Quote

The existence of good bad literature—the fact that one can be amused or excited or even moved by a book that one’s intellect simply refuses to take seriously—is a reminder that art is not the same thing as cerebration.

George Orwell

(via theperksofbeingabookseller)

82 notes

·

View notes

Text

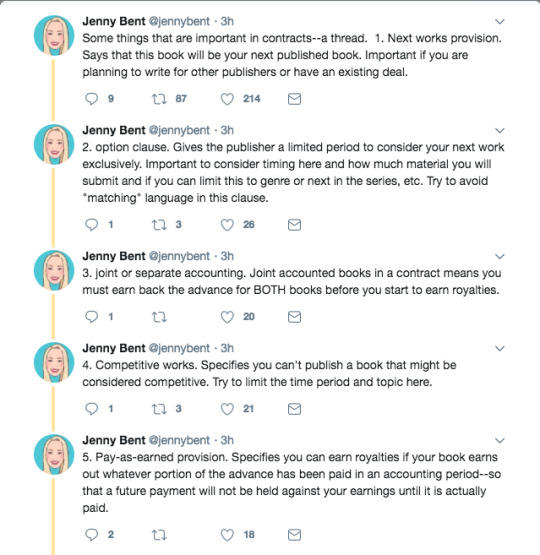

some highlights from my writing seminar with honestly one of my favourite authors of all time who shall remain nameless bc i dont want her to know i was spilling her secrets online

The first trick is to detach yourself from your idea. You don’t have just one novel inside you, and it’s not a big deal if you don’t finish this novel.

She was skeptical of the common advice “just write!!1!” - she talked about how long ideas for her most popular novels were marinating inside her before she properly wrote them

As a continuation of that, she was a big believer in knowing what you want to write before you write it. Not what you’re going to write, what you want to write.

The first thing she decides about a novel is what the mood is going to be, and this informs every other decision (e.g. the mood for Shiver was bittersweet)

Ideas should be personal, specific, exciting and they should exclude secondary sources. A personal idea isn’t necessarily autobiographical (which should be avoided), but it speaks to your emotional truth.

She said she had been read Ronsey fanfiction and she couldn’t view her car in the same way since.

Story is the thing that seems most important to reader but is most changeable to the author - story is subservient to your mood and your message. Change what you like in the plot as long as your book retains its sense of self.

Story is conflict, exploration and change. A good story has active tension -the characters want something, instead of just wanting something not to happen (e.g. wanting to kill an enemy instead of simply defending a stronghold against an enemy)

A story needs to have a concrete end, something to be done.

Satisfaction is important - deliver what you promise to the reader. The other shoe has to drop. Ronan Lynch doesn’t ever talk about his feelings, so its rewarding when he does.

Earn your emotional moments (she threw shade at Fantastic Beasts lmao)

Forcing a character to be passive is dissatisfying to the reader.

Characters are products of their environments, consistent/predictable, nuanced and specific, moving the plot, and subservient to other story elements.

She always starts with tropes for ensemble casts like sitcoms. Helpful for building good character dynamics.

Write scenes with characters saying explicitly what they’re thinking and then go back and make them talk like real people in the edit.

An action can also prove what they’re thinking, instead of making them say it or another character guess it (e.g. Ronan punching a wall).

Move the reader’s emotional furniture around without them noticing.

All her books follow the three act structure. Established normal -> inciting incident -> character makes an Active Decision -> fun and games -> escalation -> darkest moment -> climax.

Promise what you’re going to do in the first five pages.

Read your book out loud. Record yourself reading it.

If you have writer’s block, it’s because you’ve stopped writing the book you want to write. She likes to delete everything she’s written until she gets back to a point where she knew she was writing what she wanted to write, and then carrying on from there.

22K notes

·

View notes

Text

Is it right that I'm nearly all of these writers?

pick-me-ups for writers

for the self-conscious beginner: No one makes great things until the world intimately knows their mediocrity. Don’t think of your writing as terrible; think of it as preparing to contribute something great.

for the self-conscious late bloomer: Look at old writing as how far you’ve come. You can’t get to where you are today without covering all that past ground. For that, be proud.

for the perfectionist: Think about how much you complain about things you love—the mistakes and retcons in all your favorite series—and how you still love them anyway. Give yourself that same space.

for the realist: There will be people who hate your story even if it’s considered a classic. But there will be people who love your story, even if it is strange and unpopular.

for the fanfic writer: Your work isn’t lesser for not following canon. When you write, you’ve created a new work on its own. It can be, but does not have to be, limited by the source material. Canon is not the end-all, be-all.

for the writer’s blocked: It doesn’t need to be perfect. Sometimes you have to move on and commit a few writing sins if it means you can create better things out of it.

for the lost: You started writing for a reason; remember that reason. It’s ok to move on. You are more than your writing. It will be here if you want to come back.

98K notes

·

View notes

Text

It's coming for you

The Emotions of Horror

In order to successfully write horror, you must first understand fear. Fortunately, fear is a universal experience, and likely something you have intimate first-hand knowledge of - the key is learning to harness your fears so they can be translated for the page.

First, recognize that different techniques and approaches will work better in different media. What works well in a horror movie may not translate well to a written story, and vice versa. Understanding your medium and your goals will help you work to the strengths of the medium and provide the most effective approach.

Second, remember that horror, perhaps more than any other genre, is at its core interactive. Even a linear story told through writing or visual cues invites participation from the reader: You need them to engage so that they will bring their own fears to the table. Simply seeing characters interact with frightening things isn’t enough; you need to invoke fear in the reader by inviting them to experience the things that you describe. That’s something I’ll delve into in greater detail in a later post, but for now, keep it in the back of your mind.

Two Main Types of Horror

There are two primary types of horror reactions you can create in a reader: Visceral horror, and cerebral horror.

Visceral horror is felt in the gut. It preys upon the lizard brain and taps into basic primal fears. Visceral emotions include disgust and shock. It is most effective in visual media, where a viewer sees images and responds to them before their brain has a chance to process them, but you can still invoke these feelings through the careful use of description. More on that in a minute.

Cerebral horror is felt in the brain. It’s the type of horror that you think about hours or days or years later, the kind of disturbing ideas that implant themselves in there and become more frightening the more you consider them. These are rooted in anxiety rather than the primal lizard brain. Cerebral horror includes fridge horror and dread. A tightly crafted story will beat a movie every time when it comes to cerebral horror, because written media is more intimate. Use that to your advantage.

The Emotions of Horror Stories

Let’s talk in a little more detail about the emotions that you should work to create in your reader when crafting a horror story. In order of most-difficult to most-natural for the written medium, try experimenting with:

Shock: Films and video games can fall back on the “jump scare,” a tactic wherein you rapidly break suspense with a sudden visual cue, almost always accompanied by a loud noise. If you need an example for some reason, turn to the nearest Five Nights At Freddy’s game.

Jump scares work by temporarily startling the viewer, short-circuiting their conscious brains and tapping directly into their oldest and most primal reflex. Newborns startle when they are exposed to too much sensory input - it’s literally their first line of defense. When you jerk, scream, or flail, you are tapping in to the newborn infant part of your brain.

Can you do a jump scare in a novel? Probably not. For one, there is no sound, and sound is extremely important to a successful jump scare. For another, reading involves conscious interaction with text; you can’t really bypass their thought processes enough to invoke a jump scare response (except for the occasionally really susceptible reader).

But you can still shock them, and that’s just as good.

Shock occurs when a reader is totally blind-sided by new information. They think they know what’s going on, but in reality, the truth is something unexpected (and perhaps far more sinister). They think a certain character is safe, only for them to be suddenly and brutally murdered. They think they’ve solved the puzzle, but the rabbit hole actually goes much deeper. I’ll talk about shock in greater length in another post, because it is so difficult to do well and requires a lot more attention.

Disgust: Gore and “splatterpunk” relies on the visceral response of disgust. We are naturally repulsed by certain things, and that too may be hardwired into our DNA (although it’s also partly based on nurture and cultural factors). But basically, disgust exists to keep us away from things that may hurt us, like diseased things.

Triggering disgust in your reader will mostly fall to writing effective descriptions. Word choice matters a lot when it comes to writing gore. Some words just feel gross (think “moist”), and some invoke really icky mental images. I’ll write a whole thing on tricks to writing gore at a future point, but for now a word of caution: Horror cannot rely on gross-out scenes alone. You might invoke a kind of sick fascination in the reader, but you won’t really scare them.

Dread: Suspense and dread are vital ingredients to horror in any medium. They work by drawing the reader into the story, enticing them to think ahead - but stripping away their certainty about what will happen. A really good story will alternate between shock and dread, building up tension before twisting the narrative in an unexpected direction.

I wrote a little bit about invoking dread here, and I’ll delve into the topic at greater length later. But for now, remember: Suspense lies in giving the reader the pieces to a puzzle, but withholding context. It forces the reader to think ahead, to try and make sense of what they’re seeing, and to imagine terrible conclusions. It encourages the reader to think “what if…?” or “something terrible is going to happen but when? how? what?”

This is something you can only do well if the reader is invested in the characters and truly cares about them. Fortunately, because writing is so intimate, it’s easier to delve into a character’s mind and forge a strong connection between them and the reader.

Fridge horror: Fridge horror is basically when something becomes creepier or more disturbing the longer you think about it. It’s when the implications of something are more horrifying than what you see on the surface. It’s the part of the story the reader takes with them, the part that makes them question their own beliefs or world-view or even reality.

It is a cerebral horror, and it’s the thing that written stories can really excel at. I will - you guessed it - write a whole post on the topic in the near future, but until then, realize that fridge horror relies in part on logic (”oh god, this means THAT!”) and part empathy (”can you imagine what it must be like….?”)

The best fridge horror moments will be pulled from your own personal experiences and fears. While anyone can tap into primal fears (the dark, the unknown, disgusting things), fridge horror is often deeply personal and oddly specific. It’s raising a question and leading the reader to think “Oh god, I never thought of that, but it is terrible.”

I’ve rambled on a long time now, and I have many things to come back to and explain in more detail - but for now, hopefully this gives you something to think about! Until next time, stay scared :)

8K notes

·

View notes

Text

4 Things to Focus on in Your First Rewrite

Every year, we’re lucky to have great sponsors for our nonprofit events. Reedsy, a 2018 “Now What?” sponsor, is a user-friendly site that helps authors find editors, designers and publicists. Today, Reedsy staff writer Martin Cavannagh shares his top tips on how to approach your first novel edits:

Everybody talks about how hard it is to finish a first draft—as if to suggest everything that comes after that is a joyride. But in reality, the work has only begun.

Many advice posts will offer a laundry list of novel revision tactics: Show, don’t tell! Hone your dialogue! Get rid of unnecessary adjectives! These are all valuable tips, but your first rewrite must focus on basic storytelling. In this post, we’ll look at four things you should address in your first revision.

1. Uncover any hidden motifs and themes.

Keep reading

1K notes

·

View notes

Link

Mia Botha: ‘As writers, we should know more about our characters than we know about ourselves. We should know instinctively how they will react and what they will do.

We also need to know how they act and react on a sexual level. Sometimes, we are too embarrassed to write a sex scene.

Writing a sex scene is like jumping into a freezing pool. You stand on the edge for a moment, thinking about the wisdom of this decision before you jump. Once you hit the water your heart feels like it is going to seize and then it takes a moment for your brain to register that you are not going to die. Your limbs start moving and you realise this isn’t all bad.’

So, if you’re brave enough to try, read my series on Writing Sex Scenes:

390 notes

·

View notes

Text

Conveying Worldbuilding Without Exposition!

(As requested by both an anon and @my-words-are-light)

One of the hardest parts of writing speculative fiction is presenting readers with a world that’s interesting and different from our own in a way that’s both immersive and understandable at the same time.

Thankfully, there are a few techniques that can help you present worldbuilding information to your readers in a natural way, as well as many tricks to tweaking the presentation until it’s just right.

Four basic techniques:

1. The ignorant character.

By introducing a character who doesn’t know about the aspects of the world building you’re trying to convey, you can let the ignorant character voice the questions the reader naturally wants to ask. This is commonly seen in cases where the protagonist is brought into a new world, society, organization, etc, but non-PoV character put under the same circumstances can be equally useful.

It works best when the inclusion of the ignorant character feels natural. They must have a purpose in the story outside of simply asking questions.

2. Conflicting opinions.

A fantastic way to convey detailed world building concepts is to have characters with conflicting viewpoints discuss or argue about them. Unless you’re working with a brainwashed society, every character should hold their own set of religious, political, and social beliefs.

Examples of this kind of dialogue:

Keep reading

19K notes

·

View notes

Note

Screenplay question: How do you avoid a predictable twist?

I’d say this is less a screenplay question and more a story question. I tend to park my twists around the midpoint and the end. Why two?

To that I’d reply, “Why not two?”

Okay. So let’s do a little exercise.

First, why do you feel it’s predictable? Make a list of reasons and get those out of your head.

Now, can you group those reasons into categories like characters, plot/structure, and general self-loathing, do it, because you might notice some trends.

Once you’ve got those trends noted, that’s when you can do one of my favorite things as a writer: screw with people’s expectations!

Structural stuff, I think, is the hardest. Movies in general are formulaic to the point that it makes me want to vomit, but they’re so formulaic because it’s works, so you walk a delicate balance. Too far in the other direction and people won’t understand or be able to follow along, and that’s no good either. Regardless, play with the pacing. Try moving up some events or drawing them out. Worst thing that happens is you try some stuff out and it doesn’t work.

Pro Tip: Write your plot points on index cards and rearrange till your heart’s content. Snap a picture or something, then rearrange it again. Repeat.

Sometimes you have a great structure, but the characters are taking the shine off it. Do you have any Mary Sue/Gary Stu’s running around being the character equivalent of Wonder Bread? Ditch ‘em or re-work them. I can’t tell you how many great plots–and twists!– I’ve seen ruined by shit characters. One thing that has helped me is to always know the character’s motivations and to think in terms of verbs. It’ll make your life easier and make your actors happy.

Also, don’t forget to think about the overall environment in the scene, too. You can contrast or highly things effectively with the surroundings as well, and not enough writers do it.

Hope this helps,

Graphei

361 notes

·

View notes

Text

aww nasa has a page for space technology terms you can use in science fiction

nerds

198K notes

·

View notes

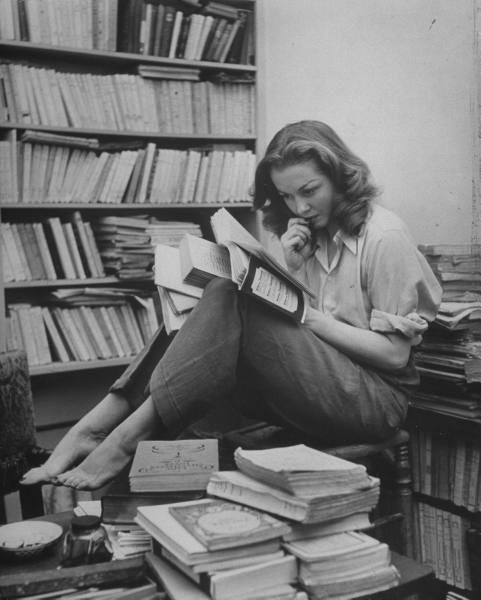

Photo

Sylvia Plath. 1932-1963

“I can never read all the books I want; I can never be all the people I want and live all the lives I want. I can never train myself in all the skills I want. And why do I want? I want to live and feel all the shades, tones and variations of mental and physical experience possible in life. And I am horribly limited.”

99K notes

·

View notes

Text

Your Character’s Personality

Personality is the most important thing about your character.

So, whenever I see character sheets, most people just put a little paragraph for that section. If you’re struggling and don’t know what your character should say or do, what decisions they should make, I guarantee you that this is the problem.

You know your character’s name, age, race, sexuality, height, weight, eye color, hair color, their parents’ and siblings’ names. But these are not the things that truly matter about them.

Traits:

pick traits that don’t necessarily go together. For example, someone who is controlling, aggressive and vain can also be generous, sensitive and soft-spoken. Characters need to have at least one flaw that really impacts how they interact with others. Positive traits can work as flaws, too. It is advised that you pick at least ten traits

people are complex, full of contradictions, and please forgive me if this makes anyone uncomfortable, but even bullies can be “nice” people. Anyone can be a “bad” person, even someone who is polite, kind, helpful or timid can also be narcissistic, annoying, inconsiderate and a liar. People are not just “evil” or “good”

Beliefs:

ideas or thoughts that your character has or thinks about the world, society, others or themselves, even without proof or evidence, or which may or may not be true. Beliefs can contradict their values, motives, self-image, etc. For example, the belief that they are an awesome and responsible person when their traits are lazy, irresponsible and shallow. Their self-image and any beliefs they have about themselves may or may not be similar/the same. They might have a poor self-image, but still believe they’re better than everybody else

Values:

what your character thinks is important. Usually influenced by beliefs, their self-image, their history, etc. Some values may contradict their beliefs, wants, traits, or even other values. For example, your character may value being respect, but one of their traits is disrespectful. It is advised you list at least two values, and know which one they value more. For example, your character values justice and family. Their sister tells them she just stole $200 from her teacher’s wallet. Do they tell on her, or do they let her keep the money: justice, or family? Either way, your character probably has some negative feelings, guilt, anger, etc., over betraying their other value

Motives:

what your character wants. It can be abstract or something tangible. For example, wanting to be adored or wanting that job to pay for their father’s medication. Motives can contradict their beliefs, traits, values, behavior, or even other motives. For example, your character may want to be a good person, but their traits are selfish, manipulative, and narcissistic. Motives can be long term or short term. Everyone has wants, whether they realize it or not. You can write “they don’t know what they want,” but you should know. It is advised that you list at least one abstract want

Recurring Feelings:

feelings that they have throughout most of their life. If you put them down as a trait, it is likely they are also recurring feelings. For example, depressed, lonely, happy, etc.

Self Image:

what the character thinks of themselves: their self-esteem. Some character are proud of themselves, others are ashamed of themselves, etc. They may think they are not good enough, or think they are the smartest person in the world. Their self-image can contradict their beliefs, traits, values, behavior, motives, etc. For example, if their self-image is poor, they can still be a cheerful or optimistic person. If they have a positive self-image, they can still be a depressed or negative person. How they picture themselves may or may not be true: maybe they think they’re a horrible person, when they are, in fact, very considerate, helpful, kind, generous, patient, etc. They still have flaws, but flaws don’t necessarily make you a terrible person

Behavior:

how the character’s traits, values, beliefs, self-image, etc., are outwardly displayed: how they act. For example, two characters may have the trait “angry” but they all probably express it differently. One character may be quiet and want to be left alone when they are angry, the other could become verbally aggressive. If your character is a liar, do they pause before lying, or do they suddenly speak very carefully when they normally don’t? Someone who is inconsiderate may have issues with boundaries or eat the last piece of pizza in the fridge when they knew it wasn’t theirs. Behavior is extremely important and it is advised you think long and hard about your character’s actions and what exactly it shows about them

Demeanor:

their general mood and disposition. Maybe they’re usually quiet, cheerful, moody, or irritable, etc.

Posture:

a secondary part of your character’s personality: not as important as everything else. It is advised you fill this out after. Posture is how the character carries themselves. For example, perhaps they swing their arms and keep their shoulders back while they walk, which seems to be the posture of a confident person, so when they sit, their legs are probably open. Another character may slump and have their arms folded when they’re sitting, and when they’re walking, perhaps they drag their feet and look at the ground

Speech Pattern:

a secondary part of your character’s personality: not as important as everything else. It is advised you fill this out after. Speech patterns can be words that your character uses frequently, if they speak clearly, what sort of grammar they use, if they have a wide vocabulary, a small vocabulary, if it’s sophisticated, crude, stammering, repeating themselves, etc. I personally don’t have a very wide vocabulary, if you could tell

Hobbies:

a secondary part of your character’s personality: not as important as everything else. It is advised you fill this out after. Hobbies can include things like drawing, writing, playing an instrument, collecting rocks, collecting tea cups, etc.

Quirks:

a secondary part of your character’s personality, not as important as everything else. It is advised you fill this out after. Quirks are behaviors that are unique to your character. For example, I personally always put my socks on inside out and check the ceiling for spiders a few times a day

Likes:

a secondary part of your character’s personality, not as important as everything else. It is advised you fill this out after. Likes and dislikes are usually connected to the rest of their personality, but not necessarily. For example, if your character likes to do other people’s homework, maybe it’s because they want to be appreciated

Dislikes:

a secondary part of your character’s personality, not as important as everything else. It is advised you fill this out after. Likes and dislikes can also contradict the rest of their personality. For example, maybe one of your character’s traits is dishonest, but they dislike liars

History:

your character’s past that has key events that influence and shape their beliefs, values, behavior, wants, self-image, etc. Events written down should imply or explain why they are the way they are. For example, if your character is distrustful, maybe they were lied to a lot by their parents when they were a child. Maybe they were in a relationship for twenty years and found out their partner was cheating on them the whole time. If their motive/want is to have positive attention, maybe their parents just didn’t praise them enough and focused too much on the negative

On Mental and Physical Disabilities or Illnesses

if your character experienced a trauma, it needs to have an affect on your character. Maybe they became more angry or impatient or critical of others. Maybe their beliefs on people changed to become “even bullies can be ‘nice’ people: anyone can be a ‘bad’ person”

people are not their illness or disability: it should not be their defining trait. I have health anxiety, but I’m still idealistic, lazy, considerate, impatient and occasionally spiteful; I still want to become an author; I still believe that people are generally good; I still value doing what make me feel comfortable; I still have a positive self-image; I’m still a person. You should fill out your character’s personality at least half-way before you even touch on the possibility of your character having a disability or illness

Generally everything about your character should connect, but hey, even twins that grew up in the same exact household have different personalities; they value different things, have different beliefs. Maybe one of them watched a movie that had a huge impact on them.

Not everything needs to be explained. Someone can be picky or fussy ever since they were little for no reason at all. Someone can be a negative person even if they grew up in a happy home.

I believe this is a thought out layout for making well-rounded OCs, antagonists and protagonists, whether they’re being created for a roleplay or for a book. This layout is also helpful for studying Canon Characters if you’re looking to accurately roleplay as them or write them in fanfiction or whatever.

I’m really excited to post this, so hopefully I didn’t miss anything important…

If you have any questions, feel free to send a message.

- Chick

101K notes

·

View notes