#based off one of jokus sketches

Text

[ 12/21 - happy birthday apple twins ]

Dreamtale belongs to @jokublog

#cloudtale art#utmv#dream sans#dream!sans#nightmare sans#nightmare!sans#dreamtale#their birthday is tomorrow for me actually#but uhhhh yep!#based off one of jokus sketches

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

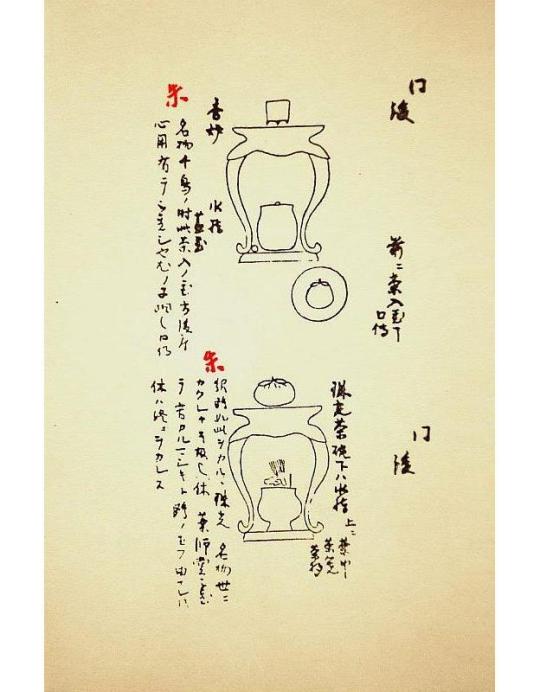

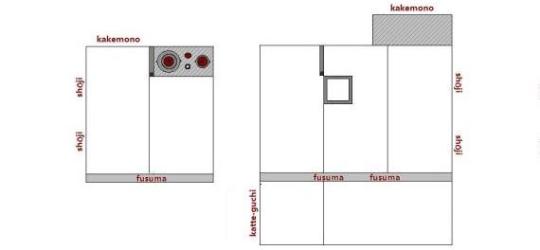

Nampō Roku, Book 4 (22): Mitsu-kugi [三ツ釘].

[The writing reads: (on the right) mitsu-kugi¹ mitsu nagara kake, mata naka wo hazusu-koto² ku-den ta-ta³ (三ツ釘 三ツナカラカケ、又中ヲハヅスコト口傳多〻); (on the left) mitsu-kake oki-mono ku-den⁴ (三ツカケ置物口傳).]

__________________________

¹Mitsu-kugi [三ツ釘].

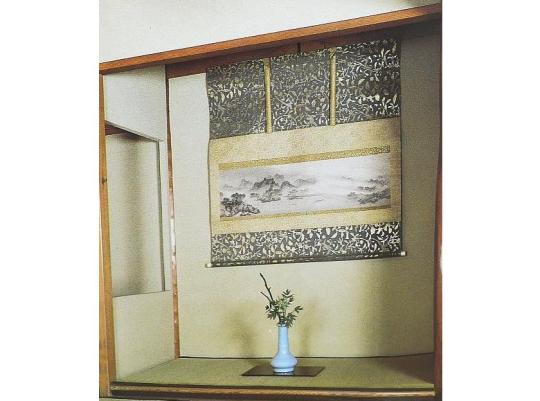

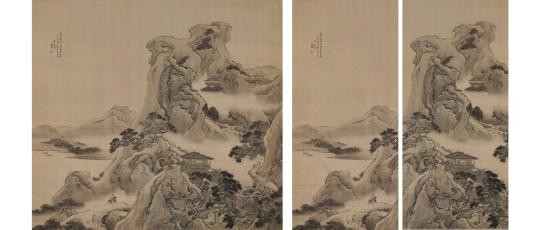

This refers to an exceptionally wide kakemono that, for safety (due to its weight) has the kake-o [掛緒] attached to the upper half-roller by four metal kan [鐶] rather than the usual two. The kan are indicated by the arrows in the following photo (the maki-o [巻緒] -- the cord used to tie the scroll when it has been rolled up -- has been pulled as far to the left as possible, so it does not complicate the image).

It was intended that scrolls of this sort should be hung from three hooks, rather than just one, and the toko was supposed to be modified accordingly.

Above is an example of this kind of scroll, hung in a 6-shaku wide tokonoma. The work shown is known as A Fishing Village in the Glow of the Setting Sun [漁村夕照圖], attributed to the Sung period monk-artist Muqi Fachang [牧谿法常, 1210~1269], which was one of Ashikaga Yoshimasa’s treasures (the scroll still features the original mounting that was designed for Yoshimasa).

²Mitsu nagara kake, mata naka wo hazusu-koto [三ツナカラカケ、又中ヲハヅスコト].

Mitsu nagara kake [三つながら懸け] means "while it is [usual] to hang [the scroll] from three [hooks]...."

Mata naka wo hazusu-koto [又中を外す事] means, "then again, there is the case where the middle [hook] is unfastened."

While it was originally intended that scrolls of this sort should be hung from three hooks (for safety reasons), it is also possible to hang the scroll from the outer two hooks*, while leaving the middle one off.

Shibayama Fugen quotes from Book Seven of the Nampō Roku: “the argument that a large yoko-mono† should be suspended from three hooks is well-informed. The important point is that the cord [from which] a meibutsu scroll [is suspended] should be drawn up [onto hooks] at three places (as it is shown to be hanging from three hooks in the upper sketch). In other words, it should be hung from all three [hooks].

“In the case of an ordinary [scroll], the middle [hook] is detached, so that it is suspended from two hooks (this is as shown in the lower sketch).

“But again, at night, an ordinary scroll [should be] suspended at three points‡.”

__________

*This was understood to be a wabi action by the machi-shū chajin of the Edo period. As a result, the custom arose, at that time (when all things were being codified into sets of shin-gyō-sō [眞行草]), of only hanging such scrolls from the middle hook, leaving those on either side off (this also allowed such scrolls to be hung in an ordinary tokonoma without having to bother about the need for three hooks attached to the back wall). There is no pre-Edo precedent for this sort of behavior, however.

When this idea became generally accepted, the system was codified as follows:

◦ hanging the scroll from three hooks was called shin [眞];

◦ hanging the scroll from the outer two hooks, while not using the middle hook was gyō [行];

◦ hanging the scroll from the middle hook, while leaving it unsupported by the outer two hooks, was considered sō [草].

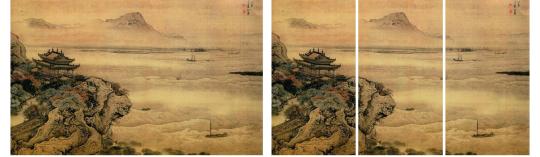

†Yoko-mono [横物] means a horizontal scroll -- one that is significantly wider than it is from top to bottom (the painting shown below measures 3-shaku 7-sun 5-bu wide by 1-shaku 1-sun 5-bu). These extremely wide yoko-mono were usually paintings removed from horizontal picture scrolls that were subsequently mounted as hanging scrolls (as much for preservation reasons as so they could be appreciated more effortlessly).

The sets of the Eight Views of the Hsiao and Hsiang are several such collections that were made from long, horizontal picture books depicting these famous Chinese scenes (arranged in order, as if the viewer were taking a tour down the rivers on a boat). The panel shown above, known as Evening Bell at a Smoke-enshrouded Temple [煙寺晩鐘圖] is believed to have been painted by Muqi Fachang (the seal in the lower left-hand corner indicates that it was part of the shōgunal collection during the Muromachi period, however, and has nothing to do with Muqi; the artist’s signature would have been found only at the end of the book, though apparently that fragment has been lost).

‡This, because all things must be done more carefully at night, on account of its being difficult to see.

◎ When a scroll of this type is being hung, first the cord is lifted on to the middle hook. Then the right side is lifted up, to engage the right hook. And finally the left side is elevated so that it may be slipped over the left hook. If, then, the intention is that the scroll be suspended only from two hooks, at the end the middle hook is disengaged, allowing the scroll to settle onto the two outer hooks. This, too, was one of the important ku-den associated with the mitsu-kugi.

It is because of this extra step that even an ordinary scroll was left hanging from all three hooks at night.

³Ku-den ta-ta [口傳多〻].

The ku-den that survived to Shibayama Fugen’s time are explained in the other footnotes above, and below, as appropriate.

⁴Mitsu-kake okimono ku-den [三ツカケ置物口傳].

This line means “[with respect to] the oki-mono when [the scroll] is hung from three [hooks], there is a ku-den.”

Shibayama Fugen explains that, when the scroll is hung from three hooks, the rules* governing the oki-mono are derived from the case where three scrolls were hung as a unit†.

But when it is hung from only two hooks, then the rules are taken from the case where two scrolls are hung simultaneously‡. This is the other exception to which Tanaka Senshō referred in his comments that were quoted in the previous post.

In the former case, based on the san-haba tsui [三幅對], it would seen that the oki-mono should be placed toward one side (so that it was in front of one of the inner pair of kan; while in the latter, where the precedent is the ni-haba tsui [二幅對], it would be located in the middle of the tokonoma. But, in both cases, with the caveat that the oki-mono not obscure any part of the scroll. The photo shown under footnote 1 illustrates what this means (the flower arrangement does not rise high enough to hide any part of the mounting)**.

___________

*When three scrolls were hung at the same time, the rule was that either a naga-joku [長卓] bearing the mitsu gu-soku [三具足] could be arranged in front -- possibly with a pair of larger rikka [立華] arrangements placed at both ends of the table -- if the subject matter was of a religious nature; or, in the case of paintings with a secular theme, that two rikka could be located in front of the empty spaces between the three scrolls.

When two scrolls were hung at the same time, one rikka was located in the space between them.

In all of these cases, it was important that none of the objects displayed in the toko would obscure any part of the scrolls.

†Indeed, the original sets of three scrolls were apparently made by cutting such a large single painting into three or more sections -- for the purpose of conservation (often because the intact work had begun to deteriorate).

In a historical sense, this is how the precedent for hanging multiple scrolls at the same time came to be established. Paintings that depicted a central actor (many portraits of the Buddha were -- and still are being -- subdivided in this way, with the central panel featuring the Buddha's portrait, while those on the right and left featured his followers or the other components of the scene in which he had been posed), or one the subject matter of which would lend itself to be divided into equal parts, would have to be cut into three pieces.

‡In this case, a wide painting was also the original source for two scrolls that were hung as a unit -- into how many parts such a piece could be cut depended upon the composition.

A work whose visual elements were concentrated on the left and right -- as is commonly seen in many classical paintings from the continent -- could better be cut in the middle (without the loss of anything essential to the composition), as shown in the above example.

Paintings by famous continental artists that could not be divided into scrolls in this way were sometimes used to paper the doors of cupboards (or even fusuma).

**Even though supposedly painted by a monk, A Fishing Village in the Glow of the Setting Sun is a secular-themed composition. Thus only a floral arrangement is displayed before it, rather than the mitsu gu-soku.

0 notes

Text

Nampō Roku, Book 3 (18.23): the Chū-ō-joku [中央卓], Part III.

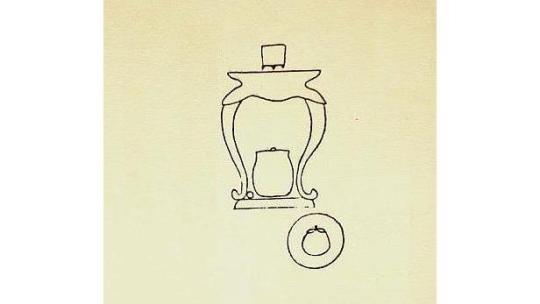

18.23) The chū-ō-joku [中央卓]: two additional arrangements for the goza¹.

[The writing reads: (to the right of the upper sketch, above) onaji (同)², go (後)³; (below) mae ni chaire oku-koto ku-den (前ニ茶入置事口傳)⁴; (to the left of the upper sketch) kōro ・ mizusashi ・ futaoki (香炉・水指・蓋置)⁵; shu ・ meibutsu Chidori no toki, kono chaire no oki-kata goza kokoro-yō arite kake-okushi nari (朱・名物千鳥ノ時此茶入ノ置方後座心用有テ被置シ也)⁶, mottomo shisai nari, kuden (尤ノ子細也、口傳)⁷; (to the right of the lower sketch, above) onaji (同)⁸, go (後)⁹; (below) Shukō chawan, shita ha mizusashi, ue ni chakin ・ chasen ・ chashaku (珠光茶碗、下ハ水指、上ニ茶巾・茶筅・茶杓)¹⁰; (to the left of the lower sketch) shu ・ Jōō gotoshi wo karuru, Shukō no meibutsu yo ni kakure naki yue nari (朱・紹鷗如此ヲカルヽ、珠光ノ名物世ニカクレナキ故也)¹¹, (Ri)kyū no Yakushi-dō kake-okite, kurushikaru majiki to Jō(ō) no tamau yori naredomo, (Ri)kyū ha owari ni okarezu (休ノ藥師堂被置テ、苦カルマシキト鷗ノ玉フ由ナレトモ、休ハ終ニヲカレス)¹².]

_________________________

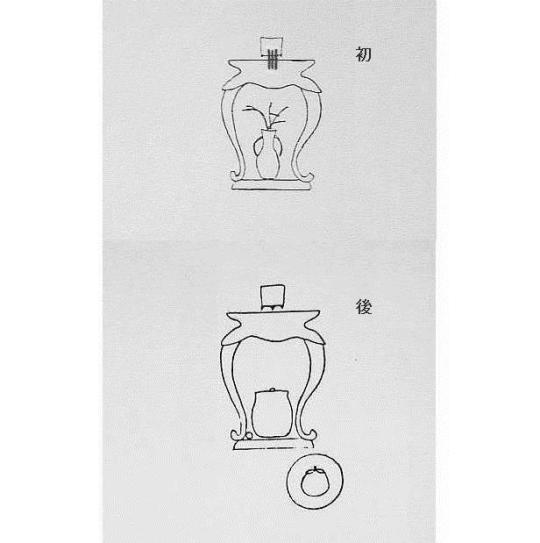

¹The upper arrangement is for an occasion when incense will be appreciated after the service of tea has been concluded; while the lower sketch shows the chū-ō-joku as arranged when incense will have been appreciated after the sumi-temae*. These will be compared with the relevant† shoza kazari in my commentary, below.

__________

*While it could be argued that this could also be used during a chakai when incense was not being appreciated at all, in the context of the preceding two installments, it seems most likely that Jōō was thinking in these terms -- otherwise he would have considered this possibility in his other arrangements.

As mentioned before, the chū-ō-joku was first used for chanoyu by the Shino family. Consequently, it is very likely that Jōō considered it always appropriate for incense to be appreciated during those chakai where this tana was used -- especially during the period (his middle period) when this densho was written.

†Internal evidence, regarding the way that Jōō constructed this brief document, leads directly to the conclusion that he envisioned these as alternate goza kazari for the two cases that he illustrated in the first two parts of the chū-ō-joku material.

²Onaji [同].

“The same.”

In other words, the upper sketch shows the chū-ō-joku -- as on the previous two pages of sketches.

³Go [後].

The chū-ō-joku would be moved from the tokonoma to the utensil mat, and this arrangement would be assembled, during the naka-dachi. Consequently, this is what the guests would see when they returned to the tearoom for the goza.

Specifically, the way this densho has been formatted implies that this goza arrangement would follow a shoza kazari like that shown in the first of the three chū-ō-joku pages (Nampō Roku, Book 3 (18.21): the Chū-ō-joku [中央卓], Part I*) -- where the chū-ō-joku was displayed in the tokonoma during the shoza, with a meibutsu kōro on top, and a hanaire below. The tana would then be moved to the utensil mat during the naka-dachi, with mon-kō [聞香] following the service of tea, at the end of the goza.

___________

*The URL for that post is:

https://chanoyu-to-wa.tumblr.com/post/188393093318/namp%C5%8D-roku-book-3-1821-the-ch%C5%AB-%C5%8D-joku

⁴Mae ni chaire oku-koto ku-den [前ニ茶入置事口傳].

“There is a ku-den that addresses the matter of the chaire being placed in front of [the chū-ō-joku].”

According to Tanaka Senshō, the entire text of the ku-den is: meibutsu no kōro jō-dan ni agaru yue, chaire shita ni oki nari [名物ノ香炉上段ニ上ルユヘ、茶入下ニ置ナリ], which means “because the meibutsu kōro has been elevated to the upper level [of the tana], the chaire is placed below.”

It is unlikely that this “ku-den” existed very long before Tachibana Jitsuzan produced his copy of the document -- since the ancients were inclined to provide real information in their oral traditions, not just reiterate things that would be obvious from the written exposition. Doing things like this was an important facet of the Edo period, when the different schools attempted to make their traditions secretive and mysterious*.

___________

*Because these “schools” had, rather suddenly, been turned into businesses, the only way they could guarantee their revenue would be to come up with things that the interested would be willing to pay for, and secret information separated from the general public by a pay wall would be an excellent idea, irrespective of how practically meaningless the “ku-den” actually turned out to be.

The modern system is an excellent example of the lengths to which this process could proceed: the tea candidate is required to purchase a menjō, which is nothing more than official permission to study the material in question (not, as in many other activities, such as flower arrangement, a certificate of attainment, received after passing a test). He or she then begins the process of training by paying an officially sanctioned teacher -- even when, as in the case of the lower menjō, all of the material is already freely available as printed books and videos in the local book store or public library -- and the process ends when the student is permitted to purchase the next menjō. The attainment of the previous body of information is assumed, to be sure; but this is hardly assured (and I personally know of many chajin in Japan who hold menjō for temae that they could not perform if their life depended on it).

⁵Kōro ・ mizusashi ・ futaoki [香炉・水指・蓋置].

These are the objects arranged on the chū-ō-joku in the illustration. The kōro is on the ten-ita, and the mizusashi and futaoki (the disproportionately small circle, adjacent to the base of the left leg of the tana) on the ji-ita.

⁶Shu ・ meibutsu Chidori no toki, kono chaire no oki-kata goza kokoro-yō arite kake-okushi nari [朱・名物千鳥ノ時此茶入ノ置方後座心用有テ被置シ也].

Shu [朱] means that the entire text of the kaki-ire [書入] was written in red ink on the original document (even though Jitsuzan copied it in black ink).

The kaki-ire itself, meanwhile, means “on an occasion when the meibutsu Chidori [kōro] is [being displayed on the ten-ita of the chū-ō-joku], one must be mindful of the way that this chaire is placed out during the goza.”

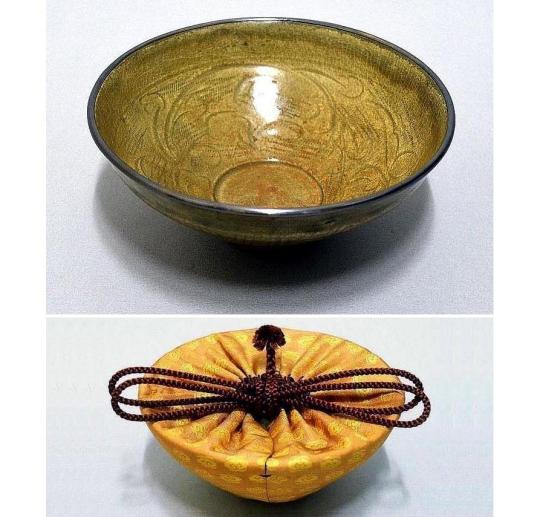

The meibutsu Chidori kōro is shown below.

This kōro has been considered to be the highest-ranked te-kōro [手香爐] (an incense burner intended to be held in the hand while sniffing the incense)* since at least the Higashiyama period. It was subsequently owned by Jōō -- who is said to have provided the lid with its handle shaped like a plover (= chidori [千鳥], a shore bird that lives in the intertidal zone).

___________

*According to Book Six of the Nampō Roku, the purpose for which a small censer was intended can be understood from the spacing of the three feet (which often do not always contact the base on which the kōro is rested).

When they are equidistant, the kōro was intended for display on a tana. But when there is a larger space between the front foot and the foot on the left, the censer was intended to be rested on the left palm, and used for appreciating incense directly.

The larger distance on the left side allows the fingers of the left hand to be inserted, so that the thickened bottom of the kōro (which minimizes heat transmission to the point where the censer is comfortable to hold in the bare hand) rests on upward-facing palm. The three feet, then, guide the hand (and often those on the left and in front are at the sides of the hand, rather than resting upon it, while the right leg fits into the space where the third and fourth fingers branch off from the palm)

⁷Mottomo shisai nari, kuden [尤ノ子細也、口傳].

“The details are inherent [in the relationship between the meibutsu kōro and the chaire], [this is contained in] a ku-den.”

Once again, Tanaka Senshō includes the ku-den, as it was transmitted to him by a person who was a member of the inner circle of the Nampō Roku scholars affiliated with the Enkaku-ji: ku-den to ha Chidori no kōro, shoza, joku no ue chū-ō ni okuretaru yue, goza ni chaire ha tatami ni okuretaru koto mottomo no koto nari [口傳トハ千鳥ノ香炉、初座、卓ノ上中央ニ置レタル故、後座ニ茶入ハ疊ニ置レタルコト尤ノコトナリ]. This means “with respect to the ku-den, because, during the shoza, the Chidori no koro is placed in the exact center of the upper [shelf] of the [chu-o-]joku, during the goza the chaire should be placed on the tatami: this is an innate fact.” (I have put the important phrase in bold face in both the Japanese original, and the English translation.)

In other words, given the standing of the kōro*, it is natural that it takes precedence over the chaire, and so the inherent state of things is demonstrated by placing the chaire on the mat.

___________

*The argument seems to revolve not only around the fact that this was such a special censer, but also because a kōro releases perfume (which was considered to be a whiff of the atmosphere of Amida’s Pure Land), while the chaire -- any chaire, no matter how great -- is just a container for food.

One interpretation of the passage in the Lotus Sutra from which the idea for sadō [茶道] (meaning chanoyu when used as an exercise in motion meditation) arose uses tea (literally, “a medicine with a wonderful fragrance, color, and taste”) as a sort of allegory for samadhi. But this is a verbal flourish, and not a statement of fact. Samadhi can be attained through chanoyu, but drinking the tea itself is irrelevant to the process.

⁸Onaji [同].

Once again, the lower sketch also shows the chū-ō-joku.

⁹Go [後].

And this, too, is an arrangement for the goza of a chakai.

As in the upper sketch, the implication is that this goza arrangement follows the shoza were mei-kō (in a Shino-bukuro) was displayed on the ten-ita when the guests entered the room for the shoza (see the post entitled Nampō Roku, Book 3 (18.22): the Chū-ō-joku [中央卓], Part II*). In this case, the chū-ō-joku would be arranged on the utensil mat from the start of the chakai, and the appreciation of incense would take place during the shoza, following the sumi-temae.

___________

*The URL for that post is:

https://chanoyu-to-wa.tumblr.com/post/188455690861/namp%C5%8D-roku-book-3-1822-the-ch%C5%AB-%C5%8D-joku-%E4%B8%AD%E5%A4%AE%E5%8D%93

¹⁰Shukō chawan, shita ha mizusashi, ue ni chakin ・ chasen ・ chashaku [珠光茶碗、下ハ水指、上ニ茶巾・茶筅・茶杓].

“The Shukō-chawan [is displayed on the ten-ita]; [and] below is the mizusashi, on top [of which] are the chakin, chasen, and chashaku.”

The Shukō-chawan was destroyed in the fire that was set by Mori Ranmaru [森蘭丸; 1565 ~ 1582] (Oda Nobunaga’s personal attendant), to destroy the shoin of the Honnō-ji, so that Akechi Mitsuhide could not collect and display Nobunaga’s head, following his coup d’état.

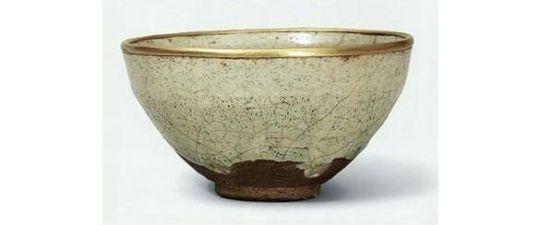

While the original chawan that had belonged to Shukō was lost, several other chawan of the same type have survived, one of which is shown above and below.

The only real difference between the bowls (all of which were brought from China at the same time -- likely originally purchased as a bundle of 10 bowls, for restaurant use) was the number of marks on the outside, caused by hitting the clay with a long broom-like spatula made of split bamboo, to shape it on the mold over which the clay had been draped. The purpose was to mass-produce bowls of identical size -- which were made for serving noodles in road-side food stalls.

While Rikyū placed the Shukō-chawan on top of a large, red-lacquered sakazuki [盃] (which he handled like a temmoku-dai), this usage was unique to him. Jōō used the Shukō-chawan without any kind of base -- as had the previous users, back to Shukō himself.

¹¹Shu ・ Jōō gotoshi okaruru, Shukō no meibutsu yo ni kakure-naki yue nari [朱・紹鷗如此ヲカルヽ、珠光ノ名物世ニカクレナキ故也].

Once again, shu [朱] means that this passage was written in red ink, in the original document.

The kaki-ire means “Jōō placed [the Shukō-chawan] like this, because Shukō’s meibutsu [chawan]* was renowned throughout the world.”

It is important to remember that the Shukō-chawan was already damaged when it came into Jōō’s possession (the small crack had been painted over with same-colored lacquer, to obscure it -- but its existence was well known to the chajin of Jōō’s day). This fact stands in the background, and is the reason why this treatment (of displaying the Shukō-chawan on the chū-ō-joku) was so remarkable†.

___________

*This chawan was “renowned” and “meibutsu” because it appears that it was the first kae-chawn [替茶碗] (a large chawan, originally used only to clean the chasen, using cold water, at the end of the temae) to have been used to serve koicha to his guests.

†In Jōō‘s period, and before, as soon as a utensil suffered any sort of damage, it was considered no longer appropriate for use in chanoyu. The Shukō-chawan, then, was the exception -- because it had been used by Shukō himself -- and part of the reason it was meibutsu was because it established not only the precedent for using (slightly) damaged pieces, but also the temae by which such things could be handled without damaging them further. All of this forms the background to this episode.

¹²(Ri)kyū no Yakushi-dō kake-okite, kurushikaru majiki to Jō(ō) no tamau yori naredomo, (Ri)kyū ha owari ni okarezu [休ノ藥師堂被置テ、苦カルマシキト鷗ノ玉フ由ナレトモ、休ハ終ニヲカレス].

“[Ri]kyū [at first] arranged his Yakushi-dō [temmoku] in this way. But because Jō[ō] said that it was difficult [for people to accept*], it was better not to do it in this way. In the end, [Ri]kyū decided not to place it like this.”

The Yakushi-dō temmoku [藥師堂天目], shown above, was fired at the Seto kiln, and so was an early example of what came to be known as Shino ware (Shino yaki [志野焼]†) in the Edo period.

Rikyū used this chawan on one of the meibutsu kazu-no-dai [數ノ臺]‡ known as the Hotta-dai [堀田臺].

___________

*Jōō’s argument -- at least based on the context of this entry -- seems to be that, because the Yakushi-dō temmoku was not well known by the chajin of that day, or because it had been newly made in Japan, it was not appropriate to display it as a mine-suri on the chū-ō-joku. Thus, Jōō’s objection might reflect the traditional prejudice that Japanese chajin have always held against locally made/newly made objects vis-à-vis antique or imported pieces.

It is important to understand that this episode appears to date from Rikyū’s younger years -- perhaps shortly after Jōō had accepted the young man as his disciple (and so several years before he commissioned Rikyū to visit the continent and bring back carefully selected tea utensils for resale in Japan).

Also, while the shira-temmoku are listed as the highest class of temmoku in the Yamanoue Sōji Ki [山上宗二記], this does not mean that they were so regarded at the time when they were first made (the white temmoku seem to have all been made to Jōō’s order, and so would date from his middle period -- as a distinctly wabi , locally made, alternative to the imported Kenzan bowls).

†Though this is not entirely clear from the surviving historical documents, it appears that this name was given to the white-glazed version of Seto ware because many (or famous) examples of this type of pottery were owned/cherished/favored by the Shino family -- the same family who first used the chū-ō-joku during the service of tea.

‡The kazu-no-dai were rather ordinary black-lacquered temmoku-dai, albeit imported from China.

These dai were originally made to hold bowls of heated sake, in China, where they were used in drinking houses (the red-lacquer markings on the bottom of many of these dai indicate the drinking house for which they were made). That these dai were elevated to such an important position in Japan reflects the rarity of utensils that were imported from the continent during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries.

Most likely, the Yakushi-dō temmoku was placed on top of the Hotta-dai when Rikyū displayed it on the chū-ō-joku.

==============================================

I. The upper arrangement.

It should be understood that the implication, from the way this densho was constructed, is that this arrangement for the goza (marked go [後] in the digitally modified sketch, below) would follow the shoza arrangement (marked sho [初]) where the chū-ō-joku was displayed in the toko, with the meibutsu kōro above and a hanaire below, as shown below:

During the naka-dachi the tana was moved from the tokonoma to the utensil mat. While the meibutsu kōro* was again placed on the ten-ita, the hanaire was replaced by a mizusashi, and the futaoki was also added to the arrangement.

While nothing is said, the chū-ō-joku was apparently placed in the center of the utensil mat, with the bon-chaire associated with the second kane from the heri. Shibayama Fugen comments that displaying the bon-chaire in front of the right side of the tana (rather than centered on it) is a way to show added respect to the chaire†.

___________

*The ō-meibutsu [大名物] Chidori kōro [千鳥香爐] was one of the highest-class kōro of all times. It still survives to this day.

†We must remember that, originally, the ro was on the host’s left. In such a case, the bon-chaire is shown moved farther away from the ro, which, indeed, is the more respectful position, since the farther from the guests (and the dust which their movements raise), the purer the location -- though always keeping in mind the kane, and the chaire’s relationship with them. This densho dates from Jōō‘s middle period, when this kind of orientation (i.e., with the ro cut on the left) was still universally preferred.

The reasoning becomes confused when the ro is cut on the host’s right, yet the arrangement remains as shown in the sketch.

——————————————–———-—————————————————

II. The lower arrangement.

This sketch should be understood as following on from the same sort of shoza kazari (marked sho [初]) as seen in the installment that was published immediately before this one (once again, I have digitally modified the following sketch to reflect this idea) -- where mei-kō [名香] (enclosed in a kō-bukuro [香袋], or in a kōgō) was displayed on the ten-ita at the beginning of the gathering:

Here incense would be appreciated immediately after the sumi-temae (the tadon [炭團] having been put into the ro along with the rest of the charcoal); and tea would be served (using the Shukō-chawan) after the naka-dachi. This kind of arrangement is known as chasen-kazari [茶筅飾].

The way the modern schools arrange the objects (including the chashaku) on top of the mizusashi for chasen-kazari was derived from this sketch.

Aside from his recitation of the two ku-den (which do little more than restate the text of the kaki-ire), Tanaka Senshō has nothing to say about either of these arrangements.

0 notes

Text

Nampō Roku, Book 3 (1): the Origin of the 4.5-mat Room¹.

1) With respect to the 4.5-mat sitting room², it was created³ by Shukō. Because this was the shin-no-zashiki [眞座敷]⁴, tori-no-ko paper⁵ was pasted [onto the walls] to lighten [the interior of the room], and cryptomeria boards without frames⁶ were used for the ceiling. Small wooden shingles were used to cover the gablet-roof, and it had a one-ken [一間]⁷ toko. His treasured bokuseki by Engo [圜悟]⁸ was hung up, and he honored [his guests] by using the daisu [when he served them tea]⁹. Sometime later, [Shukō] cut a ro [in the floor], and the kyū-dai [弓臺] was arranged together with it.

In general, though objects of the sort that were [customarily] arranged in the shoin were [also] placed out [in this setting], their total number was reduced: [for example,] in the toko, a pair of pictorial scrolls¹¹ were hung -- or, naturally, just a single painted scroll could also be hung up. In front of this a small table [was set up], on which was an incense burner and a [pair of] hanaire¹². Or possibly a small flower-vase in which one variety of flower has been stood¹⁴. Or else writing paper and an ink stone, or a tanzaku-bako [短冊箱]¹⁵, or a [small] reading desk¹⁶. Or perhaps a bon-san [盆山]¹⁷, a ha-cha-tsubo [葉茶壺]¹⁸, or other things like that. Only things of this sort were displayed [in Shukō's room].

With the advent of Jōō, the yojō-han was modified here and there by removing the [wallpaper] to reveal the mud-plaster of the walls, while he also replaced the wooden pillars [that support the walls] with bamboo. He removed the koshi-ita [腰板]¹⁹ from the shōji, and replaced the black-lacquered sill at the bottom of the toko with one painted either with thin-lacquer, or he left [the sill] unpainted²⁰. This is said to be the sō-no-zashiki [草の座敷]²¹.

[Jō]ō²²did not display the daisu in that kind of room. When he felt like displaying the kyū-dai [弓臺], then the kakemono and the objects displayed [in the room] were similar to the things that Shukō had used. [But] when he [used] the fukuro-dana, [he displayed] a bokuseki in the toko; and except for the hanaire, nothing else was placed there.

Later [still], Sōeki²³ began to use a ko-yashiki that had a thatched roof²⁴ on every occasion²⁵. This was a manifestation of his practice of wabi²⁶.

Jōō's [yojō-han] zashiki, as a result [of this development], was [thenceforth] considered to exist somewhere between the shoin and the ko-zashiki. For this reason, when using the fukuro-dana, a certain flexibility is permitted²⁷.

In the above enumeration of the various objects displayed by Shukō, with respect to the piece of furniture [referred to as a] joku [卓], if something like a small flower-vase with a flower standing in it is excluded, any number of other things might be placed [on it]²⁸.

_________________________

¹This section, which is clearly spurious, does little more than reiterate details taken from Kanamori Sōwa's largely fictitious “history” of chanoyu*. The language of the entry is typical of the Edo period.

It is not really clear (from the surviving documents of his period) what Jōō and the chajin of his generation actually believed -- though the cha-kai [茶會], as it existed then (and now†), was a creation of Jōō (albeit based on the format of the Shino family's incense gatherings, which they referred to as kō-kai [香會]); and the intimate knowledge of this fact would surely have colored their perception of chanoyu’s earlier history.

The details of the 4.5-mat room, as described in this entry, had already been fixed much earlier than Shukō's period, since a room of this size had been considered appropriate for a man's personal living space according to the tenets of buke-zukuri [武家造]‡, the style of architecture favored by the military class, from which the shoin-zukuri [書院造] style (featuring shoin rooms with details such as are described here) had been evolving since the late Kamakura period**.

__________

*Sōwa, a daimyō with a scholarly bent and an interest in chanoyu (he had studied tea with Sen no Dōan), was commissioned to write this history by the Tokugawa bakufu, with the express purpose being to Japanize chanoyu, in order to create the precedent necessary to facilitate the bakufu’s sale of Hideyoshi’s collection of meibutsu tea utensils (and thereby raise the cash necessary to pay off the Tokugawa family’s war-debts).

As long as chanoyu was generally perceived to be an imported foreign (Korean) taste, the market for tea utensils was distinctly limited to the (mostly ethnic Korean) curio collectors (whose ranks had been thinned considerably as a result of Hideyoshi’s decimation of Sakai and Hakata in 1595, as punishment for their opposition to his failed invasion of the continent).

†Today the equivalent of Jōō's cha-kai is known by the name of chaji [茶事]. The reader is cautioned to keep this fact in mind, and not confuse Jōō's and Rikyū's usage with the modern chakai [茶会].

‡According to the twelfth century Hōjō Ki [方丈記]. The so-called hōjō [方丈], which means a room one jō square (one jō is 10 shaku long: rooms of this dimension predated the time when the floor came to be completely covered with tatami mats), was approximately the same size as a 4.5-mat room.

**While the word shoin [書院] is usually translated as “study,” its function was much more encompassing: the nobleman used the shoin not only as his personal sitting room (making it rather like a den), but he also slept, ate, washed, and dressed there, as well as using the room for the reception of intimate guests. The tokonoma in this room functioned as a jō-dan [上段] (the built-in equivalent of the mi-chōdai [御帳臺], or nobleman's “seat of estate”) on occasions when this sort of formality was needed when receiving persons of differing rank (the toko-gamachi allowed reed or gauze curtains to be suspended from it, to obscure the nobleman’s countenance from those whose rank did not permitted them to look directly at him).

²Yojō-han zashiki ha [四疊半座敷ハ].

The word zashiki [座敷] means a “sitting room.”

³Sakuji [作事] means to build, construct. According to this entry, Shukō was the first to build such a room (though this is patently false -- since, even in the context of chanoyu, Yoshimasa used a room of this sort for serving tea before Shukō even arrived in Japan from Korea).

⁴Shin-no-zashiki [眞座敷]: perhaps the interpretation of this expression as meaning “most formal [style of] sitting room” is called for by the context.

⁵Tori-no-ko kami [鳥子紙] is a kind of paper with one side finished to a hard texture resembling the surface of a chicken egg.

⁶Fuchi-nashi tenjō [ふちなし天井]. In the earlier period, the ceiling was constructed in such a way that it appeared to consist of a series of small panels surrounded by frames (this is usually called a coffered ceiling in English, and a classical Japanese example with elaborate gilding and painting is shown below, on the left).

The term fuchi-nashi tenjō [縁無し天井] means that the frames were eliminated: the ceiling now consisted of a series of flat boards, laid side by side (this style of ceiling, sometimes called kagami-tenjō [鏡天井], is shown above, on the right).

In the early days, the uniform surface invited the painting of clouds and dragons and other heavenly figures, usually in black ink; but by the Momoyama period, colors and gilding were also added. The example shown above is found in the Sūtra Hall of the Kiyomizu temple in Kyōto.

⁷Ikken [一間] means six feet. This was a tokonoma with what was essentially a full-sized tatami mat covering the floor.

⁸Engo no bokuseki [圓悟の墨跡].

This refers to the bokuseki that is known as the Nagare Engo [流れ圜悟] today*. This scroll is said to have been the first bokuseki ever used for chanoyu.

The scroll was written by the Chinese Chán (Zen) monk Yuán-wù Kèqín [圜悟克勤; 1063 ~ 1135], the editor of the Bìyán Lù [碧 巖 錄] (Heki-gan Roku; the Blue-cliff Records).

As has been mentioned before in this blog, this document was not intended to be used as a scroll, but was actually part of Yuán-wù’s lecture notes (he traveled around China giving lectures on the cases in the Bìyán Lù, and this is a fragment of the text of one of his lectures, which one of the attendees probably kept as a souvenir of the occasion.

__________

*This is the scroll that tradition holds was given to Shukō by Ikkyū Sōjun.

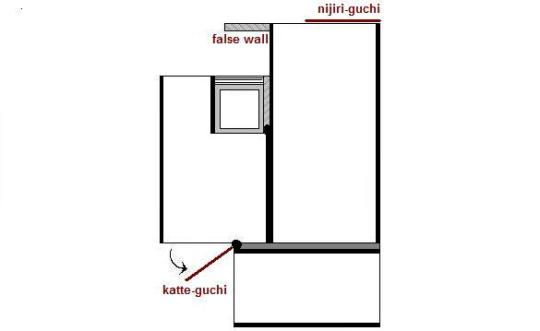

⁹In fact, Shukō appears to have used a sort of o-chanoyu-dana (perhaps missing a suspended upper shelf) to hold the utensils, rather than a daisu, as shown on the left in the sketch (below).

When his room, the Shukō-an [珠光庵] (in the Shōmyō-ji [稱名寺], in Nara), was reconstructed (the reconstruction is shown in the sketch on the right), this board-floored area was assumed to be the tokonoma (and so it was moved beyond the end of the guests’ mat, and enlarged to the size of the Sen families’ preferred toko for the small room, in keeping with the teaching of suki [数奇] -- which states that the guests must be provided with at least one full mat for their use), and an extra mat for making tea (featuring a daime-gamae situated at the end of an ordinary maru-jō, and so somewhat resembling the original version of the Tai-an) was added to what had originally been a two-mat residential cell. This board seems to have become (quite mistakenly) the precedent for the ita-doko [板床].

¹⁰Kyū-dai [弓臺]: this is an abbreviated reference to the kyū-dai daisu [及第臺子], shown below.

This tana, which was originaly made for use as a writing desk on the continent, has a ten-ita that is the same size as that of the large shin-daisu (measuring 1-shaku 4-sun by 2-shaku 9-sun 5-bu); however, because the ji-ita is smaller (in fact, it is the same size as the small shin-daisu, and measures 1-shaku 3-sun by 2-shaku 7-sun 5-bu), it could not be used with the furo (since the legs would prevent the host from raising or lowering the kan on the kimen-buro when necessary*).

Traditionally it is said that Jōō was the first person to use the ro, though the earliest documents seem to be rather confused on this point. It is possible that a hole was cut in a square board that replaced part of the floor, into which an iron ro-dan† was lowered to hold the fire, and this practice may have predated the appearance of Jōō by several decades.

__________

*In the early period, chanoyu was generally performed to serve tea to a single guest (who was technically taking the place of the Buddha, so that the tea would not be wasted). When this person was a nobleman, the kan were raised (so they lean against the neck of the furo) when he was present in the room, but lowered (so that they depend below the kan-tsuki).

†Or, more likely, an old cooking pot with the sides above the flange broken off. This seems to have already been in use on the continent by the more wabi of tea men, so it is possible that the practice arrived in Japan during the second half of the fifteenth century.

If so, then it may be that Jōō, rather than introducing the use of a sunken fire, may have been the first to use a mud-plastered cooking hearth of the sort found in the farmhouse kitchen.

¹¹Ni-fuku-tsui [二幅對] refers to a pair of scrolls that were intended to be displayed together. Sometimes they represented a larger work that had been cut in half (since narrower scrolls were much easier to preserve than excessively large ones), and sometimes separate works (sometimes by different artists) that came to be used together in order to evoke a scene*. Scrolls intended for this purpose were prepared with identical mountings.

In addition to pairs of paintings, the number of scrolls in a set sometimes exceeded five, or even eight. It is in light of this that Shukō's restriction to a pair becomes important.

__________

*Traditionally, one scroll should be a landscape, while the other should feature human subjects (generally representations of the Buddha, or esteemed monks) -- the idea being to figuratively locate the people in the landscape.

The scene was originally supposed to suggest a vision of the Buddha Amitābha's Western Paradise.

¹²Mae ni ha joku ni kōro, hanaire [前にハ卓に香爐、花入].

The incense burner was placed in the middle of the small table, with either a hanaire on each side, or (at night) a hanaire and a small candlestick. The idea was to reinforce the idea of a vision of the Western Paradise, where the air is said to be perfumed. The flower arrangements bring the scenery of the scroll paintings into the foreground.

¹³Arui ha ko-kabin ni isshoku-rikka [あるひハ小花瓶に一色立華].

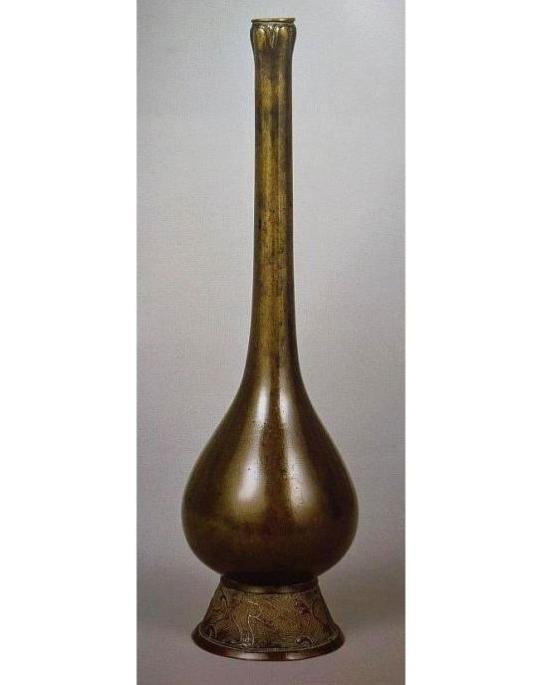

A ko-kabin [小花瓶] is the kind of flower container that Rikyū described (in his kaiki) as a hoso-guchi [細口].

Isshoku-rikka [一色立華] means a single type of flower is stood upright in the hanaire.

¹⁴Ko-kabin ni isshoku rikka [小花瓶に一色立華].

The meaning of this phrase, in this context, is unclear.

Ko-kabin [小花瓶] would seem to refer to a small bronze hanaire, one that is large enough to hold just a single flower. Rikyū's famous Tsuru-no-hito-koe [鶴ノ一聲] (shown below) is an example of the kind of vase referred to as a “ko-kabin” in classical works such as Nōami's Kun-dai Kan Sa-u Chō Ki [君臺観左右帳記].

The expression isshoku [一色], which literally means “one color,” was also used to mean one variety or type (out of two, or more, possibilities*).

However, while the name rikka [立華] usually refers to a highly stylized floral arrangement (intended to recreate a landscape in miniature), it would be physically impossible to arrange more than a single stem in a ko-kabin (at least if the word is being used in its classical sense); nor would it seem possible to create a rikka using only one variety of flower†.

While this is not the sort of mistake that Jōō (or Rikyū) would likely have made, it appears that whomever was responsible for adding this section to Jōō’s text was not so well informed. Thus, while I have interpreted the statement to mean that a single variety (isshoku [一色]) of flower (ka [華]) is stood (ritsu [立]) in the ko-kabin, this reading should be considered tentative.

__________

*In Book One of the Nampō Roku, the expression is used, relative to flowers, to mean one of the two possibilities -- which were the flowers of herbaceous plants, and the flowers of woody plants. Precisely how it is being used here -- and whether the usage is the same as previously or not -- is debatable.

†These highly mannered arrangements generally use some sort of long-lasting woody plant material to define the basic structure of the arrangement, which is then “filled in” with various other flowers. In the shoin setting, where the arrangement was often kept in the tokonoma for a considerable period of time, the woody material remains, while the herbaceous flowers are changed when they begin to wilt.

¹⁵A tanzaku-bako [短冊箱] was a special lacquered box in which a collection of tanzaku [短冊] (elongated pieces of paper on which poems were written) was kept. Some of the tanzaku may have already been used, while others were unused.

The tanzaku featuring poems were generally selected because they were appropriate to the occasion, and intended to inspire the guests to use the unused tanzaku for their own compositions.

¹⁶A bundai [文臺] was a small table (about the height of ones lap when seated on the floor) on which a book (or open scroll) was rested while reading it. A bundai could also be used when writing (in a situation where there was not a built-in writing desk available for this purpose).

¹⁷A bon-san [盆山] is a small stone naturally shaped like a mountain, arranged in a tray of rather fine white gravel, with the gravel shaped to resemble a beach and sand-dunes in front of the stone, and the waves of the distant ocean behind (according to a poem by Ashikaga Yoshimasa that is preserved in several of Rikyū's densho).

The bon-san known as Zan-setsu [殘雪], which was one of Yoshimasa’s personal treasures. The stone is shown resting on a Korean sawari [四分一] tray. (Sawari is a variety of bronze containing a certain proportion of silver. The purpose of the silver was to keep the bronze from oxidizing, so it would remain a pale golden color.)

¹⁸Ha-cha-tsubo [葉茶壺]: a large jar in which the dried leaves that will (eventually) be ground into matcha are stored.

¹⁹Koshi-ita [腰板] refers to a wooden panel at the bottom of a shōji (anywhere between 6-sun and 1-shaku or more high), that prevents a person sitting beside it from accidentally damaging the paper with their feet. By removing the koshi-ita, Jōō let more light into the room at floor level.

²⁰Toko no nuri-buchi wo, usu-nuri, mata ha shira-ki ni shi [床のぬりぶちを、うすぬり、又ハ白木にし].

Originally the sill of the toko was lacquered with shin-nuri (since only the homes of important persons featured a tokonoma*). Jōō modified this by either painting the sill with thin lacquer (usu-nuri [薄塗り]†), or by leaving the sill unpainted (shira-ki [白木]‡).

__________

*The original purpose of the tokonoma was to serve as a sort of jō-dan [上段], a place where the man of rank could sit when receiving people of a lower station than himself.

†There are two possible meanings for this:

- the black lacquer itself is thin, meaning that the variations in height of the grain can be perceived after the lacquer flattens (this is referred to as kaki-awase nuri [掻き合わせ塗り] today);

- or, the amount of iron powder (which colors the lacquer black) is limited or eliminated (resulting in something resembling tame-nuri [溜め塗り], which is technically a mixture of shin-nuri and Shunkei-nuri; or the honey-colored Shunkei-nuri [春慶塗り] by itself) -- here the lacquer itself is thinly colored, so the grain of the underlying wood-grain can be perceived through the lacquer (as if under glass).

In documents from the period, both the Hora-dana [洞棚] (on the left: it is painted with black kaki-awase-nuri) and the Jōō-dana [紹鷗棚] (on the right: this tana is painted with Shunkei-nuri) are described as being painted with usu-nuri.

‡Shira-ki specifically means wood with the bark removed. The word does not deal with whether the wood was squared, had the four faces shaved, or left in the round.

²¹Sō-no-zashiki [草の座敷]: in contrast to the shin-no-zashiki [眞座敷] (see footnote 4, above), the sō-no-zashiki would be an “informal” room.

²²Ō [鷗] is an abbreviation of Jōō's [紹鷗] name.

²³The name Sōeki [宗易], of course, refers to Rikyū. Sōeki was his Buddhist name; which, according to the custom of the day, he used as his professional name.

²⁴Kusabuki no ko-yashiki [草茨の小屋敷].

Kusabuki [草茨] seems to be cognate with the more commonly used (today) kusabuki [草葺], meaning a thatched roof.

A ko-yashiki [小屋敷] is a detached tearoom erected (usually on the far side of the garden) as a free-standing building.

²⁵Sen ni shi [專にし].

Sen ni shi [專にし] means exclusively, only. In other words, the author of this essay is arguing that, from a certain point in time*, Rikyū used only rooms of this sort.

The difficulty with this assertion is that Rikyū's surviving rooms -- and certainly the Jissō-an (which was Rikyū's “small room” for most of his life†) all appear to have been roofed with small wooden shingles (in the manner that this essay ascribes to Jōō) -- apparently to give the building a feeling of lightness and impermanence (such thin pieces of wood would begin to rot, and have to be replaced every few years).

Furuta Sōshitsu (Oribe) is the one who preferred his small rooms to have deeply thatched roofs (in the manner of the farmhouses in the snowy provinces), and a delight for this style of ko-yashiki spread from him to the machi-shū who gathered around Imai Sōkyū, and so to Sen no Sōtan (whose father Shōan was at least a nominal member of Sōkyū’s group).

Rikyū, meanwhile, appears to have considered this kind of roof to look oppressive and suffocating (according to his writings).

__________

*Presumably when he embarked on his public life as a teacher of chanoyu. The oldest surviving (and apparently earliest) of his densho, the Nambō-ate no densho [南坊宛の傳書], suggests that this was around 1573.

†The two-mat rooms seem to have appeared around the time that Rikyū entered Hideyoshi's service -- perhaps because Hideyoshi objected to the daime rooms (the Jissō-an is a two-mat daime) because the sode-kabe (which was entire from floor to ceiling in Rikyū's room -- the fenestration at the bottom of the wall was introduced later, by Oribe) made it difficult for the guests to see clearly what the host was doing.

It certainly could never be argued that Rikyū’s chanoyu became more wabi after he entered Hideyoshi’s employ than before.

²⁶Wabi wo itasareshi yue [わびを致されし故].

Literally, “[because] he was doing wabi.”

²⁷Sukoshi-sukoshi yuru-shite [少〻ゆるして].

That is, on the one hand, the feeling can be rather formal; while on the other, a temae where the fukuro-dana is used can also seem quite wabi -- depending on the utensils used, and the way they are arranged.

It was for this reason that the fukuro-dana could be used in the 4.5-mat room (where its purpose was to display the utensils*), yet also tucked away into the kamae at the head of the daime in the small room† (where its purpose was to make things easier for the host‡).

__________

*This is why, in the shoin, the guests are expected to open the ji-fukuro and also inspect whatever the host may have placed therein. It is thus the complete opposite of the dōko (even though its purpose is similar) -- which exists purely for the host's convenience (the dōko must never be opened by the guests so that they may peek inside).

†The original small rooms (Jōō’s Yamazato-no-iori [山里ノ庵], shown below and on the left, and Rikyū’s Jissō-an [實相庵], below, right) were both 2-mat daime structures.

These first two rooms were followed by the ichi-jō-han [一疊半] (where the ro was moved within the kamae, making the second of the “guests’ mats” no longer necessary: this room is shown below) -- a setting with which Rikyū very quickly became disenchanted (though it remained popular with certain of the machi-shū into the early Edo period).

This prompted him to remove the sode-kabe and restore the utensil mat to a maru-jō [丸疊] (a full-sized mat) -- resulting in the 2-mat room with mukō-ro that he used for the rest of his life.

All of the other variants of the small room appeared later.

‡In other words, so that he did not have to make several trips back and forth between the temae-za and the katte.

The original sode-kabe (the "sleeve-wall" that encloses the daime-gamae) was complete from floor to ceiling, thus anything within the kamae was, for all intents and purposes, invisible to the guests. The things within the kamae were placed there simply so that the host did not have to bring them out one by one after the guests had taken their seats.

The kamae was finally superseded by the dōko (in the case of Rikyū's small rooms, perhaps beginning during the second half of 1587).

²⁸It seems that the person responsible for inserting this entry into Jōō’s text (who does not seem to have been Tachibana Jitsuzan) neglected to copy it out in full, and came back later to add what had been missed.

That is why I decided to separate this statement from the rest of the text of this section.

0 notes