Photo

Ceremonial Attire

Upon reaching the Grand Vizier’s palace, the Admiral was first dressed in brocaded fur, followed by the Chief Secretaries, the religious leader, and the Governor of Istanbul, who were each adorned in large-sleeved sable furs.

Honors and Traditions

Kaymakam Pasha then visited the Hall of Audience, where he received greetings and applause. Following tradition, high officials were adorned in robes of honor (caftans) according to a protocol read by the Minister of Finance Istanbul Fun Tours.

Noble Mandate

A noble mandate was issued to the Grand Vizier’s Palace on the day after the Imperial Accession to announce that the Valide Sultan (Queen Mother) of Sultan Selim III would honor the New Imperial Palace (Topkapi Palace) by visiting from the Ancient Palace in Beyazit on the 15th day of the month. Additionally, it was noted that the Bairam ceremonial parades on the 17th day had been recorded in protocol books.

Tradition of Burials

Most Ottoman Sultans not only ascended the throne but also followed ancient protocol by being buried in tombs. This tradition symbolized the transition from one Sultan’s reign to another, highlighting the cycle of succession and continuity.

Symbolism of the Throne

The golden throne placed before the Gate of Happiness served as a symbol of magnificence for one Sultan’s reign while marking the solemn departure of another Sultan into eternity, all within a span of a few hours.

Sultan Selim III’s Challenges

Sultan Selim III, known for his reformist tendencies and openness to novelty, faced challenges in implementing reforms, particularly in modernizing the army and navigating relationships with Western powers amidst the backdrop of historical traditions and resistance to change.

0 notes

Photo

Events During the Fortification Efforts

Incidents During the Fortification

Throughout the ten days of constructing the earthwork fortifications, several incidents occurred, highlighting the tension and resistance against authority. Initially, when two tax-collectors approached the area, they were met with demands to surrender their weapons. Upon refusal, they were fired upon and killed. These tax-collectors, although not official government officers, represented the despised tax farmer, contributing to the animosity of the villagers due to their exploitative practices.

Subsequent Confrontations

Shortly after the altercation with the tax-collectors, seven more Turks approached the village and were promptly ordered to surrender. They complied, and the group, comprising two zaptiehs, two tax-collectors, one clerk, and two Pomaks (Mohammedan Bulgarians), were held in a Bulgarian house. Despite being detained, they were treated well, except for one zaptieh who was deemed to have committed acts of cruelty and was consequently sentenced to death and executed Bulgaria Tours.

Capture of a Carriage

A few days later, a closed carriage approached the fortifications along the road and was commanded to surrender. Ignoring the demand, the occupants attempted to flee and were met with gunfire. The carriage was seized, revealing two men and three women inside. Tragically, two men and one woman were killed in the exchange of fire. Another woman, in a desperate attempt to defend herself, grabbed a sabre and struck at one of the insurgents, resulting in her death. The surviving woman was captured but treated well until the arrival of Turkish forces, upon which she was released.

Limited Casualties Caused by Insurgents

According to available information, these incidents resulted in the deaths of only two women at the hands of the insurgents. However, one of these deaths was accidental, highlighting the chaotic nature of the confrontations. Contrary to claims by Turkish authorities in Philippopolis, who reported a higher death toll of twelve, concrete evidence supporting these claims is lacking, leading to skepticism from observers like Mr. Schuyler.

The events surrounding the fortification efforts were marked by confrontations and violence, reflecting the simmering tensions between the villagers and representatives of authority. While resistance was evident, casualties were limited, with most incidents arising from clashes during attempts to disarm or apprehend individuals. Skepticism regarding official casualty figures underscores the need for further investigation and verification of claims made by both sides involved in the conflict.

0 notes

Photo

A Daunting Task in Harsh Conditions

Arduous Journey

Mr. Baring and Mr. Schuyler face a formidable challenge in their assigned task. They have embarked on their mission with earnest determination, visiting the towns and villages ravaged by the Bashi-Bazouks. Their objective is to witness firsthand the devastation wrought upon these communities and to listen directly to the accounts of the villagers. This endeavor demands extensive travel, often spanning five to fifteen hours a day, along roads that are scarcely navigable, particularly for carriages. Enduring the scorching sun, exacerbated by the oppressive August humidity, adds to the grueling nature of their journey. Mr. Baring has already fallen ill twice due to the combination of overexertion, rigorous labor, and the relentless heat. Even Mr. Schuyler, accustomed to the rigors of such expeditions from his previous travels through Turkestan, finds the conditions nearly unbearable Guided Turkey Tours .

Emotional Toll

While the physical challenges of their mission are daunting, it is the emotional toll that weighs heaviest upon them. The heart-rending cries of despair echoing through the air, the sight of grieving women and children, and the poignant encounters with homeless and starving individuals evoke profound anguish. Everywhere they turn, they are met with scenes of sorrow—widows and orphans mourning the loss of loved ones, with no shelter or sustenance to comfort them. The relentless repetition of tragic narratives, the exhaustive process of gathering and corroborating evidence, all contribute to the overwhelming burden borne by Mr. Baring and Mr. Schuyler.

Enduring Hardship

Despite the formidable challenges they face, Mr. Baring and Mr. Schuyler press on with their mission, driven by a sense of duty and a commitment to uncovering the truth. Their resilience in the face of adversity is commendable, yet the toll on their physical and emotional well-being is undeniable. The enormity of the suffering they witness, the desperation of those they encounter, leaves an indelible mark on their psyche. It is a task that few would willingly undertake, and one that they may find difficult to revisit in the future. Yet, their perseverance in the pursuit of justice and accountability serves as a testament to their unwavering dedication to their cause.

0 notes

Photo

A Daunting Task in Harsh Conditions

Arduous Journey

Mr. Baring and Mr. Schuyler face a formidable challenge in their assigned task. They have embarked on their mission with earnest determination, visiting the towns and villages ravaged by the Bashi-Bazouks. Their objective is to witness firsthand the devastation wrought upon these communities and to listen directly to the accounts of the villagers. This endeavor demands extensive travel, often spanning five to fifteen hours a day, along roads that are scarcely navigable, particularly for carriages. Enduring the scorching sun, exacerbated by the oppressive August humidity, adds to the grueling nature of their journey. Mr. Baring has already fallen ill twice due to the combination of overexertion, rigorous labor, and the relentless heat. Even Mr. Schuyler, accustomed to the rigors of such expeditions from his previous travels through Turkestan, finds the conditions nearly unbearable Guided Turkey Tours .

Emotional Toll

While the physical challenges of their mission are daunting, it is the emotional toll that weighs heaviest upon them. The heart-rending cries of despair echoing through the air, the sight of grieving women and children, and the poignant encounters with homeless and starving individuals evoke profound anguish. Everywhere they turn, they are met with scenes of sorrow—widows and orphans mourning the loss of loved ones, with no shelter or sustenance to comfort them. The relentless repetition of tragic narratives, the exhaustive process of gathering and corroborating evidence, all contribute to the overwhelming burden borne by Mr. Baring and Mr. Schuyler.

Enduring Hardship

Despite the formidable challenges they face, Mr. Baring and Mr. Schuyler press on with their mission, driven by a sense of duty and a commitment to uncovering the truth. Their resilience in the face of adversity is commendable, yet the toll on their physical and emotional well-being is undeniable. The enormity of the suffering they witness, the desperation of those they encounter, leaves an indelible mark on their psyche. It is a task that few would willingly undertake, and one that they may find difficult to revisit in the future. Yet, their perseverance in the pursuit of justice and accountability serves as a testament to their unwavering dedication to their cause.

0 notes

Photo

Collectivization and Economic Policies

Collectivization and Economic Policies (1950-1958)

Collectivization of Land (1950-1952)

In 1950, Bulgaria adopted the “Model Statute of the Collective Farms” (TKZS), modeled closely on the Soviet kolkhoz statute. The collectivization of land under the First Five Year Plan progressed significantly:

Year Collective Farms Farmers (%) Arable Land (%)

1944 28 — —

1946 480 3.7% 3.5%

1948 1,110 11.2% 6%

1952 2,747 52.3% 60.5%

The forced collectivization peaked in 1950, witnessing a significant increase in the number of collective farms. By the end of the First Five Year Plan, 60% of arable land and 50% of all farms were transformed into cooperatives Guided Istanbul Tour.

Economic and Labor Policies (1950-1957)

In 1950, a new system of compulsory state supplies was introduced, obliging farmers to provide a fixed quantity of grain to the state, irrespective of the yield. The year 1951 saw the implementation of a new Labor Code, issuing job passports and prohibiting job changes. The Second Five Year Plan (1953-1957) continued the focus on industrial expansion, particularly in heavy industry, and intensified land collectivization.

Capital Investments and Industrial Preferences (1953-1957)

A comparison of capital investments between the First and Second Five Year Plans reveals a clear preference for industrial development:

Sector 1st Five Year Plan (Billion Leva) 2nd Five Year Plan (Billion Leva)

Industry 5.9 13.0

Agriculture 1.2 3.2

Transport and Communications 2.1 3.1

Others 2.8 4.7

Total 12.0 24.0

The preferred category of industry can be further divided into heavy and light industry

Year Heavy Industry (%) Light Industry (%)

1939 29% 71%

1948 35% 65%

1952 39.1% 60.9%

1955 45.2% 54.8%

Acceleration of Collectivization (1953-1958)

The tempo of collectivization in agriculture accelerated towards the end of the Second Five Year Plan. It set the stage for the “great leap forward” at the beginning of the Third Plan:

Year Collective Farms (TKZS) Farmers Average Acreage per Farm

1953 2,744 207 2,127 acres

1958 3,290 374 2,850 acres

In 1957, the Labor Code underwent revision. By April 10, 1958, the Socialist sector dominated Bulgaria’s national economy, constituting:

98% of entire industrial production

87% of entire rural-economic production

99% of domestic trade

93% of national income.

0 notes

Photo

Collectivization and Economic Policies

Collectivization and Economic Policies (1950-1958)

Collectivization of Land (1950-1952)

In 1950, Bulgaria adopted the “Model Statute of the Collective Farms” (TKZS), modeled closely on the Soviet kolkhoz statute. The collectivization of land under the First Five Year Plan progressed significantly:

Year Collective Farms Farmers (%) Arable Land (%)

1944 28 — —

1946 480 3.7% 3.5%

1948 1,110 11.2% 6%

1952 2,747 52.3% 60.5%

The forced collectivization peaked in 1950, witnessing a significant increase in the number of collective farms. By the end of the First Five Year Plan, 60% of arable land and 50% of all farms were transformed into cooperatives Guided Istanbul Tour.

Economic and Labor Policies (1950-1957)

In 1950, a new system of compulsory state supplies was introduced, obliging farmers to provide a fixed quantity of grain to the state, irrespective of the yield. The year 1951 saw the implementation of a new Labor Code, issuing job passports and prohibiting job changes. The Second Five Year Plan (1953-1957) continued the focus on industrial expansion, particularly in heavy industry, and intensified land collectivization.

Capital Investments and Industrial Preferences (1953-1957)

A comparison of capital investments between the First and Second Five Year Plans reveals a clear preference for industrial development:

Sector 1st Five Year Plan (Billion Leva) 2nd Five Year Plan (Billion Leva)

Industry 5.9 13.0

Agriculture 1.2 3.2

Transport and Communications 2.1 3.1

Others 2.8 4.7

Total 12.0 24.0

The preferred category of industry can be further divided into heavy and light industry

Year Heavy Industry (%) Light Industry (%)

1939 29% 71%

1948 35% 65%

1952 39.1% 60.9%

1955 45.2% 54.8%

Acceleration of Collectivization (1953-1958)

The tempo of collectivization in agriculture accelerated towards the end of the Second Five Year Plan. It set the stage for the “great leap forward” at the beginning of the Third Plan:

Year Collective Farms (TKZS) Farmers Average Acreage per Farm

1953 2,744 207 2,127 acres

1958 3,290 374 2,850 acres

In 1957, the Labor Code underwent revision. By April 10, 1958, the Socialist sector dominated Bulgaria’s national economy, constituting:

98% of entire industrial production

87% of entire rural-economic production

99% of domestic trade

93% of national income.

0 notes

Photo

Embracing Nature's Challenges Rain or Shine

A Walk in the Rain

Would you walk on muddy mountain paths even if rain-loaded dark clouds hovered above, and a sharp wind rushed through you, releasing cold raindrops into your clothes? For the members of GOLDOSK, a nature sports and hobby club, the answer is a resounding yes. Last Sunday, despite the challenging weather, a group of nature enthusiasts gathered to walk through the mountains and brooks with smiles on their faces.

Soaked to the Skin, Yet Smiling

Sticky mud shackles their progress, and the vision is obscured by the downpour. Soaked to the skin and chilled to the marrow, the group, comprising kids, men, women, and seniors, moves under dark clouds, through rain and a sharp wind. They walk towards Barla, undeterred by the elements, sharing the love of nature in all seasons. The mountains they pass give way, sometimes leading the way.

Finding Beauty in the Chaos

Raindrops gather on the ground, forming tiny murky brooks, creating a symphony of plashing sounds. Yellow and white crocuses smile at them amidst the challenging conditions. Despite the mud, cold, and rain, the group looks at each other and smiles, finding beauty in the chaos. They are not deterred by the mess; instead, they consider the suffering towards the moment of purification from stress and inner dirt Guided Tours Turkey.

Sacred Moments of Learning

“Why endure this misery when you could rest in your cozy houses?” some might ask. Yet, for GOLDOSK, the suffering is sacred, leading to moments of learning and purification. Hakan Ayan, one of GOLDOSK’s founders, explains, “We met with nature, made peace with it. People started their weeks free of trouble or stress.” The experience of being in nature together breaks down invisible walls, bringing people together in ways they wouldn’t have expected.

From Two Friends to an Association

GOLDOSK’s journey began with two friends discussing how to enjoy their weekends. Small walking activities grew, and from five members, they became ten, then a hundred. Today, GOLDOSK is a thriving association where people from all walks of life come together. Besides nature trips, the organization has formed groups focused on music, skiing, painting, and photography, embracing diverse interests within the community.

0 notes

Photo

Embracing Nature's Challenges Rain or Shine

A Walk in the Rain

Would you walk on muddy mountain paths even if rain-loaded dark clouds hovered above, and a sharp wind rushed through you, releasing cold raindrops into your clothes? For the members of GOLDOSK, a nature sports and hobby club, the answer is a resounding yes. Last Sunday, despite the challenging weather, a group of nature enthusiasts gathered to walk through the mountains and brooks with smiles on their faces.

Soaked to the Skin, Yet Smiling

Sticky mud shackles their progress, and the vision is obscured by the downpour. Soaked to the skin and chilled to the marrow, the group, comprising kids, men, women, and seniors, moves under dark clouds, through rain and a sharp wind. They walk towards Barla, undeterred by the elements, sharing the love of nature in all seasons. The mountains they pass give way, sometimes leading the way.

Finding Beauty in the Chaos

Raindrops gather on the ground, forming tiny murky brooks, creating a symphony of plashing sounds. Yellow and white crocuses smile at them amidst the challenging conditions. Despite the mud, cold, and rain, the group looks at each other and smiles, finding beauty in the chaos. They are not deterred by the mess; instead, they consider the suffering towards the moment of purification from stress and inner dirt Guided Tours Turkey.

Sacred Moments of Learning

“Why endure this misery when you could rest in your cozy houses?” some might ask. Yet, for GOLDOSK, the suffering is sacred, leading to moments of learning and purification. Hakan Ayan, one of GOLDOSK’s founders, explains, “We met with nature, made peace with it. People started their weeks free of trouble or stress.” The experience of being in nature together breaks down invisible walls, bringing people together in ways they wouldn’t have expected.

From Two Friends to an Association

GOLDOSK’s journey began with two friends discussing how to enjoy their weekends. Small walking activities grew, and from five members, they became ten, then a hundred. Today, GOLDOSK is a thriving association where people from all walks of life come together. Besides nature trips, the organization has formed groups focused on music, skiing, painting, and photography, embracing diverse interests within the community.

0 notes

Photo

Klissura's Unfulfilled Hopes

The Lingering Shadows of Klissura’s Despair

This article delves into the aftermath of Klissura’s devastation, shedding light on the broken promises and insurmountable barriers that continue to plague the survivors. Despite assurances of restitution, the plight of Klissura epitomizes the bureaucratic hurdles and unfulfilled hopes that define the post-atrocity landscape.

The Elusive Return of Cattle and Retorts

In the wake of Klissura’s destruction, promises echoed through the air like a distant, fleeting melody. The Mutle-Serif of Philippopolis tantalized the victims with visions of assembled cattle awaiting identification, only to be revealed as an illusion. The pledged return of retorts and cattle remained an unfulfilled promise, leaving the survivors in Klissura grappling with shattered expectations Tour Bulgaria.

The Philippopolis Passport Paradox

The seemingly straightforward directive to reclaim lost cattle at Philippopolis unfolded into a Kafkaesque paradox. While the prospect appeared just and equitable, Mr. Schuyler unraveled the hidden layers of deception. Striking at the core of Turkish duplicity, he uncovered the issuance of strict orders preventing villagers from leaving without a special passport. The freedom to claim one’s cattle now danced behind bureaucratic barriers—a cruel twist in the quest for justice.

Imprisoned Amidst Ruins

In Klissura, where hope was already a scarce commodity, the people faced an additional blow. Stripped of their homes and livelihoods, they found themselves imprisoned amidst the ruins. The promise of identifying and reclaiming their cattle in Philippopolis turned into a cruel irony as the survivors were forbidden to leave the remnants of their village, perpetuating their state of despair.

A Glimpse into Systemic Deception

The restrictive passport measures exemplify the broader Turkish strategy in responding to demands for justice and reform. A veneer of compliance conceals a maze of bureaucratic obstructions, rendering promises hollow. Klissura’s ordeal serves as a poignant illustration of the systemic deception employed to feign adherence to international demands while perpetuating the suffering of the afflicted.

Klissura’s Cry for Genuine Restoration

Klissura’s cry echoes beyond its razed landscape—a plea for genuine restoration, devoid of empty promises and bureaucratic machinations. The international community must heed the lessons of Klissura, exposing the façade of compliance and demanding tangible actions to rebuild shattered lives. Only through unyielding pressure can Klissura’s survivors hope for a future unmarred by broken promises and bureaucratic barriers.

0 notes

Photo

Klissura's Unfulfilled Hopes

The Lingering Shadows of Klissura’s Despair

This article delves into the aftermath of Klissura’s devastation, shedding light on the broken promises and insurmountable barriers that continue to plague the survivors. Despite assurances of restitution, the plight of Klissura epitomizes the bureaucratic hurdles and unfulfilled hopes that define the post-atrocity landscape.

The Elusive Return of Cattle and Retorts

In the wake of Klissura’s destruction, promises echoed through the air like a distant, fleeting melody. The Mutle-Serif of Philippopolis tantalized the victims with visions of assembled cattle awaiting identification, only to be revealed as an illusion. The pledged return of retorts and cattle remained an unfulfilled promise, leaving the survivors in Klissura grappling with shattered expectations Tour Bulgaria.

The Philippopolis Passport Paradox

The seemingly straightforward directive to reclaim lost cattle at Philippopolis unfolded into a Kafkaesque paradox. While the prospect appeared just and equitable, Mr. Schuyler unraveled the hidden layers of deception. Striking at the core of Turkish duplicity, he uncovered the issuance of strict orders preventing villagers from leaving without a special passport. The freedom to claim one’s cattle now danced behind bureaucratic barriers—a cruel twist in the quest for justice.

Imprisoned Amidst Ruins

In Klissura, where hope was already a scarce commodity, the people faced an additional blow. Stripped of their homes and livelihoods, they found themselves imprisoned amidst the ruins. The promise of identifying and reclaiming their cattle in Philippopolis turned into a cruel irony as the survivors were forbidden to leave the remnants of their village, perpetuating their state of despair.

A Glimpse into Systemic Deception

The restrictive passport measures exemplify the broader Turkish strategy in responding to demands for justice and reform. A veneer of compliance conceals a maze of bureaucratic obstructions, rendering promises hollow. Klissura’s ordeal serves as a poignant illustration of the systemic deception employed to feign adherence to international demands while perpetuating the suffering of the afflicted.

Klissura’s Cry for Genuine Restoration

Klissura’s cry echoes beyond its razed landscape—a plea for genuine restoration, devoid of empty promises and bureaucratic machinations. The international community must heed the lessons of Klissura, exposing the façade of compliance and demanding tangible actions to rebuild shattered lives. Only through unyielding pressure can Klissura’s survivors hope for a future unmarred by broken promises and bureaucratic barriers.

0 notes

Photo

Klissura's Unfulfilled Hopes

The Lingering Shadows of Klissura’s Despair

This article delves into the aftermath of Klissura’s devastation, shedding light on the broken promises and insurmountable barriers that continue to plague the survivors. Despite assurances of restitution, the plight of Klissura epitomizes the bureaucratic hurdles and unfulfilled hopes that define the post-atrocity landscape.

The Elusive Return of Cattle and Retorts

In the wake of Klissura’s destruction, promises echoed through the air like a distant, fleeting melody. The Mutle-Serif of Philippopolis tantalized the victims with visions of assembled cattle awaiting identification, only to be revealed as an illusion. The pledged return of retorts and cattle remained an unfulfilled promise, leaving the survivors in Klissura grappling with shattered expectations Tour Bulgaria.

The Philippopolis Passport Paradox

The seemingly straightforward directive to reclaim lost cattle at Philippopolis unfolded into a Kafkaesque paradox. While the prospect appeared just and equitable, Mr. Schuyler unraveled the hidden layers of deception. Striking at the core of Turkish duplicity, he uncovered the issuance of strict orders preventing villagers from leaving without a special passport. The freedom to claim one’s cattle now danced behind bureaucratic barriers—a cruel twist in the quest for justice.

Imprisoned Amidst Ruins

In Klissura, where hope was already a scarce commodity, the people faced an additional blow. Stripped of their homes and livelihoods, they found themselves imprisoned amidst the ruins. The promise of identifying and reclaiming their cattle in Philippopolis turned into a cruel irony as the survivors were forbidden to leave the remnants of their village, perpetuating their state of despair.

A Glimpse into Systemic Deception

The restrictive passport measures exemplify the broader Turkish strategy in responding to demands for justice and reform. A veneer of compliance conceals a maze of bureaucratic obstructions, rendering promises hollow. Klissura’s ordeal serves as a poignant illustration of the systemic deception employed to feign adherence to international demands while perpetuating the suffering of the afflicted.

Klissura’s Cry for Genuine Restoration

Klissura’s cry echoes beyond its razed landscape—a plea for genuine restoration, devoid of empty promises and bureaucratic machinations. The international community must heed the lessons of Klissura, exposing the façade of compliance and demanding tangible actions to rebuild shattered lives. Only through unyielding pressure can Klissura’s survivors hope for a future unmarred by broken promises and bureaucratic barriers.

0 notes

Photo

Klissura's Unfulfilled Hopes

The Lingering Shadows of Klissura’s Despair

This article delves into the aftermath of Klissura’s devastation, shedding light on the broken promises and insurmountable barriers that continue to plague the survivors. Despite assurances of restitution, the plight of Klissura epitomizes the bureaucratic hurdles and unfulfilled hopes that define the post-atrocity landscape.

The Elusive Return of Cattle and Retorts

In the wake of Klissura’s destruction, promises echoed through the air like a distant, fleeting melody. The Mutle-Serif of Philippopolis tantalized the victims with visions of assembled cattle awaiting identification, only to be revealed as an illusion. The pledged return of retorts and cattle remained an unfulfilled promise, leaving the survivors in Klissura grappling with shattered expectations Tour Bulgaria.

The Philippopolis Passport Paradox

The seemingly straightforward directive to reclaim lost cattle at Philippopolis unfolded into a Kafkaesque paradox. While the prospect appeared just and equitable, Mr. Schuyler unraveled the hidden layers of deception. Striking at the core of Turkish duplicity, he uncovered the issuance of strict orders preventing villagers from leaving without a special passport. The freedom to claim one’s cattle now danced behind bureaucratic barriers—a cruel twist in the quest for justice.

Imprisoned Amidst Ruins

In Klissura, where hope was already a scarce commodity, the people faced an additional blow. Stripped of their homes and livelihoods, they found themselves imprisoned amidst the ruins. The promise of identifying and reclaiming their cattle in Philippopolis turned into a cruel irony as the survivors were forbidden to leave the remnants of their village, perpetuating their state of despair.

A Glimpse into Systemic Deception

The restrictive passport measures exemplify the broader Turkish strategy in responding to demands for justice and reform. A veneer of compliance conceals a maze of bureaucratic obstructions, rendering promises hollow. Klissura’s ordeal serves as a poignant illustration of the systemic deception employed to feign adherence to international demands while perpetuating the suffering of the afflicted.

Klissura’s Cry for Genuine Restoration

Klissura’s cry echoes beyond its razed landscape—a plea for genuine restoration, devoid of empty promises and bureaucratic machinations. The international community must heed the lessons of Klissura, exposing the façade of compliance and demanding tangible actions to rebuild shattered lives. Only through unyielding pressure can Klissura’s survivors hope for a future unmarred by broken promises and bureaucratic barriers.

0 notes

Photo

Unraveling the Threads of Rebellion

Avrat-Alan’s Fragile Resistance

Whispers of Dissent Avrat-Alan’s Reluctant Rebellion

In the annals of rebellion, Avrat-Alan emerges as a complex tableau where the echo of dissent met the stark reality of pragmatism. Unlike Otluk-kui, the resistance in Avrat-Alan lacked the fervor and unity that typifies a formidable uprising. Instead, it unfolded as a hesitant and fragmented endeavor, revealing a stark divide between the impulsive actions of the youth and the measured reservations of their elders.

The elder and more prudent segment of Avrat-Alan’s populace abstained from participating in the uprising, demonstrating a sagacious reluctance to engage in a futile endeavor. Their counsel fell on deaf ears as the impetuousness of the young men propelled them into a venture that their elders viewed with skepticism. This schism in generational perspectives delineates a community grappling with the cost-benefit analysis of rebellion—an internal struggle laid bare by the ensuing events Bulgaria Holidays.

The Unraveling Bubble Avrat-Alan’s Resistance in Retreat

As Hafiz Pacha’s forces approached Otluk-kui, a pivotal moment unfolded in Avrat-Alan—one that exposed the vulnerability of a rebellion built on shaky foundations. A substantial portion of the insurgents ventured out to reconnoiter, leaving the rest of the populace torn between fear of Turkish retribution and the hope of appeasement. In a surprising turn of events, the pragmatic majority, disenchanted with the ill-fated rebellion, rose against their youthful compatriots.

The insurgents who remained within Avrat-Alan found themselves confined, not by the might of Turkish forces but by the hands of their own disillusioned community. A desperate attempt to signal appeasement to Hafiz Pacha unfolded as the elders, recognizing the futility of resistance, sought to distance themselves from the impulsive actions of the rebels. The confinement of the insurgents within the konak, and the subsequent message to Hafiz Pacha, was a clear indication of the majority’s disapproval and their desire to disentangle themselves from a rebellion that held no promise.

The collapse of the rebellion, when confronted by the advancing Turkish troops, resembled the bursting of a fragile bubble. The uprising, built on the misjudgments of the youth and lacking the foundational support of the wider community, crumbled under the weight of its own impracticality. Avrat-Alan, in this moment, became a microcosm of the larger narrative—a cautionary tale of rebellion without collective conviction, where the fleeting aspirations of the young met the sobering reality dictated by the elders’ pragmatism.

0 notes

Photo

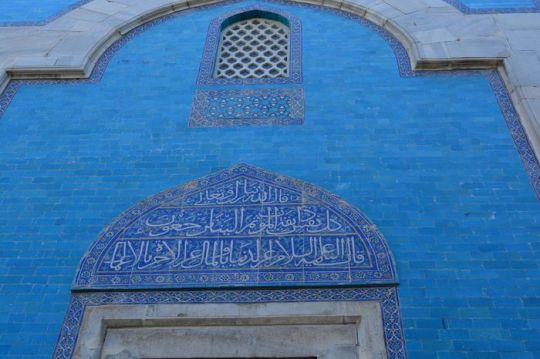

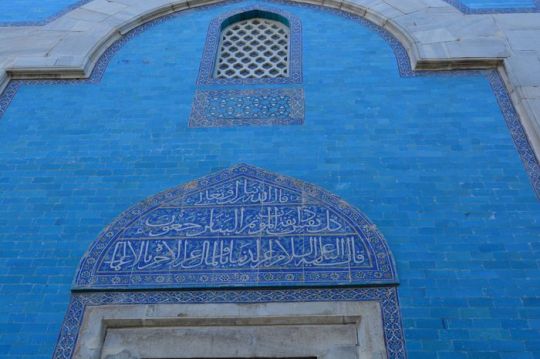

The Greek inscription

The dome is 57 feet in diameter, and rests on eight piers, intersected by a double row of thirty-four green and white columns, sixteen of which are in the lower row, and the remaining eighteen in the galleries. The Greek inscription, running round the frieze, is ornamented with carved vine leaves and grapes, and is a dedicatory poem to the two saints; but all the mosaics and frescoes forming part of the original ornamentation of the church have been covered with whitewash. Ducange states that this was the church in which the papal Nuncio, for the time being, was allowed to hold divine service in Latin ; and it was here that Pope Virgil sought refuge from the wrath of Justinian for having excommunicated Patriarch Menas; this was also the church which the Emperor attended in state every Easter Tuesday.

Mehmed Pasha Mosque, on the south-west side of the Hippodrome, not far from Kutchuk Ayiah Sofia. Admission 5 piastres (10d.). This mosque is regarded (Dr. A. G-. Paspati, ‘ BvavnvaX MeXerat ) as the ancient church of St. Anastasia Pharma- kolytria, variously attributed to Anastasius Dicorus, in the fifth century, and to Gregory Nazianzenus, the latter of whom preached orthodoxy in it during the predominance of Arianism in the city. The church has been rebuilt and restored several times, and notably by Basil of Macedon, who replaced its wooden cupola by a stone one.

Most of the ornaments and relics were carried off by the Latins during the crusade of 1204. The immediate vicinity of this church, extending as far as the Cistern of Philoxenus (Thousand and One Columns), is supposed by Dr. Paspati to have been the site of the city Praetorium and the Portico of Domninus. The church was converted into a mosque in 1571 by Mehmed Pasha Socoll, son-in-law of Selim II. The tiles with which the interior is ornamented guided tours istanbul, and especially those forming the panels over the windows and the canopy over the pulpit, are masterpieces of Persian art. The courtyard is one of the most picturesque, and makes a charming subject for sketches or photographs.

The Church in the Fields

The Church in the Fields (17 Movrj TT)? Xwpa?), now Kahriyeh Jamesi, better known to travellers as the Mosaic Mosque. Admission 5 piastres per head. The Imam (priest) in charge is not always in attendance, but lives close by, and will always come if sent for. This mosque suffered so severely during the earthquakes of 1894 as to be in danger of falling down, and it has been deemed advisable, in consequence, to close it for an indefinite period. It is situated near the land walls and close to Edimth Kaj)u (Adrianople Gate); it is one of the most interesting of all the whilom Byzantine churches, both on account of its plan and of the mosaic pictures covering the walls of its outer and inner nartheces, the greater part illustrating the life of Christ. Its Greek name, showing that it originally stood outside the city, carries the foundation back to the period prior to 413 A.D., when it was enclosed within the walls of Theodosius.

Very probably the church was erected as a private chapel in connection with the Hebdomon Palace. Justinian restored it and added a basilica, and in the early part of the seventh century it was further restored and embellished by Crispus, son-in-law of the Emperor Phocas, who was imprisoned in it for treachery by Heraclius, and subsequently became a monk. In the early part of the twelfth century the church was rebuilt and restored by Maria Ducaina, mother-in-law of Alexius Comnenus; and about the middle of the fourteenth century its chapels and nartheces were again restored throughout and embellished by the patrician Theodoras Metochites.

0 notes

Photo

TWO THEODOSIAN CAPITALS

7. TWO THEODOSIAN CAPITALS

Workshop on the Island of Prokonnesos in the Sea of Marmara (?) 5th – 6th century Marble

H. 39,5 cm; diam. 34,5 cm

The village of Maryan, Elena area, Lovech region

8. CAPITAL WITH HUMAN FACES

Eocal workshop 6th century Sandstone

H. 33 / 34 cm; diam. of the base 20 cm; abacus 34 x 35 cm

Discovered accidentally in the fields of the village of Belopoptsi, Sofia region

9. CAPITAL WITH HEADS OF RABBITS

Workshop on the Island of Prokonnesos in the Sea of Marmara 5th century Marble

H. 40 cm; diam. 35 cm; abacus 41 x 41 cm

The capital entered the Museum in 1914 brought from the town of Obzor, Burgas region

10. CAPITAL WITH TWO CORNUCOPIAE

Local workshop Late 5th – early 6th century Limestone H. 30 cm; diam. 39 cm; abacus 44 x 64 cm

Discovered in a Medieval church in the village of Lyutibrod bulgaria tour, Vratsa region, together with 13 more Ionian Kaempfer capitals from the same date, now in the Museum of Vratsa.

11. BALCONY SLAB OF A PULPIT

Local work, Constantinople type 6th century Grey sandstone 1,36 x 1,42 x 0,23 m

Discovered in Sofia, at the corner of Saborna and Kaloyan streets, during construction works. Prob-ably the pulpit belonged to a church dedicated to St. George. The slab was found together with some fragments of the pulpit railings decorated with embossed crosses.

12. SLABS AND COLUMNS FROM ALTAR SCREENS A reconstruction

A PAIR OF SLABS

Workshops on the Island of Prokonnesos in the Sea of Marmara 5th – 6th century

Marble

1,15 x 0,93 x 0,14 m; 1,17 x 0,96 x 0,12 m

Discovered during archaeological research of a ba-silica in Hisar, Plovdiv region, next to the southern side entrance

A PAIR OF COLUMNS

Workshops on the Island of Prokonnesos in the Sea of Marmara 6th century Marble

H. 1,10; 0,25 X 0,23; h. 0,99; 0,21 x 0,21

Discovered in the fortress ofTsepina, the village of Dorkovo, Plovdiv region

13. RELIQUARY

Eastern Mediterranean 4th century Alabaster H. 12 cm; diam, of the body 7,4 cm; diam. of the opening 4 cm

Discovered in the altar area of an Early Christian basilica in Odessos (Varna) during archaeological research Varna, Regional Museum of History, lnv. Nil 1130

The reliquary is shaped as a flask.

14. RELIQUARY COMPLETE WITH TWO BOXES

Asia Minor (Syria)

5th century

Discovered in Dzhanavara, by the southern bank of the Varna Lake, 4 km southwest of Varna. A find of 1920 in the area of a church from the Early Christian age. It was in the altar, in a niche in the eastern wall of a small crypt built in bricks. The reliquary and the boxes were found undamaged in the church. The reliquary was in a fabric sack, the inner box was wrapped in dark cloth. The reliquary contained fragments of human bones and a piece of wood probably the Golgotha Cross, which turned into ashes the minute they were uncovered and the air was let inside. The same church treasured other relics of saints found near the pulpit.

0 notes

Photo

University Centre

Varna is the second largest University Centre in the country and also has a Naval School, opened in 1881 when the Russian fleet was transferred to Varna.

Notable monuments are: Museum of History and Art in the former girls’ high school built in the last century. The museum was opened to mark the 13th centenary of the Bulgarian State, founded in 681. The museum has 40 exhibition halls, three of which show artefacts from the famous Varna Necropolis. Also on display are other ancient finds, and artefacts from the Middle Ages and the National Revival period. There is an art gallery exhibiting modern Bulgarian art.

District History Museum, 7 Osmi Noemvri Street, tel. 2-24-23: Archaeological Museum, 5 Sheinovo Street, tel. 2-30-62; Ethnographic Museum, 22 Panagyurishte Street, tel. 2-00-80; Museum of the Working-Class Revolutionary Movement, 3 Osmi Noemvri Street; Museum-Park Wladyslaw Warnenczik;Navy Museum‘ 2 Chervenoarmeiski Blvd. tel.

2-24-06; The Art Gallery, 65 Lenin Blvd, tel. 2-42-81; Georgi Velchev Museum, 8 Zhechka Karamfilova Street, tel. 2-56-39; Natural Science Museum in the Maritime Gardens, tel. 2-82-94; Aquarium and Museum, 4 Chervenoarmeiska Street, tel. 2-41-93 turkey sightseeing.

The Roman Thermae, built in the 2nd century.

The Roman Bath from the 3rd-4th century.

St Nicholas Church 1866

The Cathedral of the Holy Virgin, erected in the centre of Varna in 1886. The iconostasis and the bishop’s throne are the work of master-woodcarvers from Debur, while the icons were painted by a group of Russian painters.

I he Pantheon Memorial in the Maritime Gardens.

The National Revival Alley in the Maritime Gardens, with busts of outstanding figures of that period.

Dimiter Blagoev Monument in the boulevard of the same name, s’

Karel Skorpil Monument, founder of Bulgarian archaeology.

The Monument to Bulgarian-Soviet Friendship, near the Yuri Gagarin stadium.

Hotels: Cherno More, three stars, 35 Georg) Dimitrov Blvd. tel. 3-40-88; Odessa, 1 Georgi Dimitrov Blvd, three stars, with 170 beds, restaurant, bar, coffee shop, information desk, rent-a-car service. Tel. 2-53-12; Moussala, 3 Moussala Street, tel. 2-26-02; Orbita, 25 V.Kolarov Street, tel. 2-51-62; Preslav, 1 Avram Gachev Street, tel, 2-25-83; Repoublika, September Ninth Square, tel. 2-83-53.

Tourist Information Bureau, 6 Koloni Street, tel. 2-28-03.

Balkantourist Bureau, 3 Moussala Street, tel. 2-55-24 and 2-08-07.

Balkan Airlines Office, 2 Shipka Street, tel. 2-29-48.

The Union of Bulgarian Motorists, 9 Dr Zamenhov Street, tel. 2-62-93.

The Rila International Bureau, 3 Shipka Street, tel 2-62-73.

In the Dianavaraster section are the foundations of a basilica from the 6th century with some marble columns, capitals and cornices and a receptacle containing mortal remains, decorated with precious stones, standing between two reliquaries of silver and marble.

0 notes

Photo

Gorna Oryahovitsa

Some ten kilometres to the left a road leads to Gorna Oryahovitsa (pop. 39,000) — the largest railway junction of North Bulgaria. It was a craft and trade centre during Ottoman rule. After the Liberation it developed as a railway station following the construction of the Varna-Sofia line. Hotels: Raho- vets, two stars, 5 floors, 3 suites and 146 beds, restaurant, night club, national tavern, cafe (tel. 4-16-30).

Return to E-85 and enter the picturesque Derventa Gorge, where, facing each other on the rocks, are the Tiansfiguration Monastery and the Holy Trinity Monastery.

The Transfiguration Monastery is 6 km north of Veliko lumovo. The ruins of the old mediaeval monastery are some half a kilometre in the woods, south of the present-day monastery. It was probably founded during the reign of Ivan Shishrnan, in the 1570s. It fell into oblivion for several centuries, after repeated plundering. The frescoes were painted by Zahari Zograph of the Samokov school of painting. He painted the whole church and icons from 1849 to 1851. Interesting from an ethnographic point of view is the Doomsday fresco painted on the eastern side of the vestibule. Also remarkable is the Wheel of Life fresco on the outside southern altar wall, showing human life from a philosophical point of view.

In 1838 the Tryavna master-engravers made a magnificent iconostasis which is one of the masterpieces of the Tryavna school of wood-carving. They also made the iconostasis in the small Anunciation Church. The large monastery library holds valuable incunabula, historical documents, etc.

The Holy Trinity Monastery is situated among rocks op posite the Transfiguration Monastery, on the steep banks of the River Yantra. It is supposed to have been founded by Patriarch Euthimius. Several prominent literary figures worked there.

Veliko Turnovo

Veliko Turnovo (pop. 63,500; is one of Bulgaria’s most beautiful towns. It was capital of the Second Bulgarian State from 1187 to 1396. There was a Byzantine fortress on the Tsarevets hill in the 5th-6th century, built by Justinian, which was captured by the Slavs in the 7th century sofia sightseeing. In 1185 Turnovo was the centre of a nationwide uprising led by the brothers Assen and Peter. The uprising was successful^eter was declared Tsar and Tumovo capital of the new Bulgarian state, which lasted for two centuries until Bulgaria fell under Ottoman domination. The town maintained lively commercial links with Dubrovnik, Genoa and Venice. It became one of the largest literary centres of its time. Magnificent works were written here, some of which are still presented — Manasses9 Chronicle (in the Vatican library) and Tsar Ivan Alexander’s Tetraevan- gelia (in British Museum, London). In 1350 Theodosius of l umovo founded Kilifarevo Monastery near Turnovo which was a literary school.

Students from all over the country, from Russia, Wallachia and Serbia, studied here; Patriarch Euthimius was among them. He founded a second literary school in the Holy Trinity Monastery, known as the Turnovo School. His disciples, Grigorii Tsamblak and Konstantin Kostenechki, continued their teachings in Wallachia, Serbia and Russia. On July 17, 1393, after a three-month siege, 1 urnovgrad fell under Ottoman domination. The capital was burnt, destroyed and plundered, but the spirit of people remained alive and many uprisings broke out in the 16th, l7th and 18th centuries. In the 19th century the town was a major craft centre. A Bulgarian men’s school was opened followed by a girl’s school in 1845. In 1835 the town was the centre of an uprising, known as the Velcho conspiracy. In 1870 Vassil Levski founded the Turno- vo revolutionary committee. During the Uprising of April 1876 Tumovo was the centre of the First Revolutionary District. Troops led by General I.V.Gurko liberated the town on June 25, 1877.

0 notes