

source https://coragemonik.wordpress.com/2020/03/25/history-of-suffolk-countys-architecture/

0 notes

Text

Risibly dressed stereotypes

What is a person, and how are they manifest in their biography? Jane Austen had an answer to this question, which she presumably thought too obvious to proffer explicitly, but which is evident in the kinds of novels that she wrote, and the ways in which her characters inhabit them. Her assumptions inform her own work, and also that of the vast majority of novelists that have come after her, in many languages, through many forms of creative practice, down to the present day. This view of personhood, implicit in any claim to mimetic accuracy for Realist fiction, is not something I necessarily share, although it is not without its merits, but it is something I engage with on a daily basis. It’s the commonsense view, of a person as something that is found inside a human body, and which may be understood more or less accurately through speech attributed to that body. A whole set of assumptions about the shapes of human lives, and what is to be valued in human behaviour come as part of the package, and although Austen clearly did not invent these notions, her novels have been important instruments in conveying them to successive generations of the middle classes. This is not to suggest that I do not see any value or merit in such ideas, simply that I approach them critically, and that I do not take them as given. The question of what makes a human subject is one on which much remains to be said, but the power and cultural persistence of these assumptions makes them ideal targets for satire.

I didn’t start going to live comedy until Spawn was old enough to announce that comedy was her thing, and that she’d like to see some. Around this time we began taking a regular summer trip to Glasgow, where we have friends who were kind enough to provide us with holiday accommodation when we were close to penniless. I think it was on our second or third trip to Glasgow that we realised that a) Edinburgh is quite close, and b) it hosts a moderately well-known comedy festival in August. Thus began my exposure to stand-up, impro, and all the other delightful forms that comedy takes, and with it a family tradition that continues nearly uninterrupted to this day. On our second year as Fringe-goers we saw a rather entertaining show, in a pub on West Nicolson Street, in which the performers extemporised a play in the manner of Jane Austen, based on titles suggested by the audience. It was funny, and six years later we decided to see it again.

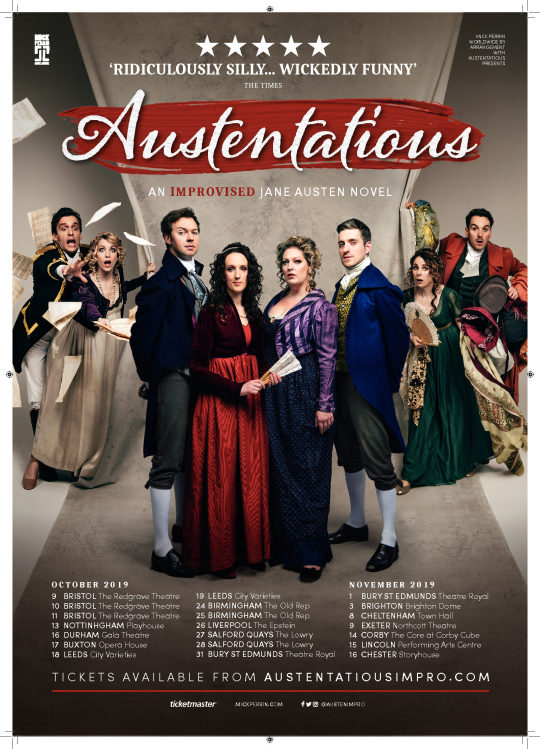

The cast of Austentatious no longer perform their show in The Counting House, an upstairs venue at the Pear Tree; now they are at McEwan Hall, the graduation hall of Edinburgh University, and one of its grandest spaces (in which Spawn sometimes sits exams). I had thought for some time that it would be worth returning to this show (perhaps several times) to see what the performers could do with the different suggestions that came their way, but by the time we got round to it the show’s reputation had obviously blossomed. The mock-Italian-baroque surroundings in which the much-increased audience are entertained could hardly be a better fit for the show, although they are significantly obscured by black cloths, presumably hoisted to tame the acoustics of a space designed to carry an untrained voice to its furthest recesses. The show still seems to work in much the same way, and it’s to the cast’s credit that their performance retains the intimacy and domesticity that it had in its humbler venue.

After requesting suggested titles from the audience and rejecting two, the ensemble begins to improvise on the basis of the third. This is something of a ruse, however, and both of the rejected titles are incorporated into the themes of the narrative. This may sound clever enough, but the performers also somehow manage to intertwine the various themes into something resembling a plot, with a deliberate and logical denouement. Clearly Jane Austen novels have plots which can be treated as formulae, into which any selected material can be slotted, and there are easily lampooned character types which are re-used in her narratives, but it would be interesting to watch a few consecutive shows, and see how much material is retained from performance to performance.

Clearly what emerges from the dramaturgical scenario is predominantly very silly. However, it’s far from pure whimsy, and although there are plentiful references to contemporary culture, the period atmosphere and Regency social tensions are maintained. The most compelling humour comes from the tension between notions of ’then’ and ‘now’, and in the improvisation we saw there was quite a sophisticated exploration of the parallels between social status in Regency England and contemporary social media – a garden full of followers all giving you the thumbs-up through your bay window could be pretty inconvenient! Of course the characters in such an improvised drama are stereotypical, but given the relatively narrow range of social behaviours to which individuals were expected to conform in Austen’s time, it might be suggested not only that Austen’s own characters are stereotypes decorated with distinctions, but that it was probably necessary for members of the gentry to act out those stereotypes, even when they were not confined to the pages of a book. In fact, I would argue that people have been required to perform one of a few clear generic types in most social contexts historically. The satirical insight that Austentatious offers, and which arguably makes it so funny, is that you can dress these stereotypes up with any kind of ridiculous surface features, and they remain recognisably the characters from a Jane Austen novel.

0 notes