#but rabbits as a motif in media? Unsettling

Text

rabbits scare me for the same reason babies scare me. not because of the harm they could do to me but because they are so small and constantly trying to die and there are so so so many ways to accidentally kill them.

but also slightly worse than babies because babies don't have razor sharp incisors that they might use to take you down with them.

#also there's something about rabbits that just unsettles me a little#not so much real rabbits those are cute until they yawn#but rabbits as a motif in media? Unsettling#it might be because back in the early youtube days I saw a video where someone did a prank with a creepy rabbit halloween mask#and it was really freaky looking and child me did Not like that#actually there was another youtube video I stumbled across around that time that was a short amateur horror film#about murderous androids with rabbit heads#so yeah actually it's entirely youtube's fault#the undead rabbit things in pinocchio actually freaked me out a bit

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Grayson Perry – very much his own man

by Lisa Jardine

In this The Long Read, first published in 2004, the distinguished historian Lisa Jardine considers the ‘extraordinary power and contemporary importance’ of Grayson Perry’s work

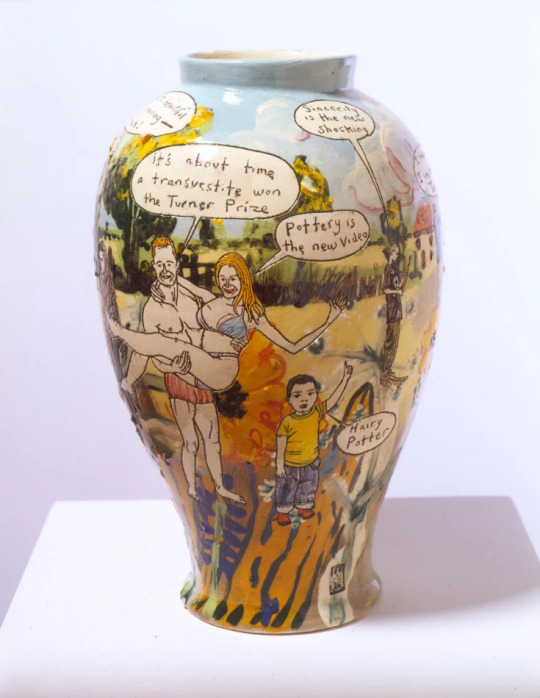

Grayson Perry’s work unsettles the contemporary art world. It is not simply that he chose to accept the Turner prize in the persona of his alter-ego ‘Claire’, dressed in the latest in his art-work ‘coming out’ frocks in mauve satin, exquisitely embroidered with rabbits, roses, hearts, and the words ‘sissy’ and ‘Claire’, and teamed with white ankle-socks and red patent-leather Mary-Jane shoes. Although, as Perry himself is quick to point out, the ‘tranny’ (which is how he refers to himself) does have a remarkable capacity to provoke anxiety. That, he explains, is some combination of disappointment and unease at the fragility of the illusion. The tranny does not try to ‘pass’ as a woman. He hovers on the brink of the absurd, all too obviously not a woman, all too clearly failing to convince, playing a part. In the street, the sidelong appreciative glance of the passer-by detects the illusion in a split second and their admiration falters. As Claire, Perry inhabits a space too close to the edge of acceptability for us – as audience – to be comfortable.

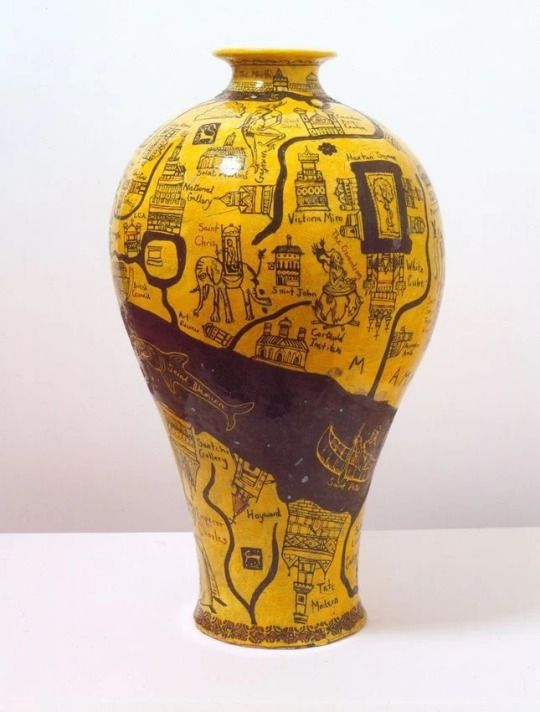

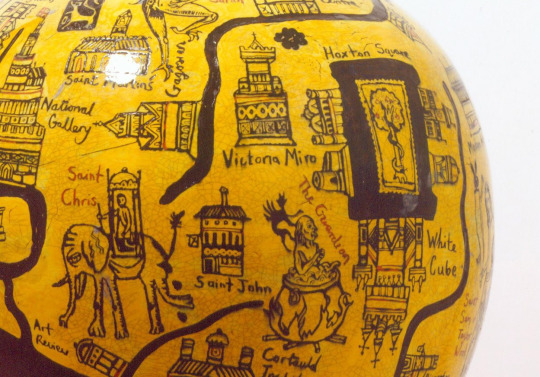

What makes the art world even more nervous than Claire is the status of Perry’s pots. Does a pot count as high art? Can an art vase move out of the world of craft, the WI, school art rooms and evening classes? The decorated pot brings the domestic, the banal everyday, into the gallery. It blurs the boundary between familiar homely clutter and the way the gallery space strives to keep us aware of the representational strangeness of the thing we are looking at – the need to scrutinise it closely if we are to understand it. Is the critical anxiety generated by Perry’s work a response to the fact that an exhibition of his ceramic pots all too-closely resembles a department store window-display of desirable consumer items set out for sale on pedestals?

Feminists have heard these kinds of questions before. Indeed, by selecting ceramics and embroidery as his preferred media Perry has chosen to inhabit that ‘second place’ – the space of inferiority – traditionally allocated to craft-based art work produced by women, over the centuries during which they were excluded from the public sphere. The repetitive painstaking nature of such ‘women’s work’ has been designated second-rate, circumscribed and limited in its ambition from the outset – or so connoisseurs and critics have maintained. Almost by definition it lacks that intrinsic élan or brio that could give rise to descriptions such as ‘serious’, ‘important’, ‘brilliant’.

Perry himself uses language that self-consciously references this art-world gesture of demotion of the feminine: ‘A vase is somewhere where we traditionally have a sensuous experience. There’s something humble about a vase – it’s not a big, showy-offy thing.’ His insistence on the artisanal nature of the work, the emphasis on repetition, the mark of the maker (Perry’s ‘W’ and an anchor mark cocks a snook at those of more conventional potters), tethers him strategically to that often disparaged tradition. As does his emphasis on a cherished repertoire of motifs, painstakingly executed in modest materials: ‘I’m interested in developing a rich vocabulary with one or two media and I think that artists who don’t do that are sacrificing part of their vocabulary, their kind of fingerprint on the work and that physical relationship to [the] work.’

In talking about his work Perry signposts the distinction between his art, with its particular kind of mesmerising beauty, and the tradition of high art. He defines as ‘sublime’ another sort of art that captures beauty with deft, minimal gestures, and is then quick to distance the work he executes from such sublimity. ‘Often the splendour of my work is in the man hours, rather than effortless’. His pots are products of painstaking endeavour, each one coiled laboriously from snakes of clay, worked gradually into a reassuringly smooth, familiar shape, with an investment of enormous amounts of attention, time and effort. ‘There’s a kind of elegant gesture of throwing [pots] which is like ballet, kind of a graceful arc – and then there’s what I do which is kind of a war of attrition. I think high culture has a big appreciation of that subtle, sublime view of beauty. Say, like Luc Tuymans, I think he’s a good example of it. Everything about the paintings depends on line, the colour relationships, the composition, the hint, the reference, the texture, everything about them is so thought about, but there’s not a lot there. And it is almost a counterpoint to my work in some ways.’

Perry chooses a different set of tactics to catch and hold the viewer’s attention. His high-gloss glazes and the liberal use he makes of gold and lustre on his surfaces draws on traditional art’s implied promise that its surface beauty will repay close scrutiny. From a distance, the seductive, shimmering beauty of the work is immediate and irrefutable, with its evocations of precious oriental art-objects, and apparent patina of age. That beauty seems to give the work an aura of authenticity, to offer a guarantee of gravitas. When the viewer does get up close, Perry rewards them with a breathtakingly rich level of detail which, in his words, ‘never lets them down’.

Perry says that he wants his work to reward and repay the viewer’s attentive inspection however close they get. Indeed, the closer they come, the more times they circle the work – which in its resolutely three-dimensional roundness can never, by its very nature, be viewed all at once – the more there is to be found and read into its detail. This is high-resolution art. Zoom in on a Grayson Perry and you access ever-finer levels of demanding detail.

With Perry’s embroidery the sensation of discovery as you move towards the work is alarming, as the apparently innocent repetitions of decorative pattern break down under scrutiny into more sinisterly meaningful components: ejaculating penises, foetuses, jet planes, hypodermic needles, swastikas. In the case of Perry’s pots, once the viewer is held by the hypnotic detail of the drawings, photographs, fragments and texts, applied to and incised on to its surface, the experience can be almost overwhelmingly intense. Perry’s pots turn out to be scary. Pots are not supposed to be extreme, they are not supposed to disturb, nor to convey thought-provoking political messages. Close-to, the viewer encounters a compilation of lurid headlines, photographic images (some family snaps, some familiar clichés), sentimental off-the-peg transfers, kitsch ornament and an obsessive vocabulary of powerful images drawn from Perry’s private fantasy. Fragmented and disjointed, directionless and in-the-round, how is one to know where the narrative begins and ends? More troublingly, who is taking responsibility for our putting together this compilation of fragments, teasing it out into our own ‘reading’ or interpretation, which undermines and disturbs our equilibrium?

It is here, with our noses up against the fantasy world of our own and his imagination, that Grayson Perry’s careful tactics for enticing us into complicity – stealth tactics for the contemporary art gallery – begin to yield a shockingly strong set of responses from us as audience to the pot’s drama. For we are all alone. Grayson Perry as artist authority-figure, called upon to assign meaning to his work, is nowhere to be found. His insistence on the subordinate, inferior stance of the ‘tranny potter’ will not allow us to look to him for any sort of masculinist or triumphalist version of the ‘meaning’ of his work. ‘It’s no good asking me. I put forward the question in the work, I don’t answer it.’

When you talk to him, Perry has an evident dread of sounding authoritative. ‘I’m tiptoeing up [on authority]. I mean I talk to my therapist about the figure of an aged but reverent orchestral conductor and I said that’s about as far as I’m going towards having authority. I’m going to be the guy who’s given authority by reverence for skill and artistry. That is the person for me, that is my kind of analogy for the sort of role that I’m tiptoeing up to – the platform of that.’

The very authenticity of the work depends, for Perry, on this refusal to take responsibility: ‘In our times, maintaining authenticity for me involves dealing with the changing role of being an artist. I think that’s an important question. How do I inhabit this role now, when my work is in demand and it can command quite high prices and I can see in other people’s eyes that they want me to take command? I want to go. It’s not my job really. It might be a job for another artist, but it’s not my job.’

It is easy to see from this why Perry should be drawn to art by ‘outsider’ artists – artists beyond the art world, who cannot be called upon to answer for the meaning or authenticity, or even the status as art, of their own work.[2] In 1979, Perry went to the Outsiders exhibition at the Hayward Gallery in London, where he encountered for the first time the work of Henry Darger, who remains his favourite artist. Entirely unrecognised in his lifetime, Darger was a reclusive loner, who lived for 43 years in a second-floor room on Chicago’s north side, and worked as a hospital janitor. When he died in 1972, he left behind an illustrated fantasy, in twelve massive volumes running to 19,000 single-spaced typed pages of legal sized paper, entitled The Story of the Vivian Girls, in what is Known as the Realms of the Unreal, of the Glandeco-Angelinian War Storm, Caused by the Child Slave Rebellion.

In Darger’s case, the artist himself is permanently absent, his artistic imprimatur forever inaccessible as part of the viewer’s transaction with the exquisitely detailed drawings and watercolour paintings which comprise the illustrations to The Story of the Vivian Girls. The gallery goer, critic or collector (Dargers sell for very large sums of money) is left alone to decide on their artistic worth. Because of the obsessive, fantasy nature of the material – its violence, its curious prurient drawings of naked girl children – the viewer cannot avoid the anxiety that they too might be sharing in some sad, solitary, obsessive fantasy. No reassuring artistic voice tells them this is not the case. An edge of doubt colours our reaction to outsider art such as Darger’s. And so it does, more deliberately, colour our response to Perry’s.

Which brings us back to disappointment. Behind Perry’s work stands a sort of sadness – the plangency of anticipated disappointment – which clings to the kinds of masturbatory fantasies he returns to again and again. Perry draws attention to this expectation of failure, of not achieving the looked-for pleasure, of loss and regret, in several modes as he seeks to specify his role as artist, and this must surely make us pay attention.

In the domain of fetish and fantasy, repetition is the endlessly deferred anticipation of a pleasure which is always less than the best that might have been. After the fantasy comes the reality – but the reality will, as every fantasist knows, always fail to live up to the fantasy. Again, as potter Grayson Perry emphasises, the disappointment comes each time the kiln door is opened – each time the pot does not quite come up to the artist’s expectations (the ideal pot in his mind’s eye). ‘That whole idea of realising fantasy and the cruelty of that, the cruelty of dealing with the disappointment. When I open the kiln I’m dealing with the fact that I’m always working with the feeling of what I hope it will be like, and then I have to deal with it coming back at me from the object when it’s finished. And you get a very sudden moment of that when you open the kiln because suddenly the feeling is into a real sensory experience. It’s like I have an idea of the atmosphere of a work and if it really works for me, it gives it back fairly closely, but very rarely.’

Then too there is Claire. Grayson Perry’s artistic agenda is already set out in his self-presentation as ‘tranny potter’, the disappointingly not-quite-perfect-enough illusion of the adorable little girl in the beautifully embroidered dress. Describing the role he sees for himself as artist, Perry says that he wants to have his hand on the shoulder of the viewer as they come to terms with his work, that he is there, quietly and submissively, having embraced his own sense of inferiority, having relinquished his status as powerful male figure in the art world. But it is Claire’s hand we find on our shoulder, warning us that after the rapture of anticipation we should be ready to settle for disappointment. That is what gives Grayson Perry’s work its extraordinary power and contemporary importance. Here is a specifically 21st century art and an emotional intensity specific to it – an emotional intensity which acknowledges the inescapable liaison between desire and disappointment, the inevitable failure of reality to fulfil our overheated consumerism –enhanced dreams.

Link to article

1 note

·

View note