Text

What is the value of digital storytelling? [Week 13/Conclusion]

This is my last reflection, and it is the only one I’m writing at the same time I’m posting it. As a turn away from the typical weird/wonderful/worrying set-up that I’ve used in most of my previous reflections, since it is my final reflection I figured I’d do something a bit more self-indulgent. In the presentation I made for this course on digital storytelling as meaning of life philosophy, I introduced the class to the concept of web weaving and as the experiment for that class, we each made a small web weave to convey some meaning of life value.

I think web-weaves are an extremely poignant form of digital storytelling, and that it is an interesting form to consider presenting digital humanities through. The emphasis on a specific theme or concept in the assemblage of images, quotes, and occasionally sounds seems to echo the emphasis of the theme or area of interest with which digital humanists engage. So, on that note, my final reflection will actually be a separate post from this one, where I’ve assembled different quotes and images that reflect my understanding of the value of (digital) storytelling, through a form of digital storytelling that I’m particularly fond of, found here.

0 notes

Text

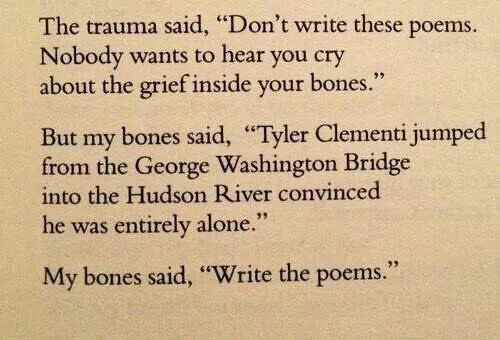

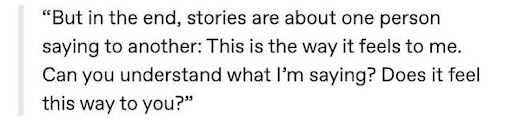

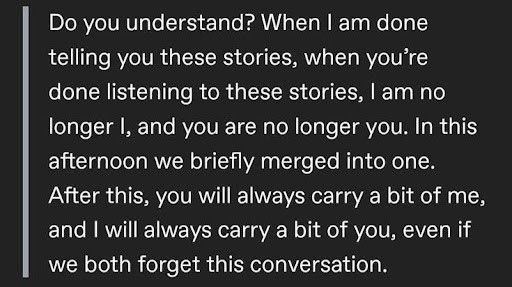

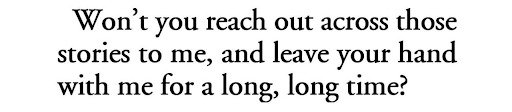

on the value of storytelling;

Into the Water - Paula Hawkins // The Nutritionist - Andrea Gibson // LIFE Magazine 1963 - James Baldwin // Anti-depressants are so not a big deal - Crazy Ex-Girlfriend // Nobel Prize Acceptance Speech 2017 - Kazuo Ishiguro // Invisible Planets - Hao Jingfang (tr. Ken Liu) // tumblr user @/poseidonsarmoury // Road to Hell (Reprise) - Hadestown // Letters to Milena - Franz Kafka // The Catcher in the Rye - J.D. Salinger // Exandria Unlimited: Calamity - Brennan Lee Mulligan

181 notes

·

View notes

Text

How can we understand documentaries in the digital context? [Week 12/Alternative Media in Documentary Studies]

Writing from:

December 2023

A presentation from a classmate about how the digital problematizes our concept of what a documentary is, with emphasis on alternate media forms within digital space

Class discussion on machinima

Weird: Digital space has led film institutes to (financially) support forms of documentary which might not typically be called film - such as a documentary portrayed as a website for buying shoes which relays the storyteller’s experience of queerness and presentation through the pairs of shoes they wore growing up. In this way, the expansiveness of the digital isn’t just self contained but encourages our understanding of other concepts like ‘documentary’ or ‘film’ to likewise become more expansive.

Wonderful: Digital forms of documentary like machinima seem to offer a way for individuals who might not otherwise have the opportunity to create documentaries due to the cost of equipment and similar concerns to do so at a much lower budget.

Worrying: Whether, despite the accessibility (both financial and physical), documentary forms like machinima might lead us away from the communal practices that filmmaking tends to ensure and towards a much more alienated and isolated version of documentation.

0 notes

Text

Does digital creativity aid us in language learning? [Week 11/Digital Language Learning]

Writing from:

November 2023

A Presentation on Digital Language Learning from a classmate, with emphasis on creative ways of learning language in digital space

A course forum on which this post was originally made. No changes were made as even with the context of the presentation, much of my thoughts here remained just as relevant and reflective of my thoughts on digital language learning.

When discussing my own identity, I typically refer to myself as 'monolingual', but that said I spent almost all of my elementary and secondary education taking some form of French courses. I've also done (online) beginner courses for German quite a few times but never to an extent that I would call truly successful for my aims.

At the end of high school I would say I was probably as close to bilingual as I've yet achieved, I've never been great at speaking French, but I could write in prose in French and could read things like children's books, menus, directions, or transcripts fairly well, I could also understand what was being said to me most of the time even if I couldn't respond very well. It's been around five years since then and I can still usually understand French in both spoken and written forms, but my ability to respond even in writing is not as strong anymore. In the five years that my French has gone relatively unpracticed, I've had months/years where I've tried to keep it refreshed using tools like Duolingo and other free access learning tools, but I've found that the things that Duolingo successfully 'teaches' are the same things that don't fade as easily. The benefit of learning French in school was that I had teachers whose entire classroom was covered in posters/instructions/signs that were also in French, everyone was required to speak in French - even if it was wrong or ill-pronounced - and any tools like laptops/ipads/textbooks were set up so that they were also in French (so, for an iPad or laptop, the system settings would be changed to French so even things like app names were immersive). This made it much easier to try and actually work out solutions like how I wanted to say things by actually thinking in French, rather than just doing translations in my head. But things like Duolingo seem to be much more proficient at teaching translation than they are actually teaching a language - which isn't a detriment, translation is a helpful skill to have in numerous contexts.

In attempts with German, or even attempts at refreshing with French, I've tried to mix some of these 'immersive' things that previous teachers of mine used with my daily life since while I live a life that is very much English immersive, finding small things that made me encounter German or French more frequently were a little beneficial. However, without a setting where I could actually practice either language as the language and not as a different way to say English phrases, I typically found myself getting left at a very basic skill level that I wouldn't even call understanding as much as I would call it recognition.

1 note

·

View note

Text

How can digital storytelling give us insight to meaning of life values? [Week 10/Digital Storytelling & the Meaning of Life]

Writing From:

November 2023

A presentation I gave to the class about using digital storytelling as meaning of life philosophy

This week I presented how (and why) I think we might be able to use digital storytelling as a philosophical way to understand contemporary meaning of life ideas. For posterity’s sake or something, I thought something different (and maybe interesting) for my blog post this week would be to post the first draft of presentation notes I made without editing them. For context, my process for presentation notes tends to be a three-step process where the first step is idea-word vomit where I just write whichever ideas pop into my head around the presentation, the second step is more oriented word vomit where I start to tie the ideas together and give them a more academic voice, and the third step is where I make the cleanest version where there’s clearer transitions between ideas and language that supports the academic context in which I’m presenting. These notes are from the end of the first step, as I was just starting to transition into the second step of that process:

So a few kind of contextualizing things for this presentation

This is about digital storytelling. As we’ve returned to in nearly every class thus far, the separation of ‘digital’ forms of humanities from more historical or ‘traditional’ forms of humanities turns out to be a significantly false dichotomy. For that reason, storytelling will be featured in this presentation and discussions of ‘typical’ storytelling through the digital sphere will also be present.

As this presentation is concerned with the meaning of life, some of my presentation will be addressing why finding meaning of life is so urgent an issue for philosophers and the average person alike. Please take this as a trigger warning for references to suicide. While it is in the context of finding reasons to continue to live and there will be no detailed references or descriptions, suicide is something that will come up.

Why do I care about this?

Academically: the idea of academic ‘canons’ frustrates me and I think that while the digital realm does not escape many of the issues of accessibility as we’ve discussed throughout this course, I do think that the creativity of storytelling and the (compared to typical academia) accessibility of the digital makes digital storytelling an especially worthwhile place to find a broadening of what we call academic sources.

Personally: I’m someone who very tangibly has found different meaning of life values through my engagement with digital stories and many of the friends I have can also point to a digital story as providing some element of their outlook on what it means to live well. I’ve spent most of my life struggling with depression and suicidality and it is through digital storytelling - both encountered and created - that I have found ideas about what it means to live a meaningful life.

So, what is the meaning of life?

I’m starting off bold, I’ll tell you exactly what the meaning of life is right now. I’m joking, but I will preface by being transparent to the sort of framework I’m coming at this from.

Kindness & Curiosity

(or, as me and my friends like to refer to it, Brainheartism)

These are things that I take to be guiding points in my own life, but this is not an endorsement. These have helped me, but I don’t think the meaning of life is any sort of one size fits all equation

(near end, minor point to bring up how digital storytelling isn’t just a power for “good” and empowering meaning of life ideas. Digital storytelling has just as much potential to enforce the idea that we are powerless, we will never find true happiness, etc.)

What is DH (in the context of presentation)?

If humanities tends to be defined as a collection of academic fields concerned with what it means to be human on largely social/cultural/political bases, primarily as it relates to the sharing of ideas, then I can think of very little that is as pertinent to the humanities as storytelling is.

I mean, if you’ve taken any history course the truth of that is evident. But it’s clear in every facet of the humanities. Storytelling and stories are something extremely human. And storytelling is one of the main ways that humans at large share experiences, feelings, and ideas with one another.

In ‘on the origin of stories’ Brian Boyd writes that “We come preequippped to attend to, relate to, take our lead from, and understand other humans.” (132) and that “Trying to understand why others do what they do matters [...] in both human life and literature.” (141) both in the context of explaining why we as humans find so much worth in the venture of storytelling.

So, if I’m defining digital humanities, or even just trying to focus on one aspect of it, I’m led to stories and their storytellers. Like the conversations we’ve had as a group about the notions of digital humanities vs. just humanities, storytelling has gained its own digital counterpart, similar to digital humanities, i remain uncertain whether the term digital storytelling actually conveys anything that simply storytelling does, but for the sake of this presentation and the context of this course, I’ll be using it.

How is DH relevant to philosophy?

In general, storytelling (whether fictional or not) has great persuasive power over the construction of our ethical values, we see that in the construction of children’s books and entertainment with ‘morals’, in the continued legacies of ideals that get passed on through the anecdotes that parents tell their kids, and that governments tell their people. Some of the most basic and foundational works that philosophy turns to even now come from the dramatic retellings contained in Greek storytelling. Socrates is held as the founder of Western philosophy, is one of the first people we consider a moral philosopher, and everything we know about him we know through stories about him, dialogues echoing him.

To be clear, I don’t think this is at all problematic. As much as philosophy wishes to be about achieving an absolute truth, I personally hold it to be more about striving towards it despite an acceptance that there isn’t actually any single truth that can be meaningfully reached. It is perfectly acceptable to me - and, apparently most of the history of academic philosophy - to see the story of Socrates and find it meaningful, to derive value and construct ideas about the meaning of life held by Socrates and his students as well as ponder how those ideas influence my own ideas about meaning of life. Socrates need not even be an actual person for this to remain sufficient and a worthwhile source, let alone a person being conveyed 100% truthfully.

I doubt many contemporary thinkers would necessarily disagree with this either. But the perhaps hypocritical nature of the oh-so-rational philosophical academia emerges when you try to step out of the canon. Particularly if you try to step out of the canon towards ‘non-philosophers’.

Philosophy is storytelling. Especially when it comes to ethics. To define what is good or bad, all we do is forge and pass on stories of what we think it means to do good or do bad. To that end, we make stories about what it means to live well. Not solely in the sense of literature or theatre or the arts or fictional works, even in casual storytelling.

But for the sake of this, we’ll focus on the way that meaning of life values can be created with, conveyed through, and crafted by digital storytelling.

0 notes

Text

Can we be genuine in a digital space defined by memes? [Week 9/Memes, Music, and Meaning]

Writing from:

November 2023

Presentation from a classmate about the role of memes in the digital world, particularly in music

Follow-up discussion with the class about memes and the ability to be genuine alongside/with them

Vox's "Why Do Memes Matter?" (2019)

This week might be the most incoherent thoughts I have had about a topic yet, specifically in terms of trying to separate it into weird/worrying/wonderful. Because of that, this will probably be the most word vomit-y that these posts get (hopefully), so apologies for that!

As someone who could be referred to as a 'digital native' in the sense that I grew up in a time where digital access is much more accessible than previous (though I was later accessing it than most others my age), memes have always been something I've encountered while existing in digital spaces. Additionally, I'm someone who is inclined towards the meaningfulness of silly and playful things. A quote from Brennan Lee Mulligan, "Profundity and absurdity are deeply in love, they go hand-in-hand, right? The world is profoundly meaningful and deeply silly," aptly echoes the sentiment I have towards silliness. Due to both of these aspects of who I am, I'm inclined to be fairly defensive of memes, at least in their theoretical sense, as something that can be entirely meaningful and which does not negate our ability to be genuine.

However, also because of my existence as someone in digital spaces, I have been witness to countless uses/contents of memes that leave me extremely frustrated. A fairly recent example is the use of terms like 'girl math' or 'girl dinner' which (to my knowledge) came about from reference to things like using cash instead of debit so the money doesn't count and to the 'meals' comprised of minuscule portions that girls tend to eat, respectively. These have developed into a trend that is very openly the repetition of misogynistic ideals, except it is often used by the same people (particularly women) who can be found calling themselves feminists. The problem I see here isn't the hypocrisy (though, on a personal level I do find that highly irritating) but how the silliness of memed phrases like 'girl dinner' and 'girl math' can hide the maliciousness of the ideology that encourages our engagement with those terms. When 'girl math' has come to mean 'simple' or 'incorrect' math, the implicit association of girlhood with a lack of intelligence rings loudly for anyone willing to interrogate what the genuine suggestion under the layer of silliness has to offer.

So, to that end, I do think it is true that memes don't harm our ability to be genuine, but I do think they can obfuscate what we are genuinely saying - both to ourselves and to those around us. That is, if I am using a meme, I am always doing it in a genuine manner, I am always portraying something about how I perceive the world. Certainly, it is in a silly or playful format, but the use of playfulness as an excuse for thoughtlessness is a practice that memes typically lead to.

0 notes

Text

How does 'universality' influence our approach to accessibility? [Week 8/Digital Accessibility]

Writing from:

November 2023

Presentation by a classmate about digital accessibility and a follow-up group discussion of the topic.

Much of this text is copied from a discussion post I made on the same topic in the course forum.

George H. Williams’ “Disability, Universal Design, and the Digital Humanities.” (2012)

I really enjoyed (was intrigued by? Found interesting? One of those words, not sure that ‘enjoyed’ is the best to use) this reading. In particular, I found it highlighted that ‘accessibility’ is something that doesn’t need to be (and perhaps shouldn’t be) addressed as a concern of people with disabilities. In all fields, but maybe most evident in the realm of the digital, accessibility can concern a lot more than just the physical or mental ability of the user. One example in the reading was how Williams pointed out that making sure that a website is accessible through a mobile device doesn’t just make it more widespread, it also specifically becomes a benefit to “African Americans, Hispanics, and individuals from lower-income households” who are more likely to get their online access through those devices.

I agree with the running thread in the reading that universal design is, of course, universal and thus something beneficial to everyone, not just individuals with disabilities. However, I am perhaps a little dissatisfied with the necessity of universality as a reason to do something that can help people with disabilities. This is not a problem I have with the reading itself, but rather the context of the reading and largely the notions of ‘good’ and ‘value’ that our society holds as absolute. Specifically, it would be preferable if someone could lay out why universal design would benefit people with disabilities and that would be enough for people to think it a useful and good endeavour to use universal design. However, instead what tends to need to be done is an argument that cites the benefits of universal design towards potential legality issues/government grants, aesthetic (in the sense of consumable and monetizable) value, and efficiency.

Weird: While I am very much cognizant of the value of things like universal design, I wonder if universal design ends up being a way to ignore situations in which particular design is necessary. There are very few situations where I can imagine universal design is actually going to be able to fully account for universal differences in ability, and I wonder if something more like flexible design where there is a multiplicity in the forms that things can take might be worth orienting our accessible practices towards. This would likely mean giving up efficiency as a rationale for universal design, which would have both costs and benefits.

Wonderful: An increased turn towards universal design seems to indicate an increased willingness to consider those beyond society’s determined norms in various sectors, both in digital accessibility and in material accessibility in things like architecture. I’ve had jobs where part of the training was ensuring that we understood universal (instructional) design to be able to relay information to students. This seems like a good step.

Worrying: Whether the basis of things like ‘efficiency’ as an argument for the value of universal design and accessible practice risks worsening the degree to which people with disabilities are seen as non-valuable.

0 notes

Text

How does the idea of 'aura' help us understand digital objects? [Week 6/Art, Architecture, and Design]

Writing from:

October 2023

A presentation from a classmate about design, art, and architecture in digital contexts, with emphasis on the concept of aura

An online presentation by Béatrice Joyeux-Prunel and Leora Auslander, “Do we need Digital Visual Studies?” (2023), hosted by Geneva University.

Walter Benjamin’s “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction.” (1935) Translated by Harry Zohn.

Weird: Is the aura of an object linked inextricably to its material presence? That is, I’m left wondering after class discussion whether there is something lost that cannot be regained when we ‘transfer’ physical objects to the digital world. Certainly, an object encountered in the digital world has a different aura than it would in its original material form, but I don’t know whether I’m convinced that this means the aura is less.

Wonderful: I think understanding aura in a way that challenges the idea that the presentation of digital objects is inherently lesser in an experiential way than their material counterparts can lead us to an attitude that is more inclined towards accessibility. Using museums as an example, if they think that they can create digital exhibits that have the same sort of aural quality that an in-person exhibit would, then that means that people who are not able to access the actual museum might still be able to access the experience and knowledge it provides.

Worrying: That said, I do still think that there are things about the digital that still (at this point in time, at least) limit how we understand objects as opposed to how we understand them in the material world. In the presentation she gave, Auslander brought up an experience she had as a historian looking at the bras that people in concentration camps during the Holocaust made and how essential the ability to feel with her hands how small the bodies which wore those bras were to comprehend the state those people were in while they were making clothing for themselves. Even a scaled 3D recreation of the garment fails to provide the experience of holding the object. I find myself worried that a turn towards digital accessibility will also be a turn away from material accessibility on the part of institutions like museums which tend towards preservation, where if a researcher can access information online then they are less likely to be permitted to access the tangible experience of being with the object in material space. This seems to indicate an increased distance from the subjects (and objects) of study, especially in humanities, that risks limiting our inclination towards empathy, care, and understanding in conveying the research that we embark on.

0 notes

Text

How can Digital Humanities make our assumptions about the world explicit? [Week 4/Simulations]

Writing from:

October 2023

A presentation from a classmate about simulations in digital humanities, featuring the Oregon Trail

An article by Shawn Graham, “Behaviour Space: Simulating Roman Social Life and Civil Violence.” (2009)

A presentation from Deborah Poff, “Misconduct and Publication Ethics: From Ordinary Forms of Discrimination to the Ethically Opaque World of AI.” (2023)

Weird: A reference to Joshua Epstein that Graham uses in his article I thought was one particularly relevant to my own interests and concerns with the digital, as Graham writes, “Epstein argues [...] the principal strength of agent-based modelling [is that] it requires modellers to make explicit their assumptions about how the world operates.” n a recent colloquium hosted by the philosophy department, the speaker, Deborah Poff, raised concerns about ChatGPT in the context of academic publishing and editing. Of particular concern for her was the inability of ChatGPT and similar technology to satisfy the requirements of ‘authorship’ even when it might very well be the writer of an essay or book. The definition that Poff used to contextualize what authorship meant insisted on the ability of someone to maintain responsibility for the work they are producing, both in the sense of being praised and being blamed for ideas that might be contained within. While someone can certainly say that ChatGPT is responsible for an essay that contains bias or some form of social injustice, it is harder to claim that ChatGPT itself holds itself responsible for what it produces.

Wonderful: Perhaps not wonderful this week in the positive sense but wonderful in the curious sense, during Poff’s presentation, though I understand the seeming urgency of ChatGPT as a problem for academic publishing, most of my thoughts were oriented towards the reality that ChatGPT introduces very few new issues to academic publishing. There are still ghostwriters and publishing mills made specifically for people to take the writing of others and make it their own. But I think the idea of Epstein’s, that ABM forces modellers to make their assumptions explicit, speaks to the main issue at hand with many of the complaints I have seen about any technological advancement that threatens change to the way academia works. Namely, the issue of responsibility for the biases that writing contains. Though countless authors claim responsibility for their ideas but do nothing to confront the biases or injustices their writing represents, there is still an ability to locate their sources and parse out the development of ideas that reflect implicit assumptions they may have made. With something like ChatGPT, its nature as a black box means that though we might take issue with the result it produces, it can be much harder to find the implicit assumptions it makes or target where those assumptions emerge from.

I think this speaks to the power of things like ABM and the necessity of digital humanities to try and focus on tools that require the creator or user to interact with them in ways that necessitate that they make their assumptions explicit, both to encourage the individual to confront what may be their own biases, as well as make clear to other people who encounter their work what considerations they perhaps ought to make given what they know about the assumptions that have been made.

Worrying: Despite the ability of the digital to allow us to make our implicit assumptions more explicit in the case of ABMs, I do still worry about the way that many people tend to treat digital products and mechanisms as ones free of bias and thus more reliable than human work. This is not at all to say that technology is in some way inferior, only that it is always inextricably linked to the humans who use, create, and challenge it - inclusive of the biases and assumptions those humans have. To view the digital/technology as more objective than humans seems to lead to (and has certainly led) to a lack of responsibility for or even an examination of how different digital tools and technology reify existing biases, particularly ones that confirm existing social injustice.

0 notes

Text

Is digital 'life' liberatory or just escapism? [Week 3/Metaverse]

Writing from:

September 2023

Having watched the machinima documentary ‘Second Bodies’

Class discussion about metaverse as liberatory as well as the role that capitalist interest plays in the forms that concepts like the metaverse take.

Weird: The tendency that people have in referring to life in the digital space in forms like Second Life as other lives, and not as an extension of one’s real life. This speaks a bit to what I’ll emphasize in my worry at the end of this post, but it seems that there is a layer of separation that the digital allows people to draw between the actions they take and roles they play in ‘real’ life versus the ones they engage in within these ‘digital’ lives that they understand to be separate.

Wonderful: The cathartic (and perhaps emancipatory) power that these sorts of digital lives can offer is extremely cool, particularly in view of people who are forced to interact with the material world differently because of our world’s marginalizing practices. While the digital sphere certainly does not get rid of or lack these practices, there are ways that we can shift (and sometimes escape) the weight marginalization places on us through the transformation of our identities in the digital sphere that we cannot always achieve in physical space.

Worrying: A concern I find myself returning to (and, for the version of myself now posting this, a concern that recurred throughout the course and one that still remains for me) is the question if what we do in digital versions of our lives - whether metaverse-esque whole lives like Second Life or just things like social media - is just a way of turning away from or rendering ourselves ignorant of not just the problems in our lives, but also the solutions to them. While I absolutely see, and have felt, the benefit of digital space as emancipatory, I often wonder how I might have rendered my material world more emancipatory if I did not have the sort of quasi-escape from it that the digital can offer.

0 notes

Text

How does technology enforce injustice? [Week 2/Coding]

Writing from:

September 2023

A class discussion about code and how who can (and do) code is not simply a ‘skill issue’.

An article by Audrey Watters, “Men (Still) Explain Technology to Me: Gender and Education Technology.” (2015)

The majority of this is taken from a post that I created for the class’s discussion forum

In reading Audrey Watters' article regarding the injustice and inequality present in even the ways that ideas are explained in the field of technology (especially education technology), I found her thoughts quite compelling and certainly relevant to any discussion of gender disparities in the digital space. However, the two main things that stuck out to me were the scope of her discussion as well as some of the concepts she presented.

Regarding the scope, evidently, her focus is how gender remains a point of inequality in education technology, specifically in ways that undermine and invalidate the knowledge that women have and in ways that often lead to harassment and other forms of harm. This is an extremely important topic and there are moments when Watters seems to reach beyond this scope to poke at other social dynamics that intersect with gender in ways that are extremely relevant to the issue of online harassment that targets women with accusations of ineptitude. In general, it is not an issue that Watters does this, in fact in most cases I would say it is better to try and elaborate on how intersecting social inequalities change the dynamics of things like the gender divide, but Watters tends to elaborate on these issues only in bits that seem akin to placing buzzwords in an article. I am not claiming anything towards Watters' intent, I can see the good intention in her words but as a reader, I came away with a feeling of inconsistency regarding her ideas and how much a commitment to those ideas was not necessarily present in how she wrote the paper.

One occurrence of this is that at one point Watters brings up the restrictions that software claiming to offer 'personalization' actually places on an individual, a specific example that she uses is: "Gender, for example, is often a drop-down menu where one can choose either "male" or "female". This is certainly a correct observation and I would find no problem with this sentence or any questioning of Watters commitments if not for a sentence quite early in her article where she claims, "Just over half of all games are men (52%); that means just under half are women." The critique Watters is raising in talking about the restrictions of personalization seems to be one she is willing to undermine to support the claim she is making. In discussing the percentage of men, her point on how it seems incorrect to call anyone to suggest video games should reflect the actual demographics 'social justice warriors' is still salient if she commits to the fact that the remaining 48% might include genders beyond just women. In a similar vein, Watters critiques Isaacson's book by pointing out that his writing makes it seem that "the history of computing is the history of men, white men." This is an important distinction to be sure, but it is also one that Watters herself does not elaborate on beyond alluding to the fact that there might possibly be an issue of race at play. Any other references Watters makes to race - whether rhetorical questions or specific data about percentages of employment for certain races in the technological sector - remain very surface level in an article that otherwise cares to elaborate greatly on the dynamics at play for women in (education) technology.

Doing some self-reflection, my reaction to this reading is absolutely contextualized by my own issue with the role that 'mansplaining' has come to have in the cultural zeitgeist. While it certainly does point out issues with reality, even the word 'mansplain' suggests that the people who participate in these explanations and lessons that assume the inferiority of those they explain to due to social injustice and inequality are always men. This is far from the case. To me, the real issue that both Solnit and Watters speak to in their writing is about how assuming that the knowledge of others is insufficient due to some social/political/cultural difference in identity leads to the reification of those social injustices. However, in tying the idea that what is happening here might be called mansplaining or might be encapsulated by the phrase "men (still) explain technology to me" at worst fails to grasp the reality and depth of the issue and at best encourages a white feminist stance on what it means to support social equality. Watters' article brings up surface-level references to the role of race in the technological field but which only really engages with what it means to be a (implicitly white) woman who encounters (implicitly white) men.

All of that said, I'll return to what I found really valuable about Watters’ article. In her discussion of how the presentation and performance of one's identity tends to actually be restricted by the templates of online spaces, Watters brings up the work of Amber Case and the idea of the 'templated self'. Watters' (and Case's) concern is of course education technology and digital spaces, but the questions she raises: "Who is building the template? Who is engineering the template? Who is there to demand the template be cracked open? What will the template look like if we’ve chased women and people of color out of programming?" Are ones that seemingly have the same concerns that emerge in places like critical theory. All that is changing is the specific space/place - "Who is building the template?" seems to have the same basis as what occurs when we question who determines laws, the rules of an institute, etc. This is not to say that Case and Watters' ideas are unsatisfactory or unimportant - specificity creates essential clarity in discussing issues like those of formatted identity - but it does seem to urge a return to the question whether digital humanities is a novel discipline. For me, I wasn't especially convinced that digital humanities has something inherently different in its make up that separates it from humanities at the start of this course. This article, both in the ideas that I found compelling and the habits that I found a bit dissatisfying, seems to persuade me further that if there is a difference to be drawn between 'digital humanities' and 'humanities' it is a fairly arbitrary one.

In summary:

Weird: analyses of the problems in the coding communities (and digital humanities as well) that do not commit fully to intersectional analysis seem to overlook the reificatory processes in which our society – especially that as intertwined with capitalism as technology is – is ingrained.

Wonderful: awareness/keeping transparent our recognition of how technological fields can be restrictive helps us to actually combat the habits which further ingrain those unjust habits.

Worrying: the fact that the very structure of the field of technology/methods for understanding seems to pose an intrinsic barrier which will always be exclusionary in unjust and unequal ways.

0 notes

Text

What is Digital Humanities? [Week 1/Introduction]

Writing from:

September 2023

The first week of my MA program (Philosophy, specialization in Digital Humanities)

A particular interest in digital storytelling and the role it plays in our understanding of life's meaning

As an introduction post, it is worthwhile to clarify what the purpose of this is: to fulfill a requirement for a course I have to take for the completion of my degree. That said, I also aim for this to be a resource for myself (and potentially others who might stumble across it) to reflect and recall the way my understanding of Digital Humanities and the issues contained within it has changed, developed, and become more complicated as my familiarity with the discipline and my interaction with others within it increases.

This - like all of the other blog posts for this course - is being posted at the end of my term. As someone who tends to be more tactile than technical, which is perhaps a not ideal tendency for someone interested in Digital Humanities. Nonetheless, that tendency led me to write these reflections in a physical journal and the business of school and the several jobs I have to pay for it led to me putting off actually typing up these posts. But, here we are! Several of my other courses have ended, and I am writing between work hours.

The first week of this course, called 'Issues in Digital Humanities' introduced us to Digital Humanities as a whole as well as to a specific question to help centre the course (and one that I carry with me beyond this single course): What is Digital Humanities?

Through discussion and referral to other sources and ideas of individuals beyond those in the class, it became very clear that even a technical definition of the discipline is hard to achieve in a way that seems faithful to Digital Humanities' aims and methods (which are in themselves hard to define or even determine). This was especially evident in a website that the instructor introduced us to, aptly called What Is Digital Humanities? This site generates responses to that question provided by participants in 'Day of DH' events (a date dedicated to examining the state of digital humanities as relayed by those who do work within the discipline) from 2009 to 2014. These responses range from paragraphs to short sentences, illuminating the expansiveness of just DH's definition, without saying anything about the expansiveness of DH itself. One answer I appreciated that came up in the random generation that I did when encountering the site was one from Daniel Hooper: "The stuff humanities people do when they get a computer."

In the syllabus for the course I am writing this post for, we are encouraged to specifically engage with what we find weird, wonderful, and worrying in each post. In future reflections, I imagine it might be easiest to split the post into three sections, each dedicated to one of these 'W's, but this week I think this central question 'What is Digital Humanities?' is all three in a way that would be diminished by my dividing it into three sections. So, instead, I think I'll highlight one main takeaway I have from this question which is weird, wonderful, and worrying: Digital Humanities seems to be relatively boundless. This is weird, especially from the context of Academia from which I write, as even the shape it takes as a quasi-department in which students can specialize is made up entirely of cross-appointed faculty. DH doesn't (and perhaps can't) stand on its own, which is something I think is wonderful and aptly counters the siloing which occurs in discussions of academic disciplines or expertise, if DH is based on its relation to other topics, whether humanities or technology, then it is interdisciplinary in a way that cannot be ignored like other disciplines might. My worry from this is perhaps much more pragmatic than it is theory/conceptually based, but the problem of legitimacy is one that DH faces off against in a multitude of ways. In DH's tendency to admit its own interdisciplinary expansiveness, I wonder if it risks delegitimizing itself. This is not something I think is inherently concerning, but I do think it is concerning in the context of academia, where things like individual grants and departmental funding pay great mind to the legitimacy of what is being funded, and that funding is essential to the survival of research and disciplines in academic spaces.

3 notes

·

View notes