#by the time i rewrote the dialogue and figured out the ending it was SEVEN FUCKING PAGES. SOLID.

Text

SORRY. JUST REALIZED I ORIGINALLY SKETCHED THE STUFF FROM THAT LAST WIP POST IN. MARCH.

GODDDD...

#I GUESS MY WRIST FUCKING UP PUT ME FURTHER BACK THAN I THOUGHT#but also like. i was JUST talking about it in chat. i have a comic about the Three Of Them that i wrote in a frenzy in FEBUARY.#by the time i rewrote the dialogue and figured out the ending it was SEVEN FUCKING PAGES. SOLID.#OF JUST SCRIPT.#I STILL HAVENT EVEN FINISHED SKETCHING IT. YOU GUYS ARE NOT SEEING THAT SHIT UNTIL 2024#sometimes an idea of them will grasp me and i will just write the script out in the middle of the night#I realistically. dont even know if you guys are gonna like my scripted stuff.#the first scripted thing i wrote was a yellow&duck comic that im STILL SKETCHING BACKGROUNDS ON#i could be really bad at writing for them. i could totally not get them at all.#but hey!#we'll see when we see I guess#BUT YEAH UH. SORRY FOR LITERALLY ALL I POST BEING WIPS NOWADAYS I AM JUST WORKING ON LIKE 5 DIFFERENT DRAWINGS AT ONCE#STILL TRYING TO GET MY SPRING STUFF DONE. AND ITS ALMOST FALL. SO :]#I JUST CARE SO MUCH ABT THOSE PUPPETS DAWG I HAVE SO MANY IDEAS FOR THEM#I HAVE!!! EVEN MORE DRAWINGS THAT I JUST HAVENT SHARED!!! bc i either made them for something real specific in the discord#or bc theyre phone doodles and i dont think theyre that great. or bc i made them just for a friend and thats like. theirs now kjdhkjdfhs#a lotta times once i finish drawing smth for a friend ill just never post it bft. so its just like. for that one thing and nothing else#ANYWAYS HAPPY 3 AM IM FORCING MYSELF TO GO TO BED#AND I STILL HAVE THE ANIMATIONS#AND THE FANART FOR LIKE 5 FICS I WANNA DO#OHHH GOD CMONNN BRO IM NEVER FINISHING ANYTHING#my postings

26 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Director’s Cut Material #9- Kurt Busiek

Kurt Busiek's acclaimed series Astro City- an anthology series that looks at the varied population of the super powered city was a long standing fixture of WildStorm's publishing history. After its initial series was published by Image Comics, it moved to Jim Lee's boutique imprint, Homage Comics. In addition to Astro City, Busiek also released many other very interesting titles through WildStorm like the Cliffhanger World War I fantasy title Arrowsmith with artist Carlos Pacheco and the ambitious crossover of the early Image Comics creations, Shattered Image which turned out to be quite the challenge.

Kurt Busiek (Writer): Originally, my thought was we were going to do Astro City on what I called, “The Sandman Plan” where Sandman early on, it was originally drawn by Sam Kieth and Sam dropped out after like six issues or so. And then they had Mike Dringenberg and they had different artists for different arcs. I thought, “That seems like a good way to do it.” I want to tell stories of all these different characters so we can get a guy who can draw great super team action for one story or we can get a guy who can do movie noir detective stuff for another story and I guy who can do a great romance story for another story and we’ll bring in guys as we need them.

What I didn’t realize is the reason that was “The Sandman Plan” was they started with Sam Kieth and then Sam left. They never intended to do it this way. It’s just how it worked out. They went on with Mike and then Mike left. They brought in other guys as needed but it was never really the intent. It’s an editorial headache to do a book like that because you need to line people up months in advance so that they’re waiting for a script while the script was being written, blah, blah, blah.

But that was my thought. I went to World Con, a Science Fiction convention in San Francisco that year. I wound up on a panel. We were talking about the comics and a guy in the audience was asking me questions. I thought, “Man, these are really specific questions. I like this guy.” After the panel, I was introduced to Brent Anderson and I thought, “Man, I’m happy to meet him.” He’s a terrific artist and since I’m planning on doing this Astro City thing, I asked him if he’d be interested in doing one of the initial six stories. He said, “Sure, I’d be happy to do it.”

I went home and thought about it and realized that after the first six issues, our intent was issues seven to twelve was going to be the Confessor story that ultimately was issues four through nine of the second series. That was a moody, dark, horror, vigilante-type story and maybe Brent would be even better at that. So I called him and asked if he’d be up to do this six-parter. He said sure.

At that time, we were negotiating with a company and they were interested in doing Astro City but they loved the idea of doing the series with rotating artists. Their thought was, “We’ll do a special or mini-series every time we can get a hot artist, we’ll do another Astro City project.” I said, “Whoa. Now, you’re making the series all about the artist. We don’t even publish it unless we get a hot guy?” I wanted to do the series ongoing and we’ll find the right guys, whether they’re hot or not. I didn’t make that deal and I thought, “You know, maybe I need a regular artist.” You know, this Brent Anderson guy, he can draw anything. He can draw super teams like Neal Adams and he can draw spooky stuff and he can draw mysteries and he can draw Kazaar-jungle action. There’s nothing that’s going to happen in the series that he can’t draw well. I called him up and asked if he’d be interested in doing the book regularly. He said, “Yes, sure.” He eased in to the series. First, doing an issue, then doing an arc and then, doing the whole thing. I kept asking him to do more. He decided he’ll do the book, I forgot whether he promised me five years or ten years. We’re coming up on 20 and he hasn’t quit on me yet so things look good on that front.

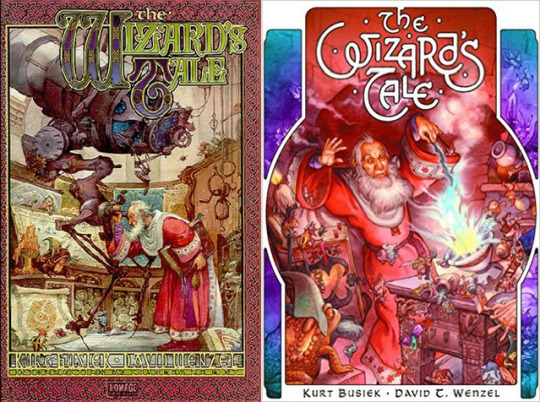

Re: The Wizard's Tale

The Wizard’s Tale was a project I did at Eclipse in the early ‘80s. It was going to be a three-issue, square-bound mini-series that we were doing because Eclipse had [done] The Hobbit adaptation and they wanted to do a Lord of the Rings adaptation. While they were negotiating for the rights to The Lord of the Rings, they needed to keep the artist Dave Wenzel busy. I was asked to maybe step in and do a project with Dave while they were working out these rights. Dave had these characters and I had a story idea. They kind of meshed together and we were able to take this one thing that he wanted to do for years and this other thing that I wanted to do for years and braid it together into the same story.

We did that and three weeks before the first issue was supposed to come out, Eclipse went bankrupt. The book never came out through Eclipse. When I brought Astro City over to WildStorm, I said, “I had this other project too, The Wizard’s Tale.” At the time, the problem was that we had the rights back to the material but we didn’t have the art back, because the last two issues worth of art had been sent to Hong Kong for color separation. This was way back in the primitive days, this was color separation where you actually would ship full painted art to a place in Hong Kong and they’d do the scanning and the separation. Because Eclipse went bankrupt, the color separator in Hong Kong didn’t get paid for everything. They wanted their money so they didn’t want to return the art they had. We had kind of a nightmare going, “We can’t pay you for color separation because we’re not the publisher. You have to deal with the bankruptcy courts for that. But Eclipse doesn’t own this art, Dave Wenzel owns this art and you need to give it back to him.”

Finally, I think what we did was this was going to be a co-publication between Eclipse and Harper-Collins and Eclipse didn’t exist anymore but Harper-Collins did. Dave visited Harper-Collins in New York and I was at a convention in London. I visited Harper-Collins in London which is where the editor who’s going to be working on the line was anyway. Eventually, we got Harper-Collins to tell the color separator, “Give them back their art.” We got the art back and I just told Jim and Scott Dunbier and John Nee, “I had this other project,” and I sent them some of the art and they said, “Yes, we want to publish that.” It took awhile because there were color separation issues but not the same ones. But eventually, we published that as a graphic novel though WildStorm. I think Eclipse had gotten the first issue lettered by somebody but the lettering had long been lost. We started over again and I rewrote the script a little.

Instead of doing it as a three-issue mini-series, we did it as a graphic novel. It went through a hardcover printing and two soft cover printings at WildStorm before they figured that it had sold as much as it was going to and eventually, we got the rights to it back. That currently is in print from IDW with Scott Dunbier again.

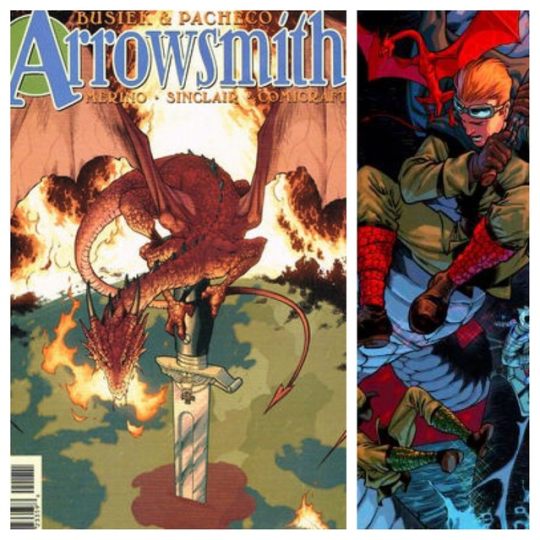

Re: Arrowsmith

Carlos and I did Avengers Forever together. Carlos had specifically requested, when he was renewing his Marvel contract, “I want to do an Avengers project and I want Kurt Busiek to write it,” which was very flattering to me because Carlos was a fantastic artist. We had a very good time working together and around the time we were finishing Avengers Forever, I was involved with Mark Waid, Karl Kesel and other people in starting up Gorilla Comics, which ultimately published through Image.

I talked to Carlos about being one of the Gorilla partners and we talked through ideas for what we could do for a book for Gorilla. We came up with Arrowsmith. My thinking had been that Carlos did such a good job, he gave the future technology of Kang the Conqueror [to] look so specific, building a culturally-cohesive world and giving him another world to design where it could be full of interesting weaponry and vehicle design, it would be a great way to make use of his talent. Doing this alternate world, World War I with fantasy grew out of that.

In the end, Carlos wasn’t able to make the jump to Gorilla because we were all essentially working without the financial security net of Marvel or DC and Carlos needed that. We still wanted to do Arrowsmith [and] a few years later, Carlos was invited to do a book for Cliffhanger which was one of the other WildStorm imprints. Carlos said, “Oh, I could do this Arrowsmith that Kurt and I talked about for Gorilla.” He called me up and said, “Do you want to do this?” I said, “You betcha.”

We made the deal with Cliffhanger and did a six-issue Arrowsmith series and that, we did directly with Scott [Dunbier]. It’s funny, I sometimes poke fun at Scott for it saying, “As far as I can tell, he never even read the plot.” He’ll glare at me and say, “Of course I read the plot. There’s nothing wrong with them.” He’d bug me about schedules and he talked to Carlos when things are coming in and things like that. I’d write up a plot and I send it to Scott and he’d send it to Carlos. I wouldn’t hear back from him. Carlos would draw the pages and I’d write the dialogue for pages and send it in. I wouldn’t hear back from Scott. The point at which I’d hear back from Scott was when we were going over final proofs, proofreading the lettering and making sure that the colors were right and text was right and things like that. Scott comes out of an original art background. He was an original art dealer. I think that he’s extremely focused on, “I want this book to print well and I want it to look great and I want to show off the beautiful art.”

But in terms of what the story was, I don’t know. As far as I could tell, I was sending him the plot and he was sending them to Carlos like it didn’t matter. Now, he tells me, of course he read it and it was fine but I didn’t get any edits from him. I have no evidence that he read it. He swears to me that he has. I will take him at his word because he’s a fine man [laughs].

Re: Shattered Image

It was a nightmare. I honestly don’t remember a lot of the details so if somebody else says, “Kurt’s wrong about that,” take them at their word. My memory of it is Image wanted to do this crossover and I think the starting point for it was Jim Valentino. Jim wanted to do something that crossed everybody over and involved everybody. Or else, Image wanted to do it and Jim was tasked to make it happen. Jim offered it to me because I’d been writing Shadowhawk for him and I was the guy who had written more stuff. There were all different guys who’d written for Image but they generally wrote for one studio or another. I’d written at least something for most of them.

Jim thought I’d be a good choice because I worked with him and I’d been talking about a project with Eric [Stephensen], even though it had never come up, and I’d worked for Marc [Silvestri] and I’d worked for Jim Lee and I’d worked for Rob. At the time I was busy, I didn’t have much time so I think that’s why we brought in Barbara Kesel as co-writer. I knew Barbara. Barbara lived locally [and] was looking for writing work and I thought, “This is something we can do together easily and have fun with it.”

We co-plotted everything together and I did the first half of dialogue on issues one and three and she did two and four or the other way around. Then, we worked at each other’s stuff. But what I mostly remember is that we were doing this big crossover and during the middle of it, [Marc Silvestri's studio] Top Cow quit Image and we had to write all the Top Cow characters out. And then Extreme, Rob Liefeld’s group, they quit Image or got kicked out of Image so we had to write all those characters out. And then, Top Cow came back because part of the thing that Top Cow was angry about was a dispute with Rob and so when Rob got kicked out of Image, that solved the problem and Marc was willing to come back. As a result, I think in issue three, all the Top Cow characters disappear from the world. We’d gotten an okay that we could still publish issue three as long as we wrote them out. In issue four, we had to get rid of all the Youngblood characters. And then we got the word that the Top Cow characters were coming back. I may be remembering this wrong, but I think that on the last page of the last issue, there’s a long shot of planet Earth from space and a word balloon was coming from the planet saying, “We’re back.”

Literally, that’s how we had the Top Cow characters reappear because we were messing around the timelines being broken and shattered and things like that. I’m sure that the story reads like a mess because the original place we were going with it was so derailed by partners leaving Image and coming back in and so forth so we were just hanging on by our fingernails going, “Okay, we've got to do this and we've got three pages left. There are three pages that haven’t been penciled so we’ve got that much room to make all the Extreme characters go away and all the Top Cow characters come back.”

We can re-dialogue the earlier stuff but we can’t have it redrawn because there’s not time [laughs]. That’s how that happened.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

6 Lessons Learned from a Year of 101 Rejections

By Natalie D-Napoleon

Earlier this year I came across an article by Kim Liao in which she explained “Why You Should Aim For 100 Rejections A Year.” As soon as I finished reading the piece I went to the folder in my email marked “Writing Submissions 2017” and for the first time in my life, I began to count my rejections rather than counting my acceptances. I had effortlessly amassed 53 rejections. I punched my fist in the air and whooped out loud. It was June and I was already halfway to 100 rejections for the year.

Writer���s Market 2018: The Most Trusted Guide to Getting Published

I am the sensitive type (of course, I’m a writer): I weep openly when listening to sad love songs or during Claire and Jamie’s various reunifications on Outlander, and I have cried in the past on my friend’s and husband’s shoulder when my writing has been rejected. However, before Kim Liao’s article, another woman had sent me on the journey of beginning to accept that rejection was less about failure and more about getting closer to your goals. In 2015, I attended the first BinderCon conference in L.A. BinderCon began as a “secret” Facebook group of women writers sharing contacts and information and grew into a movement and conference which supports women and gender variant writers.

At BinderCon 2015, Katie Orenstein, founder of The OpEd Project, spoke about the lack of representation of women in the media and the reasons why. As a former journalist and foreign correspondent, she had a perspective on being rejected that I could not fathom at the time. Orenstein opened my eyes to one impressive fact—that women submit their work less than men. She had the statistics to prove it and the acceptances and consequent higher representation of men in the media. In one generalized conclusion: When women and people of color get rejected, we take it personally. When white men’s work is rejected, they don’t take it as a measure of the worth of their work—they decide it simply needs to find the right home elsewhere.

Orenstein says that the dearth of women’s voices in the media, “has affected the quality of our nation’s conversation, the way research is conducted, how stories are reported, and how history plays out—and indeed, what we think history is. As it turns out, the most crucial factor in determining history is more often not the distinction between what is fact and what is fiction, but who tells the story.”

Orenstein’s talk put a fire in my belly. I had an aim now that was both personal and political, to start by not taking writing rejections personally, and to submit more often because that’s what had worked, most likely for centuries of successful male writers. I didn’t aim for 100 rejections in that year; however, I had begun a master’s degree in writing, and the idea was placed in my back pocket for when I had produced the work that needed to be put out into the world. The formula seemed so simple: Submit, submit, submit, submit, and don’t take rejection personally.

Checking that “Writing Submissions 2017” folder again as I neared the end of December 2017, I counted 100 rejections—and one written rejection in a pile of papers on my desk from The Sun—took me to 101! While walking the path that Kim Liao and Katie Orenstein put me on, I have learnt a few lessons:

1. Have a body of work to submit.

In the past when I had submitted work. I didn’t have a body of work behind me to make submitting worth my while—just a handful of poems, a new short story every year. From 2014 to 2016 I completed my degree online. With a four-year-old and a part-time job as a writing tutor, I didn’t have much time to do anything other than produce creative writing. I was ferocious and voracious; I wrote and wrote and re-wrote and didn’t stop to think for a moment about what I would do with the work. I simply enjoyed the process of creating after taking a break for several years to be a mom and pursue the life of a singer-songwriter. What this time gave me was a significant body of work to begin dipping in to in order to begin submitting when the time was right. By the time I completed my degree, I had a complete poetry collection and several creative nonfiction essays ready to submit.

Online Course: Fearless Writing with Bill Kenower

2. Pitch your submissions like a freelance journalist pitches stories.

My husband is a freelance journalist, so when I began submitting and expressing my frustration when I was rejected, his first question to me was Why don’t you try submitting like journalists do? “Research the publication, the editors, the judges, and pitch the work you think will resonate specifically with that publication or judge,” he advised.

I had read the worn “read our publication before you submit,” but I figured that advice was for everyone else, not me. Despite my reservations, I started to heed his and journal editors’ advice, I began to read publications and pitch my work accordingly. This meant researching editors, then finding examples of their work online and reading them. I can say that a good portion of my acceptances—and positive rejections—were the result of taking the time to research and read before I submitted work. The added bonus: I discovered new writers, poetry and creative nonfiction writing that I both enjoyed and could learn from in order to improve my own work.

As a part of this process, I subscribed to each journal’s mailing list. I now regularly go to my email inbox and read these mailings, which often leads to submitting work when themes are called for, or reminds me of reading periods and submission deadlines.

3. Rewrite to meet the word count, and learn to edit your work.

Continuing to think like a freelancer, when I found competitions I wanted to enter, I rewrote work to meet the word count or cut stanzas out of poems to meet the line count. Through this process I became a better editor of my own work. I removed a whole stanza from one poem that placed me second in a competition, and I now prefer the edited version.

I came to discover what author Katherine Paterson says: “I love revisions. … We can’t go back and revise our lives, but being allowed to go back and revise what we have written comes closest.”

Part of this process also meant finding good, trustworthy readers of my work who would give me feedback on what was working and what was not in my writing. In the past I took little time to reflect on my own work, or to find readers. Often, knowing that I had a reader about to peruse my work with a critical eye made me edit more ruthlessly before forwarding my work to them. I learned to ask my readers for specific feedback—e.g., “What do you think of the dialogue on page two of the story?” This helped me identify the weak areas in my own work, especially when readers confirmed my own judgement.

The rejection process also allows you to get to know your stronger and weaker work through the self-reflective process of editing, getting reader feedback, and occasional editorial feedback. As Paul Martin writes in Writer’s Little Instruction Book – Getting Published, “Every rejection … adds to your knowledge about the right market for your work.”

4. IRL connections matter.

No art is created in a vacuum, and no art exists without community. Often writers find community online; however, very few of my online connections have been made without some seven-degrees-of-Kevin-Bacon real life connection. When I began my master’s degree I joined two different local in-person writing groups, began attending local poetry readings and book launches, and through this process I met local writers and publishers.

Eventually these relationships—and I’d like to think the quality of my work—led to getting a poem published in an ekphrastic poetry collection by a local publisher. A friend suggested I submit a memoir piece to a local reading series, and although I had a cold and hacking cough at the time, I thought about my 100 rejections, soldiered on and made a recording. I was accepted to the series, got to read to a full room of attentive listeners, and was coached by a drama teacher on how to read my work aloud—another valuable lesson—all the while connecting with a local writing community I could lean on in the process.

5. Celebrate encouraging feedback.

As an editor told Liao in (according to her article), “The thrill of an acceptance eventually wears off, but the quiet solidarity of an encouraging rejection lasts forever.” The few personal notes I received in 2017 added fuel to the fire, which kept me submitting. When a prominent journal in Australia rejected two poems they wrote, “We enjoyed the intense, vertiginous imagery in these poems,” and then urged me to submit more work in the future. Encouraging rejections let you know your writing is on track (and apparently gives some people vertigo), and that someone out there is carefully considering and paying attention to your work.

The added bonus is that once you know the editors like your work, if you continue to submit to that journal they should: a) remember your name, and b) eventually accept a piece. Getting to know the body of work of an emerging writer is what often gives editors an “in” to understanding your unique point of view. After I had a poem accepted for publication in Australian Poetry Journal, I realized I recognized the editor’s name, and when I reviewed my submissions I found out that I’d sent samples of my work to other journals she edited. Maybe she recognized my name, or maybe once she read the work one more time it “clicked.”

6. Set aside regular time to submit, review and rewrite your work.

Because I was inspired by Liao’s article to continue submitting, I began to set aside time each week to submit. However, this didn’t mean I began submitting blindly. I would carefully study the newsletters of journals, do Google searches, read the Submittable weekly mailer and search the site, the Poets and Writers newsletter, and save competitions that arose on Facebook. Then I would take the time to read the journal I wanted to submit to and decide if my work was appropriate or needed to be rewritten, or if I needed to review my own body of work to find something that may fit a theme call-out. By doing this for an hour or two, two or three days a week, I built up to 101 rejections.

I also learnt during the process that I had underestimated some of my own work. My experimental erasure poetry was being published extensively, and I found that what Orenstein had suggested was true: more rejection builds resilience and an ability to brush it off. Most of all, I realized the truth of what Zora Sanders, the former editor of Australian journal Meanjin Quarterly, said: For women to bring our work to the attention of editors we need “to take more risks.”

This led me to the greatest lesson of all: How to use rejection to review my work and improve my writing.

And the result of my year of 101 rejections? I won second place for my poem “First Blood” and had another poem commended in a poetry competition judged by the international editor of the Kenyon Review; I made two competition shortlists with a creative nonfiction memoir piece, “Crossing,” and then the same story was accepted by a major Australia literary journal for publication; I had four erasure poems published online and another accepted in Australian Poetry Journal; I read a memoir piece at a local reading series to a sold-out room, and finally, an ekphrastic poem was published in a collection by Gunpowder Press. That’s 11 acceptances for 101 rejections, if anyone is counting.

This year, I’m prepared to aim for 102 rejections with glee, while I quietly place a few more cracks in the literary glass ceiling.

Natalie D-Napoleon is a writer, singer-songwriter and educator from Fremantle, Australia who now lives in California. She has an MA in Writing from Swinburne University and currently works as a Coordinator at a Writing Center in a California city college. Her work has appeared in Entropy, The Found Poetry Review, LA Yoga Magazine and the Santa Barbara News-Press. Recently, her story “Crossing” made the finalists’ list for the Penelope Niven Prize in Creative Nonfiction, and her poem “First Blood” placed second in the 2017 KSP Poetry Awards judged by John Kinsella.

Twitter and Instagram: @nataliednapo

Blog: http://nataliednapoleonwordplay.blogspot.com/

The post 6 Lessons Learned from a Year of 101 Rejections appeared first on WritersDigest.com.

from Writing Editor Blogs – WritersDigest.com http://www.writersdigest.com/editor-blogs/questions-and-quandaries/publishing/6-lessons-learned-year-101-rejections

0 notes